Abstract

Myiasis is the infestation of living vertebrates by fly larvae that feed for at least part of their development on the host's dead or living tissues, body substances, or ingested food. The occurrences of traumatic myiasis in humans and animals in urban and rural environments represent serious economic and public health concerns. This study reports a 49-year-old tracheostomized man undergoing chemotherapy treatment who was parasitized in the hospital in São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, by larvae of the screwworm, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in the thoracic cavity.

Keywords : Calliphoridae, ivermectin, myiasis, public health

Introduction

The Diptera Calliphoridae family is one of the main vectors of myiasis in vertebrates. The larvae of these flies feed on the host's dead or living tissue, body substances, or ingested food during part or all of their immature period (Guimarães and Papavero 1999).

Myiasis is an infestation that affects animals, including humans, causing serious economic and public health problems (Queiroz et al. 2005; Batista-da-Silva et al. 2009). According to Guimarães and Papavero (1999), the type of infestation can be classified by the characteristics of the larva and the damage that it causes: the obligate species parasitize living tissues while the facultative species parasitize necrotic tissues in living individuals. Extensive or chronic wounds or advanced stage wounds with frequent exposure are commonly infested by Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). In the literature, myiasis of humans has been associated with low socioeconomic status, alcoholism, mental or neurological diseases, poor personal hygiene, patients with varicose ulcers, diabetes, malnutrition, advanced stages of cancer, pediculosis, immunosuppression, patients with STD, patients with gingivitis, and other lesions in the oral cavity and advanced age (Albernaz 1933; Kaminsky 1993; Verettas et al. 2008). Other factors such as the presence of domestic animals, mendicancy, unhealthy environments, and even debilitated and bedridden patients also contribute to the emergence of new cases (Batista-da-Silva et al. 2009, 2011).

This study presents a case report of a man with tracheostomy undergoing chemotherapy at the National Cancer Institute (INCA-RJ), hospitalized in a public hospital in São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for the treatment of a secondary disease, where he was then parasitized by fly larvae causing obligate myiasis.

Materials and Methods

The patient was a 49-year-old single man who resided in an urban area of São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He was an ex-alcoholic, bedridden, tracheostomized due to carcinoma of the neck, and was undergoing chemotherapy at the National Cancer Institute-RJ (INCA). During the winter of 2008 (June), he was temporarily hospitalized in a ward of a public hospital in São Gonçalo for the treatment of a secondary disease.

After eight days of hospitalization, the patient developed an infestation of fly larvae in the thoracic cavity (Figures 1A, 1B). This infestation was the result of oviposition by flies that entered through open unscreened hospital windows.

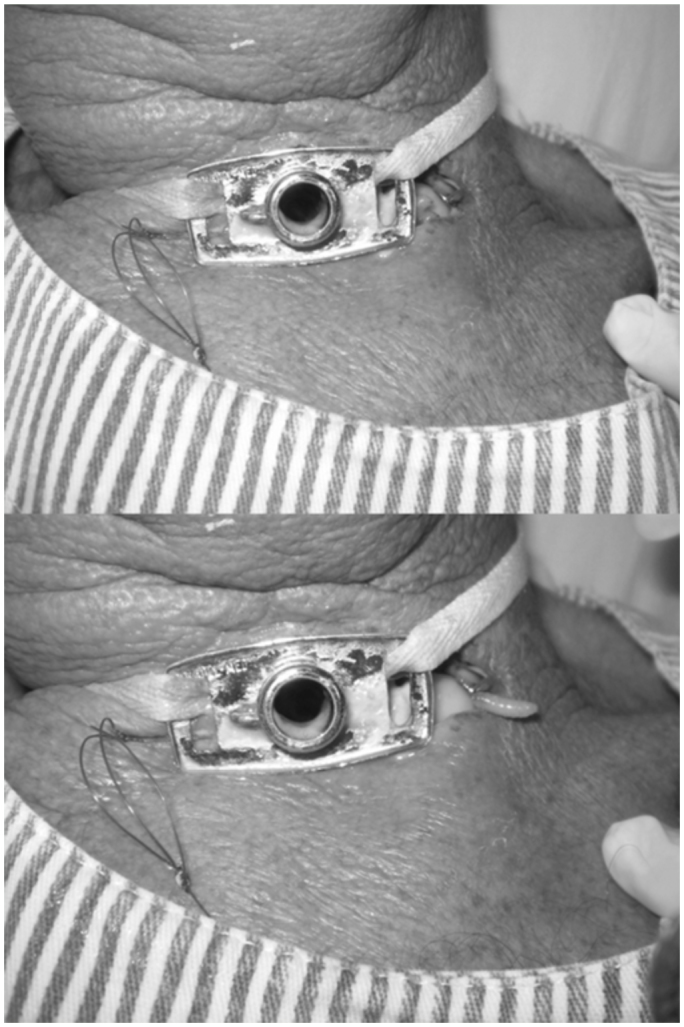

Figure 1.

Human myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax in a man with tracheostomy; (A) larva inside the trachea and (B) larva coming out of the trachea. High quality figures are available online.

Medical staff prescribed ivermectin (12 mg/54 kg) in a single oral dose according to description, dosage, and directions to kill the larvae. The patient, who at the time was in a collective ward, was moved to a single room with air-conditioning (21 °C). A total of 32 larvae (third instar) were collected and placed in individual pots and covered with cotton under environmental conditions in a ventilated area to wait for adult emergence. After emergence, adults were sent to the Laboratory of Leishmaniasis Transmitters (Department of Medical and Forensic Entomology) at the Institute Oswaldo Cruz IOC / FIOCRUZ, RJ, Brazil, to be identified in accordance with the key to genera and species (Mello 2003). Temperature and RH (http://satelite.cptec.inpe.br 2008) were collected for twelve days; mean and standard deviations were calculated for the same data during the pupal stage until the emergence of the adults.

Results

All 32 larvae that were collected from the patient, the bed, and off the floor of the ward were in the third instar, and all had pupated. During this stage, the pupae, under environmental conditions in a ventilated area, were observed daily to see if the variables (temperature and RH) would interfere with the pupal stage or whether there would be any delayed effects caused by the ivermectin on the insects. The total pupation period lasted 12 days for all larvae, with an average temperature of 19.9 — 3.21 °C and 82 — 13.95% RH. All individuals were identified as belonging to species C. hominivorax.

The use of ivermectin to kill third instar larvae in the patient did not interfere in its life cycle; however, the lower winter temperatures increased the pupal stage, which normally lasts an average of eight days (Neves et al. 2000). In contrast, the average RH was favorable to the development of larvae and emergence of adult flies.

Discussion

The patient was undergoing chemotherapy treatment for cancer. Complete laryngectomy (removal of the larynx) results in the loss of physiological voice and definitive tracheostomy (artificial opening in the trachea below the larynx). As preservation of voice quality is a top priority, sometimes radiotherapy is used first, leaving surgery until later if radiotherapy is not sufficient to control the tumor (INCA 2010).

Open wounds and bodily orifices that emit odors of natural secretions are major factors in susceptibility to myiasis (Batista-da-Silva et al. 2011), as they provide a favorable environment for the attraction and oviposition of flies. A bedridden patient is possibly at a higher risk for infestation by fly larvae, a suggestion supported by Smith and Clevenger (1986), who reported that the risk of contracting myiasis increases when the patient is immobile or debilitated. Considering that the patient reported in this study presented an infestation by third instar fly larvae on the eighth day of hospitalization, it is possible that the infestation occurred on the third (72 hours) or fourth day (96 hours) after hospitalization. This provides strong confirmatory support for the results of Hira et al. (2004), where two patients in Kuwait had an infestation more than three days after hospitalization, and according to these authors this case may be considered nosocomial (hospital-acquired) by definition.

Myiases caused by several species of fly larvae and acquired inside the hospital (nosocomial) have been reported in different parts of the world. Smith and Clevenger (1986) reported the occurrence of fly maggots in the nasal cavity of an unconscious 64-year-old man who had been admitted to hospital 18 days earlier in a diabetic hyperosmolar coma. The larvae were identified as C. macellaria, an organism commonly associated with myiasis in the United States (Smith and Clevenger 1986). Hira et al. (2004) reported two cases of facultative myiasis in a hospital in Kuwait City; one a case of nasopharyngeal myiasis caused by Lucilia sericata and the other a cutaneous myiasis caused by Megaselia scalaris. Hardy (1951) also reported larvae of the M. scalaris invading a one-year-old surgical site on the chest of a patient in Hawaii.

The use of ivermectin to kill the larvae has been reported by several authors, and depending on its application (usage) it results in a significant reduction of larvae in infested wounds. Ivermectin is a semi-synthetic antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces avermitilis (Shinohara et al. 2004). Its use is well-documented in large animals for the control of gastrointestinal and lung parasites, as well as to control infestations of fly larvae. Ivermectin blocks the nerve impulses in the nerve endings by releasing gamma-aminobutyric acid, binding to receptors and causing paralysis and death of larvae (Campbell 1985). Although the literature points out the efficiency of ivermectin in the treatment of myiasis caused by larvae of C. hominivorax, this unique case reports an unsuccessful treatment with ivermectin of a cancer patient with a third instar larvae infestation. It is possible that ivermectin might be effective against first and second instars and much less effective against more mature third instar larvae.

According to Graham (1985), early results suggested that ivermectin may be ineffective against C. hominivorax, but more recent studies demonstrated that it can produce a significant reduction in the incidence of navel and scrotal myiasis due to C. hominivorax (Benitez et al. 1997; Lombardero et al. 1999). There has been an increasing number of publications reporting that a subcutaneous injection of doramectin (200 µg/kg) was up to 100% effective as a C. hominivorax prophylactic, preventing infestation of artificial wounds, umbilical or castration wounds of calves, and infestation of post-parturient cows for up to 12–14 days post-treatment (Moya-Borja et al. 1997; Anziani et al. 2000). Caproni et al. (1998) reported a persistent efficacy of doramectin and ivermectin in the prevention of natural C. hominivorax infestations in cattle castrated 10 days after treatment. The study was conducted in Brazil to compare the persistent efficacy of a single subcutaneous injection of doramectin and ivermectin at a dose rate of 200 µg/kg in the prevention of myiasis caused by C. hominivorax larvae in cattle castrated 10 days after treatment and exposed to natural infection in the field. Doramectin had an efficacy higher than 90% and ivermectina had an efficacy of less than 50% (Caproni et al. 1998). Anziani et al. (2000) showed that doramectin provided a reduction in myiasis of 90.9 and 83.3% at 12 and 15 days after induced infestations of C. hominivorax in calves, respectively, compared to the saline control treatment (p < 0.01). In contrast, there were no significant differences in the number of calves with myiasis between those treated with the ivermectin formulations or the saline control.

Besides the fact that ivermectin had no effect on third instar larvae observed in this work, another important aspect observed here is the emergence of all adult flies, demonstrating the absence of any delaying effect of ivermectin on the C. hominivorax pupae. Only the low winter temperatures may have caused an increase in the pupal stage. The mean temperature was 19.9 — 3.21 °C with 100% emergence in 12 days, which was very similar to data obtained by Elwaer and Elowni (1991), where pupation occurred at a temperature of ∼ 20 °C, and had 94% emergence under controlled conditions.

Since the patient had no contact with alcohol, tobacco, or antibiotics during hospitalization for treatment of a secondary disease, it is possible that treatment with ivermectin is inefficient against third instar larvae of C. hominivorax.

The occurrence of a case of myiasis caused by C. hominivorax acquired inside the hospital (nosocomial) indicates a degree of neglect of the medical service and ignorance of the medical staff on how to control this parasite in a hospital environment. The primary factor for infestation was from flies that entered through the open, unscreened window. To avoid similar cases in future, it is imperative that windows screens be used in hospital settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient and those responsible that agreed to participate in this study by signing a term of accordance for the divulgation of data and images and so complying with the existing code of ethics. Additional thanks to David Graham Straker for the English revision and to Instituto Oswaldo Cruz — IOC/ FIOCRUZ for financial support.

References

- Albernaz PM. De algumas localizações raras de miíases. Revista Otolaringológica. 1933;1(3):226. [Google Scholar]

- Anziani OS, Flores SG, Moltedo H, Derozier C, Guglielmone AA, Zimmermann GA, Wanker O. Persistent activity of doramectin and ivermectin in the prevention of cutaneous myiasis in cattle experimentally infested with Cochliomyia hominivorax. Veterinary Parasitology. 2000;87(2–3):243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-da-Silva JA, Abádio HC, Queiroz MMC. Miíase humana por Dermatobia hominis (Linneaus Jr.) (Diptera, Cuterebridae) e Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera, Calliphoridae) em Sucessão Parasitaria. Entomologistas do Brasil. 2009;2(2):61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-da-Silva JA, Moya-Borja GE, Queiroz MMC. Factors of susceptibility of human myiasis caused by the New World screw-worm, Cochliomyia hominivorax in São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Journal of Insect Science. 2011;11:14. doi: 10.1673/031.011.0114. Available online, http://www.insectscience.Org/11.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez Usher C, Cruz J, Carvalho L, Bridi A, Farrington D, Barrick RA, Eagleson J. Prophylactic use of ivermectin against cattle myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858). Veterinary Parasitology. 1997;72(2):215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WC. Ivermectin: An update. Parasitology Today. 1985;1(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(85)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caproni LJR, Umehara O, Goncalves LCB, Moro E. Persistent efficacy of doramectin and ivermectin in the prevention of natural Cochliomyia hominivorax infestations in cattle castrated 10 days after treatment. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária. 1998;7(1):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Elwaer OR, Elowni EE. Studies on the screwworm fly Cochliomyia hominivorax in Libya: Effect of temperature on pupation and eclosion. Parasitology Research. 1991;77(1):48–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00934384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham OH. Symposium on eradication of the screwworm from the United States and Mexico. Miscellaneous Publications of the Entomological Society of America. 1985;62:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães JH, Papavero N. Myiasis in man and animals in the Neotropical region, 1st edition. Plêiade; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DE. A case of apparent human myiasis. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 1951;14:212–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hira PR, Assad R, Oshaka G, A1-Ali F, Iqbal J, Mutawali KEH, Disney RHL, Hall MJR. Myiasis in Kuwait: nosocomial infections caused by Lucilia and Megaselia species. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004;70(4):386–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). São Paulo. 2008. Available online, http://satelite.cptec.inpe.br.

- Institute Nacional do Cancer. Rio de Janeiro. 2010. Available online, http://www2.inca.gov.br.

- Kaminsky RG. Nasocomial myiasis by Cochliomyia hominivorax in Honduras. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;87(2):199–200. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardero OJ, Moriena RA, Racioppi O, Billaudots A, Maliandi FS. Comparacion de la accion curativa y preventiva de la ivermectina y doramectina en la miasis umbilical de terneros con infestacion natural, en Corrientes (Argentina). Veterinaria Argentina. 1999;16(158):588–591. [Google Scholar]

- Mello RP. Chave para identificação das formas adultas das espécies da familia Calliphoridae (Diptera, Brachycera, Cyclorrhapha) encontradas no Brasil. Entomologia y Vectores. 2003;10(2):255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Borja GE, Muniz RA, Umehara O, Goncalves LCB, Silva DSF, Mckenzie ME. Protective efficacy of doramectin and ivermectin against Cochliomyia hominivorax. Veterinary Parasitology. 1997;72(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves DP, Melo AL, Genaro O, Linardi PM. Parasitologia Humana, 10a edição. Atheneu; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz MMC, Ribeiro PC, Cabrai MMO, Borja GEM, Mello RP, Norberg NA. Miíases Humanas por Cochliomyia hominivorax no Estado do Rio de Janeiro e Suas Conseqüências. Parasitologia Latinoamericana. 2005;60(2):167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara EH, Martini MZ, Neto HGO, Takahashi A. Oral myiasis treated with ivermectin: case report. Brazilian Dental Journal. 2004;15(1):79–81. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402004000100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Clevenger RR. Nasocomial nasal myiasis. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 1986;110:439–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verettas DAJ, Chatzipapas CN, Drosos GI, Xarchas KC, Staikos C, Chloropoulou P, Kazakos KI, Ververidis A. Maggot infestation (myiasis) of external fixation pin sites in diabetic patients. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008;102(9):950–952. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]