Abstract

Objective

A strong relation between negative affect and craving has been demonstrated in laboratory and clinical studies, with depressive symptomatology showing particularly strong links to craving and substance abuse relapse. Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP), shown to be efficacious for reduction of substance use, uses mindfulness-based practices to teach alternative responses to emotional discomfort and lessen the conditioned response of craving in the presence of depressive symptoms. The goal of the current study was to examine the relation between measures of depressive symptoms, craving, and substance use following MBRP.

Methods

Individuals with substance use disorders (N=168; age 40.45, (SD=10.28); 36.3% female; 46.4% nonwhite) were recruited after intensive stabilization, then randomly assigned to either eight weekly sessions of MBRP or a treatment-as-usual control group. Approximately 73% of the sample was retained at the final four-month follow-up assessment.

Results

Results confirmed a moderated-mediation effect, whereby craving mediated the relation between depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory) and substance use (Time Line Follow Back) among the treatment-as-usual group, but not among MBRP participants. Specifically, MBRP attenuated the relation between postintervention depressive symptoms and craving (Penn Alcohol Craving Scale) two months following the intervention (f2=.21). This moderation effect predicted substance use four-months following the intervention (f2=.18).

Conclusion

MBRP appears to influence cognitive and behavioral responses to depressive symptoms, partially explaining reductions in postintervention substance use among the MBRP group. Although preliminary, the current study provides evidence for the value of incorporating mindfulness practice into substance abuse treatment and identifies one potential mechanism of change following MBRP.

Keywords: Mindfulness based relapse prevention, substance use, craving, negative affect, depression

Addiction has generally been characterized as a chronic and relapsing condition (Connors, Maisto, & Zywiak, 1996; Leshner, 1999). Research on the relapse process has implicated numerous risk factors that appear to be the most robust and immediate predictors of posttreatment substance use, including negative affect, craving or urges, interpersonal stress, motivation, self-efficacy, and ineffective coping skills in high-risk situations (Connors et al.,1996; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). Targeting these risk factors during treatment, either pharmacologically (e.g., naltrexone to reduce alcohol craving; Richardson et al., 2008) or behaviorally (e.g., coping skills training; Monti et al., 2001), has become a priority for substance abuse researchers and clinicians.

Depression, Craving and Relapse

The significant roles of negative affective states and craving in the substance use relapse process have been described for over 30 years (e.g., Ludwig & Wikler, 1974; Solomon & Corbit, 1974). Craving, the subjective experience of an urge or desire to use substances (Kozlowski & Wilkinson, 1987), has been shown to strongly predict reinstatement of substance use for all major drugs of abuse (e.g., Hartz, Frederick-Osborne, & Galloway, 2001; Hopper et al. 2006; Shiffman et al., 2002). Negative affect has been shown to be a prominent cue for craving in both laboratory and clinical studies (e.g., Cooney, Litt, Morse, Bauer, & Gaupp, 1997; Perkins & Grobe, 1992; Shiffman & Waters, 2004; Sinha & O’Malley, 1999; Stewart, 2000; Wheeler et al., 2008), and both the experience of negative affective states and the desire to avoid these aversive states have been described as primary motives for substance use (e.g., Wikler, 1948). Specifically, depressive symptomatology has been linked to re-initiation of drug use following periods of abstinence (e.g., Curran, Booth, Kirchner & Deneke, 2007; Witkiewitz & Villarroel, 2009), and self-reported depression has been shown to predict substance use treatment outcomes (e.g., Hodgins, el Guebaly, & Armstrong, 1995; Cornelius et al., 2004; Greenfield et al., 1998).

The relation between depression and substance use is also evident in the disproportionately higher rates of substance use relapse in individuals with affective disorders (Conner, Sorensen, & Leonard, 2005; Hasin & Grant, 2002; Kodl, Fu, Willenbring, Gravely, Nelson, & Joseph, 2008). Individuals with depression show a particularly strong relation between depressive symptoms and both craving and relapse (Gordon, Sterling, Siatkowski, Raively, Weinstein & Hill 2006; Zilberman, Tavares, Hermano; Hodgins & el-Guebaly, 2007; Curran, Flynn, Kirchner, & Booth, 2000; Levy, 2008).

Mechanisms of the relation between depressive symptoms, craving and relapse may be explained by a negative-reinforcement withdrawal model (Wikler, 1948). Baker and colleagues (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004) proposed that attempts to avoid negative affect during withdrawal produce the primary motive for resumption of drug use, and evidence from recent clinical, laboratory and ecological momentary assessment studies support this model (e.g., Armeli, Feinn, Tennen, & Kranzler, 2006; Carter et al., 2008; Perkins, Ciccocioppo, Conklin, Milanak, Grottenthaler, & Sayette, 2008). Research on the roles of brain systems and neurotransmitters provide further support. Persistent substance use leads to disruptions in several neurotransmitter systems, including both dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens and increased corticotropin releasing factor in the central nucleus of the amygdala, which are central to affective changes and stress responses during withdrawal. These disruptions may increase vulnerability to relapse when experiencing craving (Koob, 1988; Weiss, Markou, Lorang, & Koob, 1992; see Weiss 2005 for a review). Therefore, longtime substance users may be particularly susceptible to increased depressive symptoms, heightening their motivation to seek relief through use of substances, and consequently increasing the intensity of their craving.

Teasdale and colleagues (Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 2000) proposed the use of mindfulness practices to address this potential link between negative mood states and further problematic cognitive patterns that may lead to relapse. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for depression (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), a relapse prevention program for individuals with past episodes of major depression, was designed to reduce the depressive thinking that can lead to full depressive relapse. The treatment focuses on recognizing depressive thoughts, sensations and feelings that can be risk factors for relapse to depression. Clients learn to accept these experiences as separate from themselves and as transient or subject to change, thereby interrupting the cognitive processes that may contribute to depressive relapse. Importantly, MBCT has been found to be most effective for those with three or more previous depressive episodes as compared to their treatment-as-usual counterparts (Teasdale et al., 2000; Ma & Teasdale, 2004). Segal, Teasdale and Williams (2004) hypothesized MBCT might be of greater help to those with a greater association of depressive thinking and severely depressed mood.

Similarly, individuals with substance abuse histories may habitually react to depressive thinking or mood states with relapse-related thoughts or cravings due to past associations of depressive states with craving and substance use relapse. Through increased awareness of these cognitive and emotional patterns, and through learned alternative responses, mindfulness-based techniques may attenuate the conditioned link between depressive symptoms, craving and relief-seeking through substance use.

Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention

A recently developed behavioral intervention, Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP; Bowen, Chawla & Marlatt, in press; Witkiewitz, Marlatt, & Walker, 2005) combines Marlatt’s cognitive behavioral relapse prevention program (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985) with mindfulness practice, using a similar structure to that of MBCT. MBRP was designed to directly target negative mood, craving, and their roles in the relapse process. MBRP was based largely upon the content of MBCT, offering skills in cognitive behavioral relapse prevention (e.g., identifying high-risk situations, coping skills training) and mindfulness meditation. Clients typically meditate for 30–45 minutes in session and are assigned approximately 45 minutes of daily meditation, using audio-recorded instructions. The mindfulness practices are intended to increase discriminative awareness and acceptance, with a specific focus on affective and physical discomfort, teaching clients to observe physical, cognitive, emotional, or craving states without “automatically” reacting. Through formal meditation practices, other mindfulness-based exercises, and discussion, clients practice a nonjudgmental approach to negative affective states, learning to “investigate” the emotional, physical and cognitive components of experience, rather than immediately attempting to escape them. It is hypothesized that clients’ mindful recognition of and attention to problematic cognitive and affective states provide a “pause,” interrupting the habitual reaction. Over time, repeated exposure to previously avoided experience (e.g., depressive states), in the absence of habitual responses (e.g., substance use), may weaken the response of craving in the presence of emotional discomfort.

Recently, Bowen and colleagues (Bowen, Chawla, Collins, et al., 2009) conducted a pilot efficacy trial of an aftercare program following an intensive stabilization period, consisting of either inpatient or intensive outpatient treatment. The study evaluated substance use outcomes up to four months following postintervention assessment among participants randomly assigned to either an eight-week closed-cohort MBRP course or their standard rolling admission treatment-as-usual aftercare (TAU), which consisted of agency-delivered services based on the 12-step model (Lile, 2003) and psychoeducational content. Results suggested those receiving intensive stabilization + MBRP, when compared to intensive stabilization + TAU, demonstrated significantly lower rates of substance use, greater decreases in craving, and greater increases in the “acting with awareness” subscale of the Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006) across the four-month follow-up period. Significantly greater decreases in craving were found in the MBRP group as compared to the TAU group, and these decreases significantly mediated the relation between intervention group and substance use outcomes. The study offered preliminary support for the efficacy of the integration of mindfulness and relapse prevention strategies in the prevention of substance abuse relapse. Further evaluation of the potential mediating processes involved, however, is needed.

Following up on the significant mediating effect of craving that was reported by Bowen and colleagues (2009), the current study was designed to further examine one hypothesized mechanism of change following MBRP. Based on previous research, described above, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms and craving would be positively correlated with one another, and both would be significantly related to postintervention substance use. We further hypothesized that participation in MBRP would attenuate the relation between depressive symptoms and craving, which would subsequently decrease substance use.

Specifically, we were interested in testing the hypotheses that 1) there is a strong, positive relation between postintervention depressive symptoms, craving two months following the intervention, and days of substance use following the intervention; 2) the relation between depression symptoms and substance use can be partially explained by individuals’ subjective reports of craving; 3) intervention assignment will attenuate relations between depressive symptoms and craving, and 4) there is an interaction between intervention assignment, depressive symptoms, and craving, in the prediction of substance use. Given the focus of MBRP on helping clients to experience discomfort with decreased reactivity, we hypothesized that individuals in MBRP would be less likely to report craving in response to higher depression scores, subsequently decreasing their substance use.

Methods

Sample

Participants in the original study (N=168; Bowen, Chawla, Collins et al., 2009) were recruited from a private, nonprofit public service agency which provided both inpatient and intensive outpatient care for alcohol and other drug use disorders. All participants were fluent in English, and had completed intensive outpatient or inpatient treatment within the previous two weeks. Excluded from the study were those with current psychosis, dementia, imminent suicide risk, significant risk for withdrawal, inability to attend treatment, or those needing more intensive treatment due to high risk of relapse or continued heavy use, as determined by agency staff.

The majority of participants were male (63.7%), ranged in age from 18 to 70 years old (M= 40.45, SD=10.28), and identified primarily as White (not Hispanic, 53.6%), African American (28.6%), Native American (7.7%), or Hispanic/Latino (6.0%). Approximately 41.3% reported being unemployed, 62.3% earned less than $4999 per year, and 71.6% had a high-school diploma. The primary drugs of abuse were alcohol (45.2%), cocaine/crack (36.2%), and methamphetamine (13.7%). Approximately 19% of the sample reported polydrug abuse.

Measures

All measures were self-report, and were administered via a web-based assessment program with staff available to assist participants in using the assessment interface. Research has found no significant differences between paper-and-pencil and web administration of commonly utilized measures (Miller, et al., 2002). Demographics were assessed at baseline only. All other measures were administered at baseline, postintervention (immediately following the 8-week course), and at two and four months following postintervention.

Substance Use

The Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was used to assess alcohol or other drug use. Participants reported the number of days on which they had used alcohol or used other drugs over the past 60 days using a calendar format. The current study used calendar data from the four-month assessment, representing the total days of use during the 60 days between the two-month and four-month assessments. The TLFB has demonstrated good reliability and validity, with no significant differences between online and in-person administration (Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

Alcohol and Drug Craving

The Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS; Flannery, Volpicelli & Pettinati, 1999), a five-item self-report measure, was adapted to include craving for both alcohol and other drugs. The PACS measures frequency, intensity, and duration of craving, as well as an overall rating of craving for the previous week. The PACS has shown excellent internal consistency and predictive validity for alcohol relapse. The internal consistency of the PACS in the current sample was 0.87.

Depression

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI; Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996), a measure consisting of 21 multiple-choice format items assessing specific symptoms of depression. The BDI has shown high reliability across diverse populations (e.g., Storch, Roberti & Roth, 2004; Steer, Cavalieri, Leonard & Beck, 1999). Internal consistency in the current sample was 0.92.

Intervention

MBRP was delivered by two therapists to groups of 6–10 participants. Closed cohorts met weekly for eight two-hour sessions. Sessions included guided meditations, experiential exercises, and discussion. Participants were assigned daily exercises to practice between sessions, and were given CDs for daily meditation practice. RP practices (based on the program by Daley & Marlatt, 2006) were integrated into the mindfulness-based skills. MBRP therapists held master’s degrees in psychology or social work, and all had a background in cognitive-behavioral interventions. All sessions were audio recorded, and treatment fidelity was assessed by a team of coders who were trained to identify key content- and style-related components of MBRP, using The Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention Adherence and Competence Scale, a measure of treatment integrity for MBRP (MBRP-AC; Chawla, Collins, Bowen, Hsu, Grow, Douglass, & Marlatt, in press). Ratings by independent raters, demonstrating high interrater reliability and adequate internal consistency, suggested that therapists were adherent to the treatment protocol, therapeutic style, and discussion of core concepts (Chawla et al., in press).

Participants in the TAU condition continued in their standard, rolling admission outpatient aftercare, which included work in the 12-step model, process-oriented groups, and psychoeducation. Relapse prevention skills, based upon Gorski’s (2007) disease model of alcohol and drug addiction, were included in some of the groups. Therapists facilitating the TAU groups were licensed Chemical Dependency Counselors, with diverse clinical training and experience.

Procedure

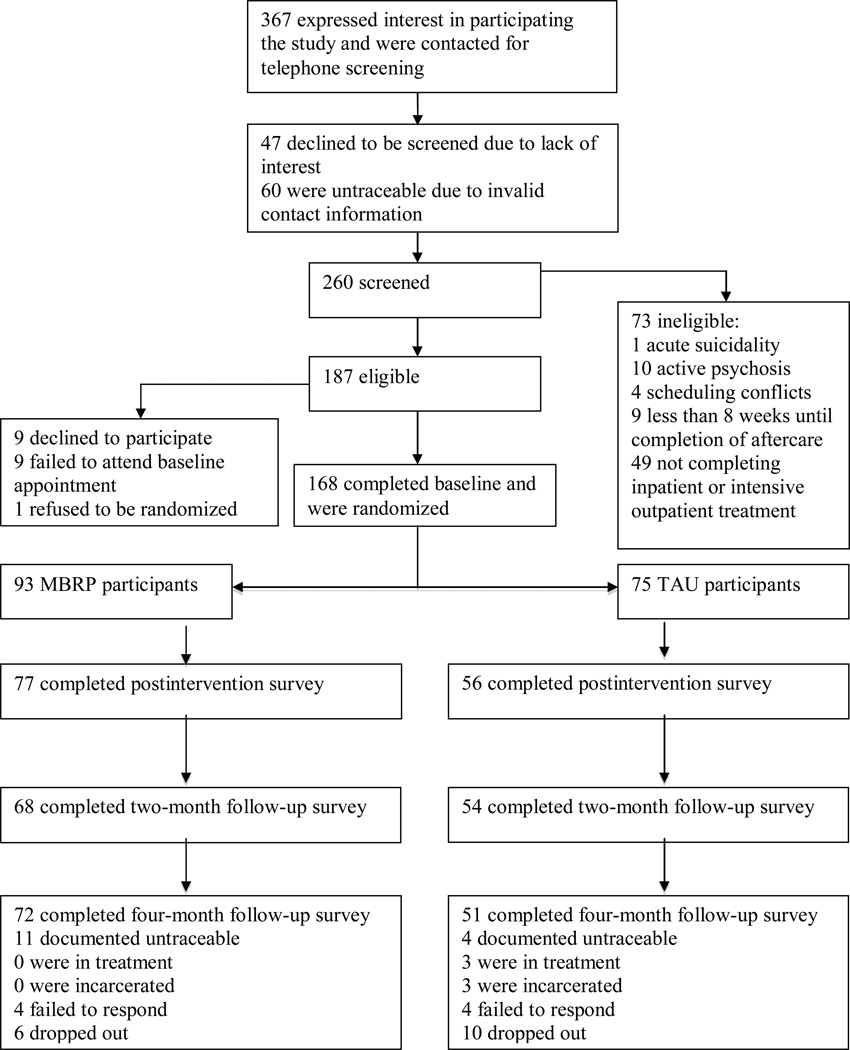

All study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Board. Participants were recruited close to completion of their inpatient or outpatient treatment. Recruitment started in April 2007 and ended in October 2007 and all follow-up assessments were completed by May 2008. As seen in Figure 1, 260 participants were screened for inclusion in the study and 187 met criteria for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion included acute suicidality (n = 1), active psychosis (n = 10), inability to participate due to scheduling conflicts (n = 4), having less than 8 weeks until completion of aftercare (n = 9), and not completing inpatient or intensive outpatient treatment (n = 49). Of those who met inclusion criteria, nine individuals declined participation, nine failed to complete the baseline assessment, and one refused randomization, reducing the overall sample to 168. This sample size was determined by the inpatient and intensive outpatient completion rates at the facility during the two-year study period and provided sufficient power to detect a medium effect of intervention on substance use outcomes. Interested and eligible individuals were randomly assigned via a web-based random number sequencer (http://www.randomizer.org) to MBRP (n = 93) or TAU (n = 75) following completion of a baseline assessment. Participants were randomly oversampled for the MBRP condition due to initial concerns about potentially higher rates of attrition in the MBRP group. The random number sequence described above was generated by graduate research assistants at the baseline assessment appointment. Graduate research assistants, participants, and those administering the interventions were aware of group assignment. All participants were compensated with gift cards upon completion of each assessment. No adverse events or side effects were reported by participants in either group.

Figure 1.

CONSORT participant flow diagram.

Statistical Analyses

To examine the hypotheses outlined above, a series of path models were estimated using Mplus version 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). In all path models, intervention assignment and depression scores at postintervention were entered as the independent variables, craving at the two-month follow-up was included as the mediator, and days of alcohol or other drug use at the four-month follow-up period was the dependent variable. Baseline craving and baseline depression scores, number of treatment hours received (including intervention hours and other treatment services received at the agency), baseline days of use, gender and race were included as covariates in all analyses. All models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) via the expectation maximization algorithm, which provides estimates of the variance-covariance matrix for all available data, including those individuals who have incomplete data on some measures. FIML is considered to be superior to other methods of handling missing data (e.g., listwise deletion), when data are missing at random (Schafer, 1997). Attrition analyses indicated that only postintervention depression was significantly related to completion status (t = 2.54, p = 0.01) and data were thus assumed to be missing at random with postintervention depression included in the model. Thus, our effective sample size for all models was 168. All analyses were intention-to-treat, thus the sample sizes per group were 93 and 75 for MBRP and TAU, respectively.

Preliminary data screening indicated that the distribution of the total days of use variable was highly skewed and kurtotic. Given that days of use are count data, a negative binomial distribution was first considered for all analyses. A comparison of the negative binomial models with models that assumed a normal distribution suggested that the results from the latter models were very robust to the violation of normality, and assuming a negative binomial distribution did not greatly alter the main coefficients of interest. Methods for testing moderated mediation using count outcomes and the negative binomial distribution have not been thoroughly examined. Thus, all analyses were conducted using the normal distribution. To reduce kurtosis, the days of use outcome variable was square root transformed, and after making the transformation multivariate normality was assessed for all variables to be included in the analysis using Mardia’s (1970) test of multivariate skewness and kurtosis. Mardia’s coefficient of skewness (M3 = 0.238, p = 0.07) and kurtosis (M4 = 5.219, p = 0.07) indicated the assumption of multivariate normality was not significantly violated.

To test the first hypothesis that there is a strong, positive relation between depressive symptoms, craving and substance use, we examined the associations between depression scores, craving scores and substance use outcomes for both intervention conditions using path analyses. The second hypothesis was to determine whether the relation between depressive symptoms and substance use could be explained by subjective reports of craving. To test this hypothesis we conducted analyses of simple mediation effects of craving in the relation between depression scores and substance use, using the product of coefficients method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). The product of coefficients method involves the multiplication of regression coefficients for the regression of the mediator on the independent variable (a-path) and for the regression of the outcome on the mediator (b-path) with the independent variable included in the model (c-path), and with a*b considered the mediated effect. An effect size, representing proportion of variance explained by the mediated effect, can be calculated by dividing the amount of variance in the outcome explained by the mediated effect by the total amount of variance in the outcome explained by both the mediator and the independent variable (MacKinnon, 2008). The simple mediation effects were estimated in Mplus using a maximum likelihood estimator and 1000 bootstrap draws to obtain confidence intervals for the indirect effect. The mediation models were evaluated using multiple indices of model fit: a nonsignificant chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI) values greater than 0.95, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values less than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). The commonly reported Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was not used because the RMSEA tends to over reject true models when the sample size is small (n ≤ 250; Hu & Bentler, 1998).

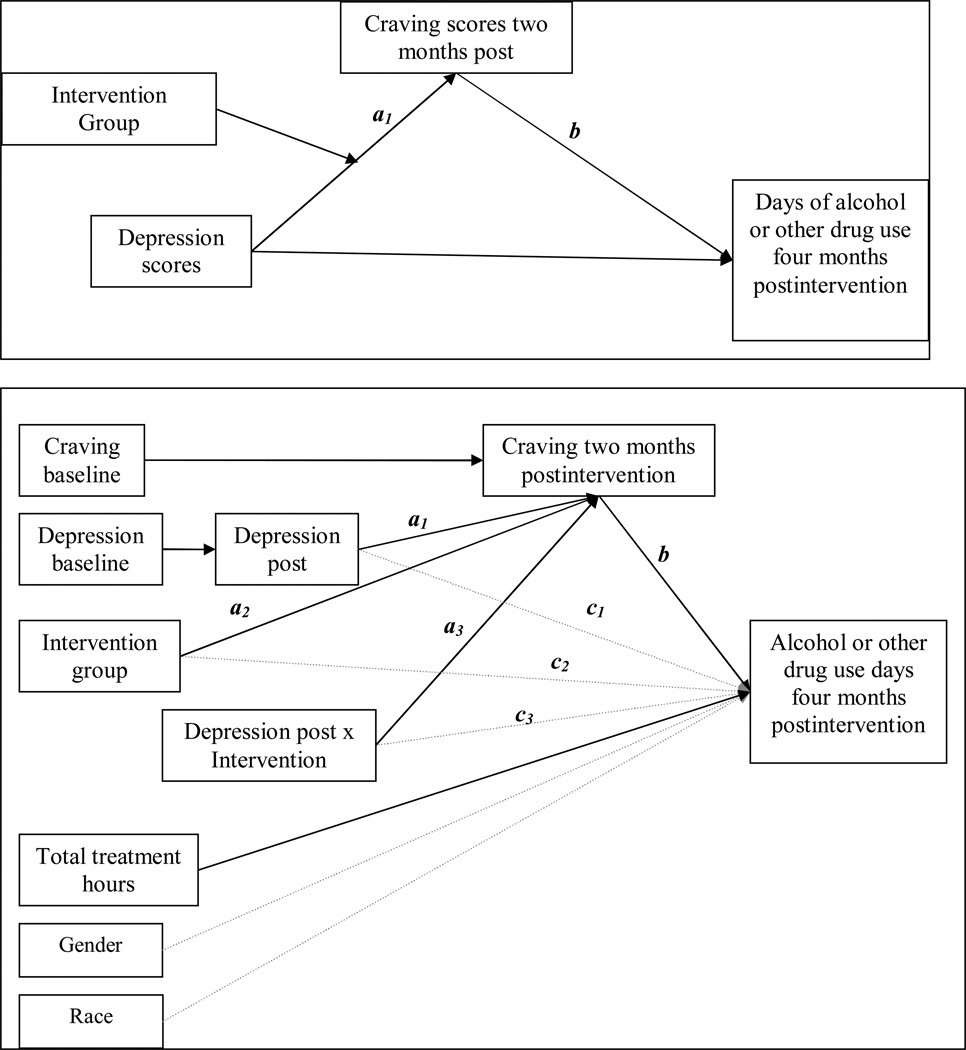

After testing the unconditional mediation effects, the final two hypotheses, moderation and moderated mediation, were examined (i.e., conditional indirect effect; Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007) by incorporating the mean-centered depression scores-by-intervention interaction into the model as independent variables using the methods described by Aiken & West (1991). First, the moderating hypothesis, that intervention assignment would attenuate the relation between depressive symptoms and craving, was tested by incorporating the depressive-symptoms-by-intervention interaction in the path model (shown in Figure 2a)1. Second, the moderated mediation hypothesis was examined by estimating the depressive-symptoms-by-intervention interaction predicting days of use via craving (indirect effect of a3*b). This model (shown in Figure 2b) provides a test of whether the attenuation of the relation between depressive symptoms and craving among MBRP participants predicted days of substance use postintervention. Although many variants of moderated-mediation or mediated-moderation can be tested we used the model identified as “Model B” by Preacher and colleagues (2007), in which the a-path of the indirect effect is moderated by some other variable. In this instance of moderated mediation, the relation between depressive symptoms and craving depends on the level of a moderating variable (intervention condition). In other words, the mediating (i.e., indirect) effect of craving in predicting substance use is conditional on the interaction between intervention condition and depression (Morgan-Lopez & MacKinnon, 2006; Preacher et al. 2007). As described above, models were estimated using FIML with 1000 bootstrap draws to obtain standard errors for the indirect effect. For the moderation tests f2 was used as an estimate of the effect size, which is the proportion of variance explained by the interaction relative to the unexplained variance in the criterion (see Aiken & West, 1991). Unfortunately, there is much less research on effect size measures for moderated mediation (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009). For the current study, we calculated the effect size for the moderated mediation effect using the proportion of variance explained by the moderated mediation effect divided by the total proportion of variance explained (MacKinnon, 2008).

Figure 2.

a. Hypothesized moderation effect.

b. Moderated-mediation model with non-significant paths indicated by gray dashed lines and significant paths indicated by black solid lines.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation coefficients for all measured variables in the analyses are shown in Table 1. A series of χ2 tests and t-tests were conducted to determine whether there were any significant differences between the intervention groups at baseline. Results indicated a significant difference on racial distribution between the groups, χ2 (1, N=168) = 5.51, p = 0.02, such that the MBRP group consisted of a higher proportion of White participants (63%, n=59) than the TAU group (45%, n=34). This difference was a non-systematic effect of randomization, and there were no differences in attrition between White and non-White participants in the MBRP group χ2 (1, N=93) = 0.631, p = 0.43. There were no other baseline intervention differences on key demographic or main outcome variables (all ps > 0.14).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for primary study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | MBRP Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BDI baseline | -- | .69** | .19 | .11 | −.06 | −.21 | 13.07 (9.56) |

| 2. BDI postintervention | .82** | -- | .16 | .12 | −.11 | −.19 | 12.16 (12.37) |

| 3. PACS baseline | .28* | .29 | -- | .40** | −.046 | −.07 | 1.55 (1.13) |

| 4. PACS two months | .43** | .54** | .18 | -- | .08 | .46* | 0.98 (0.98) |

| 5. Treatment hours received | −.003 | −.02 | .19 | −.20 | -- | −.05 | 12.79 (4.91) |

| 6. AODD 4-months post | .08 | .53* | .14 | .73** | −.52** | -- | 5.62 (14.33) |

| TAU Mean (SD) | 14.80 (12.94) | 14.21 (13.84) | 1.73 (1.42) | 1.42 (1.49) | 9.75 (8.16) | 9.33 (20.80) |

Note. TAU = treatment-as-usual below the diagonal; MBRP = Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention above the diagonal; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; PACS = Penn Alcohol Craving Scale; AODD = alcohol or other drug use days; SD = standard deviation. Means are based on untransformed variables.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

MBRP participants attended an average of 65% of intervention sessions, or 10.36 (SD = 4.83) hours of treatment, across the eight weeks. The majority (86%) reported practicing meditation at postintervention (for an average of 2.60 (SD = 1.45) per week hours), and 54% reported continued practicing through four months postintervention (for an average of 2.18 (SD = 1.80) hours per week). TAU participants reported an average of 9.75 (SD = 8.17) hours of treatment, which was significantly less (p = 0.006) than the total number of treatment hours received by the MBRP group (M = 12.79 (SD = 4.91)). Two-thirds of participants (N = 103; MBRP n = 62, TAU n = 41) completed the postintervention assessment, 57% (N = 95; MBRP n = 53; TAU n = 42) completed the two-month follow-up, and 73% (N = 122; MBRP n = 70; TAU n = 52) completed the four-month follow-up. No significant differences in rates of attrition between groups were found at postintervention, (χ2 (1, N=168) = 1.663, p = 0.20); two months (χ2 (1, N=168) =1.514, p = 0.22); or four months (χ2 (1, N=168) =0.012, p = 0.91).

As seen in Table 1, mean depression scores in both conditions and at both baseline and postintervention were in the mild range. Scores were lower for the MBRP group as compared to TAU at baseline and postintervention, however these differences were not significant (p > 0.33). Likewise, the MBRP group had lower craving scores (at baseline and postintervention) and had fewer days of use four months postintervention, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (p < 0.05) in independent samples t-tests. It is important to note the low average days of use over the 60 day period (9.33 days for TAU, 5.62 days for MBRP) and the large standard deviations for both groups. Across both groups, fewer than 30% of participants (29.1% in TAU, 28.6% in MBRP) had any days of use. Of those who used, 28.6% and 33.3% of TAU and MBRP participants, respectively, only used substances on one day during the 60-day follow-up period.

For purposes of the current study, it was useful to examine the different patterns of correlations across groups. Below the diagonal correlations indicated that participants in TAU evinced strong associations between postintervention BDI, two-month craving and days of use four months postintervention. Above the diagonal correlations indicated that among MBRP participants postintervention BDI was not significantly correlated with two month craving or days of use four months postintervention.

Path Models

The first goal of the current study was to examine the association between post-intervention depression symptoms, craving two months following the intervention, and substance use four months following the intervention. These time points were chosen to establish temporal precedence between measures of depressive symptoms and both the mediator (craving) and the outcome (substance use). To examine these associations, we started by assessing the direct effect of intervention on postintervention depression scores, craving scores two months following intervention, and days of substance use four months following the intervention, while controlling for treatment hours, gender, race, and baseline levels of substance use, craving and depression scores. The direct effect of intervention in predicting days of use at the four month follow-up was not significant (β = 0.24, p = 0.06)2, however several hypothesized relations between intervention assignment, depressive symptoms, craving and days of use were supported. Significant effects were observed for the regression of days of use on craving at two-month follow-up (β = 0.65, p < 0.01), BDI scores postintervention (β = −0.28, p = 0.02) and total treatment hours (β = −0.32, p = 0.02). Craving at two-month follow-up was significantly predicted from intervention assignment (β = −0.20, p = 0.03) and postintervention depression scores (β = 0.32, p < 0.01). Postintervention levels of depression were significantly related to baseline levels (β = 0.72, p < 0.01), but were not significantly related to intervention assignment (β = −0.06 p > 0.05) or baseline craving (β = 0.02, p = 0.76). Thus, craving and postintervention depression predicted total days of use, and both intervention assignment and postintervention levels of depression were significantly related to craving. Gender and race were not significantly related to days of use, postintervention depression scores, or craving (p > 0.05). Also, total treatment hours were not significantly related to postintervention depression scores or craving (p > 0.05).

Mediation Models

In order to examine the potential mechanisms underlying the relations between intervention, depressive symptoms, craving and days of use; we investigated whether craving at two months postintervention mediated the relation between postintervention depressive symptoms and days of use at four months postintervention3. Baseline levels of craving, depressive symptoms and days of use, gender, race, and treatment hours were included as covariates. This model provided an excellent fit to the observed data (χ2 (8) = 12.21, p = 0.14; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.04). As shown in Table 2, results indicated that craving scores significantly mediated the relation between postintervention depressive symptoms in the prediction of days of use over the four months following the intervention (Indirect effect = 0.23 (95% C.I.: 0.08 – 0.40), p = 0.01 proportion mediated = 0.07). The mediation model explained 40% of the variance in postintervention days of use, assessed at four months.

Table 2.

Results from mediation analyses

| Path | Direct and Indirect Effects | β | B (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days of use on gender (Female = 1) | 0.13 | 4.75(−4.39 – 12.93) | |

| Days of use on race (White = 1) | −0.16 | −5.21 (−15.99 – 1.42) | |

| Days of use on treatment hours | −0.30 | −0.74 (−1.69 – −0.04) | |

| Days of use on baseline days of use | −0.17 | −0.12 (−0.35 – 0.07) | |

| PACS two months on PACS baseline | 0.21 | 0.22 (0.06 – 0.39)* | |

| BDI postintervention on BDI baseline | 0.74 | 0.84 (0.71 – 0.95)** | |

| b | Days of use on PACS two months | 0.57 | 7.45 (3.14 – 11.10)** |

| c1 | Days of use on BDI postintervention | −0.28 | −0.29 (−0.70 – 0.03) |

| c2 | Days of use on intervention (TAU = 0; MBRP = 1) | 0.18 | 5.93 (−1.42 – 14.40) |

| a1 | PACS two months on BDI postintervention | 0.30 | 0.03 (0.01 – 0.05)* |

| a2 | PACS two months on group (TAU = 0; MBRP = 1) | −0.17 | −0.44 (−0.90 – −0.08)* |

| a1*b | Indirect effect: Days of use on BDI via PACS | 0.12 | 0.23 (0.08 – 0.40)* |

| a2*b | Indirect effect: Days of use on group via PACS | −0.24 | −3.24 (−6.99– −0.46)** |

Note. (n = 168); Days of use = Alcohol or other drug use days over the four months following intervention; TAU = treatment as usual; MBRP = mindfulness-based relapse prevention; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; PACS = Penn Alcohol Craving Scale scores.

p < .05;

p < .01

Moderation Models

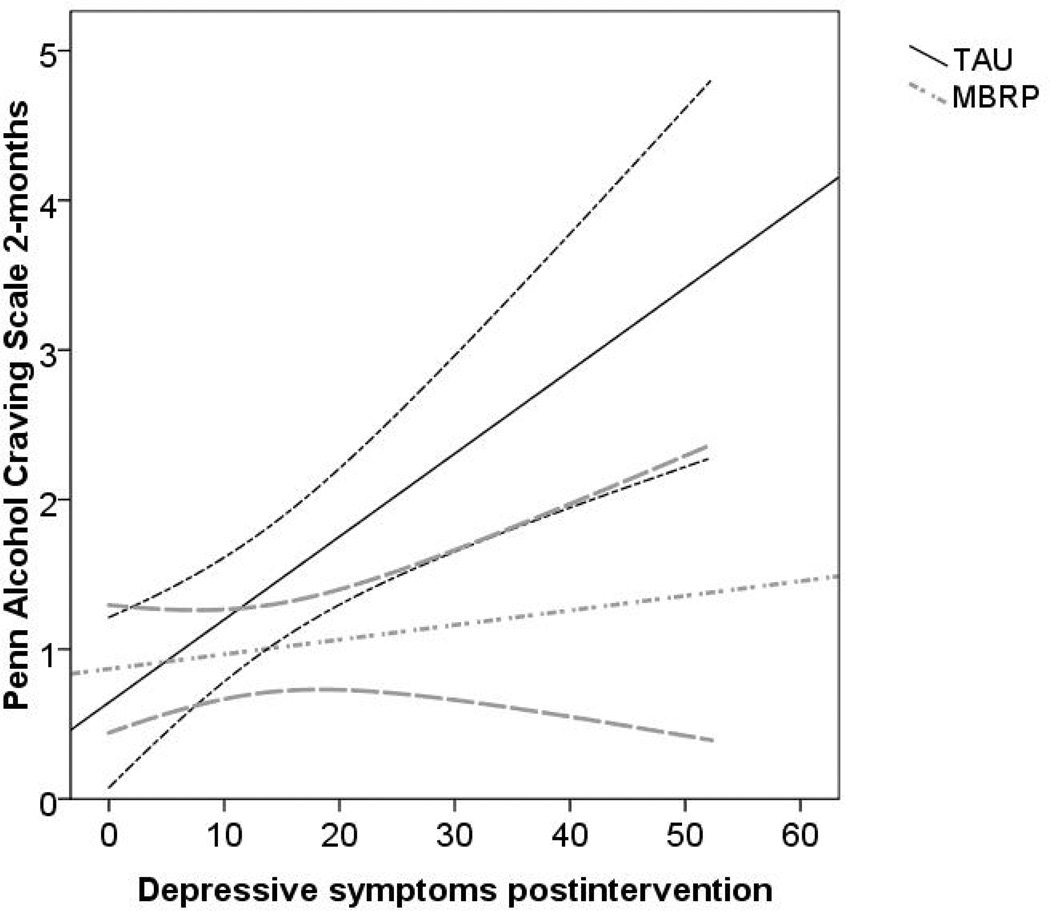

Moderated regression analyses were conducted to examine whether there was an interaction between depressive symptoms and intervention in the prediction of craving following the intervention. There was a significant moderation effect for the relation between intervention assignment, depression scores at postintervention and craving scores at two months (β = −0.32, p = 0.001, f2 = 0.21). As shown in Figure 3, probing the moderation effect indicated that individuals who were randomly assigned to MBRP did not evince the strong, positive association between depression scores and craving scores that was present for the TAU participants.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of depression by intervention predicting craving with 95% confidence bands (n = 140).

Moderated Mediation Models

The final hypothesis, that the attenuation of the relation between depression and craving among MBRP participants explained postintervention substance use, was examined using moderated mediation analyses. The goal of this analysis was to test the significance of the product of the a3-path and the b-path in Figure 2b. As seen in Table 3, the indirect effect of craving in the analysis of postintervention days of use regressed on the depression-by-intervention interaction was significant, providing evidence for moderated mediation (Indirect effect = −0.06 (95% C.I.: −0.13 - −0.01), proportion mediated =0.07, f2 = 0.18) with the moderated mediation model explaining 50% of the variance in days of use at four months postintervention.

Table 3.

Results from moderated mediation analyses

| Path | β | B (95% C.I.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | PACS two months on BDI postintervention | 0.49 | 0.05 (0.01 – 0.09)* |

| a2 | PACS two months on group (TAU=0; MBRP=1) | −0.20 | −0.53 (−1.01 – −0.07)* |

| a3 | PACS two months on group × BDI postintervention | −0.27 | −0.05 (−0.09 – −0.01)* |

| b | Days of use on PACS two months | 0.71 | 1.23 (0.52 – 2.17)** |

| c1 | Days of use on BDI postintervention | −0.43 | −0.08 (−0.25 – 0.15) |

| c2 | Days of use on group (TAU = 0; MBRP = 1) | 0.27 | 1.28 (−0.39 – 2.98) |

| c3 | Days of use on group × BDI postintervention | 0.12 | 0.04 (−0.16 – 0.20) |

| a1*b | Indirect effect: Days of use on BDI via PACS | 0.35 | 0.06 (0.01 – 0.14)* |

| a2*b | Indirect effect: Days of use on group via PACS | −0.51 | −0.65 (−1.45 – −0.07)* |

| a3*b | Indirect effect: Days of use on group × BDI via PACS | −0.44 | −0.06 (−0.13 – −0.01)* |

Note. (n = 168); Days of use = Alcohol or other drug use days over the four months following intervention; TAU = treatment as usual; MBRP = mindfulness-based relapse prevention; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; PACS = Penn Alcohol Craving Scale.

p < .05;

p < .01

This finding can be further broken down by examining the indirect effect of craving in the association between levels of depression and days of use for each intervention group separately. The indirect effect approached significance for the TAU group (indirect effect = 0.05 (95% C.I.: −0.02 – 0.09), p = 0.05, proportion mediated = 0.18), but not for the MBRP group (indirect effect = 0.005 (95% C.I.: −0.02 – 0.03), p = 0.65, proportion mediated = 0.002). Therefore craving partially mediated the relation between depressive symptoms and substance use for TAU, but not for MBRP participants.

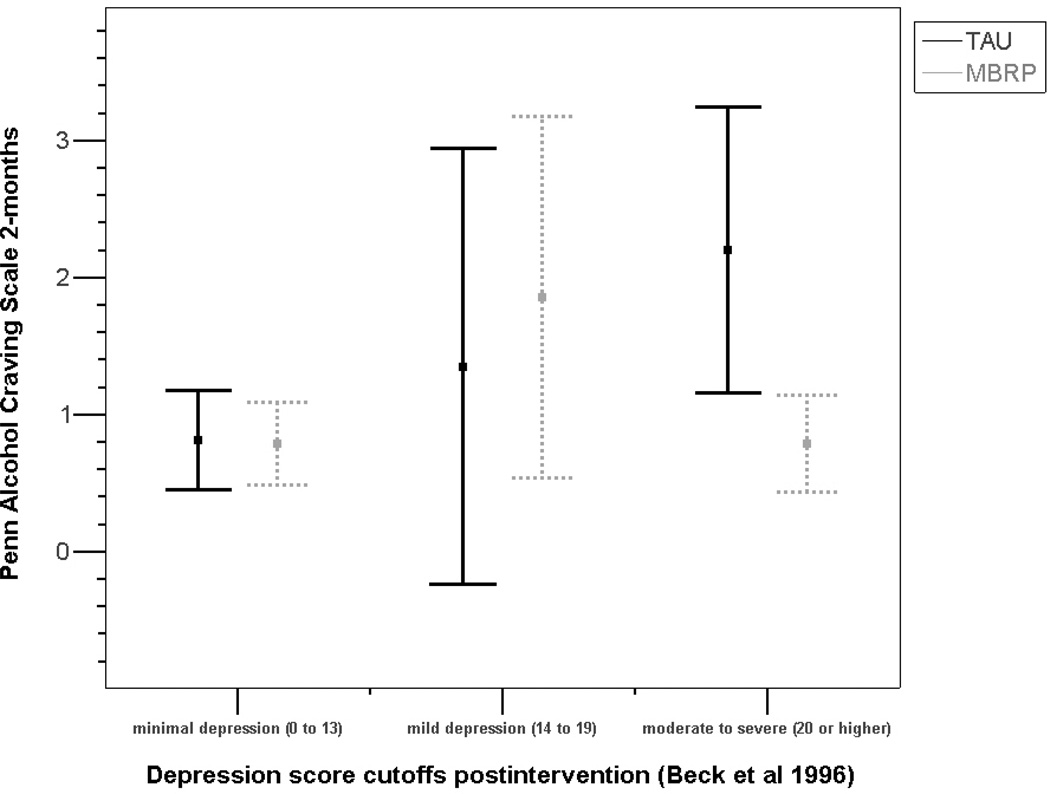

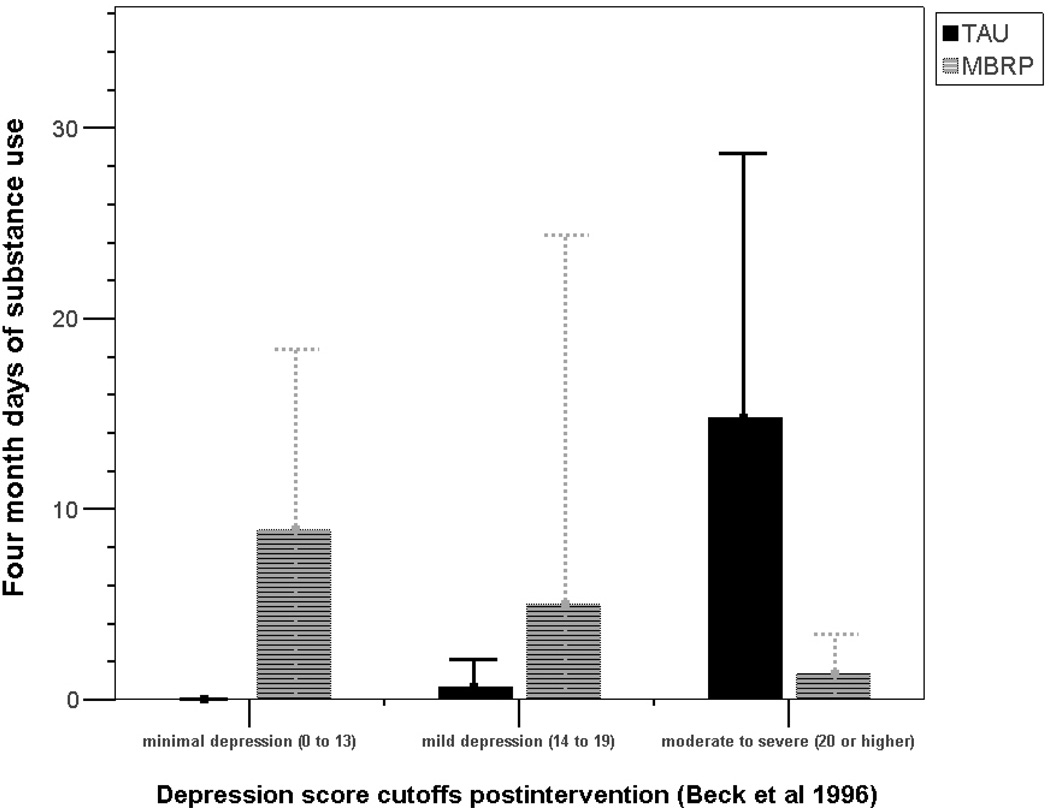

Given the complexity of moderated mediation effects it is often helpful to examine these effects using a variety of plotting techniques (e.g., simple slopes, creating cutoff scores, etc.). As seen in Figures 4a and 4b, individuals with the highest level of depressive symptoms (BDI scores greater than 20) in MBRP had significantly lower craving scores and significantly fewer days of use, as compared to the TAU participants with higher depressive symptoms. Figure 4a suggests craving increased proportional to increasing levels of depressive symptoms for TAU participants, but not for MBRP participants. Figure 4b shows participants in TAU had the most substance use days at the highest level of depressive symptoms, whereas participants in MBRP had few substance use days at the highest levels of depressive symptoms and more substance use days at low levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 4.

a. Craving scores by level of depression and intervention group (n = 140).

b. Days of use by level of depression and intervention group (n = 140).

Discussion

Results from the current study supported all four study hypotheses. First, positive relations were supported between postintervention depressive symptoms, craving at the two-month follow-up, and days of alcohol or other drug use over the four-month follow-up period. Second, results from mediation analyses supported the hypothesis that craving significantly mediated the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol or drug use days following intervention. Thus, the relation between depressive symptoms and intervention outcomes can be partially explained by craving. Third, moderation analyses indicated that depressive symptoms moderated the relation between intervention assignment and craving, such that individuals in MBRP showed virtually no association between depressive symptoms and craving while individuals in TAU evinced a strong association between depressive symptoms and craving. Finally, moderated mediation analyses showed an interaction between depressive symptoms and intervention assignment in the prediction of craving and subsequent substance use, indicating that the relation between depressive symptoms and postintervention days of use was mediated by craving among the TAU participants, but not among those in the MBRP group.

Further evaluation of the moderated mediation effect, shown in Figure 4b, suggested a potential disordinal interaction between intervention group and depressive symptoms in prediction of substance use days: individuals with more depressive symptoms used substances on fewer days if they were in the MBRP condition, as compared to the TAU condition, whereas individuals with minimal or mild depressive symptoms used substances on more days if they were in the MBRP condition, as compared to the TAU condition. Supplementary analyses controlling for meditation practice four months postintervention indicated that all of the MBRP participants who continued meditation practice (n = 46, 63% of MBRP participants) were abstinent (i.e., zero days of use) four months following the intervention, regardless of depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that the practice of mindfulness meditation is associated with lower risk for substance use relapse; however, a causal relation has not been established.

The moderation and moderated mediation effects observed in the current study are consistent with the purpose and hypothesized mechanisms of MBRP. The mindfulness practices employed in the course are designed to help clients increase awareness of and change the relation to challenging situations, including negative emotional states, without “automatically” or habitually reacting, thereby effectively altering the conditioned response of drug craving in response to negative affect. In combination with findings from other mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions (e.g., Dahl, Wilson, & Nilsson, 2004; Gifford et al., 2004; Hayes et al., 1999; Levitt, Brown, Orsillo, & Barlow, 2004), the current data suggest these interventions may be effective in helping clients successfully modify responses to challenging or aversive internal experience. Similar to the work of Teasdale and colleagues (Teasdale et al., 2000) the current sample reported subclinical depression scores and treatment focused on recognition of these more subtle states before they trigger full blown depressive or substance use relapse. Importantly, the levels of depressive symptoms across intervention groups did not differ, thus it may be the reaction to the experience of negative emotional states, rather than the emotional states themselves, that are problematic. Furthermore, mindfulness-based treatment may help interrupt the repeated association of subclinical depressive thinking or symptomatology with affective or cognitive aspects of craving that perpetuate the relapse cycle.

Drawing from neurobiological data and the neuroimaging literature, there are several plausible mechanisms by which MBRP might be affecting the relation between depressive symptoms and craving. Areas of the brain that have been associated with both substance use disorders and depression, including the anterior cingulated cortex, prefrontal cortex (dorsolateral, ventromedial and medial), amygdala and subareas of the insula, have also been shown to be affected by mindfulness training (Lutz, Brefczynski-Lewis, Johnsone, & Davidson, 2008). Bonson and colleagues (2002) found deactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex in cocaine abusers during exposure to cocaine cues that elicited craving; while Hölzel and colleagues (2008) found that experienced meditators, in comparison to non-meditators, showed increased activation in the medial prefrontal cortex during a mindful breathing exercise. While the neurobiological investigation of meditation is relatively young, data point to common neural substrates implicated in substance use and affective disorders that may also be affected by meditation (Brewer, Smith, Bowen, Marlatt, & Potenza, in press) and combining MBRP with medication that further regulates neurotransmitter functioning could produce even stronger effects and more relief from craving.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study are worth noting. The most significant design limitation is the brevity of the postintervention follow-up period. The majority (75.6%) of participants for whom follow up data were available were abstinent at the four-month follow-up, and information on differences between intervention groups in abstinence rates beyond that four-month window were not available in the study. Future research with a more extensive follow-up period is clearly needed. The rates of substance use across intervention groups indicated significant differences during the intervention (η2 = 0.09) and two months following the intervention (η2 = 0.04), however these effects were not maintained at the four-month follow-up (η2 = 0.02). We have hypothesized that the lack of ongoing meditation support (e.g., mindfulness “sitting” groups) following the intervention resulted in the attenuation of MBRP effects (Bowen, Chawla, Collins, et al., 2009) and this is an important area for future research. It also suggests that a brief mindfulness intervention without continued support might not be sufficient for maintaining long-term change. Missing data at follow-up assessment points is another serious limitation. Although studies of similarly severe populations evince similar attrition rates (Edwards & Rollnick, 1997), this shortcoming merits concern, and of note, the 75.6% abstinence rate reflects only those participants who were successfully followed. It is important to note that more than half of participants in both groups (62.7% of TAU, 52.8% of MBRP) were court mandated to treatment or had some level of legal involvement related to substance use, thus the low rates of substance use in this sample could be reflective of mandatory drug testing during the follow-up period. Court/legal involvement was not significantly different between groups (χ2 (1) = 0.25, p =0.29), nonetheless the rates of abstinence in the current study might not generalize to non-mandated treatment populations.

Measurement issues in the current study raise additional concern. The use of retrospective, self-reported days of use is one potential limitation, although self-reported alcohol and other drug use has been shown to be relatively reliable and valid (e.g., Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & Del Boca, 2000). The subjective, self-report measurement of craving is also problematic (Drummond, Litten, Lowman, & Hunt, 2000) and future studies would benefit from implicit, physiological and neurobiological measures of craving to further assess the relations observed in the current study. Finally, as noted above, the measure of mindfulness skills included in the main outcomes trial did not mediate the relation between intervention group and substance use outcomes (Bowen, Chawla, Collins, et al., 2009). Analyses also indicated that increased mindfulness skills did not relate to changes in depressive symptoms or craving, thus the findings in the current study cannot be explained by changes in mindfulness as measured by the Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire. Alternative measures of mindfulness or other related constructs may help future studies better identify specific mechanisms of MBRP.

Another potential confound is the disparate levels of training of the therapists, with those facilitating MBRP having higher levels of education than those in TAU. While previous research has generally indicated therapist’s level of training is unrelated to substance use outcomes (see Najavits & Weiss, 1994), it is nonetheless important to consider that some of the effects of MBRP could be explained by the qualitative differences between the MBRP therapists (mostly Master’s level) and the TAU counselors (mostly Chemical Dependency Counselors). The difference between groups in number of treatment hours per week, although covaried in all analyses, also presents a potential confound. Preliminary analyses indicated treatment hours were not strongly associated with outcomes, however future research should examine whether providing the same amount of treatment to both TAU and MBRP changes the outcomes. Similarly, there were different structures of the treatments; MBRP was delivered in closed cohorts, while TAU was administered in a rolling-admission structure, thus allowing potential non-independence of individual outcomes in the MBRP group. It could be the case that alliance between participants within a closed cohort group could explain the difference in outcomes between MBRP and TAU, particularly with respect to psychological distress (Gillaspy, Wright, Campbell, Stokes, & Adinoff, 2002). In addition, the therapists, participants and graduate research assistants were not blind to intervention group assignment. However, it would not be possible to blind the therapists or the participants because of the nature of the intervention. With respect to the research assistants, all assessments were conducted online, reducing the likelihood of biases due to non-blinding.

A final consideration is that testing moderated mediation is a relatively new area of quantitative inquiry. Although we have conducted analyses using the best practices described by recent quantitative studies (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009; MacKinnon, 2008; Morgan-Lopez & MacKinnon, 2006; Preacher et al., 2007), replication of the current findings is necessary. The small sample size yielded sufficient power to detect effects and the sample size to model parameters ratio was 9:1 for the mediation analysis (8:1 for the moderated mediated analysis), which is greater than the minimum 5:1 ratio (Bentler & Chou, 1987). Nonetheless, the results should be considered preliminary until replicated in subsequent studies with larger samples. Likewise, a more stringent test of the mediation effect would have controlled for posttreatment days of use prior to the measurement of craving in the prediction of days of use following the measurement of the mediator (MacKinnon, 2008). Finally, the current study compared MBRP to an active treatment control group, but did not provide a test of whether MBRP differed from other empirically supported active treatments (e.g., relapse prevention or coping skills training).

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Although direct effects of treatment on substance use outcomes evident at the two-month follow-up assessment were not evident at four months, data from the current study offer some preliminary empirical support for the benefits of integrating mindfulness training with relapse prevention treatment and identify one potential mechanism of change following MBRP. The racial diversity (only 53.6% of participants were White) and severity of the sample (41.3% unemployed, 19% polysubstance abusers) suggest these findings will generalize to a wide group of substance users. The current study specifically examined one potential mechanism by which practicing mindfulness skills may lead to reductions in substance use following intervention. The results suggest that mindfulness training might help clients by attenuating the relation between negative cognitive and emotional states and subjective experiences of craving. While there are a multitude of studies on the roles of negative affect and craving in the relapse process, the current study provides a novel examination of the mediating role of the relation between depressive symptoms and craving, which has received less attention in the research literature. Although future studies will be needed to determine the treatment’s effectiveness and mechanisms of action, the results suggest that incorporating mindfulness training as part of substance use treatment (either as the eight-week MBRP course or as an additive component to another existing treatment) could help clients cope more effectively with affective discomfort during early abstinence. Future studies would benefit from additional and varied measures of these factors and interrelations, such as physiological measures of affect and craving, and functional imaging techniques identifying neurocorrelates of these processes. Additionally, studies of related behaviors, such as pathological gambling and binge eating, could shed light on a potentially common role of the relation between negative affective states and craving across a broader class of addictive behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse: R21 DA010562 (Marlatt, PI).

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. G. Alan Marlatt for his leadership and support, and the Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention research team for their dedication to this project. Without these efforts and talents, this project would not have been possible.

Footnotes

It is important to note that we are testing the interaction between intervention and depression, thus in the analyses neither intervention nor depression is specifically designated as the moderator. Given that probing moderation effects is often easier with categorical variables we indicate intervention as the moderator, but it is the interaction between depression and intervention that defines the moderating effect.

The non-significant direct effect of intervention on four-month days of use in the current study was inconsistent with the significant main effect of the MBRP intervention on substance use found in the main outcomes study (Bowen, Chawla, Collins et al., 2009) for two reasons. First, the current study only evaluated days of use at the four month follow-up, whereas the main outcomes study evaluated the effect of MBRP across the entire four month follow-up. The differences between days of use for the MBRP and TAU groups were larger at the two month follow-up [TAU average days of use = 5.32 (SD=14.67) and MBRP average days of use 1.59 (SD=5.94)] than the four month follow-up [TAU average days of use = 9.33 (SD=20.80) and MBRP average days of use 5.62 (SD=14.33)]. Second, the main outcomes study used generalized estimating equations to estimate the time by treatment effect, whereas the current study evaluated the direct effect of intervention at a single point in time.

Ideally, in testing mediation it is important to control for posttreatment changes in the dependent variable that might have occurred prior to the posttreatment changes in the hypothesized mediator. In the current study we could not control for days of use at two months because of unequal variances between groups at the two month follow-up (Levene’s test: F (1, 122) = 15.15, p < 0.005), as well as significant differences in the correlations between two month and four month days of use between intervention groups (TAU r = .84, p < 0.005; MBRP r = .08, p = .61). Thus, including the days of use at two months would have violated the homoscedasticity and serial independence assumptions of regression, respectively.

Contributor Information

Katie Witkiewitz, Washington State University - Vancouver.

Sarah Bowen, University of Washington.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Feinn R, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. The effects of naltrexone on alcohol consumption and affect reactivity to daily interpersonal events among heavy drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:199–208. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton R, Del Boca F. Talk is cheap: measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Smith GT, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;11:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Chou CH. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research. 1987;16:78–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bonson KR, Grant SJ, Contoreggi CS, Links JM, Metcalfe J, Weyl HL, et al. Neural systems and cue-induced cocaine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:376–386. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Hsu S, Grow J, et al. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A Pilot Efficacy Trial. Substance Abuse. 2009:295–305. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, Marlatt G. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A clinician’s guide. NY: Guilford Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Smith JT, Bowen S, Marlatt GA, Potenza MN. Applying Mindfulness-Based Treatments to Co-Occurring Disorders: What Can We Learn from the Brain? Addiction. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02890.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Lam CY, Robinson JD, Paris MM, Waters AJ, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Real-time craving and mood assessments before and after smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1165–1169. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, Collins SE, Bowen S, Hsu S, Grow J, Douglass A, Marlatt GA. The Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention Adherence and Competence Scale: Development, Interrater Reliability and Validity. Psychotherapy Research. doi: 10.1080/10503300903544257. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Zywiak WH. Understanding relapse in the broader context of post-treatment functioning. Addiction. 1996;91:S173–S189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Sorensen S, Leonard KE. Initial depression and subsequent drinking during alcoholism treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:401–406. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Litt MD, Morse PA, Bauer LO, Gaupp L. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative-mood reactivity, and relapse in treated alcoholic men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:243–250. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Maisto SA, Martin CS, Bukstein OG, Salloum IM, Daley DC, et al. Major depression associated with earlier alcohol relapse in treated teens with AUD. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Booth BM, Kirchner JE, Deneke DE. Recognition and management of depression in a substance use disorder treatment population. The Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:563–569. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Flynn HA, Kirchner J, Booth BM. Depression after alcohol treatment as a risk factor for relapse among male veterans. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19:259–265. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J, Wilson KG, Nilsson A. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Treatment of Persons at Risk for Long-Term Disability Resulting From Stress and Pain Symptoms: A Preliminary Randomized Trial. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:785–801. [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, Marlatt GA. Overcoming Your Drug or Alcohol Problem: Effective Recovery Strategies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Litten RZ, Lowman C, Hunt WA. Craving research: future directions. Addiction. 2000;95:247–255. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AG, Rollnick S. Outcome studies of brief alcohol intervention in general practice: the problem of lost subjects. Addiction. 1997;92:1699–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science. 2009;10:87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen-Hall ML, et al. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:689–705. [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy JA, Jr, Wright AR, Campbell C, Stokes S, Adinoff B. Group alliance and cohesion as predictors of drug and alcohol abuse treatment outcomes. Psychotherapy Research. 2002;12:213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SM, Sterling R, Siatkowski C, Raively K, Weinstein S, Hill PC. Inpatient desire to drink as a predictor of relapse to alcohol use following treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:242–245. doi: 10.1080/10550490600626556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski TT. The Gorski-Cenaps Model for Recovery and Rrelapse Prevention. Missouri: Herald House/Independence Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vagge LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, et al. The effect of depression on returning to drinking: A prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:259–265. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz DT, Frederick-Osborne SL, Galloway GP. Craving predicts use during treatment for methamphetamine dependence: A prospective, repeated-measures, within-subject analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. Major depression in 6050 former drinkers: Association with past alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:794–800. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Bissett RT, Korn Z, Zettle RD, Rosenfarb IS, Cooper LD, et al. The impact of acceptance versus control rationales on pain tolerance. The Psychological Record. 1999;49:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N, Armstrong S. Prospective and retrospective reports of mood states before relapse to substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:400–407. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Ott U, Gard T, Hempel H, Weygandt M, Morgen K, Vaitl D. Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2008;3:55–61. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper JW, Su Z, Looby AR, Ryan ET, Penetar DM, Palmer CM, Lukas SE. Incidence and patterns of polydrug use and craving for ecstasy in regular ecstasy users: An ecological momentary assessment study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kodl MM, Fu SS, Willenbring ML, Gravely A, Nelson DB, Joseph AM. The impact of depressive symptoms on alcohol and cigarette consumption following treatment for alcohol and nicotine dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:92–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Wilkinson DA. Use and misuse of the concept of craving by alcohol, tobacco, and drug researchers. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner A. Science-based views of drug addiction and its treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1314–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JT, Brown TA, Orsillo SM, Barlow DH. The effects of acceptance versus suppression of emotion on subjective and psychophysiological response to carbon dioxide challenge in patients with panic disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:747–766. [Google Scholar]

- Levy MS. Listening to our clients: The prevention of relapse. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:167–172. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile B. Twelve Step programs: An update. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2003;2:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig AM, Wikler A. "Craving" and relapse to drink. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1974;35:108–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Johnsone T, Davidson RJ. Voluntary regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of expertise. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001897. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:31–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test the significance of the mediated effect. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia KV. Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika. 1970;36:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J, Marlatt GA. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between Internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) In: Mattson ME, editor. Project MATCH Monograph Series Vol. 4. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Mueller TI, et al. Naltrexone and cue exposure with coping and communication skills training for alcoholics: treatment process and 1-year outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1634–1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Lopez AA, MacKinnon DP. Demonstration and evaluation of a method for assessing mediated moderation. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38(1):77–87. doi: 10.3758/bf03192752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD. Variations in therapist effectiveness in the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: An empirical review. Addiction. 1994;89:679–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Ciccocioppo M, Conklin CA, Milanak M, Grottenthaler A, Sayette M. Mood influences on acute smoking responses are independent of nicotine intake and dose expectancy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:79–93. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE. Increased desire to smoke during acute stress. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1037–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker D, Hayes AF. Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K, Baillie A, Reid S, Morley K, Teesson M, Sannibale C, et al. Do acamprosate or naltrexone have an effect on daily drinking by reducing craving for alcohol? Addiction. 2008;103:953–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Teasdale JD, Williams JM. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Theoretical rationale and empirical status. In: Hayes S, Follette VM, Linehan MM, editors. Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ. Negative affect and smoking lapses: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:192–201. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis M, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, O’Malley SS. Craving for alcohol: Findings from the clinic and the laboratory. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34:223–230. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon RL, Corbit JD. An opponent-process theory of motivation: I. Temporal dynamics of affect. Psychological Review. 1974;81:119–145. doi: 10.1037/h0036128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Cavalieri TA, Leonard DM, Beck AT. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory for primary care to screen for major depression disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1999;21:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: the neurobiology of drug- and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2000;25:125–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory-second edition in a sample of college students. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;19:187–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Williams JMG, Soulsbay JM, Segal ZV, Ridgeway VA, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:615–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Markou A, Lorang MT, Koob GF. Basal extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus acumbens are decreased during cocaine withdrawal after unlimited-access self-administration. Brain Research. 1992;593:314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91327-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler RA, Twining RC, Jones JL, Slater JM, Grigson PS, Carelli RM, et al. Behavioral and electrophysiological indices of negative affect predict cocaine self-administration. Neuron. 2008;13:774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikler A. Recent progress in research on the neurophysiologic basis of morphine addiction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1948;105:329–338. doi: 10.1176/ajp.105.5.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was zen, this is tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, Walker DD. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol use disorders: The meditative tortoise wins the race. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;19:211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Villarroel N. Dynamic association between negative affect and alcohol lapses following alcohol treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:633–644. doi: 10.1037/a0015647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman ML, Tavares H, Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N. The impact of gender, depression, and personality on craving. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2007;26:79–84. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]