Abstract

General catalytic asymmetric routes toward cyclopentanoid and cycloheptanoid core structures embedded in numerous natural products have been developed. The central stereoselective transformation in our divergent strategies is the enantioselective decarboxylative alkylation of seven-membered β-ketoesters to form α-quaternary vinylogous esters. Recognition of the unusual reactivity of β-hydroxyketones resulting from the addition of hydride or organometallic reagents enabled divergent access to γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes through a ring contraction pathway or γ-quaternary cycloheptenones through a carbonyl transposition pathway. Synthetic applications of these compounds were explored through the preparation of mono-, bi-, and tricyclic derivatives that can serve as valuable intermediates for the total synthesis of complex natural products. This work complements our previous work with cyclohexanoid systems.

1. Introduction

The stereoselective total synthesis of polycyclic natural products depends greatly on the available tools for the efficient preparation of small and medium sized rings in enantioenriched form.i Facile means to elaborate these monocyclic intermediates to fused, bridged, and spirocyclic architectures within multiple ring systems would significantly contribute to modern synthetic methods. While many strategies have been developed for the preparation of six-membered rings and their corresponding polycyclic derivatives, approaches toward the synthesis of five- and seven-membered rings would benefit from further development.

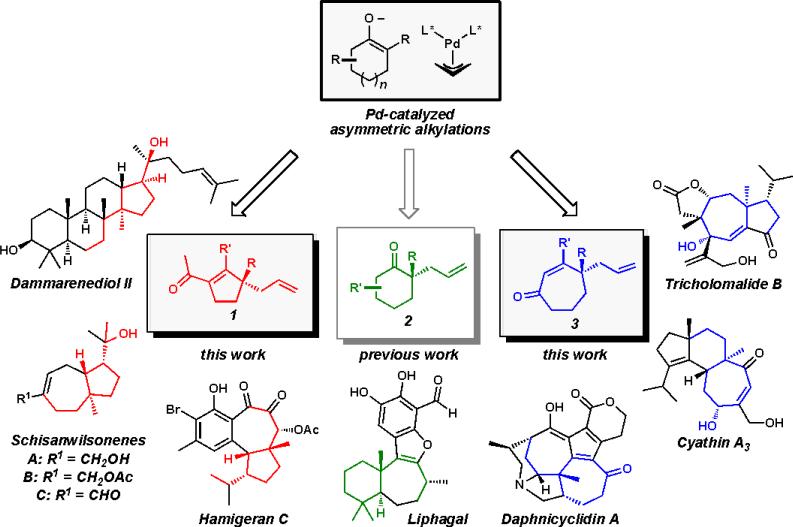

Guided by our continuing interest in the preparation of polycyclic systems bearing all-carbon quaternary stereocenters using Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation chemistry,ii,iii,iv we sought to prepare various chiral cyclic ketone building blocks for total synthesis. Our investigation of six-membered ring substrates has allowed us to achieve the total synthesis of a number of complex natural products.v Given our earlier success, we aimed to generalize our approach and gain access to natural products containing chiral cyclopentanoid and cycloheptanoid ring systems as a part of a broader synthetic strategy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Application of cyclopentanoid, cyclohexanoid, and cycloheptanoid cores toward stereoselective natural product total synthesis.

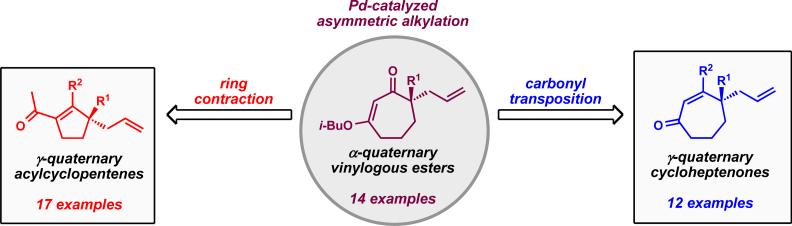

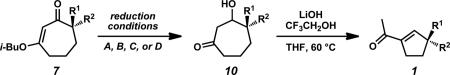

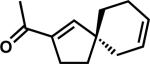

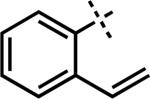

Our efforts led to the development of general strategies for the preparation of α-quaternary vinylogous esters and their conversion to γ-quaternary cycloheptenones using Stork–Danheiser transformations (Figure 2).vi During the course of this work, we observed the unusual reactivity of β-hydroxycycloheptanones and exploited a two-carbon ring contraction to provide a general synthesis of γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes.vii With access to the isomeric five- and seven-membered enones, we prepared diverse synthetic derivatives and polycyclic systems that can potentially provide different entry points for synthetic routes toward complex natural products.

Figure 2.

General access to enantioenriched cyclopentanoid and cycloheptanoid cores.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. β-Ketoester synthesis and Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation reactions

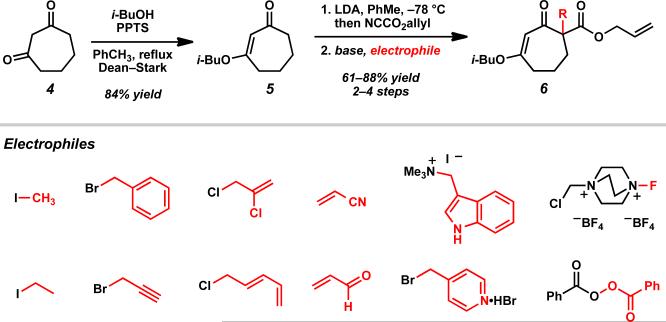

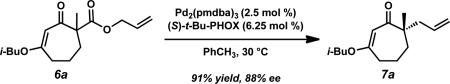

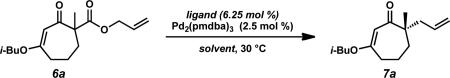

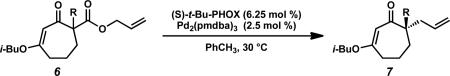

Much of our past research on the asymmetric alkylation of cyclic ketonesiia,iii,viiid and vinylogous estersvb–e,viiia–c,e focused on six-membered rings, while transformations of larger rings were less thoroughly investigated. We hoped to extend our work by exploring asymmetric alkylations of seven-membered vinylogous esters. The feasibility of various types of substrates for our asymmetric alkylation chemistry suggested that vinylogous ester 5 can be transformed into silyl enol ether, enol carbonate, or β-ketoester substrates, but we chose to prepare β-ketoesters due to their relative stability and ease of further functionalization. To access a variety of racemic α-quaternary β-ketoester substrates for Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation reactions, we required multi-gram quantities of 1,3-cycloheptanedione (4). Dione 4 is commercially available,ix but we typically prepare it from cyclopentanone by the route of Ragan and co-workers to facilitate large-scale synthesis.x Treatment of 4 with i-BuOH and catalytic PPTS under Dean–Stark conditions produced vinylogous ester 5 (Scheme 1).ix Acylation of 5 with allyl cyanoformate following deprotonation with LDA enabled facile installation of the requisite allyl ester functionality. Subsequent enolate trapping with a variety of electrophiles under basic conditions provided substrates containing alkyl, alkyne, alkene, 1,3-diene, vinyl chloride, nitrile, heteroarene, aldehyde, fluoride, silyl ether, and ester functionalities in 61–88% yield over two to four steps (6a–n). With these quaternary β-ketoesters in hand, we evaluated the scope of Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation reactions on seven-membered ring vinylogous ester substrates, focusing on methyl/allyl substituted 6a for our optimization efforts.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of parent vinylogous ester 5 and β-ketoester substrates 6.

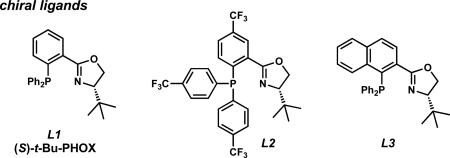

A survey of several electronically differentiated PHOX ligandsiia,xi combined with Pd2(pmdba)3xii,xiii in a number of different solvents using methyl-substituted β-ketoester 6a identified the optimal parameters for this transformation (Table 1). Initial conditions employed (S)-t-Bu-PHOX (L1, 6.25 mol %) and Pd2(pmdba)3 (2.5 mol %) in THF and gave vinylogous ester 7a in 94% yield and 84% ee (entry 1).xiv Application of the same catalyst system in other ethereal solvents such as 1,4-dioxane, 2-methyl THF, TBME, and Et2O led to only slight improvements in the enantioselectivity of the reaction to give the desired product in up to 86% ee (entries 2–5). Switching to aromatic solvents provided modest increases in asymmetric induction, furnishing 7a in 91% yield and 88% ee in the case of toluene (entries 6–7).

Table 1.

Solvent and ligand effects on enantioselective decarboxylative allylation.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ligand | solvent | yieldb(%) | eec(%) |

| 1 | L1 | THFe | 94 | 84 |

| 2 | L1 | 1,4-dioxane | 86 | 84 |

| 3 | L1 | 2-methyl THFe | 75 | 85 |

| 4 | L1 | TBMEe | 88 | 85 |

| 5 | L1 | Et2O | 93 | 86 |

| 6 | L1 | PhH | 84 | 86 |

| 7 | L1 | PhCH3 | 91 | 88 |

| 8d | L2 | PhCH3 | 57 | 90 |

| 9 | L3 | PhCH3 | 77 | 72 |

Conditions: β-ketoester 6a (1.0 equiv), Pd2(pmdba)3 (2.5 mol %), ligand (6.25 mol %) in solvent (0.1 M) at 30 °C; pmdba = 4,4’-methoxydibenzylideneacetone.

Isolated yield.

Determined by chiral HPLC.

Increased catalyst loadings were required to achieve full conversion: Pd2(pmdba)3 (5 mol %), L2 (12.5 mol %).

THF = tetrahydrofuran, TBME = tert-butyl methyl ether, 2-methyl THF = 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran.

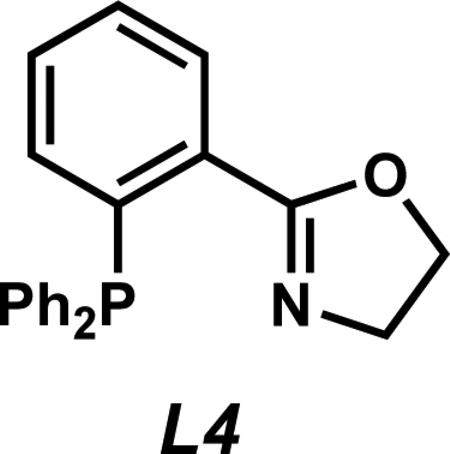

We next examined the impact of other PHOX ligands (L2 and L3) in this medium. Electron deficient ligand L2xv displayed improved enantioselectivity at the cost of higher catalyst loading and lower yield (entry 8). Structural modification of the aryl phosphine backbone was evaluated with ligand L3, but this proved to be less effective, giving reduced yield and ee (entry 9). Of the three ligands, L1 furnished the best overall results.

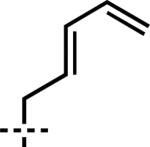

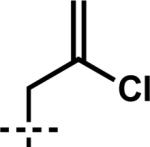

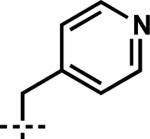

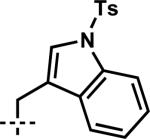

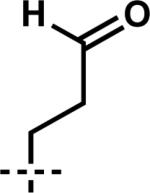

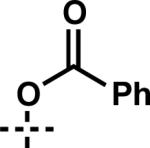

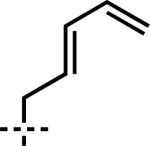

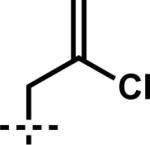

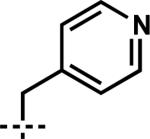

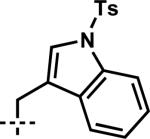

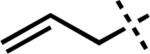

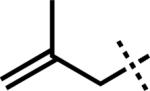

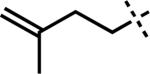

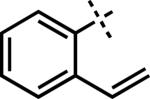

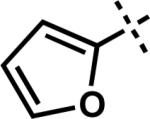

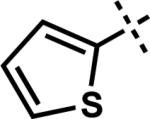

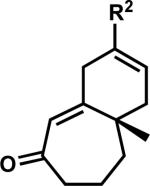

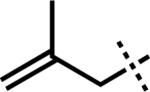

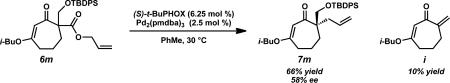

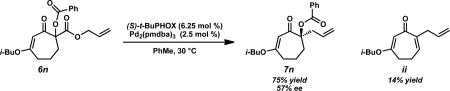

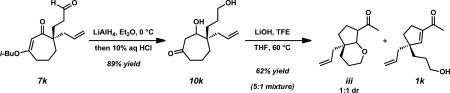

With optimal ligand and solvent conditions in hand, we explored asymmetric alkylation reactions of a variety of α-substituted β-ketoesters (Table 2). Simple alkyl substitution performed well under our standard conditions (entries 1–2). A variety of aromatic and heteroaromatic functionality was well tolerated under the reaction conditions (entries 3, 9–10). Additionally, unsaturated functionality such as alkynes, alkenes, and 1,3-dienes did not suffer from competitive reaction pathways (entries 4–6). In the case of vinyl chloride 6g, no products derived from oxidative addition into the C–Cl bond were observed (entry 7). Gratifyingly, N-basic functionality such as nitriles and pyridines could be carried through the reaction without noticeable catalyst poisoning (entries 8–9). Perhaps the most intriguing result was the observation that an unprotected aldehyde could be converted to the enantioenriched product 7k in 90% yield and 80% ee, highlighting the essentially neutral character of the reaction conditions (entry 11). Tertiary fluoride products could also be obtained efficiently in 94% yield and 91% ee (entry 12). Although most substrates underwent smooth asymmetric alkylation, several substrates such as silyl ether 6mxvi and benzoate ester 6nxvii were not formed as efficiently under the reaction conditions due to unproductive side reactions (entries 13–14).

Table 2.

Scope of the Pd-catalyzed enantioselective alkylation of cyclic vinylogous esters.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate 6 | R | product 7 | yieldb(%) | eec(%) |

| 1 | 6a | –CH3 | 7a | 91 | 88 |

| 2 | 6b | –CH2CH3 | 7b | 89 | 92 |

| 3 | 6c | –CH2Ph | 7c | 98 | 86 |

| 4 | 6d | –CH2C≡CH | 7d | 88 | 89 |

| 5 | 6e | –CH2CH2CH=CH2 | 7e | 95 | 87 |

| 6 | 6f |

|

7f | 90 | 90 |

| 7 | 6g |

|

7g | 99 | 86 |

| 8 | 6h | –CH2CH2CN | 7h | 96 | 87 |

| 9 | 6i |

|

7i | 97 | 85 |

| 10 | 6j |

|

7j | 98 | 83 |

| 11 | 6k |

|

7k | 90 | 80 |

| 12 | 61 | –F | 71 | 94 | 91 |

| 13 | 6m | –CH2OTBDPSd | 7m | 66 | 58 |

| 14 | 6n |

|

7n | 75 | 57 |

Conditions: β-ketoester 6 (1.0 equiv), Pd2(pmdba)3 (2.5 mol %), (S)-t-Bu-PHOX (L1, 6.25 mol %) in PhCH3 (0.1 M) at 30 °C; pmdba = 4,4’-methoxydibenzylideneacetone.

Isolated yield.

Determined by chiral HPLC or SFC.

TBDPS = tert-butyldiphenylsilyl, Ts = 4-toluenesulfonyl.

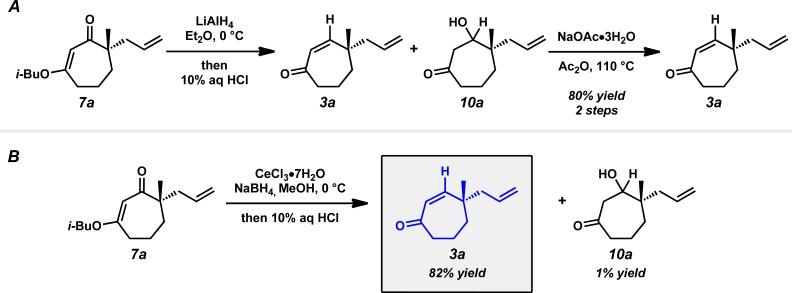

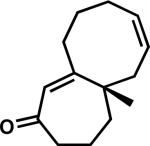

2.2. Observation of unusual reactivity of β-hydroxycycloheptanones

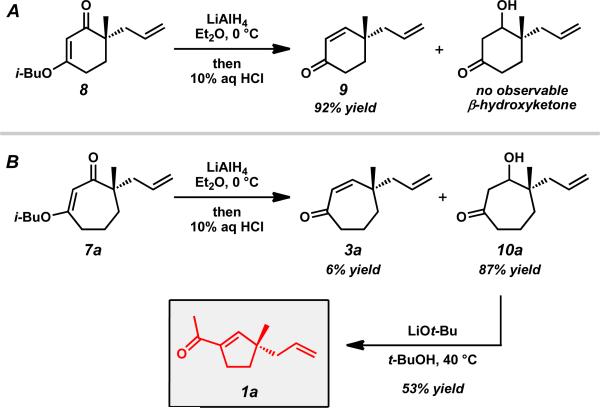

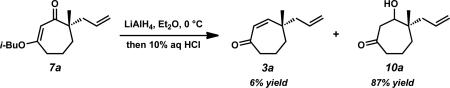

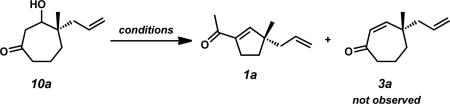

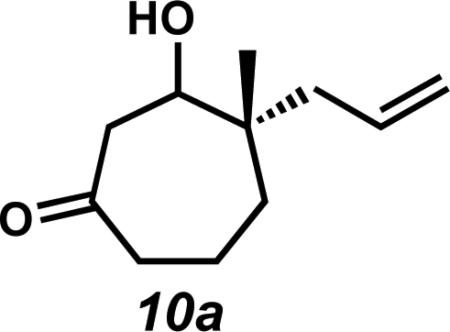

With an assortment of asymmetric alkylation products in hand, we next sought to perform a carbonyl transposition using methods developed by Stork and Danheiser.xviii Earlier experiments on the hydride reduction of six-membered vinylogous ester 8 with subsequent acid treatment gave enone 9 as expected (Scheme 2A). However, to our surprise, application of identical reaction conditions to the seven-membered analog (7a) gave poor yields of cycloheptenone 3a (Scheme 2B). Only minor quantities of elimination product were observed even after prolonged stirring with 10% aqueous HCl. Closer inspection of the reaction mixture revealed β-hydroxyketone 10a as the major product, suggesting that these seven-membered rings display unique and unusual reactivity compared to their sixmembered ring counterparts.xix,xx,xxi

Scheme 2.

Observation of the unusual reactivity of β-hydroxycycloheptanone 7a.

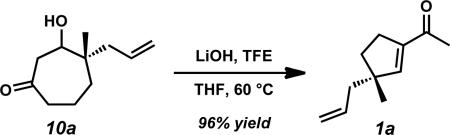

Without initial success using acidic conditions, we reasoned that β-hydroxyketone 10a could potentially provide cycloheptenone 3a under basic conditions through a β-elimination pathway (Scheme 2B). Attempts in this regard did not produce enone 3a, but instead gave isomeric enone 1a that appeared to be formed through an unexpected ring contraction pathway.xxii Notably, this transformation serves as a rare example of a two-carbon ring contraction.xx,xxiii,xxiv

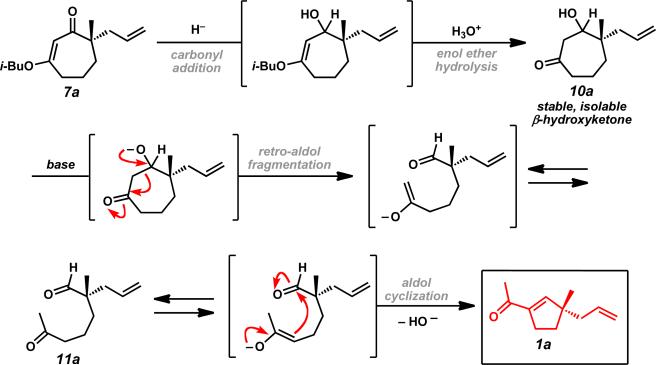

Upon consideration of the reaction mechanism, we believed that this process occurred through an initial deprotonation of the hydroxy moiety, followed by retro-aldol ring fragmentation to a ketoaldehyde enolate (Scheme 3). Subsequent isomerization to the more substituted enolate and aldol cyclization could lead to the observed two-carbon ring contraction product 1a. Attempts to isolate the intermediate ketoaldehyde 11a were unsuccessful, but aldehyde peaks could be observed by 1H NMR in reactions that did not proceed to full conversion. Subsequent experiments on more substituted β-hydroxyketones enabled isolation of linear uncyclized intermediates and provided additional support for this reaction mechanism (Scheme 6).

Scheme 3.

Proposed ring contraction mechanism.

Scheme 6.

Ring contraction screen on β-hydroxyketone 10r.

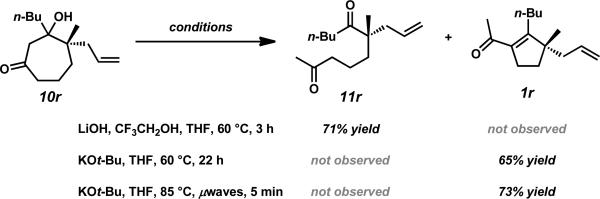

To explore the general stability and reactivity of β-hydroxycycloheptanones, we examined simplified analogs that do not possess the α-quaternary stereocenter. (Scheme 4). Following hydride reduction, elimination to cyclohexenone 13 was observed for the six-membered vinylogous ester 12, while β-hydroxycycloheptanone 15 and volatile cycloheptenone 14 were observed for seven-membered analog 5. In the seven-membered ring case, a higher proportion of elimination product was observed when compared to the more substituted analog. A milder aqueous acid work-up may suffice to hydrolyze the isobutyl enol ether and enable isolation of the β-hydroxycycloheptanone in higher yield in this case. The ring contraction of β-hydroxycycloheptanone 15 under basic conditions proceeded smoothly to give volatile acylcyclopentene 16. These observations suggest that the unusual two-carbon ring contraction appears to be a general phenomenon related to seven-membered rings and motivated the development of the ring contraction chemistry as a general approach to obtaining chiral acylcyclopentene products.

Scheme 4.

Attempted Stork–Danheiser manipulations on unsubstituted rings.

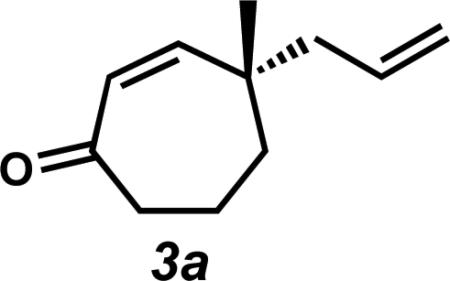

2.3. Ring contraction strategy for preparing γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes

Intrigued by our findings, we sought to develop a robust route to γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes with many substitution patterns. Exploring a number of bases, additives, solvents, and temperatures for the ring contraction of β-hydroxyketone 10a provided insight into the optimal parameters for the transformation (Table 3). Given our early result using LiOt-Bu, we examined numerous aldol cyclization conditions with a variety of non-nucleophilic bases. We observed that several t-butoxides in t-BuOH and THF gave conversion to the desired product (1a) in good yields (entries 1–4), but noted that the rate of product formation was comparatively slower with LiOt-Bu than with NaOt-Bu or KOt-Bu. The use of various hydroxides revealed a similar trend, where NaOH and KOH generated acylcyclopentene 1a in 4 hours with improved yields over their respective t-butoxides (entries 5 and 6). The relatively sluggish reactivity of LiOH may be due to the lower solubility of this base in THF, providing 1a in low yield with the formation of various intermediates (entry 7).

Table 3.

Ring contraction reaction optimization.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | base | additive | solvent | T (°C) | yieldb(%) |

| 1 | LiOt-Bu | — | t-BuOH | 40 | 71 |

| 2 | LiOt-Bu | — | THF | 40 | 60 |

| 3 | NaOt-Bu | — | THF | 40 | 81 |

| 4e | KOt-Bu | — | THF | 40 | 85 |

| 5 | NaOH | — | THF | 60 | 89 |

| 6 | KOH | — | THF | 60 | 87 |

| 7 | LiOH | — | THF | 60 | 19d |

| 8 | LiOH | t-BuOH | THF | 60 | 78 |

| 9 | LiOH | HFIPc | THF | 60 | 87 |

| 10 | LiOH | TFEc | THF | 60 | 96 |

| 11 | LiOCH2CF3 | — | THF | 60 | 90e |

| 12 | CsOH·H2O | — | THF | 60 | 48 |

| 13 | Cs2CO3 | — | THF | 60 | 61f |

| 14 | Cs2CO3 | TFEc | THF | 60 | 86 |

| 15 | Cs2CO3 | TFEc | CH3CN | 60 | 100 |

Conditions: β-hydroxyketone 10a (1.0 equiv), additive (1.5 equiv), base (1.5 equiv), solvent (0.1 M) at indicated temperature for 9–24 h.

GC yield using an internal standard at ≥ 98% conversion unless otherwise stated.

HFIP = 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol; TFE = 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol.

Several reaction intermediates observed by TLC and GC analysis; proceeded to 78% conversion.

Isolated yield.

Reaction did not reach completion at 24 h; proceeded to 67% conversion.

To improve the yield of the reaction with LiOH as base, we investigated the effect of alcohol additives to facilitate the production of mild, organic-soluble bases under the reaction conditions to increase the efficiency of the transformation. The combination of t-BuOH and LiOH in THF increased the yield of 1a to a similar level as that observed with LiOt-Bu, although the reaction still proceeded slowly (entry 8). Application of more acidic, non-nucleophilic alcohols such as hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and trifluoroethanol (TFE) demonstrated exceptional reactivity in combination with LiOH and efficiently afforded 1a in high yields (entries 9 and 10).xxv In particular, TFE enabled the production of 1a in 96% yield. Comparable results with preformed LiOCH2CF3xxvi suggest that this alkoxide is the active base under the LiOH/TFE ring contraction conditions (entry 11).

Concurrent investigation of cesium bases reinforced the importance of alcohol additives for the in situ formation of organic-soluble bases in ring contraction reactions. With CsOH•H2O and Cs2CO3, product formation was inefficient due to low yield or sluggish reactions (entries 12–13). The addition of TFE afforded acylcyclopentene 1a in yields comparable to those of the LiOH/TFE conditions (entry 14). Notably, ring contraction with Cs2CO3/TFE can also be performed in acetonitrile as an alternative, non-ethereal solvent with high efficiency (entry 15).xxvii

While a number of bases are effective for the production of 1a in excellent yields, we selected the combination of LiOH/TFE as our standard conditions for reaction scope investigation due to the lower cost and greater availability of base. The data from our study further recognize the unique properties of these mild bases and suggest their application may be examined in a broader context.xxviii Importantly, none of the conditions surveyed for the ring contraction studies generated the β-elimination product, cycloheptenone 3a.

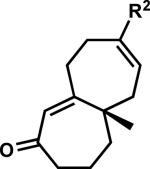

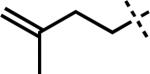

With the optimal base promoted conditions in hand, we investigated the scope of the ring contraction chemistry with a variety of substitution patternsxxi (Table 4). Simple alkyl, aromatic, heteroaromatic substitution performed well under our standard conditions (Method A) in 84–95% yield (entries 1–6, 10). Additionally, vinyl chlorides, nitriles, and indoles could be incorporated into the target acylcyclopentenes in 85–92% yield (entries 7–8). Further studies revealed that alternative aluminum hydrides such as DIBAL could be employed in the generation of the intermediate β-hydroxyketone by enabling more precise control of hydride stoichiometry. The use of these modified conditions followed by oxalic acid work-up in methanol (Method B) facilitated the preparation of pyridine-containing acylcyclopentene 1i in higher yield compared to Method A (entry 9).

Table 4.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate 7 | reduction conditions | R1 | R2 | product 1e | yield (%)f |

| 1 | 7a | A | –CH3 | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1a | 84 |

| 2 | 7b | A | –CH2CH3 | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1b | 90 |

| 3 | 7c | A | –CH2Ph | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1c | 86 |

| 4 | 7d | A | –CH2C≡CH | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1d | 95 |

| 5 | 7e | A | –CH2CH2CH=CH2 | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1e | 87 |

| 6 | 7f | A |

|

–CH2CH=CH2 | 1f | 91 |

| 7 | 7g | A |

|

–CH2CH=CH2 | 92 | |

| 8 | 7h | A | –CH2CH2CN | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1h | 85 |

| 9 | 7i | B |

|

–CH2CH=CH2 | 1i | 80 |

| 10 | 7j | A |

|

–CH2CH=CH2 | 1j | 87 |

| 11 | 7m | C | –CH2OTBDPSi | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1m | 91 |

| 12 | 7o g | C | –(CH2)3OTBDPSi | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1o | 85 |

| 13 |

|

A |

|

1p | 81 | |

| 14 |

|

A |

|

1q | 87 | |

| 15 | 7n | D | –OH | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1n | 25 |

| 16 | 7l | A | –F | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1l | 0 |

Reduction Conditions A: vinylogous ester 7 (1.0 equiv), LiAlH4 (0.55 equiv) in Et2O (0.2 M) at 0 °C, then 10% aqueous HCl quench.

Reduction Conditions B: 1) vinylogous ester 7 (1.0 equiv), DIBAL (1.2 equiv) in PhCH3 (0.03 M) at –78 °C; 2) oxalic acid·2H2O in MeOH (0.02 M).

Reduction Conditions C: vinylogous ester 7 (1.0 equiv), CeCl3·7H2O (1.0 equiv), NaBH4 (3.0 equiv) in MeOH (0.02 M) at 0 °C, then 10% aqueous HCl in Et2O at 0 °C.

Reduction Conditions D: vinylogous ester 7 (1.0 equiv), DIBAL (3.3 equiv) in PhCH3 (0.03 M) at –78 °C; 2) 10% aqueous HCl in Et2O at 0 °C.

Ring Contraction Conditions: β-hydroxyketone 10 (1.0 equiv), CF3CH2OH (1.5 equiv), LiOH (1.5 equiv) in THF (0.1 M) at 60 °C.

Isolated yield over 2-3 steps.

Prepared from 7k.

h Prepared from 7a.

TBDPS = tert-butyldiphenylsilyl, Ts = 4-toluenesulfonyl, DIBAL = diisobutylaluminum hydride.

While various compounds could undergo the ring contraction sequence with high efficiency, other substrates with more sensitive functionality proved to be more challenging. To this end, we investigated the use of milder reduction conditions developed by Luchexxix to further increase the reaction scope. Silyl ether substrate 7mxxx could be converted to the corresponding acylcyclopentene 1m in 86% yield using the LiAlH4 protocol (Method A), but application of Luche reaction conditions using (Method C) enabled an improvement to 91% yield (entry 11). The same conditions provided the related silyl ether-containing acylcyclopentene 1o with a longer carbon chain in 85% yield (entry 12).

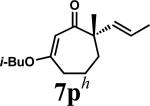

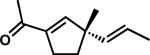

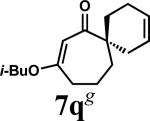

Our success in performing ring contractions with a variety of substituents at the quaternary stereocenter encouraged studies aimed at determining whether additional substitution patterns could be introduced into the acylcyclopentene products. While most substrates involved a variable group and an allyl fragment positioned on the quaternary center, we were intrigued by the possibility of performing the ring contraction chemistry with other groups. Investigation of methyl and trans-propenyl substituted vinylogous ester 7p using the standard LiOH/TFE conditions showed that the chemistry was unaffected by modification of the allyl fragment, giving product in 81% yield (entry 13). Additionally, evaluation of spirocycle 7q also proceeded without complications and afforded the desired product in 87% yield (entry 14).

Although many compounds performed well in the ring contraction sequence, certain substrates posed significant challenges. Application of DIBAL reduction with 10% aqueous HCl work-up (Method D) and ring contraction of α-benzoate ester 7n enabled access to tertiary hydroxyl acylcyclopentene 1n, but the yield was relatively low in comparison to other substrates (entry 15). Attempts to prepare the corresponding tertiary fluoride 7l were unsuccessful as no desired product was observed (entry 16). Under the reaction conditions, both vinylogous esters led to more complex reaction mixtures from unproductive side reactions in contrast to the typically high yielding transformations observed for other substrates.

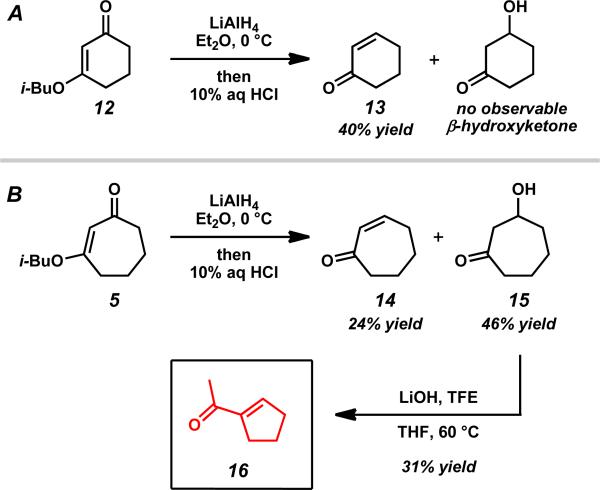

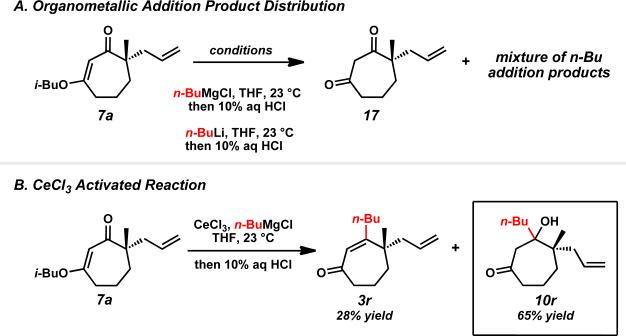

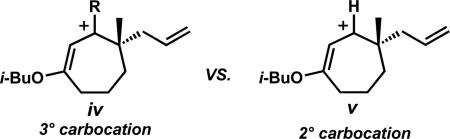

To obtain more functionalized acylcyclopentene products and extend our methodology, we sought access to β-substituted acylcyclopentenes by replacing the hydride reduction step with the addition of an organometallic reagent and applying the ring contraction chemistry on the resulting tertiary β-hydroxyketones. We selected a simple system for our initial investigations and evaluated the reaction of n-butyl nucleophiles with vinylogous ester 7a. Unfortunately, the addition of n-BuMgCl or n-BuLi afforded a complex mixture of products and proceeded slowly without reaching completion, consequently converting unreacted starting material to dione 17 upon work-up with strong acid (Scheme 5A).xxxi This low reactivity could be understood from the electron-rich and sterically-crowded nature of the carbonyl electrophile. Gratifyingly, excellent reactivity was achieved by introducing CeCl3 to the reaction with the Grignard reagent,xxxii although a fair amount of the corresponding enone was produced in the transformation (Scheme 5B).xxxiii Nevertheless, the CeCl3 supplemented addition furnished a significantly improved overall yield of addition products with good selectivity for β-hydroxyketone 10r.

Scheme 5.

Organometallic addition to vinylogous ester 7a.

We next examined the ring contraction sequence with β-hydroxyketone 10r (Scheme 6). Treatment of alcohol 10r with the optimized ring contraction conditions using LiOH/TFE yielded linear dione 11r without any of the β-substituted acylcyclopentene. Even though the conditions did not afford the desired product, the isolation of stable uncyclized intermediate 11r supports our proposed retro-aldol fragmentation/aldol cyclization mechanism (Scheme 3). By employing a stronger base such as KOt-Bu, both steps of the rearrangement could be achieved to give acylcyclopentene 1r. Furthermore, significantly reduced reaction times and higher yields were achieved with microwave irradiation.

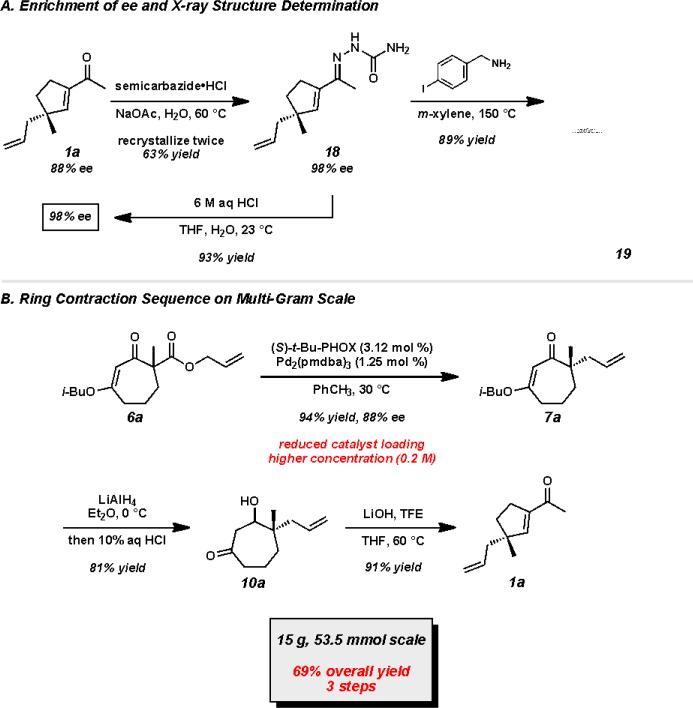

With a route to form a variety of acylcyclopentenes that possess different substitution patterns, we were interested in increasing the enantiopurity of these potentially useful intermediates. Formation of the corresponding semicarbazone 18 enabled us to obtain material in 98% ee after two recrystallizations (Scheme 7A). A high yielding hydrolysis afforded enantioenriched acylcyclopentene 1a. Further functionalization of semicarbazone 18 with 4-iodobenzylamine provided crystals that allowed verification of absolute stereochemistry by X-ray crystallography.xxxiv To demonstrate the viability of our method for large scale asymmetric synthesis, we performed the asymmetric alkylation and ring contraction transformations on multi-gram scale (Scheme 7B). Gratifyingly, our route proved to be robust and reliable. Using 50 mmol of substrate (15 g), we were able to achieve a 94% yield and 88% ee of our desired asymmetric alkylation product. Notably, the increased reaction scale permitted reduced catalyst loadings (1.25 mol % Pd2(pmdba)3 and 3.12 mol % (S)-t-Bu-PHOX, L1) and higher substrate concentrations (0.2 M). β-Ketoester 6a undergoes the asymmetric alkylation and ring contraction protocol to furnish the desired acylcyclopentene in 69% overall yield over the three step sequence.

Scheme 7.

Confirmation of absolute stereochemistry and multi-gram scale reactions.

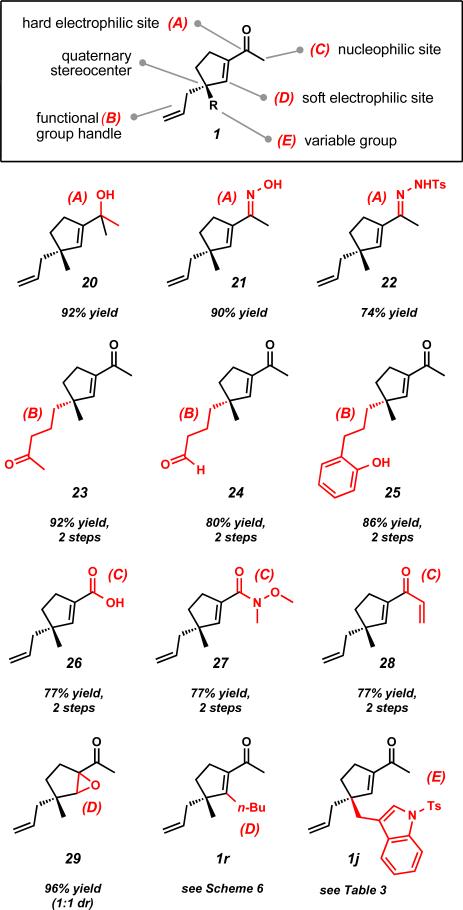

2.4. Synthesis of acylcylopentene derivatives using site-selective transformations

With the ultimate goal of applying our methodology toward the total synthesis of complex natural products, we set out to probe the synthetic utility of various acylcyclopentenes prepared using our ring contraction strategy. While acylcyclopentenes 1 are chiral fragments with low molecular weights, they possess an array of useful functionality that can be exploited for synthetic applications through site-selective functionalizations (Figure 3). Acylcyclopentenes 1 possess hard and soft electrophilic sites, a nucleophilic site, a functional group handle in the form of an allyl group, and a variable group which we can installed through asymmetric alkylation. Additionally, all of the acylcyclopentenes we have prepared bear an all-carbon quaternary stereocenter or a fully substituted tertiary center.

Figure 3.

Selective functionalizations on sites A–E of acylcyclopentenes 1.

We aimed to perform site-selective functionalizations to demonstrate that a variety of derivatives could be prepared by recognizing the rich functionality present in acylcyclopentene 1 (Figure 3). Selective functionalization of site A enabled access to tertiary alcohols, oximes, and hydrazones in 74– 92% yield (20–22). Manipulation of site B through olefin methathesis reactions with methyl vinyl ketone or crotonaldehyde provided intermediate bis-enone or enone-enal systems in 90–95% yield as trans olefin isomers. Chemoselective hydrogenation with Wilkinson's catalyst reduced the less substituted and less sterically hindered olefin in these systems to form mono-enones 23 and 24 in 90– 93% yield. Using the insights gathered from these manipulations, we found it was possible to perform chemoselective Heck and hydrogenation reactions to provide acylcyclopentene 25 bearing a pendant phenol in 86% yield over two steps. Through modification of site C, access to carboxylic acids, Weinreb amides, and divinyl ketones were achieved (26–28). Additionally, functionalization of site D gave rise to epoxide 29. Functionalization of this site was also demonstrated with β-substituted acylcyclopentene 1r (Scheme 6). Lastly, variations at site E were accomplished by installing the appropriate groups at an early stage during the asymmetric alkylation step (Scheme 1 and Table 2).

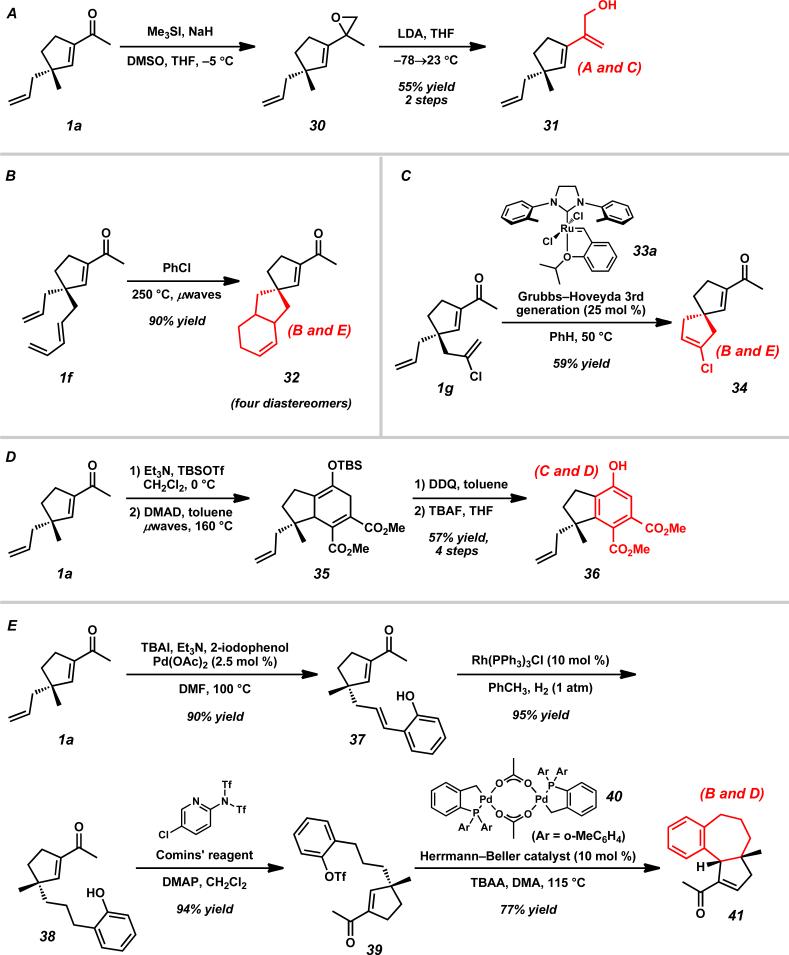

To further increase the potential of these chiral building blocks, we performed manipulations on a combination of sites to arrive at more advanced synthetic intermediates (Scheme 8). Hydroxydiene 31 was obtained from acylcyclopentene 1a by performing a carbonyl epoxidation followed by fragmentation in 55% yield over two steps (Scheme 8A). Spirocyclic systems such as enones 32 and 34 can be obtained by performing an intramolecular Diels–Alder using 1f or a ring closing metathesis of 1g using Grubbs–Hoveyda 3rd generation catalyst (Scheme 8B and 8C). Additionally, phenolic indane 36 was generated in 57% yield over four steps by exploiting an intermolecular Diels–Alder reaction with DMAD (Scheme 8D). To arrive at synthetic intermediates that bear a stronger resemblance to natural products, we formed the triflate of Heck product 39 using Comins’ reagentxxxv and subjected the compound to an intramolecular Heck reaction using the Herrmann–Beller's palladacycle 40xxxvi to obtain tricycle 41 with the cis-ring fusion (Scheme 8E). This key tricycle contains all of the carbocyclic core of hamigerans C and D with correct stereochemistry at the ring fusions.

Scheme 8.

Functionalization of multiple acylcyclopentene reactive sites.

Overall, our general strategy has enabled the synthesis of valuable chiral building blocks by taking advantage of the rich functional group content embedded in acylcyclopentenes 1. Site-selective manipulations on regions A–E can produce monocyclic and polycyclic compounds with a large degree of structural variation. Our studies have provided valuable insight into the nature of these compounds and we aim to apply our knowledge of these promising synthetic intermediates in the total synthesis of complex natural products.

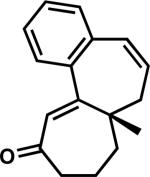

2.5. Carbonyl transposition approach to γ-quaternary cycloheptenones

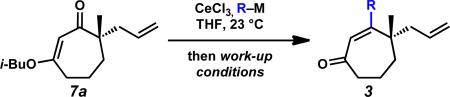

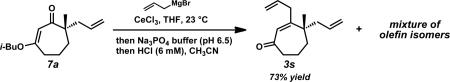

While pleased to discover the unusual reactivity of vinylogous esters 7 that led to the synthesis of various acylcyclopentenes, we maintained our interest in preparing enantioenriched γ-quaternary cycloheptenones and began reexamining reaction parameters to this end. Initially, we identified conditions to obtain cycloheptenone 3a in two steps by activation and elimination of the hydroxy group at elevated temperatures, but ultimately desired a more direct route from vinylogous ester 7a (Scheme 9A). After considerable experimentation, we discovered fortuitously that reduction and elimination using Luche conditions effectively furnished enone 3a with minimal β-hydroxyketone 10a (Scheme 9B). A number of factors may contribute to the reversed product distribution, with methanol likely playing a large role.xxxvii With an effective route to enone 3a, we also sought to prepare β-substituted cycloheptenones through the addition of organometallic reagents.

Scheme 9.

Stepwise and one-pot formation of cycloheptenone 3a.

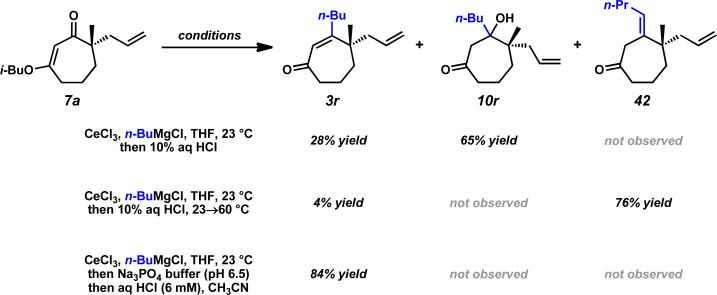

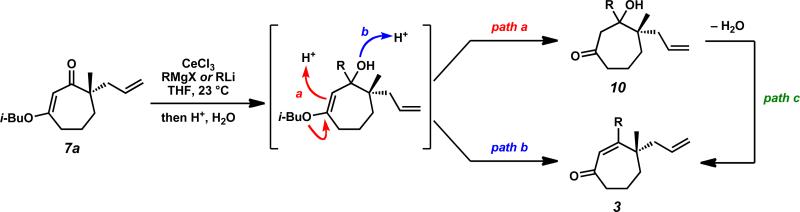

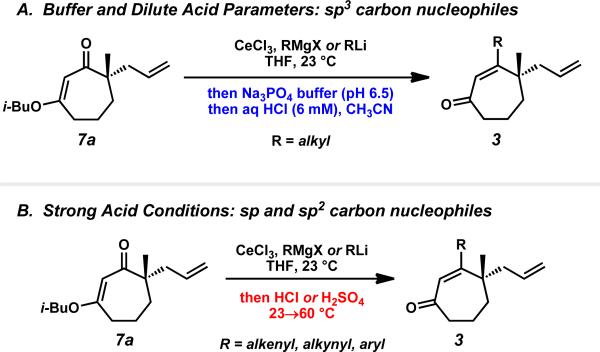

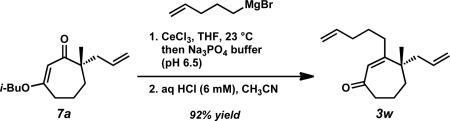

We again investigated the addition of n-BuMgCl to vinylogous ester 7a with CeCl3 additive, focusing on the impact of various quenching parameters. While our previous studies showed that the formation of β-hydroxyketone 10r was favored over cycloheptenone 3r (Scheme 10, and Scheme 11, path a vs. path b), we reasoned that elevated temperatures would promote dehydration of β-hydroxyketone 10 to form cycloheptenone 3 as the major product and simplify the product mixture (Scheme 11, path c). Subsequent heating of the reaction to 60 °C after acid quench led to complete consumption of β-hydroxyketone (Scheme 10). However, the desired cycloheptenone 3r was isolated as a minor product along with the non-conjugated enone 42 in 76% yield as a single olefin isomer. The prevalence of non-conjugated enone 42 again emphasizes the unusual reactivity of these seven-membered ring systems. To revise our approach, we extensively screened mild acidic work-up conditions to minimize the formation of side products such as isomer 42. We ultimately discovered that a sodium phosphate buffer quench followed by treatment of the crude enol etherxxxviii with dilute HCl in acetonitrile exclusively afforded desired cycloheptenone 3r (Scheme 10). Gratifyingly, a number of sp3-hybridized carbon nucleophiles can be employed under these conditions, permitting the preparation of allyl,xxxix homoallyl, and pentenyl substituted cycloheptenones (Table 5, entries 1–6, Method F).

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of β-substituted cycloheptenones.

Scheme 11.

General reaction mechanism for carbonyl transposition.

Table 5.

Scope of organometallic addition/elimination.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | M | work-up conditionsb | product 3 | yieldc(%) |

| 1 |

|

–MgCl | F | 3r | 84 |

| 2 |

|

–MgBr | F | 3s | 73 |

| 3 |

|

–MgBr | F | 3t | 93 |

| 4 |

|

–MgBr | F | 3u | 90 |

| 5 |

|

–MgBr | F | 3v | 82 |

| 6 |

|

–MgBr | F | 3w | 92 |

| 7d |

|

–Li | G | 3x | 84 |

| 8 |

|

–MgBr | H | 3y | 97 |

| 9e |

|

–MgBr | H | 3z | 66 |

| 10 |

|

–Li | G | 3aa | 72 |

| 11 |

|

–MgCl | G | 3ab | 84 |

Conditions: vinylogous ester 7a (1.0 equiv), CeCl3 (2.5 equiv), RMgX or RLi (3.0 equiv) in THF, 23 °C then work-up by Method F, G, or H.

Method F: a) pH 6.5 Na3PO4 buffer b) 6 mM HCl, CH3CN; Method G: 10% w/w aqueous HCl, 60 °C; Method H: 2 M H2SO4, 60 °C.

Yield of isolated product.

Performed without CeCl3 additive.

Product was a 1.9 : 1 mixture of atropisomers.

We then turned our attention to sp- and sp2-hybridized carbon nucleophiles as part of our goal to prepare variably substituted cycloheptenones. Attempts to apply the buffer and dilute acid quenching parameters provided poor selectivity and often led to complex mixtures of products. A thorough evaluation of work-up conditions revealed that the desired unsaturated β-substituted cycloheptenones could be obtained by quenching the reactions with concentrated strong acid followed by stirring at elevated temperatures. Although investigated for sp3-hybridized carbon nucleophiles, the strong acid work-up conditions are more suitable for these reactions because the only possible elimination pathway leads to conjugated enone 3. In this manner, the initial mixture of enone and β-hydroxyketone could be funneled to the desired product (Scheme 11, path b and c). By employing a HCl (Method G) or H2SO4 quench (Method H), the synthesis of vinyl,xl alkynyl,xli aryl, and heteroaryl substituted enones was achieved in moderate to excellent yield (Table 5, entries 7–11). Particularly noteworthy was entry 9, where addition of an ortho-substituted Grignard reagent produced sterically congested cycloheptenone 3z.xlii

These results demonstrate that application of the appropriate quenching parameters based on the type of carbon nucleophile employed is required for successful carbonyl transposition to β-substituted γ-quaternary cycloheptenones (Scheme 12). For sp3-hybridized carbon nucleophiles, reaction work-up with buffer and dilute acid maximizes enone yield and minimizes formation of non-conjugated enone isomers. In contrast, reactions using sp- and sp2-hybridized carbon nucleophiles require strong acidic work-up with heating for best results. Careful application of these general protocols provides access to diverse β-substituted γ-quaternary cycloheptenones.

Scheme 12.

Different work-up conditions for carbonyl transposition reactions employing sp3 vs. sp/sp2 carbon nucleophiles.

2.6. Synthesis of cycloheptenone derivatives using transition-metal catalyzed cyclizations

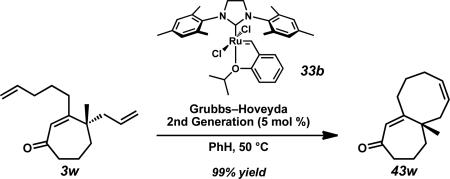

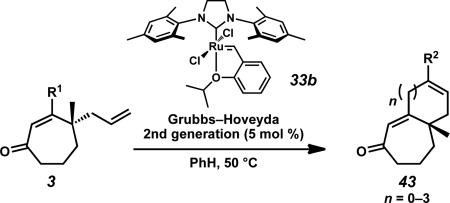

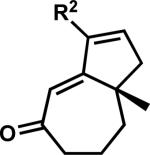

Having produced a variety of cycloheptenones, we next turned our attention to the preparation of a series of bi- and tricyclic structures that would be valuable for total synthesis applications. The incorporation of alkene functionality at the β-position allowed rapid access to a series of [7–n] fused ring systems through ring closing metathesis with the γ-allyl fragment (Table 6). This transformation enables the formation of disubstituted bicycles (43x, 43s, 43u, and 43w) from terminal alkenes in excellent yields (entries 1, 3, 5, and 8). Trisubstituted bicycles (43y, 43t, and 43v) are also accessible through enyne ring-forming metathesis (entry 2) and ring closing metathesis with 1,1-disubstituted alkene β-substituents (entries 4 and 6). Additionally, both atropisomers of cycloheptenone 3z converge to the [7–7–6] tricyclic enone (43z) under the reaction conditions (entry 7).

Table 6.

Formation of bi- and tricyclic systems through ring closing metathesis.a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate 3 | R1 | product 43 | yieldb(%) | ||

| 1c | 3x |

|

|

43x | R2 = H | 93 |

| 2 | 3y |

|

43y |

|

99 | |

| 3d | 3s |

|

|

43s | R2 = H | 91 |

| 4d | 3t |

|

43t | R2 = Me | 90 | |

| 5 | 3u |

|

|

43u | R2 = H | 90 |

| 6 | 3v |

|

43v | R2 = Me | 98 | |

| 7e | 3z |

|

|

43z | 96 | |

| 8 | 3w |

|

|

43w | 99 | |

Conditions: Cycloheptenone 3 (1.0 equiv) and Grubbs–Hoveyda 2nd generation catalyst (33b, 5.0 mol %) in PhH, 50 °C.

Yield of isolated product.

Conditions: Cycloheptenone 3 (1.0 equiv) and Grubbs 2nd generation catalyst (0.2 mol %) in CH2Cl2, reflux.

1,4-benzoquinone (10 mol %) added.

Performed in PhCH3.

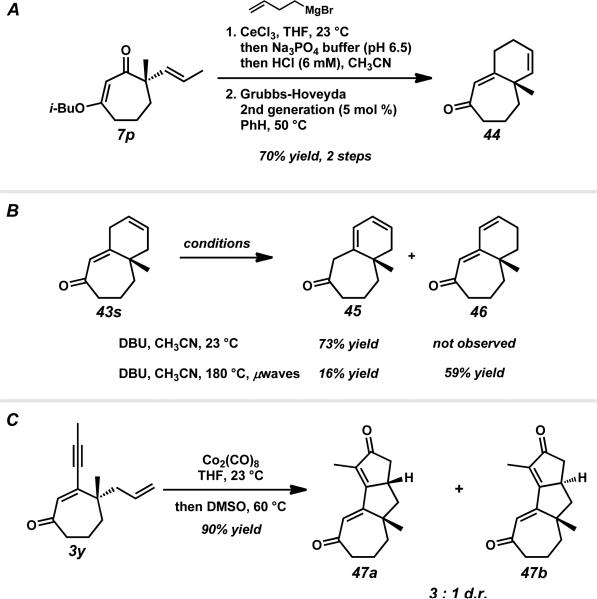

With two [7–6] bicyclic structures in hand, we next investigated the preparation of other such bicycles with variable olefin positions. Addition of 3-butenylmagnesium bromide to trans-propenyl vinylogous ester 7p followed by ring closing metathesis furnished bicycle 44 with the alkene adjacent to the quaternary stereocenter (Scheme 13A). Following the precedent of Fuchs,xliii we envisioned accessing bicycle 46 through a base-mediated migration from enone 43s. However, treatment of skipped diene 43s with an amine base at ambient temperature unexpectedly afforded diene 45 instead (Scheme 13B). In the end, the alkene could be migrated in the desired direction to generate diene 46 by running the reaction in the presence of microwave irradiation. Overall, these methods allow for the preparation of [7–6] bicycles with variable olefin substitution.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of additional [7–6] bicycles and [7–5–5] tricycles.

Recognition of the proximal enyne functionality of cycloheptenone 3y prompted an investigation of a Pauson–Khand reaction to form more complex ring systems. Treatment of enone 3y with dicobalt octacarbonyl in the presence of dimethylsulfoxidexliv generated the [7–5–5] tricycle in a 3:1 diastereomeric ratio of 47a to 47b (Scheme 13C). Overall, our organometallic addition and elimination strategy combined with the appropriate work-up conditions facilitated the preparation of numerous bi- and tricyclic systems with a wide array of substitution patterns that may prove useful in the context of natural product synthesis.

2.7. Unified strategy for the synthesis of complex polycyclic natural products

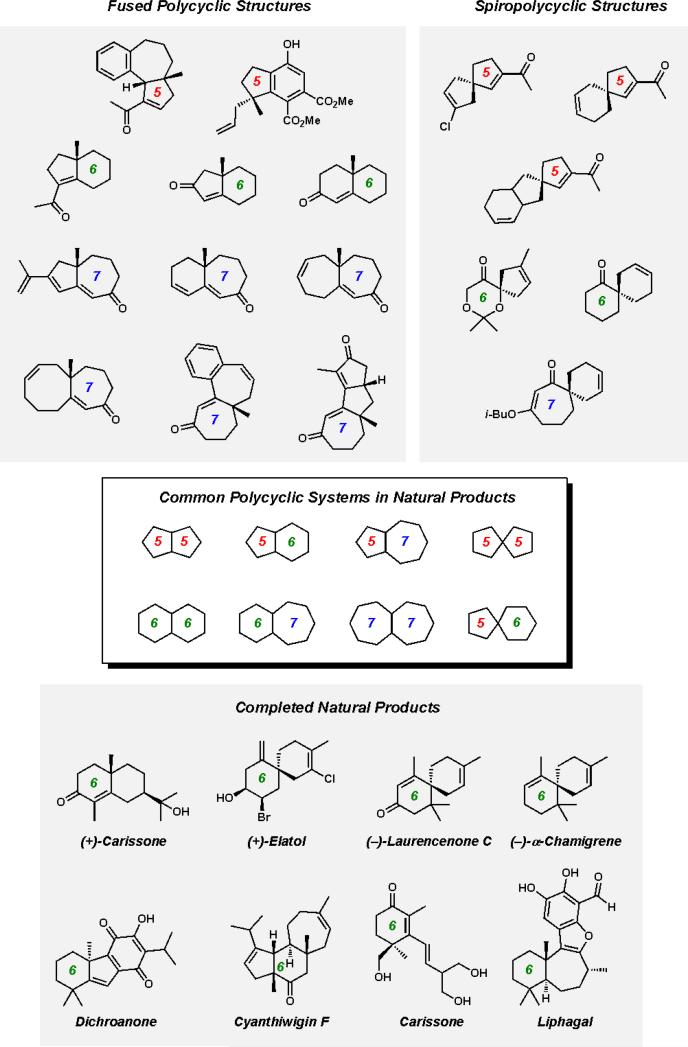

Our divergent approaches to the synthesis of acylcyclopentenes 1 and cycloheptenones 3 from enantioenriched vinylogous esters 7 have provided the foundation for the preparation of complex polycyclic molecules based on cyclopentanoid and cycloheptanoid core structures (Figure 4). Both [5–6] and [5–6–7] fused polycyclic structures could be obtained from acylcyclopentenes. Synthetic elaboration of cycloheptenones provided access to [7–5], [7–6], [7–7], [7–8], [7–7–6], and [7–5–5] fused structures. Additionally, [5–5], [5–6], and [7–6] spirocyclic structures could be obtained using our synthetic approaches. These examples significantly add to the collection of polycyclic architectures accessible by elaboration of chiral six-membered ring carbocycles or heterocycles 2. We have applied previously developed methodology toward a number of polycyclic cyclohexanoid natural products (Figure 4) and similarly plan to exploit the ring contraction and ketone transposition methodology in future efforts toward cyclopentanoid and cycloheptanoid natural products.v The work presented in this report will provide the foundation for future efforts and enable a broader synthetic approach to synthetic targets.

Figure 4.

Representative fused and spirocyclic structures accessible by Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation and successful application to natural product synthesis.

3. Conclusion

We have successfully developed general, enantioselective synthetic routes toward γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes and γ-quaternary cycloheptenones. The key stereoselective component unifying this chemistry is the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of seven-membered vinylogous ester substrates to form α-quaternary vinylogous esters, for which we have demonstrated a broad substrate scope with a variety of all-carbon and heteroatom-containing functionality. These enantioenriched products were transformed in a divergent manner to either facilitate a two-carbon ring contraction to acylcyclopentenes or a carbonyl transposition to cycloheptenones. Further synthetic elaboration of these products has enabled access to five- and seven-membered ring systems that are poised for further functionalization to bi- and tricyclic ring systems. Overall, the described strategies provide broader access to polycyclic ring systems and thus complement our previous work with six-membered ring building blocks. Efforts to expand the scope of these reactions, understand the key reaction mechanisms, and apply the chiral products to the total synthesis of natural products are the subject of future studies.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

Unless otherwise stated, reactions were performed in flame-dried glassware under an argon or nitrogen atmosphere using dry, deoxygenated solvents. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). TLC was performed using E. Merck silica gel 60 F254 precoated glass plates (0.25 mm) and visualized by UV fluorescence quenching, p-anisaldehyde, or KMnO4 staining. SiliaFlash P60 Academic Silica gel (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm) or ICN silica gel (particle size 0.032–0.0653 mm) was used for flash column chromatography. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz, a Varian 400 MR 400 MHz, or a Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer and are reported relative to residual CHCl3 (δ 7.26 ppm). 13C NMR spectra are recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz, a Varian 400 MR 400 MHz, or a Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer (at 75 MHz, 100 MHz, and 125 MHz respectively) and are reported relative to CDCl3 (δ 77.16 ppm). 19F spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz or a Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer (at 282 MHz and 470 MHz respectively) and are reported without the use of a reference peak. IR spectra were obtained using a Perkin Elmer Paragon 1000 or Perkin Elmer Spectrum BXII spectrometer using thin films deposited on NaCl plates and reported in frequency of absorption (cm–1). Optical rotations were measured with a Jasco P-1010 or Jasco P-2000 polarimeter operating on the sodium D-line (589 nm) using a 100 mm path-length cell and are reported as: [α]DT (concentration in g/100 mL, solvent, ee). Analytical chiral HPLC was performed with an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC utilizing a Chiralcel AD or OD-H column (4.6 mm × 25 cm) obtained from Daicel Chemical Industries Ltd. with visualization at 254 nm. Analytical chiral SFC was performed with a Mettler Toledo SFC supercritical CO2 analytical chromatography system with a Chiralcel AD-H column (4.6 mm × 25 cm) with visualization at 254 nm/210 nm. Analytical chiral GC was performed with an Agilent 6850 GC utilizing a G-TA (30 m × 0.25 mm) column (1.0 mL/min carrier gas flow). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained from the Caltech Mass Spectral Facility (EI+ or FAB+) or on an Agilent 6200 Series TOF with an Agilent G1978A Multimode source in electrospray ionization (ESI+), atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI+), or mixed ionization mode (MM: ESI-APCI+).

4.2. Procedures for the synthesis of enantioenriched vinylogous esters 7 using enantioselective decarboxylative alkylation reactions

4.2.1. Vinylogous Ester 7a

Pd2(pmdba)3 (5.0 mg, 4.5 μmol, 2.5 mol %) and (S)-t-Bu-PHOX (4.4 mg, 11 μmol, 6.25 mol %) were placed in a 1 dram vial. The flask was evacuated/backfilled with N2 (3 cycles, 10 min evacuation per cycle). Toluene (1.3 mL, sparged with N2 for 1 h immediately before use) was added and the black suspension was immersed in an oil bath preheated to 30 °C. After 30 min of stirring, β-ketoester 6a (50.7 mg, 0.181 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added as a solution in toluene (0.5 mL, sparged with N2 immediately before use) using positive pressure cannulation. The dark orange catalyst solution turned olive green immediately upon addition of β-ketoester 6a. The reaction was stirred at 30 °C for 21 h, allowed to cool to ambient temperature, filtered through a silica gel plug (2 × 2 cm, Et2O), and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude oil was purified by preparative TLC (SiO2, 4:1 Hexanes:EtOAc) to afford vinylogous ester 7a (38.8 mg, 0.164 mmol, 91% yield, 88% ee) as a pale yellow oil; Rf = 0.31 (3:1 Hexanes:Et2O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.72 (dddd, J = 16.6, 10.5, 7.3, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (s, 1H), 5.05–5.00 (m, 2H), 3.50 (dd, J = 9.3, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (dd, J = 9.3, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 2.53–2.42 (m, 2H), 2.38 (dd, J = 13.7, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.20 (dd, J = 13.7, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (app sept, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 1.86–1.70 (m, 3H), 1.62–1.56 (m, 1H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 206.7, 171.3, 134.6, 117.9, 105.0, 74.5, 51.5, 45.4, 36.1, 35.2, 28.0, 25.2, 19.9, 19.3, 19.3; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 2960, 2933, 2873, 1614, 1470, 1387, 1192, 1171, 998, 912 cm–1; HRMS (EI+) m/z calc'd for C15H24O2 [M]+•: 236.1776; found 236.1767; [α]D25.6 –69.04 (c 1.08, CHCl3, 88.0% ee); HPLC conditions: 1% IPA in Hexanes, 1.0 mL/min, OD-H column, tR (min): major = 6.30, minor = 7.26.

4.3. Procedures for the ring contraction of vinylogous esters 7

4.3.1. General Method A: Lithium Aluminum Hydride Reduction / 10% Aq HCl Hydrolysis

A 500 mL round-bottom flask with magnetic stir bar was charged with Et2O (150 mL) and cooled to 0 °C in an ice/water bath. LiAlH4 (806 mg, 21.2 mmol, 0.55 equiv) was added in one portion. After 10 min, a solution of vinylogous ester 7a (9.13 g, 38.6 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in Et2O (43 mL) was added dropwise using positive pressure cannulation. The grey suspension was stirred for 40 min and additional LiAlH4 (148 mg, 3.9 mmol, 0.10 equiv) was added in one portion. After an additional 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction was quenched by slow addition of aqueous HCl (110 mL, 10% w/w). The resulting biphasic system was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred vigorously for 8.5 h. The phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with Et2O (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was azeotroped with toluene (3 × 20 mL) and purified using flash column chromatography (SiO2, 5 × 15 cm, 9:1→3:1 Hexanes:EtOAc, dry-loaded using Celite) to afford β-hydroxyketone 10a (6.09 g, 33.41 mmol, 87% yield, 1.3:1 dr) as a colorless semi-solid and cycloheptenone 3a (387 mg, 6% yield) as a colorless oil.

4.3.1.1. Cycloheptenone 3a

Rf = 0.54 (7:3 Hexanes:EtOAc); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.04 (dd, J = 12.9, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (dddd, J = 17.1, 10.3, 7.8, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (dddd, J = 10.3, 1.2, 1.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.08–5.03 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.52 (m, 2H), 2.19 (app dd, J = 13.7, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 2.11 (app dd, J = 13.7, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 1.84–1.76 (m, 3H), 1.68–1.63 (m, 1H), 1.10 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.7, 152.5, 133.8, 128.6. 118.6, 47.2, 45.1, 42.7, 38.2, 27.1, 18.4; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 3076, 3011, 2962, 2934, 2870, 1659, 1454, 1402, 1373, 1349, 1335, 1278, 1208, 1172, 997, 916, 874, 822, 772 cm–1; HRMS (EI+) m/z calc'd for C11H16O [M]+• : 164.1201; found 164.1209; [α]D21.0 –9.55 (c 1.07, CHCl3, 88.0% ee).

4.3.1.2. β-Hydroxyketone 10a

Rf = 0.23 (7:3 Hexanes:EtOAc); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ major epimer: 5.88 (dddd, J = 15.1, 9.0, 7.6, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.12–5.08 (m, 2H), 3.70 (dd, J = 4.9, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.86 (dd, J = 15.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.65 (dd, J = 15.6, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.54–2.43 (m, 2H), 2.24 (dd, J = 13.7, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (dd, J = 13.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (dd, J = 15.9, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.82–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.45–1.41 (m, 1H), 0.96 (s, 3H); minor epimer: 5.83 (dddd, J = 14.9, 10.3, 7.6, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.12–5.06 (m, 2H), 3.68 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H) 2.80 (dd, J = 15.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.1 Hz 1H), 2.46–2.38 (m, 2H), 2.18 (dd, J = 13.9, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.09 (dd, J = 12.9, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 1.82–1.65 (m, 3H) 1.50–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.02 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ major epimer: 213.2, 135.0, 118.1, 72.9, 46.7, 44.9, 44.2, 41.0, 36.3, 21.9, 18.9; minor epimer: 212.6, 134.2, 118.3, 73.3, 47.2, 42.8, 41.0, 35.9, 22.6, 18.7; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 3436, 3074, 2932, 1692, 1638, 1443, 1403, 1380, 1352, 1318, 1246, 1168, 1106, 1069, 999, 913, 840 cm–1; HRMS (EI+) m/z calc'd for C11H18O2 [M]+• : 182.1313; found 182.1307; [α]D22.8 –57.10 (c 2.56, CHCl3, 88.0% ee).

4.3.2. General Method E: β-Hydroxyketone Ring Contraction

Alcohol 10a (6.09 g, 33.4 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was dissolved in THF (334 mL) in a 500 mL round-bottom flask. The solution was treated with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (3.67 mL, 50.1 mmol, 1.50 equiv) and anhydrous LiOH (1.20 g, 50.1 mmol, 1.50 equiv). The flask was fitted with a condenser, purged with N2, and heated to 60 °C using an oil bath. After 18 h of stirring, the suspension was allowed to cool to ambient temperature, diluted with Et2O (150 mL), dried over Na2SO4 (30 min of stirring), filtered, and concentrated carefully under reduced pressure, allowing for a film of ice to form on the outside of the flask. The crude product was purified using flash column chromatography (SiO2, 5 × 15 cm, 15:1 Hexanes:Et2O) to afford acylcyclopentene 1a (5.29 g, 32.2 mmol, 96% yield) as a colorless fragrant oil; Rf = 0.67 (8:2 Hexanes:EtOAc); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.45 (app t, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (dddd, J = 16.4, 10.7, 7.3, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.07–5.03 (m, 2H), 2.59–2.48 (m, 2H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.21–2.14 (m, 2H), 1.85 (ddd, J = 12.9, 8.3, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 1.64 (ddd, J = 12.9, 8.5, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 1.11 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 197.5, 151.9, 143.8, 134.9, 117.8, 50.0, 45.3, 36.0, 29.7, 26.8, 25.6; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 3077, 2956, 2863, 1668, 1635, 1616, 1454, 1435, 1372, 1366, 1309, 1265, 1213, 1177, 993, 914, 862 cm–1; HRMS (EI+) m/z calc'd for C11H17O [M+H]+•: 165.1279; found 165.1281; [α]D21.4 +17.30 (c 0.955, CHCl3, 88.0% ee); GC conditions: 80 °C isothermal, GTA column, tR (min): major = 54.7, minor = 60.2.

4.4. Procedures for the carbonyl transposition of vinylogous esters 7

4.4.1. General Method F: Grignard Addition / Na3PO4 Buffer Quench / Dilute HCl Workup

A 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was cycled into a glove box. The flask was loaded with anhydrous cerium chloride (616.2 mg, 2.50 mmol, 2.50 equiv), fitted with a septum, removed from the glove box, and connected to an argon-filled Schlenk manifold. A portion of THF (13 mL) was added, rinsing the cerium chloride to the bottom of the flask. As the resulting thick white slurry was stirred, a solution of pent-4-enylmagnesium bromide (8.6 mL, 0.35 M in THF, 3.01 mmol, 3.01 equiv) was added and the mixture turned grey. After 30 min of stirring, vinylogous ester 7a (236.3 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was cannula-transferred to the slurry from a flame-dried 10 mL conical flask using several THF rinses (3 × 4 mL; total THF added = 25 mL, 0.04 M). TLC analysis indicated that no starting material remained after 5 min. After an additional 10 min of stirring, the reaction was quenched with pH 6.5 Na3PO4 buffer (20 mL). A thick grey emulsion formed. The mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel where the aqueous phase was extracted four times with Et2O. The combined organic (150 mL) were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude oil was transferred to a 20 mL scintillation vial and concentrated under reduced pressure. A stir bar, CH3CN (2.0 mL), and aqueous HCl (2.0 mL, 6 mM) were added to the vial. The resulting cloudy solution was stirred vigorously for 30 min before being transferred to a separatory funnel where the aqueous phase was extracted four times with Et2O. The combined organics (75 mL) were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude oil was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, 3 × 30 cm, 100% Hexanes→1%→2%→5% EtOAc in Hexanes) to afford cycloheptenone 3w (214.2 mg, 0.92 mmol, 92% yield) as a clear colorless oil; Rf = 0.65 (30% EtOAc in Hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.88 (s, 1H), 5.79 (dddd, J = 16.9, 10.2, 6.7, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.67–5.57 (m, 1H), 5.07–4.96 (m, 4H), 2.60–2.53 (m, 2H), 2.35 (dddd, J = 14.1, 6.7, 2.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 2.20–2.04 (m, 5H), 1.83–1.73 (m, 3H), 1.66–1.53 (m, 3H), 1.14 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.3, 162.6, 138.2, 134.1, 128.8, 118.2, 115.3, 45.7, 45.2, 44.3, 38.7, 33.8, 33.5, 29.3, 25.7, 17.6; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 3076, 2975, 2937, 2870, 1652, 1611, 1456, 1415, 1380, 1343, 1257, 1218, 1179, 1110, 1071, 994, 913 cm–1; HRMS (MM: ESI–APCI+) calc'd for C16H25O [M+H]+: 233.1900; found 233.1900; [α]D25.0 –34.96 (c 1.46, CHCl3, 88.0% ee).

4.5. Procedures for synthesis of cycloheptenone derivatives 43

4.5.1. General Method I: Ring Closing Metathesis

A 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, fitted with a water condenser, and connected to a Schlenk manifold (through the condenser) was flame-dried three times, backfilling with argon after each drying cycle. Once cool, the flask was loaded with neat cycloheptenone 3w (50.0 mg, 0.22 mmol, 1.00 equiv) and backfilled with argon twice. Benzene (1 h argon sparge before use, 43 mL, 0.005 M) was added to the flask, followed by Grubbs–Hoveyda 2nd Generation catalyst (6.7 mg, 0.011 mmol, 5 mol %). The solution color turned pale green with addition of catalyst. The flask was lowered into a preheated oil bath (50 °C). The reaction was removed from the oil bath after 30 min, cooled to room temperature (23 °C), and quenched with ethyl vinyl ether (1 mL). The reaction was filtered through a short silica gel plug rinsing with Et2O and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude oil was purified twice by flash chromatography (SiO2, both columns 2 × 28 cm, 100% Hexanes→2%→5% EtOAc in Hexanes) to afford cycloheptenone 43w (43.5 mg, 0.21 mmol, 99% yield) as a yellow oil; Rf = 0.56 (30% EtOAc in Hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.77–5.70 (m, 1H), 5.65 (tdt, J = 10.4, 6.4, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 2.68–2.55 (m, 2H), 2.54–2.44 (m, 1H), 2.30–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.24–2.15 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.04 (m, 1H), 1.94–1.69 (m, 7H), 1.52–1.41 (m, 1H), 1.22 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.2, 165.6, 132.2, 131.9, 128.5, 49.0, 44.2, 39.8, 39.5, 35.5, 31.1, 27.0, 26.5, 17.8; IR (Neat Film NaCl) 3018, 2928, 2859, 1645, 1608, 1468, 1448, 1411, 1380, 1343, 1327, 1279, 1253, 1214, 1178, 1131, 1102, 1088, 1051, 1015, 987, 965, 937, 920, 899, 880, 845, 796, 777, 747 cm–1; HRMS (MM: ESI–APCI+) calc'd for C14H21O [M+H]+: 205.1587; found 205.1587; [α]D25.0 –141.99 (c 1.01, CHCl3, 88% ee).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication is based on work supported by Award No. KUS-11-006-02, made by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). The authors wish to thank NIHNIGMS (R01M080269-01), Amgen, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Caltech for financial support. A.Y.H. thanks Roche for an Excellence in Chemistry Award and Abbott for an Abbott Scholars Symposium Award. M.R.K. acknowledges Eli Lilly for a predoctoral fellowship. T.J. thanks the Danish Council for Independent Research/Natural Sciences for a postdoctoral fellowship. Materia, Inc. is gratefully acknowledged for the donation of metathesis catalysts. Lawrence Henling and Dr. Michael Day are acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic structure determination. The Bruker KAPPA APEXII X-ray diffractometer used in this study was purchased via an NSF CRIF:MU award to Caltech (CHE-0639094). Prof. Sarah Reisman, Dr. Scott Virgil, Dr. Christopher Henry, and Dr. Nathaniel Sherden contributed with helpful discussions. Dr. David VanderVelde and Dr. Scott Ross are acknowledged for NMR assistance. The Varian 400 MR instrument used in this study was purchased via an NIH award to Caltech (NIH RR027690). Dr. Mona Shahgholi and Naseem Torian are acknowledged for high-resolution mass spectrometry assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data. Additional general information, procedures for the synthesis of new compounds and ligands, procedures for General Methods A–I, and reaction screening protocols for asymmetric alkylation and ring contraction; 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and IR spectra for compounds L3, L4, 1n, 6l, 6n, 7l, 7n, 10n, 11r, 15, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24, 28, 42; HPLC traces for vinylogous esters 7l and 7n. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:.

References

- i.For a review discussing our strategy of using natural product structures to drive the development of enantioselective catalysis, see: Mohr JT, Krout MR, Stoltz BM. Nature. 2008;455:323–332. doi: 10.1038/nature07370.

- ii.For examples of asymmetric palladium-catalyzed reactions of cyclic ketone enolates, see: Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15044–15045. doi: 10.1021/ja044812x. Ketone Alkylation.Mohr JT, Behenna DC, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6924–6927. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502018.Mohr JT, Nishimata T, Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11348–11349. doi: 10.1021/ja063335a. Enantioselective Protonation.Marinescu SC, Nishimata T, Mohr JT, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1039–1042. doi: 10.1021/ol702821j.Streuff J, White DE, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Nature Chem. 2010;2:192–196. doi: 10.1038/nchem.518. Conjugate Addition / Enolate Alkylation Cascade.

- iii.For examples of the asymmetric palladium-catalyzed reactions of heterocyclic ketone enolates, see: Seto M, Roizen JL, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:6873–6876. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801424. Dioxanone Alkylation.Behenna DC, Liu Y, Yurino T, White DE, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. 2011. Lactam Alkylation. submitted.

- iv.For studies on the computational and experimental studies on the mechanism of palladium-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation using the PHOX ligand scaffold, see: Keith JA, Behenna DC, Mohr JT, Ma S, Marinescu SC, Oxgaard J, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11876–11877. doi: 10.1021/ja070516j.Sherden NH, Behenna DC, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6840–6843. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902575.

- v.For examples of the asymmetric alkylation of cyclic ketones and vinylogous esters or thioesters in the context of natural product synthesis, see: McFadden RM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7738–7739. doi: 10.1021/ja061853f.White DE, Stewart IC, Grubbs RH, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:810–811. doi: 10.1021/ja710294k.Levine SR, Krout MR, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:289–292. doi: 10.1021/ol802409h.Petrova KV, Mohr JT, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:293–295. doi: 10.1021/ol802410t.White DE, Stewart IC, Seashore-Ludlow BA, Grubbs RH, Stoltz BM. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4668–4686. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.04.128.Day JJ, McFadden RM, Virgil SC, Kolding H, Alleva JL, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:6814–6818. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101842.

- vi.For our initial communication on the addition of organometallic reagents to chiral vinylogous esters to form γ-quaternary cycloheptenones, see: Bennett NB, Hong AY, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1ob06189e. In Press, DOI: 10.1039/C1OB06189E.

- vii.For our initial communication on the palladium catalyzed asymmetric alkylation and ring contraction studies in the synthesis of γ-quaternary acylcyclopentenes, see: Hong AY, Krout MR, Jensen T, Bennett NB, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:2756–2760. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007814.

- viii.Concurrent with our efforts, palladium–catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylations to form enantioenriched α-quaternary cyclic ketones and vinylogous esters/thioesters were reported by Trost. See: Trost BM, Pissot-Soldermann C, Chen I, Schroeder GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4480–4481. doi: 10.1021/ja0497025.Trost BM, Schroeder GM. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:174–184. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400666.Trost BM, Pissot-Soldermann C, Chen I. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:951–959. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400558.Trost BM, Xu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2846–2847. doi: 10.1021/ja043472c.Trost BM, Bream RN, Xu J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:3109–3112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504421.

- ix.1,3-Cycloheptanedione (catalog #515981) and 3-isobutoxy-2-cyclohepten-1-one (catalog #T271322) are commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich. The price of 1,3-cycloheptanedione is $40,000/mol. Adopted from Aldrich August 28th, 2011.

- x.a Ragan JA, Makowski TW, am Ende DJ, Clifford PJ, Young GR, Conrad AK, Eisenbeis SA. Org. Process Res. Dev. 1998;2:379–381. [Google Scholar]; b Ragan JA, Murry JA, Castaldi MJ, Conrad AK, Jones BP, Li B, Makowski TW, McDermott R, Sitter BJ, White TD, Young GR. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2001;5:498–507. [Google Scholar]; c Do N, McDermott RE, Ragan JA. Org. Synth. 2008;85:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- xi.a Tani K, Behenna DC, McFadden RM, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2529–2531. doi: 10.1021/ol070884s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Krout MR, Mohr JT, Stoltz BM. Org. Synth. 2009;86:181–193. doi: 10.15227/orgsyn.086.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.a Ukai T, Kawazura H, Ishii Y, Bonnet JJ, Ibers JA. J. Organometallic Chem. 1974;65:253–266. [Google Scholar]; b Fairlamb IJS, Kapdi AR, Lee AF. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4435–4438. doi: 10.1021/ol048413i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Pd2(pmdba)3 is preferable to Pd2(dba)3 in this reaction for ease of separation of pmdba from the reaction products during purification. pmdba = 4,4’-methoxydibenzylideneacetone.

-

xiv.Racemic products were obtained using Pd(PPh3)4 (5 mol %) or achiral PHOX ligand L4 (6.25 mol %) and Pd2(pmdba)3 (2.5 mol %) in toluene at 30 °C.

- xv.For a preparation of electron-deficient PHOX ligand L2 ((S)-p-(CF3)3-t-Bu-PHOX), see: White DE, Stewart IC, Grubbs RH, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:810–811. doi: 10.1021/ja710294k.McDougal NT, Streuff J, Mukherjee H, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5550–5554. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.08.039.

-

xvi.The reaction with silyl-protected alcohol 6m afforded alkylation product 7m and exocyclic enone i in 10% yield. A related silyl-protected alcohol substrate did not display this type of elimination during an asymmetric decarboxylative alkylation reaction on a six-membered ring β-ketoester substrate. See ref. 2a.

-

xvii.The reaction with benzoate ester 6n afforded alkylation product 7n and endocyclic enone ii in 14% yield.

- xviii.Stork G, Danheiser RL. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1775–1776. [Google Scholar]

- xix.Differences in ring conformational preferences can also be observed in the 1H NMR spectra of 1,3-cyclohexadione (exclusively ketoenol form) and 1,3-cycloheptadione (exclusively diketo form). See ref. 10c.

- xx.For selected examples of the two-carbon ring contraction of seven-membered carbocycles, see: Frankel JJ, Julia S, Richard-Neuville C. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1968:4870–4875.Jun C-H, Moon CW, Lim S-G, Lee H. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1595–1597. doi: 10.1021/ol025816e.

- xxi.Notably, 10a and related β-hydroxyketones 10a–k, 10m–q appear to undergo minimal decomposition after several months of storage at room temperature by TLC and 1H NMR analysis and immediate conversion to acylcyclopentenes 1a is not necessary to achieve high yields.

- xxii.While a recent report shows a single example of a similar β-hydroxyketone, we believe the unusual reactivity and synthetic potential of these compounds has not been fully explored: Rinderhagen H, Mattay J. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:851–874. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304827.

- xxiii.For an example of a photochemical two-carbon ring contraction of a macrocycle, see: Yang Z, Li Y, Pattenden G. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:6546–6549.

- xxiv.For examples of ring contractions of medium-sized ring heterocycles, see: Nasveschuk CG, Rovis T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3264–3267. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500088.Nasveschuk CG, Rovis T. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:612–617. doi: 10.1021/jo702071v.Nasveschuk CG, Rovis T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:240–254. doi: 10.1039/b714881j.Baktharaman S, Afagh N, Vandersteen A, Yudin AK. Org. Lett. 2010;12:240–243. doi: 10.1021/ol902550q.Dubovyk I, Pichugin D, Yudin AK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:5924–5926. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100612.Volchkov I, Park S, Lee D. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3530–3533. doi: 10.1021/ol2013473.Dubinina GG, Chain WJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:939–942.

- xxv.For a discussion of the properties of fluorinated alcohols and their use, see: Begue J-P, Bonnet-Delphon D, Crousse B. Synlett. 2004:18–29.

- xxvi.A lithium alkoxide species is presumably generated in situ based on the following pKa values: (H2O = 15.7, TFE = 12.5, HFIP = 9.3 [water]; H2O = 31.2, TFE = 23.5, HFIP = 18.2 [DMSO]); Bordwell FG. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:456–463.

- xxvii.No reaction was observed with the following bases (with or without TFE additive): DBU, TMG, Na2CO3, BaCO3, and CaH2. DBU = 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene, TMG = 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine.

- xxviii.Fluorinated lithium alkoxides were recently used to promote Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons olefinations of sensitive substrates, demonstrating their mild reactivity: Blasdel LK, Myers AG. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4281–4283. doi: 10.1021/ol051785m.

- xxix.Luche JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:2226–2227. [Google Scholar]

-

xxx.Although we had success in preparing silyloxy acylcyclopentene 1p from vinylogous ester 7p, we wondered whether it would be possible to perform a ring contraction on aldehyde 7k. Under our standard conditions, the intermediate ketodiol 10k can be obtained in 89% yield, however the subsequent ring contraction proceeded in 62% yield to afford a complex mixture of pyran diastereomers iii and uncyclized acylcyclopentene 1k.

- xxxi.Analytically pure samples of dione 17 can be obtained from vinylogous ester 7a by treatment with acid. See Supplementary Data for details.

- xxxii.The addition of cerium chloride to reactions with organolithium or Grignard reagents has been shown to increase reactivity and reduce side reactions with vinylogous ester systems, see: Crimmins MT, Dedopoulou D. Synth. Commun. 1992;22:1953–1958.

-

xxxiii.The increase in enone formation with the organometallic addition is likely due to the higher stability of the tertiary carbocation (iv) compared to the secondary carbocation (v) formed along the reduction pathway.

- xxxiv.Crystallographic data have been deposited at the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK and copies can be obtained on request, free of charge, by quoting the publication citation and the deposition number 686849.

- xxxv.Comins DL, Dehghani A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6299–6302. [Google Scholar]

- xxxvi.Herrmann WA, Brossmer KO, Reisinger C-P, Priermeier T, Beller M, Fischer H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1995;34:1855–1848. [Google Scholar]

- xxxvii.Preferential β-hydroxyketone formation is observed when the acidification of the intermediate isobutyl enol ether is performed in diethyl ether instead of methanol. See Table 4.

- xxxviii.Attempts to purify the crude enol ether were challenging due to decomposition to enone 3r and β-hydroxyketone 10r.

-

xxxix.The yield of cycloheptenone 3s is lower than many related enones due to the formation of several side products presumed to be non-conjugated alkene isomers.

- xl.Synthesis of the simple β-vinyl substituted enone proved challenging due to the formation of a complex product mixture.

- xli.Quenching the alkynyl nucleophile addition with hydrochloric acid provided a complex mixture of products, most notably one with an equivalent of HCl added into the molecule. This issue was resolved by instead using sulfuric acid.

- xlii.Cycloheptenone 3aa is formed as a 1.9 : 1 mixture of atropisomers whose isomeric peaks coalesce in a variable temperature 1H NMR study. See ref. 6 for variable temperature 1H NMR experiment.

- xliii.Jin Z, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5995–5996. [Google Scholar]

- xliv.Chung YK, Lee BY, Jeong N, Hudecek M, Pauson PL. Organometallics. 1993;12:220–223. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.