Abstract

Hypothesis

Intracochlear visualization is achievable with chip-on-tip endoscopes—also called (digital) video endoscopy, videoscopy, electronic endoscopy or endoscopy with distal chip/sensor/camera technology.

Background

Recent advances in digital camera sensor sizes have significantly reduced the size of chip-on-tip endoscopes to sizes near that of the scala tympani opening up the possibility of intracochlear visualization.

Methods

We compared the image quality of chip-on-tip cameras with commercially-available rigid endoscopes (a.k.a. Hopkins rods) and commercially-available fiber optic scopes (sialendoscopes). Furthermore, we performed a feasibility study to elucidate the spatial constraints which future visualization technology must reach to allow intracochlear visualization.

Results

Image resolution for chip-on-tip endoscopes ranks before fiberscopes and after Hopkins rods. The image quality depends further on illumination which remains unresolved for chip-on-tip endoscopes for intracochlear visualization. The insertion depth of the currently available cameras allows up to 270° travel from the round window.

Conclusion

Visual guidance and inspection inside scala tympani is possible with a novel, small-size, digital-camera endoscope. This may find clinical applicability for visual confirmation of anatomy during cochlear implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Surgeons depend upon visual assessment for successful intraoperative therapy. However, visual guidance has yet to be used for the insertion of cochlear implant electrodes. The goal of this study was to assess current technology regarding possibilities and constraints of visualizing the inside of human cochleae, more specifically the scala tympani. At present there are three potential technologies which could allow intracochlear visualization—rigid endosocpes, fiberscopes, and digital cameras (a.k.a. chip-on-tip endoscopes).

Rigid endoscopes are well known to the otolaryngologist. Most commonly, they are called Hopkins rods in deference to the British physicist who invented them (Harold Horace Hopkins, 1918–1994). These rigid endoscopes are telescopes with the air-containing spaces between the lenses replaced with polished glass rods allowing excellent light transmission and magnification. Rod lenses have superseded traditional lens systems. A further type uses gradient-index (GRIN) rod lenses which have planar end faces and varying refractive index—high at the center line and smaller at the periphery. Since rigid endoscopes allow direct visualization, they offer the best possible view with resolution down to the order of micrometers; this resolution is limited by properties of the lens being used—specifically focal length, refraction limit and lens errors (i.e. aberration: blurring and distortion). Furthermore, rigid endoscopes depend upon camera systems to record interventions. The quality of the camera impacts upon image resolution based upon overall camera chip dimensions, the size of individual photo sensing element on the camera chip, and illumination of the target.

Very few research articles have been published where the scala tympani (ST) is inspected through a cochleostomy or the round window with a rigid endoscope. This could be due to access difficulty or due to the fact that the diameter of most rigid endoscopes is larger than typical cochleostomies. Chole took in-vivo pictures of the human ST with a 1.7 mm rigid endoscope and published one of them on the cover of a department newsletter [1, personal communication].

Monfared et al. showed images from the inside of guinea pigs cochleae to determine the blood flow using one-photon fluorescence microendoscopy [2]. With an experimental setup they demonstrated in-vivo images taken with a rigid 1mm endoscope, which was assembled using GRIN lenses. Beside blood vessels, structures such as the osseous spiral lamina, spiral ligament, basilar membrane, and the curvature of ST were visualized. Ozluoglu and Akbasak described the use of rigid endoscopy during neurectomy to visualize extra-cochlear structures [3]. For deep insertions into ST the most important limitation of such endoscopes is their rigidity limiting analysis past the straight portion of the basal turn of the cochlea.

Fiberscopes consist of bundles of optical fibers with some of the fibers delivering light and others transmitting the reflected light as an image back to the observer. Individual fibers can be as small as several micrometers and image quality is dependent on the number of fibers with low resolution images the norm. The poorer image quality is accepted due to the advantage of flexibility allowing access to curvilinear areas such as the cochlea. While single fibers are highly flexible with bending radii of only a few millimeters, fiberscopes with several thousand fibers and an overall diameter in the millimeter range have bending radii of one centimeter or more. Additionally, fiberscopes have inflexible lens systems at their tips which limits tip mobility. Radius of curvature for the tip of such systems is dependent upon the lens which is dependent upon the desired focal length. For systems used to visualize inside the cochlea, the maximum tolerable radius of curvature is approximately half the diameter of the cochlea, or approximately 5 mm. As such, fiberscopes with good image quality (e.g. 10,000 imaging fibers or more) despite being considered flexible cannot be used to visualize beyond the basal turn.

Balkany and Fradis reported visualization of partially ossified and obstructed cochleae in identifying normal and abnormal structures inside the cochlea with flexible scopes [4, 5]. Kautzky et al. combined this visualization ability with laser ablation of ossified regions [6]. Later studies revealed the possibility of spiral ligament and basilar membrane visualization [7]. Campbell et al. showed similar ability in gerbils and were able to correlate these structures to the CI electrode position [8]. Fritsch gave an overview of multiple fiberscope views of the human inner ear within a temporal bone study showing different entry points into the cochlea (basal, middle, apical turn, oval window), the vestibule, and the semi-circular canal [9].

Digital camera chips, produced as charged coupled devices (CCDs) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductors (CMOSs), consist of a layer of photoactive material (usually silicon) which emits an electric charge proportional to light intensity which can be processed into a visual image. Cameras are commonly used at the end of rod lens or flexible endoscopes allowing documentation and large screen visualization in the operating room or outpatient setting. The usage of chip cameras directly inside the human body started in 1984 with colonoscopy [10] and was further refined by combining this with wireless technology resulting in the capsule endoscopy [11]. Recent developments in semiconductor manufacturing concerning production costs now enable the use of disposable, pre-sterilized cameras in such applications [12, 13].

In the field of laryngology, camera chips have been placed on flexible endoscopes which allow higher resolution images of the upper aerodigestive tract than traditional fiberscopes. Multiple studies have shown the benefit of distal chip cameras when evaluating the vocal folds regarding reflux, nodules, polyps, and dysphonia [14, 15 16]. Over the past several years, chip-on-tip endoscopy has reduced significantly in size—from greater than 3.5 mm to less than 1.5 mm in diameter [17, 18]—which enables exploration of smaller size applications. Chip-on-tip endoscopy has yet to be reported for visualization of intracochlear anatomy. We aim to show spatial restrictions and image comparisons of the three different endoscope types and discuss the potential suitability of chip-on-tip scopes for visual guidance inside ST.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was divided into two different parts. Part I used a scala tympani (ST) phantom from Cochlear Corporation (Sydney, Australia) to explore physical limitations of acquiring images from inside the cochlea. For the second part of the study, two human temporal bones were dissected via mastoidectomy, posterior tympanotomy and cochleostomy; the aim of Part II was to show the image quality of the different endoscopy types. Endoscopes studied and characteristics of each are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the used endoscope types and their characteristics

| Hopkins rod | Fiberscope | Digital camera chip | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used for study | Part I and II | Part I | Part I and II | Part I | Part I and II | Part I |

| Manufacturer and type | Gyrus Acmi explorent 23-5200 | Storz Sial-endoscope 11581 A | Storz Sial-endoscope 11582 A | Storz Sial-endoscope 11583 A | Medigus IntroSpicio™ 120 | AWAIBA NanEye |

| Tip diameter | 1.7mm | 0.89mm | 1.1mm | 1.6mm | 1.2mm | 1.4mm1 |

| Rigid length | complete | several cm | several cm | several cm | 5mm 2 | 1.5mm |

| Picture element quantity [pixel] | several 100,0003 | 6,000 (fibers) | 6,000 (fibers) | 6,000 (fibers) | 49,280 | 62,500 |

| Image capture device | USB camera BigCatch EM-310C (3.2Mpx) | USB camera BigCatch EM-310C (3.2Mpx) | USB camera BigCatch EM-310C (3.2Mpx) | USB camera BigCatch EM-310C (3.2Mpx) | appropriate video processor and DVI2USB converter | none 4 |

| Image transfer | optical; C-mount endoscope coupler (f=25mm) | optical; C-mount endoscope coupler (f=25mm) | optical; C-mount endoscope coupler (f=25mm) | optical; C-mount endoscope coupler (f=25mm) | four wire | four wire |

| Housing | medical | medical | medical | medical | metal cylinder 5 | none / lacquer |

| Illumination | standard | standard | standard | standard | experimental 6 | none 4 |

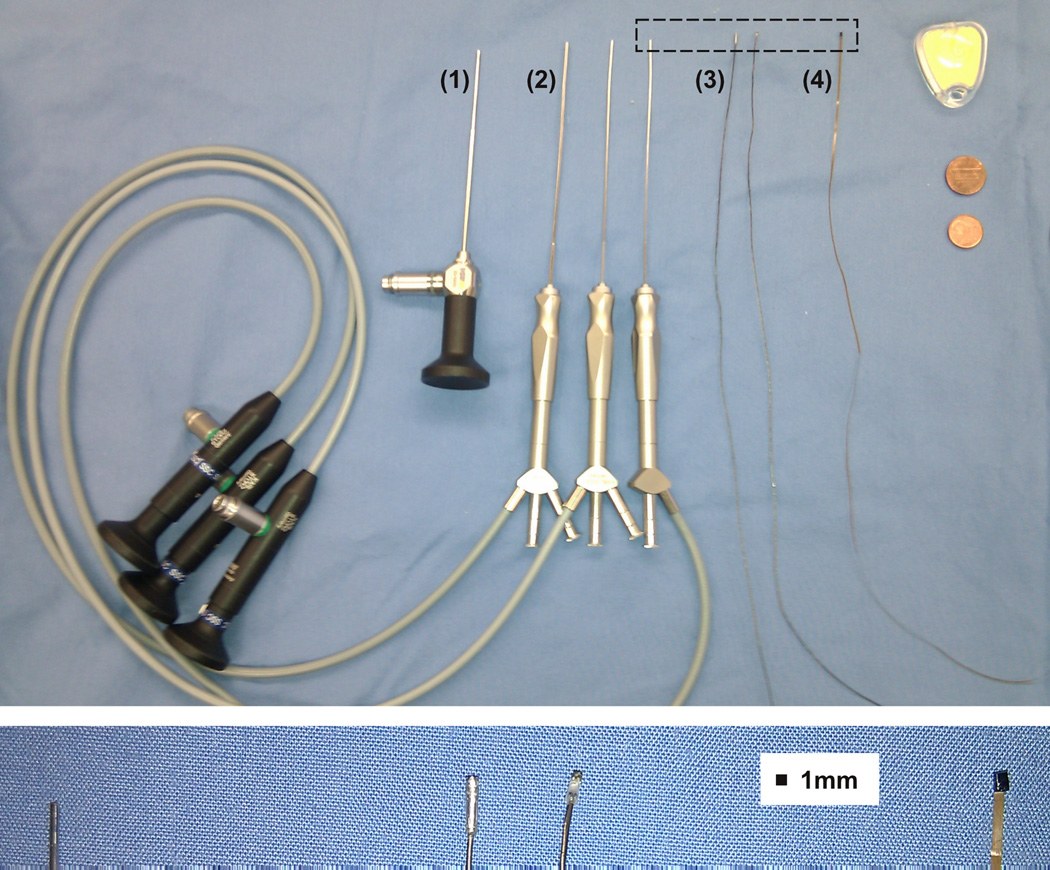

Two different models of small chip cameras were used: Image quality was tested with a camera from Medigus (Omer, Israel, model IntroSpicio™ 120) and spatial limitations were tested with both camera models (Medigus and a camera dummy from AWAIBA, Madeira, Portugal, model NanEye). Illumination was performed with a Karl Storz xenon light source (Tuttlingen, Germany, model 20133020) and a standard light cord for the the Hopkins rod (Gyrus ACMI, Southborough, MA, model explorent 23–5200) and the fiberscopes (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany, models sialendoscope 11581 A, 11582 A and 11583 A). The illumination for the chip-on-tip endoscope was experimental as, at present, there is no integrated lighting mechanism. For this we disassembled a fiber optic light guide (TRI-TRONICS®, Tampa, FL, model F-A-36T) and put several of the single fibers around or near the housing of the distal chip. Figure 1 illustrates the different endoscopes we used for this study.

Figure 1.

Endoscope comparison. Upper panel from left to right: (1) rigid endoscope with 1.7mm diameter at the tip, (2) three fiberscopes (sialendoscopes) with different diameters (1.6mm, 1.1mm, 0.9mm), (3) camera (Medigus, model IntroSpicio™ 120) for chip-on-tip endoscope with (1.2mm diameter × 5mm length) and without housing (diameter 1mm), (4) camera for chip-on-tip endoscope (AWAIBA, model NanEye, mechanical dummy, cuboid shape: 1mm × 1mm × 1.5mm), objects for comparison: insertion phantom from Cochlear Inc., United States penny and Euro 1 cent coin. Lower image: magnification of upper image dashed rectangle: 0.9mm sialendoscope and chip-on-tip cameras.

RESULTS

Part I

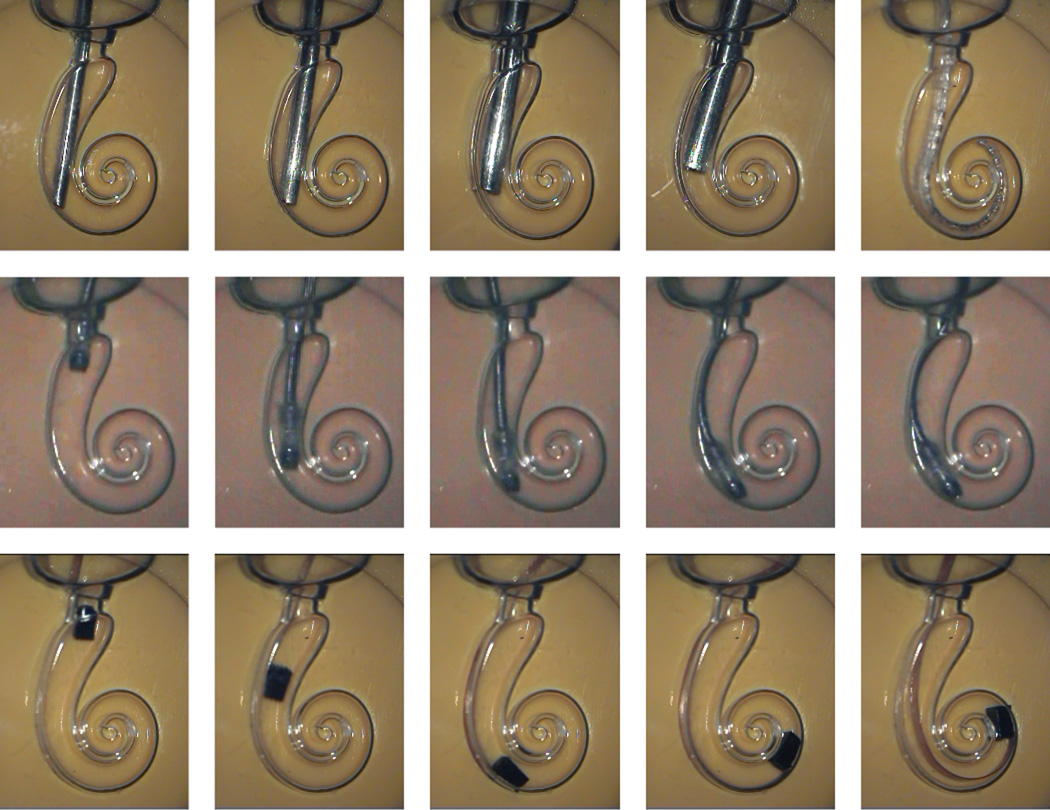

The insertion of the different endoscopes into the ST phantom is shown in Figure 2. Because of the curvilinear shape of the cochlea, both rigid and semi-flexible endoscopes could not follow the first turn (1st row, Figure 2). For comparison, a cochlear implant (CI) which easily navigates multiple turns is included in the last column of the first row of Figure 2 (Nucleus 24 Contour Advance Practice Electrode, Cochlear, Sydney, Australia). Sialendoscopes with 0.9mm and 1.1mm diameter (columns 1 and 2) could be easily inserted. However, the largest sialendoscope (diameter = 1.6mm, column 3) and rigid endoscope (diameter = 1.7mm, column 4) could only be partially inserted with maximal effort.

Figure 2.

Spatial analysis concerning depth and flexibility of the different endoscopes used during insertion into a scala tympani phantom from Cochlear Ltd. 1st row: sialendoscopes (column 1–3), rigid endoscope (column 4), practice electrode (column 5); 2nd row: camera chip from Medigus; 3rd row: camera chip from AWAIBA.

The 2nd and 3rd rows of Figure 2 show the two chip-on-tip endoscopes. The Medigus camera (center row) was used without its housing to allow more flexibility. Even with this modification, while the camera was small enough to navigate the basal turn, the wires emanating from the camera chip and the silicone coating prevented transmission around the basal turn. In the last row the camera chip from AWAIBA achieved a depth of 270°.

Part II

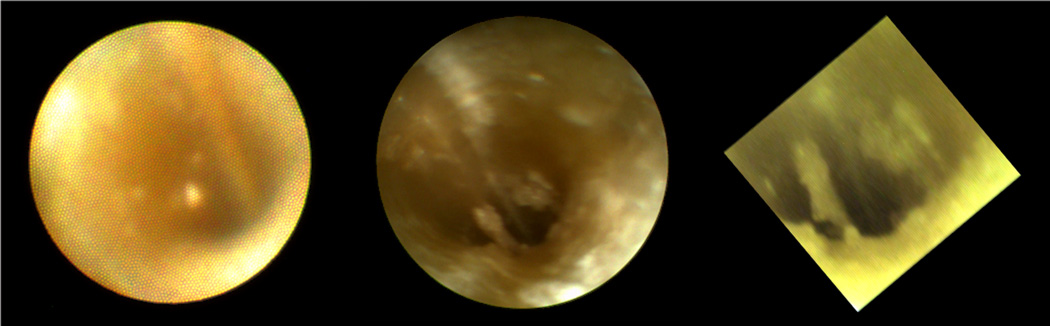

After testing the feasibility of inserting small camera (chip-on-tip endoscopes) into the ST phantom, a comparison of the image quality inside a human ST was performed. Figure 3 shows images with a sialendoscope (left), a rigid endoscope (center) and a chip-on-tip endoscope (right). The sialendoscope has approx. 6,000 fibers which are visible as the pixilation in the image. This severely limits resolution showing only rough visualization and orientation. With both the rigid endoscope and chip-on-tip endoscope, anatomical identification is achievable.

Figure 3.

Image comparison for the first temporal bone (sialendoscope, rigid endoscope; chip on tip endoscope). View in this left cochlea in from scala tympani towards the basal turn.

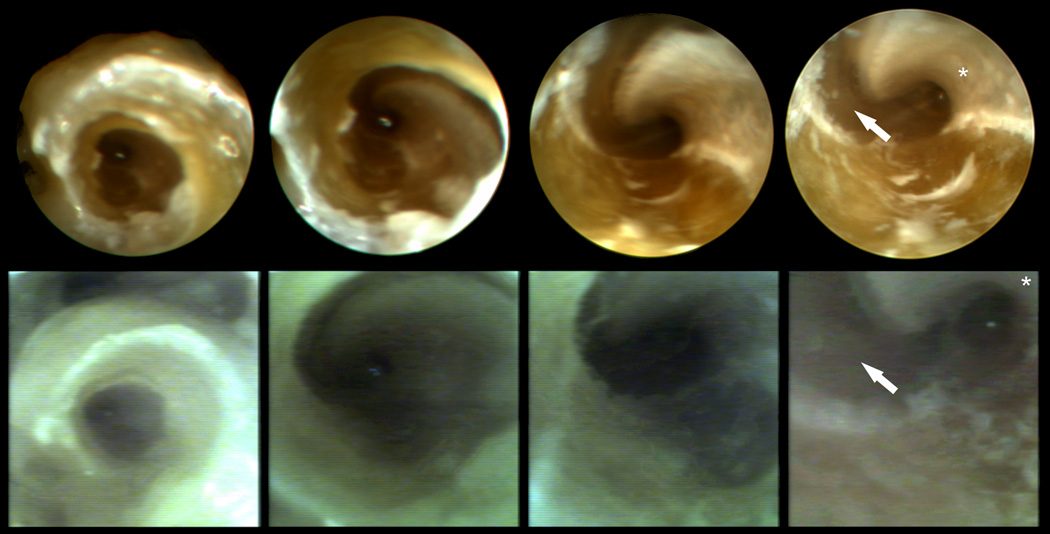

Further comparison was then made between the scopes with the better image quality – the rigid endoscope and the chip-on-tip endoscope – as shown in Figure 4. Both technologies allow visualization deep into the basal turn allowing excellent recognition of anatomy. It was possible to insert the chip on tip endoscope deeper than the rigid endoscope; however, the benefit of this was not clear as it could not pass the first turn (Figure 4, last column). Also evident is the distortion of color due, at least in part, to difficulties with illumination which were delivered via fiber optics. Nonetheless, the chip-on-tip endoscope clearly allows recognition of intracochlear anatomy.

Figure 4.

Image comparison for the second temporal bone (upper images rigid endoscope; lower images chip on tip endoscope). View in this left cochlea is from scala tympani towards the basal turn. The osseous spiral lamina is labeled with an asterisk and the basilar membrane with an arrow.

DISCUSSION

Researchers in the last decades have shown different aspects of intracochlear visualization, e.g. locating normal and abnormal structures [4,5], supporting laser ablation [6], determining blood flow [2] and correlating structures with the position of CI electrode arrays [8]. In this study we demonstrated the concept of using chip-on-tip endoscopes for intracochlear visualization of cadaveric ST. The chip-on-tip endoscopy images show most of the features and details which are visible with Hopkins rods despite pixel quantity that is at least 10-times less and an experimental illumination system.

Concerning overall chip-on-tip device size, individual imaging elements (corresponding to single pixels in the image) within the photodetecting sensor are now available at edge lengths of 1.43 µm—significantly smaller than the 2.2 and 3 µm imaging elements used in the Medigus and AWAIBA scopes, respectively. Thus, with today’s technology, the same quantity of pixels could be achieved with a device half as small as either chip-on-tip scope tested. This would allow room for illumination such as that provided by optical fibers or a light emitting diode.

Regarding optical resolution, while chip-on-tip cameras can output pixels in direct proportion to the quantity of imaging sensor elements, mounted lenses and illumination limit overall resolution. The needed contrast to determine a difference between two features is dependent upon reflection from illumination and refraction limits. The choice of lens systems has influence on the refraction limit as well as further parameters including field of view (FOV) and object distance. These optical parameters are dependent upon refractive index of the lens material as well as surrounding media (i.e. perilymphatic fluid) and the radii of the lens face. With sufficient illumination, the Medigus camera system has a minimum resolution of 8.8 line pairs per millimeter [personal communication]. This resolution corresponds to a projected pixel size of ≤ 60 µm at an object distance of 5 mm. The resolution value is strongly dependent on the above mentioned parameters.

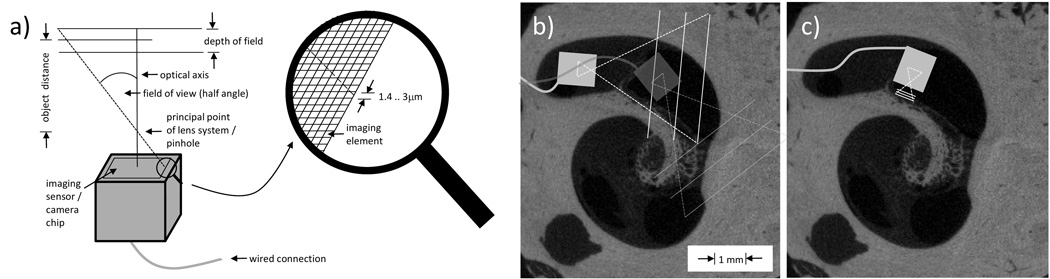

Ideally, an intracochlear chip-on-tip camera system would employ an adjustable lens system, e.g. tunable liquid lenses, which would allow alternating between wide angle view to orient and near angle view for maximal magnification. Figure 5a illustrates the terms of geometrical optics connected to chip-on-tip cameras for intracochlear visualization. The wide angle would be useful in determining which scala the camera is in, visualization of blockage of the scala (e.g. ossification), damage to the basilar membrane and/or osseous spiral lamina, and determination of optimal insertion direction for cochlear implants (Fig. 5b). By changing the lens properties to accommodate different surveillance areas sizes (Fig. 5c), resolution of 10 µm could allow identification of individual cells which have dimensions on this order of magnitude. Ongoing research on liquid microlenses, superlenses (negative refractive index lenses), and chip-microscopes will bring such exciting opportunities to fruition in the not-too-distant future (e.g. 5–10 years).

Figure 5.

(a) Illustration of geometrical optics for intracochlear chip-on-tip endoscopy. (b,c) The camera head (with wired connection) is shown relative to µCT images of the cochlea. (b) Currently available chip-on-tip cameras can navigate inside ST with a FOV of 60°. (c) With modifications to the lens (not currently available), magnified views of the osseous spiral lamina or other anatomy of interest would be possible.

A clear application of this technology would be to locate a chip-on-tip camera on the tip of a CI electrode which may enhance atraumatic and/or deeper insertion. As the cost of these electronic components drops to a predicted floor of several dollars per chip, they could be permanently embedded into the tip of the implant. Damage of the basilar membrane, wrong curling behavior, and shallow insertion could be avoided by such visualization. Additionally, data could be collected to investigate potential dependencies of certain anatomy and pathology in respect to the result of hearing restoration. The advantages and disadvantages concerning different endoscope types for visual controlled electrode insertion are listed in Table 2. We hypothesize that chip-on-tip endoscopy would be ideally suited for such once illumination issues are solved. Once visualization is possible, new challenges regarding tool design for intracochlear manipulation will emerge.

Table 2.

Overview of the different endoscope types and their characteristics concerning later integration of visual sensory into an electrode array.

| Endoscope type | Image quality | Illumination | Flexibility | Diameter | Volume | CI Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid | Best | Solved | None | Big | Big | Not possible |

| Optical fiber | Poor | Solved | Best | Small | Big | Difficult |

| Chip-on-tip | Good | Unresolved | Good | Middle | Small | Best |

squarish footprint: 1mm × 1mm

housing size; embedded camera chip is shorter

approx. 500,000 pixel during this study; in principle higher resolution possible, but limited by refraction, aperture and pixel density of the used camera

only mechanical dummies used

additional catheter material Ocrilon polyurethane16G, diameter 1.8mm, tip 1.7mm (study part II)

several light fibers (diameter 50µm) were included into the catheter (cp. 5)

Conclusion

We have shown the state of the art of endoscopic exploration of the human cochlea with established endoscopes and small cameras (chip-on-tip endoscopes). Additionally, feasibility is proven that the actual smallest available cameras fit inside ST to at least 270° and the quality of the images is between those of fiberscopes and rigid endoscopes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Award Number R01DC008408 and R01DC010184 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. LAK gratefully acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation within the project KA 2975/2-1. The authors thank the companies AWAIBA for the mechanical dummies of the NanEye camera and Karl Storz for loan of the sialendoscopes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr.-Ing. Lueder A. Kahrs, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, l.a.kahrs@vanderbilt.edu, Phone: (615) 936-2493, Fax: (615) 936-5515.

Theodore R. McRackan, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, theodore.r.mcrackan@vanderbilt.edu.

Robert F. Labadie, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, robert.labadie@vanderbilt.edu, Phone: (615) 936-2493, Fax: (615) 936-5515.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rose CJ, Ogden MA, Chole RA. Innovate Otolaryngology Edition. Vol. 2. Washington University St. Louis, Fall; 2010. [Accessed June 20]. p. 1. Available at: http://oto.wustl.edu/oto/otoweb.nsf/208a72445c0bb4e186256cde00604463/e3b768393bf8458f862571610073b8b8/$FILE/InnovateFall.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monfared A, Blevins NH, Cheung EL, Jung JC, Popelka G, Schnitzer MJ. In vivo imaging of mammalian cochlear blood flow using fluorescence microendoscopy. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:144–152. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000190708.44067.b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozluoglu LN, Akbasak A. Video endoscopy-assisted vestibular neurectomy: a new approach to the eighth cranial nerve. Skull Base Surg. 1996;6(4):215–219. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balkany T, Fradis M. Flexible fiberoptic endoscopy of the cochlea: human temporal bone studies. Am J Otol. 1991;12(1):46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkany T. Endoscopy of the cochlea during cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99(11):919–922. doi: 10.1177/000348949009901112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kautzky M, Susani M, Franz P, Zrunek M. Flexible fiberoptic endoscopy and laser surgery in obliterated cochleas: human temporal bone studies. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;18(3):271–277. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)18:3<271::AID-LSM9>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfister M, Maier H, Gummer AW, Preyer S. In vivo cochleoscopy through the round window Article in German. HNO. 1997;45(4):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s001060050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell AP, Suberman TA, Buchman CA, Fitzpatrick DC, Adunka OF. Flexible cochlear microendoscopy in the gerbil. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1619–1624. doi: 10.1002/lary.20979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritsch MH. Endoscopy of the inner ear. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42(6):1209–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivak MV, Jr, Fleischer DE. Colonoscopy with a VideoEndoscope: preliminary experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(84)72282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405(6785):417. doi: 10.1038/35013140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piepho T, Werner C, Noppens RR. Evaluation of the novel, single-use, flexible aScope for tracheal intubation in the simulated difficult airway and first clinical experiences. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(8):820–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waye JD, Heigh RI, Fleischer DE, et al. A retrograde-viewing device improves detection of adenomas in the colon: a prospective efficacy evaluation (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(3):551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaida M, Fukuda H, Kohno N. Clinical Experience with a New Type of Rhino-Larynx Electronic Endoscope PENTAX VNL-1530. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1994;1(1):57–62. doi: 10.1155/DTE.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schröck A, Stuhrmann N, Schade G. Flexible 'chip-on-the-tip' endoscopy for larynx diagnostics Article in German. HNO. 2008;56(12):1239–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00106-008-1783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eller R, Ginsburg M, Lurie D, Heman-Ackah Y, Lyons K, Sataloff R. Flexible laryngoscopy: a comparison of fiber optic and distal chip technologies-part 2: laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Voice. 2009;23(3):389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan H. For medical instruments, going small pays off big. BioPhotonics. 2010;17(9):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wäny M, Voltz S, Gaspar F, Chen L. Ultrasmall digital image sensor for endoscopic applications; Presented at the International Image Sensor Workshop; Jun 25–28, 2009; Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]