Abstract

Objective:

Several lines of evidence suggest that pathologic changes underlying Alzheimer disease (AD) begin years prior to the clinical expression of the disease, underscoring the need for studies of cognitively healthy adults to capture these early changes. The overall goal of the current study was to map the cortical distribution of β-amyloid (Aβ) in a healthy adult lifespan sample (aged 30–89), and to assess the relationship between elevated amyloid and cognitive performance across multiple domains.

Methods:

A total of 137 well-screened and cognitively normal adults underwent Aβ PET imaging with radiotracer 18F-florbetapir. Aβ load was estimated from 8 cortical regions. Participants were genotyped for APOE and tested for processing speed, working memory, fluid reasoning, episodic memory, and verbal ability.

Results:

Aβ deposition is distributed differentially across the cortex and progresses at varying rates with age across cortical brain regions. A subset of cognitively normal adults aged 60 and over show markedly elevated deposition, and also had a higher rate of APOE ϵ4 (38%) than nonelevated adults (19%). Aβ burden was linked to poorer cognitive performance on measures of processing speed, working memory, and reasoning.

Conclusions:

Even in a highly selected lifespan sample of adults, Aβ deposition is apparent in some adults and is influenced by APOE status. Greater amyloid burden was related to deleterious effects on cognition, suggesting that subtle cognitive changes accrue as amyloid progresses.

Beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein deposition in the human brain is a marker of Alzheimer disease (AD) and a key component in current theories of the disease's pathogenesis.1 At least 20% of cognitively normal elderly evidence Aβ neuropathology upon autopsy.2,3 The pathologic changes underlying AD begin decades prior to its clinical expression,4 underscoring the need for normal aging studies to capture these early changes.5

Aβ deposition may begin earliest in the precuneus,6 and frontal, cingulate, and parietal regions are primary areas of Aβ deposition.7 Although the etiology of Aβ deposition is poorly understood, the APOE ϵ4 allele is a significant risk factor for elevated amyloid8–12 and AD diagnosis.13

Research on the impact of Aβ on cognition in normal adults is inconsistent.5 Most studies reported nonsignificant associations with memory,6,10,14–17 yet some show modest correlations of Aβ to decreased memory scores18,19 with the strongest effects observed in difficult memory tasks20 or on longitudinal change in memory.11,21 Studies investigating the impact of Aβ on nonmemory domains consistently report nonsignificant results.6,14,16,17,19 The extant literature, however, is limited by small, restricted samples of adults aged 60 or older.

A recent attempt to define preclinical stages of AD suggests this phase includes no measurable cognitive change.22 However, few studies of healthy adults, especially middle-aged and younger adults, exist to verify this statement. Thus, the overall goals of the current study were 1) to map the cortical distribution of Aβ in a healthy sample aged 30–89 and 2) to determine how Aβ burden affects cognitive function in apparently healthy, high-functioning individuals.

METHODS

Participants.

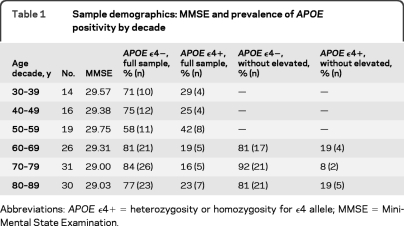

Participants were recruited from the Dallas Lifespan Brain Study (DLBS; n = 350, age 20–89), a comprehensive study on cognitive function and neuroimaging. DLBS volunteers are recruited from the community and screened against neurologic and psychiatric disorders, loss of consciousness >10 minutes, drug/alcohol abuse, and major heart surgery or chemotherapy within 5 years. Participants are native English speakers and right-handed. DLBS participants 30–89 years old who completed testing within the last 12 months (n = 215) were invited to return for an Aβ PET scan. Replies numbered 196 (91%) and of those, 90% accepted invitation (177). The resulting sample (table 1) consisted of the first 137 participants scanned (82 women; 55 men), aged 30–89 (mean age 64 ± 16.3 years). Participants were well-educated (mean 16.4 ± 2.7 years) and scored highly (29.3 ± 0.9) on the Mini-Mental State Examination.23 Mean delay between initial testing in the DLBS and the PET imaging session was 6.9 ± 4.02 months.

Table 1.

Sample demographics: MMSE and prevalence of APOE positivity by decade

Abbreviations: APOE ϵ4+=heterozygosity or homozygosity for ϵ4 allele; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination.

Procedures.

All participants completed 4 2-hour visits: 2 for cognitive and neuropsychological testing, followed by 1 for MRI scanning, and 1 for Aβ imaging.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent.

This study was approved by the University of Texas at Dallas and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center human investigations committees. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment and were debriefed in accord with university human investigations committee guidelines.

APOE genotyping.

Venous blood was collected into EDTA-anticoagulated tubes and genomic DNA was isolated by standard protocols.24 Typically 50–70 μg of DNA were isolated from 2 mL of whole blood. APOE genotypes were determined by real-time PCR using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA) unique for each APOE single nucleotide polymorphism, rs429358 (assay ID C3084793 20) and rs7412 (assay ID C 904973 10), according to established protocols.25 APOE data were available for all but one participant, and participants were classified as APOE ϵ4 carriers if they had at least one ϵ4 allele.

Neuropsychological battery.

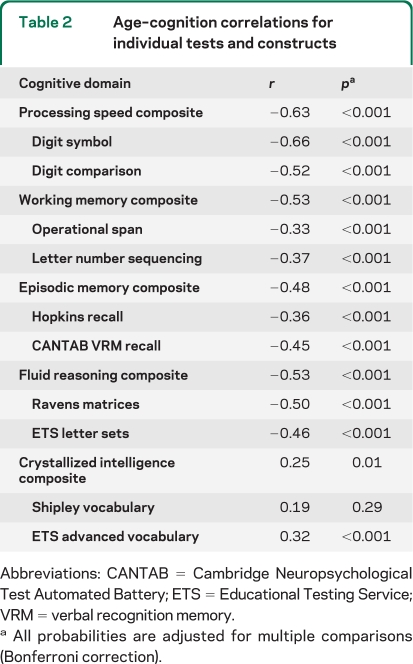

Participants completed 2 tests each of processing speed, working memory, episodic memory, crystallized abilities, and fluid reasoning. Processing speed, an index of speed of cognitive operations, was measured by Digit Comparison26 and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)–III Digit Symbol.27 Working memory describes the ability to hold and manipulate information simultaneously across a short period of time and was measured by Operation Span28 and WAIS-III Letter-Number Sequencing.27 Episodic memory assesses the ability to recall information over time and was measured with 2 word-list memory tasks: the Hopkins Verbal Learning Task29 and Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) Verbal Recognition.30 Crystallized abilities describe world knowledge acquired with age (e.g., verbal ability) and was measured with the Educational Testing Service (ETS) Advanced Vocabulary Scale31 and Shipley Vocabulary Scale.32 Fluid reasoning is the ability to discover and apply rules of sets or situations and was measured by ETS Letter Sets31 and Raven's Progressive Matrices.33 Each of the 2 tests was standardized to z scores and averaged to form composite indices for each of the 5 cognitive constructs (see table 2for age–cognition correlations).

Table 2.

Age–cognition correlations for individual tests and constructs

Abbreviations: CANTAB=Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery; ETS=Educational Testing Service; VRM=verbal recognition memory.

All probabilities are adjusted for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction).

PET protocol.

PET acquisition.

Participants were injected with a 10-mCi bolus of 18F-florbetapir for a 10-minute emission and 10-minute transmission scan. At 30 minutes postinjection, participants were positioned on the imaging table of a Siemens ECAT HR PET scanner. Velcro straps and foam wedges secured the participant's head and the participant was positioned using laser guides. A 2-minute scout was acquired to ensure the brain was completely in the field of view and there was no rotation in either plane. A 2-frame by 5 minutes each dynamic emission acquisition began 50 minutes postinjection and immediately after an internal rod source transmission scan was acquired for 7 minutes. The transmission image was reconstructed using backprojection and a 6-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter. Emission images were processed by iterative reconstruction, 4 iterations and 16 subsets with a 3-mm FWHM ramp filter.

PET data processing.

Each participant's PET scan was spatially normalized to a florbetapir uptake template34 (2 × 2 × 2 mm3 voxels) using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) and in-house MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA) scripts and visually inspected for registration quality. We created 8 bilateral regions of interest (ROIs) and a cerebellar hemisphere reference region (excluding peduncles) by modifying AAL masks (figure e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org). We computed standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR) for each ROI by normalizing to mean cerebellar uptake. To minimize inclusion of nonspecific white matter binding in our ROIs, we identified the gray/white matter boundary threshold in the PET images (SUVR = 1.2) in our youngest subjects (age <35, n = 9), and eroded each ROI by the resulting binarized white matter mask.

RESULTS

Effect of age on mean cortical uptake.

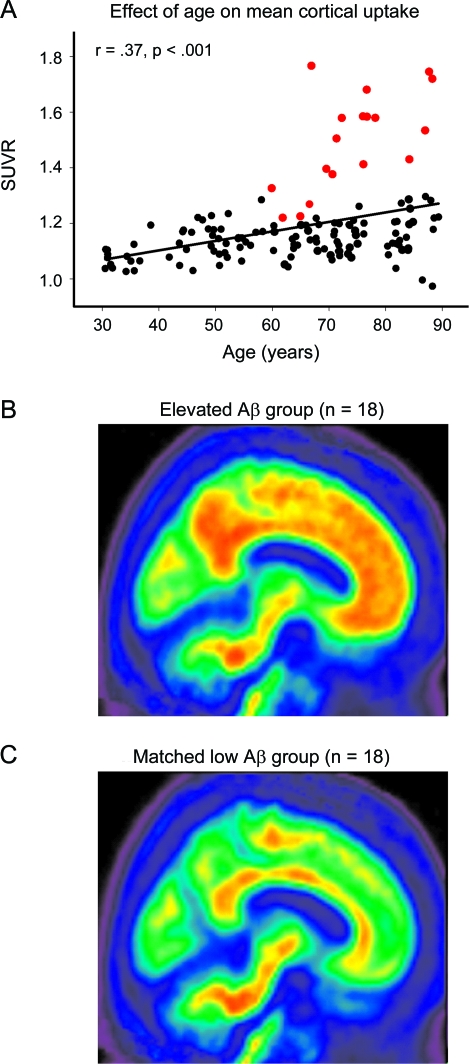

Mean SUVR averaged across regions was analyzed with a general linear model (GLM) using age and sex as predictors. We observed a significant main effect of age (F1,133 = 25.14, p < 0.001) due to a linear increase in amyloid with age. Neither the effect of sex (F1,133 = 1.94, p = 0.17), nor age × sex (F1,133 = 3.22, p = 0.08), reached significance, nor did the quadratic component of age (F < 1, p = NS). We identified an elevated Aβ subgroup of individuals >60 years who exceeded the 95% confidence interval from the regression of age on mean SUVR (n = 18; figure 1A). The resulting cutoff value was a mean SUVR of 1.22 with a mean value of 1.50 ± 0.17. Individuals with elevated amyloid represented 20.4% of the older adult sample (≥60 years). The mean uptake for the elevated Aβ subgroup (figure 1B) is shown in comparison to a group of age- and sex-matched participants without elevated burden (figure 1C).

Figure 1. Age effects on β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition.

(A) The effect of age on mean cortical uptake across the lifespan. Mean Aβ burden increases linearly from age 30 to 89 in healthy adults. The subgroup of individuals displayed in red showed elevated Aβ outside the 95% confidence interval of the sample. (B) Mean standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) image of the elevated Aβ subgroup (n = 18, denoted in red in A). For comparison, (C) illustrates mean SUVR image in a group of 18 age- and sex-matched individuals with lower levels of amyloid.

Effect of age on regional uptake.

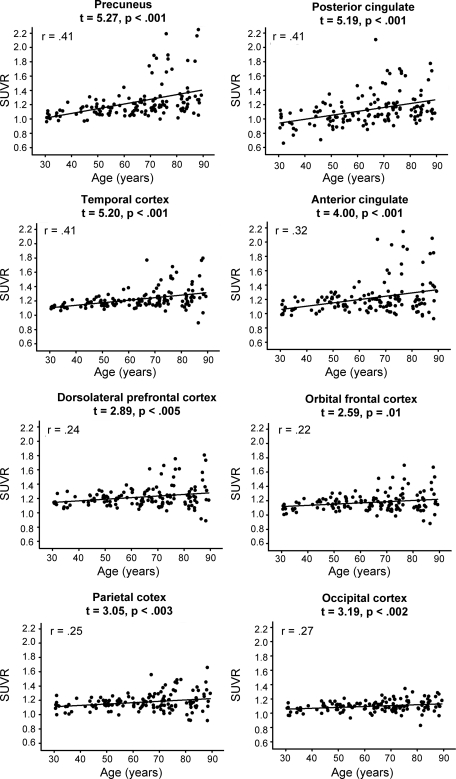

We examined differences in SUVRs across the 8 regions (figure e-1), utilizing age and sex as predictors in a GLM treating region as a repeated measure. There was a significant main effect of age (F1,133 = 25.14, p < 0.001) due to increases in amyloid with greater age. Additionally, a significant within-subjects effect of ROI (F7,931 = 34.76, p < 0.001) and age × ROI interaction (F7,931 = 14.62, p < 0.001) occurred. The age gradient for amyloid deposition varied as a function of region. Specifically, the precuneus, temporal cortex, and anterior and posterior cingulate showed the greatest increases with age (figure 2) with less pronounced age-related increases in the dorsolateral prefrontal (DLPFC) and orbital-frontal (OFC), parietal, and occipital cortices.

Figure 2. Regional increases in β-amyloid deposition across the lifespan.

The anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, precuneus, and temporal cortices evidence the steepest increases in amyloid with age. Occipital, parietal, and prefrontal cortices evidence a shallower increase in amyloid deposition across the age range. SUVR = standardized uptake value ratio.

Removal of elevated Aβ subgroup.

To assess the impact of the elevated Aβ subgroup on age trends, we repeated the analysis, excluding the elevated Aβ subgroup. We again observed an age effect, with a linear increase in mean amyloid burden over the lifespan, F1,116 = 15.17, p < 0.001. When we further restricted the analysis to those >60 years (the age group typically included in other studies) the age effect was mitigated to a trend (p = 0.08).

Effect of APOE genotype on amyloid deposition.

Our sample contained 24% ϵ4 carriers, matching the general population. Prevalence varied, however, by decade (table 1). The younger half of the sample (ages 30–59 years) had a higher frequency of ϵ4 carriers (33%) than those over age 60 (19.5%). Interestingly, 38% of elevated Aβ participants are ϵ4 carriers, more than double the prevalence in the remaining older participants (15%, n = 70).

To directly test the effect of APOE ϵ4 on Aβ burden we ran GLM analyses with age, sex, APOE status, and their associated interaction terms as predictors of mean cortical uptake. A significant main effect of APOE ϵ4 was found (F1,131 = 4.35, p = 0.04): ϵ4 carriers had a higher mean SUVR (1.22 ± 0.18) than non-ϵ4 carriers (1.17 ± 0.14). The APOE × age interaction was nonsignificant, p = 0.14. To test APOE effects on regional uptake, a repeated-measures GLM was run with the 8 cortical ROIs as a repeated-measures dependent variable. Results revealed a significant main effect of APOE (F1,131 = 4.35, p = 0.04) and an APOE × ROI interaction (F7,917 = 2.37, p = 0.02). Post hoc univariate regressions found significant effects of APOE ϵ4 on anterior cingulate (F1,131 = 6.72, p = 0.01), temporal (F1,131 = 4.63, p = 0.03), and OFC (F1,131 = 5.38, p = 0.02). A trend in the DLPFC was also detected (F1,131 = 3.56, p = 0.06). The remaining 4 cortical regions showed no significant effects, all ps = NS (table e-1).

Effect of Aβ on cognitive performance.

Utilizing a GLM on the full sample, we assessed the effects of age and Aβ (controlling for sex) and their interaction on the standardized composite measures of 5 domains of cognition: processing speed, working memory, episodic memory, fluid reasoning, and crystallized intelligence. There was a significant dose–response effect of mean cortical Aβ on processing speed (F1,133 = 4.13, p = 0.04) and fluid reasoning (F1,132 = 3.98, p < 0.05), such that poorer performance on these measures was observed as amyloid burden increased. No significant effects were found for working memory (F1,133 = 1.94, p = 0.17), episodic memory (F < 1, p = NS), or crystallized intelligence (F < 1, p = NS) in the full lifespan sample.

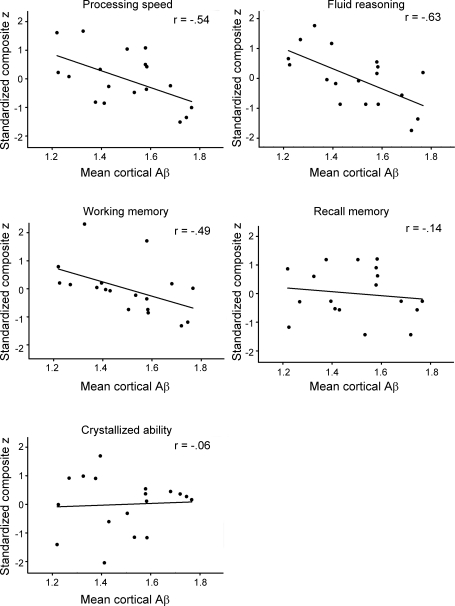

Additionally, we ran correlational analyses on the elevated Aβ subgroup, and the full sample without the elevated Aβ subgroup. In the elevated Aβ subgroup (n = 18), there was a significant association of increasing amyloid burden to decreasing cognitive performance for processing speed (r = −0.55, p < 0.02), working memory (r = −0.46, p = 0.05), and reasoning ability (r = −0.59, p = 0.01), but no significant association with episodic memory (r = −0.09, p = NS) or crystallized intelligence (r = 0.05, p = NS) was found (figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of elevated β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition on 5 domains of cognition.

Processing speed, working memory, and fluid reasoning are significantly reduced with increasing Aβ burden, whereas crystallized ability and episodic memory were unaffected.

In the full sample without the elevated Aβ subgroup (n = 119), we found a significant effect of amyloid burden only on reasoning (F1,115 = 6.44, p = 0.01), with increasing amyloid related to poorer performance.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we report on a large-scale lifespan study (ages 30–89) of amyloid deposition using 18F-florbetapir in healthy adults. We demonstrate that even in a highly selected lifespan sample of healthy aging, Aβ deposition increases with age and is particularly elevated in about 20% of adults aged 60 and over. Moreover, Aβ load is distributed differentially across the cortex. Our cross-sectional results suggest deposition progresses most rapidly in the precuneus, temporal cortex, posterior and anterior cingulate, respectively. In contrast, the occipital and parietal cortices, as well as DLPFC, and OFC showed small to moderate age effects. In the elevated Aβ subgroup, there was a much greater prevalence of ϵ4 carriers (38%) compared to the older adults without elevated Aβ (15%). Importantly, high-amyloid adults showed poorer cognitive function as demonstrated on measures of processing speed, working memory, and fluid reasoning, and the magnitude of difference was related to the amount of amyloid deposited.

Removal of the elevated Aβ subgroup did not diminish the positive relationship of aging to amyloid burden, thus yielding evidence for a linear increase in amyloid, even in a sample with lower levels of Aβ, across the entire age span tested (30–89). The pattern of findings also suggests amyloid deposition from age 30–59 increases measurably, although only longitudinal data will establish the clinical importance of subtle increases in middle age. Additionally, these data show many healthy adults even in their 80s had relatively modest levels of amyloid. We note that a significant number of 70- to 89-year-olds in the general population would not meet the physical or cognitive criteria for admission to this study, and thus might be more likely to have elevated Aβ. Therefore, the fraction of low-amyloid adults observed in our healthy aging study is likely greater than in the general population.

The in vivo data we present here are in accord with the postmortem literature, which shows a steady increase in Aβ plaque deposition across the age span of 26–95 years.35 Further, postmortem reports of a slowing of the age-related increase in plaques at the older end of the lifespan36 are consistent with our finding of only subtle age-related increases in amyloid in those >60 years without elevated Aβ.

APOE ϵ4 in our study had the expected effect of increasing risk for elevated Aβ. We observed a rate of 24% ϵ4 positivity, matching population estimates.37 Across the whole sample, APOE ϵ4 was associated with greater regional amyloid burden in the anterior cingulate, temporal lobes, and prefrontal cortex, consistent with other reports.8–10,38 As we expected, 30- to 59-year-olds had a higher likelihood of carrying the APOE ϵ4 allele than individuals over 60, as many ϵ4 carriers over 60 might have converted to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD and not been admitted to our study. Moreover, the elevated Aβ subgroup had more than double the prevalence of APOE ϵ4 than the remaining older adults, highlighting the risk conferred by this genotype.

Perhaps one of the most important questions is whether increased Aβ in normal adults has detectable cognitive consequences, particularly in light of the introduction of a potential preclinical phase of the disease, which is defined by the presence of amyloid in the absence of cognitive dysfunction.22 We found in the full sample dose–response association with poorer performance on processing speed and fluid reasoning. Additionally, in high amyloid participants, the magnitude of amyloid burden was related to deficits in processing speed, fluid reasoning, and working memory. These are also the domains demonstrating the most age-related declines in healthy aging.

We did not find an association between Aβ and episodic memory performance, in agreement with previous studies,6,7,14–17,39,40 although some amyloid associations with memory performance have been reported.18,19 One possible explanation for the lack of association with episodic memory is that amyloid-related cognitive deficits may preferentially occur on tasks demonstrating the most age-related decline. In our sample, episodic memory was less affected by age than other domains. Thus, a memory–amyloid association may only be observed on more demanding memory tasks20 than those included in our study. Additionally, amyloid accumulation may be more sensitive to an individual's longitudinal decline in memory over time11,21 than to cross-sectional age estimates.

Investigations of cognitive domains outside the realm of memory have yielded nonsignificant findings.6,14,16,17,19 In fact, one study that examined Aβ effects on memory, working memory, and crystallized intelligence in 32 normal adults with a mean age of 71.6 ± 6.6 years reported an amyloid correlation with memory but not other cognitive domains.19 One reason for this discrepancy could be the larger sample size and extended age range in the present study. Examining a much younger population than previous studies may have allowed us to detect differences in cognitive performance due to Aβ burden that may be apparent earlier on in the aging process, particularly in a predominantly healthy sample.

One potential limitation of the study is the correspondence of florbetapir uptake to plaque burden in individuals with lower levels of amyloid than observed in MCI or AD populations. However, we examined data from a study34 combining postmortem tissue staining and antemortem florbetapir imaging and found that SUVR levels below 1.22 significantly correlated with immunohistochemistry (r = 0.71, p < 0.001). Our cognitive findings further confirm the detrimental effects of gray matter plaque are detectable even at these lower SUVR values. When the elevated Aβ subgroup is removed, the effect of cortical uptake on reasoning remains significant. Finally, while nonspecific uptake (as measured in the centrum semiovale) increases with age, it does not correlate with any of the measured cognitive domains. These results taken together suggest increasing neocortical florbetapir uptake even at lower levels is associated with reduced cognitive performance, and is specific to gray matter plaque burden.

Our results indicate that cognitive declines across many domains are linked to Aβ in adults who have apparently good cognitive health, suggesting detectable cognitive effects may occur even in the recently proposed preclinical phase of AD. It is important to note, however, that the relative contribution of amyloid vs other well-demonstrated predictors of cognitive aging (e.g., regional atrophy, leukoaraiosis) is unclear. Studies directly addressing which neural processes and insults are most predictive of cognitive decline are needed. Furthermore, the long-term consequences of Aβ deposition in cognitively normal adults can only be addressed with a longitudinal design. Longitudinal follow-up, which is planned for the DLBS, will help determine whether Aβ deposition increases in those who are already elevated and at what rate low amyloid adults increase Aβ burden. A key question for future research is whether some adults will maintain cognitive health for a sustained period and whether elevated Aβ deposition in healthy adults always predetermines a declining cognitive trajectory.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by NIH grants 5R37AG-006265-25, 3R37AG-006265-25S1, and P30 AG12300, and Alzheimer's Association grant IIRG-09-135087. K.M.R. was supported in part by NIA grant 1K99-AG-036848-1. The radiotracer was provided to the study by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. The authors thank Michael Viguet for assistance with PET scanning, Chris Paliotta for collecting blood samples, and Gérard N. Bischof, Prasanna Tamil, and Erin Wooden for participant testing and scheduling.

GLOSSARY

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- DLBS

Dallas Lifespan Brain Study

- DLPFC

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- ETS

Educational Testing Service

- FWHM

full width at half maximum

- GLM

general linear model

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- OFC

orbital-frontal cortex

- ROI

region of interest

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

- WAIS

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Rodrigue drafted the manuscript and statistically analyzed the data presented. Drs. Rodrigue, Kennedy, Devous, and Park were responsible for study concept, design, and interpretation of the results. J.R. Rieck collected cognitive and PET imaging data. Dr. Diaz-Arrastia supervised the DNA extraction and performed APOE genotyping. Dr. Mathews supervised PET acquisition. Drs. Rodrigue, Kennedy, and Devous and A.C. Hebrank visually inspected PET scans and performed all PET data processing. All authors edited the manuscript for intellectual content. Drs. Rodrigue, Kennedy, and Park were responsible for overall study supervision and coordination.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Rodrigue receives research support from the NIH/NIA. Dr. Kennedy receives research support from the NIH/NIA. Dr. Devous served as an Associate Editor for Journal of Experimental Biology; serves on a scientific advisory board for Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc.; serves as a consultant for Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc. and Bayer Schering Pharma; receives research support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc., the NIH (NIA, NIDRR, NIDA), the US Department of Education, and the Alzheimer's Association; and holds stock in Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc. A.C. Hebrank and J.R. Rieck report no disclosures. Dr. Diaz-Arrastia serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Neurotrauma and receives research support from the NIH/NIDRR and the Alzheimer's Association. Dr. Mathews reports no disclosures. Dr. Park receives research support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc., the NIH/NIA, and the Alzheimer's Association; and her son litigated on behalf of Pfizer Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 2002;297:353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer's disease Ann Neurol 1999;45:358–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett D, Schneider J, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology 2006;66:1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jack CR, Jr., Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, et al. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2009;132:1355–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Park DC. Beta-amyloid deposition and the aging brain. Neuropsychol Rev 2009;19:436–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006;67:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jack CR, Jr., Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, et al. 11C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer's disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain 2008;131:665–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 2010;67:122–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:6820–6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging 2010;31:1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Storandt M, Mintun MA, Head D, Morris JC. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Abeta deposition. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1476–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villemagne V, Pike K, Darby D, et al. A [beta] deposits in older non-demented individuals with cognitive decline are indicative of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia 2008;46:1688–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 1993;261:921–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bourgeat P, Chetelat G, Villemagne VL, et al. Beta-amyloid burden in the temporal neocortex is related to hippocampal atrophy in elderly subjects without dementia. Neurology 2010;74:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedden T, Van Dijk KR, Becker JA, et al. Disruption of functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. J Neurosci 2009;29:12686–12694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oh H, Mormino EC, Madison C, Hayenga A, Smiljic A, Jagust WJ. β-Amyloid affects frontal and posterior brain networks in normal aging. Neuroimage 2011;54:1887–1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mormino EC, Kluth JT, Madison CM, et al. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain 2009;132:1310–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, et al. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2007;130:2837–2844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rentz DM, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, et al. Cognition, reserve, and amyloid deposition in normal aging. Ann Neurol 2010;67:353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Resnick SM, Sojkova J, Zhou Y, et al. Longitudinal cognitive decline is associated with fibrillar amyloid-beta measured by [11C]PiB. Neurology 2010;74:807–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:280–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller S, Dykes D, Polesky H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988;16:1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koch W, Ehrenhaft A, Griesser K, et al. TaqMan systems for genotyping of disease-related polymorphisms present in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:1123–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salthouse T, Babcock R. Decomposing adult age-differences in working memory. Dev Psychol 1991;27:763–776 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III (WAIS-III). New York: Psychological Corporation; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turner M, Engler R. Is working memory capacity task dependent? J Memory Lang 1989;28:127–154 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin Neuropsychol 1991;5:125–142 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robbins T, James M, Owen A, Sahakian B, McInnes L, Rabbitt P. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): a factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1994;5:266–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ekstrom R, French J, Harman H, Dermen D. Manual for Kit of Factor Referenced Cognitive Tests. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service: 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zachary RA, Shipley WC. Shipley Institute of Living Scale: Revised Manual. Western Psychological Services; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raven JC. Standard Progressive Matrices: Sets A, B, C, D & E. Oxford: Oxford Psychologists Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, et al. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA 2011;305:275–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging 1997;18:351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr., Buckles VD, et al. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:1026–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science 1988;240:622–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chételat G, Villemagne VL, Pike KE, et al. Larger temporal volume in elderly with high versus low beta-amyloid deposition. Brain 2010;133:3349–3358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rowe CC, Ackerman U, Browne W, et al. Imaging of amyloid beta in Alzheimer's disease with 18F-BAY94–9172, a novel PET tracer: proof of mechanism. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sperling RA, Laviolette PS, O'Keefe K, et al. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron 2009;63:178–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.