Abstract

We examined the relationship between sedation and orthostatic hypotension, two central side effects and ABCB1 transporter-mediated efflux for a set of 64 launched drugs that are documented as histamine H1 receptor antagonists. This relationship was placed in the context of passive diffusion (estimated using LogP, the octanol/water partition coefficient), receptor affinity, and the adjusted therapeutic daily dose, in order to account for side effect variability. Within this set, CNS permeability was not dependent on passive diffusion, as no significant differences were found for LogP and its pH-corrected equivalent, LogD74. Sedation and orthostatic hypotension can be explained within the framework of ABCB1-mediated efflux and adjusted dose, while target potency has less influence. ABCB1, an antitarget for anti-cancer agents, acts in fact as a drug target for non-sedating antihistamines. An empirical set of rules, based on the incidence of these two side-effects, target affinity and dose was used to predict efflux effects for a number of drugs. Among them, azelastine and mizolastine are predicted to be effluxed via ABCB1-mediated transport, whereas aripiprazole, clozapine, cyproheptadine, iloperidone, olanzapine, and ziprasidone are likely to be non-effluxed.

Keywords: ABCB1, LogP, data mining, MRTD, CNS permeability, antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics

1 Introduction

The process of drug discovery is no longer the domain of the pharmaceutical and biotech industry, as it transitions to an integrated academic-industrial partnership. It remains a highly competitive arena, where appropriate, on-time and well-informed decisions can significantly alter the chance of success of new products (drugs) on the market. This process rests on clinical, scientific and economic reasons: Marketing and clinical trial studies are used to decide the fate of drug candidates, whereas scientific factors are used in earlier phases to prioritize candidates. In the scientific arena, as well as in the intellectual property (economic) aspects, cheminformatics and bioinformatics are likely to play an increasing role [1]. The notion of “prior art” covers not only the specifics of intellectual property, but also in-depth coverage of the properties of small molecules, ranging from target- and antitarget- related bioactivities [2] to physico-chemical and pharmacokinetic properties, metabolism, acute and chronic toxicity, and other clinically relevant properties.

Public access to large amounts of information, by means of the open access policy for databases and papers, is likely to level the playing field and enable academia to contribute in a meaningful manner to drug discovery. For example, the NIH (National Institutes of Health) Molecular Libraries and Imaging initiative (MLI) [3] has sponsored the assembly of a small-molecule chemical library, known as the MLI Small Molecule Repository, or MLSMR, which is currently being tested on an increasing number of assays. As of mid-November 2009, the keyword “MLSMR” in PubChem [4] retrieves 355,260 molecules and 1,458 bioassays. Funded by the Wellcome Trust, the European Bioinformatics Institute offers an open access medicinal chemistry database, ChEMBLdb [5], which covers 440,055 unique molecules and 1,936,969 bioactivities (on 3,622 unique protein accession numbers) from 26,299 papers.

Since access to information is no longer the bottleneck in probe, lead and drug discovery, we anticipate that successful data mining and integration [6], combined with predictive technologies and intertwined with experiments, are likely to become the building blocks of future drug discovery. Discovery scientists are thus expected to familiarize themselves with a multiplicity of sources and data formats, and are likely to have to piece together the information related to their areas of interest. Focus is shifting from data acquisition, which is being enabled by public access databases supported by fast and efficient search engines, to problem-solving skills, knowledge management and data integration.

To examine how transporter-mediated efflux influences CNS (central nervous system) side effects, we analyze an integrated dataset that spans 64 launched drugs sharing a common thread: Documented activity on the histamine H1 receptor (H1R) [7] in a clinical setting. Our initial aim was to evaluate the relationship between H1 antagonism and sedation, an undesired CNS effect. The dataset was expanded to cover not only “antihistaminic” drugs, but also other categories such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, which include known H1 antagonists. The binding affinity of these drugs to other drug targets is also discussed in the context of another CNS adverse effect, orthostatic hypotension.

Central to this discussion is the influence of the efflux transporter ABCB1, (ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1), also known as Multidrug resistance protein 1 or P-glycoprotein [8, 9]. The relationship between CNS penetration and ABCB1-mediated efflux is placed in the context of receptor affinity, some pharmacokinetic properties and the adjusted therapeutic dose, in order to better understand side effect variability. These and other properties, e.g., the effect on other drug targets, may have to be taken into account when studying CNS-related adverse effects such as sedation and orthostatic hypotension. We also show that therapeutic use can shift the attribute of target to antitarget and vice-versa for both H1R and ABCB1.

2 Drugs That Block H1 Receptors: An Overview

2.1 Antihistamines

The discovery of histamine, its role in the immunology of hypersensitivity and the identification of the H1R involved some of the greatest scientific minds of the time, including five Nobel laureates, and led to the development of a completely new conceptual framework, which included (among others) the notions of anaphylaxis, allergy, and pharmacological receptors [10]. Since the first (1942) clinical introduction of the antihistamine Antergan, or N-benzyl-N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]aniline by Rhône-Poulenc (now Sanofi-Aventis) [10], a variety of antihistamines have become widely used in the treatment of allergy-related conditions such as rhinitis, conjunctivitis and urticaria. The dataset that is subject to this analysis includes 23 antihistamines (see Table 1 and Supporting Information), launched between 1949 (chlorpheniramine) and 2007 (levocetirizine). Cetirizine, an antihistamine launched in 1987, was not included in this study, since we discuss its more potent levo isomer.

Table 1.

Drug information data for 64 drugs that block the histamine H1 receptor.

| Drug Name | First Launcheda | Therapeutic Category | Sedative Effect Incidence | Orthostatic Hypotension Incidence | H1R affinityb | Alpha1A affinityb | DoseAdjc | ABCB1 Efflux |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| amitriptyline | 1960 | antidepressant | Medium | High | 9.3 | 7.9 | 0.519 | No |

| chlorpheniramine | 1949 | antihistaminic | High | Low | 9 | 0.058 | No | |

| chlorpromazine | 1953 | antipsychotic | High | High | 8.2 | 0.419 | No | |

| clemastine | 1967 | antihistaminic | High | medium | 8.585 | 0.003 | No | |

| clozapine | 1972 | antipsychotic | High | High | 9.2 | 8.1 | 0.723 | |

| cocaine | 1860 | anesthetic | No | No | 5.67 | 5.68 | 0.281 | |

| desipramine | 1962 | antidepressant | Medium | High | 7.12 | 7 | 1.360 | No |

| diphenhydramine | 1951 | antihistaminic | High | medium | 7.9133 | 0.294 | No | |

| doxepin | 1969 | antidepressant | High | medium | 9.75 | 7.6289 | 0.966 | No |

| imipramine | 1957 | antidepressant | Medium | High | 7.6138 | 7.4949 | 0.257 | No |

| loratadine | 1988 | antihistaminic | Low | No | 7.7959 | 0.005 | Weak | |

| nortriptyline | 1965 | antidepressant | Medium | High | 8.0325 | 7.2596 | 0.243 | No |

| pimozide | 1970 | antipsychotic | Medium | Low | 6.881 | 6.704 | 0.002 | Weak |

| protriptyline | 1967 | antidepressant | Low | High | 7.22 | 0.221 | Weak | |

| risperidone | 1993 | antipsychotic | Medium | Low | 7.4815 | 8.5528 | 0.039 | No |

| fexofenadine | 1996 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8 | 0.745 | Yes | |

| trazodone | 1972 | antidepressant | High | medium | 6 | 9.5513 | 1.307 | No |

| citalopram | 1989 | antidepressant | Low | medium | 6.4559 | 0.423 | No | |

| dosulepin | 1962 | antidepressant | High | medium | 8.699 | 6.3778 | 1.937 | |

| lofepramine | 1977 | antidepressant | Medium | medium | 6.4437 | 7 | 0.002 | |

| maprotiline | 1982 | antidepressant | High | medium | 8.7773 | 9.854 | 0.973 | No |

| mianserin | 1976 | antidepressant | High | Low | 9.2454 | 0.097 | ||

| acrivastine | 1988 | antihistaminic | No | No | 7.5 | 0.551 | Yes | |

| astemizole | 1983 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8.58 | 0.006 | Yes | |

| azelastine | 1986 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8.1675 | 0.027 | ||

| levocetirizine | 2007 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8.699 | 0.013 | Yes | |

| ketotifen | 1981 | antihistaminic | High | High | 9.5086 | 0.013 | ||

| oxatomide | 1981 | antihistaminic | High | N/A | 7.699 | 0.087 | ||

| promethazine | 1951 | antihistaminic | High | medium | 9.6198 | 0.088 | ||

| orphenadrine | 1957 | antiparkinsonian | Medium | Low | 7.9586 | 14.424 | ||

| bromperidol | 1973 | antipsychotic | No | Low | 6.155 | 7.1 | 0.059 | |

| prochlorperazine | 1957 | antipsychotic | Medium | medium | 7.7228 | 7.6216 | 0.024 | |

| asenapine | 2009 | antipsychotic | High | Low | 9 | 8.92 | 0.001 | |

| diphenylpyraline | 1955 | antihistaminic | High | N/A | 8.0757 | 0.001 | ||

| mebhydrolin | 1954 | antihistaminic | High | N/A | 7.1192 | 7.443 | ||

| terfenadine | 1981 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8.699 | 0.420 | Yes | |

| aripiprazole | 2002 | antipsychotic | High | Low | 7.2147 | 7.244 | 0.004 | |

| desloratadine | 2001 | antihistaminic | No | No | 9.4 | 0.015 | Yes | |

| quetiapine | 1997 | antipsychotic | High | medium | 8.35 | 7.0269 | 0.531 | No |

| cyproheptadine | 1965 | antihistaminic | High | High | 10.2218 | 7.4 | 0.017 | |

| olanzapine | 1996 | antipsychotic | High | High | 8.1549 | 7.7212 | 0.022 | |

| thiethylperazine | 1960 | antiemetic | High | Low | 7.6021 | 8.699 | 0.166 | |

| ziprasidone | 2001 | antipsychotic | High | medium | 7.33 | 8 | 0.004 | |

| bromazine; bromodiphenhydramine | 1954 | antihistaminic | High | medium | 8.8861 | N/A | ||

| cyclobenzaprine | 1977 | muscle relaxant | High | medium | 8.8288 | 0.042 | No | |

| propiomazine | 1959 | hypnotic | High | Low | N/A | 0.153 | ||

| mirtazapine | 1994 | antidepressant | High | Low | 8.7959 | 0.212 | ||

| hydroxyzine | 1956 | antihistaminic | High | Low | 8.699 | 0.480 | No | |

| epinastine | 1994 | antihistaminic | No | No | 8.9 | 0.165 | Yes | |

| nefazodone | 1994 | antidepressant | High | medium | 6.4318 | 7.7892 | 0.018 | No |

| cyclizine d | 1953 | antiemetic | Medium | medium | 7.2 | 2.004 | ||

| ebastine | 1990 | antihistaminic | Low | No | 8 | 0.004 | Weak | |

| olopatadine | 1997 | antihistaminic | Medium | N/A | 8.284 | 0.031 | Weak | |

| fluphenazine | 1959 | antipsychotic | Medium | Low | 7.7934 | 8.1905 | 0.018 | |

| benztropine | 1954 | antiparkinsonian | No | No | 8.9586 | 0.003 | ||

| mizolastine | 1998 | antihistaminic | No | No | 9.1 | 0.004 | ||

| 2-Hydroxyimipramine | 1957 | antidepressant | High | N/A | N/A | 0.142 | ||

| melperone | 1972 | antipsychotic | Medium | Low | 6.2366 | 6.74 | 6.509 | |

| iloperidone | 2009 | antipsychotic | Medium | High | 7.91 | 7.44 | 0.034 | |

| nomifensine | 1972 | antidepressant | No | N/A | 5.57 | 4.747 | ||

| carbamazepine | 1963 | anticonvulsant | High | medium | 4.125 | 18.081 | No | |

| loperamide | 1976 | antidiarrheal | No | No | 5.699 | 0.000 | Yes | |

| perphenazine | 1957 | antipsychotic | High | Low | 8.0881 | 8 | 0.014 | No |

Indicates the year the drug was first launched world-wide.

Receptor affinity values are expressed as the negative logarithm of the molar concentration

DoseAdj is expressed in μM/kg-body weight/day.

The H1R binding affinity for cyclizine is from guinea-pig brain membranes; all other data is from human receptor assays.

The link between cerebral H1R occupancy and the sedative properties of psychotropic drugs [11], recognized by Schwartz et al. in 1979, helped associate sedation, one of the “most frequent and troublesome [CNS] adverse effects” [12] of antihistamines, with H1 antagonism. Now referred to as “first generation” antihistamines [13], these drugs have since been identified as penetrating the CNS, i.e., crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and binding to the central H1R – which effectively makes central H1R an antitarget, as opposed to the peripheral H1R (target). A new class of antihistamines, now referred to as “non-sedating”, emerged on the market soon thereafter (1983 and later – see Table 1). Human positron emission tomography studies confirmed that H1-receptor occupancies of the second-generation antihistamines were relatively lower than those of the sedating antihistamines [14], which clearly indicated lower CNS penetration for these drugs.

In addition to antihistamines, other therapeutic categories of drugs bind to H1Rs and are associated with sedation. Two other major classes, antipsychotics and antidepressants, are briefly introduced below.

2.2 Antipsychotics

Starting with the observation that chlorpromazine causes “emotional indifference” in the early 1940s, “neuroleptic” (antipsychotic) drugs were launched in 1953 and later. All sixteen antipsychotics examined here (see Table 1) are known to bind to the H1R with affinities below 1 μM, of which seven are better than 10 nM. While the exact mechanism of action of these drugs in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders is not fully understood, most clinicians agree that the sedative and sleep-inducing (H1R-mediated) effects associated with these drugs are beneficial, at least in those cases where suicidal tendencies are manifest [15].

2.3 Antidepressants

Antidepressant therapy emerged with the launch of imipramine (1957), the first in a new class, now referred to as “tricyclic antidepressants”, which includes amitriptyline, dosulepin and several of their active metabolites (e.g., desipramine, nortriptyline) – see Table 1. Of the more recent antidepressants, only citalopram, mirtazapine and nefazodone are discussed. Other antidepressants are either inactive at the H1R (venlafaxine, adinazolam), or their Ki values are between 5 and 23 μM [16], which is less likely to be associated with sedation (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine and tomoxetine). Indeed, the lack of sedation as side-effect is desirable in most antidepressants since it enables humans to engage in otherwise normal activities such as operating machinery [12].

2.4 Other therapeutic categories

Other drugs known to bind to the H1R include two antiemetics (thiethylperazine and cyclizine) initially developed as antihistamines; the local anesthetic cocaine; the anticonvulsant carbamazepine; the antidiarrheic loperamide; orphenadrine, an antimuscarinic developed from antihistaminic drugs, and benztropine – both used in Parkinson’s disease; cyclobenzaprine, which is related to tricyclic antidepressants but is primarily used for its muscle relaxant properties; and propiomazine, an antipsychotic derivative used as hypnotic.

2.5 H1 antagonism and efflux via ABCB1

Several efflux pumps, including ABCB1, have been shown to play an important role in the therapeutic effect of CNS drugs and their (lack of) permeability across the BBB [17]. Some efflux pumps, e.g., ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCC2, and ABCG2, have been shown to influence oral absorption and disposition of a wide variety of drugs [18]. In particular, the interplay between intestinal ABCB1 and the 3A4 isozyme of the cytochrome P450 system (CYP3A4) is responsible for the poor oral bioavailability of a number of drugs [19]. Furthermore, elevated expression levels of ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCG2 and perhaps other ABC efflux transporters in human cancer cells have been found to lead to multidrug resistance [20], which in turn correlates with patient outcome in a number of cancers [21]. These studies point to the role of ABCB1 and other ABC transporters as antitargets. The appropriate study of these transporters allows us to better understand drug absorption, to evaluate cancer patients with respect to their responsiveness to chemotherapy, as well as their susceptibility to side effects. By gaining further insight into their substrate preferences, we can also examine the role of efflux pumps as drug targets, e.g., the case of non-sedating antihistamines, first suggested by Chishty et al [22]. The principle of minimal hydrophobicity [23], evaluated via LogP - the octanol/water partition coefficient [24], was explored in relationship to the CNS penetration of antihistamines [25]: For LogP values below zero, or above four, it was suggested that H1 drugs lack entry to the brain. However, efflux by ABCB1 can only result in noticeable effects when the rate of active transport for a compound is substantial relative to the passive diffusion rate [17]. We therefore examine the role of LogP in relationship to CNS effects and the ABCB1-mediated efflux, earlier discussed for antihistamines [26].

3 Data collection

We critically examine the relationship between CNS side effects and transporter-mediated efflux, by linking sedation, antagonism at the central H1R and active efflux, already rationalized with respect to antihistamines [27], which was suggested as a topic for comprehensive data mining [28]. Key to our effort was the evaluation of two CNS-related side effects: sedation and orthostatic hypotension. Their qualitative evaluation was based on several on-line resources [29]. The following synonyms were used interchangeably: “sedation”, “drowsiness”, “sedative effect”, “somnolence”, and the impaired ability to operate machinery, as well as “non-sedating”, in order to annotate the sedative effect; “orthostatic”, “symptomatic”, or “postural” hypotension, respectively, or “lower blood pressure” when enumerated as one of the cardiovascular side-effects, in order to annotate orthostatic hypotension. The qualitative evaluation of these adverse effects was related to their incidence, i.e., the rate of occurrence of these symptoms over a period of time (typically for the duration of clinical trials), taken from tabulated information wherever possible (quantitative evaluations were systematic in DailyMed and FASS [29]).

Target data compiled in Table 1 originates from the WOMBAT-PK database [30]. Target data collection was primarily based on three on-line sources [31], which serve as on-line repositories for receptor interaction data. Additional information was derived from peer-reviewed literature [16, 32–38]. The difficulty when reconciling data from various, non-homogenous sources, was to reduce multiple bioactivity data (e.g., determinations made with different radio-labeled ligands) into a single number. Where available, priority was given to expert-curated data, e.g., from IUPHAR-DB [39]. Although every reasonable attempt was to present data as accurately as possible, we caution the reader not to use this information as substitute for medical advice. Indeed, individual drug formulations, different therapeutic regimens, dietary habits as well as phenotypic variability can significantly alter the response to a particular medicine; therefore a physician should be consulted with respect to particular situations.

4 The relationship between some CNS adverse effects, dose and efflux

Antihistamines are often reported to cause drowsiness (sedation), which is an undesired effect that is generally more severe in “first generation” antihistamines [13]. The relationship between CNS penetration and central adverse effects can be extended not only to other drugs that block H1 (i.e., “sedative”), but also to other CNS side-effects such as orthostatic hypotension, which are often associated to alpha-1A adrenergic receptor blockade [40]. Since ABCB1-mediated transport is likely to explain the lack of sedation via CNS efflux (absence of brain penetration) for non-sedating H1 antagonists [26], we decided to falsify this observation in a Popperian sense [41]: Non-effluxed drugs that are BBB permeable and display central H1R occupancy [14] should have a sedative effect. This observation should hold true for other, non-H1 mediated central side-effects, such as hypotension, and should not be driven by passive diffusion.

4.1 CNS permeability and passive diffusion

The first objection one could formulate is that favorable LogP plays an important role in the lack of CNS penetration for those drugs that are not associated with sedation or hypotension. However, as shown in Table 1 (and Supporting Information), except for two drugs that lack ABCB1 annotation (discussed in section 5), all drugs that are not CNS permeable (“BBB-“) are either effluxed (eight) or weakly effluxed (two). Forty-four measured LogP values further highlight the importance of ABCB1-mediated efflux by showing a rather similar distribution for the CNS permeable (BBB+) drugs (median LogP = 4.24; StdDev = 0.96; N = 35) compared to BBB- drugs (3.93 ± 1.42; N = 9). This phenomenon is not influenced by charge / pH correction either, since LogD74, the ion-corrected octanol/water distribution coefficient at pH = 7.4 shows a similar trend: Median LogD74 = 2.67; StdDev = 1.04 (N = 33) for BBB+ drugs, vs. 2.78 ± 1.67 (N = 9) for BBB- drugs, respectively. The same lack of statistical significance is observed when comparing measured LogP and LogD74 distributions for those drugs annotated for sedative and orthostatic hypotension respectively (data not shown).

Ter Laak et al. clearly established that lipophilicity does not account for the (non)-sedative effects of antihistamines [25]. However, the role of ABCB1 in brain penetration was convincingly demonstrated only 2 years later by Schinkel et al. [42], who showed that brain penetration of several drugs that are ABCB1 substrates is significantly increased in mice lacking the ABCB1 gene, compared to wild type. Yet the concept of favorable LogP optimization in order to avoid CNS permeability (hence sedation) for antihistamines continues to be cited as an example of medicinal chemistry success in drug development [43], albeit in the context of ABCB1 substrate optimization [44], even though it is unlikely that such information was utilized during the drug discovery process before 1996.

To summarize, these data support the observation that passive diffusion, as estimated by LogD74 and LogP, is not the major determinant for the absence or presence of central adverse effects. They further point in the direction of ABCB1-mediated transport. Our sixty-four drugs dataset was annotated for ABCB1 efflux according to literature data [45–48]. Of thirty-three well-annotated drugs, twenty are not effluxed, i.e., they do not exhibit polarized transport [45]; another five are weakly effluxed, meaning that the limit for the permeability ratio assay is near 2, suggesting borderline values; finally, eight drugs are unambiguous, or transported substrates. Thus, ABCB1-mediated efflux was established as the first parameter in our reference framework.

4.2 Dose adjustment

The second parameter relates to dose. It is based on MRTD, the maximum recommended therapeutic daily dose [49], converted from mg/daykg-bw (kg body-weight) to μM/day/kg-bw, MRTD(μM), and adjusted according to Eq. (1):

| Eq (1) |

where %Oral is the percent oral bioavailability and %PPB is the percent of drug bound to plasma proteins, as compiled in WOMBAT-PK [31] - see also Table 1 and Supporting Information. The adjusted dose, DoseAdj, rather than MRTD(μM), is likely to reflect the fraction of the maximum daily dose responsible for CNS penetration (and likely to cause side-effects) and available for interacting with drug targets. Summerfield et al. showed that CNS efficacy is influenced by lipophilicity, active transport and the unbound drug fraction, which was further differentiated into blood and brain homogenate fractions [50]. These factors influence the amount of free drug that is likely to be responsible for sedation and other CNS effects. Since we already discussed the effect of LogP and LogD74, and because we lack data to differentiate the fraction unbound between brain and blood, we utilized (1 - %PPB) in Eq(1) as a surrogate measure. This is further reflected in the adjusted dose.

MRTD(μM) is related to oral bioavailability for all examined drugs, i.e., it was not taken from intravenous or other therapeutic formulations, further supporting the need for dose adjustment. Because they cannot be used, or dosed, in intra-venous formulations, the absolute oral bioavailability was not available for several drugs. However, an estimate of DoseAdj was derived using a lower-bound value for %Oral, derived as follows: The fraction of drug excreted unchanged in urine following oral administration (higher than 60%) was used for olopatadine. The fraction of radioactive dose excreted in urine for the primary metabolite was used for desloratadine, cyproheptadine, hydroxyzine and ebastine. Finally, 7.77% of the MRTD(μM) of imipramine and 100% for “oral” bioavailability were used for the active metabolite, 2-hydroxy-imipramine. The 7.77% value represents the fraction of the 100 mg imipramine daily dose converted at steady state to 2-hydroxy-imipramine, as opposed to desipramine (38.96%) and 2-hydroxy-desipramine (22.21%), respectively [51]. Except for cocaine (0.76 hours), none of the drugs reported here had a plasma half-life of less than one hour (data not shown).

From the distribution of DoseAdj across this dataset, the cut-off value of 0.1 was introduced to separate “low dose” (0.1 μM/kg-bw/day or less; N = 31) from “high dose” (above 0.1; N = 32), respectively. There was no statistical significance when comparing MRTD(μM) and DoseAdj distributions for drugs having high incidence of sedation (N = 31) and hypotension (N = 12), to those lacking such CNS side-effects (N = 14 and 15), respectively (data not shown). This further substantiates the role of ABCB1-mediated efflux in this context.

4.3 CNS side effects and efflux

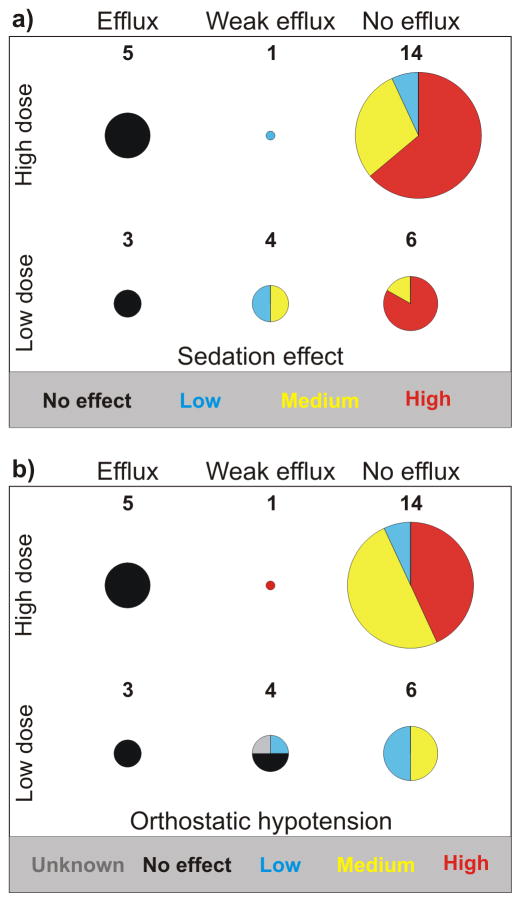

A convergent picture emerges for both sedation and orthostatic hypotension when considering the framework defined by efflux and dose (see Figure 1). Namely, that the eight drugs that are effluxed are both non-sedating and lack hypotension as side-effects. However, it should be noted that under “overdose” conditions, some of the non-sedating, effluxed antihistamines can cause somnolence, presumably by penetrating the brain and overloading the ABCB1 efflux capacity. For example, patients taking levocetirizine are instructed to not exceed 5 mg per day, because of the increased risk of somnolence at higher doses [52]. With respect to alpha-1A adrenergic activity, there was no publicly available information for the eight efflux drug. However, four of the effluxed drugs block alpha-1A adrenergic receptors; these include astemizole and epinastine, which have sub-micromolar alpha-1A potency [53].

Figure 1.

The relationship between efflux, dose and CNS side-effects: a) sedation; b) orthostatic hypotension. Red and yellow indicate a high and medium incidence of the side-effect, blue indicates a low incidence, while black indicates the documented absence of the side-effect. Grey indicates that the incidence of the side-effect is unknown.

Drugs that are not effluxed are more likely to cause side-effects with medium-to-high incidence, both with respect to sedation and hypotension. Indeed, twenty-seven drugs (most of them antidepressants and antipsychotics) are quite likely to have medium-to-high incidence for both sedation and orthostatic hypotension. Within this subset, seventeen have receptor affinity better than 1 μM for both H1R and alpha1A. Furthermore, non-effluxed drugs that have low dose are also annotated with alpha-1A affinity better than 0.4 μM (three of them), while five have H1 affinity better than 50 nM. Taken together, these observations suggest that these two CNS side-effects are more likely to be caused by a direct drug-target interaction in the brain. However, we found no significant correlation (r2 < 0.4) between H1R potency and any of the following target activities (see also Supporting Information): serotoninic receptor 5-HT2A (N=30), serotoninic re-uptake transporter 5-HTT (N=16), norepinephrine re-uptake transporter NET (N=17), muscarinic receptor M1 (N=24), dopaminic receptor D2 (N=24), inward rectifier potassium channel hERG (N=22), and alpha-1A (N=28).

The sedative effect is similar for all non-effluxed drugs with H1R affinity better than 1 μM; indeed, all but one drug associated with sedation display H1R affinity better than 1 μM. The exception, carbamazepine, has a rather low H1 affinity (70 μM), but has the highest MRTD(μM) in our dataset (113 μM/day/kg-bw, adjusted to 18.08 μM/day/kg-bw), suggesting that over-abundance in the CNS may compensate for its lack of H1 potency. The possibility that sedation, in the case of carbamazepine, may be not be mediated by H1R, but perhaps via GABA-A (gamma-amino-butyric acid subtype A) receptors, should not be excluded.

The influence of dosage for the two central side effects is clear in the case of the five weakly effluxed drugs: These molecules show at least low sedative effect even at low dosage, while orthostatic hypotension is observed only at high dosage. By contrast, ABCB1-mediated efflux does not influence peripheral side effects such as Torsade de Pointes, a cardiac toxicity side-effect mediated (in part) by the inward rectifier potassium channel hERG (N=36; data not shown - see Supporting Information).

5 Predicting efflux based on CNS adverse effects and dose

Although H1 antagonism is the common theme for this dataset, there is a wide range and diversity of targets that appear to be characteristic for each drug category. The number of annotated targets alone (from WOMBAT-PK [30]) discriminates between antihistamines, antidepressants and antipsychotics (Table 2). As a therapeutic category, antihistamines are less likely to interact with other targets (5 ± 5 targets), compared to antidepressants (13 ± 6) and the more promiscuous antipsychotics (20 ± 7), respectively. We note that, in this dataset, “antidepressants” refers primarily to tricyclic drugs, and is less reflective of the more recent (hence “cleaner”) monoamine transporter inhibitors.

Table 2.

Number of targets distribution for the main classes of drugs that block the H1R.

| Statisticsa | Anti- histaminic | Anti- depressant | Anti- psychotic | Othera |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 23 | 16 | 16 | 9 |

| 25% | 4 | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Median | 5 | 13 | 20 | 9 |

| 75% | 8 | 17 | 22 | 15 |

| StdDev | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

The statistics include the 25%, 50% (median), and 75% distribution moments.

These therapeutic categories are enumerated in section 2.4

Absence of sedation may be central to the quality of antihistamines, but the ability to operate machinery and otherwise experience a state of mental alertness are likely to be desirable properties for all therapeutic categories in discussion. To genuinely test our Popperian hypothesis, that ABCB1-mediated efflux is the major determinant for these central side effects, we queried the relationship between CNS side-effects incidence (for sedation and hypotension), or the lack of these side-effects, H1 and alpha-1A binding affinity (where available), and DoseAdj. An empirical set of rules, defined from – and quite likely limited to – this data set, was derived, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Side-effect based prediction rules for ABCB1 efflux. See Supporting Information for the actual predictions.

| Receptor Binding | Incidence | CNS Side Effect | Dose Adj | Efflux Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | High | Sedative | Any | No |

| Any | Medium | Sedative | Any | No |

| Any | High | Ort. Hypot. | Any | No |

| Any | Medium | Ort. Hypot. | Any | No |

| Any | Low | Ort. Hypot. | Any | No |

| Any | Low | Sedative | Any | No or Weak |

| ≤ 1 μM | No | Sedative | Any | Yes |

| ≤ 1 μM | No | Ort. Hypot. | Low | Yes or Weak |

| ≤ 1 μM | No | Ort. Hypot. | High | Yes |

| > 1 μM or unknown | No | Sedative | Any | NP |

| > 1 μM or unknown | No | Ort. Hypot. | Any | NP |

These side-effect based prediction rules were applied to the remainder of our dataset (31 drugs), in order to predict their likelihood of being effluxed, or not. Two drugs are predicted to be effluxed: azelastine and mizolastine. These are not associated with sedation, even though they have high H1R affinity (see Table 1 and Supporting Information). Both are antihistamines, though the former is clinically used only for ophthalmic applications. Despite our best efforts, we could not find any annotations relating these two drugs to ABCB1-mediated efflux.

Starting from the incidence of both CNS side effects, we further predict a large number of drugs as being non-effluxed. These include aripiprazole, bromazine, clozapine, cyproheptadine, dosulepin, iloperidone, ketotifen, lofepramine, olanzapine, orphenadrine, prochlorperazine and ziprasidone. Among them, cyproheptadine and ketotifen – both chemically related to tryciclic antidepressants, are “first generation” antihistamines. With its ability to block with high affinity no fewer than five serotonin receptors in addition to 14 other targets, cyproheptadine is indicated in the management of migraine, in addition to its clinical use for the symptomatic relief of allergic conditions such as urticaria and angioedema. Ketotifen, primarily formulated as solution for ophthalmic use, is a non-competitive H1R and muscarinic receptors antagonist that can also act as mast cell stabilizer.

6 Conclusions

Two different central side effects can be explained within the same reference framework, namely ABCB1-mediated efflux (based on permeability ratio assays) and adjusted dose. Except for slight differences noted for low doses, this framework is descriptive for both sedation and orthostatic hypotension. It explains how ABCB1, an antitarget where anti-cancer chemotherapeutic agents are concerned, can de facto become a drug target for, e.g., non-sedating antihistamines. It could also become a target for those drugs that have a primary mode of action outside the CNS but have a high incidence of CNS-related adverse events. The potency of individual drugs for particular targets is found to be significant for those non-effluxed drugs that have high potency, and higher incidence of the side effects. It does not emerge as the dominant parameter compared to efflux, since several of the effluxed drugs lack side effects despite high affinity for H1 and alpha-1A receptors. However, it is likely to be relevant for peripheral, e.g. cardiovascular [54] targets. Indeed, ABCB1-mediated efflux does not relate to the ability of drugs to cause cardiac toxicity via Torsade de Pointes.

Therapeutic use may switch attribute from target to antitarget, as is the case for H1R antagonists for which absence of central H1R perturbation is desired (e.g., absence of sedation). Vice-versa, ABCB1 substrates that are effluxed from the brain can clinically benefit from this property, which is now established as an attribute for non-sedating antihistamines. This effectively makes ABCB1 a drug target, another therapeutic shift compared to its classical “antitarget” designation where antineoplastic agents are concerned [55].

In a Popperian effort to falsify our hypothesis, we showed that LogP and LogD74, while necessary for passive BBB permeability, do not have a significant influence on CNS side effects, confirming earlier observations [25, 50], nor do they influence the incidence of sedation and orthostatic hypotension. We also showed that (adjusted) dose alone is not enough to explain their incidence. Finally, we derived an empirical set of rules, based on the incidence of sedation and orthostatic hypotension, target affinity and dose to predict efflux effects for 31 drugs. Among them, the antihistamines azelastine and mizolastine are predicted to be effluxed via ABCB1-mediated transport. Several other drugs, including aripiprazole, bromazine, clozapine, cyproheptadine, dosulepin, iloperidone, ketotifen, lofepramine, olanzapine, orphenadrine, prochlorperazine and ziprasidone are not likely to be effluxed.

Loperamide, an antidiarrheic drug that targets intestinally located mu-type opioid receptors, thus slowing gut motility, lacks both intestinal as well as BBB permeability due to the CYP3A4 / ABCB1 combination [19], since it is a substrate for both. However, when co-administered with ABCB1 inhibitors such as qunidine and ritonavir, it may cross the intestinal and blood-brain barriers, being associated with respiratory depression [56]. Therefore, one has to continuously examine drug-target interactions, in particular with respect to drug-drug interactions, some of which may relate to the inhibition of efflux.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Boyer (AstraZeneca R&D) for discussions related to MRTD and for alpha-1A adrenergic receptor blockade information. We thank Prof. Henk Timmerman (Vrije Universteit Amsterdam) for suggesting this study and for his in-depth knowledge on H1 antagonism. Dr. Joe Polli (GlaxoSmithKline) is acknowledged for clarifying the efflux of pimozide. This study was supported, in part, by NIH grant 5U54MH084690-02 and by the University of New Mexico sabbatical leave program (TIO).

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this article is available on the WWW under www.molinf.com

References

- 1.Olsson T, Oprea TI. Curr Opin Drug Discov & Develop. 2001;4:308–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaz R, Klabunde T, editors. Antitargets. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin CP, Brady LS, Insel TR, Collins FS. Science. 2004;306:1138–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.1105511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.PubChem is available online at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- 5.Chembldb is available online from the European Bioinformatics Institute, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembldb/index.php

- 6.Oprea TI, Tropsha A. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2006;3:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita M, Fukui H, Sugama K, Horio Y, Ito S, Mizuguchi H, Wada H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11515–11519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juliano RL, Ling V. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;455:152–162. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CJ, Chin JE, Ueda K, Clark DP, Pastan I, Gottesman MM, Roninson IB. Cell. 1986;47:381–389. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel MB. Clin Exper Allergy. 1999;29(Suppl 3):1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00004.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quach TT, Duchemin AM, Rose C, Schwartz JC. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;60:391–392. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hindmarch I, Shamsi Z. Clin Exper Allergy. 1999;29(Suppl 3):133–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.0290s3133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timmerman H. In: Analogue-based Drug Discovery. Fischer J, Ganellin CR, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. pp. 401–418. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanai K, Okamura N, Tagawa M, Itoh M, Watanabe T. Clin Exper Allergy. 1999;29(Suppl 3):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathews M, Muzina DJ. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:597–606. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.8.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E. Psychopharmacol. 1994;114:559–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02244985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schinkel AH, Jonker JW. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:3–29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benet LZ. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2010 doi: 10.1021/mp900253n. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benet LZ, Wu CY, Hebert MF, Wacher VJ. J Controlled Release. 1996;39:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard GD, Fojo T, Bates SE. Oncologist. 2003;8:411–424. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-5-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada M. Cancer Lett. 2006;234:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chishty M, Reichelt A, Siva J, Abbott NJ, Begley DJ. J Drug Targeting. 2001;9:223–228. doi: 10.3109/10611860108997930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansch C, Björkroth JP, Leo A. J Pharm Sci. 1987;79:663–687. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600760902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leo A. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1281–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ter Laak AM, Tsai RS, Donné-op den Kelder GM, Carrupt P-A, Testa B, Timmerman H. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1994;2:373–384. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C, Hanson H, Watson JW. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(3):312–318. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anonymous. Clin Exper Allergy. 1999;29(Suppl 3):37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timmerman H. personal communication. 2007.

- 29.The following resources were used to annotate “sedation” and “orthostatic hypotension”: Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons, http://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/clarke/current/; DailyMed, http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about.cfm; Drugs@FDA, http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/; European Medicines Agency, http://www.emea.europa.eu/htms/human/epar/a.htm; Martindale http://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/current/; Medicines UK, http://www.medicines.org.uk/; and the Swedish Pharmacopeia (FASS; in Swedish), http://www.fass.se/LIF/home/index.jsp. Note: to access Clarke’s and Martindale, a subscription license is required.

- 30.Olah M, Rad R, Ostopovici L, Bora A, Hadaruga N, Hadaruga D, Moldovan R, Fulias A, Mracec M, Oprea TI. In: Chemical Biology: From Small Molecules to Systems Biology and Drug Design. Schreiber SL, Kapoor TM, Wess G, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2007. pp. 760–786. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The following resources were used to annotate target bioactivity: IUPHAR-DB, http://www.iuphar-db.org/; PDSP, http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/pdsp.php; GPCR-DB, http://www.gpcr.org/7tm/data/.

- 32.Leysen JE, Gommeren W, Eens A, de Chafoy de Courcelles D, Stoof JC, Janssen PAJ. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247:661–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leysen JE, Janssen PMF, Schotte A, Luyten WHML, Megens AAHP. Psychopharmacol. 1993;112:S40–S54. doi: 10.1007/BF02245006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dewan MJ, Koss M. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:229–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sánchez C, Hyttel J. Cell Mol Beurobiol. 1999;19:467–489. doi: 10.1023/A:1006986824213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leurs R, Church MK, Taglialatela M. Clin Exp All. 2002;32:489–498. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillard M, Christophe B, Wels B, Peck M, Massingham R, Chatelain P. Inflamm Res. 2003;52(Suppl 1):S49–S50. doi: 10.1007/s000110300050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harmar AJ, Hills RA, Rosser EM, Jones M, Buneman OP, Dunbar DR, Greenhill SD, Hale VA, Sharman JL, Bonner TI, Catterall WA, Davenport AP, Delagrange P, Dollery CT, Foord SM, Gutman GA, Laudet V, Neubig RR, Ohlstein EH, Olsen RW, Peters J, Pin J-P, Ruffolo RR, Searls DB, Wright MW, Spedding M. Nucl Acids Res. 2009;37:D680–D685. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitebread S, Hamon J, Bojanic D, Urban L. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1421–1433. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popper K. Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge and Keagan Paul; London: 1963. pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, Mol CAAM, van Deemter L. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2517–2524. doi: 10.1172/JCI118699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neuhaus W, Noe CR. In: Transporters as Drug Carriers. Ecker G, Chiba P, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2009. pp. 263–298. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begley DJ. In: Efflux Transporters and the Blood-Brain Barrier. Taylor EM, editor. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2005. pp. 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polli JW, Wring SA, Humphreys JE, Huang JE, Morgan JB, Webster LO, Serabjit-Singh CJ. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:620–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahar Doan KM, Humphreys JE, Webster LO, Wring SA, Shampine LG, Serabjit-Singh CJ, Adkinson KK, Polli JW. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:1029–1037. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varma MVS, Sateesh K, Panchagnula R. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2005;2:12–21. doi: 10.1021/mp0499196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng B, Mills JB, Davidson RE, Mireles RJ, Janiszewski JS, Troutman MD, de Morais SM. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:268–275. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.017434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matthews EJ, Kruhlak NL, Benz RD, Contrera JF. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2004;1:61–76. doi: 10.2174/1570163043484789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Summerfield SG, Stevens AJ, Cutler L, Osuna MC, Hammond B, Tang SP, Hersey A, Spalding DJ, Jeffrey P. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1282–1290. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brøsen K, Klysner R, Gram LF, Otton SV, Bech P, Bertilsson L. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;30:679–684. doi: 10.1007/BF00608215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The FDA label for Xyzal® (levocetirizine) is available online from the National Library of Medicine, http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=7522

- 53.Boyer S. personal communication. 2009.

- 54.Cases M, Mestres J. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crivori P. In: Antitargets. Vaz R, Klabunde T, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. pp. 367–397. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadeque AJ, Wendel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:231–237. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.109156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.