Abstract

Objective

To report the clinical presentation and oncologic outcomes of a series of patients who presented with an abdominal or pelvic mass and were diagnosed with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Methods

Data were obtained on all patients who presented with an abdominal or pelvic mass between September 2007 and June 2010 and who were ultimately diagnosed with a GIST. The patients' medical records were reviewed. A literature review was also conducted.

Results

Six patients were identified who met the inclusion criteria. All six patients had a tumor in the intestinal tract arising from the small bowel. The mean tumor size was 12 cm (range, 6 to 22 cm). A complete resection was achieved in five of the six patients. There were no intraoperative complications; one patient had a postoperative complication. Two patients were treated with imatinib after surgery. The mean follow-up time was 32 months (range, 0.3 to 40 months). At the last follow-up, five of the six patients were without any evidence of disease. One patient died of an unrelated hepatic encephalopathy. The incidence in our institution is 3%.

Conclusion

GISTs are uncommon; however, they should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with an abdominal or pelvic mass.

Keywords: Adnexal mass, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Incidental finding

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) represent 1% of all gastrointestinal tract neoplasms and have an approximate incidence of 10 to 20 cases per million individuals per year [1]. In the United States, approximately 4,500 new cases of GIST are diagnosed each year [1]. The average age of patients at presentation is 60 years, and there is no gender predilection [1-3]. GISTs may arise from the stomach (50-60% of GISTs), small bowel (20-30%), large bowel (10%), and esophagus (5%), or elsewhere in the abdominal cavity (e.g., omentum, mesentery) (5%) [4].

GISTs were initially described in the 1940s by Stout, who suggested that these tumors arose from the smooth muscle and therefore referred to them as leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas [5]. The concept that these tumors arise from the smooth muscle lasted until the advent of electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry. In 1983, Mazur and Clark [6] coined the term "GIST" to describe stromal tumors that had no differentiation into smooth muscle or into Schwann cells. In the late1990s, several groups noted a similarity between the neoplastic cells of GISTs and the interstitial cells of Cajal [7-9]. GISTs typically express the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit, also known as CD117 [4]. The prognosis of patients with a GIST is based on tumor size, mitotic rate, and organ of origin.

The published literature on GISTs in patients who present with an abdominal or pelvic mass is limited to isolated case reports and small case series [7-14]. The goal of this study was to report on a series of patients who presented with a presumptive diagnosis of ovarian cancer and who were ultimately found to have a GIST. We describe the clinical presentation, surgical management, adjuvant treatment, and overall outcome in these patients. In this report, we also summarize the published literature on GISTs presenting as ovarian cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was received from Instituto de Cancerologia, Clinica las Americas, Medellin, Colombia, data were collected on patients who presented to Instituto de Cancerologia with an abdominal or pelvic mass between September 2007 and June 2010. Data were abstracted from the patients' existing medical records on age, presenting symptoms, tumor size on physical examination, findings on imaging studies, serum CA-125 levels, intraoperative findings, primary site of disease, pathologic diagnosis, mitotic rate, adjuvant therapy, and disease status at last follow-up.

Patients were included in this study if they met the following criteria: complete medical records, radiologic imaging showing a pelvic or abdominopelvic mass, CA-125 levels recorded, and a final pathology diagnosis of a GIST. CA-125 levels were measured by microparticle enzymatic immunoassay, and normal values were defined as <35 U/mL. Pathologic diagnosis was confirmed by conventional methods and through immunohistochemistry using the following markers: c-Kit (CD117), desmin, smooth muscle actin, CD34, and S-100 protein.

We also performed a literature review on PubMed database, limited to the English language, using the following terms: "gastrointestinal stromal tumor," "adnexal mass," and "incidental finding."

RESULTS

Six patients met the inclusion criteria and are the subject of this report. The mean age was 59 years (range, 42 to 86 years). All patients were referred to the Instituto de Cancerologia with a presumptive diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The presentations of these patients were as follows: lower abdominal pain with duration ranging from 2 weeks to 3 months prior to consultation (4 patients), abnormal uterine bleeding with duration of 2 weeks (1 patient), and incidental finding of an adnexal mass on screening examination (1 patient).

On physical examination, all six patients had a palpable firm abdominal mass. On pelvic examination, four patients had a painful palpable mass and one patient had no abnormal findings; one patient did not allow pelvic examination. The mean size of the masses was 12 cm (range, 6 to 22 cm). On imaging studies, four patients had an ovarian mass visualized on both computed tomography and ultrasonography. The other two patients had a mass documented on computed tomography only (one patient) or ultrasonography only (one patient). The mean serum CA-125 level for all patients was 41.2 U/mL (range, 1.6 to 156 U/mL) and the mean level was 20.05. Only one patient presented with a CA-125 level greater than 35 U/mL (156 U/mL).

All patients underwent an exploratory laparotomy and had a preoperative diagnosis of ovarian malignancy. At the time of surgery, three patients were found to have a mass arising from the jejunum, and the other three patients were found to have a mass arising from the ileum. Two patients had incidental findings not described on the preoperative computed tomography or ultrasonography: hepatic metastatic nodules in one patient and a cirrhotic liver and ascites in the other patient. All patients underwent intestinal resection with end-to-end anastomosis. Only one patient had residual disease. This was the patient who was found to have hepatic metastatic nodules during the intraoperative assessment. There were no intraoperative complications. The postoperative course was complicated in one patient, who developed a postoperative ileus that resolved after 6 days of conservative management. The mean hospital stay for all patients was 6 days (range, 5 to 8 days).

On final pathology review, all patients had immunohistochemical analysis and all stained positive for CD117, two patients had disease considered to be intermediate risk for recurrence and four had disease considered as high risk. The clinical oncologist reviewed all cases. The patients with intermediate-risk disease did not receive adjuvant therapy due their low mitosis rate. Two of the patients with high-risk disease were treated with imatinib (400 mg daily) after surgery. One of these two patients had a high rate of mitosis (28 per 50 high-power fields [HPF]) and underwent therapy with imatinib for a year; the other patient had evidence of residual disease in the liver and is still on imatinib treatment to date. One of the patients with high-risk disease did not receive adjuvant therapy because of the low mitotic rate of the tumor. The other patient with high-risk disease died soon after surgery from encephalopathy associated with cirrhosis. At a mean follow-up time of 32 months (range, 0.3 to 40 months), all five patients who were still alive were without any evidence of disease. As there were only 6 patients, this would not allow for appropriate statistical analysis. A total of approximately 200 patients with ovarian cancer were operated at Instituto de Cancerologia Las Americas during the time span of the study. Based on this information the incidence is approximately 3%.

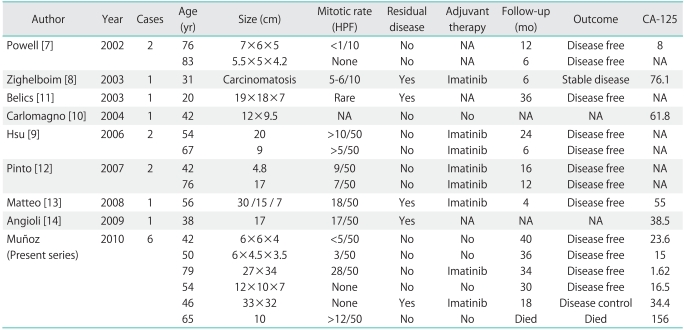

As a result of our literature review, we found eight reports including 11 patients who presented with an abdominal or pelvic mass and were ultimately diagnosed with a GIST. The details on these patients as well as the six patients in the current series are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the 11 previously reported patients was 53 years (range, 20 to 83 years). Most patients presented complaining of an abdominal mass. The diagnostic images usually showed irregular lesions with areas of necrosis of heterogeneous content ranging in size from 5 cm to giant or even carcinomatosis. All 11 patients underwent surgical resection, and six (54%) of them were treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib. The mean reported follow-up time was 12.2 months (range, 4 to 36 months). No patients were reported to have relapsed during follow-up; one patient had carcinomatosis at the time of surgery, progression before starting imatinib, but stable lesions at 6 months [8].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

HPF, high-power fields; NA, not available.

DISCUSSION

GISTs are rare tumors and may present a diagnostic dilemma. Complete surgical resection is considered the standard treatment for localized tumors. Segmental intestinal resection is often necessary as these tumors present with an exophytic (bulky growth) rather than infiltrative pattern. When segmental resection is not possible, a wide, en bloc resection should be performed [10,15]. For metastatic and recurrent disease, surgery remains the first choice of therapy [1,15].

Approximately 95% of GISTs express the marker c-kit (CD117) [16]. Detection of receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit status is critical in the management of GISTs since tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib (Gleevec), sunitinib (Sutent), sorafenib (Nexavar), dasatinib, IPI504, oblimersen (Genasense), and perifosine have been shown to be effective treatments [4,17]. The use of such tyrosine kinase inhibitors is considered the standard therapy in patients with metastatic or unresectable disease [15,17].

The preferred imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with a suspected GIST is enhanced computed tomography. The predominant pattern is a heterogeneously enhancing exophytic mass. Gastric lesions are characterized by a homogeneous enhancement, while small bowel lesions are more heterogeneous. Since most GISTs grow exophytically and do not compromise the bowel concentrically, findings consistent with intestinal obstruction are not very common even with very large masses. Mesenteric extension may occur with encasement of adjacent organs [18-21]. Distal small bowel tumors and those arising from the sigmoid colon and rectum may be erroneously identified as gynecologic cancers [22].

Gross histopathologic findings typically include a fish-flesh appearance of soft consistency. Tumors can be necrotic or present with cystic degeneration. Approximately 70% are composed of spindle cells, 20% of epithelioid cells, and 10% have a mixed phenotypic appearance [22-24]. Other markers expressed by these tumors are CD34 (70% of tumors), smooth muscle actin (30%), h-caldesmon (60%), and S-100 (5%) [24,25]. The DOG1 (discovered on GIST) marker is a fragment of cDNA encoding a protein whose function is unknown. This marker may be helpful when a GIST is negative for c-kit; DOG1 has high sensitivity (94.4%) in the diagnosis of GISTs and is positive in 30% of those that are negative for c-kit [26,27].

The prognosis of patients with a GIST is based on tumor size and number of mitoses. Tumors smaller than 2 cm with fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPF are considered very low risk for recurrence. Tumors measuring 2 to 5 cm with fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPF are considered low risk. Tumors smaller than 5 cm with 6 to 10 mitoses per 50 HPF and tumors measuring 5 to 10 cm with fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPF are considered intermediate risk. High-risk tumors are those measuring 5 to 10 cm with 6 to 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, any tumor larger than 10 cm, and any tumor with more than 10 mitoses per 50 HPF [2,12,28].

All patients diagnosed with a GIST that is considered intermediate risk or high risk should be treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor-either imatinib 400 mg per day (first choice) or sunitinib 50 mg per day for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off (second choice) either of them for at least 1 year. These regimens have been shown to improve disease-free survival and overall survival [1,16,17,26,27,29]. In patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, studies have documented a relapse-free survival rate of 97% at 1 year, a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 65%, and a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 68% [4,29].

Unlike tyrosine kinase inhibitors, systemic chemotherapy has minimal effect on GISTs and thereby is not recommended for either neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy [1]. Complete resection is curative in patients with low-risk tumors, even without lymph node resection; lymphadenectomy does not improve survival since lymph node metastases are rare [1,16], and there is no need for adjuvant therapy in both very low risk and low risk patients. In patients with unresectable GISTs, neoadjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors can lead to a less extensive surgical procedure and decrease the risk of tumor rupture and bleeding during resection [1,17,18,29]. As cited by several authors, tumors arising in the small intestine have been shown to be more aggressive and are associated with a poorer prognosis and higher rate of progressive disease than those arising from the stomach [16,30,31].

In summary, the diagnosis of a GIST should be entertained in all patients diagnosed with an abdominal or pelvic mass. All patients with intermediate and high-risk GISTs should be treated postoperatively with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Schnadig ID, Blanke CD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: imatinib and beyond. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;7:427–437. doi: 10.1007/s11864-006-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joensuu H. Current perspectives on the epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2006;4:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schubert ML, Moghimi R. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s11938-006-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quek R, George S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a clinical overview. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stout AP. Bizarre smooth muscle tumors of the stomach. Cancer. 1962;15:400–409. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196203/04)15:2<400::aid-cncr2820150224>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastric stromal tumors: reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:507–519. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell JL, Kotwall CA, Wright BD, Temple RH, Jr, Ross SC, White WC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor mimicking ovarian neoplasia. J Pelvic Surg. 2002;8:117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zighelboim I, Henao G, Kunda A, Gutierrez C, Edwards C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu S, Chen SS, Chen YZ. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors presenting as gynecological tumors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;125:139–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlomagno G, Beneduce P. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) masquerading as an ovarian mass. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belics Z, Csapo Z, Szabo I, Papay J, Szabo J, Papp Z. Large gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as an ovarian tumor: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:655–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto V, Ingravallo G, Cicinelli E, Pintucci A, Sambati GS, Marinaccio M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors mimicking gynecological masses on ultrasound: a report of two cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:359–361. doi: 10.1002/uog.4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matteo D, Dandolu V, Lembert L, Thomas RM, Chatwani AJ. Unusually large extraintestinal GIST presenting as an abdomino-pelvic tumor. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angioli R, Battista C, Muzii L, Terracina GM, Cafa EV, Sereni MI, et al. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a pelvic mass: a case report. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:899–902. doi: 10.3892/or_00000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Choi H, Debiec-Richter M, Dei Tos AP, et al. Consensus meeting for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: report of the GIST Consensus Conference of 20-21 March 2004, under the auspices of ESMO. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:566–578. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Barusevicius A, Miettinen M. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota T. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and imatinib. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:184–189. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:283–304. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandrasegaran K, Rajesh A, Rydberg J, Rushing DA, Akisik FM, Henley JD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:803–811. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong JS, Zuo M, Yang P, Zang D, Zhang Y, Xia L, et al. Value of CT in the diagnosis and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: CT and MR imaging features with clinical and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1607–1612. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Carr NJ, Emory TS, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Hirohashi S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: consistent CD117 immunostaining for diagnosis, and prognostic classification based on tumor size and MIB-1 grade. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:669–676. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liegl B, Hornick JL, Corless CL, Fletcher CD. Monoclonal antibody DOG1.1 shows higher sensitivity than KIT in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, including unusual subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:437–446. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318186b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demetri GD, Benjamin RS, Blanke CD, Blay JY, Casali P, Choi H, et al. NCCN Task Force report: management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)--update of the NCCN clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5(Suppl 2):S1–S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raut CP, DeMatteo RP. Prognostic factors for primary GIST: prime time for personalized therapy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:4–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9634-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassan I, You YN, Shyyan R, Dozois EJ, Smyrk TC, Okuno SH, et al. Surgically managed gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comparative and prognostic analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:52–59. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9633-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trent JC, Benjamin RS. New developments in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18:386–395. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000228747.02660.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silberhumer GR, Hufschmid M, Wrba F, Gyoeri G, Schoppmann S, Tribl B, et al. Surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1213–1219. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das A, Wilson R, Biankin AV, Merrett ND. Surgical therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1220–1225. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0885-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]