Abstract

The immune system plays a critical role determining the outcomes in transplanted multiple myeloma patients, since enhanced lymphocyte recovery results in improved survival. Since mobilization regimens influence the cellular subsets collected and infused for transplant, these regimens may determine immune recovery following transplant. We hypothesized that a mobilized stem cell product harboring an increased number of lymphocytes would enhance immune recovery following autologous stem cell infusion, increase lymphocyte recovery, and improve clinical outcomes. We designed a phase I immune mobilization trial using IL-2 and growth factors to increase the number of lymphocytes within the stem cell product. This regimen efficiently mobilized CD34+ progenitor cells (median: 3.6 × 106 cells/kg; range 1.9–6.6 × 106 cells/kg) and improved the immune properties of the mobilized stem cells, including an increase in CD8+ T cells expressing an NK activating receptor called NKG2D (P< 0.004), cells that are extremely potent at killing myeloma cells using non-MHC-I restricted and TCR-independent mechanisms. Novel mobilization techniques can improve the mobilized graft and may improve clinical outcomes in myeloma patients.

Keywords: Myeloma, Effector Cells, Immune Mobilization, Il-2, NKG2D

2. INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable disease with a median survival of 3 to 7 years after diagnosis. (1) Autologous stem cell transplant improves survival but the immunologic mechanisms accounting for this improvement are unknown.

The immune system plays an integral part in the survival of myeloma patients. For example, myeloma patients demonstrating a higher absolute lymphocyte count on day 15 (ALC15) following transplantation experience an improved survival. (2–8) In addition, the number of lymphocytes infused as part of the stem cell product directly impacts the ALC15. (2, 9) The cellular subsets of the stem cell product that are responsible for these benefits are unknown. Therefore, we hypothesized that a mobilized stem cell product containing an increased number of lymphocytes, enriched for tumor-destroying cells, would improve immune recovery following autologous stem cell infusion, increase the ALC 15, and may improve clinical outcomes.

We previously evaluated immune mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) in a mouse model using IL-2, with or without rhG-CSF. (10) In contrast to the use of rhG-CSF alone, mobilization with the combination of IL-2 and rhG-CSF yielded highly functional lymphocytes that demonstrated increased cytotoxicity against CML (K562) and NHL (Daudi) tumor cells. These results demonstrated enhanced myeloma cytotoxicity of progenitor cells mobilized with IL-2 and rhG-CSF, when compared with rhG-CSF alone. In follow up to this animal model, we developed a Phase I clinical trial using a novel immune mobilization regimen that combined IL-2 and growth factors.

We previously demonstrated that when IL-2 was added to growth factors in ex vivo expansion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC’s), a subset of CD8+ T cells acquired the ability to kill tumor cells using a unique NK cell activating receptor called NKG2D.(11) This specialized subset of CD8+ T cells, labeled NKG2D+CD8+ T cells, recognized and killed myeloma cells in a non-MHC restricted manner that was independent of the T cell receptor (TCR).(11) While many tumor cells down regulate the MHC expression, thereby escaping MHC-restricted and TCR-dependent tumor cell killing, malignant cells up regulate NKG2D ligand expression. (12), (13) The selective expression of NKG2D ligands on malignant cells makes this specialized NKG2D+CD8+ T cell population a potential candidate for adoptive cellular therapy for patients with multiple myeloma. The goal of our clinical trial was to mobilize a significant number of cytotoxic lymphocytes, especially NKG2D+CD8+ T cells, as well as CD34+ progenitor cell. We were specifically interested in the increase in the number of these specialized NKG2D+CD8+ T cells within the collected cellular product in patients mobilized on this clinical trial using IL-2 and growth factors.

We will describe the clinical and laboratory results from the myeloma patients treated on a clinical trial evaluating immune mobilization of autologous peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC).

3. METHODS

3.1. Immune mobilization treatment regimen

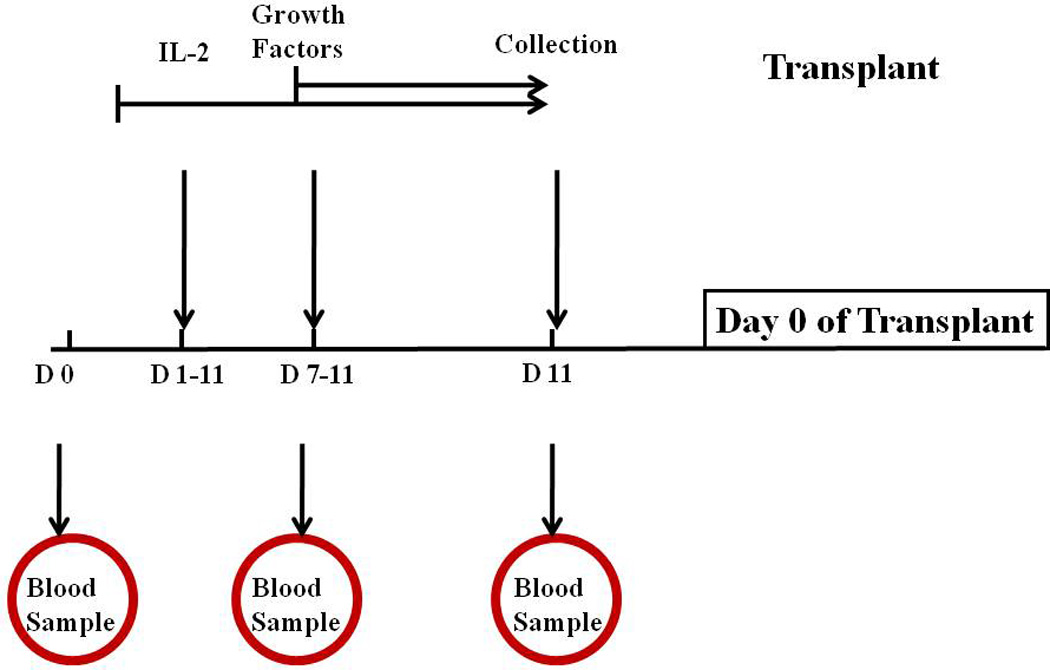

We designed an immune mobilization trial examining dose-escalated IL-2 (Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, San Diego, CA) in combination with GM-CSF (Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Pittsburgh PA) and rhG-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), as previously described. (14) (11) (Figure 1) Briefly, eligible patients between the ages of 17–70 years, with a Karnofsky status ≥ 80 %, were required to have confirmed multiple myeloma with therapy-sensitive disease. The endpoints of this trial were to determine if immune mobilization would increase the number of lymphocytes and improve cytotoxic function of the lymphocytes within the mobilized cells, and yield sufficient number of CD34+ progenitor cells.

Figure 1.

Immune mobilization treatment schema. IL-2 was administered on Day 1 through Day 11. Growth factors were administered on Day 7 and continued to Day 11. Stem cell collection began on day 11 of mobilization. Blood samples were obtained from patients on Days 0 (before starting therapy), Day 7 and Day 11. Growth Factors = G-CSF and GM-CSF; D= Day.

Treatment with IL-2 began at 0.6 × 106 IU/m2 (Level 1) administered as a daily subcutaneous injection for 11 days. (Table 1) On Day 7 of mobilization treatment, rhG-CSF (5 µg/kg/day) and GM-CSF (7.5 µg /kg/day) were started with a daily subcutaneous dose of each medication and both were continued until completion of leukapheresis. On Day 11 of therapy, leukapheresis was initiated if the peripheral blood CD34+ cell number was > 5 CD34+ cells/µl. Daily leukapheresis of approximately 15–20 liters of whole blood (approximately 3.5–4.5 total blood volumes over the course of 300 minutes) were performed. The goal was to collect ≥ 3 × 106 CD34+ progenitor cells/kg. The hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) were either used in experiments the same day or cryopreserved in Human AB serum with 10%DMSO and stored at −140° C.

Table 1.

IL-2 Dose escalation and administration

| IL-2 Dose level | IU of IL-2 /m2/Day |

|---|---|

| Level 0 | 0.3 × 106 |

| Level 1 | 0.6 × 106 Starting Dose |

| Level 2 | 1.0 × 106 |

| Level 3 | 1.5 × 106 |

| Level 4 | 2.0 × 106 |

Length of administration for each IL-2 dose level was 11 days. The starting dose was Level 1

Blood samples were obtained from patients prior to starting therapy, on Day 7 of mobilization (after 7 days of IL-2) and on Day 11 of mobilization (after 11 days of IL-2 and 5 days of growth factor support). Patients who received mobilization with rhG-CSF alone served as our control group. Bone marrow aspirates from patients were obtained before initiating therapy or when indicated during their treatment course. Normal marrow was obtained from volunteer patients. All patients signed an IRB- approved consent prior to donations.

3.2. Cell lines

A human myeloma cell line (RPMI8226) and a human leukemia cell line (K562) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, Herndon, VA) and supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS from Gemini Bio-products, West Sacramento, CA), 2mM L-Glutamine, 100U/ml Penicillin, 100ug/ml Streptomycin (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA).

3.3. Flow cytometry analyses

Cell surface phenotype of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was examined using flow cytometry with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies directed against T lymphocyte markers (CD3, CD4, CD8), an NK cell marker (CD56), the IL-2 receptor (CD25), and an NK cell activating receptor (NKG2D). Phenotypes were analyzed using FACScan or FACSCanto (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) using a standard lymphocyte gate and recorded as percent of positive cells within the specified population. Data were analyzed using Cell quest (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and FlowJo software (Tri star INC., Chatsworth, CA).

3.4. Cytotoxicity assays

We used two methods to test cytotoxicity and to determine the mechanism of tumor cell killing. A standard chromium release assay was performed at three effector to target ratios (E:T : 100:1, 20:1, and 4:1) as previously described.(15) A myeloma cell line RPMI8226), a leukemia cell line (K562) or patients’ autologous myeloma cells served as targets.

An alternative cytotoxicity assay, a CFSE-based assay, was used when patients’ effector cell numbers were limited. RPMI 8226 myeloma cell lines or K562 CML cell lines were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) conjugated to FITC, at 5µM for 6 minutes at 4°C in the dark. CFSE-based cytotoxicity assay was performed using purified CD8+ T cells as effector cells and CFSE-labeled cell lines as targets at a E:T ratio of 50:1 and 100:1 at 37C for 5 hours. Monensin, a Na+/H+ antiporter, was added for the last 4 hours of culture to block intracellular protein transport. After 5 hours of incubation, cells were labeled with anti-NKG2D (APC) and Anti-CD8 (APC-Cy7) and anti-CD107a (PE), and Propidium Iodide (PI) to identify dead cells, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Dead cells were identified as those doubly labeled with CFSE-FITC and PI.

3.5. Ex vivo expansion of myeloma patients’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC): a method to enrich for NKG2D+CD8+ T cells

We previously developed an ex vivo expansion process that enriched for NKG2D+CD8+ T cells, using mobilized PBMC from myeloma patients.(15) These ex vivo expanded NKG2D+CD8+ T cells were used as effector cells in vitro. Briefly, PBMC were cultured in serum-free AIM V medium (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The lymphocyte-enriched cell population was removed and cultured in serum-free AIM V media supplemented with IL-2 (1000IU/ml; Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, San Diego, CA) and OKT3 (500ng/ml; Ortho Biotech Products, Raritan, NJ) every other day for 7 days. Cell viability was determined by Trypan Blue, using either a hemocytometer or an automated cell counter (Cellometer AutoT4 PLUS, Nexelom Biosciences LLC Lawrence, MA). Cell expansion and phenotype was determined using flow cytometry (FACScan or FACSCanto, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and percent positive cells within a lymphocyte gate were recorded.

3.6. CD107a expression on CD8+ T cells

CD107a (LAMP-1) is a marker for degranulation of activated CD8+ T cells. Degranulation is the release of cytotoxic molecules from secretory granules within activated lymphocytes, to destroy tumor cells or microorganisms. NKG2D+CD8+ T cells were analyzed for degranulation by assessing the expression of CD107a by flow cytometry. The relationship between CD107a upregulation on NKG2D+CD8+ T cells and cytotoxic activity of these cells was assessed. Cryopreserved PBMC from myeloma patients were isolated, as previously described.(15) The PBMC were then expanded for 7 days using IL-2 (1000IU/ml) and OKT3 (500ng/ml), a process that enriches for NKG2D+CD8+ T cells. First, CD8+ T cells were isolated using a magnet-activated automated cell separation system (AutoMACS, Miltenyi Biotec AG, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were labeled with 40µl of CD8+ sorting microbeads at 4°C for 15 minutes. Cells were then washed with 4ml of staining buffer and resuspended in 500 µl MACS buffer, and transferred to a 15ml tube. After magnetic separation, purified CD8+ cells were labeled with anti-NKG2D (APC) and Anti-CD8 (APC-Cy7) and anti-CD107a (PE) in presence of IL-2 at 50U/ml.

3.7. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses for differences observed in each experiment were determined using the Student’s t-test at the 95% confidence interval. Graph Pad PRISM 5 statistical software, (La Jola, CA) or Microsoft Excel, (Redmond WA) was used.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Summary of clinical results

We accrued eleven multiple myeloma patients to this phase I clinical trial. These clinical results were previously published. (11) Ten patients completed the full course of treatment. The median number of CD34+ cells/kg collected was 3.6 × 106 cells/kg (range of 1.9 – 6.6 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg). All patients engrafted after transplant without delay. The median number of days for neutrophil engraftment was 12.3 days (range: 9–14 days), and 10.5 days for platelet recovery (range: 0–17 days). There were no treatment-related mortalities and grade 2 (moderate) toxicities or greater were minimal and included: back pain (n=2 patients), fever (n=2 patients), nausea (n=1 patient), chills (n=1 patient), anorexia (n=1 patient), diarrhea (n=1 patient), fluid retention (n=1 patient), and vascular leak (n=1 patient).

4.2. Immune mobilization results in ample CD34+ cells and effector cell numbers

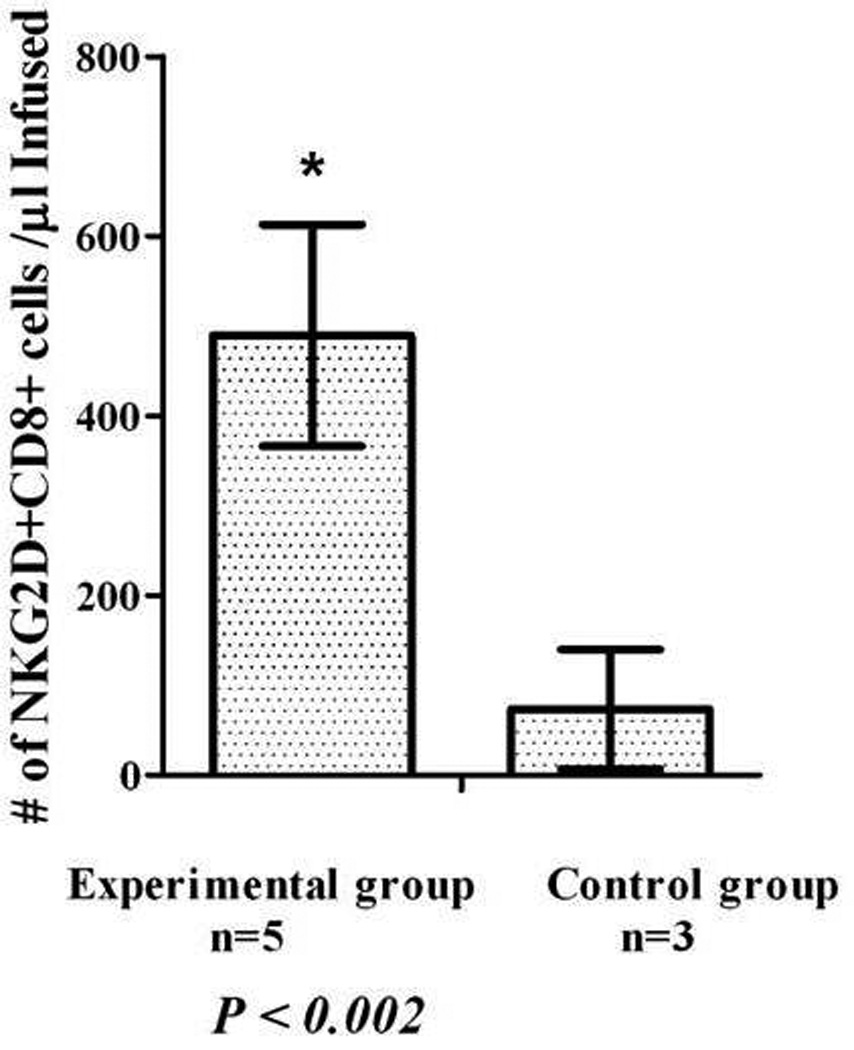

The immune mobilization regimen markedly increased the number of NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells mobilized, and subsequently infused into patients, when compared to controls (P< 0.002). (Figure 2) When IL-2 dose levels were combined, this immune mobilization regimen yielded a significant number of CD34+ cells (median: 3.6 × 106 cells/kg; range: 1.9– 6.6 × 106 cells/kg) and mononuclear cells (median: 10.5 × 108; range: 3.8 – 21 ×108 MNC/kg). (Table 2) Although patient numbers were limited, there was no detrimental effect on CD34+ cell mobilization based on IL-2 dose.

Figure 2.

Immune mobilization increases the number NKG2D+CD8+ T Cells. The number of NKG2D+CD8+ T cells collected in patients receiving immune mobilization with IL-2 and growth factors (n=5; experimental group) compared with patients receiving mobilization with G-CSF alone (control group; n=3 (P< 0.002)’

Table 2.

Immune mobilization: number of CD34+ cells and PBMC’s mobilized

| CD34+cells/kg × 106 Median (range) | MNC cells/kg × 108 Median (range) |

Number of Leukocytaphereses Median (range) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (n=5) | 2.6 (1.9 – 3.5) | 8.7 (6.4 – 21) | 2 (2–3) |

| Level 2 (n=3) | 3.7 (3.2 – 4.4) | 8.9 (3.8 – 9) | 2 (1–2) |

| Level 3 (n=3) | 4.4 (1.9 – 6.6) | 14 (4. 3 – 19) | 2 (1–3) |

| Combined Il-2 Dose Levels (n=11) | 3.6 (1.9–6.6) | 10.5 (3.8–21) | 2 (1–3) |

MNC=Mononuclear cells

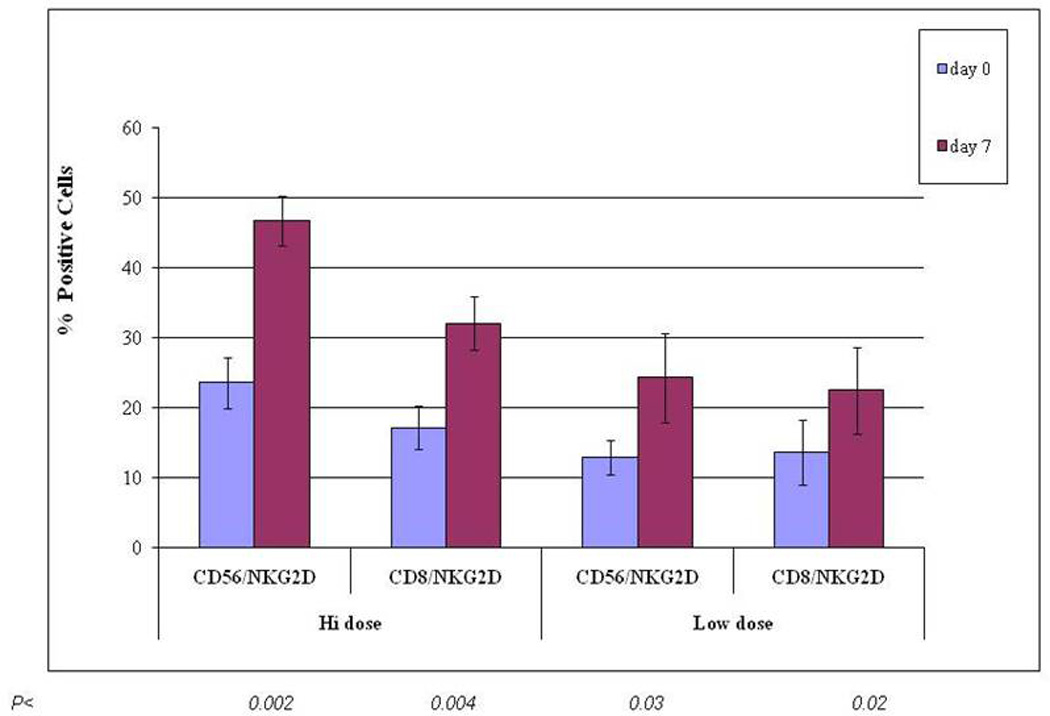

We tested the effect of IL-2 dose on the in vivo NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells, as well as CD56+ NK cells within the mobilized product. Low dose IL-2 (6 × 105 IU/m2/day) increased NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells in the apheresis product, by approximately 1.5-fold, when compared to baseline (P < 0.02). High dose IL-2 (1.5 × 106 IU/m2/day) increased NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells by more than 2-fold, when compared to baseline (P < 0.004). (Figure 3) Low dose IL-2 (6 × 105 IU/m2/d) and high dose IL-2 (1.5 × 106 IU/m2/d) increased NKG2D expression on CD56+ NK cells (P < 0.03 and 0.002, respectively).

Figure 3.

IL-2 Upregulates in vivo NKG2D expression on CD8+ T Cells and CD56+ NK cells. Patients were treated at different dose levels of IL-2. “Hi dose” IL-2 = 1.5 × 106 IU/m2/d; “Low Dose” IL-2 = 6 × 105 IU/m2/d. P values compare baseline (Day 0) results to Day 7 of Mobilization. (n = 3 patients per IL-2 dose level).

4.3. Functional abilities of the immune mobilized NKG2D+CD8+ T cells

4.3.1. Cytotoxicity of the mobilized cells

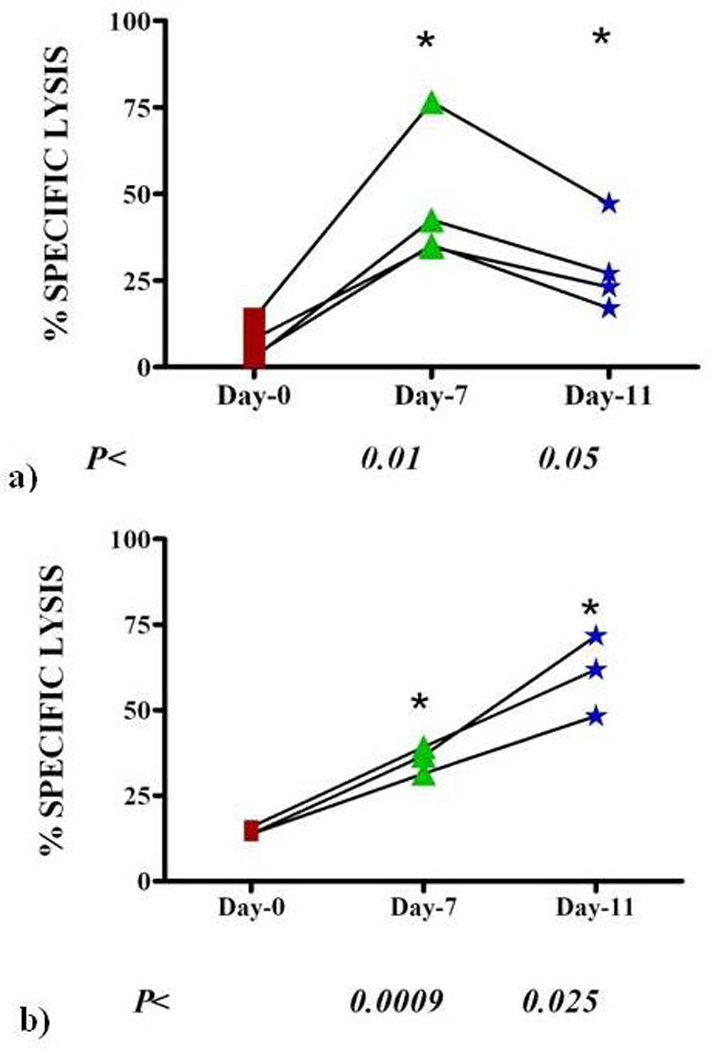

This immune mobilization regimen resulted in an increased number of NKG2D+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells that demonstrated enhanced lytic ability against human tumor cells. There was increased lysis of the RPMI 8226 myeloma cells by patients’ cytotoxic T cells after 7 days of IL-2 treatment (P<0.01) and this lysis was sustained at Day 11 or the day of collection (P < 0.05). (Figure 4a) Patients’ cytotoxic T cells also effectively lysed K562 cells, a CML cell line that lacks Class I expression, confirming an NKG2D-dependent, MHC Class I-non-restricted mechanism of tumor cell lysis. (Figure 4b)

Figure 4.

Enhanced cytotoxicity of myeloma patients’ PBMC. A chromium release cytotoxicity assay was used to test the activity of patients’ mobilized effector cells against a human myeloma cell line, RPMI8226 at an E:T of 20:1 (n= 5 patients per group) (a) and against a human CML cell line, K562, at an E:T of 20:1 (n= 5 patients per group) (b). (Percent specific lysis of tumor cells were comparable in each IL-2 dose group, therefore, cytotoxicity results were combined. P values represent statistical significance in comparing day 7 and day 11 to day 0 (baseline) specific lysis.

To further confirm that tumor cell killing occurs primarily via the specific interaction between NKG2D receptor and its ligands, we used an anti-NKG2D antibody to block the receptor in patients’ NKG2D+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. When NKG2D was blocked, there was a significant reduction in specific tumor cell lysis (P< 0.016). (Data not shown) (16)

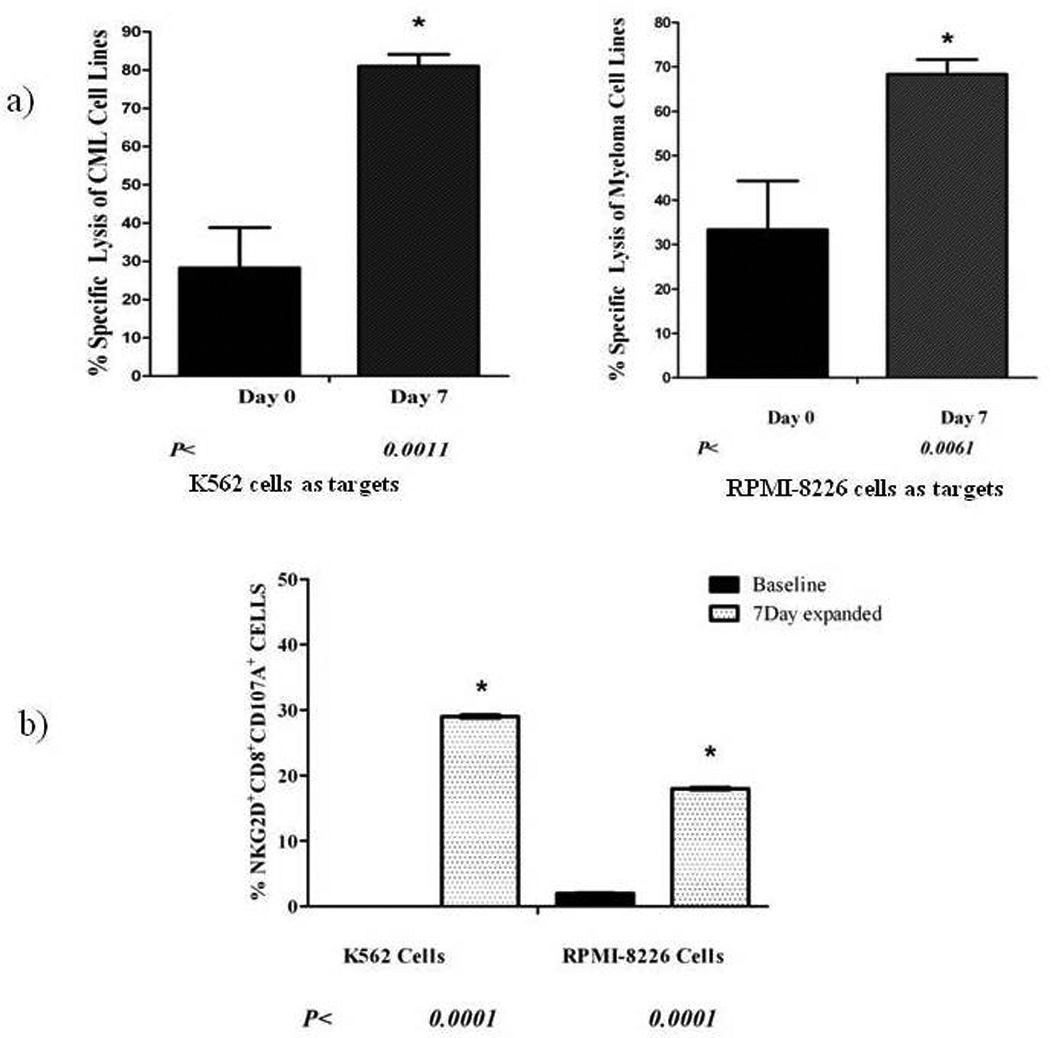

4.3.2. Degranulation of the mobilized cells

To understand the mechanism of activation and tumor cell killing, we measured degranulation of NKG2D+CD8+ T cells by their CD107a expression, at baseline (before ex vivo expansion) and after 7 days of ex vivo expansion with IL-2 and OKT3. After ex vivo expansion, the patients’ CD8+ T cells upregulate NKG2D expression and these NKG2D+CD8+ T cells specifically lyse tumor cells via increased degranulation. (Figure 5) The increased expression of CD107a is consistent with degranulation of NKG2D+CD8+ T cells, suggesting that NKG2D+CD8+ T cells use degranulation to induce apoptosis in tumor cells.

Figure 5.

Ex vivo Expansion increases NKG2D-dependent tumor cell lysis via NKG2D+CD8+ T Cell degranulation. A demonstrates increased tumor cell lysis by NKG2D+CD8+ T cells after 7 days of ex vivo expansion. P values represent statistical significance when comparing specific lysis of target cells by NKG2D+CD8+ T cells at baseline and at day 7 of expansion. Targets include a CML cell line (K562) and a Myeloma cell line (RPMI8226). B demonstrates that, along with an increase in tumor cell lysis, there is a significant increase in CD107a expression, suggesting degranulation of NKG2D+CD8+ T cells. These results indicate that, along with lysis of tumor targets, NKG2D+CD8+ T cells’ degranulation induces apoptosis in tumor cells. P values represent statistical significance when comparing degranulation in NKG2D+CD8+ T cells at baseline and after 7 days of expansion.

5. DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that a mobilized stem cell product containing an increased number of lymphocytes, would improve immune recovery following autologous stem cell infusion, increase the ALC 15, and may improve clinical outcomes. Our data demonstrate that CD8+ T lymphocytes upregulate surface expression of NKG2D in vivo during immune mobilization, rendering highly effective lymphocytes, especially, NKG2D+CD8+ T cells that recognize NKG2D ligands on target cells and aggressively lyse myeloma cells. The clinical results from this phase I clinical trial have been described previously, (11) and indicate that immune mobilization significantly increased the number of NKG2D+ CD8+ T cells (P< 0.004), CD56+ T cells (p< 0.002), and CD3+ CD8+ T cells, within the mobilized product, when compared to a control group. There was significant increase in the lysis of myeloma cells by patients’ cytotoxic T cells after mobilization. These NKG2D+CD8+ T cells are highly cytotoxic when tested against either autologous myeloma cells or tumor cell lines. (16) Our results demonstrate an MHC-I and TCR-independent mechanism of tumor lysis by these NKG2D+CD8+ T cells. Blocking the NKG2D receptor prevented myeloma cell killing. (17) More importantly, we show that NKG2D+CD8+ T cells derived from patients with myeloma recognize and kill autologous myeloma cells. (16).

Results from Porrata et al. support the critical role of the immune system in the survival of myeloma patients. A strong correlation between a higher ALC15 following transplantation and improved survival has been previously established. (2, 3, 5–9, 18–22) Substantial data support the importance of NKG2D receptor in the function of the immune system against various types of cancer. (23–26) NKG2D ligands are upregulated on most tumor cells, but not on healthy cells. (17, 23) (24) (27, 28) Animal studies further support NKG2D-mediated recognition and tumor lysis. Mice bearing tumors that express very low levels of NKG2D ligands develop aggressive disease since these malignant cells escape immune surveillance. In contrast, mice whose tumor cells express high levels of NKG2D ligands are protected from progressive disease. (29)

The majority of tumors are sensitive to immune responses that are triggered by the NKG2D activating receptor. A potential approach to enhance NKG2D-mediated immunity is to upregulate the expression of NKG2D on CD8+ effector T cells, or to stimulate NKG2D ligand expression on tumor cells. One of the medications that are currently used to treat myeloma, including bortezomib, increase NKG2D ligand expression, which may further enhance this targeted therapy. (30) No clinical trials have examined the role of immune mobilization or its effects on in vivo NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells. Our mobilization treatment regimen results in an improved mobilized stem cell product containing an increased number of NKG2D+CD8+ T lymphocytes, which may improve immune recovery, increase the ALC15 and possibly improve clinical outcomes in myeloma patients.

Immune mobilization is a novel form of therapy. We postulate that the increased number and function of the NKG2D+CD8+ T cells within the autologous graft may offer a clinical benefit by aggressively eliminating residual malignant cells in vivo. Our studies introduce a successful method of NKG2D upregulation on patients’ effector cells that demonstrate an attractive model for targeted tumor immunotherapy in myeloma patients. We demonstrate a clinically applicable approach with minimal toxicity and no detrimental effect on CD34+ progenitor cell mobilization. The results of our novel immune mobilization regimen indicate a promising future for the development of a targeted therapy against myeloma that may improve clinical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored in part by a grant from Dartmouth Medical School and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (KRM), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Grant 6061-06 (KRM), R21 CA112761 (KRM, MSE), R01CA130911 (CLS) and R01CA095648 (MSE), and Microbiology & Immunology COBRE Grant P20 RR16437. The research was also funded through an unrestricted research grant from Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horowitz MM. Report on state of the art in blood and marrow transplantation. CIBMTR Newsletter. 2002:7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrata LF, Gertz MA, Inwards DJ, Litzow MR, Lacy MQ, Tefferi A, Gastineau DA, Dispenzieri A, Ansell SM, Micallef IN, Geyer SM, Markovic SN. Early lymphocyte recovery predicts superior survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2001;98:579–585. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porrata LF, Litzow MR, Inwards DJ, Gastineau DA, Moore SB, Pineda AA, Bundy KL, Padley DJ, Persky D, Ansell SM, Micallef IN, Markovic SN. Infused peripheral blood autograft absolute lymphocyte count correlates with day 15 absolute lymphocyte count and clinical outcome after autologous peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:291–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porrata LF, Gertz MA, Geyer SM, Litzow MR, Gastineau DA, Moore SB, Pineda AA, Bundy KL, Padley DJ, Persky D, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Snow DS, Markovic SN. The dose of infused lymphocytes in the autograft directly correlates with clinical outcome after autologous peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2004;18:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensinger W, DiPersio JF, McCarty JM. Improving stem cell mobilization strategies: future directions. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:181–195. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Sohn HJ, Kim S, Lee JS, Kim WK, Suh C. Early lymphocyte recovery predicts longer survival after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:1037–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiwase DK, Hiwase S, Bailey M, Bollard G, Schwarer AP. Higher infused lymphocyte dose predicts higher lymphocyte recovery, which in turn, predicts superior overall survival following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazitt Y. Immunologic profiles of effector cells and peripheral blood stem cells mobilized with different hematopoietic growth factors. Stem Cells. 2000;18:390–398. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-6-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesana C, Carlo-Stella C, Regazzi E, Garau D, Sammarelli G, Caramatti C, Tabilio A, Mangoni L, Rizzoli V. CD34+ cells mobilized by cyclophosphamide and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) are functionally different from CD34+ cells mobilized by G-CSF. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:561–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma UN, Yankelevich B, Hodgson J, Mazumder A. Effect of the in vivo priming regimen for peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) mobilization on in vitro generation of cytotoxic effectors by IL-2 activation of PBSC in a murine model. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:265–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meehan KR, Talebian L, Wu J, Hill JM, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Sentman CL, Ernstoff MS. Immune mobilization of autologous blood progenitor cells: direct influence on the cellular subsets collected. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:1013–1021. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.515580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6879–6884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coudert JD, Held W. The role of the NKG2D receptor for tumor immunity. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meehan KR, Wu J, Bengtson E, Hill J, Ely P, Szczepiorkowski Z, Kendall M, Ernstoff MS. Early recovery of aggressive cytotoxic cells and improved immune resurgence with post-transplant immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:695–703. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meehan KR, Wu J, Webber SM, Barber A, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Sentman C. Development of a clinical model for ex vivo expansion of multiple populations of effector cells for adoptive cellular therapy. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:30–37. doi: 10.1080/14653240701762398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meehan KR. The NK Activating Receptor NKG2D on CD8+T cells Plays a Critical Role in Identifying and Killing Autologous Myeloma Cells. 2011 doi: 10.1111/trf.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu JY, Ernstoff MS, Hill JM, Cole B, Meehan KR. Ex vivo expansion of non-MHC-restricted cytotoxic effector cells as adoptive immunotherapy for myeloma. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:141–148. doi: 10.1080/14653240600620218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gertz MA, Kumar SK, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Dingli D, Gastineau DA, Winters JL, Litzow MR. Comparison of high-dose CY and growth factor with growth factor alone for mobilization of stem cells for transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:619–625. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosman JA, Stiff P, Moss SM, Sorokin P, Martone B, Bayer R, van Besien K, Devine S, Stock W, Peace D, Chen Y, Long C, Gustin D, Viana M, Hoffman R. Pilot trial of interleukin-2 with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for the mobilization of progenitor cells in advanced breast cancer patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy: expansion of immune effectors within the stem-cell graft and post-stem-cell infusion. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:634–644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Gast GC, Vyth-Dreese FA, Nooijen W, van den Bogaard CJ, Sein J, Holtkamp MM, Linthorst GA, Baars JW, Schornagel JH, Rodenhuis S. Reinfusion of autologous lymphocytes with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces rapid recovery of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after high-dose chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:58–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hock BD, Haring LF, Ebbett AM, Patton WN, McKenzie JL. Differential effects of G-CSF mobilisation on dendritic cell subsets in normal allogeneic donors and patients undergoing autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:733–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porrata LF, Litzow MR, Tefferi A, Letendre L, Kumar S, Geyer SM, Markovic SN. Early lymphocyte recovery is a predictive factor for prolonged survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2002;16:1311–1318. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barber A, Zhang T, Sentman CL. Immunotherapy with chimeric NKG2D receptors leads to long-term tumor-free survival and development of host antitumor immunity in murine ovarian cancer. J Immunol. 2008;180:72–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber A, Zhang T, Megli CJ, Wu J, Meehan KR, Sentman CL. Chimeric NKG2D receptor-expressing T cells as an immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:1318–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verneris MR, Karami M, Baker J, Jayaswal A, Negrin RS. Role of NKG2D signaling in the cytotoxicity of activated and expanded CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2004;103:3065–3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker J, Verneris MR, Ito M, Shizuru JA, Negrin RS. Expansion of cytolytic CD8 (+) natural killer T cells with limited capacity for graft-versus-host disease induction due to interferon gamma production. Blood. 2001;97:2923–2931. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eagle RA, Traherne JA, Ashiru O, Wills MR, Trowsdale J. Regulation of NKG2D ligand gene expression. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanca T, Correia DV, Moita CF, Raquel H, Neves-Costa A, Ferreira C, Ramalho JS, Barata JT, Moita LF, Gomes AQ, Silva-Santos B. The MHC class Ib protein ULBP1 is a non-redundant determinant of leukemia/ lymphoma susceptibility to {gamma}{delta} T-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diefenbach A, Hsia JK, Hsiung MY, Raulet DH. A novel ligand for the NKG2D receptor activates NK cells and macrophages and induces tumor immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:381–391. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi J, Tricot GJ, Garg TK, Malaviarachchi PA, Szmania SM, Kellum RE, Storrie B, Mulder A, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Barlogie B, van Rhee F. Bortezomib down-regulates the cell-surface expression of HLA class I and enhances natural killer cell-mediated lysis of myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:1309–1317. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]