Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia is a serious, chronic, and often debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder. Its causes are still poorly understood. Besides genetic and non-genetic (environmental) factors are thought to be important as the cause of the structural and functional deficits that characterize schizophrenia. This study aimed to compare Toxoplasma gondii infection between schizophrenia patients and non-schizophrenia individuals as control group.

Methods

A case-control study was designed in Tehran, Iran during 2009-2010. Sixty-two patients with schizophrenia and 62 non-schizophrenia volunteers were selected. To ascertain a possible relationship between T. gondii infection and schizophrenia, anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibodies were detected by indirect-ELISA. Data were statistically analyzed by chi- square at a confidence level of 99%.

Results

The sero-positivity rate among patients with schizophrenia (67.7%) was significantly higher than control group (37.1) (P <0. 01).

Conclusion

A significant correlation between Toxoplasma infection and schizophrenia might be expected.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Toxoplasma gondii, ELISA, Iran

Introduction

A bout 30-60% of the population in both developed and developing countries are infected with the parasitic protozoon Toxoplasma gondii. Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan that is widespread globally. Its final hosts are felids, but its intermediate hosts are almost all the warm-blooded animals (1).

Humans become infected in 3 ways: 1- ingesting T. gondii tissue cysts (containing bradyzoites) presented in the undercooked meat (especially lamb and pork) of infected food animals; 2- ingesting highly infectious oocysts (containing sporozoites) presented in water, garden soil, children's sandboxes, etc, contaminated by infected cat feces; 3- congenital trans-placental transmission of rapidly replicating tachyzoites from mothers who become infected during pregnancy (2). It can exist chronically in tissues and organs such as the brain of an immunocompetent host in the form of cysts. The host does not show any physical symptoms or signs in such latent infections (3).

Bedsides host's behavior and psychomotor skills, T. gondi might change the personality as well (1, 3–7).

Torrey et al. (8) found that cat ownership before age 13 was a risk factor for the later development of psychoses and speculated that the transmission of some zoonotic agent such as T. gondii between pets and human beings may be a possible mechanism for schizophrenia. Brown et al. (9) suggested that maternal toxoplasmosis increased the risk of adult schizophrenia in the offspring.

Schizophrenic patients infected with Toxoplasma encompass more levels of antibodies than the same group of non-schizophrenic group (10–12). Moreover, level of IgG, IgM, or IgA antibodies to T. gondii, is higher in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (13–15). Some medications that had been used for treatment of schizophrenia could inhibit the replication of T. gondii in cell culture (16).

There are some risk factors for developing the disorder in later of life including winter or spring birth, urban birth, and prenatal and postnatal infections (17). Hence, environmental studies have rekindled interest in the possible role of infectious agents in schizophrenia (18).

To explore further the association between Toxoplasma infection and schizophrenia, this study was established to compare the amount of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibodies between patients with schizophrenia and non- schizophrenia control group by ELISA.

Materials and Methods

This case-control study was carried out during 2009 and 2010 in Tehran, Iran. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Participants

Sixty-two patients with schizophrenia were recruited from Roozbeh University Hospital, Tehran, Iran. The diagnosis was made by academic psychiatrists according to DSM-IV-TR classification. To evaluate the positive and negative symptoms the PANSS (positive and negative symptoms scale) was used. All patients had no family history of schizophrenia, no history of head trauma and brain surgery. Blood samples were obtained from the patients and control groups in the morning.

Control group consisted of 62 healthy volunteers. They were evaluated to rule out any medical and psychiatric disorders. The patient and control groups were matched as possible on socioeconomic status; dietary habits (especially with regard to eating or drinking uncooked/undercooked meat, milk, or eggs); and age (average of 37.54± 9.75 year in schizophrenic patients and 37.24 ± 10.24 year in healthy volunteers). The factors of urban or rural areas were considered as well. There were no significant differences between two groups with respect to these factors (P>0.05). Duration of illness in schizophrenia patients was from 2 to 37 years.

Based on clinical features the schizophrenic patients were divided to three forms including paranoid, undifferentiated, and disorganized types.

Serological Technique

Serum was separated from whole blood shortly after collection, and stored at−20°C. Tachyzoites of T. gondii, RH strain were collected from peritoneal cavity of mice infected 3 days earlier. The organisms were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 20 min, washed three times in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) pH 7.2, and disrupted by sonication. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 12000g for 1 hour at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and used as the soluble T. gondii antigen. Protein determination was performed using the Bradford method (19).

To establish the ELISA method the 96 well microtitre plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 5µg/ml of soluble T. gondii antigen in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Plates were incubated at 4°C for 24 hours and washed three times with PBST (PBS+20% tween 20) blocked with skimmed milk 1% (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in PBST and washed three times. Sera were diluted serially from 1:10 up to 1:6400 (1:10, 1:100, 1:200, 1:400, 1:800, 1:1600, 1:3200 & 1:6400) and added to each antigen wells in duplicate runs. Positive and negative samples were used in each experiment to confirm the accuracy of the method. Control samples were the sera collected previously tested and confirmed by IFA and ELISA methods. After incubating and washing, anti human IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme (Dako, Produktionsvej, Denmark) diluted 1:1000 in PBST was added; then orthophenylen diamidin (OPD) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to each well as substrate. The reaction was stopped by adding the sulfuric acid (2N) and the optical density was read by an automated ELISA reader (BioTek, USA) at 490 nm (20).

Statistical Analysis

The cut-off was determined as the mean plus two times the standard deviation (M±2SD) of the optical density obtained for negative samples. Then the optical density for schizophrenia patients and non-schizophrenia individuals were compared with the cut-off, separately. All data were analyzed by chisquare at a confidence level of 95% and 99% by SPSS version 13.5.

Results

In this study, 62 cases with schizophrenia and 62 control individuals were compared for anti- Toxoplasma antibody by ELISA. The difference of anti T. gondii antibodies between schizophrenia patients (42 out of 62) and control group (23 out of 62) were statistically significant (P<0.01) (Table1). According to the ELISA test, the mean of optical density in sera from schizophrenia group was higher (0.58) in comparison with control group (0.22) (Table1).

Table 1.

Distribution of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies by ELISA in schizophrenic and non-schizophrenic individuals

| Group | No. | Gender | Age (year) (M±SD) | Mean of OD | ELISA+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female> | No. | % | ||||

| Schizophrenia patient | 62 | 39 | 23 | 37.54±9.75 | 0.58 | 42 | 67.7 |

| Control group | 62 | 26 | 36 | 37.24±10.24 | 0.22 | 23 | 37.1 |

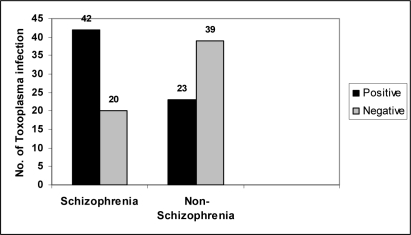

The sero-positivity rate for anti- T. gondii IgG antibodies in patients compared with control group (Fig.1) showed possible relationship between Toxoplasma infection and schizophrenia.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of anti- T. gondii antibodies between schizophrenic patients and non-schizophrenia as control group

There was no significant difference between patients and control groups when socioeconomic status, dietary habits, and age were compared.

The schizophrenia patients were consisted of 16 paranoid, 45 undifferentiated and 1 disorganized types. Although the number of different types of disease was small, there was no statistically difference between type of schizophrenia and anti- T. gondii antibodies.

Discussion

In the present study, the sero- prevalence of anti- T. gondii antibodies was higher in patients with schizophrenia in comparison with control group.

In recent years, serological studies on patients with schizophrenia have been carried out showing that anti- T. gondii antibodies were higher in patients than control groups (14, 15). In this study, patients with schizophrenia had significantly elevated levels of IgG antibodies to T. gondii compared with controls (P <0. 01). This is in accordance with recent studies, which have suggested that infectious diseases could play a role in developing schizophrenia (14, 15).

In humans, proliferating tachyzoites have been detected in glial cells in patients who had developed toxoplasmic encephalitis (2, 21). In another presentation of toxoplasmic encephalitis, T. gondii bradyzoites were observed in Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (2, 22). T. gondii cysts have also been reported in astrocytes in humans (2, 23).

Postmortem investigations of brains from individuals who had schizophrenia have reported many glial abnormalities (18, 24), including decreased numbers of astrocytes (18, 25). Neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine might be affected by tox-oplasmosis, whom are affected in schizophrenic people as well (18, 26).

The role of antibodies in psychotic patients infected with Toxoplasma was shown for the first time in 1953 (27). Torrey et al. reported antibodies in 495 (52%) of 961 psychiatric inpatients compared with 170 (25%) of 681 controls.

The prevalence of antibodies to T. gondii was higher in individuals with schizophrenia than in control groups and the infection with Toxoplasma may confer a risk for schizophrenia (28).

Yazar et al. (18) compared 100 schizophrenic patients with two control groups. In their study, 66% of schizophrenic patients and 23% of controls were positive for IgG titers. Leweke et al. (15) in Germany compared 113 schizophrenic patients with 102 normal people and reported antibodies in 34% of cases compared with 16% of controls.

Saraei et al. compared 104 Iranian schizophrenic patients with 114 normal people and reported T. gondii antibodies in 55.3% of cases and 50.9% in control group (29). It is postulated that patients’ brain plays the most important role in the perception of the relation between toxoplasmosis and schizophrenia disease (3, 30, 31).

In the present study, the seropositivity rate for anti-Toxoplasma antibodies in patient group (67.7%) indicates that chronic Toxoplasma infection is greater compared to control group (37.1%) (P<0.01).

In conclusion, a significant correlation between Toxoplasma infection and schizophrenia might be expected.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Vice Chancellors for Education of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors wish to thank Miss Salimi from Serology Lab for her laboratory assistance educational affairs. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dubey JP. 2010. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans; p. 313. Second edition. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y. Effect of Toxoplasma gondii Infection on the Brain. Schizopher Bull. 2007;33:745–51. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang HL, Wang GH, LiQ Y, Shu C, Jiang MS, Guo Y. Prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in first-episode sch-izophrenia and comparison between Toxoplasma seropositive and Toxopla-sma seronegative schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006:40–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegr J, Zitkova S, Kodym P, Frynta D. Induction of changes in human behavior by the parasitic protozoan Toxoplasma gondii . Parasitol. 1996;113:49–54. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegr J, Kodym P, Tolarova V. Correlation of duration of latent Toxoplasma gondii infection with personality changes in women. Biol Psychol. 2000;53:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holliman RE. Toxoplasmosis, behavior, and personality. J Infect. 1997;35:105–10. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)91380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havlicek J, Gasova Z, Smith AP, Zvara K, Flegr J. Decrease of psychomotor performance in subjects with latent asymptomatic tox-oplasmosis. Parasitol. 2001;122:515–20. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001007624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Could schizophrenia be a viral zoonosis transmitted from house cat? Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:167–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown AS, Schaefer CA, Quesenberry CP, Liu L, Babulas VP, Susser ES. Maternal exposure to toxoplasmosis and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:767–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torrey EF, Rawlings R, Yolken RH. The antecedents of psychoses: a case–control study of selected risk factors. Schizophr Res. 2000;46:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado GG, Garcia LJ. Reactivity of the intradermal test with toxoplasmosis in schizophrenic patients. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 1979;31:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li QY, Luo XN, Li L, Tong F. Comparative study on Toxoplasma infection in patients with schizophrenia and affective disorder. Med J Wuhan Univ (Chinese) 1999;20:222–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu H, Yolken RH, Phillips M, et al. Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in recent-onset schizophrenia (abstract) Schizophr Res. 2001;49:53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yolken RH, Bachmann S, Rouslanova I, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in ind-ividuals with first-episode schizophrenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:842–44. doi: 10.1086/319221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, et al. Antibodies to infectious agents in individuals with recent onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:4–8. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones-Brando L, Torrey EF, Yolken R. Drugs used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder inhibit the replication of Toxoplasma gondii . Schizophr Res. 2003;62(3):237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii and Schizophrenia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1375–80. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cetinkaya Z, Yazar S, Gecici O, Namli MN. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in patients with schizophrenia—preliminary fin-dings in a Turkish sample. Schizophr Bull. 2007 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm021. Advance Access April 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnstone A, Thorpe R. Immunochem-istry in practice. 3rd ed. London: Blackwell Science; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JD, Holliman RE. Toxoplasm-osis. In: Gillespie SH, Hawkey PM, editors. Medical Parasitology practical approach. 1st ed. New york: Oxford university press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell HC, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Lorenzo AM, Lampert PW, Gajdusek DC. Toxoplasmosis of the central nervous system in the adult. Electron microscopic observations. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1978;41:211–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00690438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertoli F, Espino M, Arosemena JR, Fishback JL, Frenkel JK. A spectrum in the pathology of toxoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:214–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghatak NR, Zimmerman HM. Fine structure of Toxoplasma in the human brain. Arch Pathol. 1973;95:276–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotter DR, Pariante CM, Everall IP. Glial cell abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders: the evidence and implications. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:585–95. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doyle C, Deakin JFW. Fewer astrocytes in frontal cortex in schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder [abstract] Schizophr Res. 2002;53:106. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sims TS, Hay J. Host-parasite relationship between congenital Toxoplasma infection and mouse brain: role of small vessels. Parasitology. 1995;110:123–7. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000063873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torrey EF, Bartko jj, Lun ZR, Yolken RH. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:729–36. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torrey EF. Are we overestimating the genetic contribution to schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:159–170. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraei-Sahnesaraei M, Shamloo F, Jahani Hashemi H, Khabbaz F, Alizadeh SA. Relation Between Toxoplasma gondii Infections and Schizophrenia. Iranian J Psychaitr Clin Psychol. 2009;15(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boks MPM, Liddle PF, Burgerhof JGM, Knegtering R, Van den Bosch R-J. Neurological soft signs discriminating mood disorders from first episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill K, Mann L, Laws KR, Stephenson CME, Nimmo-Smith I, McKenna PJ. Hypofrontality in schizophrenia: a metaanalysis of functional imaging studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:243–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]