Abstract

From a pure motor disorder of the bowel, in the past few years, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has become a multifactorial disease that implies visceral hypersensitivity, alterations at the level of nervous and humoral communications between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system, alteration of the gut microflora, an increased intestinal permeability and minimum intestinal inflammation. Psychological and social factors can interfere with the communication between the central and enteric nervous systems, and there is proof that they are involved in the onset of IBS and influence the response to treatment and outcome. There is evidence that abuse history and stressful life events are involved in the onset of functional gastrointestinal disorders. In order to explain clustering of IBS in families, genetic factors and social learning mechanisms have been proposed. The psychological features, such as anxiety, depression as well as the comorbid psychiatric disorders, health beliefs and coping of patients with IBS are discussed in relation to the symptoms and outcome.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depressive symptoms, Irritable bowel syndrome, Personality, Psychosocial factors, Sexual abuse, Stressful events

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a frequent diagnosis in clinical practice for gastroenterologists and primary care physicians. It is a burden to society through total direct costs, reduced social functioning and quality of life impairment. IBS has a multifactorial etiology, involving altered gut reactivity and motility, altered pain perception, and alteration of the brain-gut axis. In addition, psychological and social factors can influence digestive function, symptom perception, illness behavior and outcome[1]. Psychological distress and major life events are frequently present in IBS, and are responsible, at least in part, for some outcomes. Whether they are also risk factors for IBS, is still uncertain. Since the biopsychosocial model of IBS was developed[2,3] the number of papers on IBS has skyrocketed. Accordingly, there has been a constant growing interest on the influences of psychosocial factors on the pathogenesis, course, severity and outcome in IBS. This review will highlight the place of environmental and psychosocial stressors in the biopsychosocial model of IBS, and their role in the onset and course of symptoms.

BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL OF IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

The idea that emotions may influence the sensorimotor function of the gastrointestinal tract emerged at the beginning of the 19th century, and a lot of the evidence from research during that period is still valid[4]. Nevertheless, the vivid part of the history of IBS began only three decades ago, when the concept of the biopsychosocial model of illness and disease was developed[5]. This model integrates all possible accountable factors for the pathogenesis and clinical expression in IBS. The biopsychosocial approach allows for symptoms to be both determined and modified by psychological and social influences[3]. The link between psychosocial factors and gastrointestinal function (motility, sensation, inflammation) is through the brain-gut axis. This implies a bidirectional connection system between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain, through neural, neuroimmune and neuroendocrine pathways[6].

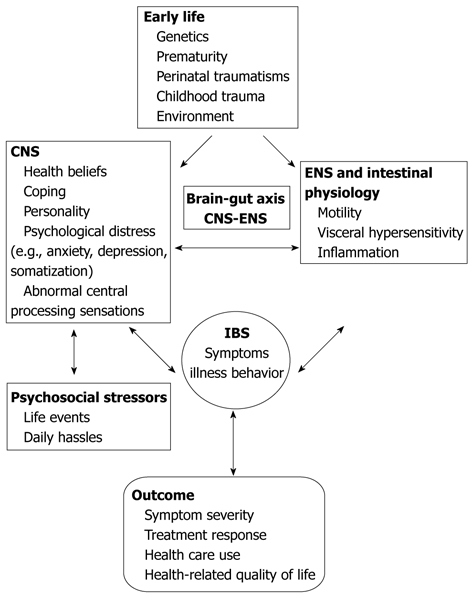

Psychosocial factors influence every component of the biopsychosocial model (Figure 1). Early in life, genetics and environmental factors (e.g., family influences, abuse, major losses), may affect one’s psychosocial development (psychological state, coping skills) and/or the development of gut dysfunction. Gut dysfunction and dysregulation of the brain-gut axis can lead to IBS. During life, psychosocial factors (stressful life events, psychological distress), may influence digestive function, symptom perception, illness behavior, and consequently health outcome, daily function and quality of life[3]. Conversely, visceral pain can affect central pain perception, mood and behavior[7]. The psychological and social factors which may influence IBS are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome: Pathogenesis and clinical expression in relation to psychosocial factors. CNS: Central nervous system; ENS: Enteric nervous system; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome.

Table 1.

Psychological and social factors in irritable bowel syndrome

| Environmental factors |

| Early life events |

| Upbringing environment |

| Incentives |

| Family function |

| Abuse history |

| Psychosocial stressors |

| Life events (divorce, unemployment, death of a close relative) |

| Daily hassles |

| Personality traits |

| Neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness |

| Alexithymia |

| Health beliefs |

| Hypochondriacal beliefs |

| Illness representation |

| Perceived susceptibility |

| Coping strategies |

| Maladaptive coping (catastrophyzing, self-blame, substance abuse) |

| Negative emotions and psychiatric disorders |

| Mood disorders (major depression and dysthymic disorder) |

| Anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder) |

| Somatization and somatoform disorders |

| Neurasthenia |

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES IN IBS

Patients with IBS frequently report a positive family history of IBS, ranging from 33%[8] to 42%[9]. A constant research question is whether the clustering of IBS in families is due to common environmental risk factors or due to a common IBS specific set of genes.

Familial aggregation of IBS and twin studies showed that the concordance for IBS in monozygotic twins is significantly higher than in dizygotic twins, supporting the role of genetics in the etiology of IBS[10]. In the last decade, a lot of genetic studies looked for associations between gene functions (such as IL-10, the serotonin transporter, α-2 adrenergic receptors, and G protein) and gastrointestinal and colonic physiology in IBS patients, and searched for interactions between genotype and phenotypes[11]. So far, a definitive disease-causing gene or set of genes for IBS hasnot been identified.

There is a higher prevalence of IBS among subjects who have a family member with a history of abdominal pain, bowel dysfunction[12] or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[13]. An interesting fact is that subjects whose spouses had abdominal complaints did not report IBS symptoms more often than controls[12]. Only 5.4% of IBD patients’ spouses reported IBS symptoms, vs 10.8% of first degree relatives of IBD patients. Even if these observations support the idea that the inherited pathophysiological mechanisms are more important in IBS clustering in families, the effects of the common environment cannot be excluded.

Prenatal traumatic events may contribute to the development of IBS[14]. For example, exposure to severe wartime conditions in early life (in the first two years of life) was associated with an increased risk of developing IBS. To what extent this is attributable to the stressful environment of war, to severe undernutrition, or to the increased prevalence of infectious diseases is, however, unclear[15]. A large Norwegian population-based twin study[10] (on 12 700 twins) assessed the influence of nutrition in fetal life on the development of IBS, using birth weight as an indicator. The twins with a birth weight below 1500 g were significantly more likely to develop IBS. In addition, weight below 1500 g influenced the age at onset: IBSappeared 7.7 years earlier than in higher weight groups.

A recent study on children who had pyloric stenosis suggested that early stressful life events, such as gastric surgery, and perioperative nasogastric tube placement represent risk factors in the development of chronic abdominal pain in children at long-term follow-up[16].

The role of environmental factors in IBS was studied in a pediatric population in China. Adolescents and children who lived in a single-parent household, children exposed to low temperature environmental conditions, had a higher prevalence of IBS. Dietary habits (such as excessive intake of pepper and cold food) and personal habits (like alcohol consumption and smoking) were also associated with higher rates of IBS symptoms among children and adolescents[17]. On the other hand, two studies reported that an affluent childhood social class was associated with an increased risk of IBS[18,19]. One study concluded that privileged childhood living conditions (childhood living density < 1 person per room) was an important risk factor for IBS[18]. Howell et al[19] showed that there is a linear decrease in the odds of IBS across decreasing levels of social class.

Data regarding the effects of family environment are scarce. One study reported that by the age of 15 years, in 333 IBS patients, 31% had lost a parent through death, divorce or separation; 19% had an alcoholic parent, and 61% reported unsatisfactory relationships with, or between their parents[20]. Therefore, childhood deprivation may have an important influence on the etiology of IBS.

The clustering of IBS in families could partially be the result of social learning during childhood. The children of mothers with IBS have more non-gastrointestinal (GI) as well as GI symptoms (especially stomach aches), more school absences, and more physician visits for GI symptoms than children of non-IBS mothers[21]. In addition, children whose mothers made solicitous responses to illness complaints reported more severe stomach aches and they also had more school absences for stomach aches. Thus, children may learn abnormal illness behavior from their parents through social learning from parental reactions to symptom complaints[14].

ABUSE HISTORY

The role of abuse (especially childhood abuse) in IBS patients is still unclear. So far, authors have tried to determine (1) whether abuse is a risk factor for IBS; (2) whether there is a higher prevalence of abuse among IBS patients compared with other gastrointestinal diseases or healthy controls; (3) the effects of abuse on clinical outcome; and (4) the relationship between abuse and psychological distress, as a possible explanation of abuse-IBS association.

The prevalence of abuse history among patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) varies widely. When comparing different data, we should consider at least three aspects: cultural differences which can lead to lower or higher self-report rates; the measurement methods of abuse used in different studies; and the type of abuse considered: physical, emotional/verbal or sexual. Also, the type of sexual act that is considered abusive varies from exhibitionism, fondling or contact abuse, to penetration or rape[22]. Given these facts, the prevalence of sexual and emotional abuse in IBS varies from 26%[23] to 50.8%[24], but lower values have also been reported. In other studies only 17% of abused patients had reported the abuse[25], therefore, the actual prevalence of abuse is usually higher.

In our experience, of 125 female patients with IBS, only one admitted she had “an undesired sexual contact”, leading to a less than 1% reported frequency of sexual abuse. On the other hand, of 15 abused children from a specialized care center, seven met Rome III criteria for IBS. We consider that the cultural differences between Romania and Western European countries are responsible for this under-recognition of abuse in female IBS patients[26].

There are studies which show that the prevalence of abuse history in patients with functional bowel disorders is greater than that in patients with organic bowel disorders and healthy control subjects[25,27,28]. Other studies failed to reinforce this observation[29]. Nevertheless, a constant finding is that abused individuals express higher levels of psychological distress[28,29] and higher levels of somatization[25,30], suggesting that previous abuse experience might lead to psychiatric disorders. There are significant data showing that anxiety disorders, depression[31] and somatization[32], are risk factors for IBS.

Two recent studies concluded that a lifetime history of a broad range of trauma and abuse, either in childhood or in adult life are independently associated with an increased IBS risk[30,33]. In a study that included women veterans[33], who are at increased risk of occupational trauma, including sexual trauma, the prevalence of IBS was 33.5%, and the most frequently reported trauma was sexual assault (38.9%). Even when depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were significantly more common in IBS cases than controls, neither explained the association between trauma and increased IBS risk.

Even if the role of abuse in IBS remains unclear, it was proven that abuse leads to increased psychological distress. Most probably, as a consequence, abuse is associated with greater impairment of functioning in daily lives, more visits to the doctor[25] and a poorer health outcome[34].

There are more and more data supporting the inherited component of IBS, but at the same time, the influences of the upbringing environment cannot be disregarded. IBS remains a multifactorial, complex disorder, caused by both environmental (Table 2) and genetic risk factors[9,11].

Table 2.

Environmental factors associated with irritable bowel syndrome

| Prenatal traumatic events (e.g., nutrition in fetal life) |

| Early stressful life events (surgery, emotional, physical or sexual abuse) |

| Upbringing environment (low temperature, affluent childhood social class) |

| Family function (divorce, death of a parent) |

| Family history of abdominal pain, bowel dysfunction, inflammatory bowel diseases |

| Social learning (modeling) |

| Abuse history either in childhood or during adult life |

PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESSORS

Lazarus[35] divided stressors into life events and daily hassles. Life events refer to major events such as divorce, unemployment, or death of a close relative. Daily hassles are events which everybody experiences daily and frequently[36]. His assumption is that “(daily) hassles appear to be better predictors of health outcomes than life events”. The results of a recent prospective study support this theory: there was a significant increase in stressor score (daily hassles) just before progression from IBS non-patient to IBS patient[37]. The majority of the subjects in this study however, were young college students, so factors rated as relatively stressful life events, were not very common.

The current data regarding the role of life events in the onset of IBS are the result of observations from the 80s. For example, Creed et al[38] showed that the most frequent events reported by patients with functional abdominal pain (FAP) (including IBS patients) during 38 wk prior to onset of symptoms, were a major disruption of close relationships, a marital separation, a family member leaving home, or break-up of a serious girl/boyfriend relationship. In addition, marked personal relationship difficulties such as severe marital problems or extreme family or household tensions, were much more frequently recorded among the FAP patients than in the organic GI diseases group (such as ulcer disease) or community subjects.

Recent data support the role of major life events in IBS. Childhood trauma was associated with an increased vulnerability for multiple somatic symptoms of which IBS is one subset[30]. The items reported significantly more frequently in IBS than in healthy controls were: seeing someone being murdered, death or illness of a parent, failing to be understood by parents and having someone in the family with a psychiatric illness.

Holocaust survivors are another example of the impact of stressful life events on the development of IBS. The prevalence of IBS, duration of suffering, and frequency of GI symptoms were significantly higher in Holocaust survivors[39], when compared to controls with the same demographic background, but who had not been exposed to extreme mental and physical hardships during the war. From our personal experience[40], the stress developed by dramatic events presented live on television, during the uprising in Romania in 1989, led to an increased number of IBS symptoms within the first month.

Sometimes, what is considered to be a major life event is difficult to determine. For instance, a sudden cultural change (such as moving from a rural to an urban area) increased the prevalence of IBS in one study[41].

The experience of stressful life events can also determine symptom exacerbation among adults with IBS and frequent health-care seeking[7,42]. Thus, the severity of abdominal pain was higher in patients exposed to emotional stress[43], and stress exacerbated abdominal distension in one third of IBS patients[44]. In addition, recent data showed that environmental factors and psychosocial stressors (for example history of being psychologically abused, less than 6 h of sleep and irregular diet) influenced the progression from an IBS non-consulter to an IBS patient[37].

Based on these data we can say that psychosocial stressors, either during childhood or later in life are involved in the onset of IBS symptoms in susceptible individuals, and these factors influence the clinical course of IBS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Psychosocial stressors and their relation to irritable bowel syndrome

| Daily hassles, major life events (divorce, unemployment, or death of a close relative), and major social events (surviving holocaust, revolution, social changes) determine the onset of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms in susceptible individuals |

| Psychosocial stressors determine symptom exacerbation and health care seeking |

PERSONALITY TRAITS

Personality is also considered to play a role in the etiology of IBS and in the decision to seek medical help. Personality traits have been defined as a “dynamic organization, inside the person (…) that create a person’s characteristic patterns of behavior, thoughts and feelings”[45]. There are still debates regarding the major determinants of personality, and which personality traits should be included in psychometric questionnaires. However, very often, personality is assessed based on five dimensions: extraversion (talkativeness, assertiveness, activity vs silence, passivity and reserve); agreeableness (kindness, trust, and warmth vs selfishness and distrust); conscientiousness (organization, thoroughness, and reliability vs carelessness, negligence and unreliability); neuroticism (tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression; also called emotional instability); and openness to experience (imagination, curiosity, and creativity vs shallowness and imperceptiveness)[46,47].

The majority of studies on this topic supports the idea that IBS patients have higher levels of neuroticism both when compared with the general population[48], and with patients with similar GI complaints (IBD patients)[49]. Neuroticism might influence coping strategies, being associated with escaping the problem or blaming oneself[50]. Neuroticism is also a significant predictor of illness perception and treatment beliefs in IBS[49].

Data are sometimes discordant with regard to the other dimensions of personality. The level of conscientiousness in IBS patients was high in some studies[48], while only average when compared with FD in other studies[51]. The differences may come from the fact that in some studies patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders were excluded[48].

Alexithymia is a stable personality trait, which is also frequently observed in IBS patients. Alexithymia is defined as a difficulty in identifying feelings and distinguishing between feelings and bodily sensations, difficulty describing feelings to other people, a markedly constricted imaginative process, and externally oriented thinking[52,53]. The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20)[54] is the most widely used questionnaire to measure a person’s alexithymia level. Subjects with a TAS-20 score > 61 (the score ranges from 20 to 100) are considered alexithymic. In the general population, less than 10% of patients are alexithymic[55]. In an Italian study, IBS patients had higher TAS-20 scores than healthy controls (59.1 vs 40.5). In addition, 43% of IBS patients had a TAS-20 score > 61, while only 2% of healthy subjects were alexithymic[56]. Our personal data on a female IBS population showed similar results[57]. Alexithymic individuals may misinterpret the somatic sensations associated with emotional arousal as symptoms of disease. It follows that, alexithymia is often associated with somatization, also a frequent finding in IBS patients[58]. Table 4 summarizes the association between personality traits and IBS.

Table 4.

Personality traits and irritable bowel syndrome

| Neuroticism and alexithymia are common in irritable bowel syndrome patients |

| Neuroticism is a predictor of illness perception and influences coping strategies |

| Examples of measurement tools: Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Inventory[46] |

HEALTH BELIEFS AND COPING WITH STRESS

A lot of patients with IBS believe that their chronic gut symptoms indicate a serious illness or even cancer. In addition, patients describe IBS not only as symptoms but mainly as it affects daily function, thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Patients report the sense of losing freedom, spontaneity and social contacts, as well as feelings of fearfulness, shame, and embarrassment. All these could lead to changes in their behavior such as avoidance of activities and many adaptations in routine in an effort for patients to gain control[59].

The most extreme form of preoccupation with an illness is hypochondriasis, included in the group of somatoform disorders. Hypochondriasis is the excessive fear of a serious illness, despite medical testing and reassurance to the contrary[60]. In a study from the 90s, patients with IBS expressed more hypochondriacal attitudes when compared with healthy subjects or patients with organic GI diseases. Patients with IBS had high scores on bodily preoccupation, hypochondriacal beliefs and disease phobia[61]. No other data on this subject are available. We cannot recommend screening for hypochondriacal attitudes, but in everyday practice, we can encounter IBS patients with excessive illness-related fear. The presence of hypochondriacal attitudes can be measured using the Illness Attitudes Scales (IAS) questionnaire. This questionnaire was developed in 1986[62], but even now remains a valid tool[63].

Psychological assessment of IBS patients revealed that there are differences regarding how individuals with IBS respond to their illness. In other words, IBS patients do adopt different coping strategies compared with patients with organic diseases or healthy controls. Coping is defined as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person”[36]. The authors divided coping strategies into two main categories: problem-focused coping targeting directly the causes of stress, such as information seeking, constructive way of reducing/solving the problem and planning, and emotion-focused coping used to handle negative emotions evoked by the situation (such as an avoiding feeling, trying to escape the problem or blaming oneself).

There are a number of questionnaires which assess coping strategies, such as the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)[64], Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ)[65] and Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation (CISS)[66]. All of these include the main coping strategies mentioned. The CISS has proved so far to have very good psychometric properties and was validated in several languages[67].

Using WCQ, Drossman et al[50] showed that patients with IBS and other FGIDs, didnot use positive reappraisal as often as patients with organic disorders (such as IBD, acid peptic disease, pancreatico-biliary diseases). In a polish study, IBS patients had a high emotional-oriented coping style[51].

The CSQ focuses primarily on coping in response to painful conditions. The interest in using the CSQ in patients with IBS is related to the subscale measuring catastrophyzing (e.g., “When I am in pain, I feel I can’t stand it anymore” or “it’s awful and I feel it overwhelms me”). Catastrophyzing is a maladaptive coping strategy defined as “a negative cognitive process of exaggerated negative rumination and worry”[68]. Patients with IBS are more likely to catastrophize than patients with organic disorders[50]. In addition, catastrophyzing mediates the relationship between depression and pain severity. This relationship was suggested by the following observations: patients with IBS and a high degree of catastrophyzing have a tendency to report more severe pain; catastrophyzing and depression are associated[69]; depression did not predict symptom severity[70]. Patients with IBS who experience higher levels of depression engage in more catastrophic thinking, and partly through this thinking style experience more intense pain and greater activity limitations due to pain[69].

The CSQ also measures the overall effectiveness of coping strategies (the amount of control over symptoms and self-perceived ability to decrease symptoms). IBS patients were less likely to feel in control of symptoms and to feel able to decrease symptoms than patients with organic disorders[50], suggesting that coping strategies are not very efficient in IBS patients.

When speaking about coping styles in IBS patients it is difficult to draw a general conclusion. The studies mentioned above used different questionnaires to assess coping strategies in IBS. The results are not contradictory, but at the same time didnot point out a specific coping strategy in IBS patients (see also the summary in Table 5). Further research is necessary to establish the role of coping in symptom perception and control, and clinical outcome in IBS patients.

Table 5.

Health beliefs and coping with stress in relation to irritable bowel syndrome

| Health beliefs in IBS may be irrational, leading to hypochondriacal attitudes |

| Coping strategies can be inefficient in IBS patients, patients often adopt maladaptive coping strategies such as catastrophyzing |

| Patients with a high degree of catastrophyzing report more severe pain |

| Measurement methods: CSQ, CISS, WCQ |

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; CSQ: Coping strategies questionnaire; CISS: Coping inventory for stressful situation; WCQ: Ways of coping questionnaire.

NEGATIVE EMOTIONS AND COMORBID PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSIS

Psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric disorders are more common in patients seen in referral practices than primary care or in the community of nonconsulters. The most frequent psychiatric diagnosis in IBS is mood disorders (major depression and dysthymic disorder), anxiety disorders and somatoform disorders[7].

Depression is the most common psychiatric diagnosis in IBS patients[71,72]. Patients with IBS have higher scores of depression than healthy controls[73,74], but lower than the psychiatric population[7,73]. However, depressive disorders are more common in clinic patients with IBS compared to patients with similar symptoms and organic GI diseases and compared to healthy controls[72,75]. In the study by Whitehead et al[72], the prevalence of depression in IBS was 31.4%, 21.4% in IBD and 17.5% in controls. Another study reported a lower prevalence of depression in IBS than in patients with chronic C hepatitis[76]. An interesting fact is that the number of self-reported depressive symptoms is not significantly higher in patients who seek medical care for their GI complaints compared with those who do not consult[75].

Anxiety and anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are also often observed in IBS patients. Anxiety tends to precede IBS onset, particularly if diarrhea predominates. This indicates that the psychiatric disorder cannot be regarded as a response to the functional GI disorder. It seems more likely that the psychiatric symptoms, especially anxiety, play a role in the development of IBS[31].

Anxiety is more common in IBS patients than in the general population[77,74]. In a community study, GAD was found in 16.5% of subjects with IBS symptoms, while in the group of subjects without these symptoms the prevalence was 3.3%[77]. Whitehead et al[72]reported similar results (15.8%) regarding the frequency of anxiety among IBS patients. However, other studies reported higher values. For example, 47% of patients with IBS met Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) screening criteria for anxiety in a South Australian study[76].

This significant difference in prevalence may have at least two causes. The first one refers to the sample of subjects taken into account-some studies were conducted on samples of patients seeking medical care, mostly in tertiary care settings; other studies investigated community subjects. The second explanation may be that the authors used different scales or criteria to establish the presence of anxiety. Lee et al[77] used the diagnosis criteria for GAD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders[60]. HADS is a widely used instrument developed as a screening tool for detecting states of depression and anxiety in hospital settings[78]. Studies have also shown that HADS is valid when used in community settings and primary care medical practice[79]. HADS should be used only to estimate the likely prevalence of anxiety and depression, and not to establish a firm diagnosis. The latter can only be made by a psychologist or a psychiatrist using a structured interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV.

Anxiety related to GI sensations, symptoms or the context in which these may occur is referred to as gastrointestinal specific anxiety (GSA). GSA influences symptom severity and quality of life in patients with IBS[80]. Patients with IBS have more severe GSA when compared with healthy subjects. In addition, IBS patients with severe GI symptoms have more severe GSA scores[81]. GSA can be assessed using The Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI), a 15-item scale developed for this purpose[80]. The main information from measuring GSA, is related to the fact that the GSA score predicts GI symptom severity[81].

Data regarding the frequency of PD in IBS are scarce. Panic disorder is characterized by repeated, unexpected panic attacks, and is more common in women. Sufferers experience unexpected episodes of intense fear and associated cardiorespiratory, GI, neurological, and cognitive symptoms[60]. A study conducted in several secondary and tertiary gastroenterology clinics, reported that 12% of IBS patients had PD, 14% had GAD and 29% had depressive disorder[71]. The frequency of GAD and depressive disorder are similar to those mentioned above, even if the criteria used for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders were different. Studies in female veterans, showed that IBS is more common in patients with PTSD, and PTSD represents an independent risk factor for IBS[33,82].

Somatization disorder (SD) is included, according to DSM-IV, in the larger group of somatoform disorders. SD is defined as a chronic condition in which “the individual experiences physical symptoms that suggest the presence of a general medical condition, but a medical workup cannot establish an etiological general medical condition that adequately explains the problem”[60]. Several studies conducted on tertiary care IBS patients reported an excessive somatization tendency in patients with IBS, the prevalence of SD reaching 25%[83,84]. However, a review on SD, mentioned that in primary care and in population-based samples, SD is very rare, with a lifetime prevalence of only 0.1% to 0.2%[85].

High scores on somatization questionnaires in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) were observed both in population-based studies and in clinical studies[86]. Somatization is frequently associated with anxiety and depression, and explains the frequent “extragastrointestinal symptoms” such as musculoskeletal complaints, urinary symptoms, sexual symptoms, headaches, and constant fatigue observed in patients with IBS[84,87]. It is also associated with a poor health-related quality of life, and predicts a poor response to treatment[88-90].

Recent data endorse these assumptions and also suggest that somatization is a risk factor for IBS. In a study conducted in a tertiary care setting on functional dyspepsia patients, somatization was found to be a common risk factor for co-morbid IBS and chronic fatigue-like symptoms[32]. A community-based prospective study[91], showed that psychosocial factors indicative of somatization (such as illness behavior scores, anxiety, sleep problems and somatic symptoms) are independent risk markers for the development of IBS, in a group of subjects previously free of IBS. After one year follow-up, 3.5% of the followed subjects developed IBS. Those who reported all four of these markers at baseline were six times more likely to report IBS when compared to those who were exposed to none or one marker.

Those who have SD use health services frequently, and have twice the annual medical care cost of people without SD[92]. This finding is also true for IBS patients, as patients with IBS and SD have a significantly greater number of medical consultations, telephone calls to physicians, urgent care visits, medication changes, missed work days and benzodiazepine use[84]. In addition, IBS patients with probable or definite somatization report more abnormal illness behaviors than those without SD[83].

Neurasthenia is also frequently reported in IBS patients, up to 35% in severe IBS patients[71]. It is very similar to chronic fatigue syndrome, being characterized by persistent and distressing fatigue after mental or physical effort associated with muscular aches, dizziness, sleep disturbance, irritability and mild depressive symptoms[60,93]. This entity is currently contested by some authors[93]. It is still included in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, but not in DSM-IV, due to its overlap with anxiety and depression.

Patients with IBS very often have more than one psychiatric disorder, and this finding is more common in severe IBS. For example in 74 patients with depressive disorder and severe IBS[71], 16 had PD, 6 had hypochondriasis and 41 had neurasthenia. Other psychiatric diagnoses reported in this study were dysthymia (7%), phobias (15%), undifferentiated somatoform disorder (9%) and drug or alcohol problems (8%).

Psychological distress is seen more often in IBS patients than in the general population. It also holds true that in patients with psychiatric disorders, IBS symptoms are more frequently reported than in the general population. In a community study, IBS was 4.7 times more common among patients with GAD than in the general population (22% vs 4.7%)[77]. Frequent abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, dyspepsia or IBS were present in 54% of subjects with depressive symptoms and in only 29% of non-depressed controls[86]. Patients with PD also have high rates of IBS symptoms[94-96], varying from 26.3%[96] to 46.3%[94], most probably due to different diagnostic criteria for IBS.

Numerous instruments have been developed to assess the presence of psychiatric symptoms or specific psychiatric disorders in IBS patients. The complexity of these questionnaires is clearly related to the purpose, which can either be screening or diagnosis, or research. One can obtain a general idea about a patient’s psychological distress in IBS using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), developed by Derogatis[97]. The SCL-90-R has 9 subscales, including subscales for somatization, depression and anxiety, and provides an overview of symptom intensity at a specific point in time. From the three global indices determined, the Global Severity Index (GSI) measures overall psychological distress. The State-trait anxiety inventory[98] (STAI) and the Beck depression inventory[99] are another two questionnaires commonly used to assess the presence of anxiety and depression in IBS patients.

In the general population, half of patients with presumed IBS have psychiatric symptoms compared with one third in controls[100]. In several systematic reviews published at the beginning of the 2000’s, the proportion of patients who met the criteria for any psychiatric diagnosis ranged from 40% to 94%[42,101,102]. We should take into account that some data are the results of studies conducted on tertiary care patients who are likely to be more distressed than other patients. Some studies did not evaluate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in other chronic GI diseases, in the same setting. In addition, the criteria used to diagnose psychiatric disorders differed from one study to another. In a study by Creed et al[103] in severe IBS patients, 42% of patients had a concurrent psychiatric disorder (depressive, panic or generalized anxiety disorder). Even if this study didnot purposely determine the frequency of psychiatric disorders in IBS patients, it showed that even in the most severe IBS patients, a comorbid psychiatric disorder is found in less than half of the patients. In summary (Table 6), half or more IBS patients commonly have psychiatric symptoms or psychiatric disorders and their frequency is higher than for other medical patients in the same clinics.

Table 6.

Comorbid psychiatric diagnoses and their relation to irritable bowel syndrome

| Psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric diseases are frequent in IBS, especially in severe forms |

| Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder in IBS (approximately 30% of patients) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder is present in about 15% of patients |

| High gastrointestinal specific anxiety predicts symptom severity |

| High levels of somatization determine frequent use of health care services, a poor response to treatment and a poor health-related quality of life |

| Other psychiatric disorders in IBS patients: posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, dysthymia, phobias, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, drug or alcohol problems |

| Patients with severe IBS may have more than one psychiatric disorder |

| Measurement methods: Symptom checklist-90-revised for overall psychological distress; state-trait anxiety inventory, beck depression Inventory |

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome.

CONCLUSION

Environmental and psychosocial factors are an important part of the biopsychosocial model of IBS, being involved in dysregulation of the brain-gut axis, leading to the onset of IBS, persistence of symptoms or abnormal illness behavior. There is a wide range of environmental and psychosocial stressors, acting at different moments in one’s life; a number of people submit to these factors, but only susceptible individuals will develop IBS. Other major elements of the biopsychosocial model such as personality traits and psychiatric disorders are probably the elements which make one susceptible to the development of IBS.

Footnotes

Supported by The Sectorial Operational Programme Human Resources Development, Contract POSDRU 6/1.5/S/3-, Doctoral studies: through science towards society

Peer reviewer: Justin C Wu, Professor, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 9/F, Clinical Science Building, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional Bowel Disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ, et al., editors. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc; 2006. pp. 487–555. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA. Presidential address: Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258–267. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller R, Talley NJ, et al., editors. Rome III: the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc; 2006. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Demyttenaere K, Tack J. Psychosocial factors, psychiatric illness and functional gastrointestinal disorders: a historical perspective. Digestion. 2010;82:201–210. doi: 10.1159/000269822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones MP, Dilley JB, Drossman D, Crowell MD. Brain-gut connections in functional GI disorders: anatomic and physiologic relationships. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creed FH, Levy R, Bradley L, Drossman DA, Francisconi C, Naliboff BD andOlden KW. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ, et al., editors. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc; 2006. pp. 295–368. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam B, Liebregts T, Holtmann G. Mechanisms of disease: genetics of functional gastrointestinal disorders--searching the genes that matter. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:102–110. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito YA, Zimmerman JM, Harmsen WS, De Andrade M, Locke GR, Petersen GM, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome aggregates strongly in families: a family-based case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:790–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.1077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bengtson MB, Rønning T, Vatn MH, Harris JR. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: genes and environment. Gut. 2006;55:1754–1759. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.097287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camilleri M. Genetics and irritable bowel syndrome: from genomics to intermediate phenotype and pharmacogenetics. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2318–2324. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Familial association in adults with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:907–912. doi: 10.4065/75.9.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguas M, Garrigues V, Bastida G, Nos P, Ortiz V, Ponce J. Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in First-Degree Relatives of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Quality of Life and Economic Impact. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S–627. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–774; quiz 775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klooker TK, Braak B, Painter RC, de Rooij SR, van Elburg RM, van den Wijngaard RM, Roseboom TJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Exposure to severe wartime conditions in early life is associated with an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2250–2256. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saps M, Bonilla S. Early life events: infants with pyloric stenosis have a higher risk of developing chronic abdominal pain in childhood. J Pediatr. 2011;159:551–4.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong L, Dingguo L, Xiaoxing X, Hanming L. An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and children in China: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e393–e396. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendall MA, Kumar D. Antibiotic use, childhood affluence and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:59–62. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell S, Talley NJ, Quine S, Poulton R. The irritable bowel syndrome has origins in the childhood socioeconomic environment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1572–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hislop IG. Childhood deprivation: an antecedent of the irritable bowel syndrome. Med J Aust. 1979;1:372–374. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1979.tb126963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Garner M, Christie D. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2442–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han C, Masand PS, Krulewicz S, Peindl K, Mannelli P, Varia IM, Pae CU, Patkar AA. Childhood abuse and treatment response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a post-hoc analysis of a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine controlled release. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:79–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, Li ZM, Gluck H, Toomey TC, Mitchell CM. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dumitrascu DL, Stanculete M, Costin S, Dumitrascu D, editors. Geographical Differences in the Report of Sexual Abuse in Females with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. 19th World Congress on Psychosomatic Medicine; 2007 August 26-31; Canada. Québec City. Canada. Québec City: Official Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beesley H, Rhodes J, Salmon P. Anger and childhood sexual abuse are independently associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15:389–399. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. A history of abuse in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: the role of other psychosocial variables. Digestion. 2005;72:86–96. doi: 10.1159/000087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbis IC, Turpin G, Read NW. A re-examination of the relationship between abuse experience and functional bowel disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:423–430. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Videlock EJ, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L. The Effect of Childhood Trauma and Abuse on the Development of Irritable Bowel Syndrome is Mediated by Somatization. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S–144. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sykes MA, Blanchard EB, Lackner J, Keefer L, Krasner S. Psychopathology in irritable bowel syndrome: support for a psychophysiological model. J Behav Med. 2003;26:361–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1024209111909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Holvoet L, Tack J. Factors associated with co-morbid irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue-like symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:524–e202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White DL, Savas LS, Daci K, Elserag R, Graham DP, Fitzgerald SJ, Smith SL, Tan G, El-Serag HB. Trauma history and risk of the irritable bowel syndrome in women veterans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:551–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drossman D, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Whitehead WE, Dalton CB, Leserman J, Patrick DL, Bangdiwala SI. Characterization of health related quality of life (HRQOL) for patients with functional bowel disorder (FBD) and its response to treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1442–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazarus RS. Theory-Based Stress Measurement. Psychological Inquiry. 1990;1:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 141–327. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujii Y, Nomura S. A prospective study of the psychobehavioral factors responsible for a change from non-patient irritable bowel syndrome to IBS patient status. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Creed F, Craig T, Farmer R. Functional abdominal pain, psychiatric illness, and life events. Gut. 1988;29:235–242. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stermer E, Bar H, Levy N. Chronic functional gastrointestinal symptoms in Holocaust survivors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:417–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumitrascu DL, Baban A. Irritable bowel syndrome complaints following the uprising of December 1989 in Romania. Med War. 1991;7:100–104. doi: 10.1080/07488009108408973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sperber AD, Friger M, Shvartzman P, Abu-Rabia M, Abu-Rabia R, Abu-Rashid M, Albedour K, Alkranawi O, Eisenberg A, Kazanoviz A, et al. Rates of functional bowel disorders among Israeli Bedouins in rural areas compared with those who moved to permanent towns. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:342–348. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palsson OS, Drossman DA. Psychiatric and psychological dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome and the role of psychological treatments. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:281–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devanarayana NM, Mettananda S, Liyanarachchi C, Nanayakkara N, Mendis N, Perera N, Rajindrajith S. Abdominal pain-predominant functional gastrointestinal diseases in children and adolescents: prevalence, symptomatology, and association with emotional stress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:659–665. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182296033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang L, Lee OY, Naliboff B, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Sensation of bloating and visible abdominal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3341–3347. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Perspective on personality. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R Professional Manual (Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory) Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamorro-Premuzic T. Personality and individual differences. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farnam A, Somi MH, Sarami F, Farhang S. Five personality dimensions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:959–962. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tkalcić M, Hauser G, Stimac D. Differences in the health-related quality of life, affective status, and personality between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:862–867. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283307c75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Keefe F, Hu YJ, Toomey TC. Effects of coping on health outcome among women with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:309–317. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wrzesińska MA, Kocur J. [The assessment of personality traits and coping style level among the patients with functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome] Psychiatr Pol. 2008;42:709–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sifneos PE. Alexithymia: past and present. Am J Psychiat. 1996;153:137–142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor GJ, Taylor HS. Alexithymia. In: McCallum M, Piper WE, et al., editors. Psychological mindedness: A Contemporary Understanding (Personality & Clinical Psychology) Munich: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD. The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:277–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mattila AK, Saarni SI, Salminen JK, Huhtala H, Sintonen H, Joukamaa M. Alexithymia and health-related quality of life in a general population. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:59–68. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Baldassarre G, Altomare DF, Palasciano G. Pan-enteric dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients meeting ROME II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2293–2299. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costin S, Petrar S, Dumitrascu DL. Alexithymia in Romanian females with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) J Psycho Res. 2006;61:426. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattila AK, Kronholm E, Jula A, Salminen JK, Koivisto AM, Mielonen RL, Joukamaa M. Alexithymia and somatization in general population. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:716–722. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816ffc39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drossman DA, Chang L, Schneck S, Blackman C, Norton WF, Norton NJ. A focus group assessment of patient perspectives on irritable bowel syndrome and illness severity. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1532–1541. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Widiger TA, Thomas A, editors . Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychatric Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gomborone J, Dewsnap P, Libby G, Farthing M. Abnormal illness attitudes in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:227–230. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00126-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kellner R. Somatization and hypochondriasis. New York: Praeger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sirri L, Grandi S, Fava GA. The Illness Attitude Scales. A clinimetric index for assessing hypochondriacal fears and beliefs. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:337–350. doi: 10.1159/000151387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of coping questionnaire manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Endler NS, Parker JDA. Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS): Manual. 2nd ed. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwarzer R, Schwarzer C. A critical survey of coping instruments. In: Zeidner M, EndlerNS , et al., editors. Handbook of coping: theory, research, applications. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. pp. 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keogh E, Asmundson GJG. Negative affectivity, catastrophyzing and anxiety sensitivity. In: Asmundson GJG, Vlaeyen JWS, Crombez G, et al., editors. Understanding and treating fear of pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lackner JM, Quigley BM, Blanchard EB. Depression and abdominal pain in IBS patients: the mediating role of catastrophizing. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:435–441. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126195.82317.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drossman DA. Do psychosocial factors define symptom severity and patient status in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Med. 1999;107:41S–50S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Creed F, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Palmer S, Rigby C, Tomenson B, Guthrie E, Read N, Thompson DG. Outcome in severe irritable bowel syndrome with and without accompanying depressive, panic and neurasthenic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:507–515. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RL, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Turner MJ. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in irritable bowel (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Gastroenterology. 2003;124:A398. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Savas LS, White DL, Wieman M, Daci K, Fitzgerald S, Laday Smith S, Tan G, Graham DP, Cully JA, El-Serag HB. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia among women veterans: prevalence and association with psychological distress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graham DP, Savas L, White D, El-Serag R, Laday-Smith S, Tan G, El-Serag HB. Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms and health related quality of life in female veterans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Andrews JM, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Harley HA, Hetzel DJ, Holtmann GJ. Psychological problems in gastroenterology outpatients: A South Australian experience. Psychological co-morbidity in IBD, IBS and hepatitis C. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee S, Wu J, Ma YL, Tsang A, Guo WJ, Sung J. Irritable bowel syndrome is strongly associated with generalized anxiety disorder: a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:643–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sarna T, Mailer C, Hyde JS, Swartz HM, Hoffman BM. Electron-nuclear double resonance in melanins. Biophys J. 1976;16:1165–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85765-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, Wiklund I, Naesdal J, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. The Visceral Sensitivity Index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jerndal P, Ringström G, Agerforz P, Karpefors M, Akkermans LM, Bayati A, Simrén M. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: an important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:646–e179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, Bush KR, Davis TM, Bradley KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:394–400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller AR, North CS, Clouse RE, Wetzel RD, Spitznagel EL, Alpers DH. The association of irritable bowel syndrome and somatization disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13:25–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1009060731057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.North CS, Downs D, Clouse RE, Alrakawi A, Dokucu ME, Cox J, Spitznagel EL, Alpers DH. The presentation of irritable bowel syndrome in the context of somatization disorder. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:787–795. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Creed F, Barsky A. A systematic review of the epidemiology of somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:391–408. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Locke GR, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zimmerman J. Extraintestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel diseases: nature, severity, and relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:743–749. doi: 10.1023/a:1022840910283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, Lacy BE, Olden KW, Crowell MD. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2454–2459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halder SL, Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: a population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:233–242. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-2813.2004.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holtmann G, Kutscher SU, Haag S, Langkafel M, Heuft G, Neufang-Hueber J, Goebell H, Senf W, Talley NJ. Clinical presentation and personality factors are predictors of the response to treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia; a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:672–679. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000026317.00071.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nicholl BI, Halder SL, Macfarlane GJ, Thompson DG, O’Brien S, Musleh M, McBeth J. Psychosocial risk markers for new onset irritable bowel syndrome--results of a large prospective population-based study. Pain. 2008;137:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:903–910. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee S, Kleinman A. Are somatoform disorders changing with time? The case of neurasthenia in China. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:846–849. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kaplan DS, Masand PS, Gupta S. The relationship of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and panic disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8:81–88. doi: 10.3109/10401239609148805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lydiard RB, Greenwald S, Weissman MM, Johnson J, Drossman DA, Ballenger JC. Panic disorder and gastrointestinal symptoms: findings from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:64–70. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lydiard RB. Increased prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in panic disorder: clinical and theoretical implications. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:899–908. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R, Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual for the Revised Version. 2nd ed. Towson: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hillilä MT, Siivola MT, Färkkilä MA. Comorbidity and use of health-care services among irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:799–806. doi: 10.1080/00365520601113927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B, Read N, Thompson DG. Does psychological treatment help only those patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome who also have a concurrent psychiatric disorder? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:807–815. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]