ABSTRACT

Purpose: This qualitative study sought to explore older people's experience of ageing with multiple sclerosis (MS) and to describe the natural history of self-management from their points of view. Methods: Eighteen people over age 55 and living with MS for at least 20 years were recruited from an MS clinic and rehabilitation outpatient records. Interviews (60–80 min), using open-ended questions, explored participants' lifelong experiences of MS. Following interview transcription, data were coded and analyzed; themes, subthemes, and their relationships were described based on consensus. Results: Participants recounted their diagnosis process, their life experience with MS, and how they eventually accepted their disease, adapted, and moved toward self-management. The findings included vivid descriptions of social relationships, health care interactions, overcoming barriers, and the emotions associated with living with MS. A conceptual model of phases of self-management, from diagnosis to integration of MS into a sense of self, was developed. Conclusions: Study participants valued self-management and described its phases, facilitators, and inhibitors from their points of view. Over years and decades, learning from life experiences, trial and error, and interactions with health care professionals, participants seemed to consolidate MS into their sense of self. Self-determination, social support, strong problem-solving abilities, and collaborative relationships with health professionals aided adaptation and coping. Findings from this study make initial steps toward understanding how MS self-management evolves over the life course and how self-management programmes can help people with MS begin to manage wellness earlier in their lives.

Key Words: aged; chronic disease; adaptation, psychological; quality of life; self care; multiple sclerosis

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Cette étude qualitative visait à analyser l'expérience du vieillissement chez les aînés atteints de sclérose en plaques (SP) et à décrire le parcours naturel de leur autogestion des soins en se basant sur leurs propres points de vue. Méthode : Un échantillon de 18 personnes de 55 ans et plus, vivant depuis au moins 20 ans avec la SP, a été recruté dans des cliniques de SP et à partir de dossiers de patients externes en réadaptation. Des entrevues de 60 à 80 minutes ont été réalisées avec des questions ouvertes, qui ont permis aux participants de parler de leur expérience de vivre avec la SP. Une fois les entrevues transcrites, les données recueillies ont été codées et analysées; les thèmes, les sous-thèmes et leurs relations ont été décrits en se basant sur une formule de consensus. Résultats : Les participants ont raconté la façon dont ils ont reçu leur diagnostic et comment, à la longue, ils avaient fini par accepter leur maladie, s'y étaient adaptés et étaient graduellement passés à une autogestion de leurs soins. Les conclusions regroupaient des descriptions vivantes des relations sociales, des interactions en soins de santé, des obstacles et de la façon de les surmonter ainsi que des émotions associées avec le fait de vivre avec la SP. Un modèle conceptuel des phases d'autogestion des soins, du diagnostic jusqu'à l'intégration de la SP à la conscience de soi, a été élaboré. Conclusions : Les participants à l'étude avaient à cœur l'autogestion de leurs soins et en ont décrit les étapes, les éléments facilitateurs et les obstacles selon leur point de vue. Avec les années et les décennies, les apprentissages issus de l'expérience de vie, les essais et les erreurs et l'interaction avec des professionnels de la santé, les participants semblent avoir intégré la SP et la considèrent comme faisant partie d'eux-mêmes. L'autodétermination, le soutien social, de bonnes capacités à résoudre les problèmes et des relations fondées sur la collaboration avec des professionnels de la santé ont contribué à leur adaptation et les ont aidés à faire face à leur maladie. Les conclusions de cette étude marquent les premiers jalons vers une meilleure compréhension de l'autogestion de la SP et de son évolution au fil de l'existence, de même que de la façon dont les programmes d'autogestion peuvent aider les personnes aux prises avec la SP à prendre leur bien-être en charge tôt dans leur vie.

Mots clés : autogestion des soins, habiletés d'adaptation, maladie chronique, qualité de vie, vieillissement

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common progressive neurological disease, usually diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 40 years and affecting women more than men.1 For most people, the course of MS is characterized by uncertain and unpredictable relapsing and remitting episodes affecting vision, sensation, balance, and movement.2 About 15 years after diagnosis, the course usually becomes chronically progressive; most people will become dependent on mobility aids after about 20 years.2,3 In MS clinics, one of the most important questions patients ask is, “What should I expect in the future, and how will the disease progress?” Although initial severity of disease predicts how quickly someone will develop walking impairment,4 once this level of limitation is reached, disease variables are no longer predictive of disease progression;2,5 that is, early predictors of disease progression, such as severity, do not predict how a person with MS will function in the long term. Recent evidence suggests that intra-individual factors such as age, exercise adherence, attitude, and comorbid conditions, and extra-individual factors such as social support and financial resources, influence development of functional limitation and quality of life.6,7 Immune-modulating drugs decrease the frequency and severity of MS attacks and reduce the number of MS lesions in the brain, and several have been shown to slow the progression of disability.8 Some people with MS have learned to cope with this lifelong disease and live well into their seventies and beyond.

Older people with MS are the experts in living with the disease from day to day. With some notable exceptions,9 however, few older people have been asked about their experiences in living with MS and their trajectory of lifelong management of the disease. Studies examining social participation10 and coping11 in older people with MS find that a positive outlook, maintenance of social relationships, and an ability to adapt to the environment are critical to maintaining well-being. Over two-thirds of older people with MS, however, are limited in activities of daily living and in social and health-promotion activities.12 Although it has been suggested that self-management is important in living a long and healthy life with MS,13 we know little about the experience and timeline of MS self-management or about whether this concept is valued by people with the disease. For example, at what point are people with MS ready or prepared to self-manage? What tools or skills do they need to acquire?

Many people diagnosed with MS progress from denial to acceptance to self-advocacy.14,15 Uncertainty gives way to confidence over time, as images of disablement and death16 are replaced by confidence and understanding of one's own personal experience of MS.17 Furthermore, as people age with MS, their priorities shift, such that physical limitations have less influence on overall perceived quality of life than social and emotional functioning do.18,19 This discrepancy between self-reported quality of life and functional impairment, termed the “disability paradox,” has been reported by other people with long-term disability.20 Opinions of ageing with a disability such as MS may be different from those reported by people with more stable neurological symptoms, such as those experienced following stroke or spinal-cord injury.21 Furthermore, people ageing with a disability are concerned about the cumulative effects of other comorbid health conditions, such as cancer, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease.22 To date, we have insufficient information on the natural course of ageing with MS and how the emergence of comorbid conditions interact with MS self-management—critical information required for the development of MS self-management programmes.

It is important to establish who should help people with MS move toward self-management, including the role of peers and health professionals. Health providers' efforts are often viewed as futile, misdirected, and unilateral,17 but at the same time perceived as influential in enabling people with MS to self-manage.23 Health professionals need to know how to facilitate rather than obstruct self-management.

The goal of this study, therefore, was to describe the experience of ageing with MS from the point of view of the older person with MS. We used qualitative interviews and thematic content analysis to identify and describe facilitators and inhibitors of self-management, as well as to describe the continuum of ageing with MS.

METHODS

Participants

This qualitative study was approved by the Human Investigations Committee, Memorial University, and the Patient Research Committee, Eastern Health Authority. Potential participants were identified from MS clinic and rehabilitation outpatient records and initially contacted by telephone (using a script) by their health care provider to determine their interest in participating. Those who expressed interest were contacted by a member of the research team and were included if they were over age 55, had experienced symptoms of MS for at least 20 years, and lived within 90 minutes' travel distance from the study location. Participants who were in hospital at the time of the study were excluded. Of 35 potential participants, 18 participated in the study; 10 declined to participate, and 7 did not meet the study criteria. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Although cognitive status was not included as part of the study criteria, it became apparent during one interview that the participant had difficulty following the conversation; the interviewers decided to halt the interview, and the data were not included in the analysis.

Interview

The research team, after considering the aims of the study, designed the interview questions (see Box 1) based on review of the literature, experiences in community advocacy, and discussions with people with MS in the health care environment. A practice interview critically evaluated interviewer interruptions, judgements, prompts, and gaps. The participant, Maude, was approached for the first interview because of her previous experiences in health research; she agreed to permit more time and flexibility for this initial interview, which the research team later reviewed and modified for subsequent participants. Although the interview questions were consistent for all participants, prompts and follow-up questions were tailored to individual responses.

Each participant chose a convenient meeting location. Following introduction, consent, and collection of demographic data, participants engaged in a face-to-face semi-structured interview for 60–80 minutes, using open-ended questions. One investigator led the interview while the other recorded detailed field notes on verbal and nonverbal communication. Interviews were audiotaped for later transcription. Data saturation (the point at which no new information is obtained) was reached during the fourteenth and fifteenth interviews; three additional interviews were completed, however, to ensure the stability of the data.

Box 1. Interview Components.

Demographic Information

Number of years since the first onset of MS symptoms

Time since diagnosis

MS subtype

Family circumstances

Living situation

Education

Smoking

Alcohol intake

-

A

We would like to know more about your MS.

How long have you had MS?

How would you describe your MS and how it has progressed over the years?

-

B

We would like to know more about your typical day.

Describe what you would do most mornings, most afternoons, most evenings.

Is there anything else you can tell us about MS in your everyday life?

-

C

This is a study involving women and men who are 55 years of age and older.

What is it like to be a senior living with MS?

Do you have different ideas or approaches about living with MS now than you did when you were first diagnosed?

-

D

We would like to know more about your social relationships and supports.

Do you have family or friends that live nearby or far away?

What kinds of things do you do together?

How do friends and family relationships affect living with MS?

-

E

We would like to know more about how you stay healthy.

How do you feel about your health overall?

What types of things have you done that have helped you maintain your health?

Are there barriers or problems that you have faced that have hindered your ability to live successfully with MS? What have you done to address these?

How do you think the health care system and health providers affect living with MS?

What advice would you give about living healthy with MS?

-

F

We would like your advice on living with MS.

What advice would you give someone newly diagnosed with MS?

Is there anything else you would like to say about being an older person with MS?

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim; the primary interviewer (MP) then listened to the audiotapes and used the field notes to correct errors and add related nonverbal content. The second interviewer (MA) applied a consistent transcript format, removed identifiers, and then reviewed transcripts for completeness. Thematic content analysis was the basis of subsequent analysis, followed by an examination of theme and sub-theme relationships. Thematic content analysis was guided by a focus on validity (representativeness of participants' observations) and reliability (multiple interpretations of the data and consensus).24 To ensure data reliability, three investigators (MM, MP, AK) representing three “lenses” (community, health, and academic), read and re-read two content-rich transcripts, identified relevant content, and applied descriptive codes. The investigators then developed a provisional coding system of themes and respective sub-themes, which were redefined, consolidated, and regrouped by consensus through multiple iterations. Using the coding scheme, the primary investigator (MP) read and re-read the remaining 16 transcripts, identified content, applied codes, and sorted the codes into the themes and sub-themes using the qualitative analysis software NVIVO 8 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA). Two transcripts that contained a large amount of content that did not fit into the coding scheme were used to develop novel codes by the same three investigators. All transcripts were then re-reviewed to apply these novel codes. To ensure data validity and to guard against selectivity, strength of the evidence was determined by code frequencies (see Table 1), and the research team prioritized quotes that were representative of the interviews as a whole. After codes were grouped into sub-themes, investigators created interpretive summaries of each sub-theme, including verbatim quotes. To facilitate the framework analysis process, sub-theme summaries were transferred to cue cards in brief point form, and the investigators aligned and grouped the summary cue cards, by consensus, showing commonalities and relationships with directional arrows. The framework structure was photographed to develop a conceptual model of the natural history of MS self-management. When summary cards and their relationships were further scrutinized, emerging sub-themes not previously addressed through initial coding were identified. These sub-themes (e.g., stigma) were described by reassessing transcripts, codes, and interpretive summaries.

RESULTS

Participants

The 14 women and 4 men were of Euro-Canadian backgrounds, and all but 2 had at least some post-secondary education (13 bachelor's level; 3 post-bachelor's level). Twelve participants reported that they were married; three were widowed, and three were divorced. Participants reported their MS subtypes as relapsing-remitting (3), primary progressive (2), secondary progressive (10), benign (1), or unknown (2). Table 2 summarizes participants' demographic data.

Table 2.

Participant Profiles

| Pseudonym | Age, y | Duration of MS symptoms, y | Self-reported years since MS diagnosis | Mobility level | Living arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maude | 76 | 41 | 37 | Uses a cane | Alone in own home |

| Jeanette | 61 | 27 | 7 | Walks independently; limited by fatigue | Own home with housekeeping services |

| Elizabeth | 60 | 35 | 28 | Uses a scooter | Own home with help of spouse |

| Clark | 74 | 40 | 21 | Uses a walker | Own home with help of spouse |

| Donald | 61 | 36 | 15 | Uses a walker or a wheelchair | Own home with help of spouse |

| Dorothy | 63 | 31 | Does not recall | Uses either a power wheelchair or a scooter | Long-term care facility |

| Brenda | 60 | 20 | 18 | Uses a cane | Own home |

| Jackie | 67 | 23 | 17 | Uses a cane | Own home |

| Robert | 71 | 23 | Does not recall | Uses a power wheelchair | Long-term care facility |

| Sharon | 56 | 37 | 37 | Uses a power wheelchair | Own home with home-care services |

| Linda | 68 | 22 | 21 | Walks independently; limited by fatigue | Own home |

| Evelyn | 68 | 34 | 27 | Uses manual wheelchair and a scooter | Own home with home-care services |

| Annie | 60 | 30 | 26 | Uses a power wheelchair | Own home with home-care services |

| Mary | 63 | 24 | 21 | Walks independently | Own home |

| Gwen | 73 | 44 | 34 | Uses a manual wheelchair | Long-term care facility |

| Edith | 81 | 42 | 39 | Uses a manual wheelchair and a power wheelchair | Assisted living facility |

| Eric | 67 | 37 | 23 | Uses a cane | Own home with help of spouse |

| Rose | 72 | 20 | 11 | Walks with help | Own home with help of spouse |

MS=multiple sclerosis.

Interview Content

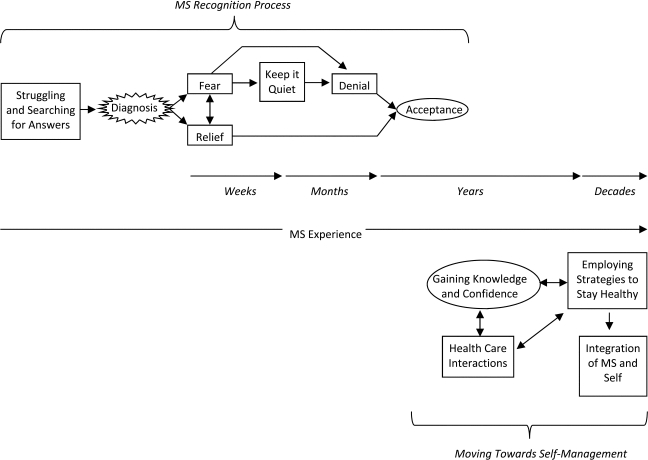

Participants described a process, spanning years and often decades, from MS diagnosis to self-confidence in managing MS. Three overlapping chronological themes or phases, representing the natural continuum of MS self-management, emerged from the thematic content and framework analysis (see Figure 1): the MS recognition process, the MS experience, and moving toward self-management. Table 1 summarizes these phases (themes) and the code frequencies by sub-theme.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the path to MS self-management, described by older people with MS, from symptom onset to integration of MS into a sense of self.

Table 1.

Theme and Sub-theme Code Frequencies

| Themes and sub-themes | No. of participants | No. of comments |

|---|---|---|

| MS Recognition process | ||

| Fear | 12 | 23 |

| Unknown becomes known | 9 | 21 |

| Searching for answers | 10 | 14 |

| Struggle | 12 | 14 |

| Denial and acceptance | 7 | 11 |

| Relief | 3 | 7 |

| Keeping it quiet | 4 | 7 |

| Ignorance is bliss | 3 | 4 |

| The MS experience | ||

| Symptoms | 18 | 74 |

| Changes in physical and social activity | 13 | 38 |

| Comorbid health conditions | 13 | 29 |

| Impact of stress | 16 | 28 |

| Opinions of overall health | 16 | 22 |

| Worst ever experiences | 10 | 12 |

| Moving toward self-management | ||

| Adaptation / gaining knowledge and confidence | 17 | 69 |

| Access to health care | 17 | 63 |

| Enabling health care interactions | 15 | 42 |

| Exercise, diet, and complementary therapies | 17 | 40 |

| Medications | 16 | 33 |

| Unhelpful health care interactions | 8 | 13 |

MS=multiple sclerosis.

The MS Recognition Process

The Struggle and Search for Answers

Participants recounted the struggle for a final MS diagnosis as a very stressful and worrying period in their lives. Escalating uncertainty and fear and insufficient communication with health care providers were hallmarks of this period, which for some lasted more than 10 years. Evelyn felt that some family members catastrophized her symptoms, making her believe she was “going to die.” Jackie's doctor told her she had a viral infection; she felt she “didn't get much satisfaction from him.” Since most participants were diagnosed before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) became available, they described undergoing multiple diagnostic tests over many years, repeated frequently in different health centres. Evelyn recalled, “It was actually seven years until I went to Montreal and was diagnosed.” At the time of the interview, up to 30 years later, some participants were still upset that they were first diagnosed with conditions other than MS or were told that there was “nothing wrong.”

Fear

Fear was a content-rich sub-theme (23 comments among 12 participants; see Table 1) that participants described feeling during the MS recognition phase and for the first few years after diagnosis. They recalled feeling “devastated,” “as if my life was over,” “frightened to death,” and described anticipating their future as “horrendous” and fraught with “horrible things.” Describing her fears during the 7 years from the onset of her symptoms to diagnosis, Evelyn said, “I knew it was something dire.” While some participants described a relatively short period of fear after diagnosis (days to weeks), others said they cried for long periods and became depressed. They worried about their children, their mortgages, their jobs, and the unknown. For example, Annie said, “I had four children at home … babies. A year and a half my youngest was. My first thought was, ‘What am I going to do?’” Most participants were concerned about how their MS would progress. Recalling her feelings around the time of her diagnosis, Gwen reflected, “It was a fear of the unknown. What is going to happen? What can happen?” Anxiety around anticipating frequent doctor visits and tests and about relying on wheelchairs and catheters were common. Fear was intensified if the participant knew someone with MS or had known someone with MS who had died. One participant felt that, as a nurse, she “knew too much” of what could potentially happen in severe cases. Another recounted feelings of fear after reading about MS-related “horror stories.”

Relief

Although fear was the most common feeling during the time of MS diagnosis, a few participants (7 comments among 3 participants; see Table 1) also reported a sense of relief from feeling “worried all the time” and “in limbo” once their diagnosis was confirmed; they felt they could then move on to dealing with it. Mary felt that “at least there was a reason … things started to make sense to me.” She reported feeling relieved that the diagnosis was not something worse, such as a tumour: “I was almost grateful.” Jackie felt relieved when she was told her MS was more benign.

Keeping It Quiet

Four participants reported that they did not want anyone, other than their spouses and immediate family, to know about their MS diagnosis. Revealing the diagnosis of MS to others was a challenge. Upon diagnosis, Eric informed his work supervisor, but asked that his diagnosis be kept private from his co-workers because “it was like there was a shame” and he didn't like “being made a spectacle of.” It seemed that for some, informing others was a sign of acceptance of MS that they were not prepared for. Linda said, “I couldn't even bring myself to tell anybody because I was trying to deal with it myself.”

Denial and Acceptance

Participants recalled refusing to think about MS, disbelieving their diagnosis, not acknowledging it, and “objecting to” and “fighting it.” Several remembered denying the MS diagnosis despite having obvious mobility problems, such as falls. Brenda felt that “ignorance is bliss,” and that “not knowing might have been a very positive thing.” Eventual acceptance was “not a conscious effort” but a “gradual process” that unfolded in different ways; for some it was a realization that the symptoms were getting worse and could no longer be ignored, while for others it was realizing that they were needed by others, so they “got on with it.” However, participants did not equate acceptance with giving in or giving up. Evelyn “objected every step of the way,” but at the same time had a sense that “no matter how much you want to walk and be normal, you cannot do it.”

The MS Experience

Symptoms

The diverse symptoms recounted by participants included fatigue, incontinence, weakness in the extremities, falls, ataxic gait, numbness, pain, double vision, depression, spasticity, unexplained sensations, heat sensitivity, memory problems, and balance issues. Depression, pain, and bladder and bowel incontinence were commonly described as participants' “worst ever” symptoms. Jackie, in describing an 8-month bout of trigeminal neuralgia, said, “It really makes you think about suicide, it really does.” Many described frequent steroid treatments that usually improved their symptoms. Three participants reported that hospitalization for an unrelated health condition resulted in an apparent worsening of mobility-related MS symptoms. When asked how they managed their exacerbations, participants talked about resting when they felt the initial harbingers of an exacerbation (often fatigue), managing their schedules and daily activities, and making use of adaptive devices. Some described “a very gradual downhill slope” and adapting to changes so that they could still participate in valued activities. Robert said, “I was right-handed but now I don't have much control in it. But my left hand is pretty good so I have learned to write with it. So I sort of just made these adjustments and sort of accepted them.”

Changes in Physical and Social Activity

Changes in physical and social activity as a result of MS symptoms were strongly linked together, and the content of this sub-theme was rich and multifaceted (38 comments among 13 participants; see Table 1). Some participants felt this loss acutely, and grieved over it, while others described moving on to find other activities and ways of staying engaged. Ability to solve problems and capacity for self-evaluation seemed to be important for making decisions to maintain physical and social participation. Jackie described several instances when, rather than discontinue a challenging activity, she adopted a new strategy; on walking uphill, she said, “I can judge it. I just sit and wait until I get my energy back.” In contrast, Clark spoke of enjoyable activities that he abruptly discontinued and replaced with watching television: “I liked puttering in the garage but can't do any of that because of my balance.” The absence of a supportive spouse, an inaccessible environment, and living in a long-term care facility all created barriers to social and physical engagement.

Participants who were less socially engaged tended to describe more feelings of inevitability and powerlessness. Evelyn felt that once she enlisted home-care services, friends and family visited less often, because they were no longer “needed.” Gwen grieved the move to a long-term care home: “I don't get up too early,” she said, “because there is not a lot to do.” Because many churches and community centres are not accessible, participants' social networking opportunities became limited. Dorothy felt that because she was no longer able to volunteer, she had fewer reasons to be in contact with others: “Fewer and fewer people are bothering to send e-mails now because I don't go out anymore.” Inaccessible public transportation services exacerbated the experience of social isolation. Retirement from work resulted in lost opportunities for social engagement, as Mary says: “One of the things that I found difficult was losing friendship because you are no longer in the workforce. It becomes a pretty lonely thing.”

Most participants described a loss of independence in their activities of daily living over time; for example, manual dexterity was often a limiting factor with hobbies such as knitting and using the computer. Annie said, “It is difficult to be entirely dependent on other people for all of your activities of daily living. It is difficult to accept that you are a dependent person.” Eric acutely felt the loss of his roles around the house, such as clearing snow: “It kills me to see my wife out there at it. I figure that should be one of my jobs.”

Although participants described barriers to physical exercise, some reported light to moderate physical activity as part of their current daily activities. Participants explained that although MS symptoms had caused them to give up some of their preferred activities, such as swimming or skiing, they chose other activities that were more manageable, such as using small dumbbell weights at home.

Comorbid Health Conditions

Many participants expressed more concern about other critical health problems, such as cancer, than about their MS. Although many felt that MS was “not deadly,” they recognized that some other health problems were related to MS, including depression, pressure ulcers, and urinary-tract infections. Elizabeth said that she has “age-related issues,” including osteoporosis that is “aggravated by the fact that I can't exercise.”

Impact of Stress on MS

Opinions on the impact of stress on MS symptoms were equivocal. Some participants felt that stress, although bothersome, did not aggravate their MS, while others felt that it played a role both in the initial onset of their MS symptoms and in later symptom exacerbations. Describing a confluence of major stressors in her life (death of a parent, moving house) that coincided with an exacerbation of her MS symptoms, Sharon said, “That was the pivotal thing that set it off.”

Overall Health

Many participants equated lower overall health with the presence of other serious health conditions, including depression, rather than with MS-related health and disability. Although she described very mild MS-related problems, Jeanette felt her overall health was “poor,” mainly because she felt depressed and was not satisfied with her relationship with her spouse. However, opinions and perceptions of overall health and how it was affected by MS ranged considerably. For example, Maude described “my MS” as being more of a nuisance to her than “something serious like cancer” would be. Some participants considered their health good compared to that of other people their age or of other people with MS. Robert joked that he “read the obituaries” to gain perspective. For many, overall health was not related to extent of disability. For example, despite requiring substantial help with activities of daily living, Robert said, “I have prostate cancer. I have MS, but otherwise my health is generally good. I eat well.” However, two participants strongly articulated that they felt MS negatively affected their overall health. Mary said, “My mother is 20 years older than I am and I can't keep up with her. I do feel that I've been cheated. I have been made an old woman before my time.”

Moving Toward Self-Management

Adapting and Gaining Knowledge and Confidence

Participants described learning about what to expect from MS relapses and progression over the first few years following diagnosis. They supplemented this experiential trial-and-error learning by joining support groups, reading books, and consulting with health care professionals, as well as through word-of-mouth advice from friends and family. When asked how her MS had changed over the years, Maude said, “Most of the change has been in me.” Many participants felt that they were more knowledgeable than health care providers about their MS. Rather than feeling that MS was a disease that affected them, they described it as part of their sense of self. Family and other health concerns seemed to take priority over MS-related issues. Jackie said, “I mean, it's something that I've lived with for almost 25 years. I don't notice it as much anymore.”

Participants emphasized planning for future challenges (e.g., financial and social supports). Linda felt that someone newly diagnosed with MS “should really try to find out everything they can.” She said that discovering the variable nature of MS helped her to “feel a lot better” and to realize that “it's not the end of the world, because every case is different.”

Participants felt that they constantly adjusted to a “new normal.” Gwen, in describing how she used walking aids to keep mobile, said, “What's normal anyway?” Participants made changes such as purchasing fewer groceries at one time and eventually having their groceries delivered. Some participants recalled using canes to walk, then a walker, a wheelchair, and eventually power mobility. Some, who experienced memory problems, adopted various strategies that they found helpful, such as writing down a daily schedule.

Participants also reflected on adaptations made early on that they now believed had been unsuccessful. For example, Evelyn began to rely upon her husband to complete household chores; following their divorce, she found herself initially unable to perform many tasks, and had to re-adapt. Sharon decided against installing hand controls in her car, but now believes that this was a mistake because she eventually had to stop driving, which became a barrier to social engagement for her.

Emotions around the use of assistive devices were polarized. Participants who discussed their adaptive equipment expressed positive attitudes toward adaptive devices such as wheelchairs and scooters. In some cases, equipment allowed them to continue employment that otherwise would have ceased. Elizabeth referred to her power chair as “a godsend.” However, participants also identified a negative attitude toward devices such as wheelchairs on the part of both the general public and others with MS. Some recalled fearing that making use of adaptive equipment would result in more reliance on the device and more disability. Others felt that wheelchairs acted as a clear marker of disability and sometimes resulted in prejudice. In some cases this meant being offered help by strangers that was not always desired. Edith said, “When anybody sees you in a wheelchair, what they see is the wheelchair, and they are inclined to say, ‘How is she?’ instead of saying, ‘How are you?’”

Accessing Health Care

Although many participants felt both confident and competent in managing their MS at the time of interview, they also described consulting a wide array of health care professionals over the years. Dorothy discussed the importance of access to health professional services in allowing her to stay independent at home. She received advice on bathroom modifications from an occupational therapist and enlisted a physiotherapist to help with her home exercise programme. Some participants discussed waiting longer than they would have liked to see a specialist and relying on their family physician in the interim. Eric reported waiting a year to see a physiotherapist because his referral was “lost in the health care system.” Participants valued health insurance and special assistance programmes for funding of equipment and medical supplies. Home-care workers and individuals who provided services such as housekeeping were important to living independently at home. The sense of security achieved by having access to a wide array of care providers was very important to the group.

Health Care Interactions

Participants valued health care interactions that involved two-way communication rather than health care providers simply “telling” or informing. They relied heavily on, and held in high regard, health care providers they considered knowledgeable in MS care and who maintained a collaborative relationship with them. Edith said of her family doctor, “We understood each other. He listened to what I had to say and paid attention to what I said. He told me about everything that was going on, but he left it to me to decide if I wanted to take part or not.” Robert felt pleased because he could “relate to” his new neurologist, whereas previous encounters with other doctors had been “almost insulting.” Unhelpful care reported by participants was often due to ineffective listening and communication by health professionals. Some participants felt that their health care providers did not have enough time for them, which they believed was likely the result of understaffing. These factors often made them reluctant to seek out help when it was needed.

Medications, Therapies, and Strategies to Stay Healthy

Participants' desire to stay healthy and reduce the progression of disability was immense. Although only three participants recalled trying disease-modifying drugs, most were either currently using medications for MS-related symptoms (e.g., depression, spasticity) or had required medication in the past. Drug effectiveness seemed to be assessed by trial and error. Sharon was pleased about recent advances in drug therapies: “One thing that irritates me is somebody just diagnosed with MS refusing to go and get treatment [by taking currently available medications]. I would have loved to have a chance to have those treatments back then.”

Use of nutrition supplements (e.g., vitamins, fatty acids) and complementary therapies (e.g., bee-sting therapy, marijuana, stem-cell therapy) was common. Some participants demonstrated great perseverance in pursuing therapies. Annie admitted that she felt no benefit from the 450 bee stings she had received, but said, “Look, if they told me I could go to Mars to get rid of MS, I would have done so. So I tried bee-sting therapy.” Many participants diligently followed low-fat diets they had either read about or heard about from friends with MS. Most reported a moderate intake of alcohol, and only one participant described himself as a smoker. Participants also related a lifelong commitment to physical exercise, although this was not without challenges. They reported frequently modifying their exercise habits during exacerbations or when their fatigue or mobility levels changed.

DISCUSSION

The Natural History of Self-Management

Although self-management has been suggested to be important in maintaining quality of life when living with a chronic health problem,12 there is little research on the optimal process, structure, timing, and usefulness of self-management in MS. We undertook this study involving older people with MS to learn more about the natural history of MS self-management (see Figure 1). Preceded by uncertainty and fear, the diagnosis of MS is a monumental moment in one's life.15,23,25 Participants in this study had vivid recollections of fear, denial, confusion, and sometimes a sense of relief in the weeks and months following diagnosis. Like Somerset and colleagues,17 we found that specific words and phrases spoken at the time of diagnosis influence people with MS for many years, which suggests that health professionals should be especially sensitive in the way they communicate during this phase. As others have found,16 many participants initially anticipated a catastrophic outcome, but their expectations became more balanced over time, tempered by their own experience and knowledge. Several participants wished to keep their diagnosis private, possibly to protect others' emotions or to maintain a sense of normalcy in social and work environments.25 Although denial was a common theme among our participants, it did not seem to be a complete impediment to self-management. For example, both Robert and Evelyn described “objecting every step of the way,” yet still seemed to make adaptations, seek out information, and solve problems related to MS. This suggests that acceptance is not necessarily a prerequisite to learning self-management strategies.

The devastation of symptom onset is lessened by knowledge of the disease.14 In our study, participants described a process by which fear and uncertainty were replaced with growing knowledge and confidence in managing “their MS.” Although one would expect that feelings of fear and uncertainty would continue for years following diagnosis, participants in this study (many diagnosed without MRI) described dissipation of fear, and even relief, following diagnosis, probably because they had waited for some time—in some cases more than 10 years—for confirmation of MS. Through trial and error, learning from friends with MS, books, and advice from health professionals, participants became expert in managing their disease. Sometimes this process took decades, depending on the individual. Some seemed to take on an active self-management role early, while others described a more “gradual process.” Although the passage of time is clearly an important component in the process of accepting and integrating MS into a sense of self,15,22 seeking out health-promoting activities and treatments and learning from “mistakes” also seem to have been important methods for our participants to take control of managing their disease.26 Since early lifestyle choices, such as smoking,27 and comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease28 are associated with more rapid progression of MS-related disability, earlier implementation of wellness strategies could influence the long-term health and quality of life in people with MS. Self-management programmes, for example, may have the potential to shorten the decades-long process of obtaining competence in self-management to months or years (see Figure 1). Our findings suggest, however, that participants did not experience clear distinctions between the phases of denial, acceptance, and integration, which makes it difficult to determine either when a self-management phase begins naturally or when self-management programmes should be implemented.

A Self-Management Toolkit

A major challenge in the field of MS self-management is the development of an evidence-based “toolkit”—understanding what issues should be addressed and how content should be delivered.13 Our findings suggest that dealing with loss and navigating barriers, especially in the areas of employment, independence, and social participation, are critical components of MS self-management. It was also clear that a “one size fits all” approach did not match participants' experiences of living with MS; the strategies they employed to solve problems were highly individual. Many of the “worst ever” MS-related symptoms described by our participants (pain, bowel and bladder incontinence, and depression) were those that impeded work and social participation. Methods to minimize the impact of these symptoms should clearly be included in self-management curricula.

In this study of a natural chronology of MS self-management, many of the coping and problem-solving strategies described by participants were individual, and some people seemed to be innately better than others at coping with challenges. Individuals who demonstrated strong problem-solving skills and a strong capacity for self-evaluation tended to describe their approach as lifelong rather than learned; those who described weaker problem-solving strategies were more likely to report a sense of inevitability, and they experienced more insurmountable obstacles to social and physical participation. Although more advanced problem-solving capabilities could be partially explained by the fairly high levels of post-secondary education in our study group, we did not see a trend toward an association between higher education and better coping. Our findings suggest that when assisting in self-management, health providers and facilitators should consider clients' problem-solving capacity. Although several study participants demonstrated strong problem-solving skills, those who have yet to develop these strategies will require guidance from health professionals and peers to validate coping strategies and teach step-by-step problem-solving techniques.14

Participants made use of a wide assortment of devices to assist mobility. The benefits of assistive devices are strongly supported by past evidence29; study participants reported some reluctance to use adaptive equipment, however, which seemed to be rooted in concerns about “giving in” and a fear of adopting a “disabled” persona. Feelings around the use of assistive devices seemed to be polarized: on the one hand, people were concerned about stigma and dependence on devices, while on the other hand they emphasized the benefits that assistive devices provide. This suggests that self-management programmes should address the use of assistive devices, including the emotional and psychological impressions associated with them.

Our data suggest that the ageing process and other comorbid conditions, combined with the symptoms of MS, influenced how the older people in our study perceived their overall health. Participants seemed to equate better health with the absence of other comorbid conditions, rather than assessing their health based on MS-related disability. Several participants said that health care providers often inaccurately attributed concerns about other health problems to MS, or dismissed them altogether. Our findings support the notion that attention to comorbid conditions and continued health monitoring, such as cancer and osteoporosis screening, should be components of MS self-management programmes.

Participants in our study also seemed to value being needed by others and having a strong social network over issues around physical abilities. The severity of losses in physical ability seemed to be calibrated to their social impacts. As others have reported,18 health-related quality of life is interpreted differently by older people with MS than by those who are younger; older people assign more importance to psychosocial and emotional health. Although older people with MS have untapped potential as advisors for health professionals and for people newly diagnosed with MS, these different views are important to consider when older people with MS act as mentors as part of self-management programmes. Misunderstanding and conflict could be avoided if these perspectives are discussed openly.

The Role of Health Professionals

The study group placed a great deal of faith and trust in health care providers in helping them to learn how to best manage their MS, but they became more competent and confident in self-management over time. The initial struggle to find a reason for their symptoms was burdensome for participants and accounted for the greatest number of unhelpful health-related interactions. Miscommunication and misunderstanding by health care providers has been found to leave patients feeling powerless;17 patients who perceive health professionals as unsympathetic have reported feeling disappointed, bitter, and angry.25 Although other research suggests a preponderance of unhelpful health care experiences,14,15 participants in our study seemed to take a more balanced view, perhaps because they recounted a great number of lifelong health care interactions and had more time to reflect upon their experiences. Nonetheless, our findings support the conclusion that people with MS value health professionals who listen and discuss rather than simply informing or advising.14 Participants respected health care providers whom they considered experts in MS care and who could give them current and specific information.30,31 Health care professionals who acknowledge the limitations of MS treatment yet assume a supportive and facilitative role have been found to be helpful in the move toward self-management.23 Our participants made it clear that adequate access to a variety of health care professionals, including family doctors, neurologists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and other specialists who provide a supportive and understanding environment, was important in addressing barriers to lifelong management of MS.

Our study has several limitations. Because this was a qualitative study, our findings are influenced by the backgrounds of the participants. Most participants had at least some post-secondary education and came from what could be considered middle-class backgrounds, which may have influenced their outlook, their coping ability, their financial situation, and how they accessed services. It is important to stress, however, that not all participants considered themselves MS experts. Many described lifelong struggles with managing MS and its physical, emotional, and social consequences. Interviews conducted with participants from different backgrounds might yield different results, but this does not discount or minimize the experiences recounted by this group. Although the study took place in the context of a publicly funded health care system, it was clear that not all services were publicly funded or easy to access, and MS self-management is an aspect of health care that crosses most methods of health delivery.

Since this study involved older people with MS diagnosed before the use of MRI, the period between onset of symptoms and final diagnosis was often more than 10 years. Participants described experiencing fear and uncertainty during these intervening years, which were lessened following confirmation of MS. Since MRI permits more rapid MS diagnosis, people newly diagnosed with MS may have a more prolonged experience of fear following diagnosis than this older participant group.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study sought to gain an understanding of the natural history of MS self-management from the point of view of older persons with MS. Participants described the knowledge, abilities, facilitators, and inhibitors surrounding their experiences of ageing with MS. Gaining knowledge of the diversity of MS experiences helped to lessen fear; self-determination, social support, strong problem-solving abilities, and maintaining collaborative relationships with health professionals aided adaptation and coping. In this group of older people with MS, maintaining social participation seemed to take priority over maintaining physical ability. Based on these findings, we developed a conceptual model of the decades-long natural history of MS self-management (see Figure 1). Our findings suggest that MS self-management programmes should endeavour to shorten the early experiential learning phase of living with MS to promote earlier implementation of health-promoting activities and the integration of MS into the sense of self.

KEY MESSAGES

What Is Already Known on This Topic

Self-management has been suggested to be important in living a long and healthy life with a chronic disease such as MS. We know little about the experience and timeline of MS self-management, however, or about whether the concept is valued by people with the disease.

What This Study Adds

Gaining knowledge of the diversity of MS experiences helped participants to alleviate feelings of fear associated with their MS diagnosis. Self-determination, strong problem-solving abilities, and maintaining collaborative relationships with health professionals aided adaptation and coping. In this group of older people with MS, maintaining social participation seemed to take priority over maintaining physical ability. This study adds to a growing body of literature that can help rehabilitation providers and people with MS make decisions about the optimal timing, structure, and content of MS self-management programmes.

Physiotherapy Canada 2012; 64(1);6–17; doi:10.3138/ptc.2010-42

References

- 1.Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. About multiple sclerosis [Internet] Toronto: The Society; n.d.. [cited 2010 Oct 26]. Available from: http://mssociety.ca/en/information/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E, et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133(7):1900–13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq076. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq076. Medline:20423930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(7):1914–29. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq118. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq118. Medline:20534650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Adeleine P. Early clinical predictors and progression of irreversible disability in multiple sclerosis: an amnesic process. Brain. 2003;126(4):770–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg081. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg081. Medline:12615637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson M, Andersen O, Runmarker B. Long-term follow up of patients with clinically isolated syndromes, relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):260–74. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms914oa. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms914oa. Medline:12814173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrie RA, Horwitz RI. Emerging effects of comorbidities on multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):820–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70135-6. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70135-6. Medline:20650403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuifbergen AK, Blozis SA, Harrison TC, et al. Exercise, functional limitations, and quality of life: A longitudinal study of persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(7):935–43. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.003. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.003. Medline:16813781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veugelers PJ, Fisk JD, Brown MG, et al. Disease progression among multiple sclerosis patients before and during a disease-modifying drug program: a longitudinal population-based evaluation. Mult Scler. 2009;15(11):1286–94. doi: 10.1177/1352458509350307. doi: 10.1177/1352458509350307. Medline:19965558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finlayson M, Van Denend T, DalMonte J. Older adults' perspectives on the positive and negative aspects of living with multiple sclerosis. Br J Occup Ther. 2005;68(3):117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fong T, Finlayson M, Peacock N. The social experience of aging with a chronic illness: perspectives of older adults with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(11):695–705. doi: 10.1080/09638280500277495. doi: 10.1080/09638280500277495. Medline:16809212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DalMonte J, Finlayson M, Helfrich C. In their own words: coping processes among women aging with multiple sclerosis. Occup Ther Health Care. 2004;17(3/4):115–37. doi: 10.1080/J003v17n03_08. doi: 10.1080/J003v17n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Einarsson U, Gottberg K, Fredrikson S, et al. Activities of daily living and social activities in people with multiple sclerosis in Stockholm County. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(6):543–51. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr953oa. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr953oa. Medline:16892936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser R, Johnson E, Ehde D, et al. Patient self-management in multiple sclerosis: a white paper [Internet] The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; 2009. [cited 2010 Oct 26]. Available from: http://mscare.org/cmsc/images/pdf/CMSC_whitepaper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courts NF, Buchanan EM, Werstlein PO. Focus groups: the lived experience of participants with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36(1):42–7. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200402000-00007. Medline:14998106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koopman W, Schweitzer A. The journey to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999;31(1):17–26. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199902000-00003. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199902000-00003. Medline:10207829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isaksson AK, Ahlström G. From symptom to diagnosis: illness experiences of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38(4):229–37. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200608000-00005. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200608000-00005. Medline:16924998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somerset M, Sharp D, Campbell R. Multiple sclerosis and quality of life: a qualitative investigation. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(3):151–9. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082454. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082454. Medline:12171745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts G, Stuifbergen AK. Health appraisal models in multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(2):243–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00080-x. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00080-X. Medline:9720643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowling A, Iliffe S. Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):607–14. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl100. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl100. Medline:16951427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(8):977–88. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00411-0. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00411-0. Medline:10390038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whalley Hammell K. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(2):124–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101992. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101992. Medline:17091119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yorkston KM, McMullan KA, Molton I, et al. Pathways of change experienced by people aging with disability: a focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(20):1697–704. doi: 10.3109/09638281003678317. doi: 10.3109/09638281003678317. Medline:20225933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorne S, Con A, McGuinness L, et al. Health care communication issues in multiple sclerosis: an interpretive description. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/1049732303259618. doi: 10.1177/1049732303259618. Medline:14725173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green JT, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards RG, Barlow JH, Turner AP. Experiences of diagnosis and treatment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):460–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00902.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00902.x. Medline:18373567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salamonsen A, Launsø L, Kruse TE, et al. Understanding unexpected courses of multiple sclerosis among patients using complementary and alternative medicine: A travel from recipient to explorer. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2010;5(2):1–19. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5032. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5032. Medline:20616888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Pauli F, Reindl M, Ehling R, et al. Smoking is a risk factor for early conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14(8):1026–30. doi: 10.1177/1352458508093679. doi: 10.1177/1352458508093679. Medline:18632775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1041–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125. Medline:20350978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souza A, Kelleher A, Cooper R, et al. Multiple sclerosis and mobility-related assistive technology: systematic review of literature. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(3):213–23. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.07.0096. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2009.07.0096. Medline:20665347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker LM. Sense making in multiple sclerosis: the information needs of people during an acute exacerbation. Qual Health Res. 1998;8(1):106–20. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800108. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800108. Medline:10558325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller C, Jezewski MA. A phenomenologic assessment of relapsing MS patients' experiences during treatment with interferon beta-1a. J Neurosci Nurs. 2001;33(5):240–4. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200110000-00004. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200110000-00004. Medline:11668882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]