Homeostatic TH17 differentiation in the intestine is regulated by IL-1β secretion from intestinal macrophages stimulated by commensal microbiota.

Abstract

TH17 cells are a lineage of CD4+ T cells that are critical for host defense and autoimmunity by expressing the cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22. A feature of TH17 cells at steady state is their ubiquitous presence in the lamina propria of the small intestine. The induction of these steady-state intestinal TH17 (sTH17) cells is dependent on the presence of the microbiota. However, the signaling pathway linking the microbiota to the development of intestinal sTH17 cells remains unclear. In this study, we show that IL-1β, but not IL-6, is induced by the presence of the microbiota in intestinal macrophages and is required for the induction of sTH17 cells. In the absence of IL-1β–IL-1R or MyD88 signaling, there is a selective reduction in the frequency of intestinal sTH17 cells and impaired production of IL-17 and IL-22. Myeloid differentiation factor 88–deficient (MyD88−/−) and germ-free (GF) mice, but not IL-1R−/− mice, exhibit impairment in IL-1β induction. Microbiota-induced IL-1β acts directly on IL-1R–expressing T cells to drive the generation of sTH17 cells. Furthermore, administration of IL-1β into GF mice induces the development of retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor γt–expressing sTH17 cells in the small intestine, but not in the spleen. Thus, commensal-induced IL-1β production is a critical step for sTH17 differentiation in the intestine, which may have therapeutic implications for TH17-mediated pathologies.

TH17 cells are a selective lineage of CD4+ T helper cells that are critical for host defense and autoimmunity by expressing the proinflammatory cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 (McGeachy and Cua, 2008; Ouyang et al., 2008; Korn et al., 2009). The induction of TH17 cells during inflammatory conditions such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) requires cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, and TGF-β1 (Korn et al., 2009). In addition to their presence during inflammatory responses, a population of T cells that expresses retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor γt (Rorγt), which is a TH17-specific transcription factor, is also found at steady state (sTH17) in the small intestine lamina propria (LP; Ivanov et al., 2006; Ivanov et al., 2008), where they accumulate only in the presence of luminal commensal microbiota (Atarashi et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2008; Ivanov et al., 2008). Recently, one member of this bacterial community, the Clostridia-related segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), was shown to be capable of inducing the generation of TH17 cells, as well as other subsets of TH cells (Ivanov et al., 2009). It has been suggested that the induction of ATP (Atarashi et al., 2008) and serum amyloid proteins (Ivanov et al., 2009) by commensal bacteria are required for promoting the generation of intestinal TH17 cells. However, the host signaling pathway linking the microbiota to the induction of intestinal sTH17 cells at steady state remains to be fully elucidated.

IL-1R signaling is important for murine TH17 development (van Beelen et al., 2007; Chung et al., 2009; Gulen et al., 2010) and accordingly, mice lacking IL-1R expression exhibit impaired capacity to generate TH17 cells in the setting of EAE (Sutton et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2009). Furthermore, the IL-1β–IL-1R signaling pathway has been shown to promote IL-17 production by the unconventional γδ T cells in the presence of commensal bacteria (Sutton et al., 2009; Duan et al., 2010). Based on analysis of intracellular staining of LP cells for TH17-associated cytokines after stimulation with phorbol ester and ionomycin, it was suggested that myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) signaling pathways that include Toll-like receptor (TLR) and the IL-1β–IL-1R signaling pathways were not important in inducing the development of normal TH17 cell responses in the small intestine (Atarashi et al., 2008; Ivanov et al., 2009). Because recent findings revealed that phorbol ester and ionomycin stimulation may exaggerate intracellular IL-17 expression in TH17 cells (Hirota et al., 2011), it remains unclear whether MyD88 signaling pathways play a role in the induction of intestinal sTH17 cells in animals colonized with gut-residing bacteria. In the present study, we examined the role of IL-1R and MyD88 signaling in influencing the induction of sTH17 cells in the intestinal microenvironment. Our results revealed that the microbiota induces the production of IL-1β, but not IL-6, in LP phagocytes and that stimulation of IL-1β–IL-1R signaling is necessary and sufficient in driving the generation of intestinal sTH17 cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

IL-1β–IL-1R signaling promotes the development of intestinal sTH17 cells

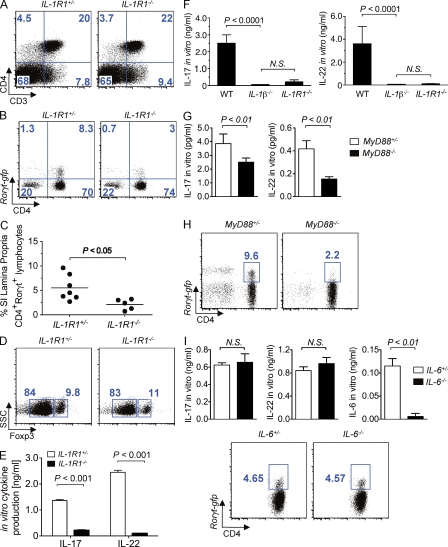

To assess the role of IL-1R signaling in the development of sTH17 cells under steady-state conditions in vivo, we crossed Rorc(γt)-gfp reporter mice, which express GFP under the control of the promoter of Rorγt (Eberl et al., 2004; Ivanov et al., 2006), with Ilr1−/− mice to generate Rorc(γt)-gfp reporter mice in the presence and absence of IL-1R. Although the frequency of total CD4+ T cells was not significantly different (Fig. 1 A), the numbers of Rorc(γt)-gfp+ CD4+ T cells were greatly reduced in the LP of Ilr1−/− mice compared with those in wild-type littermates (Fig. 1, B and C). The impaired generation of LP sTH17 cells was not the result of enhanced development of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells in the absence IL-1R1 signaling, given that no differences were observed in the frequency of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells between Ilr1−/− and the littermate control mice (Fig. 1 D). Consistent with the reduced frequency of sTH17 cells in vivo, the production of TH17-associated effector cytokines (IL-17 and IL-22) by FACS-sorted intestinal CD3+CD4+ IL-1R−/− cells, was also blunted after in vitro stimulation (Fig. 1 E). The impaired generation of sTH17 cells observed in the Ilr1−/− mice was not caused by the lack of intestinal colonization with SFB, as Ilr1−/− and controls animals maintained in our specific pathogen–free (SPF) facility had a comparable number of fecal SFB as determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of 16s rRNA gene sequences (unpublished data). In addition, the expression of IL-6 and IL-23p19 in the small intestine was unaffected by the absence of IL-1R1 signaling, as qPCR analysis revealed that the transcript levels of these genes were similar between Ilr1−/− and wild-type littermate animals (unpublished data). The proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β is a known ligand that interacts with IL-1R1 to mediate its biological effects (Sims and Smith, 2010). Accordingly, the in vitro production of IL-17 and IL-22 by LP cells isolated from Il1β−/− and Ilr1−/− mice was similarly reduced (Fig. 1 F). In contrast, the production of the Th1-associated cytokine IFN-γ by total LP cells was not impaired after in vitro stimulation (unpublished data).

Figure 1.

IL-1β–IL-1R and MyD88 signaling promotes the development of intestinal sTH17 cells. (A–C) Representative FACS dot plots of small intestine LP lymphoid cells from the indicated mice are shown in A and B, and the percentage of Rorγt-gfp+ CD3+CD4+ of individual mice are shown in C. Cells were pregated on total lymphocyte population in A and on CD3+ cells in B. (D) Representative FACS dot plot analysis of Foxp3 expression gated on total LP CD3+CD4+ cells of indicated mice. (E) Production of intestinal IL-17 and IL-22 by sorted CD3+CD4+ cells from the indicated mice was assessed ex vivo after stimulation with anti-CD3. (F) Production of IL-17 and IL-22 by (106 cells/ml) total LP cells from indicated mice was assessed ex vivo after stimulation with anti-CD3. (G) Production of intestinal IL-17 and IL-22 by sorted CD3+CD4+ cells from the indicated mice was assessed ex vivo after stimulation with anti-CD3. (H) Representative FACS dot plots gated on small intestine LP CD3+ cells in the indicated mice. (I) Production of intestinal IL-17 and IL-22 by sorted CD3+CD4+ cells from the indicated mice was assessed ex vivo after stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody (top). Representative FACS dot plots gated on small intestine LP CD4+ cells in the indicated mice (bottom). In vitro cytokine results shown in panels E–G and I are presented as means + SD from three to four individual mice per group. FACS results shown in panels A, B, D, H, and I are representative of two to five independent experiments with similar results.

The development of intestinal sTH17 responses requires MyD88, but not IL-6

Given that the adaptor molecule MyD88 plays a critical role in both TLR- and IL-1R–signaling pathways (Medzhitov et al., 1998), we reevaluated the intestinal sTH17 response in Myd88−/− mice. Consistent with previous studies (Atarashi et al., 2008; Ivanov et al., 2008), we observed normal intestinal TH17 responses in the absence of MyD88 signaling by intracellular cytokine staining of LP cells stimulated with phorbol ester and ionomycin (unpublished data). However, in light of recent findings suggesting that phorbol ester and ionomycin stimulation may exaggerate intracellular IL-17 expression in TH17 cells (Hirota et al., 2011), we sought to address the role of MyD88 in promoting TH17 responses under more physiological conditions. To do so, we stimulated FACS-sorted LP CD3+CD4+ T cells isolated from Myd88−/− animals with antibody to CD3. Myd88−/− mice exhibited decreased intestinal TH17 cytokine responses as determined by ex vivo stimulation of CD3+CD4+-purified cells (Fig. 1 G). To further assess the role of MyD88 in promoting sTH17 responses without ex vivo manipulation, we crossed Rorc(γt)-gfp reporter mice with Myd88−/− mice to generate Rorc(γt)-gfp reporter mice. Consistent with the results obtained with Ilr1−/− mice in vivo and stimulation of LP CD3+CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3 ex vivo, we found reduced frequency of CD4+ Rorc(γt)-gfp+ cells in the intestinal LP of Myd88−/−Rorc(γt)-gfp mice when compared with Myd88+/−Rorc(γt)-gfp littermate mice (Fig. 1 H). In contrast, the frequency of CD4+ Rorc(γt)-gfp+ cells in the intestinal LP of IL-6−/−Rorc(γt)-gfp mice was unimpaired when compared with IL-6+/−Rorc(γt)-gfp littermate mice (Fig. 1 I). Consistently, the production of TH17-associated effector cytokines (IL-17 and IL-22) by FACS-sorted intestinal CD3+CD4+ IL6−/− cells was comparable to that of intestinal CD3+CD4+ T cells from IL-6+/− littermate mice (Fig. 1 I and not depicted). These observations indicate that the homeostatic development of intestinal sTH17 cells does not require IL-6, but is dependent on, IL-1β–IL-1R and MyD88 signaling.

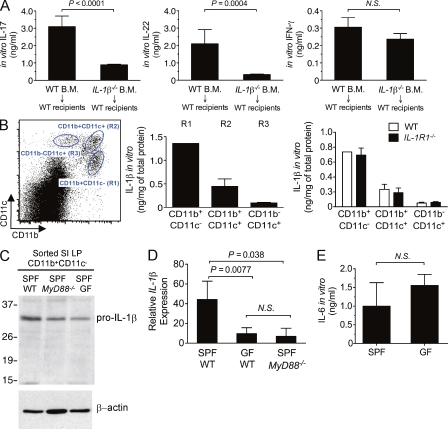

The CD11b+F4/80+CD11c−/low-resident macrophage population is the main source of IL-1β in the small intestine

We next investigated which cellular subset of cells in the intestine is a potential source of IL-1β. To begin to address this question, we generated bone marrow chimera mice by reconstituting lethally irradiated wild-type recipient mice with bone marrow from wild-type or IL-1β–deficient mice. Analysis of the chimera mice revealed that IL-1β produced by hematopoietic cells is required for the induction of intestinal sTH17 responses (Fig. 2 A). Thus, deficiency of IL-1β in hematopoietic cells impaired the production of the TH17-associated effector cytokines, IL-17, and IL-22, but not IFN-γ, by LP cells after in vitro stimulation (Fig. 2 A). Accumulating evidence suggests that LP mononuclear phagocytes are crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and promoting intestinal immunity (Varol et al., 2010). Accordingly, in the intestinal LP, we identified, based on the differential surface expression of CD11c and CD11b, three distinct mononuclear phagocyte populations: CD11b+CD11c− (R1), CD11b+CD11c+ (R2), and CD11b−CD11c+ (R3; Fig. 2 B, left). Next, we examined which subsets of these intestinal phagocytes contribute to steady-state production of IL-1β. To do so, we sorted R1, R2, and R3 populations and assessed intracellular IL-1β protein levels. The R1 population of cells expressed the highest level of IL-1β protein compared to the R2 or R3 subsets (Fig. 2 B, middle). Further flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that the R1 population was CD11b+, F4/80+, MHCII+, CD11c−/low, and CD103int (unpublished data); thus, this population seems to belong to a previously described subset of CD11b+F4/80+ intestinal macrophages (Kamada et al., 2005; Denning et al., 2007). Therefore, these findings indicate that the CD11b+-, F4/80+-, MHCII+-, CD11c−/low-, and CD103int-resident populations are the main source of IL-1β production in the LP of the small intestine.

Figure 2.

The microbiota promotes MyD88-mediated signaling for IL-1β induction in resident intestinal macrophages. (A) Bone marrow chimeras were generated by reconstituting lethally irradiating SPF wild-type recipients with 106 donor bone marrow cells isolated from the indicated mice. Intestinal sTH17 response was assessed at 10 wk after reconstitution. Production of IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ by (106 cells/ml) total LP cells was assessed in the indicated chimera mice after ex vivo stimulation with anti-CD3. The results are shown from one of two independent experiments with five chimera mice per group per experiment. (B, left) Representative FACS dot plot analysis of total intestine LP cells based on CD11b and CD11c expression. (B, middle) R1, R2, and R3 populations were FACS sorted from SPF wild-type mice, and IL-1β levels in total cell lysates from the indicated populations were determined by ELISA and normalized to total protein concentration. (B, right) R1, R2, and R3 subsets were sorted from the LP of the indicated mice, and IL-1β levels were determined. (C) IL-1β mRNA levels measured by real-time RT-PCR in sorted R1 population from indicated mice. (D) Protein extracts form sorted intestinal R1 population from indicated mice were immunoblotted with anti–IL-1β or anti–β-actin (loading control). (E) Total LP cells were isolated from either SPF (n = 20) or GF (n = 9) wild-type mice and the level of spontaneous IL-6 production in overnight cultured supernatant was determined by ELISA. Representative results are shown from one of at least two to three independent experiments. Experiments in panels C and D are representative of two experiments using pooled cells from n = 2–3 mice.

IL-1β induction in intestinal macrophages is mediated via MyD88, but not IL-1R, signaling

The expression of IL-1β is induced by TLR ligands and IL-1β itself can also serve as a positive feedback regulator of this pathway (Dinarello, 2009). To investigate the interaction between commensal bacteria and the host immune system that promotes the induction of IL-1β, R1, R2, and R3 subsets from the LP of wild-type and Ilr1−/− mice were sorted and the protein level of IL-1β was determined. There was no detectable difference in the level of IL-1β between wild-type and Ilr1−/− animals (Fig. 2 B, right), indicating that IL-1β–IL-1R signaling does not regulate the expression of IL-1β in intestinal macrophages. This suggests that induction of IL-1β is upstream of IL-1R signaling. However, LP CD11b+CD11c− cells from SPF Myd88−/− and germ-free (GF) wild-type mice showed decreased levels of pro–IL-1β (Fig. 2 C), suggesting that the interaction between TLR/MyD88 and the commensal microbiota is an essential requirement for the induction of IL-1β in phagocytic cells. In line with this notion, the levels of IL-1β mRNA in the LP were similarly decreased in GF wild-type and SPF Myd88−/− animals as compared with SPF control mice (Fig. 2 D). In contrast, comparable levels of IL-6 were found in the LP of wild-type and GF mice (Fig. 2 E). Collectively, these observations suggest that the microbiota regulates the production of IL-1β in LP phagocytic cells via MyD88, independent of IL-1R signaling, to promote the induction of sTH17 cells in the small intestine.

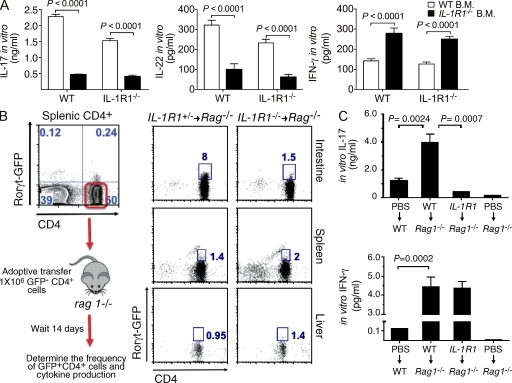

IL-1R signaling on T cells is required for the generation of intestinal sTH17 response

IL-1R1 is ubiquitously expressed on both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells (Dinarello, 2009; Sims and Smith, 2010). To assess the importance of IL-1R1 signaling in various intestinal cellular populations in promoting the generation of sTH17 cells, we generated bone marrow chimera mice. Reconstitution of lethally irradiated recipients, regardless of genotype, with Ilr1−/− bone marrow recapitulated the defective sTH17 response observed in intact Ilr1−/− animals (Fig. 3 A). Thus, deficiency of IL-R1 in hematopoietic cells impaired the production of the TH17-associated effector cytokines (IL-17 and IL-22) by LP cells after in vitro stimulation (Fig. 3 A). The requirement of an intact IL-1R1 signaling pathway in the hematopoietic compartment using bone marrow chimeric mice does not distinguish whether or not direct IL-1R1 signaling on T cells promotes the induction of intestinal sTH17 cells. To this end, we adoptively transferred Ilr1+/− or Ilr1−/− -CD3+CD4+ Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative cells into SPF Rag1−/− recipients (Fig. 3 B, left). Reconstituting Rag1−/− recipients with either Ilr1+/− or Ilr1−/−Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative CD4+ T cells resulted in a similar recruitment and expansion of CD4+ T cells to peripheral organs and frequency of GFP-expressing CD4+ T cells in the spleen and liver (Fig. 3 B, middle). However, despite normal recruitment to and expansion in the intestinal LP, the absence of IL-1R1 on CD4+ T cells selectively impaired the ability of the donor cells to acquire Rorγt expression specifically in the intestinal microenvironment (Fig. 3 B, right). Consistent with diminished numbers of Rorc(γt)-gfppositive cells present in the intestinal LP of Ilr1−/− T cell reconstituted Rag1−/− recipients, in vitro production of IL-17 was also negatively impacted by the lack of IL-1R1 expression on T cells (Fig. 3 C). Thus, these results emphasize that maintaining IL-1β responsiveness in T cells in the intestine is necessary for the development of sTH17 cells.

Figure 3.

IL-1R signaling on T cells is required for the generation of intestinal sTH17 response. (A) Bone marrow chimeras were generated by reconstituting lethally irradiating SPF wild-type or Ilr1−/− recipients with 106 donor bone marrow cells isolated from the indicated mice. Intestinal sTH17 response was assessed at 10 wk after reconstitution. Production of IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ by (106 cells/ml) total LP cells was assessed ex vivo in the indicated chimera mice after stimulation with (soluble, 1 µg/ml) anti-CD3. The results are shown from one of two independent experiments with five chimera mice per group per experiment. (B, left) Experimental procedure for adoptive T cell transfer. (B, right) Representative FACS dot plot analysis of the frequency of CD4+Rorγt-gfp+ cells in various organs at day 14 after adoptive transfer. (C) Production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by (106 cells/ml) total LP cells isolated from adoptively transferred mice (B, right) after ex vivo stimulation with anti-CD3. Data shown are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments with five chimeric mice per group per experiment.

Administration of IL-1β is sufficient to induce the maturation of splenic CD3+CD4+Rorγtnegative cells into intestinal Rorγt-expressing sTH17 cells in GF mice

We next asked whether administration of IL-1β was capable of inducing the presence of sTH17 cells in the LP of GF animals that are largely devoid of these cells (Atarashi et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2008; Ivanov et al., 2008). To assess this, GF mice were injected with rIL-1β or PBS as a control and the presence of sTH17 cells and production of TH17-associated cytokines were assessed in the small intestine. As expected, the production of TH17-associated cytokines IL-17 and IL-22 by LP cells was low in GF mice treated with PBS (Fig. 4 A). Importantly, IL-17 and IL-22 production by LP cells was markedly increased in GF mice treated with exogenous IL-1β when compared with mice treated with PBS (Fig. 4 A). To further interrogate the role of IL-1β in the induction of intestinal sTH17 response, GF wild-type animals were first infused with FACS-purified Thy1.1+/1.2+CD3+CD4+ Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative cells derived from SPF wild-type donors and then treated with PBS or exogenous rIL-1β (Fig. 4 B, top). Administration of rIL-1β selectively induced the donor CD4+ reporter cells to acquire Rorc(γt) expression in the intestinal microenvironment, but not in other peripheral organs, such as the spleen (Fig. 4 B, bottom). These data indicate that the presence of IL-1β is sufficient to induce the differentiation of intestinal sTH17 cells in the absence of microbiota.

Figure 4.

Administration of IL-1β is sufficient to induce the maturation of splenic CD3+CD4+Rorγtnegative cells into intestinal Rorγt-expressing sTH17 cells in GF mice. (A) GF mice were treated every other day for 14 d with either PBS or rIL-1β (1 µg/mouse), and then LP cells were isolated for analysis. Cytokine secretion by total LP cells isolated from either PBS or rIL-1β–treated animals was assessed after ex vivo stimulation with anti-CD3. (B) Experimental scheme for adoptive T cell transfer of sorted splenic Rorγt-GFP−CD4+ T cells into GF recipients. (C) Recipient GF mice were treated every other day for 14 d with either PBS (right) or rIL-1β (right), and then analyzed. Representative FACS plot gated on CD3+CD4+Thy1.1+/1.2+ donor or CD3+CD4+Thy1.1−/1.2+ recipient cells isolated from intestinal LP and spleen from the indicated recipient GF mice are shown. Analysis of Rorγt-GFP staining in recipient CD4+ cells is shown as a control. Representative results are shown from three independent experiments and five mice per group.

The blunted intestinal sTH17 response of GF animals is well-characterized (Ivanov et al., 2008); however, the reason for the impaired sTH17 response that is associated with the absence of commensal microbiota is currently unclear. We provide evidence that the microbiota induces the production of IL-1β in resident macrophages via MyD88 and IL-1β-IL-1R1 signaling is critical for the development of sTH17 cells in the small intestine. Administration of rIL-1β selectively induced the donor reporter cells to acquire Rorc(γt)-expression in the intestinal microenvironment, but not in other peripheral organs, such as the spleen. Thus, the results suggest that the IL-1β/IL-1R axis is not only required, but also sufficient, to drive the development of sTH17 in the intestinal microenvironment. Unexpectedly, IL-6 was not required for the development of intestinal sTH17 cells. Because IL-6 is important for the induction of TH17 cells during inflammatory conditions such as EAE (Korn et al., 2009), the results suggest differential regulation for the development of TH17 cell population which may be explained by differences in the local tissue environment or specific triggers. These results do not rule out that IL-1β acts in concert with other cytokines such as IL-23 that are known to be critical for the development of TH17 cells during inflammatory conditions in nonintestinal tissues (Korn et al., 2009). However, our results clearly indicate that IL-1β, but not IL-6, is induced by the microbiota and critical for the development of intestinal sTH17 cells in vivo.

Our findings also identified MyD88 as a critical mediator for the induction of IL-1β in intestinal macrophages while the expression of pro–IL-1β in intestinal phagocytes was not impaired in IL-R1-deficient mice. These results suggest that MyD88 acts at two distinct steps to regulate the development of sTH17 cells in the intestine. First, MyD88 links the microbiota to pro–IL-1β induction in intestinal macrophages. This mechanism likely involves the TLR-MyD88 signaling pathway given that this appears to be the major innate immune pathway by which the intestinal microflora stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines in host cells (Hasegawa et al., 2010). The second step involves IL-1β/IL-R1/MyD88 signaling in CD4 T cells to drive the development of intestinal sTH17 cells. Collectively, our data suggest that interactions between commensal bacteria and TLR signaling mediated through MyD88 promote IL-1β production in intestinal CD11b+ macrophages, which in turn induces the differentiation of intestinal sTH17 cells. Notably, exogenous IL-1β increased sTH17 cells in the intestine, but not in the spleen, in the absence of microbiota. We do not have an explanation for the latter results, but it suggests that the regulation of Th17 cell differentiation is more complex that originally described and varies in different tissue environments. Because TH17 cells have been suggested to play either a detrimental role in autoimmune disease (McGeachy and Cua, 2008; Ouyang et al., 2008; Korn et al., 2009) or protective role during enteric infection (Ivanov et al., 2009), further understanding the mechanism that regulate the quiescence and the reactivation of these cells may have therapeutic potential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

SPF wild-type and Rag-1−/− mice in C57BL/6 background were originally purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Ilr1−/−, Il1β−/−, and Myd88−/− mice in C57BL/6 background have been previously described (Eigenbrod et al., 2008). Il-6−/− mice in C57BL/6 background were obtained from Dr. Evan Keller, the University of Michigan. Rorc(γt)-gfp mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and crossed to Ilr1−/−, Myd88−/−, or Il-6−/− mice to generate gene-deficient reporter mice. GF wild-type mice in C57BL/6 background were bred and maintained at the Germ-Free Animal Core Facility of the University of Michigan. GF mice were maintained in flexible film isolators and were checked weekly for GF status by aerobic and anaerobic culture. The absence of microbiota was verified by microscopic analysis of stained cecal contents to detect unculturable contamination. All animal studies were performed according to approved protocols by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals.

Cell isolation, adoptive transfer, and administration of IL-1β in vivo.

To isolate Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative cells for adoptive transfer, pan T cells microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) were initially used to enrich total T cells, followed by FACS sorting of CD3+CD4+Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative cells. For adoptive transfer of sorted CD3+CD4+Rorc(γt)-gfpnegative cells into intact GF animals, wild-type Thy1.2+/1.2+ Rorc(γt)-gfp were crossed to Thy1.1 mice (The Jackson Laboratory) and the F1 progeny were used as donors. Donor CD4 cells were distinguished from recipient CD4 cells by flow cytometric analysis for the co-expression of Thy1.1 and Thy1.2 markers. GF mice were treated every other day for 14 d with either PBS or 1 µg/mouse of rIL-1β (PeproTech) i.p., and then intestinal tissue was harvested for analyses. After the last round of injections, there was no evidence of bacterial contamination in the rIL-1β as determined by standard culture conditions.

Isolation and stimulation of LP cells.

Mice were killed and intestines were removed and placed in ice-cold HBSS + 1% heat inactivated FBS + 0.1% Pen/Strep (complete HBSS). After removal of residual mesenteric fat tissue, Peyer’s patches were carefully excised and the intestine was flushed two times with 10 ml complete HBSS. After flushing, the intestine was opened longitudinally and cut into ∼1-cm pieces. The cut pieces were washed two times at 37°C with 30 ml complete HBSS for 5 min each on a magnetic stir plate (600 rpm), followed by incubation with 50 ml 1-mM DTT for 15 min at 37°C with rotation. After DTT treatment, the tissue was then incubated twice with 30 ml 1-mM EDTA at 37°C with rotation. After each incubation, the epithelial cell layer containing the intraepithelial lymphocytes was removed by aspiration. After the last EDTA incubation, the pieces were washed three times in complete HBSS and placed in 30-ml digestion solution (complete HBSS containing Type III Collagenase and DNase I; Worthington). Digestion was performed by incubating the pieces at 37°C for 1–1.5 h with rotation. The digestion product was collected, filtered through a 70-µM cell strainer (BD), and pelleted by centrifugation. The digestion pellet was then resuspended in 4 ml of 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare) fraction and overlaid on 4 ml of 75% Percoll fraction in a 15-ml conical tube. Percoll gradient separation was performed by centrifugation for 20 min at 2,500 rpm at room temperature. LP cells were collected at the interphase of the Percoll gradient, washed once, and resuspended in either FACS buffer or T cell medium. The cells were used immediately for in vitro stimulation, flow cytometric analysis, or cell sorting. Cells purified by flow cytometry from the LP or total LP cells were cultured at the adjusted density of 106 cells per ml with soluble anti-CD3 (1 µg/ml) overnight, and then cytokines in supernatants (IL-22, IL-17A, and IFN-γ) were analyzed by ELISA (R&D Systems). Intracellular cytokine analysis of total LP cells was performed in cells stimulated in vitro with 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 µM ionomycin in the presence of Brefeldin A for 6 h. Surface staining was performed with a corresponding cocktail of fluorescently labeled antibodies (eBioscience) for 30 min on ice; followed by permeabilization with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD), and intracellular cytokine staining was performed with fluorescently labeled anti–IL-17 antibody (eBioscience). Immunoblotting for IL-1β was performed using rabbit anti–mouse IL-1β antibody (R&D Systems).

Real-time PCR analysis.

RNA samples for transcript analysis were isolated from the small intestine or FACS-sorted cells using Total RNA kit I (OMEGA Bio-Tek). Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized from and prepared with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Values were then normalized by the amount of GAPDH in each sample.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Differences between two groups were evaluated using a Student’s t test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Michigan Germ-Free Animal Facility and Flow Cytometry Core and the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center Immunology Core for support; S. Akira and Y. Iwakura for generous supply of mutant mice; S. Koonse for animal husbandry; and G. Chen for review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; G. Nuñez). M.H. Shaw was supported by Lung Immunopathology Training grant T32-HL007517 from the NIH. N. Kamada was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. Y.-G. Kim was supported by training funds from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: M.H. Shaw and G. Nuñez designed the research. M.H. Shaw conducted most of the experiments and analyzed data. N. Kamada performed experiments shown in Fig. 1 (G and I). N. Kamada and Y.-G. Kim performed experiments provided as “unpublished data.” M.H. Shaw and G. Nuñez wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- EAE

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- LP

- lamina propria

- MyD88

- myeloid differentiation factor 88

- Rorγt

- retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor γt

- SFB

- segmented filamentous bacteria

- SPF

- specific pathogen–free

- sTH17 cells

- steady-state TH17 cells

- TLR

- toll-like receptor

References

- Atarashi K., Nishimura J., Shima T., Umesaki Y., Yamamoto M., Onoue M., Yagita H., Ishii N., Evans R., Honda K., Takeda K. 2008. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 455:808–812 10.1038/nature07240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y., Chang S.H., Martinez G.J., Yang X.O., Nurieva R., Kang H.S., Ma L., Watowich S.S., Jetten A.M., Tian Q., Dong C. 2009. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 30:576–587 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning T.L., Wang Y.C., Patel S.R., Williams I.R., Pulendran B. 2007. Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 8:1086–1094 10.1038/ni1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C.A. 2009. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27:519–550 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Chung H., Troy E., Kasper D.L. 2010. Microbial colonization drives expansion of IL-1 receptor 1-expressing and IL-17-producing gamma/delta T cells. Cell Host Microbe. 7:140–150 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Marmon S., Sunshine M.J., Rennert P.D., Choi Y., Littman D.R. 2004. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat. Immunol. 5:64–73 10.1038/ni1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrod T., Park J.H., Harder J., Iwakura Y., Núñez G. 2008. Cutting edge: critical role for mesothelial cells in necrosis-induced inflammation through the recognition of IL-1 alpha released from dying cells. J. Immunol. 181:8194–8198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulen M.F., Kang Z., Bulek K., Youzhong W., Kim T.W., Chen Y., Altuntas C.Z., Sass Bak-Jensen K., McGeachy M.J., Do J.S., et al. 2010. The receptor SIGIRR suppresses Th17 cell proliferation via inhibition of the interleukin-1 receptor pathway and mTOR kinase activation. Immunity. 32:54–66 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J.A., Bouladoux N., Sun C.M., Wohlfert E.A., Blank R.B., Zhu Q., Grigg M.E., Berzofsky J.A., Belkaid Y. 2008. Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity. 29:637–649 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M., Osaka T., Tawaratsumida K., Yamazaki T., Tada H., Chen G.Y., Tsuneda S., Núñez G., Inohara N. 2010. Transitions in oral and intestinal microflora composition and innate immune receptor-dependent stimulation during mouse development. Infect. Immun. 78:639–650 10.1128/IAI.01043-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K., Duarte J.H., Veldhoen M., Hornsby E., Li Y., Cua D.J., Ahlfors H., Wilhelm C., Tolaini M., Menzel U., et al. 2011. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 12:255–263 10.1038/ni.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I.I., McKenzie B.S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C.E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J.J., Cua D.J., Littman D.R. 2006. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 126:1121–1133 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I.I., Frutos Rde.L., Manel N., Yoshinaga K., Rifkin D.B., Sartor R.B., Finlay B.B., Littman D.R. 2008. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 4:337–349 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I.I., Atarashi K., Manel N., Brodie E.L., Shima T., Karaoz U., Wei D., Goldfarb K.C., Santee C.A., Lynch S.V., et al. 2009. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 139:485–498 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada N., Hisamatsu T., Okamoto S., Sato T., Matsuoka K., Arai K., Nakai T., Hasegawa A., Inoue N., Watanabe N., et al. 2005. Abnormally differentiated subsets of intestinal macrophage play a key role in Th1-dominant chronic colitis through excess production of IL-12 and IL-23 in response to bacteria. J. Immunol. 175:6900–6908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T., Bettelli E., Oukka M., Kuchroo V.K. 2009. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27:485–517 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy M.J., Cua D.J. 2008. Th17 cell differentiation: the long and winding road. Immunity. 28:445–453 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R., Preston-Hurlburt P., Kopp E., Stadlen A., Chen C., Ghosh S., Janeway C.A., Jr 1998. MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. 2:253–258 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80136-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W., Kolls J.K., Zheng Y. 2008. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 28:454–467 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims J.E., Smith D.E. 2010. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:89–102 10.1038/nri2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton C., Brereton C., Keogh B., Mills K.H., Lavelle E.C. 2006. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 203:1685–1691 10.1084/jem.20060285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton C.E., Lalor S.J., Sweeney C.M., Brereton C.F., Lavelle E.C., Mills K.H. 2009. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 31:331–341 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beelen A.J., Zelinkova Z., Taanman-Kueter E.W., Muller F.J., Hommes D.W., Zaat S.A., Kapsenberg M.L., de Jong E.C. 2007. Stimulation of the intracellular bacterial sensor NOD2 programs dendritic cells to promote interleukin-17 production in human memory T cells. Immunity. 27:660–669 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varol C., Zigmond E., Jung S. 2010. Securing the immune tightrope: mononuclear phagocytes in the intestinal lamina propria. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:415–426 10.1038/nri2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]