Abstract

α-Synuclein is a presynaptic neuronal protein that is linked genetically and neuropathologically to Parkinson's disease (PD). α-Synuclein may contribute to PD pathogenesis in a number of ways, but it is generally thought that its aberrant soluble oligomeric conformations, termed protofibrils, are the toxic species that mediate disruption of cellular homeostasis and neuronal death, through effects on various intracellular targets, including synaptic function. Furthermore, secreted α-synuclein may exert deleterious effects on neighboring cells, including seeding of aggregation, thus possibly contributing to disease propagation. Although the extent to which α-synuclein is involved in all cases of PD is not clear, targeting the toxic functions conferred by this protein when it is dysregulated may lead to novel therapeutic strategies not only in PD, but also in other neurodegenerative conditions, termed synucleinopathies.

α-Synuclein protofibrils disrupt cellular homeostasis and mediate neuronal death via intracellular targets. Secreted α-synuclein may exert deleterious effects on neighboring cells.

The first link of Parkinson's disease (PD) to α-synuclein was also the first conclusive demonstration of a genetic defect leading to PD, and thus has historical and conceptual value. Although familial contribution to the disease was discussed by some, it was felt to be minor at best by most. The tangible discovery of a gene defect linked to PD in particular families was a ground-breaking discovery, as it opened the door to a flood of studies investigating the genetic base of the disorder, culminating in more recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS), that, remarkably, have made a full circle back to the origins of the molecular genetic era of PD; it turns out that one of the major genes identified as linked to sporadic PD is none other than SNCA, the gene encoding for α-synuclein.

A parallel story that has developed over the years is the abundant abnormal α-synuclein pathology that characterizes neuropathological specimens derived not only from PD patients, but also patients with other neurodegenerative conditions, collectively termed “synucleinopathies.” The ability to model abnormal α-synuclein accumulation in various cellular and animal models has led to the study of the consequences of such accumulation, to the deciphering of the molecular pathways involved, and to the identification of potential therapeutic targets. Such targets may prove of general utility, and provide the basis for future therapeutics in most forms of PD, and, potentially, other synucleinopathies.

GENETICS OF PD AND OTHER DISORDERS WITH LINKS TO SYNUCLEINOPATHIES

In 1997, Polymeropoulos et al. reported the first specific genetic aberration linked to PD in a large Italian kindred, and in some Greek familial cases. The mutation corresponded to a G209A substitution in the SNCA gene encoding for α-synuclein, resulting in an A53T amino acid change. The pattern of inheritance was autosomal-dominant, and the disease was early-onset, usually in the 40s. Although there was some initial skepticism, based on the fact that the threonine was the amino acid in position 53 in the rodent SNCA homolog, this was set aside following the identification of two more point mutations in SNCA, leading to A30P and E46K amino acid changes, which were associated with autosomal-dominant PD (Kruger et al. 1998; Zarranz et al. 2004). The next landmark study that linked SNCA to PD through a different mechanism identified triplications of the SNCA locus in separate families with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (Singleton et al. 2003). This led to a potential total of a duplication of the α-synuclein load in such patients, and this was confirmed later at the protein level (Miller et al. 2004). Other families were subsequently described that harbored duplications of the gene, which was similarly associated with autosomal-dominant disease (Chartier-Harlin et al. 2004). Interestingly, a gene dosage effect exists, in that triplication cases are earlier onset and have a more severe course compared to the duplication cases (Fuchs et al. 2007).

When a specific genetic defect is identified in rare familial cases, it is almost a reflex reaction to look at the same gene in the sporadic disease, with the hope of identifying polymorphisms that may be linked to the disease in association studies. This has not been particularly successful in other diseases, but in the case of PD and the SNCA gene this approach has borne fruit. Initial studies focused on the Rep1 polymorphic region located approximately 10 kB upstream of the SNCA transcriptional initiation site. Particular polymorphisms in this region conferred a relative risk for sporadic PD in initial association studies, which were replicated and then confirmed in a large metanalysis (Maraganore et al. 2006). Others studies found associations of PD with 3′ regions of the gene (Mueller et al. 2005; Mizuta et al. 2006). Targeted association studies are, however, prone to false positives; therefore, it is very important that the link of SNCA to sporadic PD has been confirmed through large unbiased GWAS. SNCA, and, in particular, the 3′ region, has been a consistent hit in such studies, and represents, of the links identified, probably the most robust one (Nalls et al. 2011).

The conclusion from these genetic studies is that SNCA is linked to both rare familial and sporadic PD from a genetic standpoint. It is notable that the association of SNCA variants to disease has now also been extended to multiple-system atrophy (MSA), another prototypical synucleinopathy, which is invariably sporadic (Al-Chalabi et al. 2009; Scholz et al. 2009).

THE INVOLVEMENT OF α-SYNUCLEIN IN THE NEUROPATHOLOGICAL PICTURE OF PD AND RELATED DISORDERS

The genetic link of SNCA to PD in 1997 led investigators to rapidly develop appropriate antibodies against α-synuclein and use them in histopathological sections of PD patients. α-Synuclein turned out to be robustly expressed within Lewy bodies (LBs), and, in particular, in the “halo” of the inclusions (Spillantini et al. 1997, 1998; Baba et al. 1998). In fact, α-synuclein immunohistochemistry is currently the gold standard in the neuropathological evaluation of PD. With repeated studies, three major insights emerged: (1) α-synuclein pathology in PD is not confined to the cell soma, but is also prominent in neuritic processes, (2) it is widespread in various brain regions in PD, and (3) it is present in a number of other synucleinopathies, such as MSA, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLBs), many cases of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (the so-called LB variant of AD), neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) type I, pure autonomic failure (PAF), and even a subtype of essential tremor (reviewed in Kahle 2008). The distribution of the pathology at the cellular and regional level is different in each disease.

Braak et al. (2003), in their seminal study of the staging of PD pathology, used α-synuclein immunohistochemistry in a large number of autopsy cases. Based essentially on α-synuclein neuritic pathology (“Lewy neurites”), they suggested a six-stage scheme in which the pathology begins first at the olfactory bulb and the dorsal vagal nucleus and gradually follows an ascending course, culminating in widespread α-synuclein pathology at the later stages, involving associative cortical regions. Notably, substantia nigra is only affected in stage 3 of this scheme. Although there have been criticisms against this hypothesis (Burke et al. 2008), and it does not explain the absence of clinical symptoms in subjects who on autopsy have widespread α-synuclein pathology, or the clinical picture of DLB, it appears to hold up for the majority, but not all, of cases examined in large cohorts of LB cases (Dickson et al. 2010). What is important to note here is that overall in the PD brain the majority of abnormally deposited α-synuclein is in neuritic processes. The presence of α-synuclein in LBs is likely the tip of the iceberg. In fact, Kramer and Shulz-Schaeffer (2007), using a modified protocol termed protein aggregate filtration, showed in DLB cases a remarkable degree of aberrant neuritic α-synuclein pathology, in the virtual absence of LBs.

Overall, it is clear that abnormal α-synuclein deposition occurs early in PD. Given the fact that such pathology may develop secondarily, for example, owing to iron mishandling in NBIA type I, we cannot be certain that it is a primary factor in the disease process. However, the generally quite defined pattern of α-synuclein pathology in PD, the cellular and animal models of α-synuclein overexpression that will be discussed, and, most importantly, the combination with the genetic data mentioned above, suggest that this aberrant deposition is the driving force in PD pathogenesis. Such deposition, as mentioned, may be subtle and difficult to detect in the absence of elaborate immunohistochemical techniques that, it is hoped, will become more widely applicable and available.

THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF α-SYNUCLEIN

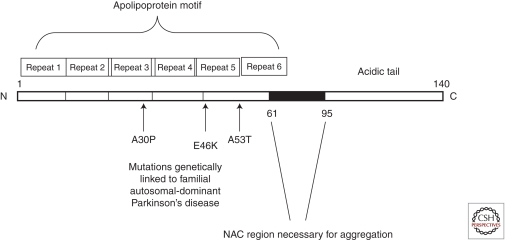

The SNCA gene encodes for a 140 amino acid protein, which in aqueous solutions does not have a defined structure, hence the term “natively unfolded protein.” α-Synuclein, however, does form α-helical structures on binding to negatively charged lipids, such as phospholipids present on cellular membranes, and β-sheet-rich structures on prolonged periods of incubation. The protein is composed of three distinct regions: (1) an amino terminus (residues 1–60), containing apolipoprotein lipid-binding motifs, which are predicted to form amphiphilic helices conferring the propensity to form α-helical structures on membrane binding, (2) a central hydrophobic region (61–95), so-called NAC (non-Aβ component), which confers the β-sheet potential, and (3) a carboxyl terminus that is highly negatively charged, and is prone to be unstructured (Fig. 1). There are at least two shorter alternatively spliced variants of the SNCA gene transcript, but their physiological and pathological roles have not been well characterized (Maroteaux and Scheller 1991; Ueda et al. 1993; Maroteaux et al. 1988).

Figure 1.

Schemtic structure of α-synuclein.

α-Synuclein is a member of the synuclein family of proteins, which also include β- and γ-synuclein. What largely sets apart α-synuclein from the other members structurally is the NAC region. All three members of the family are predominantly neuronal proteins that under physiological conditions localize preferentially to presynaptic terminals (George 2002). There are some reports of extranigral β- and γ-synuclein neuritic pathology in synucleinopathies, but, if it exists, it does not appear to be widespread (Galvin et al. 1999). Interestingly, point mutations in β-synuclein have been described in rare cases with DLB (Ohtake et al. 2004), and expression of one of these in a transgenic mouse model-induced neurodegeneration (Fujita et al. 2010). On the other hand, wild-type (WT) β-synuclein has been found to be protective in various settings against α-synuclein-mediated neurodegeneration (Hashimoto et al. 2001; Park and Lansbury, 2003). It would appear therefore that WT β-synuclein may have neuroprotective properties, but that, under certain situations, it may assume a neurotoxic potential.

α-Synuclein is abundantly expressed in the nervous system, comprising 1% of total cytosolic protein. On immunohistochemistry in normal brains α-synuclein antibodies confer a punctuate neuropil staining pattern, consistent with presynaptic terminal staining, whereas neuronal soma staining is less apparent (Kahle 2008). In presynaptic terminals α-synuclein is present in close proximity, but not within, synaptic vesicles. In fact α-synuclein is also very abundant, for unclear reasons, in erythrocytes and platelets (Barbour et al. 2008). Whether it is expressed at all under physiological conditions in glia is somewhat controversial; it would appear that, if it exists, such expression is present at very low levels (Mori et al. 2002a). The expression of α-synuclein is induced during neuronal development, following determination of neuronal phenotype and establishment of synaptic connections, and lags behind the induction of proteins involved in synaptic structure (Withers et al. 1997; Kholodilov et al. 1999; Murphy et al. 2000; Rideout et al. 2003). Moreover, α-synuclein expression levels are modulated in conditions that alter plasticity or confer injury (George et al. 1995; Kholodilov et al. 1999; Vila et al. 2000). Such data have led to the notion that α-synuclein may be a modulator of synaptic transmission. Examinations of neurophysiological properties of mice null for α-synuclein and of cellular systems in which WT α-synuclein is overexpressed have been instrumental in this regard, as they reveal alterations in neurotransmitter release, which are not always consistent across neuronal systems (Abeliovich et al. 2000; Murphy et al. 2000; Cabin et al., 2002; Larsen et al. 2006). Overall though, it would appear that α-synuclein acts as a subtle break for neurotransmitter release under circumstances of repeated firing. An elegant study by Fortin et al. (2005) showed that fluorescently labeled α-synuclein moves away from the vesicles on neuronal firing, and then gradually returns. These effects may involve transient binding of α-synuclein to the vesicles, whereas α-synuclein may also be involved in vesicular biogenesis, through effects on phosphatidic acid metabolism, and in compartmentalization between resting and readily releasable pools (Murphy et al. 2000). Consistent with a role for α-synuclein at the level of synaptic transmission, α-synuclein modulates profoundly the phenotype of mice null for the presynaptic protein CSP-α (cysteine string protein-α), which show synaptic degeneration (Chandra et al. 2005). It is believed that α-synuclein, through a chaperone-like function, may act in synergy with CSP-α in the assembly of the SNARE complex (Chandra et al. 2005), and this effect may involve, in particular, binding to synaptotagmin-2 (Burree et al. 2010).

Therefore, the main function of α-synuclein would appear to be the control of neurotransmitter release, through effects on the SNARE complex. Recent evidence, to be discussed below, suggests that this physiological function may provide insight into the aberrant function unleashed in disease states.

SYNUCLEINOPATHY MODELS

Based on the genetic and pathological data, attempts have been made to create cellular and animal models in which various forms of α-synuclein are overexpressed. We have elected to not present such models with any great detail here, but rather highlight the inferences gained from such models regarding the potential pathological (and sometimes physiological) effects of α-synuclein. Suffice it to say here, that there are a number of transgenic mice available, in which expression of various forms of α-synuclein is achieved through different promoters, allowing in some cases regional and temporal control of expression. In such mice, there is generally some degree of neurodegneration and LB-like pathology, but it does not involve primarily the dopaminergic system. Some mice develop behavioral phenotypes that could be akin to presymptomatic PD (reviewed by Chesselet 2008). An alternative approach has been the viral-mediated transduction of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra of rodents with α-synuclein, and this has been more successful in modeling the dopaminergic cell death aspect of the disease (Kirik et al. 2002). A number of invertebrate models, including fly (Feany and Bender 2000) and Caenorhabditis elegans (Lasko et al. 2003), have also been created, and have been very useful in testing theories regarding the toxic pathways elicited by aberrant α-synuclein.

THE AGGREGATION POTENTIAL OF α-SYNUCLEIN

The ability of α-synuclein to generate β-sheet structures under certain circumstances generated a lot of enthusiasm, as it provided parallels to the β-sheet structure of β-amyloid, and consequently, a unified pathogenetic basis for the two most common neurodegenerative diseases. Indeed, WT as well as disease-related mutants of α-synuclein form amyloid-like fibrils on prolonged incubation in solution (Conway et al. 2000). It is widely agreed on that such fibrils form the basis of the mature LBs and Lewy neurites (LNs) present in synucleinopathies. In the process of fibril formation various intermediate forms of α-synuclein develop. These are initially soluble oligomeric forms of α-synuclein that assume spherical, ring-, and stringlike characteristics when seen under the electron microscope. Such structures, collectively termed protofibrils, gradually become insoluble and coalesce into fibrils. It is difficult to capture these intermediate structures in cells or in vivo, but their biochemical equivalent is thought to be soluble oligomeric forms, some, but not all, of which are SDS-stable and can be detected on SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels. Other forms, however, can only be captured on native gels or by size-exclusion chromatography (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010a). This cascade of events, starting from the natively unfolded protein and culminating in the mature fibril formation is collectively termed α-synuclein aggregation.

The general consensus in the field is that aggregation is a main pathogenic feature of α-synuclein. This is buttressed by the lack of toxicity conferred by WT β-synuclein or by α-synuclein variants that do not contain the NAC domain and do not form aggregates (Periquet et al. 2007), by the beneficial effects of overxepressing HSPs, which assist in refolding of aggregation-prone proteins, in synucleinopathy models (Auluck and Bonini 2002; Auluck et al. 2002; Klucken et al. 2004), and by the protection conferred in cellular models of α-synuclein overexpression by reagents that inhibit or neutralize aggregated species (Vekrellis et al. 2009; Bieschke et al. 2010). However, the protective effects of HSP overexpression are not always apparent (Shimshek et al. 2010). There is less agreement as to which particular species are neurotoxic. A predominant idea is that some of the early soluble oligomeric species have such a potential. This is based on the following pieces of data:

-

(1)

A53T and A30P α-synuclein form more protofibrils than the WT protein, whereas only A53T forms more readily mature fibrils; however, E46K α-synuclein forms less protofibrils than the WT, therefore there is no simple correlation that can explain everything using this scheme, which is based on in vitro cell-free systems (Conway et al. 2000; Fredenburg et al. 2007).

-

(2)

Dopamine and its metabolites act as inhibitors of the conversion of protofibrils to mature fibrils in vitro and in vivo, presumably through the formation of dopamine/α-synuclein adducts (Conway et al. 2001; Mazzulli et al. 2006; Tsika et al. 2010), suggesting that the preferential vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to the pathogenic process of PD may be attributable to the enhanced presence of soluble oligomers (although, surprisingly, mouse nigral neurons, which contain more oligomers, appear relatively resistant to transgenic α-synuclein-mediated neurodegeneration).

-

(3)

In cellular systems and in vivo, the presence of soluble oligomers, and not frank inclusions, generally correlates best with neurotoxicity (Gosavi et al. 2002; Lo Bianco et al. 2002). Two major studies provided support to this idea, as they showed enhanced neurotoxicity both in cell culture and in vivo with artificial mutants of α-synuclein that favored the formation of soluble oligomers over mature fibrils (Karpinar et al. 2009; Winner et al. 2011). It should be noted, however, that the issue is not settled; the protofibrils are heterogeneous, “off pathway” oligomers that do not lead to toxicity may exist, and frank inclusions have the potential of being neurotoxic themselves over time, especially if present in axons, where they can block neuronal trafficking or “suck in” essential neuronal components. On the other hand, if the protofibril theory is correct, enhancing inclusions could be viewed as a method to remove the toxic intermediate oligomeric species, and this has been attempted with some success in cellular models (Bodner et al. 2006).

α-SYNUCLEIN POSTTRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS AND INTERACTIONS

α-Synuclein may be modified by phosphorylation, oxidation, nitrosylation, glycation, or glycosylation. Of all such modifications, the best studied is phosphorylation. Antibodies specific to S129-phosphorylated α-synuclein prominently decorate LBs in synucleinopathies (Fujiwara et al. 2002). Although the initial idea, which appeared to be buttressed by experiments in transgenic flies, was that such phosphorylation enhanced α-synuclein-soluble oligomers (but actually decreased α-synuclein inclusions) and neurotoxicity (Chen et al. 2005, 2009); subsequent studies have cast doubt on this notion, providing contradictory results (Gorbatyuk et al. 2008; Paleologou et al. 2008; Azeredo da Silveira et al. 2009). In fact, it may be that S129 phosphorylation, which occurs minimally under physiological circumstances, occurs after the fact in already formed LBs (Paleologou et al. 2008). Enhancing α-synuclein phosphatase activity was, however, protective against α-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity, suggesting a causal detrimental role of α-synuclein phosphorylation in the disease process (Lee et al. 2011). Polo-like kinases appear to be the physiological kinases for α-synuclein S129 phosphorylation (Inglis et al. 2009; Mbefo et al. 2010). S87 is another phosphorylation site for α-synuclein, and S87-P α-synuclein is also apparent within LBs, but its pathological significance is unclear (Paleologou et al. 2010). Phosphorylation on α-synuclein tyrosine residues has also been reported and may act in opposing fashion to S129 phosphorylation, at least in Drosophila (Chen et al. 2009).

A number of studies in cell-free systems and in cell culture have shown that α-synuclein can be oxidized, and this seems to drive its oligomerization (Lee et al. 2002; Betarbet et al. 2006; Mirzaei et al. 2006; Qin et al. 2007). Iron and dopamine appear to exert a similar effect, although whether this is a direct interaction or mediated by oxidation is less clear (Ostrerova-Golts et al. 2000; Conway et al. 2001; Kostka et al. 2008; Leong et al. 2009). The potent oxidant 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) promoted stable soluble oligomers, inhibiting their conversion to fibrils; such stable soluble oligomers were highly toxic, favoring again the soluble oligomer toxicity theory (Qin et al. 2007). In a similar vein, nitration of α-synuclein has been reported; in fact, an antibody specifically generated against nitrosylated α-synucelin decorates LB-like pathology (Giasson et al. 2000). Monomeric and dimeric nitrated α-synuclein promoted fibril formation (Hodara et al. 2004), whereas oligomeric nitrated α-synuclein actually inhibited it, stabilizing as soluble oligomers (Uversky et al. 2005), suggesting complex effects of nitrosylation on α-synuclein aggregation. As with S129 phosphorylation, it is possible that the intense nitrosylation of α-synuclein within LB-like structures occurs after the fact.

Given the fact that oxidative/nitrative stress induced by environmental factors, including mitochondrial toxins, has been heavily implicated in PD, oxidation- or nitration-induced α-synuclein oligomerization has attracted attention, as a point of potential convergence between environmental and genetic factors leading to the disease. It should be noted, however, that α-synuclein aggregation could be dissociated from mitochondrial toxicity-induced death (Liu et al. 2008), arguing against simplistic linear pathways to neurodegeneration, and raising the issue whether in certain instances the abundant α-synuclein-related pathology may be an epiphenomenon, and not causally related to neuronal dysfunction and death. Similar inferences can be taken from a study in proteasomal inhibitor-treated neurons, where the β-sheet-like pathology of α-synuclein was dissociated from death (Rideout et al. 2004).

Another modification that may be important is carboxy-terminal truncation of α-synuclein, leading to fragments lacking part or the whole of the acidic tail (Li et al. 2005). These fragments appear to be more prone to fibrillization (Kim et al. 2002; Murray et al. 2003). Calpain, one of the enzymes thought to perform such processing, is especially interesting given its calcium dependence and localization at presynaptic terminals (Mishizen-Eberz et al. 2003, 2005).

α-Synuclein is quite promiscuous in its binding properties, and may bind various proteins in neuronal cells, including components of dopamine metabolism, such as tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and the dopamine transporter (DAT), modulating their function (Ostrerova et al. 1999; Perez et al. 2002; Wersinger and Sidhu 2003; Wersinger et al. 2003; Peng et al. 2005). There are quite a few reports suggesting that through such binding to various proteins, α-synuclein may exert pro- or antiapoptotic effects (Ostrerova et al. 1999; da Costa et al. 2000; Jin et al. 2011), although no effect on programmed neuronal cell death has been shown in mice null for α-synuclein (Stefanis et al. 2004). Interestingly, however, these mice are resistant to the well-known mitochondrial neurotoxin MPTP, through mechanisms that are still not deciphered, but may involve steps both upstream of and downstream from mitochondrial dysfunction (Dauer et al. 2002). Such mice are also resistant against neuroinflammation-induced nigral degeneration conferred by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Gao et al. 2008), suggesting that endogenous α-synuclein is somehow involved in such death pathways.

A number of interactions of α-synuclein with other proteins have been implicated in its aggregation potential; most notable amongst these is synphilin-1, a protein identified through a yeast-two-hybrid screen as an AS-interacting protein, which promotes α-synuclein aggregation and inclusion formation (Engelender et al. 1999). Interestingly, transgenic expression of synphilin-1 on the background of A53T α-synuclein transgenic mice attenuates neurodegeneration, as assessed by indices of cell death and gliosis, while enhancing inclusion formation, suggesting that promoting α-synuclein inclusion formation is neuroprotective (Smith et al. 2010).

Interactions of α-synuclein with lipids may be important not only for their physiologic functions, but also for their aberrant effects. Regarding the former, it is interesting to note that sequestration of the fatty acid arachidonic acid away from the SNARE complex by α-synuclein has been suggested to underlie its inhibitory effect on neuronal transmission (Darios et al. 2010), and that alterations in levels of key enzymes in lipid signaling, such as PLD2 and PLA2, may underlie the phenotype in SNCA null microglia, which are overreactive but lack phagocytic potential (Austin et al. 2006, 2011). Regarding the latter, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been shown to enhance oligomerization and neurotoxicity of α-synuclein (Perrin et al. 2001; Sharon et al. 2003; Assayag et al. 2007).

GAIN-OF-FUNCTION AND ACCUMULATION OF α-SYNUCLEIN

The notion that enhanced α-synuclein levels are causative in PD pathogenesis is derived from the familial SNCA multiplication cases showing a dose-dependent correlation of α-synuclein load to the PD phenotype, the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance for the point mutations, the accumulation of α-synuclein in synucleinopathy brains, and the demonstration that features of the disease can be mimicked by WT α-synuclein overexpression in various models. Consistent with this idea, α-synuclein protein levels are increased with aging in the substantia nigra, and correlate with decreased TH immunostaining (Chu and Kordower 2007). However, it should be noted that there is insufficient evidence that there is a generalized excess of α-synuclein in PD brains. In fact, mRNA studies have been quite contradictory in this regard, with some even showing a decrease of SNCA expression in PD nigra (Dachsel et al. 2007). Protein levels are not obviously increased overall in PD brains, although clearly there is induction of insoluble components, including monomeric and oligomeric species. A comprehensive study of multiple brain areas showed that membrane-associated monomeric α-synuclein levels were only modestly increased in the substantia nigra, and not in other brain regions, of PD patients compared to controls; even so, the levels in some PD cases were within the spectrum of control values. In contrast, in MSA, the membrane-associated α-synuclein increase was robust in vulnerable brain regions (Tong et al. 2010). It may of course be that neurons with the highest expression levels of α-synuclein are most vulnerable and succumb early in the disease process, giving their place to glia, thus confounding the results. To partly circumvent this issue, Gründemann et al. (2008) performed laser-capture microdissection studies, and reported a considerable increase of SNCA expression in surviving nigral neurons derived from PD brains compared with controls. However, this increase did not appear to be specific for SNCA (Gründemann et al. 2008). Therefore, the issue is still open.

An indirect way of approaching this is by assessing whether polymorphic SNCA variants that confer disease risk in association studies alter α-synuclein levels in model systems. In initial studies, the Rep1 polymorphism associated with the disease led to increased SNCA transcriptional activity in neuronal cell lines (Chiba-Falek and Nussbaum 2001); this finding has been confirmed in mice (Cronin et al. 2009), and even in the human brain (Linnertz et al. 2009), although in another study an association between Rep1 polymorphisms and α-synuclein mRNA and protein levels in the brain was not apparent (Fuchs et al. 2008). Polymorphisms within the 3′ region may also correlate with AS levels (Fuchs et al. 2008; Mata et al. 2010). Intriguingly, it was reported that risk-conferring alleles at the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) were associated with increased expression of an alternatively spliced form of SNCA (McCarthy et al. 2011), suggesting another mechanism through which gene variations may be linked to the disease.

It is generally assumed that α-synuclein leads to disease through a toxic gain-of-function that is likely inherent in the normal protein when it exceeds a certain level. In apparent agreement with this, α-synuclein null mice, in contrast to transgenic overexpressors, display no overt neuropathological or behavioral phenotype (Abeliovich et al. 2000; Cabin et al. 2002). However, when studied more closely, such mice do have some deficits in the dopaminergic system, in particular, a slightly reduced number of postnatal dopaminergic neurons (Robertson et al. 2004), and a drop of dopaminergic terminals with aging (Al-Wandi et al. 2010). Thus, the theory that part of the PD phenotype might be attributable to the sequestering of physiological α-synuclein in inclusions, which could cause neuronal, and, in particular (in view of the normal function of the protein), synaptic damage, cannot be discarded.

Despite the fact that transcriptional regulation of α-synuclein is so important for PD pathogenesis, little is known about the mechanisms involved. Transcription factors GATA-1 (Scherzer et al. 2008) and ZSCAN21 (Clough and Stefanis 2007; Clough et al. 2009) within Intron 1 have been proposed to play a role as inducers of transcription. In the latter case, a signaling pathway involving ERK/PI3 kinase signaling mediated ZSCAN-induced SNCA transcriptional activation (Clough and Stefanis 2007; Clough et al. 2009). A similar ERK-dependent signaling pathway regulating SNCA production was apparent in enteric neurons (Paillusson et al. 2010). Methylation may be important in SNCA expression, as methylation within Intron 1 suppressed SNCA transcriptional activity, and brains of patients with LB diseases showed decreased methylation within this region, suggesting epigenetic regulation of SNCA expression (Jowaed et al. 2010; Matsumoto et al. 2010). In one study, it was proposed that sequestration of the methylation factor Dnmt1 away from the nucleus by α-synuclein may lead to reduced methylation and enhanced SNCA exression, thus creating a feed-forward loop of SNCA overexpression (Desplats et al. 2011). Posttranscriptional regulation of α-synuclein can also occur through endogenous micro RNAs, which bind to the 3′ end of the gene (Junn et al. 2009; Doxakis 2010). A particularly interesting twist to the effects of familial point mutations in SNCA has been provided by a series of studies that, somewhat counterintuitively, suggest that the expression of the mutant alleles is suppressed, especially in cases with prolonged disease (Markopoulou et al. 1999; Kobayashi et al. 2003), through a mechanism that may involve histone modifications (Voutsinas et al. 2010). Remarkably, Voutsinas et al. (2010) found that the WT allele is induced in a compensatory fashion, and that the total level of SNCA messenger RNA (mRNA) exceeds that of controls, suggesting that total SNCA levels, rather than the presence of the A53T mutant, are responsible for the disease in these cases. Although this study was based on a single patient, it does bring up again the issue of total SNCA levels as the major determinant of toxicity.

In view of the above, a reasonable avenue to attack synucleinopathies may be the lowering of α-synuclein levels. A note of caution is in order here, given the uncertainty about potential neurotoxicity associated with severe reduction of α-synuclein levels, as mentioned above. In fact, Gorbatyuk et al. (2010) found that siRNA-mediated down-regulation of α-synuclein led to quite considerable neurotoxicity within the rat nigral dopaminergic system within a period of 4 wk. In contrast, no toxicity was observed when small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against α-synuclein were injected directly into the monkey nigra, achieving 50%–60% down-regulation of expression (McCormack et al. 2010).

Control of α-synuclein levels can also be achieved at the level of its degradation. α-Synuclein degradation has been controversial, but it appears that the bulk of degradation of at least monomeric WT α-synuclein in neuronal cell systems occurs through the lysosomal pathways of chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) and macroautophagy (Paxinou et al. 2001; Webb et al. 2003; Cuervo et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004; Vogiatzi et al. 2008; Mak et al. 2010). It has been proposed that dysfunction of these degradation pathways may be a contributing factor to PD pathogenesis (Xilouri et al. 2008). α-Synuclein may also be turned over by the proteasome in other experimental settings (Tofaris et al. 2001; Webb et al. 2003). A factor that may play a role is the exact species of α-synuclein studied. In any case, strategies directed toward promoting such endogenous degradation systems to enhance clearance of excess α-synuclein have the advantage that they could also alleviate the aberrant effects of α-synuclein on their function (see below). Indeed, stimulation of macroautophagy through pharmacological or molecular means leads to increased WT α-synuclein clearance and neuroprotection (Webb et al. 2003; Spencer et al. 2009). Another attractive method of enhancing clearance of α-synuclein through the lysosomal pathway may be through immunization (Masliah et al. 2005, 2011).

POTENTIAL PATHOGENIC EFFECTS OF α-SYNUCLEIN: α-SYNUCLEIN AT THE SYNAPSE

Given the physiological role of α-synuclein at the synapse, it is not surprising that studies have identified synaptic effects as significant determinants of α-synuclein-induced neurotoxicity in cell culture and in vivo models based on overexpression of the protein; in some of these cases levels of overexpression are modest, expected to be present in at least the brains of the SNCA multiplication cases. The effects seen include loss of presynaptic proteins, decrease of neurotransmitter release, redistribution of SNARE proteins, enlargement of synaptic vesicles, and inhibition of synaptic vesicle recycling (Chung et al. 2009; Garcia-Reitböck et al. 2010; Nemani et al. 2010; Scott et al. 2010). It is likely that such deficits precede overt neuropathology and are causal in synaptic and neuritic degeneration, although the sequence of synaptic events and the identification of the exact point in the cascade in which aberrant α-synuclein assumes its neurotoxic potential are still elusive.

Given the role of calcium is presynaptic signaling events, it is tempting to speculate that perturbations in calcium homeostasis may play a role in the neuritic degeneration induced by α-synuclein. Indeed, there is some evidence for this, albeit still somewhat fragmentary, implicating primarily α-synuclein oligomers, which could form pores on cellular membranes or alter the properties of voltage-gated receptors, leading to excess calcium influx (Volles and Lansbury 2002; Danzer et al. 2007; Hettiarachchi et al. 2009). Through a similar porelike mechanism, oligomeric AS may also attack synaptic vesicles, leading to leakage of neurotransmitter in the cytosol; in the case of dopamine vesicles, this would mean excess cytosolic dopamine, which could lead to oxidative stress-induced death (Mosharov et al. 2006). Excess intracellular calcium enhanced cytosolic dopamine, and AS was required for death induced by excess dopamine, creating a possible scenario in which intracellular calcium, cystolic dopamine, and α-synuclein interact with each other in a self-feeding cascade leading to neurodegeneration (Mosharov et al. 2009). Another factor that could be important in this setting is calcium-mediated calpain activation that could lead, as mentioned, to carboxy-terminal α-synuclein truncation, consequent oligomerization, and further calcium influx, creating a vicious cycle.

α-SYNUCLEIN AT THE CYTOSKELETON

α-Synuclein may impact cytoskeletal dynamics. Most of the evidence suggests an association of α-synuclein with microtubules. Various investigators have detected an interaction of α-synuclein with tubulin (Alim et al. 2002; Zhou et al. 2010), but the effects reported on tubulin polymerization are conflicting, with others reporting enhanced (Alim et al. 2004; Lin et al. 2009), and others reduced (Lee et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2010) tubulin polymerization as a result of α-synuclein overexpression. Furthermore, tubulin depolymerization may lead to impaired maturation of α-synuclein protofibrils into mature fibrils, which may lead to enhanced neurotoxicity (Lee and Lee 2002). Another factor that may be important is the relationship of α-synuclein to tau, which is likely important in the pathogenesis of sporadic disease, as in GWAS the two corresponding genes are the ones showing the highest association to PD (Nalls et al. 2011). Although tauopathy is not a prominent feature in PD, it is appreciated in certain cases (Kotzbauer et al. 2004). In such cases, α-synuclein and tau pathology may occur in the same cell, but the formed aggregates are separate. In fact, each one of these two proteins has the tendency to seed the aggregation of the other (Giasson et al. 2003). α-Synuclein appears to enhance tau phosphorylation, and this may lead to secondary effects on the microtubular network (Jensen et al. 1999; Haggerty et al. 2011; Qureshi and Paudel 2011).

Furthermore, α-synuclein may bind and influence polymerization of actin, and thus perhaps indirectly affect cellular trafficking and synaptic function; disparate effects on actin were observed between WT and A30P mutant α-synuclein (Sousa et al. 2009). Another aspect that appears to be affected by aberrant α-synuclein, and may be related to the effects on the cytoskeleton, is axonal transport. In an adeno-associated virus (AAV) model of nigral synucleinopathy, early changes before cell death included a diminution at the level of the striatum of motor proteins involved in anterograde transport, and an increase of those involved in retrograde transport (Chung et al. 2009).

α-SYNUCLEIN AND PROTEIN DEGRADATION SYSTEMS

An issue that has attracted a lot of attention is the possibility that aberrant α-synuclein may impact protein degradation systems. This notion is attractive, as a number of neurodegenerative conditions are associated with impairments of protein clearance, and such impairments have the potential to create a vicious loop involving aberrant α-synuclein accumulation. Aberrant α-synuclein, mutant, or under certain circumstances, WT, can induce proteasomal dysfunction in a number of cell-free, cellular, and in vivo settings (Stefanis et al. 2001; Tanaka et al. 2001; Petrucelli et al. 2002; Snyder et al. 2003), although this is not universally observed (Martin-Clemente et al. 2004). It is thought that oligomeric α-synuclein, and, in particular, small soluble oligomeric forms that are themselves degraded by the proteasome, may exert this effect (Lindersson et al. 2004; Emmanouilidou et al. 2010a). This would create the potential for the vicious cycle mentioned above.

Mutant α-synuclein may also aberrantly impact the lysosomes, causing impairment of CMA (Cuervo et al. 2004; Xilouri et al. 2009; Alvarez-Erviti et al. 2010). WT AS, in an adduct with dopamine, can cause a similar effect (Martinez-Vicente et al. 2008). Interestingly, the main proteins involved in CMA, Lamp2a and Hsc70, are diminished in PD brains (Alvarez-Erviti et al. 2010). Such CMA impairment may cause compensatory macroautophagy induction that may be detrimental to neuronal survival (Xilouri et al. 2009). The issue is, however, controversial, as others find that WT α-synuclein actually diminishes macroautophagy, through an inhibitory action at the level of phagophore formation (Winslow et al. 2010).

An interesting issue that relates to α-synuclein degradation and its effects on protein degradation systems is the relationship of PD to Gaucher disease and glucocerebrosidase (GBA). Heterozygote and homozygote carriers of GBA mutations are at an increased risk of developing PD. It is controversial whether this represents a loss-of-function of GBA or a gain-of-function conferred by the mutants. According to some, loss-of-function of GBA is sufficient to induce α-synuclein accumulation and aggregation (Manning-Bog et al. 2010; Mazzulli et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2011), which may occur secondary to lysosomal dysfunction (Mazzulli et al. 2011); others find that α-synuclein accumulates only on overexpression of GBA mutants, favoring a gain of toxic function mechanism (Cullen et al. 2011). The accumulation of substrates such as glycosylceramide owing to GBA loss-of-function may also confer increased tendency of α-synuclein to oligomerize (Mazzulli et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2011); on the other hand, oligomeric α-synuclein may impact on GBA, leading to its dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle of lysosomal dysfunction and aberrant α-synuclein accumulation (Mazzulli et al. 2011).

α-SYNUCLEIN AT THE MITOCHONDRIA AND RELATIONSHIP TO OXIDATIVE STRESS

Many studies now have confirmed that a proportion of α-synuclein, endogenous or overexpressed, resides within mitochondria, and that it causes down-regulation of complex I activity, thus linking α-synuclein with the effects of mitochondrial toxins, and potentially, sporadic PD (Li et al. 2007; Devi et al. 2008; Nakamura et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Loeb et al. 2010). Furthermore, brain mitochondria morphology is disrupted in α-synuclein transgenic mice (Martin et al. 2006). α-Synuclein, potentially in the form of small oligomers, appears to induce mitochondrial fragmentation, which may be responsible for subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction and death (Kamp et al. 2010, Nakamura et al. 2011). α-Synuclein, and especially the mutant form, perhaps through the same mechanism of fragmentation, also induces inappropriate excessive mitophagy, which leads to mitochondrial removal and neuronal death (Choubey et al. 2011). Interestingly, enhancing the expression of PGC-1a, the master transcriptional regulator of nuclearly encoded mitochondrial subunits, which is down-regulated in PD brains, leads to protection against α-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration in cellular models (Zheng et al. 2010).

Through such effects on mitochondria, and especially the complex I inhibition, α-synuclein could potentially induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, oxidative stress, and resultant neuronal death. There is in fact some evidence that α-synuclein overexpression can induce ROS, and that suppressing these through molecular or pharmacological means may be neuroprotective in mammalian (Hsu et al. 2000; Clark et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011) or insect systems (Wassef et al. 2007; Botella et al. 2008).

α-SYNUCLEIN AT THE ER/GOLGI

In a neuronal cell model based on adenoviral expression of α-synuclein, Golgi fragmentation was an early feature and correlated with the appearance of soluble oligomeric species (Gosavi et al. 2002). Smith et al. (2005) observed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as an early event in an inducible model of A53T α-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity, and were able to inhibit death using a pharmacological inhibitor of ER stress, also suggesting that a primary target of α-synuclein may be the ER/Golgi. In a blinded screen in a yeast model, the major class of modulators of α-synuclein toxicity was genes involved in vesicular trafficking (Willingham et al. 2003). This was taken one step further by Cooper et al. (2006), who identified ER-to-Golgi trafficking as the major cellular perturbation in this yeast model, and Rab1, a protein involved in this transition, as a critical determinant of α-synuclein-mediated toxicity in a variety of cellular and in vivo models. Thayanidhi et al. (2010) suggested that in mammalian systems the ER/Golgi transition was delayed owing to an antagonistic effect of α-synuclein on ER/Golgi SNAREs. Overexpression of other Rabs, more closely linked to synaptic vesicular function, such as Rab3A, also prevented dopaminergic toxicity in the α-synuclein C. elegans model, suggesting that these phenomena may more broadly reflect the interaction and effects of α-synuclein on vesicular dynamics (Gitler et al. 2008).

α-SYNUCLEIN IN THE NUCLEUS

Synuclein bears its name from its apparent localization in the nucleus and presynatic nerve terminals (Maroteaux et al. 1988). However, nuclear localization of α-synuclein has only been observed inconsistently (Mori et al. 2002b; Yu et al. 2007); it actually appears that, at least in transgenic mice, α-synuclein phosphorylated at S129 may be preferentially localized in the nucleus (Schell et al. 2009). α-Synuclein has been found to interact with histones on nuclear translocation in nigral neurons in response to the herbicide paraquat (Goers et al. 2003), and to reduce histone acetylation (Kontopoulos et al. 2006). Inhibitors of histone deacetylase (HDAC) rescued α-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity in cell culture and in vivo Drosophila models (Kontopoulos et al. 2006). Furthermore, inhibition of Sirtuin 2, a mammalian HDAC, which led to increased acetylation, was associated with neuroprotection in various models of synucleinopathy, although whether potential acetylation effects on histone were involved was not ascertained (Outeiro et al. 2007).

α-SYNUCLEIN OUTSIDE THE CELL: THE THEORY OF PROPAGATION

Although initially α-synuclein was thought to be a purely intracellular protein, as it lacks a signaling sequence that would direct it to the secretory pathway, it gradually became clear that it could be detected in the conditioned medium of cells and in extracellular fluids, such as plasma and CSF (El-Agnaf et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2005). The mechanism of α-synuclein secretion is not well understood, but it appears to occur through a nonclassical secretory pathway (Lee et al. 2005), possibly within exosomes, endocytic vesicles that are contained within multivesicular bodies and are released on calcium influx (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010b). The existence of extracellular α-synuclein in rodent and human brain interstitial fluid has been confirmed by microdialysis (Emmanouilidou et al. 2011). Importantly, secreted α-synuclein can impact neuronal homeostasis and lead to neuronal death, even at concentrations close to those identified in bodily fluids, and the responsible species, at least in part, appear to be soluble oligomeric (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010b; Danzer et al. 2011). Furthermore, various reports have shown that extracellular α-synuclein can induce inflammatory reactions in glial cells, thus further potentiating neurodegeneration (Zhang et al. 2005; Klegeris et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2010). It should be noted, however, that such studies are often based on high concentrations of recombinant α-synuclein that may not be physiologic. This issue is also touched on by Gendelman and colleagues (Mosley et al. in press).

A related aspect of α-synuclein pathobiology that has attracted a lot of attention is its apparent ability to be uptaken by cells, although, at least in cell culture, this is highly dependent on the cell type and the particular species of α-synuclein and is not easily achieved in intact neuronal cells (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010b). Oligomeric-aggregated α-synuclein species appear to be especially prone to uptake and have the potential to “seed” fibrillization of endogenous α-synuclein (Danzer et al. 2007, 2009, 2011; Luk et al. 2009; Nonaka et al. 2010; Waxman and Giasson 2010; Hansen et al. 2011). This observation has created a lot of excitement, as it could potentially explain the propagation of pathology observed in PD, according to the Braak hypothesis of staging of the disease. Two key in vivo observations support this “prionlike propagation” theory. On the one hand, progenitor cells implanted in the hippocampus of recipient mice transgenic for α-synuclein incorporated host α-synuclein in their cell soma (Desplats et al. 2009), and fetal dopaminergic neurons also showed uptake of host α-synuclein (Hansen et al. 2011); on the other, fetal dopaminergic grafts in humans showed LB pathology many years after implantation, although whether the α-synuclein within the grafted neurons was host-derived could not be determined with certainty (Kordower et al. 2008). An intriguing study has brought together the mitochondrial dysfunction with the α-synuclein propagation theories. Intragastric administration of the complex I inhibitor rotenone led to enteric α-synuclein pathology, which gradually spread to the central nervous system (CNS), including dopaminergic neurons, and caused delayed neurotoxicity, suggesting that, once initiated by mitochondrial dysfunction, α-synuclein aberrant conformations assume an independent propagating seeding and neurotoxic potential (Pan-Montojo et al. 2010). This would be consistent with the findings of early enteric α-synuclein pathology in PD (Braak et al. 2006) and in α-synuclein transgenic mice (Kuo et al. 2010). A note of caution is indicated in the general assumption that seeding is equated with neurotoxicity. In fact, seeding and toxicity of extracellular α-synuclein can be dissociated (Danzer et al. 2007).

α-SYNUCLEIN BIOMARKERS

In view of the importance of α-synuclein in PD pathogenesis, a number of studies have attempted to use measurements of α-synuclein as biomarkers for the disease and for other synucleinopathies. In the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), most studies appear to show a reduction of total α-synuclein levels in PD patients compared with controls (Tokuda et al. 2006; Mollenhauer et al. 2008, 2011; Hong et al. 2010; Kasuga et al. 2010); in fact, a comprehensive study suggested that α-synuclein levels, measured by a sensitive ELISA technique, may help to differentiate synucleinopathies, where α-synuclein is reduced compared with other neurodegenerative conditions, such as tauopathies or amyloidoses (Mollenhauer et al. 2011). In contrast, oligomeric α-synuclein, measured by a specific ELISA method, was higher in PD compared with control CSF (Tokuda et al. 2010), extending previous findings of identification of soluble oligomeric α-synuclein in DLB brain tissue (Paleologou et al. 2009), but this intriguing result awaits replication in a larger cohort. Data from α-synuclein measurements in peripheral tissues/fluids have been inconsistent, and overall peripheral α-synuclein levels, despite the ease of obtaining the material, do not appear to have potential as biomarkers.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

It is clear from the above that α-synuclein represents a valid therapeutic target in PD and possibly in related synucleinpathies. Possible therapeutic strategies that could be envisioned are depicted in Figure 2. Perhaps the most promising strategy would involve small molecules that would have the potential to alter the conformation of protofibrillar forms of α-synuclein and render them nonpathogenic. An example of such natural products could be the green tea derivative EGCG (Bieschke et al. 2010) or the natural product scyllo inositol (Vekrellis et al. 2009). It may be that multiple therapeutic approaches will need to be used, in view of the feed-forward amplification loops involved in the pathogenic effects of α-synuclein.

Figure 2.

Possible targets for therapeutic intervention in PD and related synucleinopathies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L.S. was funded for PD-related research by EC FP7 Programmes NEURASYNC and MEFOPA.

Footnotes

Editor: Serge Przedborski

Additional Perspectives on Parkinson's Disease available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Farinas I, Choi-Lundberg D, Ho WH, Castillo PE, Shinsky N, Verdugo JM, Armanini M, Ryan A, et al. 2000. Mice lacking α-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron 25: 239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A, Dürr A, Wood NW, Parkinson MH, Camuzat A, Hulot JS, Morrison KE, Renton A, Sussmuth SD, Landwehrmeyer BG, et al. 2009. Genetic variants of the α-synuclein gene SNCA are associated with multiple system atrophy. PLoS One 4: e7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alim MA, Hossain MS, Arima K, Takeda K, Izumiyama Y, Nakamura M, Kaji H, Shinoda T, Hisanaga S, Ueda K 2002. Tubulin seeds α-synuclein fibril formation. J Biol Chem 277: 2112–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alim MA, Ma QL, Takeda K, Aizawa T, Matsubara M, Nakamura M, Asada A, Saito T, Kaji H, Yoshii M, et al. 2004. Demonstration of a role for α-synuclein as a functional microtubule-associated protein. J Alzheimers Dis 6: 435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Cooper JM, Caballero C, Ferrer I, Obeso JA, Schapira AH 2010. Chaperone-mediated autophagy markers in Parkinson disease brains. Arch Neurol 67: 1464–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wandi A, Ninkina N, Millership S, Williamson SJ, Jones PA, Buchman VL 2010. Absence of α-synuclein affects dopamine metabolism and synaptic markers in the striatum of aging mice. Neurobiol Aging 31: 796–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assayag K, Yakunin E, Loeb V, Selkoe DJ, Sharon R 2007. Polyunsaturated fatty acids induce α-synuclein-related pathogenic changes in neuronal cells. Am J Pathol 171: 2000–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Bonini NM 2002. Pharmacological prevention of Parkinson disease in Drosophila. Nat Med 8: 1185–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Chan HY, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Bonini NM 2002. Chaperone suppression of α-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson's disease. Science 295: 865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SA, Floden AM, Murphy EJ, Combs CK 2006. α-Synuclein expression modulates microglial activation phenotype. J Neurosci 26: 10558–10563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SA, Rojanathammanee L, Golovko MY, Murphy EJ, Combs CK 2011. Lack of α-synuclein modulates microglial phenotype in vitro. Neurochem Res 36: 994–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeredo da Silveira S, Schneider BL, Cifuentes-Diaz C, Sage D, Abbas-Terki T, Iwatsubo T, Unser M, Aebischer P 2009. Phosphorylation does not prompt, nor prevent, the formation of α-synuclein toxic species in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet 18: 872–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, Tomita T, Nakaya K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Iwatsubo T 1998. Aggregation of α-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol 152: 879–884 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour R, Kling K, Anderson JP, Banducci K, Cole T, Diep L, Fox M, Goldstein JM, Soriano F, Seubert P, et al. 2008. Red blood cells are the major source of α-synuclein in blood. Neurodegener Dis 5: 55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Canet-Aviles RM, Sherer TB, Mastroberardino PG, McLendon C, Kim JH, Lund S, Na HM, Taylor G, Bence NF, et al. 2006. Intersecting pathways to neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease: Effects of the pesticide rotenone on DJ-1, α-synuclein, and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Neurobiol Dis 22: 404–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE 2010. EGCG remodels mature α-synuclein and amyloid-βfibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 7710–7715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner RA, Outeiro TF, Altmann S, Maxwell MM, Cho SH, Hyman BT, McLean PJ, Young AB, Housman DE, Kazantsev AG 2006. Pharmacological promotion of inclusion formation: A therapeutic approach for Huntington’s and Parkinson's diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 4246–4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella JA, Bayersdorfer F, Schneuwly S 2008. Superoxide dismutase overexpression protects dopaminergic neurons in a Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 30: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E 2003. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 24: 197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del Tredici K 2006. Gastric α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson's disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett 396: 67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, Dauer WT, Vonsattel JP 2008. A critical evaluation of the Braak staging scheme for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 64: 485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC 2010. α-Synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329: 1663–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabin DE, Shimazu K, Murphy D, Cole NB, Gottschalk W, McIlwain KL, Chen A, Ellis CE, Paylor R, Lu B, et al. 2002. Synaptic vesicle depletion correlates with attenuated synaptic responses to prolonged repetitive stimulation in mice lacking α-synuclein. J Neurosci 22: 8797–8807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernández-Chacón R, Schlüter OM, Südhof TC 2005. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123: 383–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier-Harlin MC, Kachergus J, Roumier C, Mouroux V, Douay X, Lincoln S, Levecque C, Larvor L, Andrieux J, Hulihan M, et al. 2004. α-Synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson's disease. Lancet 364: 1167–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Feany MB 2005. α-Synuclein phosphorylation controls neurotoxicity and inclusion formation in a Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Nat Neurosci 8: 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Periquet M, Wang X, Negro A, McLean PJ, Hyman BT, Feany MB 2009. Tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of α-synuclein have opposing effects on neurotoxicity and soluble oligomer formation. J Clin Invest 119: 3257–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesselet MF 2008. In vivo α-synuclein overexpression in rodents: A useful model of Parkinson's disease? Exp Neurol 209: 22–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba-Falek O, Nussbaum RL 2001. Effect of allelic variation at the NACP-Rep1 repeat upstream of the α-synuclein gene (SNCA) on transcription in a cell culture luciferase reporter system. Hum Mol Genet 10: 3101–3109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey V, Safiulina D, Vaarmann A, Cagalinec M, Wareski P, Kuum M, Zharkovsky A, Kaasik A 2011. Mutant A53T α-synuclein induces neuronal death by increasing mitochondrial autophagy. J Biol Chem 286: 10814–10824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Kordower JH 2007. Age-associated increases of α-synuclein in monkeys and humans are associated with nigrostriatal dopamine depletion: Is this the target for Parkinson's disease? Neurobiol Dis 25: 134–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, Koprich JB, Siddiqi H, Isacson O 2009. Dynamic changes in presynaptic and axonal transport proteins combined with striatal neuroinflammation precede dopaminergic neuronal loss in a rat model of AAV α-synucleinopathy. J Neurosci 29: 3365–3373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J, Clore EL, Zheng K, Adame A, Masliah E, Simon DK 2010. Oral N-acetyl-cysteine attenuates loss of dopaminergic terminals in α-synuclein overexpressing mice. PLoS One 5: e12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough RL, Dermentzaki G, Stefanis L 2009. Functional dissection of the α-synuclein promoter: Transcriptional regulation by ZSCAN21 and ZNF219. J Neurochem 110: 1479–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough RL, Stefanis L 2007. A novel pathway for transcriptional regulation of α-synuclein. FASEB J 21: 596–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT Jr 2000. Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both α-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson's disease: Implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 571–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Rochet JC, Bieganski RM, Lansbury PT Jr 2001. Kinetic stabilization of the α-synuclein protofibril by a dopamine-α-synuclein adduct. Science 294: 1346–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, Liu K, Xu K, Strathearn KE, Liu F, et al. 2006. α-Synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science 313: 324–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin KD, Ge D, Manninger P, Linnertz C, Rossoshek A, Orrison BM, Bernard DJ, El-Agnaf OM, Schlossmacher MG, Nussbaum RL, et al. 2009. Expansion of the Parkinson disease-associated SNCA-Rep1 allele upregulates human α-synuclein in transgenic mouse brain. Hum Mol Genet 18: 3274–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D 2004. Impaired degradation of mutant α-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 305: 1292–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen V, Sardi SP, Ng J, Xu YH, Sun Y, Tomlinson JJ, Kolodziej P, Kahn I, Saftig P, Woulfe J, et al. 2011. Acid β-glucosidase mutants linked to Gaucher disease, Parkinson disease, and Lewy body dementia alter α-synuclein processing. Ann Neurol 69: 940–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dachsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Gonzalez J, Ross OA, Dickson DW, Farrer MJ 2007. The ups and downs of α-synuclein mRNA expression. Movement Disord 22: 293–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa CA, Ancolio K, Checler F 2000. Wild-type but not Parkinson's disease-related ala-53 → Thr mutant α-synuclein protects neuronal cells from apoptotic stimuli. J Biol Chem 275: 24065–24069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Haasen D, Karow AR, Moussaud S, Habeck M, Giese A, Kretzschmar H, Hengerer B, Kostka M 2007. Different species of α-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J Neurosci 27: 9220–9232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Krebs SK, Wolff M, Birk G, Hengerer B 2009. Seeding induced by α-synuclein oligomers provides evidence for spreading of α-synuclein pathology. J Neurochem 111: 192–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Ruf WP, Putcha P, Joyner D, Hashimoto T, Glabe C, Hyman BT, McLean PJ 2011. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular α-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J 25: 326–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios F, Ruipérez V, López I, Villanueva J, Gutierrez LM, Davletov B 2010. α-Synuclein sequesters arachidonic acid to modulate SNARE-mediated exocytosis. EMBO Rep 11: 528–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Kholodilov N, Vila M, Trillat AC, Goodchild R, Larsen KE, Staal R, Tieu K, Schmitz Y, Yuan CA, et al. 2002. Resistance of α-synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 14524–14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ 2009. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 13010–13015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Spencer B, Coffee E, Patel P, Michael S, Patrick C, Adame A, Rockenstein E, Masliah E 2011. α-Synuclein sequesters Dnmt1 from the nucleus: A novel mechanism for epigenetic alterations in Lewy body diseases. J Biol Chem 286: 9031–9037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK 2008. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem 283: 9089–9100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Uchikado H, Fujishiro H, Tsuboi Y 2010. Evidence in favor of Braak staging of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 25 (Suppl 1): S78–S82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxakis E 2010. Post-transcriptional regulation of α-synuclein expression by mir-7 and mir-153. J Biol Chem 285: 12726–12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agnaf OM, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, Gibson MJ, Curran MD, Court JA, Mann DM, Ikeda S, et al. 2003. α-Synuclein implicated in Parkinson's disease is present in extracellular biological fluids, including human plasma. FASEB J 17: 1945–1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliezer P, Zweckstetter D, Masliah M, Lashuel EHA 2010. Phosphorylation at S87 is enhanced in synucleinopathies, inhibits α-synuclein oligomerization, and influences synuclein-membrane interactions. J Neurosci 30: 3184–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanoulidou E, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K 2010a. Specific cell-derived soluble α-synuclein oligomers are degraded by the 26S proteasome and impair its function. Neurobiol Aging 31: 953–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Melachroinou K, Roumeliotis T, Garbis SD, Ntzouni M, Margaritis LH, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K 2010b. Cell-produced α-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. J Neurosci 30: 6838–6851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidiou E, Elenis D, Papasilekas T, Stranjalis G, Gerozissis K, Ioannou P, Vekrellis K 2011. In vivo assessment of α-synuclein secretion. PLoS One 6: e22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelender S, Kaminsky Z, Guo X, Sharp AH, Amaravi RK, Kleiderlein JJ, Margolis RL, Troncoso JC, Lanahan AA, Worley PF, et al. 1999. Synphilin-1 associates with α-synuclein and promotes the formation of cytosolic inclusions. Nat Genet 22: 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito A, Dohm CP, Kermer P, Bähr M, Wouters FS 2007. α-Synuclein and its disease-related mutants interact differentially with the microtubule protein tau and associate with the actin cytoskeleton. Neurobiol Dis 26: 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW 2000. A Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Nature 404: 394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin DL, Nemani VM, Voglmaier SM, Anthony MD, Ryan TA, Edwards RH 2005. Neural activity controls the synaptic accumulation of α-synuclein. J Neurosci 25: 10913–10921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenburg RA, Rospigliosi C, Meray RK, Kessler JC, Lashuel HA, Eliezer D, Lansbury PT Jr 2007. The impact of the E46K mutation on the properties of α-synuclein in its monomeric and oligomeric states. Biochemistry 46: 7107–7118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J, Nilsson C, Kachergus J, Munz M, Larsson EM, Schüle B, Langston JW, Middleton FA, Ross OA, Hulihan M, et al. 2007. Phenotypic variation in a large Swedish pedigree due to SNCA duplication and triplication. Neurology 68: 916–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J, Tichopad A, Golub Y, Munz M, Schweitzer KJ, Wolf B, Berg D, Mueller JC, Gasser T 2008. Genetic variability in the SNCA gene influences α-synuclein levels in the blood and brain. FASEB J 22: 1327–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Sugama S, Sekiyama K, Sekigawa A, Tsukui T, Nakai M, Waragai M, Takenouchi T, Takamatsu Y, Wei J, et al. 2010. .A β-synuclein mutation linked to dementia produces neurodegeneration when expressed in mouse brain. Nat Commun 1: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, Shen J, Takio K, Iwatsubo T 2002. α-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol 4: 160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE, Uryu K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ 1999. Axon pathology in Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia hippocampus contains α-, β-, and γ-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 13450–13455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Kotzbauer PT, Uryu K, Leight S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM 2008. Neuroinflammation and oxidation/nitration of α-synuclein linked to dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 28: 7687–7698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reitböck P, Anichtchik O, Bellucci A, Iovino M, Ballini C, Fineberg E, Ghetti B, Della Corte L, Spano P, Tofaris GK, et al. 2010. SNARE protein redistribution and synaptic failure in a transgenic mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Brain 133 (Pt 7): 2032–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JM 2002. The synucleins. Genome Biol 3: REVIEWS3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JM, Jin H, Woods WS, Clayton DF 1995. Characterization of a novel protein regulated during the critical period for song learning in the zebra finch. Neuron 15: 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Duda JE, Murray IV, Chen Q, Souza JM, Hurtig HI, Ischiropoulos H, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM 2000. Oxidative damage linked to neurodegeneration by selective α-synuclein nitration in synucleinopathy lesions. Science 290: 985–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM 2003. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of τ and α-synuclein. Science 300: 636–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Bevis BJ, Shorter J, Strathearn KE, Hamamichi S, Su LJ, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Rochet JC, McCaffery JM, et al. 2008. The Parkinson's disease protein α-synuclein disrupts cellular Rab homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goers J, Manning-Bog AB, McCormack AL, Millett IS, Doniach S, Di Monte DA, Uversky VN, Fink AL 2003. Nuclear localization of α-synuclein and its interaction with histones. Biochemistry 42: 8465–8471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk OS, Li S, Sullivan LF, Chen W, Kondrikova G, Manfredsson FP, Mandel RJ, Muzyczka N 2008. The phosphorylation state of Ser-129 in human α-synuclein determines neurodegeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 763–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk OS, Li S, Nash K, Gorbatyuk M, Lewin AS, Sullivan LF, Mandel RJ, Chen W, Meyers C, Manfredsson FP, et al. 2010. In vivo RNAi-mediated α-synuclein silencing induces nigrostriatal degeneration. Mol Ther 18: 1450–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosavi N, Lee HJ, Lee JS, Patel S, Lee SJ 2002. Golgi fragmentation occurs in the cells with prefibrillar α-synuclein aggregates and precedes the formation of fibrillar inclusion. J Biol Chem 277: 48984–48992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründemann J, Schlaudraff F, Haeckel O, Liss B 2008. Elevated α-synuclein mRNA levels in individual UV-laser-microdissected dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Nucleic Acids Res 36: e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty T, Credle J, Rodriguez O, Wills J, Oaks AW, Masliah E, Sidhu A 2011. Hyperphosphorylated τ in an α-synuclein-overexpressing transgenic model of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci 33: 1598–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C, Angot E, Bergström AL, Steiner JA, Pieri L, Paul G, Outeiro TF, Melki R, Kallunki P, Fog K, et al. 2011. α-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells. J Clin Invest 121: 715–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Mallory M, Masliah E 2001. β-Synuclein inhibits α-synuclein aggregation: A possible role as an anti-parkinsonian factor. Neuron 32: 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi NT, Parker A, Dallas ML, Pennington K, Hung CC, Pearson HA, Boyle JP, Robinson P, Peers C 2009. α-Synuclein modulation of Ca2+ signaling in human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells. J Neurochem 111: 1192–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodara R, Norris EH, Giasson BI, Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Lynch DR, Lee VM, Ischiropoulos H 2004. Functional consequences of α-synuclein tyrosine nitration: Diminished binding to lipid vesicles and increased fibril formation. J Biol Chem 279: 47746–47753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Shi M, Chung KA, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Galasko D, Jankovic J, Zabetian CP, Leverenz JB, Baird G, et al. 2010. DJ-1 and α-synuclein in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers of Parkinson's disease. Brain 133 (Pt 3): 713–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu LJ, Sagara Y, Arroyo A, Rockenstein E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Wong J, Takenouchi T, Hashimoto M, Masliah E 2000. α-Synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. Am J Pathol 157: 401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis KJ, Chereau D, Brigham EF, Chiou SS, Schöbel S, Frigon NL, Yu M, Caccavello RJ, Nelson S, Motter R, et al. 2009. Polo-like kinase 2 (PLK2) phosphorylates α-synuclein at serine 129 in central nervous system. J Biol Chem 284: 2598–2602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PH, Hager H, Nielsen MS, Hojrup P, Gliemann J, Jakes R 1999. α-Synuclein binds to τ and stimulates the protein kinase A-catalyzed τphosphorylation of serine residues 262 and 356. J Biol Chem 274: 25481–25489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Kanthasamy A, Ghosh A, Yang Y, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG 2011. α-Synuclein negatively regulates protein kinase Cδ expression to suppress apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons by reducing p300 histone acetyltransferase activity. J Neurosci 31: 2035–2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowaed A, Schmitt I, Kaut O, Wüllner U 2010. Methylation regulates α-synuclein expression and is decreased in Parkinson's disease patients’ brains. J Neurosci 30: 6355–6359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junn E, Lee KW, Jeong BS, Chan TW, Im JY, Mouradian MM 2009. Repression of α-synuclein expression and toxicity by microRNA-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 13052–13057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle PJ 2008. α-Synucleinopathy models and human neuropathology: Similarities and differences. Acta Neuropathol 115: 87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp F, Exner N, Lutz AK, Wender N, Hegermann J, Brunner B, Nuscher B, Bartels T, Giese A, Beyer K, et al. 2010. Inhibition of mitochondrial fusion by α-synuclein is rescued by PINK1, Parkin and DJ-1. EMBO J 29: 3571–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinar DP, Balija MB, Kügler S, Opazo F, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Wender N, Kim HY, Taschenberger G, Falkenburger BH, Heise H, et al. 2009. Pre-fibrillar α-synuclein variants with impaired β-structure increase neurotoxicity in Parkinson's disease models. EMBO J 28: 3256–3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga K, Tokutake T, Ishikawa A, Uchiyama T, Tokuda T, Onodera O, Nishizawa M, Ikeuchi T 2010. Differential levels of α-synuclein, β-amyloid42 and tau in CSF between patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81: 608–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodilov NG, Neystat M, Oo TF, Lo SE, Larsen KE, Sulzer D, Burke RE 1999. Increased expression of rat synuclein in the substantia nigra pars compacta identified by mRNA differential display in a model of developmental target injury. J Neurochem 73: 2586–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TD, Paik SR, Yang CH 2002. Structural and functional implications of C-terminal regions of α-synuclein. Biochemistry 41: 13782–13790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Burger C, Lundberg C, Johansen TE, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Bjorklund A 2002. Parkinson-like neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of α-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. J Neurosci 22: 2780–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klegeris A, Pelech S, Giasson BI, Maguire J, Zhang H, McGeer EG, McGeer PL 2008. α-Synuclein activates stress signaling protein kinases in THP-1 cells and microglia. Neurobiol Aging 29: 739–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucken J, Shin Y, Masliah E, Hyman BT, McLean PJ 2004. Hsp70 reduces α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. J Biol Chem 279: 25497–25502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]