Abstract

An acute increase in international normalized ratio (INR) to >3.0 in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) can associate with an unexplained acute increase in serum creatinine and accelerated progression of CKD. A subset of these patients have renal tubular obstruction by casts of red blood cells, presumably the dominant mechanism of the acute kidney injury described as warfarin-related nephropathy. Here, we developed an animal model of this acute kidney injury that is based on the 5/6-nephrectomy model to aid future investigation of the pathogenesis of this condition. We found that acute excessive anticoagulation with brodifacoum (“superwarfarin”) increased serum creatinine levels and hematuria in 5/6-nephrectomized rats but not in controls. In addition, morphologic findings in 5/6-nephrectomized rats included glomerular hemorrhage, occlusive red blood cell casts, and acute tubular injury, similar to the biopsy findings among affected patients. Furthermore, in the rat model, we observed an increase in apoptosis of glomerular endothelial cells. In summary, the 5/6-nephrectomy model combined with excessive anticoagulation may be a useful tool to study the pathogenesis of warfarin-related nephropathy.

The significance of this study derives from the fact that this is the first successful attempt to reproduce in an animal model the morphologic findings seen in patients with a newly recognized syndrome of warfarin-related nephropathy (WRN). WRN can have dire consequences, particularly in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. WRN is a not an uncommon complication of warfarin therapy, which is the most commonly used oral anticoagulant in North America.

We recently reported that warfarin therapy can result in acute kidney injury (AKI) by causing glomerular hemorrhage and renal tubular obstruction by red blood cell (RBC) casts.1 Subsequent analysis of 103 patients with CKD revealed that 37% experienced an unexplained increase in serum creatinine (SC) of ≥0.3 mg/dl within 1 week of an international normalized ratio (INR) > 3.0.2 Also, patients with WRN had accelerated progression of CKD, as compared with patients without WRN. Moreover, our recent analysis of more than 15,000 warfarin-treated patients showed that WRN affects approximately 33% of CKD patients and 16% of non-CKD patients who experienced an INR > 3.0.3 We also found that mortality rate in patients with WRN was significantly higher than in patients without WRN.

Hitherto, there is no animal model available to study WRN. The need for an animal model to study WRN is substantial. An animal model could provide a clear understanding of the mechanisms of WRN. It may also provide insights into strategies for WRN prevention and treatment. Herein, we report that excessive anticoagulation in rats with 5/6-nephrectomy, a model of ablative nephropathy, results in increased SC levels and reproduces the morphologic findings found in patients with WRN. In contrast, excessive anticoagulation in control animals was not associated with changes in SC levels, and kidney morphology was unremarkable.

RESULTS

Treatment with Brodifacoum Results in Increased SC in 5/6-Nephrectomy, but Not in Control Rats

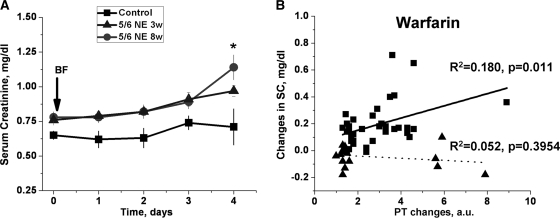

We investigated whether acute excessive anticoagulation induced by brodifacoum (superwarfarin) results in acute kidney injury in experimental animals. Administration of brodifacoum resulted in a significant prothrombin time (PT) increase in each of the 5/6-nephrectomy and control animals. By day 2 there was as much as a 5-fold increase. By day 3, the increase was >10-fold. No animal survived beyond 4 days. In control animals, brodifacoum did not affect SC levels or kidney morphology. In contrast, SC levels significantly increased in 5/6-nephrectomy rats treated with brodifacoum at 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (Figure 1A). Treatment with brodifacoum also resulted in a SC level increase in 5/6-nephrectomy rats if brodifacoum was administered 3 weeks after the ablative surgery, but the SC level increase was lower than in animals treated 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (Figure 1A). To investigate the dose-response relationship between anticoagulation and SC levels, control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats 8 weeks after the ablative surgery were treated with different doses of warfarin. Treatment with warfarin was chosen because (1) treatment with brodifacoum results in a very rapid increase in PT time and it is very difficult to investigate dose-response relationships because there might not be sufficient time for the effects of the coagulopathy on SC to be fully expressed, and (2) mechanisms of action are similar for warfarin and brodifacoum.

Figure 1.

Treatment with brodifacoum (superwarfarin) results in increased SC levels in 5/6-nephrectomy rats but not in controls. Changes in PT are associated with SC level increase in 5/6-nephrectomy rats only. (A) Change in SC after brodifacoum (superwarfarin) treatment. Control rats (n = 9, ■), 5/6-nephrectomy rats at 3 weeks (n = 8, ▴), and 5/6-nephrectomy rats at 8 weeks (n = 10, ●) after the ablative surgery were treated with a single dose of brodifacoum (BF). SC levels were measured before (day 0) and daily after the treatment with brodifacoum (arrow). (B) Animals were treated with different doses of warfarin in drinking water. PT was measured before and after the treatment. A “surrogate” INR was used by comparing PT time after and before the treatment. The average PT time in 50 rats (25 control and 25 5/6-nephrectomy rats) was used as the normal PT time. Changes in SC were calculated from baseline in the same animal. Squares represent 5/6-nephrectomy rats; triangles represent control rats.

For these studies we used a “surrogate” INR by comparing PT time after and before the treatment.4 The average PT time in 50 rats (25 control and 25 5/6-nephrectomy rats) was used as the normal PT time (22.2 seconds). There was no difference between PT time in control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats before warfarin or brodifacoum treatment was initiated (22.30 ± 0.35 seconds versus 22.17 ± 0.39 seconds, respectively, P = 0.8162). Animals treated with different warfarin doses (from 0.25 to 1.0 mg/kg per day) in drinking water for 3 weeks experienced a different PT time increase. As shown in Figure 1B, the increase in PT time was not associated with changes in SC levels in control animals (R2 = 0.052, P = 0.3954), but in 5/6-nephrectomy rats the PT time increase was significantly correlated with changes in SC levels (R2 = 0.180, P = 0.011).

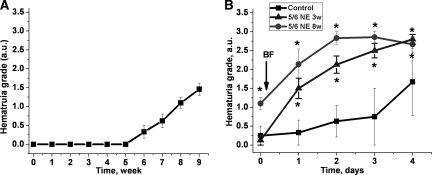

5/6-Nephrectomy Itself Results in Chronic Hematuria

Animals with 5/6-nephrectomy developed progressive hematuria (Figure 2A). As measured by dipstick, no hematuria was seen 3 weeks after the ablative surgery; by 6 weeks after the ablative surgery mild hematuria was noted in approximately one-third of the rats. By 8 weeks after the ablative surgery, mild to moderate hematuria was noted in all 5/6-nephrectomy animals. The hematuria likely is related to the progression of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, which we documented in the 5/6-nephrectomy animals (Table 1). Also, it is well documented that hematuria is a manifestation of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in humans.5,6 We performed light microscopy of the urine sediments of the 5/6-nephrectomy rats 8 weeks after the ablative surgery. This revealed RBCs, but definitive acanthocytes were not seen.

Figure 2.

The ablative surgery results in spontaneous progressive hematuria, which is significantly increased by brodifacoum (superwarfarin) treatment. (A) Changes in hematuria in rats after the ablative surgery (5/6-nephrectomy). Animals at 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery were used for the study. Hematuria was measured using DiaScreen reagent strips. (B) Hematuria was measured before (day 0) and daily after the treatment with brodifacoum (BF, arrow) using DiaScreen reagent strips in control (n = 9, ■), 5/6-nephrectomy 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (n = 10, ●), and 5/6-nephrectomy 3 weeks after the ablative surgery (n = 8, ▴) rats. Hematuria was graded using a semiquantitative scale of 0 to 3+. Score 0 was designated for negative hematuria, score 1+ for mild hematuria, score 2+ for moderate hematuria, and score 3+ for large hematuria. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Table 1.

Morphologic findings in kidneys obtained from animals treated with brodifacoum

| Histologic Parameter | Control (n = 9) | 5/6-Nephrectomy 3 Weeks (n = 8) | 5/6-Nephrectomy 8 Weeks (n = 10) | P (ANOVA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomeruli with global sclerosis (% of glomeruli) | 0 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.20 ± 0.13 | 0.4673 |

| Glomeruli with segmental sclerosis (% of glomeruli) | 0 | 0.25 ± 0.25 | 2.98 ± 0.83a,b | 0.0010 |

| Glomerular enlargement (AU) | 0.11 ± 0.11 | 0.88 ± 0.21a | 1.6 ± 0.18a,b | <0.0001 |

| RBCs in Bowman's space (% of glomeruli) | 0 | 0.69 ± 0.34 | 2.35 ± 0.53a,b | 0.0005 |

| Acute tubular necrosis (AU) | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.21 | 1.6 ± 0.23a,b | <0.0001 |

| Tubular casts (non-RBC casts, % of tubules) | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.11a | 0.0281 |

| Animals with tubular RBCs or tubular RBC casts (% of animals) | 0 | 50 | 100 | n/a |

| RBCs in tubules (% of tubules) | 0 | 0.21 ± 0.19 | 1.21 ± 0.14a,b | <0.0001 |

| RBC casts in tubules (% tubules) | 0 | 1.56 ± 1.22 | 3.94 ± 0.81a | 0.0063 |

| Interstitial fibrosis (AU) | 0 | 0.44 ± 0.11a | 0.70 ± 0.11a | <0.0001 |

| Tubular atrophy (AU) | 0 | 0.44 ± 0.11a | 0.70 ± 0.11a | <0.0001 |

Tubules with RBCs were identified when RBCs were seen in the lumen of tubules without causing luminal occlusion. RBC casts were identified when RBCs in the tubules completely occluded the lumen. Histological findings were scored semiquantitatively for each morphologic change assessed, if possible mostly following the Banff criteria for allograft rejection14 as follows:

Glomerular enlargement—0 to normal (80 to 110 μm diameter); 1+ (mild, up to 25% increase in diameter); 2+ (moderate, 26% to 50% increase in diameter); 3+ (severe, >50% increase in diameter).

Acute tubular necrosis—0 (no acute tubular injury); 1+ (mild patchy acute tubular injury with flattening of the tubular epithelium and/or vacuolization in <25% tubules); 2+ (acute tubular injury in 25% to 50% tubules with scattered tubules containing apoptotic cell debris and/or few granular casts); 3+ (diffuse, >50% tubules with severe acute tubular injury with sloughed off epithelial cells and scattered granular casts in the lumina).

Interstitial fibrosis—0 to normal (up to 5% interstitial fibrosis of the cortical area); 1+ (mild, 6% to 25% of cortical area); 2+ (moderate, 26% to 50% of cortical area); 3+ (severe, >50% of cortical area).

Tubular atrophy—0 to normal (0% to 5% of cortical tubules involved atrophy); 1+ (mild, 6% to 25% of tubules involved); 2+ (moderate, 26% to 50% of tubules involved); 3+ (severe, >50% of cortical tubules involved).

aP < 0.005 compared with control;

bP < 0.05 compared with 5/6-nephrectomy treated with brodifacoum at 3 weeks.

Hematuria was observed after brodifacoum treatment in control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats, but the hematuria increased more slowly and to a lesser degree in the control rats (Figure 2B). As mentioned above, 5/6-nephrectomy rats 8 weeks after the ablative surgery had mild to moderate hematuria, whereas animals 3 weeks after the ablative surgery had no hematuria detected by dipstick. These differences in the degree of hematuria rapidly disappeared after brodifacoum treatment, and already on day 2 after the treatment differences in the degree of hematuria between the 5/6-nephrectomy rats at 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery became minimal (Figure 2B).

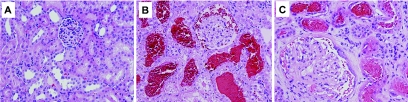

Brodifacoum Coagulopathy Results in Kidney Morphologic Changes Comparable to That Seen in Humans with WRN

Morphologic findings in the kidneys obtained from animals treated with brodifacoum are shown in Table 1. Glomeruli became slightly enlarged already 3 weeks after the ablative surgery; they were mildly to moderately enlarged by 8 weeks after the ablative surgery. The number of glomeruli with segmental sclerosis also progressively increased after the ablative surgery. There were no RBCs seen in Bowman's space or tubules in any of the kidneys obtained from animals not treated with brodifacoum, including control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats.

Treatment with brodifacoum resulted in an increased number of glomeruli with RBCs in Bowman's space and an increase in the number of tubules containing RBCs and RBC casts. This description is relevant only to the 5/6-nephrectomy animals. No RBCs in Bowman's space or RBC tubular casts were seen in control animals treated with brodifacoum (Figure 3). Thus, RBCs in tubules and tubular RBC casts were seen in kidneys in 50% of the rats treated with brodifacoum 3 weeks after the ablative surgery. RBCs and RBC tubular casts were present in 100% of the rats treated with brodifacoum 8 weeks after the ablative surgery. Acute tubular necrosis was also more prominent in rats treated with brodifacoum 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (Table 1). Mononuclear interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrates were only seen in the areas of fibrosis. No active inflammatory lesions were noted. There were no glomerular intracapillary hypercellularity, mesangial expansion, or crescents seen in any of the kidney sections examined. No significant tubular calcium deposits were seen either. Vascular changes included slightly increased fibrous intimal thickening in 5/6-nephrectomy animals.

Figure 3.

Morphologic findings in the kidneys obtained from experimental animals treated with brodifacoum are similar to those in patients with WRN. (A) Control and (B) 5/6-nephrectomy (ablative nephropathy, 8 weeks postsurgery) rats were treated with brodifacoum. The kidneys were obtained on day 4 post-treatment. The morphologic findings in control rats treated with brodifacoum were mild and nonspecific. In contrast, 5/6-nephrectomy animals had RBCs in Bowman's space and RBC casts in the corresponding tubules. (C) For comparison, the morphologic findings in a kidney biopsy from a patient with WRN are shown. Numerous RBCs and RBC occlusive casts were noticed in tubules and in Bowman's space. Magnification, 200×. Hematoxylin and eosin stain.

No changes in proteinuria were associated with brodifacoum treatment in either experimental group (data not shown).

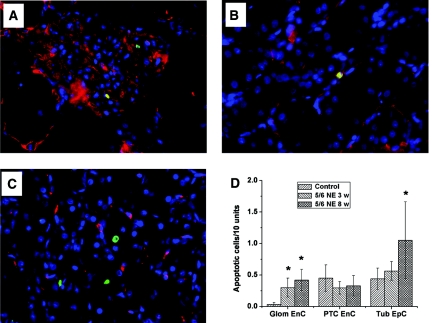

Treatment with Brodifacoum Results in Increased Apoptosis of Endothelial Cells in the Kidney

To investigate possible targets of WRN beyond those described in Table 1, we analyzed apoptosis in different kidney compartments. We found that in control or 5/6-nephrectomy animals not treated with brodifacoum, the number of apoptotic cells was negligible in all kidney compartments. In contrast, treatment with brodifacoum resulted in an increased number of apoptotic cells in control and 5/6-nephrectomy animals. Glomeruli in control rats treated with brodifacoum showed only a few apoptotic endothelial cells (Figure 4D). However, the number of apoptotic cells increased in glomeruli and tubules in 5/6-nephrectomy rats treated with brodifacoum 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery. Thus, the number of apoptotic endothelial cells in glomeruli in 5/6-nephrectomy rats treated with brodifacoum at 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery was significantly higher than in control rats. The number of apoptotic endothelial cells in peritubular capillaries after brodifacoum treatment was similar in control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats. However, brodifacoum treatment 8 weeks after the ablative surgery resulted in a significant increase in the number of apoptotic epithelial cells in the tubules in 5/6-nephrectomy rats (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Animals with WRN have an increased number of apoptotic cells in the kidney. Kidneys were obtained from animals treated with brodifacoum (only 5/6-nephrectomy rats are shown) and were stained with antibodies against CD31 (red), with the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling enzymatic labeling assay (green) and Hoechst (blue). Apoptotic cells were detected in (A) glomeruli, (B) peritubular capillaries, and (C) tubules. Magnification, ×400. (D) The number of apoptotic cells was counted in different compartments of the kidney and by their origin. Treatment with brodifacoum resulted in an increased number of apoptotic endothelial cells in glomeruli (Glom EnC) and tubular epithelial cells (Tub EpC) in 5/6-nephrectomy rats 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (5/6 NE 3 w [n = 8]; and 5/6 NE 8 w [n = 10], respectively), but not in controls (n = 9). No significant changes in the number of apoptotic endothelial cells in peritubular capillaries (PTC EnC) were noted between different experimental groups. *P < 0.05 as compared with control.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence that the WRN reported in humans is reproducible in an animal model. Here we show that excessive anticoagulation by brodifacoum in 5/6-nephrectomy rats reproduces WRN, as documented by increased SC levels, glomerular hematuria, occlusive RBC casts, and acute tubular injury. These findings closely resemble the findings in kidney biopsies from patients with WRN.1 In contrast, treatment with brodifacoum did not affect renal function in control animals, which confirmed our previous observation that to develop WRN an underlying kidney condition should be present.1–3 It appears that AKI develops shortly after the INR increase because in our study the PT was increased more that 10-fold from baseline by day 3, and the elevation in SC levels in 5/6-nephrectomy animals occurred by day 4. However, the PT time increase occurred very rapidly in animals treated with brodifacoum, and it is possible that deterioration of renal function is developing more gradually. Indeed, in 5/6-nephrectomy animals treated with warfarin, SC changes were correlated with changes in PT time, but the PT time increase occurred within several days after the beginning of treatment. Of note, SC changes were not associated with PT increase in control animals with warfarin or brodifacoum treatment. The possibility that the increase in SC is related to hemodynamic changes after treatment with brodifacoum exists but is unlikely because 5/6-nephrectomy and control animals experienced the same amount of bleeding and SC was significantly increased in 5/6-nephrectomy animals only. Moreover, the increase in SC was also dependent on the progression of CKD because animals treated with brodifacoum at 3 weeks after the ablative surgery had an intermediate increase in SC as compared with animals treated 8 weeks after the ablative surgery and with controls. Also, the morphologic findings in 5/6-nephrectomy animals treated 3 weeks after the ablative surgery included less prominent glomerular hemorrhage, occlusive RBC casts, and acute tubular injury as compared with 5/6-nephrectomy animals treated 8 weeks after the ablative surgery (Table 1). This is consistent with our observations in humans that patients with CKD are at much greater risk of WRN than those without CKD.3 Also, the increase in SC in our animal model of WRN is seen within a few days of the onset of brodifacoum-induced coagulopathy, consistent with our WRN studies in humans.

In our studies of human WRN, we did not find a significant relationship between the degree of INR elevation above normal and the risk of WRN.3 However, in our animal model of WRN we found that in the 5/6-nephrectomy rats treated with brodifacoum 8 weeks after the ablative surgery, there was a significant relationship between the degree of INR elevation and the degree of SC elevation. We suggest that this difference between human WRN and animal WRN can be explained by the much wider range in INR achieved in the animal model.

With regard to the mechanism of AKI in the animal model of WRN, we suggest that the coagulopathy increases glomerular hematuria in the 5/6-nephrectomy rats, which results in the formation of obstructing tubular RBC casts. Although this is probably the dominant mechanism of the AKI, we suggest that there may also be other important mechanisms. For example, warfarin has been shown to affect glomerular mesangial cells by interfering with the activation of the product of growth arrest-specific gene 6. This could affect glomerular hemodynamics or aggravate the underlying glomerular disease.7,8 However, we did not find significant differences in growth arrest-specific gene 6 expression in the kidneys obtained from animals treated with brodifacoum and control (data not shown). However, we did find that excessive anticoagulation results in an increased number of apoptotic cells in the kidney of endothelial and nonendothelial origin, especially in the glomeruli. Thus, apoptosis of glomerular cells may also contribute to the pathogenesis of WRN. We also suggest that warfarin-related endothelial damage may play a role in the acute increase in mortality in human WRN.3

In conclusion, we are entering the terra incognita of a previously unrecognized kidney condition. At this moment, very little is known about the pathogenesis of WRN and therapeutic approaches. Nevertheless, we had demonstrated that this is not an uncommon disease, involving at least 30% of CKD patients on warfarin therapy who experienced excessive anticoagulation with INR > 3.0. These patients also have an increased mortality rate. The need of an animal model to better understand the pathogenic mechanisms of WRN is obvious. We suggest that the work presented here is an important step forward in that regard.

CONCISE METHODS

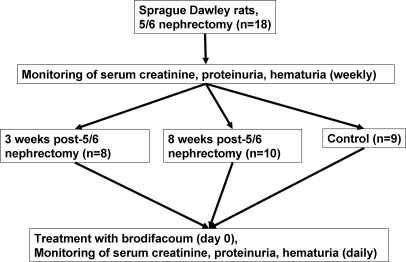

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.9 Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 140 to 160 g were allowed food and water ad libitum. The 5/6-nephrectomy was performed under a ketamine/xylazine (6.0 mg/0.77 mg/100 g) anesthesia by a nephrectomy of the right kidney and resection of two-thirds of the left kidney, as described previously.10–12 Weekly monitoring of SC, proteinuria, and hematuria (by DiaScreen [Chronimed, Inc., Minnetonka, MN] dipstick) was performed. Brodifacoum was given in pellets at 3 (n = 8) or 8 (n = 10) weeks after the ablative surgery, according to the manufacturer protocol. Briefly, animals had free access to brodifacoum-containing pellets at day 0 for 24 hours, which was given instead of regular rodent food. Animals of the same age and gender were used as control (n = 9) and received the same treatment with brodifacoum (Figure 5). For dose-response studies, warfarin was given to control and 5/6-nephrectomy rats 8 weeks after the ablative surgery in drinking water. The amount of warfarin consumed by the animals was measured daily. Several doses of warfarin (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg per day) were used. After the brodifacoum or warfarin administration, monitoring of the PT, SC, proteinuria, and hematuria was performed.

Figure 5.

Experimental protocol of the study. Two- to-3 month-old Sprague–Dawley rats were subjected to 5/6-nephrectomy (ablative nephropathy). SC, proteinuria, and hematuria were measured weekly after the ablative surgery. Animals were treated with brodifacoum (superwarfarin) 3 and 8 weeks after the ablative surgery. SC, proteinuria, and hematuria were measured daily after the treatment. All animals died by day 4 after the treatment with brodifacoum was initiated.

SC was measured using a creatinine reagent assay (Raichem, San Marcos, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The detection method is based on the Jaffe reaction. Briefly, serum was mixed with working reagent at 37°C at a ratio of 1:10 in a 96-well plate and the absorbance was read at 510 nm at 40 and 100 seconds using a Bio-Tek PowerWave 340 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

PT was measured using an Electra 750 coagulation analyzer (Medical Laboratory Automation, Pleasantville, NY) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, blood was collected from the tail vein in an Eppendorf tube with 3.8% sodium citrate as the anticoagulant at a ratio of 9 parts blood to 1 part anticoagulant. The blood specimen is then centrifuged at 1000 RCF for 15 minutes. Thromboplastin is then reconstituted as the manufacturer recommends and warmed on the MLA Electra 750 before use for 15 minutes. Then 0.1 ml of plasma is transferred to the bottom of a cuvette and placed in the incubation station for 3 minutes. The sample is then transferred to the test station. Warm thromboplastin (0.2 ml) is aspirated and placed over the test station. The pipette plunger is pushed down as the test is started. When the timer stops, clotting time is recorded.

Hematuria and proteinuria were measured using DiaScreen (Chronimed, Inc., Minnetonka, MN) reagent strips in the urine. Hematuria was graded using a semiquantitative scale of 0 to 3+. Score 0 was designated for negative hematuria, score 1+ for mild hematuria, score 2+ for moderate hematuria, and score 3+ for large hematuria.

Kidneys were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut as 3-μm sections. Hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were analyzed by two independent pathologists who were not aware of the source of the kidney sections. In each animal an entire area of longitudinal sections of one kidney was evaluated. In 5/6-nephrectomy animals, the scarred areas related to the surgical procedure were excluded. In general, each section contained >50 glomeruli, >500 tubules, and >10 small arteries.

Interobserver agreement was calculated based on kappa statistics.13 Rates were categorical from 0 to 3 with 0.5 steps.

- Agreement: 90.38%

- Expected agreement: 65.69%

- Kappa: 0.7197

- SEM: 0.0397

- Z: 18.15

- Prob > Z: 0.0000

The results show an almost perfect agreement between the two observers (90.38%) with a highly significant P value (P < 0.0001).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM if not otherwise specified. Differences between groups were analyzed by the two-paired t test or ANOVA test where it was applicable. Tukey post test was performed to analyze the differences between groups in conjunction with ANOVA. Association between SC changes and PT time increase was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis with a two-tailed P value. Kappa statistics13 were used to study the interobserver agreement.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in a part by a start-up fund for S.V.B. provided by the Department of Pathology at The Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brodsky SV, Satoskar A, Chen J, Nadasdy G, Eagen JW, Hamirani M, Hebert L, Calomeni E, Nadasdy T: Acute kidney injury during warfarin therapy associated with obstructive tubular red blood cell casts: A report of 9 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 1121–1126, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brodsky SV, Collins M, Park E, Rovin BH, Satoskar AA, Nadasdy G, Wu H, Bhatt U, Nadasdy T, Hebert LA: Warfarin therapy that results in an international normalization ratio above the therapeutic range is associated with accelerated progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract 115: c142–c146, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brodsky SV, Nadasdy T, Rovin BH, Satoskar AA, Nadasdy G, Wu HM, Bhatt U, Hebert LA. Evidence that warfarin related nephropathy occurs commonly in both those with and without chronic kidney disease and is associated with increased mortality rate. 2011 Kidney Int, 2011, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao YG, Liu XQ, Chen YC, Hao K, Wang GJ: Warfarin maintenance dose adjustment with indirect pharmacodynamic model in rats. Eur J Pharm Sci 30: 175–180, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chun MJ, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in nephrotic adults: Presentation, prognosis, and response to therapy of the histologic variants. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2169–2177, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas DB, Franceschini N, Hogan SL, Ten Holder S, Jennette CE, Falk RJ, Jennette JC: Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants. Kidney Int 69: 920–926, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yanagita M, Ishii K, Ozaki H, Arai H, Nakano T, Ohashi K, Mizuno K, Kita T, Doi T: Mechanism of inhibitory effect of warfarin on mesangial cell proliferation. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2503–2509, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yanagita M: Gas6, warfarin, and kidney diseases. Clin Exp Nephrol 8: 304–309, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subject: Revision of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Bethesda, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Services, National Institutes of Health, Publication Number 86-23, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 10. El Nahas AM, Bassett AH, Cope GH, Le Carpentier JE: Role of growth hormone in the development of experimental renal scarring. Kidney Int 40: 29–34, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Ouyang J, Ellis V, Churchill M, Churchill PC: Role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in hemodynamic adaptations after graded renal mass reduction. Am J Physiol 264(6 Pt 2): R1254–R1259, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin KA, Picken M, Bidani AK: Method of renal mass reduction is a critical modulator of subsequent hypertension and glomerular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 2023–2031, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen J: A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Ed Psych Measure 20: 37–46, 1960 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y, et al. : The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 55: 713–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]