Background: Reg-1α is a small secretory protein overexpressed during the early stages of Alzheimer disease.

Results: Secreted Reg-1α stimulates axon outgrowth, and this paracrine effect is mediated by its receptor EXTL3.

Conclusion: Reg-1α emerges as an important actor in brain plasticity and the regenerative process.

Significance: Learning how Reg-1α regulates the nerve cells is important for understanding its implications in early stages of Alzheimer disease.

Keywords: Cell Differentiation, Immunochemistry, Neurobiology, Rat, siRNA, EXTL3, Reg-1α, Biochemistry, Cell Culture, Cellular Biology

Abstract

Regenerating islet-derived 1α (Reg-1α)/lithostathine, a member of a family of secreted proteins containing a C-type lectin domain, is expressed in various organs and plays a role in proliferation, differentiation, inflammation, and carcinogenesis of cells of the digestive system. We previously reported that Reg-1α is overexpressed during the very early stages of Alzheimer disease, and Reg-1α deposits were detected in the brain of patients with Alzheimer disease. However, the physiological function of Reg-1α in neural cells remains unknown. Here, we show that Reg-1α is expressed in neuronal cell lines (PC12 and Neuro-2a) and in rat primary hippocampal neurons (E17.5). Reg-1α is mainly localized around the nucleus and at the membrane of cell bodies and neurites. Transient overexpression of Reg-1α or addition of recombinant Reg-1α significantly increases the number of cells with longer neurites by stimulating neurite outgrowth. These effects are abolished upon down-regulation of Reg-1α by siRNA and following inhibition of secreted Reg-1α by antibodies. Moreover, Reg-1α colocalizes with exostosin tumor-like 3 (EXTL3), its putative receptor, at the membrane of these cells. Overexpression of EXTL3 increases the effect of recombinant Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth, and Reg-1α is not effective when EXTL3 overexpression is down-regulated by shRNA. Our findings indicate that Reg-1α regulates neurite outgrowth and suggest that this effect is mediated by its receptor EXTL3.

Introduction

Regenerating islet-derived 1α (Reg-1α)2/pancreatic thread protein/lithostathine (1) is a small secreted protein that is part of a large family (2). It was first described as being secreted in pancreatic juice where it may control the growth of calcium carbonate crystals (3–5). Reg-1α is expressed in various organs, is specifically involved in the proliferation and differentiation of cells in the digestive system, and can act as a paracrine/autocrine factor (6, 7). However, it is not known whether Reg-1α can be secreted by nerve cells, although Reg2, another member of the family, is released by sensory and motor neurons and can act on neighboring cells (8, 9).

Kobayashi et al. (10) isolated a Reg receptor, EXTL3, which mediates the Reg growth signal for β-cell regeneration. EXTL3 is thought to belong to the exostosin tumor (EXT) family because it shows homology with the C-terminal regions of EXT2 and EXT1. The N-terminal region of EXTL3, which has no homology with any other member, contains the membrane-spanning domain and the Reg binding domain. Although the large majority of studies have been carried out in pancreatic cells, de la Monte et al. (11) showed that Reg-1α is also expressed in the central nervous system and that its expression is developmentally regulated as it is strongly detected in fetal and infant brain and very low in normal adult brain. They also suggested that in mature brain Reg-1α could be associated with neuronal sprouting and regeneration (11, 12). Moreover, the expression of the Reg receptor in brain is also developmentally regulated and contributes to brain development (13).

We have already shown that Reg-1α is overexpressed during the very early stages of Alzheimer disease (AD), and deposits of this protein have been observed in the brain of AD patients (14). Moreover, in AD, elevated Reg-1α expression may reflect widespread aberrant neuritic sprouting correlated with synaptic disconnection and dementia (11, 15, 16). Recently, we have demonstrated that Reg-1α and its receptor EXTL3 are expressed in the cortical layer and hippocampal formation of Microcebus murinus brain and that Reg-1α expression increases in aged and AD-like animals (17). Interestingly, Reg-1α is highly susceptible to self-proteolysis and generates a C-terminal polypeptide that is largely insoluble at physiological pH and readily polymerizes into fibrils (18–20).

Thus, as the precise localization and function of Reg-1α and its capacity to be secreted in the central nervous system have not yet been determined, we examined the expression, localization, and function of Reg-1α in the neuronal cell lines PC12 and Neuro-2a (N2a) as well as in primary hippocampal cells. Here, we show that Reg-1α is preferentially localized at the membrane and around the nucleus of neuronal cells. In addition, Reg-1α is secreted, and it positively regulates neurite outgrowth through its membrane receptor EXTL3. We thus propose that Reg-1α is a new neuronal secreted factor that acts at least in part through its receptor EXTL3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

PC12 Cells

The rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). PC12 cells were routinely grown in DMEM with 2 mm glutamine, 10% horse serum, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) in tissue culture dishes and passaged once a week. For differentiation in nerve growth factor (NGF)-containing medium, cells were seeded in 35-mm dishes or in 6-well plates coated with a thin film of collagen type I from rat tail tendons (Sigma) dissolved in 0.5 m acetic acid, precipitated in an equal volume of ethanol, and dried by evaporation. Before adding the differentiation culture medium (DMEM with 4 mm glutamine and 0.5% FBS), dishes were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). PC12 cells were seeded in this low serum medium at a density of ∼100,000 cells/cm2, and 50 ng/ml NGF (Promega) was added before incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in humidified air. To evaluate the effect of Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth, purified human recombinant Reg-1α (Biovendor, Germany) was added simultaneously at a concentration of 10−7 m.

Neuro-2a Cells

Murine N2a cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in culture medium (Opti-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS) in a humidified incubator under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. To study neurite outgrowth, cells were seeded at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2 in 35-mm dishes or in 6-well plates coated with a thin film of poly-d-lysine (Sigma), and 10−7 m Reg-1α was added for 48 h.

Primary Hippocampal Neuronal Cells

Primary cell cultures of neurons were obtained by dissecting the hippocampus of Sprague-Dawley rat embryos at E17.5 (C. E. Depré, Saint Doulchard, France). Cells were dissociated by enzymatic incubation in trypsin and 0.05% EDTA and by repeated pipetting. Cells were resuspended in Neurobasal medium with 2% B27, 0.25% 200 mm glutamine, 1% Glutamax, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 on glass coverslips in 24-well plates previously coated with 10 μg/ml poly-d-lysine, and purified human recombinant Reg-1α at a dose of 10−7 m was simultaneously added (in some experiments). Cells were then cultured at 37 °C for 48 h (2 days in vitro) in humidified air with 5% of CO2.

Plasmid and Transfections

Full-length human Reg-1α cDNA in pCMV6-XL5 (GenBankTM accession number NM_002909.3; OriGene Technologies) was subcloned into the peGFP-C3 vector (Clontech) to produce a fusion protein in which the C-terminal end of Reg-1α is fused with the green fluorescence protein (GFP). Full-length mouse Reg-1α cDNA (GenBank accession number BC028761; Open Biosystems) was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Clontech). The full-length human Reg-1α cDNA in pCMV6-XL5 was used as a template to produce by PCR amplification the mutant Reg-1α form without the 22 amino acids of the peptide signal (PS) (human Reg-1α ΔPS). Primers were 5′-GGGTCGACACCATGCAAGAGGCCCAGACA-3′ and 5′-GGGGATCCTAGTTTTTGAACTTGCAGAC-3′ (start and stop codons are shown in italics) with the SalI and BamHI sites (underlined) inserted to facilitate cloning. The construct was subcloned in the pIRES2-eGFP vector (Clontech). Empty peGFP-C3, pcDNA3.1, and pIRES2-eGFP vectors were used as negative controls.

2 × 106 PC12 cells were transfected using NucleofectorTM (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). Cells were spun down at 900 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in 100 μl of Nucleofector solution V (Amaxa Biosystems) at room temperature followed by addition of 2 μg of each construct or empty vector. Mixtures were transferred to a 2-mm electroporation cuvette (Amaxa Biosystems) and inserted in the Nucleofector, and program U-29 was used for transfection. Immediately after transfection, 500 μl of culture medium was added to each cuvette, and transfected cells were plated in collagen-coated 35-mm dishes or 6-well plates with 1 ml of culture medium/well. Cells were grown for 48 h and then used for Western blot or immunocytochemical analysis. N2a cells were transfected with the same constructs/vectors using 6 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Freshly dissociated primary hippocampal cells were transfected using Nucleofector following the same protocol used for PC12 cells but with program G13. Transfected cells were then seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates coated with poly-d-lysine to study neurite differentiation or in 6-well plates to validate the transfection by Western blot analysis.

To inhibit Reg-1α expression, we used two different siRNAs that target the following rodents Reg-1α sequences: 5′-GGA GCA GUG GGU CUC UGU UTT-3′ (siRNA1) and 5′-GGU CUC UGU UUC UCU ACA ATT-3′ (siRNA2). Both sense and antisense strands were synthesized by Invitrogen in desalted form. Transfection of siRNAs was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, for each transfection, 500 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen), 6 μl of Lipofectamine 2000, and 500 pmol of siRNAs per well were used.

Full-length human EXTL3 cDNA was subcloned into the pIRES2-eGFP vector (a gift from Dr. Win van Hul). The shRNA against human EXTL3 and scrambled, non-effective shRNA (negative control) were cloned in pGFP-V-RS (TG313126, OriGene Technologies). PC12 cells were transfected with these constructs using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transfected cells were grown for 48 h and then used for Western blot or immunocytochemical analysis. For Reg-1α antibody blocking experiments, PC12 and primary neurons were plated as above, and rabbit anti-Reg-1α antibody was added to the culture medium when the medium was changed, respectively, to differentiation culture medium for PC12 and to Neurobasal with B27 supplement for primary neurons. Neurite outgrowth was then analyzed.

Neurite Outgrowth Measurement

Neurite outgrowth was quantified by imaging neurons using a Zeiss Axiovert microscope and an MRm2 camera system. Images of five fields per well were taken. Neurite growth was determined by manually tracing the length of 1) all the neurites that could be associated with a particular cell body and 2) the longest neurite per cell for all cells in a field that had an identifiable neurite and for which the entire neurite arbor could be visualized. We measured the number, length, and total output (sum length) of only primary neurites. In the hippocampal primary cultures, the longest neurites analyzed are Tau-positive and Map2-negative axons. Neuronal processes were analyzed using Axiovision LE 4.4 software and NeuronJ software (distributed as a plug-in for ImageJ). For each graph, data on neurite length were generated from at least three independent experiments, and more than 100 cells were counted for each experiment except in the case of the siRNA experiments where 50 cells were counted per experiment. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance and post hoc Student's t test.

Subcellular Fractionation and Immunoblotting

For cell fractionation into cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, PC12 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT) with Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) and E64, a cysteine protease inhibitor (1:1000; Sigma). Cells were allowed to swell on ice for 15 min and then homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. The integrity of nuclei was verified under a light microscope, and the homogenate was layered on 40% sucrose. Nuclei were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min to collect the nuclei (pellet). Supernatants were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min to separate the cytosol (supernatant) and membrane (pellet) fractions. The protein concentration was determined with the BCA assay (Pierce). 20 mg of the cytosolic and of the membrane fractions were loaded for 12.5% SDS-PAGE. For total cellular protein extracts, cells were scraped in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton, 1 mm EGTA) with Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The protein concentration was determined with the BCA assay (Pierce), and 20 mg of proteins were loaded for 12.5% SDS-PAGE. To determine whether Reg-1α is secreted by neural cells, we freeze-dried the culture medium before analysis to concentrate proteins.

For Western blot analysis, SDS-PAGE gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.22 μm; Bio-Rad) by standard electroblotting. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h, and immunolabeling was revealed by chemiluminescence reaction using the ECL Western blot detection reagents. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-Reg-1α (1:500) (18), rabbit anti-GFP (TP401, Cliniscience), and mouse anti-β-actin (A54-41, Sigma-Aldrich). The anti-Reg-1α polyclonal antibody was produced in rabbits, and its specificity has already been assessed (19). Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgGs (1:2000; Interchim).

Immunocytochemistry and Microscopy

PC12 cells were grown and induced to differentiate on glass coverslips coated with rat tail collagen. N2a cells and hippocampal neurons were grown on glass coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine. Cells were fixed in formaldehyde/PBS for 20 min followed by three washes in PBS. Cells were blocked and permeabilized in PBS supplemented with 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton and then incubated at 4 °C with primary antibodies rabbit anti-Reg-1α, goat anti-EXTL3 (R&D Systems), mouse anti-β3-tubulin (Sigma), and sheep anti-TGN38 (AbD Serotec) in the same buffer overnight. Secondary antibodies directed against rabbit or goat IgGs were conjugated, respectively, to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) and Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). For epifluorescence imaging, cells were viewed with Leica and Zeiss microscopes, and images were captured with a camera using the Metamorph and Axiovision software programs. For confocal imaging, cells were observed with a Leica TCS4D confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, CA).

RESULTS

Reg-1α Is Expressed in Neuronal Cells

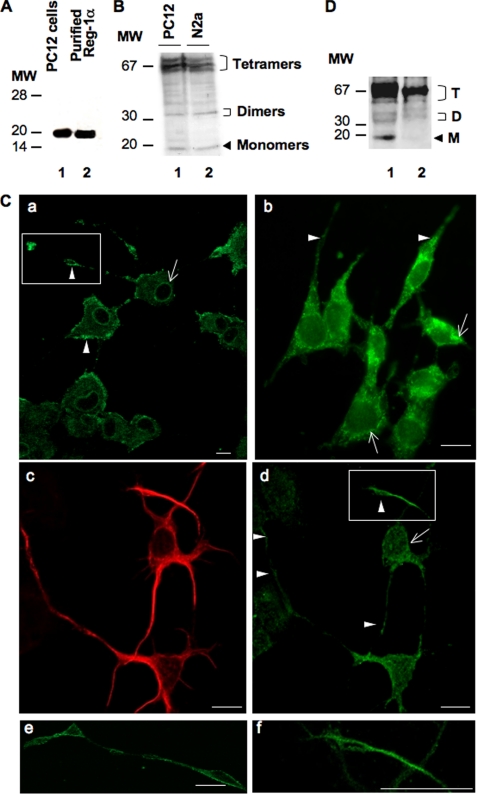

To investigate the function of Reg-1α in neural cells, we first assessed Reg-1α expression in rat PC12 cells, which acquire a neuron-like phenotype upon NGF stimulation, and in mouse N2a cells, a neural crest-derived cell line that has been extensively used to study neuronal differentiation and axonal growth. In these cells, Reg-1α had an apparent molecular mass of 18–20 kDa (Fig. 1A, lane 1), similar to that of purified human recombinant Reg-1α (Fig. 1A, lane 2). Although the theoretical molecular mass of Reg-1α is estimated to be 16 kDa, it is known that in SDS-PAGE gels its apparent molecular mass ranges from 16 to 22 kDa due to the presence of O-linked glycans (21). Moreover, as described previously (19), Reg-1α formed dimers (apparent molecular mass, ∼35 kDa) and tetramers (apparent molecular mass, ∼70 kDa) that remained visible also under denaturing electrophoresis conditions (12.5% SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence studies in PC12 (Fig. 1C, panels a and e), in N2a cells (Fig. 1C, panel b), and in hippocampal neurons at 2 days in vitro (Fig. 1C, panels c, d, and f) revealed that Reg-1α was mainly localized along the plasma membrane and slightly in the cytosol. Expression was stronger in the perinuclear region (Fig. 1C, panels a, b, and d, arrows) and in neurite membranes, particularly in growth cones (Fig. 1C, panels a, b, and d, arrowheads; panels e and f are higher magnifications of the insets in a and d). Subcellular fractionation confirmed that Reg-1α was mainly localized in the membrane fraction (Fig. 1D, lane 1) with a smaller portion in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 1D, lane 2). The specificity of the polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody was assessed previously (17, 19), and it does not cross-react with other members of the family or with neuronal thread protein (11).

FIGURE 1.

Reg-1α is expressed in PC12 and N2a cells as well as in embryonic hippocampal neurons (E17.5; 2 days in vitro). A, total cell protein extracts (20 μg) from differentiated PC12 cells grown in the presence of 50 ng/ml NGF for 48 h were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed using a rabbit polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated on the left. Lane 1, Reg-1α in PC12 cells has an apparent molecular mass of ∼20 kDa; lane 2, the specificity of the anti-Reg-1α antibody was tested using purified human recombinant Reg-1α, which shows an apparent molecular mass of 18 kDa. B, PC12 (lane 1) and N2a (lane 2) cell extracts were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis using the rabbit polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody shows three clusters of Reg-1α expression with molecular masses of ∼70, 35, and 20 kDa (tetramers, dimers, and monomers of Reg-1α). Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated on the left. C, immunofluorescence analysis in differentiated PC12 (panels a and e), N2a (panel b) cells, and hippocampal neurons (panels c, d, and f), which express β3-tubulin (panel c), show that Reg-1α is mainly localized at the plasma membrane (panels a, b, and d, arrowheads), particularly in growth cones (panels e and f; higher magnifications of the insets in panels a and d) and in the perinuclear region (panels a, b, and d, arrows). Images were visualized by confocal microscopy (Z-projections of three confocal optical sections; intervals, 0.6 μm). Scale bars, 10 μm. D, immunoblot analysis of membrane (lane 1) and cytoplasm (lane 2) fractions from differentiated PC12 cells using the polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody. Tetramers (T), dimers (D), and monomers (M) of Reg-1α are indicated. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated on the left.

Reg-1α Increases Number of Cells with Longer Neurites by Stimulating Neurite Outgrowth

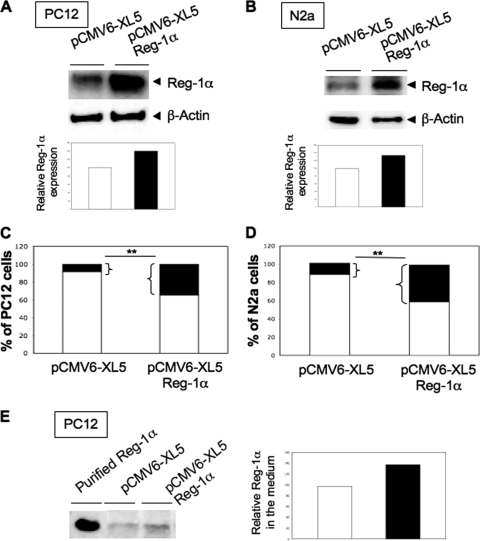

To investigate the potential effects of Reg-1α on neuronal growth, we transiently transfected PC12 and N2a cells with human full-length Reg-1α and then investigated the effects of Reg-1α overexpression. These cells are considered to be differentiated when neurite length is twice that of the cell body. Reg-1α expression was increased by 40% in PC12 (Fig. 2A) and by 35% in N2a (Fig. 2B) cells without modification of β-actin expression when compared with controls (cells transfected with empty pCMV6-XL5 vector). Reg-1α overexpression significantly increased the number of cells with neurites longer than two cell diameters (about 4-fold) (Fig. 2, C and D, black rectangles) as well as the total neurite length and longest neurite length per cell without modification of the number of neurites per cell (Table 1). Transfection of empty vector or of transfection reagent alone (Amaxa and Lipofectamine) did not have any effect. As Reg-1α is described as a secreted protein in the digestive tract, we then verified whether Reg-1α was secreted by neuronal cells. Our data show (Fig. 2E) that this is the case and that Reg-1α secretion is increased upon transfection, suggesting that Reg-1α could act as an extracellular factor.

FIGURE 2.

Overexpression of Reg-1α increases number of PC12 and N2a cells considered as differentiated and secretion of Reg-1α. Total cell protein extracts obtained from PC12 (A) and N2a (B) cells transfected with control empty vector (pCMV6-XL5) or with Reg-1α (pCMV6-XL5-Reg-1α) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using the polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. Histograms (A and B) show the quantification of Reg-1α relative expression. Quantification of the percentage of undifferentiated (white) and differentiated (i.e. when neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (black) PC12 (C) and N2a (D) cells shows an increase in the number of cells considered as differentiated upon overexpression of Reg-1α but not of empty pCMV6-XL5 vector. Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls based on Student's t test analysis (**, p < 0.01). E, 20 mg of proteins from freeze-dried culture medium from PC12 cells transfected with control empty vector (pCMV6-XL5) or with Reg-1α (pCMV6-XL5-Reg-1α) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using the polyclonal anti-Reg-1α antibody. Histograms show the quantification of Reg-1α relative expression.

TABLE 1.

Effects of Reg-1α overexpression on neurite outgrowth in PC12 and N2a cells

Total neurite length per cell, longest neurite length, and number of neurites per cell were measured and are expressed as mean ± S.E.

| Transfection reagent | pCMV6-XL5 | pCMV6-XL5-Reg-1α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC12 cells | |||

| Total neurite length per cell (μm) | 33.5 ± 3 | 30.5 ± 3 | 38.5 ± 1.8a |

| Longest neurite length per cell (μm) | 47.8 ± 5.6 | 45.9 ± 5 | 62.1 ± 4a |

| Neurites per cell | 1.8 ± 0.18 | 1.7 ± 0.19 | 2 ± 0.12 |

| N2a cells | |||

| Total neurite length per cell (μm) | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 22.9 ± 2.5 | 39.5 ± 3.2a |

| Longest neurite length per cell (μm) | 21.1 ± 1.3 | 21.6 ± 1.6 | 30.7 ± 1.8a |

| Neurites per cell | 1.04 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.08 |

a Indicates significant differences from controls (Student's t test, p < 0.05).

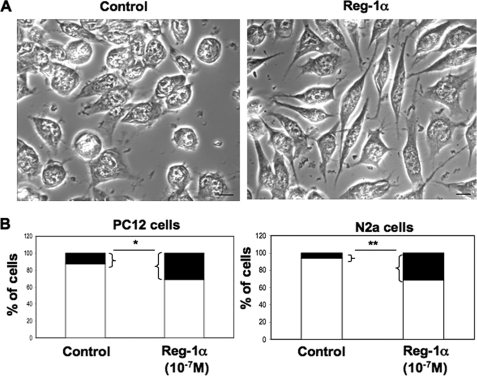

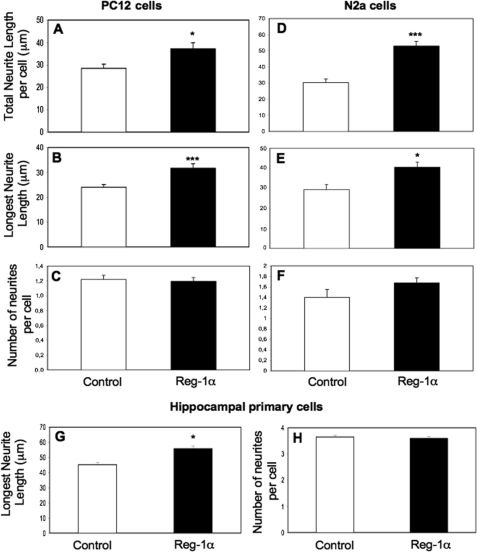

To test this hypothesis, we incubated PC12, N2a, and primary hippocampal cells with 10−7 m human recombinant Reg-1α for 48 h and assessed its effect on neurite elongation. The concentration used was chosen based on studies in pancreatic cell lines by Kobayashi et al. (10) and on personal data (data not shown). The duration of treatment corresponded to the time needed to observe neurite outgrowth in NGF-treated PC12 cells and in N2a cells grown on poly-d-lysine. As with overexpression of Reg-1α, addition of Reg-1α clearly increased the number of cells with longer neurites (Fig. 3A for N2a cells). Quantitative analysis of the effects of recombinant Reg-1α (Fig. 3B) showed a 2- and 6-fold increase in the percentage of PC12 (left panel) and N2a (right panel) cells with longer neurites in comparison with untreated controls. To describe in detail the positive effect of Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth, the total neurite length, length of the longest neurite, and number of neurites per cell were quantified in PC12 (Fig. 4, A–C) and N2a (Fig. 4, D–F) cells. In primary hippocampal neurons, we measured specifically the length of the longest neurite, which represents the axon in this experimental condition, and the number of neurites per cell (Fig. 4, G and H). Both the total neurite length per cell and the length of the longest neurite were increased in Reg-1α-treated cells in comparison with untreated cells (Fig. 4, A, B, D, E, and G). Conversely, recombinant Reg-1α did not modify the number of neurites per cell relative to control, untreated cells (Fig. 4, C, F, and H).

FIGURE 3.

Human recombinant Reg-1α increases number of PC12 and N2a cells with longer neurites. A, phase-contrast images of N2a cells in culture. Note the increase of neurite length 48 h after addition of 10−7 m Reg-1α in the medium (right panel) compared with untreated, control cells (left panel). Scale bars, 10 μm. B, quantification of the percentage of undifferentiated (white) and differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (black) PC12 and N2a cells. Treatment with 10−7 m recombinant Reg-1α increases the number of cells with longer neurites (black) in comparison with untreated controls. Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls based on the Student's t test analysis (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 4.

Recombinant Reg-1α increases outgrowth of PC12 and N2a cells as well as of rat embryonic hippocampal neurons. Total neurite length per cell (A and D), length of the longest neurite (B, E, and G), and number of neurites (C, F, and H) per cell were measured and are expressed as mean ± S.E. Recombinant Reg-1α (10−7 m) significantly increases the total neurite length (A and D) and longest neurite length (B, E, and G) but does not influence the number of neurites per cell (C, F, and H). Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls based on the Student's t test analysis (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). White, control cells; black, Reg-1α-treated cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Down-regulation of Reg-1α Expression Decreases Number of Cells Considered as Differentiated

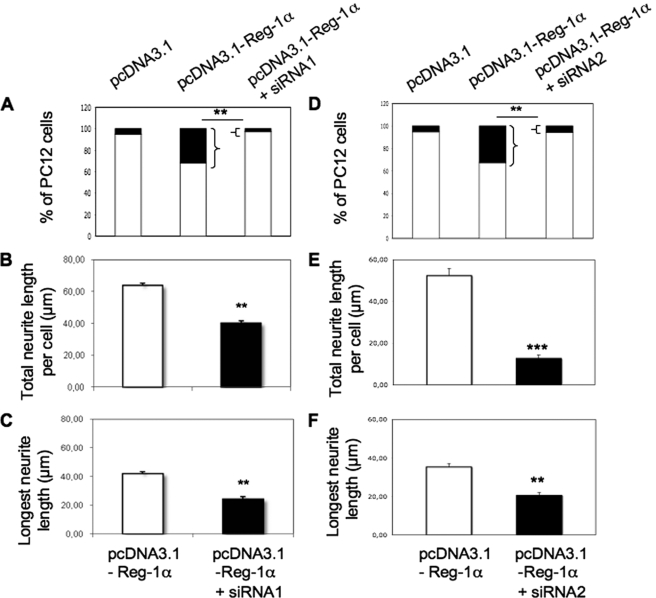

To confirm the specificity of the effects of Reg-1α, we down-regulated Reg-1α in PC12 cells by using two siRNA duplexes (siRNA1 and siRNA2). The two duplexes used induced a decrease of Reg-1α content. As illustrated in PC12 cells co-transfected with siRNA2 and pcDNA3.1-Reg-1α (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B), Reg-1α expression was decreased by 40 and 60% in comparison with cells that were transfected, respectively, with control pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-Reg-1α alone. Co-transfection of Reg-1α and siRNA1 (Fig. 5, A–C) or siRNA2 (Fig. 5, D–F) decreased the number of cells with longer neurites by 80% (Fig. 5, A and D, black rectangles) as well as the total neurite length (by 40% with siRNA1 and 75% with siRNA2; Fig. 5, B and E) and longest neurite length (by 40% for siRNA1 and siRNA2; Fig. 5, C and F). As the duplex siRNA2 was slightly more effective, it was used to down-regulate the expression of endogenous Reg-1α. Silencing of endogenous Reg-1α, which was confirmed in hippocampal neurons by Western blot analysis (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D), significantly decreased the number of differentiated cells (Table 2). Moreover, in hippocampal neurons, siRNA2 induced a significant decrease of the longest neurite length when compared with control cells (siRNA2, 52 ± 2.7 μm; control, 62.8 ± 4 μm; *, p < 0.05) without modification of the number of neurites per cell (siRNA2, 3.7 ± 0.08; control, 3.6 ± 0.1).

FIGURE 5.

Down-regulation of overexpressed Reg-1α by siRNAs reduces neurite outgrowth in NGF-treated PC12 cells. Transfection of the two anti-Reg-1α siRNA duplexes (siRNA1, A–C; and siRNA2, D–F) decreased the percentage of cells considered as differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (A and D, black rectangles), the total neurite length (B and E), and the longest neurite length (C and F) per cell. Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls (pcDNA3.1-Reg-1α) based on the Student's t test analysis (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

TABLE 2.

Silencing of endogenous Reg-1α by siRNA decreases number of PC12 and N2a cells considered as differentiated

Quantification of the percentage of undifferentiated and differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) PC12 and N2a cells after down-regulation of endogenous Reg-1α by siRNA2. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.

| PC12 cells |

N2a cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | siRNA | Control | siRNA | |

| Undifferentiated cells (%) | 88 ± 4.5 | 95 ± 9 | 91 ± 4.5 | 95 ± 2.3 |

| Differentiated cells (%) | 12 ± 3.8 | 5 ± 2a | 9 ± 2.2 | 5 ± 1.2a |

a Indicates significant differences from control cells (Student's t test, p < 0.05).

Reg-1α Acts as Paracrine Factor on Neurite Outgrowth

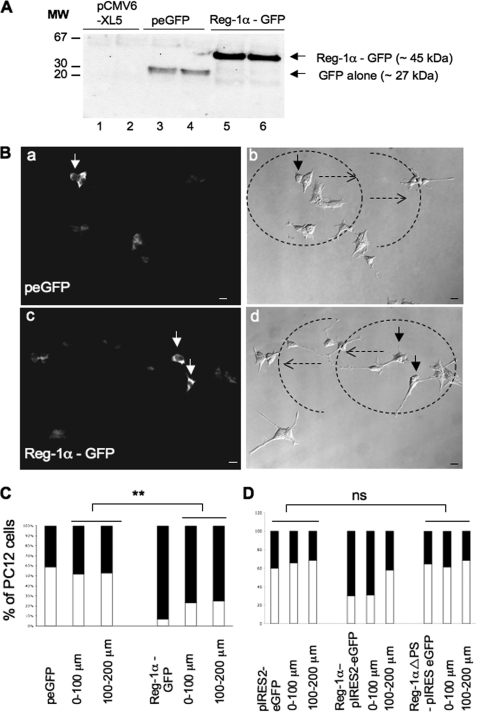

To identify the transfected cells and to determine whether Reg-1α could act as a paracrine factor, we transiently transfected hippocampal neurons and PC12 and N2a cells with C-terminal GFP-tagged Reg-1α or GFP alone. GFP-tagged Reg-1α was detected with an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 6A). As illustrated for the PC12 cell line, Reg-1α-GFP-positive cells displayed longer neurites than control cells (GFP alone) (Fig. 6B, arrows). Quantitative analysis of total neurite length, longest neurite length, and number of neurites per cell in GFP-positive cells confirmed that Reg-1α overexpression, but not GFP alone, specifically increased neurite length in neuronal cells (Table 3).

FIGURE 6.

Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis of PC12 cells that overexpress Reg-1α and of untransfected neighboring cells. A, PC12 cells were transfected with empty pCMV6-XL5 (lanes 1 and 2) or peGFP (lanes 3 and 4) vector or Reg-1α-GFP (lanes 5 and 6) (see “Materials and Methods”). Cell lysates were collected 48 h after transfection and immunoblotted with the anti-GFP antibody to determine the transfection efficacy. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated on the left. B, GFP immunostaining shows that PC12 cells that overexpress Reg-1α-GFP have longer neurites (panel c, arrows) than GFP-transfected cells (panel a, arrow). Panels b and d show the concentric circles around transfected cells (dotted arrows) every 100 μm (0–100 and 100–200 μm). Scale bars, 10 μm. C, quantification of the percentage of undifferentiated (white) and differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (black) cells shows an increase of the number of PC12 cells considered as differentiated when they overexpress Reg-1α-GFP and also of the number of their neighboring cells considered as differentiated in comparison with control, peGFP-transfected cells. Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls following Student's t test analysis (**, p < 0.01). D, quantification of the percentage of undifferentiated (white) and differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (black) cells shows that overexpression of the mutant Reg-1α ΔPS-pIRESeGFP, which lacks the signal peptide, has no effect on the differentiation of transfected PC12 cells and of neighboring cells. ns, no significant differences from controls (Student's t test).

TABLE 3.

Effects of GFP-tagged Reg-1α overexpression on neurite outgrowth in PC12 and N2a cells and hippocampal neurons

Total neurite length per cell, longest neurite length, and number of neurites per cell were measured and are expressed as mean ± S.E.

| PC12 cells |

N2a cells |

Hippocampal neurons |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peGFP | Reg1-α-GFP | peGFP | Reg1-α-GFP | peGFP | Reg1-α-GFP | |

| Total neurite length per cell (μm) | 74.9 ± 15 | 128.5 ± 18a | 27.6 ± 4 | 40.2 ± 3a | ||

| Longest neurite length per cell (μm) | 47.8 ± 4 | 69.5 ± 10a | 17.8 ± 1,6 | 26.8 ± 2b | 68 ± 6 | 90.2 ± 5a |

| Neurites per cell | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.08 |

a Indicates significant differences from control cells (Student's t test analysis, p < 0.05).

b Indicates significant differences from control cells (Student's t test analysis, p < 0.01).

To verify whether secreted Reg-1α could modify the number of cells with longer neurites also in neighboring untransfected cells, we drew concentric circles around transfected PC12 cells (0–100 and 100–200 μm) (Fig. 6B, panels b and d, dotted arrows) in which GFP-positive cells were not present and measured the percentage of PC12 cells considered as differentiated. The percentage of untransfected cells with longer neurites within the concentric circles around Reg-1α-GFP-transfected cells was higher than that of untransfected cells within the concentric circles around GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 6C). Moreover, when we overexpressed the human Reg-1α ΔPS-pIRES2-eGFP mutant, which lacks the signal peptide, the effect on neurite outgrowth of untransfected cells within the concentric circles around transfected cells was lost (Fig. 6D). Finally, quantitative analysis showed that Reg-1α-pIRES2-eGFP increased the total neurite length and longest neurite length of transfected and neighboring untransfected PC12 cells in comparison with control pIRES2-eGFP, whereas no effect was observed with the Reg-1α ΔPS-pIRES2-eGFP mutant (Table 4). To confirm the role of secreted Reg-1α in neurite elongation, we inhibited secreted Reg-1α with the anti-Reg-1α polyclonal antibody. We first determined that 10−6 m anti-Reg-1α antibody was the dose needed to efficiently inhibit neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (supplemental Table S1). At this concentration, the anti-Reg-1α polyclonal antibody blocked the effects of both physiologically secreted Reg-1α and recombinant Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth also in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 7). All these data demonstrate that secreted Reg-1α stimulates neurite elongation and acts as a paracrine factor.

TABLE 4.

Effects of Reg-1α-pIRES2-eGFP and Reg-1αΔPS-pIRES2-eGFP mutant overexpression on neurite outgrowth of transfected and neighboring, untransfected PC12 cells

Total neurite length per cell, longest neurite length, and number of neurites per cell were measured and are expressed as mean ± S.E.

| PC12 cells | pIRES2-eGFP | 0–100 μm | 100–200 μm | Reg-1α-pIRES2-eGFP | 0–100 μm | 100–200 μm | Reg-1αΔPSpIRES2-eGFP | 0–100 μm | 100–200 μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total neurite length per cell (μm) | 40 ± 4.5 | 38.9 ± 2 | 38.1 ± 4.4 | 57 ± 3.7a | 52.8 ± 3.1b | 37.8 ± 2.3 | 37.1 ± 2.6 | 35.7 ± 2.3 | 34 ± 3.1 |

| Longest neurite length per cell (μm) | 26.4 ± 1.5 | 26.1 ± 0.8 | 25.2 ± 2.3 | 38.5 ± 1.8a | 35.8 ± 1.6a | 27.1 ± 1.5 | 25 ± 1.1 | 25.1 ± 1.4 | 22.6 ± 1.5 |

| Neurites per cell | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.72 ± 0.08 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.73 ± 0.1 | 1.72 ± 0.1 |

a Indicates significant differences from control cells transfected with pIRES2-eGFP vector alone (Student's t test, p < 0.001).

b Indicates significant differences from control cells transfected with pIRES2-eGFP vector alone (Student's t test, p < 0.01).

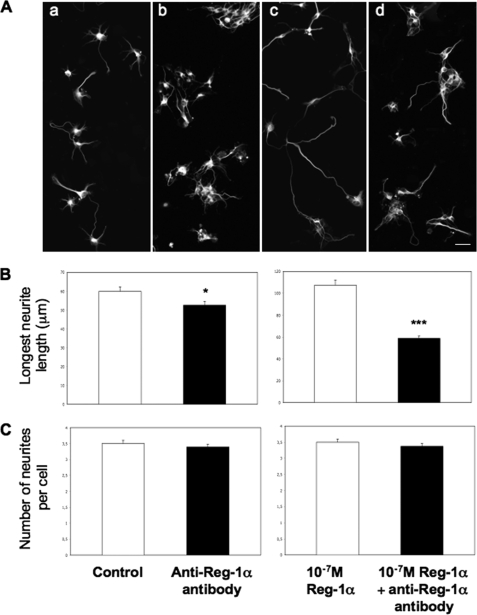

FIGURE 7.

Anti-Reg-1α polyclonal antibody blocks effects of secreted and recombinant Reg-1α on hippocampal neurite outgrowth. A, immunofluorescence analysis of hippocampal neurons stained by β3-tubulin shows that the anti-Reg-1α antibody (10−6 m) (panels b and d) hinders neurite elongation when compared with control cells (untreated) (panel a) and with cells incubated with 10−7 m recombinant Reg-1α (panel c). Scale bar, 10 μm. B and C, the anti-Reg-1α antibody (10−6 m) significantly decreases the effect of secreted (B, left panel) and recombinant (B, right panel) Reg-1α on the longest neurite length but does not influence the number of neurites per cell (C). Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student's t test; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). White, control cells (no antibody); black, Reg-1α antibody-treated cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

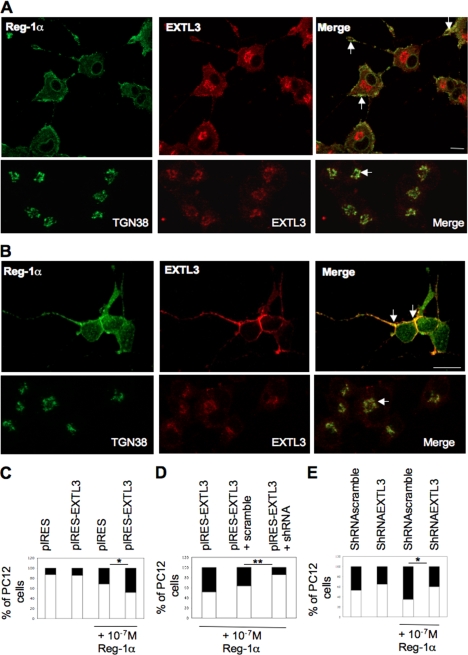

Reg-1α Stimulates Neurite Elongation through Its Membrane Receptor EXTL3

To determine whether secreted Reg-1α could act through its putative membrane receptor EXTL3, we first analyzed EXTL3 expression by immunofluorescence. EXTL3 was mainly localized in the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 8A, lower panels, arrow) but colocalized with Reg-1α at the plasma membrane in cell bodies and neurites of PC12 cells (Fig. 8A, upper panels, Merge, arrows) and of β3-tubulin-positive hippocampal neurons (Fig. 8B, upper panels, Merge, arrows).

FIGURE 8.

EXTL3 is expressed in PC12 cells and hippocampal neurons and mediates Reg-1α effect on neurite elongation. A and B, immunofluorescence analysis in PC12 cells considered as differentiated (A, upper panels) and hippocampal neurons (B, upper panels) shows that Reg-1α (green) colocalizes at the plasma membrane with EXTL3 (red) (Merge, arrows). EXTL3 (red) (A and B, lower panels) is also expressed in the Golgi apparatus and colocalizes with TGN38 (green), a specific marker of the Golgi apparatus (Merge, arrows). Images were visualized by confocal microscopy (Z-projections of three confocal optical sections; intervals, 0.6 μm). Scale bar, 10 μm. C, quantification shows that the increase in the percentage of cells with longer neurites (black rectangles) is significantly higher when recombinant Reg-1α is added to the medium of cells that overexpress EXTL3 (pIRES-EXTL3 + Reg-1α) rather than empty vector (pIRES + Reg-1α). Overexpression of EXTL3 alone (pIRES-EXTL3) does not modify the percentage of cells with longer neurites when compared with overexpression of empty vector (pIRES). D, quantitative analysis of undifferentiated (white) and differentiated (i.e. neurite length is twice that of the cell body) (black) PC12 cells shows that Reg-1α is less effective when EXTL3 is down-regulated (pIRES-EXTL3 + shRNA) as the percentage of cells considered as differentiated is significantly lower in these cells than in PC12 cells that overexpress EXTL3 (pIRES-EXTL3) or in cells co-transfected with EXTL3 and a control shRNA (pIRES-EXTL3 + scramble). Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student's t test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). E, quantification shows that the increase in the percentage of cells with longer neurites (black rectangles) is significantly lower when recombinant Reg-1α is added to the medium of cells when endogenous EXTL3 is down-regulated (shRNAEXTL3 + Reg-1α versus shRNAscramble + Reg-1α). Down-regulation of EXTL3 alone (shRNAEXTL3) induces a slight decrease of the percentage of cells with longer neurites when compared with transfection of a non-effective shRNA (shRNAscramble). Asterisks indicate significant differences (Student's t test; *, p < 0.05).

To investigate the involvement of the Reg-Reg receptor signaling system, we overexpressed EXTL3 in PC12 cells. Overexpression of EXTL3 alone (pIRES-EXTL3) did not modify the number of cells with longer neurites (Fig. 8C, black rectangles). However, addition of recombinant Reg-1α in such cultures increased by 2-fold the number of cells considered as differentiated only in EXTL3-overexpressing cells (Fig. 8C, pIRES-EXTL3 + Reg-1α and pIRES + Reg-1α, black rectangles), suggesting that the effects of Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth are mediated through its receptor.

To confirm the specificity of this effect, we then transiently transfected PC12 cells with pIRES-EXTL3 alone or together with anti-EXTL3 shRNA (pIRES-EXTL3 + shRNA) or scrambled shRNA (pIRES-EXTL3 + scramble) and incubated cells with 10−7 m human recombinant Reg-1α. Co-transfection of EXTL3 and shRNA (Fig. 8D) decreased significantly the number of cells with longer neurites (black rectangles) induced by Reg-1α. Moreover, down-regulation of endogenous EXTL3 by shRNA significantly decreased the percentage of cells with longer neurites induced by Reg-1α when compared with control non-effective shRNA (Fig. 8E). Specifically, EXTL3 silencing significantly decreased total neurite outgrowth (effective shRNA + Reg-1α, 21.7 ± 2.3 versus scrambled, ineffective shRNA + Reg-1α, 31.4 ± 2.3; **, p < 0.01; Student's t test analysis) without modifying the number of neurites per cell.

DISCUSSION

Reg-1α is involved in proliferation and differentiation of liver, pancreatic, gastric, and intestinal cells (6, 22) and has been associated with differentiation/dedifferentiation of pancreatic acinar cells without any effect on cell proliferation (23, 24). Here, we used primary embryonic hippocampal neurons (E17.5; 2 days in vitro) and two cell lines (PC12 cells, which are derived from a rat pheochromocytoma and reversibly respond to NGF by induction of the neuronal phenotype, and N2a, which are derived from a neuroblastoma and belong to a neural lineage) to investigate the expression, localization, and functions of Reg-1α in nerve cells. We first show that Reg-1α is expressed in neuronal cells with perinuclear localization and a particularly strong expression at the membrane of the cell bodies and along neurites as reported recently for neurons from M. murinus brain (17). We then demonstrate that neurite outgrowth is stimulated by Reg-1α overexpression or addition of recombinant Reg-1α, and it is reduced when Reg-1α is down-regulated by siRNA. Reg-1α increased the percentage of cells with longer neurites without affecting the mean number of neurites per cell and the number of primary neurite branching points as already demonstrated for Reg2, another member of this superfamily (supplemental Table S2). Therefore, we think that the effects of Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth might be restricted to the stimulation of elongation of small, pre-existing processes. Moreover, the results obtained in PC12 cells suggest that the effect on neurite elongation could probably be due to promotion of NGF-mediated differentiation as already demonstrated for other secreted proteins, such as the amyloid protein precursor (25). These data strongly suggest that Reg-1α stimulates differentiation only in cells that are already determined as neuronal cells.

We then show that Reg-1α, a member of a multifunctional family of secreted proteins, is a new neuronal secreted factor. Indeed, overexpression of Reg-1α increases the secretion of Reg-1α in the medium, and recombinant Reg-1α stimulates neurite length. Moreover, the effect of Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth was lost when a Reg-1α mutant deleted of the signal peptide that is required for the secretion of the protein was overexpressed. Similarly, addition of an anti-Reg-1α antibody to the medium abolished the effect of secreted Reg-1α on neurite outgrowth. These results indicate that Reg-1α acts as a paracrine factor on neuronal elongation as demonstrated previously for Reg2. Reg2 is a neurotrophic factor involved in the survival of motor and sensory neurons after axon damage. Similarly to Reg-1α, it presents a subcellular localization and acts on the same (autocrine) or on neighboring (paracrine) cells (8, 9).

The presence of specific membrane receptors for these secreted proteins is suggested because biological effects were observed after addition of purified Reg proteins to the culture medium or after systemic administration to animals (26). Kobayashi et al. (10) identified EXTL3 as the Reg-1α receptor involved in the regulation of pancreatic β-cells for maintaining the β-cell mass. However, EXTL3 is also expressed in other tissues, such as brain, suggesting the possible involvement of Reg-Reg receptor signaling in a variety of cell types other than pancreatic β-cells. In mouse embryos, EXTL3 mRNA is expressed in both the central and peripheral nervous system from E11.5 to E16.5, and its expression is developmentally regulated and contributes to brain development (13). In M. murinus, Reg-1α and its receptor EXTL3 are localized in the same pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus (17). Here, we show that Reg-1α co-localizes with EXTL3 at the cell membrane of neuronal cells, and we demonstrate that the effects of Reg-1α on neurite elongation are mediated at least in part through this receptor. We are now trying to identify other membrane Reg-1α receptors that may be involved in the effect of Reg-1α. Because EXTL3 is also involved in the biosynthesis of heparan sulfate, which mediates crucial steps during brain development, such as neurogenesis, neurite outgrowth, and axonal pathfinding (27), Reg-1α binding to EXTL3 could alter heparan sulfate maturation and consequently modulate adhesion to extracellular matrix factors and neurite outgrowth.

In conclusion, secreted Reg-1α emerges as an important actor in neurite elongation. The increase of Reg-1α at the very early stages of AD (14) and its lower expression in AD-like, aged mouse lemurs in comparison with healthy elderly animals (17) support the hypothesis of an early role of Reg-1α in brain plasticity and the regenerative process and suggest that Reg-1α and its receptor may be clinically important targets in neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Vicky Diakou from the University Montpellier 2 Imaging facility.

This work was supported by grants from Groupe de Recherche sur la Maladie d'Alzheimer.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables S1 and S2.

- Reg

- regenerating islet-derived

- EXTL3

- exostosin tumor-like 3

- EXT

- exostosin tumor

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- N2a

- Neuro-2a

- E

- embryonic day

- PS

- peptide signal.

REFERENCES

- 1. Watanabe T., Yonekura H., Terazono K., Yamamoto H., Okamoto H. (1990) Complete nucleotide sequence of human reg gene and its expression in normal and tumoral tissues. The reg protein, pancreatic stone protein, and pancreatic thread protein are one and the same product of the gene. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 7432–7439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laurine E., Manival X., Montgelard C., Bideau C., Bergé-Lefranc J. L., Erard M., Verdier J. M. (2005) PAP IB, a new member of the Reg gene family: cloning, expression, structural properties, and evolution by gene duplication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1727, 177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Caro A., Lohse J., Sarles H. (1979) Characterization of a protein isolated from pancreatic calculi of men suffering from chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 87, 1176–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bimmler D., Graf R., Scheele G. A., Frick T. W. (1997) Pancreatic stone protein (lithostathine), a physiologically relevant pancreatic calcium carbonate crystal inhibitor? J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3073–3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geider S., Baronnet A., Cerini C., Nitsche S., Astier J. P., Michel R., Boistelle R., Berland Y., Dagorn J. C., Verdier J. M. (1996) Pancreatic lithostathine as a calcite habit modifier. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 26302–26306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang Y. W., Ding L. S., Lai M. D. (2003) Reg gene family and human diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 9, 2635–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miyaoka Y., Kadowaki Y., Ishihara S., Ose T., Fukuhara H., Kazumori H., Takasawa S., Okamoto H., Chiba T., Kinoshita Y. (2004) Transgenic overexpression of Reg protein caused gastric cell proliferation and differentiation along parietal cell and chief cell lineages. Oncogene 23, 3572–3579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishimune H., Vasseur S., Wiese S., Birling M. C., Holtmann B., Sendtner M., Iovanna J. L., Henderson C. E. (2000) Reg-2 is a motoneuron neurotrophic factor and a signalling intermediate in the CNTF survival pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 906–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Averill S., Davis D. R., Shortland P. J., Priestley J. V., Hunt S. P. (2002) Dynamic pattern of reg-2 expression in rat sensory neurons after peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 22, 7493–7501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kobayashi S., Akiyama T., Nata K., Abe M., Tajima M., Shervani N. J., Unno M., Matsuno S., Sasaki H., Takasawa S., Okamoto H. (2000) Identification of a receptor for reg (regenerating gene) protein, a pancreatic β-cell regeneration factor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10723–10726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de la Monte S. M., Ozturk M., Wands J. R. (1990) Enhanced expression of an exocrine pancreatic protein in Alzheimer's disease and the developing human brain. J. Clin. Investig. 86, 1004–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu Y. Y., Bhavani K., Wands J. R., de la Monte S. M. (1995) Insulin-induced differentiation and modulation of neuronal thread protein expression in primitive neuroectodermal tumor cells is linked to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1. J. Mol. Neurosci. 6, 91–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Osman N. M., Naora H., Otani H. (2004) Glycosyltransferase encoding gene EXTL3 is differentially expressed in the developing and adult mouse cerebral cortex. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 151, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duplan L., Michel B., Boucraut J., Barthellémy S., Desplat-Jego S., Marin V., Gambarelli D., Bernard D., Berthézène P., Alescio-Lautier B., Verdier J. M. (2001) Lithostathine and pancreatitis-associated protein are involved in the very early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de la Monte S. M., Xu Y. Y., Wands J. R. (1996) Modulation of neuronal thread protein expression with neuritic sprouting: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 138, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hashimoto M., Masliah E. (2003) Cycles of aberrant synaptic sprouting and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurochem. Res. 28, 1743–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marchal S., Givalois L., Verdier J. M., Mestre-Frances N. (2011) Distribution of lithostathine in the mouse lemur brain with aging and Alzheimer's-like pathology. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 431.e15–431.e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laurine E., Grégoire C., Fändrich M., Engemann S., Marchal S., Thion L., Mohr M., Monsarrat B., Michel B., Dobson C. M., Wanker E., Erard M., Verdier J. M. (2003) Lithostathine quadruple-helical filaments form proteinase K-resistant deposits in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51770–51778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grégoire C., Marco S., Thimonier J., Duplan L., Laurine E., Chauvin J. P., Michel B., Peyrot V., Verdier J. M. (2001) Three-dimensional structure of the lithostathine protofibril, a protein involved in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 20, 3313–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cerini C., Peyrot V., Garnier C., Duplan L., Veesler S., Le Caer J. P., Bernard J. P., Bouteille H., Michel R., Vazi A., Dupuy P., Michel B., Berland Y., Verdier J. M. (1999) Biophysical characterization of lithostathine. Evidences for a polymeric structure at physiological pH and a proteolysis mechanism leading to the formation of fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22266–22274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Reggi M., Capon C., Gharib B., Wieruszeski J. M., Michel R., Fournet B. (1995) The glycan moiety of human pancreatic lithostathine. Structure characterization and possible pathophysiological implications. Eur. J. Biochem. 230, 503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinoshita Y., Ishihara S., Kadowaki Y., Fukui H., Chiba T. (2004) Reg protein is a unique growth factor of gastric mucosal cells. J. Gastroenterol. 39, 507–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanchez D., Gmyr V., Kerr-Conte J., Kloppel G., Zenilman M. E., Guy-Crotte O., Pattou F., Figarella C. (2004) Implication of Reg I in human pancreatic duct-like cells in vivo in the pathological pancreas and in vitro during exocrine dedifferentiation. Pancreas 29, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanchez D., Mueller C. M., Zenilman M. E. (2009) Pancreatic regenerating gene I and acinar cell differentiation: influence on cellular lineage. Pancreas 38, 572–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Milward E. A., Papadopoulos R., Fuller S. J., Moir R. D., Small D., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L. (1992) The amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer's disease is a mediator of the effects of nerve growth factor on neurite outgrowth. Neuron 9, 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iovanna J. L., Dagorn J. C. (2005) The multifunctional family of secreted proteins containing a C-type lectin-like domain linked to a short N-terminal peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1723, 8–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bandtlow C. E., Zimmermann D. R. (2000) Proteoglycans in the developing brain: new conceptual insights for old proteins. Physiol. Rev. 80, 1267–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.