Background: Up-regulation of Cep55 and inactivation of p53 occur in the majority of human cancers.

Results: Cep55 expression and stability is repressed via p53 as a result of down-regulation of Plk1 protein levels.

Conclusion: We show a hierarchic regulation of Cep55 protein levels through a p53-Plk1-Cep55 axis.

Significance: These results provide clues for elucidation of the mechanisms of p53-mediated repression of cell cycle-related proteins.

Keywords: Cancer Biology, Cell Cycle, Molecular Cell Biology, p53, Protein Turnover, Cep55, Plk1

Abstract

Centrosomal protein 55 (Cep55), which is localized to the centrosome in interphase cells and recruited to the midbody during cytokinesis, is a regulator required for the completion of cell abscission. Up-regulation of Cep55 and inactivation of p53 occur in the majority of human cancers, raising the possibility of a link between these two genes. In this study we evaluated the role of p53 in Cep55 regulation. We demonstrated that Cep55 expression levels are well correlated with cancer cell growth rate and that p53 is able to negatively regulate Cep55 protein and promoter activity. Down-regulation of expression of Cep55 was accompanied by repression of polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) levels due to p53 induction. Overexpression of Plk1 and knockdown of p53 expression both enhanced the post-translational protein stability of Cep55. BI 2356, a selective Plk1 inhibitor, however, prevented Cep55 accumulation in p53 knockdown cells while persistently keeping Plk1 levels elevated. Our results, therefore, indicate the existence of a p53-Plk1-Cep55 axis in which p53 negatively regulates expression of Cep55, through Plk1 which, in turn, is a positive regulator of Cep55 protein stability.

Introduction

Using bioinformatics approaches to screen for genes involved in mitosis, over the past few years several groups have independently identified a novel coiled-coil protein, centrosomal protein 55 kDa (Cep55)2 (1–7). Cep55, also named FLJ10540 or C10orf3, localizes to the centrosome in interphase cells and is recruited to the midbody during cytokinesis and is essential for completion of cell abscission. Cep55 is a 464-amino acid protein containing 3 central coiled-coil domains encoded by a gene located on chromosome 10q23.33. Cylin-dependent kinase 1, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2, and subsequently Plk1 cooperate in the phosphorylation of Cep55 during mitosis (3). As a key component of the cellular machinery that mediates abscission, Cep55 together with tumor susceptibility gene 101 (Tsg 101) and Alix regulate membrane fission and fusion events near the midbody ring in the last stage of cell division (7–9). Dysregulated expression of Cep55, either depletion or overexpression, causes cytokinesis defects and an increase in the number of multinucleated cells. Notably, Cep55 has been found highly expressed in certain human tumors (10–14) and various tumor cell lines (15). Overexpression of Cep55 in mammalian cells is able to enhance cell migration and invasion (14). In addition, Cep55 shares certain characteristics with oncogenes such as anchorage-independent growth, enhanced cell growth at low serum levels, and induction of tumorigenesis in nude mice (10). Furthermore, suppression of Cep55 expression significantly retards the growth of cancer cells, which is associated with increased apoptosis (12). These findings suggest that aberrant expression of Cep55 could contribute to tumorigenesis.

p53 is a major tumor suppressor that is altered by point mutations in 50% of human cancers (16, 17). Among them, 95% of mutations are detectable within the central regions encoding the DNA binding domain of p53, and thereby mutant p53 lacks sequence-specific transactivation ability (18). Expression of mutant p53 is not the equivalent of p53 loss, and mutant p53s can acquire functions to drive cell migration, invasion, and metastasis (19). Under normal conditions, p53 is expressed at an extremely low level. Upon DNA damage, p53 is induced to accumulate in the cell nucleus through post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and acetylation (20–22). p53 plays an important role in mediating response to stress such as that induced by genotoxic damage and hypoxia resulting in either cell cycle arrest, which allows cells to repair DNA damage, or apoptosis, which eliminates cells with severely damaged DNA (23). p53 elicits its normal functions mainly by acting as a transcription factor, and it regulates genes contributing to the cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis. As a tumor suppressor, p53 executes its activity mainly via the positive transcription regulation of its target genes, such as Puma (24) or p21 (25), resulting in either apoptosis or growth arrest. In addition, p53 negatively regulates a number of transcription factors, such as c-Myc (26) or Forkhead Box M1 (FOXM1) (27), or other genes such as Plk1 (28, 29) by various mechanisms. Loss of p53 function is well known to influence cell cycle checkpoint controls. In this report we investigated the relationship between Cep55 and p53. We demonstrated that Cep55 expression is repressed via p53 as a result of down-regulation of Plk1 protein levels, which in turn compromises Cep55 protein stability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Plasmids, and Transfection

Human cervical cancer cell line HeLa, human ovarian cancer cell lines TOV112D, BR, TOV21G, ES1, SKOV3, MDAH2774, and BG1, human osteosarcoma cell line U2OS, human prostate cancer cell line PC3, and human lung cancer cell line H1299 of passages 10–30 were maintained in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen), 2 mm glutamine, and 200 units/ml each of streptomycin and penicillin G. Cells were passed with 0.1% trypsin and 0.04% EDTA in Hanks' medium. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. The wild-type (pC53-SN3) and the mutant human p53 plasmids (p53-A138V, R175H, R248W, R249S, R273H, V143A) were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). pRc/CMV-myc-Plk1 was provided by Dr. Kum Kum Khanna (30). The expression constructs for p53 siRNA (pSuper-p53) and control (pSuper) were provided by Dr. R. Agami (The Netherlands Cancer Institute). Plk1 targeting shRNA plasmids (9045, 9046, 9047) were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD). Transfection was performed at about 70% confluence with FuGENE 6 (Promega), Metafectene (Biontex, Munich, Germany), Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), or electroporation according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Growth Rate Assay

1 × 105 cells per well were seeded on six-well plates in the presence of 10% FBS-DMEM/F-12 in triplicate for 3 days. Individual wells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA every day, the number of cells was counted with a hemocytometer, and their viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Data from individual growth curves were used to calculate the doubling time using the algorithm (Roth V. 2006) provided by Doubling Time.

UV Irradiation

For UV irradiation, exponentially growing cells on culture dishes were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and then irradiated with lids removed in a Spectrolinker XL-1000 UV Crosslinker (Spectronics Corp., Westbury, NY) at energies of 50 and 100 J/m2. Fresh culture medium was added to the dishes immediately after irradiation.

Luciferase and β-Galactosidase Assays

Cells were grown in complete medium and replated at 3 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate 16–24 h before transfection. For the reporter gene assay, cells were transfected by Metafectene or Lipofectamine 2000 using 1.8 μg of mouse Cep55 promoter fragment containing sequences −4395 to −2761 or −2367 to −289 (relative to translation start site) fused to a luciferase reporter, the indicated amounts of expression plasmids, and 0.2 μg of pCMV-β-galactosidase expression vector for normalization of transfection efficiency. After transfection (20 h), cell extracts were prepared, and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined using Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System and the β-Galactosidase Enzyme Assay System (Promega). All assays were performed at least three times in duplicate.

Cell Treatment and Western Blot Analysis

To induce p53 activity, actinomycin D (ActD, Sigma) was added to cells for 8 h. To inhibit Plk1 activity in p53 knockdown cells, immediately after transfection of pSuper-p53 plasmid, cells were treated with BI 2536 (3 nm) (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) or co-transfected with Plk1 targeting shRNA plasmids and harvested at 72 h. To further confirm that Plk is required for the maintenance of Cep55 stability, proteasome inhibitor MG132 (5 μm) (Sigma) was included in the assays where Plk1 is knockdown. For protein half-life determination, cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) (Sigma) was added, and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Cells were scraped, and lysates were prepared in 100 μl of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (Bionovas Biotechnology, Toronto, Canada) with a protease inhibitor mixture (Bionovas Biotechnology) and a HaltTM phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Where indicated, cell lysates were treated with λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 30 min at 30 °C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Samples were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer (Bionovas Biotechnology) before electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred from the gel to a nitrocellulose paper that was blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in PBS followed by washing in PBS. Primary antibody incubations, including mouse anti-Cep55 11A5 (15), mouse anti-p53 (1:8,000, Sigma), mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10,000, Sigma), mouse anti-β-actin (1:8,000, Sigma), and rabbit anti-Plk1 (1:6,000, GeneTex, Irvine, CA) were carried out for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washing in PBS, the paper was incubated for 1 h with HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:4000, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:8000, Millipore, Billerica, MA). The peroxidase-labeled blots were developed with an ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences). Protein bands were digitalized using an imaging analyzer (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems) and quantified by Gel Capture (Version 3).

RESULTS

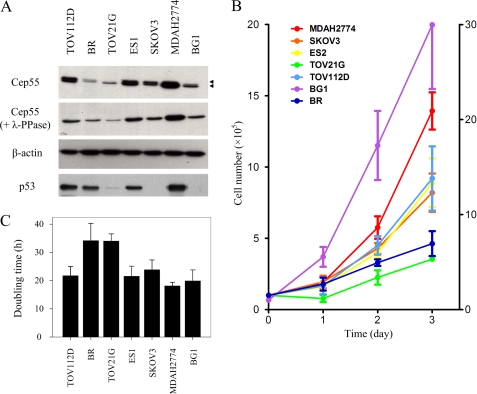

Correlation of Cep55 Protein Expression Levels and Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth

Cep55, as reported previously (4), is highly expressed in certain human tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma (10), breast cancer (11), colon cancer (12), lung cancer (14), and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (31). In this study we compared the expression levels of endogenous Cep55 in seven human ovarian cancer cell lines (TOV112D, BR, TOV21G, ES1, SKOV3, MDAH2774, and BG1) as detected by Western blot (Fig. 1A, upper panel). By means of a monoclonal antibody 11A5, which recognizes the NH2 terminus of human Cep55 (15), a doublet band of about 55 kDa was found in lysates of asynchronous ovarian cancer cells (arrowheads). Cep55 proteins were highly or moderately expressed in all cell lines tested with the exception of BR and TOV21G cells. Cell lysates were incubated with λ-phosphatase before immunoblotting to determine the phosphorylation states of Cep55 (Fig. 1A, middle panel). The slower migrating bands of Cep55 corresponded to the hyperphosphorylation forms, because treatment of cell lysates with λ-phosphatase resulted in a downshift of these bands. To determine whether Cep55 expression correlated with cell proliferation, the ovarian cell lines were cultured at identical initial cell numbers (1 × 105/well), and their growth was tracked by counting cell numbers at various time points over 72 h (Fig. 1B). Cells expressing lower levels of Cep55 (BR, TOV21G) consistently exhibited reduced cell growth at each time point analyzed. Similarly, cells expressing lower levels of Cep55 exhibited a delay of at least 10 h in doubling time as compared with other cells that highly or moderately expressed Cep55 (Fig. 1C). Taken together these results suggest that Cep55 is not merely a cell cycle-related protein, but its amount might reflect the status of cell proliferation.

FIGURE 1.

Cep55 expression contributes to cell proliferation. A, shown is an immunoblot analysis of human ovarian tumor cell lines expressing Cep55 using mAb 11A5 with (middle panel) or without (uppermost panel) λ-phosphatase (λ-PPase) treatment. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Arrowheads indicate double bands corresponding to phosphorylation modification of Cep55. Lysates were also probed with antibody to p53 in the Western blot analysis (lowest panel). B, growth curves of ovarian cell lines (1 × 105) cultured for 1–3 days are shown. Cells were harvested at different time points and then counted using a hemocytometer. The line graph shows cell numbers (105) against time in days. Note that the y axis/cell number of BG1 is on the right side of the graph. The results are shown as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, doubling time analyses are calculated based on cell numbers from growth curve shown in B using the logarithmic least squares fitting technique from Doubling Time. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

Cep55 Expression Is Negatively Regulated by p53

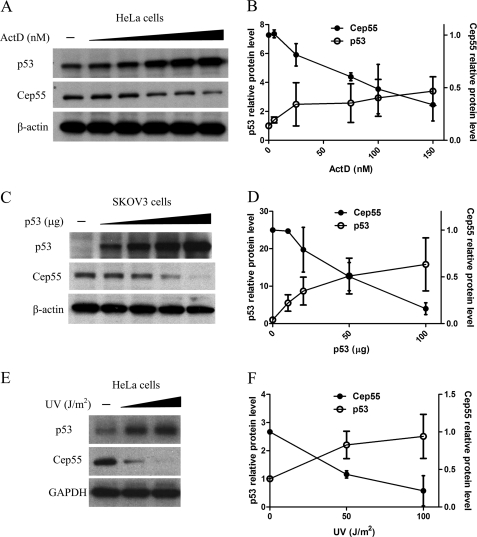

Tumor suppressor p53 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by acting as a transcription factor to regulate numerous genes. Given that various types of genotoxic stress induce the accumulation of p53 (23), we next investigated whether Cep55 expression is related to p53 induction using HeLa (wild-type p53) cells in which the expression of p53 is inducible by ActD or ultraviolet (UV). Cells were lysed after incubation for 8 h with various concentrations of ActD (0–150 nm), and the amounts of Cep55 and p53 proteins were determined by Western blot analyses (Fig. 2A). As expected, the abundance of p53 protein increased with increasing ActD doses (Fig. 2A, top). In contrast, treatment of HeLa cells with ActD resulted in a decrease in the levels of Cep55 starting from a concentration of 25 nm (Fig. 2A, middle). Densitometric analysis indicated that the level of Cep55 protein after ActD treatment (solid circle, Fig. 2B) in the HeLa cell line decreased to <35% of the original amounts in cells without treatment. We next examined the Cep55 protein levels in the response to UV. Exponentially growing HeLa cells were subjected to 0, 50, and 100 J/m2 of UV irradiation and were harvested at 12 h later. Western blot analysis revealed that Cep55 protein expression was repressed in the response to p53 induction (Fig. 2E). At a dose of 50 and 100 J/m2, the p53 protein levels were increased with increasing radiation doses, whereas the Cep55 levels decreased to 43 and 22% of control, respectively (solid circle, Fig. 2F). We further used SKOV3 (p53 null) cells in which the expression of p53 is inducible by transient transfection of wild-type p53 (pC53-SN3) plasmid (Fig. 2C). p53 was not detectable in SKOV3 cells (Fig. 2C, top), but the abundance of p53 protein increased significantly upon transfection of wild-type p53 plasmid. In contrast, the abundance of Cep55 protein decreased dose-dependently upon transfection of wild-type p53 plasmid (Fig. 2C, middle) to <20% that of the original amounts in cells without p53 transfection (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Repression of Cep55 protein expression in response to p53 induction. A, HeLa cells (wild-type p53) were treated with different concentrations of ActD (amounts are indicated on the x axis in B) for 8 h. C, SKOV3 cells (null p53) were transiently transfected with wild-type p53 expression vector pC53-SN3 (p53, amounts are indicated in the x axis in D) by electroporation. E, HeLa cells were irradiated with UV and harvested at 12 h after irradiation (UV energy, amounts are indicated in the x axis in F). Cell lysates were harvested, and proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and blotted for p53 and Cep55. β-Actin was used as the loading control. The relative level of each protein was quantified and is presented in the respective line graphs (B, D, and F). Note that the y axis/relative protein level of Cep55 is on the right side of the graph, whereas p53 relative protein level is on the left side of the same graph. Data are normalized to the β-actin densitometric value, and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

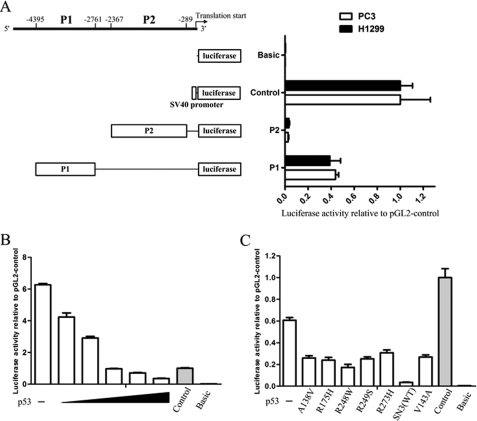

To elucidate the mechanism by which p53 negatively regulates Cep55 expression, we first generated two constructs (P1 and P2) harboring the 5′-flanking region of Cep55 gene and incorporated them into a luciferase reporter plasmid (Fig. 3A, left panel). The resulting vectors were then introduced into PC3 and H1299 cells by transient transfection together with pCMV-β-galactosidase (a control for normalization of transfection efficiency). The relative luciferase activities of the reporter constructs were then determined (Fig. 3A). The activity of the P1 construct, containing nucleotides −4395 to −2761 upstream of the Cep55 translational start codon, was much higher than that of the P2 construct, containing sequences downstream of P1 from −2367 to −289, in both cell types, suggesting the presence of a positive cis-regulatory element in the P1 region of Cep55 gene. To analyze the effects of p53 on Cep55 reporter activity, the P1 construct was then introduced into U2OS (Fig. 3B) and H1299 cells (Fig. 3C) together with an expression vector for wild-type p53 (SN3) or various p53 dominant negative mutants (A138V, R175H, R248W, R249S, R273H, V143A), in which a specific amino acid in the p53 DNA binding domain was mutated. In the presence of p53 expression, Cep55 reporter activity was dramatically suppressed in a dose-dependent manner in U2OS cells (Fig. 3B). A small reduction in reporter activity was seen with all dominant negative mutants of p53 in H1299 cells as compared with that with wild-type p53 (Fig. 3C), suggesting indirect regulation of Cep55 reporter activity via p53 DNA binding domains harboring the indicated amino acids. Alternatively, this result may be due to transcriptionally relevant interactions by parts of p53 mutants outside the inactivated DNA binding site.

FIGURE 3.

Cep55 promoter activity is suppressed by expression of p53. A, a schematic diagram of the luciferase reporter plasmids harboring various segments of Cep55 genomic sequences upstream of translation start site (left panel) is shown. The graph (right panel) represents the relative luciferase activity of the indicated constructs compared with the activity of the control vector (pGL2-control) in PC3 (open bars) and H1299 (solid bars) cells. Each assay was performed in triplicate, and the S.D. are indicated. B, shown is inhibition of the Cep55 promoter as a function of increasing p53 dosage. Increasing amounts of wild-type p53 (0.01, 0.02, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 μg) along with the Cep55-P1 reporter construct were transfected into U2OS cells and assayed for luciferase activity. Relative luciferase activity was determined as compared with that of a vector control (gray bar). C, partial attenuation of p53-suppressed Cep55 promoter activity by dominant-negative p53 DNA binding mutants (A138V, R175H, R248W, R249S, R273H, and V143A) in H1299 cells is shown. Cep55 promoter (P1) along with wild-type (SN3) or various p53 mutants (open bars) or control plasmids (pGL2-control, gray bar; pGL2-basic, solid bar) were transfected into H1299 cells and assayed for luciferase activity. Luciferase activities relative to control (pGL2-control) are shown.

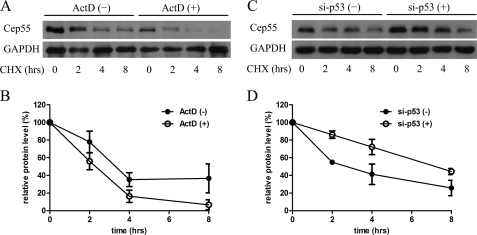

Stability of Cep55 Protein Is Influenced by p53

Because the p53 mutational analysis demonstrated that DNA binding by p53 was not necessarily required for Cep55 repression (Fig. 3), we postulated that Cep55 expression levels were possibly repressed by p53 at the post-translation level. We thus tested whether p53 regulates endogenous Cep55 protein stability using HeLa cells. First, we induced p53 by treating cells with ActD and determined Cep55 levels at several time points after the addition of cycloheximide (Fig. 4, A and B). Fig. 4A shows that Cep55 levels decreased faster in ActD-treated cells at every time point as compared with non-treated cells. Moreover, basal levels of Cep55 were lower in ActD-treated cells than the control. The Cep55 half-lives of ActD-treated and control cells were 1.9 and 4.8 h, respectively (Fig. 4B), indicating that decreased stability of Cep55 proteins plays a major role in reduced Cep55 expression levels via p53 induction. To confirm that p53 abundance is related to Cep55 protein stability, we reciprocally repressed p53 by transfection of cells with pSuper-based p53 shRNA (pSuper-p53) (Fig. 4C and 4D). Fig. 4C shows that Cep55 levels decreased more slowly in p53 knockdown cells at every time point than in cells that were transfected with control plasmid (pSuper). The Cep55 half-lives of p53 knockdown and control cells were 7 and 3.9 h, respectively (Fig. 4D), indicating that p53 abundance contributed to the stability of Cep55 proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Cep55 stability is influenced by p53. A, induction of p53 expression attenuates Cep55 protein stability. HeLa cells were treated with or without ActD for 8 h and then washed 3 times with PBS; cycloheximide (CHX) was then added for the indicated time points. Equalized amounts of cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of endogenous Cep55. B, shown is quantification of the expression in A. Cep55 levels are expressed as the percentages of the 0-h time point, and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, enhanced Cep55 protein stability in the absence of p53 expression is shown. HeLa cells were transfected with pSuper (control) or pSuper-p53 plasmids. Experiments were performed as in A and analyzed for expression of Cep55. D, shown is quantification of the expression in C. Cep55 levels are expressed as the percentages of the 0-h time point, and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

Repression of Cep55 by p53 Is through Plk1

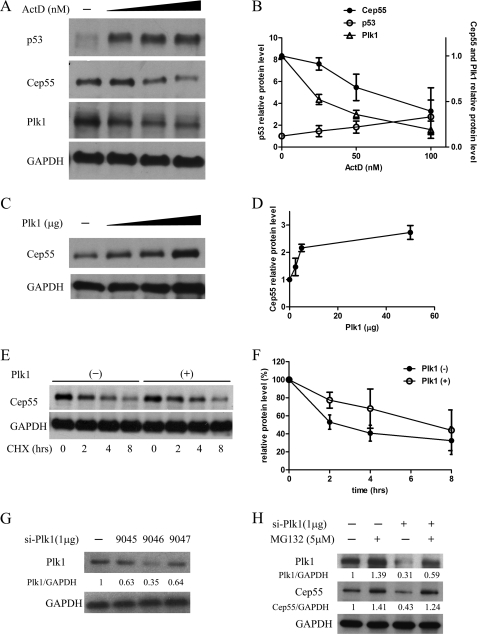

Plk1 is a direct transcription target of p53, and repression of Plk1 transcription by p53 induction has been shown in several studies (29, 32). As cells enter mitosis, cyclin-dependent kinase 1, ERK 2, and finally Plk1 are required for Cep55 phosphorylation on serines 425, 428, and 436 (3). To test the involvement of Plk1 in p53-mediated Cep55 repression, we assessed Plk1 expression in HeLa cells after ActD-induced DNA damage (Fig. 5, A and B). ActD induced an accumulation of endogenous p53 protein (Fig. 5A, top) and down-regulation of Cep55 (Fig. 5A, middle) as well as Plk1 (Fig. 5A, bottom). Plk1 repression started at a lower ActD concentration than Cep55 repression (Fig. 4B), suggesting Plk1 is more sensitive than Cep55 to p53 induction. We next overexpressed Plk1 to study its effect on Cep55 protein level (Fig. 5, C and D). Increasing amounts of Plk1 resulted in higher steady-state levels of wild-type Cep55 protein. To determine whether Cep55 is stabilized by Plk1, HeLa cells transfected with or without Plk1 plasmid were treated with cycloheximide 24 h after transfection to block further protein translation (Fig. 5, E and F). The decay rate of the existing pool of Cep55 protein was then determined by quantitation of Western blots of lysates from cells harvested at various time points after cycloheximide treatment. Cep55 had a half-life of 4.6 h in non-transfected cells, whereas the half-life of Cep55 increased to 6.9 h in the presence of Plk1 overexpression (Fig. 5F). To further confirm that Plk1 is required for the maintenance of Cep55 stability, we accordingly compared the accumulation of Cep55 in HeLa cells and HeLa cells with shRNA-mediated knockdown of Plk1 with or without proteasome inhibitor MG132 treatment. Different Plk1 shRNA plasmids knock down Plk1 expression to various extents, which was more evident with shRNA 9046 (Fig. 5G, top panel). A parallel immunoblot of the cell lysates revealed that the level of Cep55 protein was decreased in cells with si-Plk1 (Fig. 5H, third lane) as compared with mock-transfected cells (Fig. 5H, lane 1), whereas the Cep55 protein level was increased dramatically in mock-transfected cells (Fig. 5H, second lane) and si-Plk1 cells (Fig. 5H, fourth lane) after MG132 treatment. Our results, therefore, support a previous report that demonstrated Plk1-enhanced Cep55 stability in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (30).

FIGURE 5.

Plk1 regulates Cep55 expression and protein stability. A, p53 regulates Cep55 and Plk1 expression. HeLa cells were treated with different concentrations of ActD for 8 h after which cells were harvested. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for p53, Cep55, and Plk1. β-Actin was used as the loading control. The relative level of each protein was quantified and is represented in the line graph (B). Note that the y axis/relative protein level of Cep55 and Plk1 is on the right side of the graph, whereas the p53 relative level is on the left side of the same graph. Data were normalized to the β-actin densitometric value, and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, Cep55 expression levels increase as a function of Plk1 dosage. HeLa cells were transfected with the Plk1 expression vector by electroporation. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for Cep55. β-Actin was used as the loading control. Relative levels of protein were quantified and are represented in the line graph (D). E, Plk1 enhances Cep55 protein stability. HeLa cells were transfected with or without Plk1 plasmid followed by the addition of cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time points. Equalized amounts of cell lysates were analyzed for expression of endogenous Cep55. Relative levels of protein were quantified and are represented in the line graph (F). Cep55 levels are expressed as the percentages of the 0-h time point, and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. G, HeLa cells were either mock-transfected or transfected with the Plk1 shRNA plasmids. Seventy-two hours after transfection the cells were harvested, and the ability to knock down Plk1 was examined by Western blot using antibodies to Plk1. GAPAH was used as a loading control. H, HeLa cells were either mock-transfected or transfected with the Plk1 shRNA plasmids. Sixty-six hours after transfection the cells were treated with or without MG132 for another 6 h. The Cep55 and Plk1 protein levels were detected by immunoblotting of the lysates using antibody to Cep55 and Plk1. GAPDH was used as a control and results represented the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

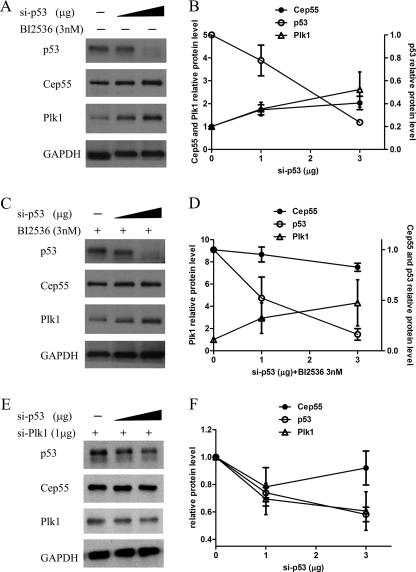

To determine whether Cep55 is repressed by p53 through Plk1, HeLa cells transfected with siRNA duplexes against p53 were left untreated or treated with BI 2536 (33–35), a small molecule inhibitor of Plk1, and the amount of Cep55 and Plk1 was determined by Western blots (Fig. 6). As expected, p53 was down-regulated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and C, top). After p53 knockdown for 72 h, Cep55 and Plk1 were up-regulated in cells without BI 2536 treatment (Fig. 6, A and B). In BI 2536-treated cells, although the amount of Plk1 persistently increased after p53 knockdown (Fig. 6, C and D), the Cep55 protein amount remained unchanged as compared with cells without p53 knockdown (Fig. 6, C and D). To exclude the “off-target” effects of Plk1 inhibitor BI2356, HeLa cells were double-transfected with pSuper p53 plasmid and Plk1 shRNA plasmid. Note the apparent decreased expression of both p53 and Plk1 levels, whereas Cep55 levels were merely slightly decreased or relatively constant in amount in the absence of p53 and Plk1 expression (Fig. 6, E and F), suggesting that Plk1 plays a mediatory role in p53-directed Cep55 expression. In summary, these results indicate that negative regulation of Cep55 expression by p53 was dependent on Plk1.

FIGURE 6.

p53-dependent Cep55 expression is mediated by Plk1 phosphorylation. HeLa cells transfected with pSuper p53 plasmid were left untreated (A) or treated with Plk1 inhibitor BI 2536 (C). In E, HeLa cells were co-transfected with pSuper p53 plasmid and Plk1 targeting shRNA plasmid. Cells were harvested after 72 h treatment, and cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for p53, Cep55, and Plk1. β-Actin was used as the loading control. The relative level of each protein was quantified and represented in the line graphs (B, D, and F), and results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Note the apparent increased expression of both Cep55 and Plk1 in the absence of p53 expression without BI 2536 treatment, whereas Cep55 levels remained unchanged, but Plk1 increased upon the addition of BI 2536 in the absence of p53 expression. Even in cells with p53 and Plk1 knockdown, Cep55 levels were slightly decreased or relatively constant in amount.

DISCUSSION

Cep55 plays an essential role in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and has been demonstrated in several studies to display dynamic cellular distribution patterns during cell-cycle progression (3–5). Cep55 localizes differentially to the centrosome during interphase and to the midbody during mitotic exit and cytokinesis (3–5). Cep55 protein levels are elevated in a wide range of human cancers, and its overexpression promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion; it is thus a factor that contributes to poor prognosis (10, 12, 14, 31). Suppression of Cep55 expression significantly retards the growth of cancer cells (10, 12). The results of this study demonstrate that the amount of Cep55 is well correlated with cell proliferation (Fig. 1) and that the elevated level of endogenous p53 and ectopically expressed p53 results in substantially lower levels of Cep55 protein and mRNA (Figs. 2 and 3). However, direct DNA binding of p53 to Cep55 promoter does not seem to be required for Cep55 transcriptional repression (Fig. 3), which is consistent with a negative identification of a p53 binding site on the Cep55 gene in an electronic search for transcription factor binding sites (SAbiosciences). We were thus interested in whether p53 takes part in the regulation of the level of Cep55 protein. Post-translational Cep55 stability, as measured by cycloheximide blocking method, was confirmed to be repressed by p53 (Fig. 4) but enhanced by Plk1 (Fig. 5). Blocking Plk1 enzyme activity resulted in Cep55 destabilization (Fig. 6). Therefore, overall our results suggest that repression of Cep55 expression by p53 is at least partially mediated by Plk1.

p53 becomes activated by DNA damage incurred from a variety of sources such as UV, γ-irradiation, or treatment with DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents. The primary DNA damage sensors include the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-related proteins ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia-related (ATR) (36, 37). p53 protein becomes stabilized upon phosphorylation by ATM/Chk2 or ATR/Chk1/casein-kinase 1 and accumulates in the nucleus (36–38). The role of p53 as a cellular gatekeeper of growth and division is mainly attributed to its ability to regulate a network of targets genes at the transcription level either as a transactivator or a repressor. p53 has been shown to repress many target genes involved in cell cycle control, thereby contributing to cell cycle arrest (39). These p53-repressed target genes are regulated either by direct interaction of p53 with target gene promoters or bound cofactors or by indirect interaction through regulation of other p53 target genes (39). Interestingly, our results suggest that p53-dependent repression of Cep55 is mediated indirectly through Plk1, which in turn regulates Cep55 protein stability. Several studies have demonstrated that p53 has a profound influence on Plk1 levels (28, 29, 32). After gamma irradiation, transcriptome analyses revealed consistent up-regulation of Plk1 as well as other genes controlling the G2/M transition in cells whose p53 genes were inactivated compared with those with wild-type p53 genes (28). Plk1 protein is repressed in response to 5-fluorouracil, and a reporter assay demonstrated that p53 can suppress the promoter activity of Plk1 (32). Recently, evidence has been presented to show that Plk1 is a direct transcription target of p53 independently of p21 and that p53 binds directly to the Plk1 promoter and inhibits Plk1 transcription (29).

The Plks are a group of highly conserved serine/threonine protein kinases that utilize ATP to add phosphate groups onto substrates, thereby potentially influencing the activity, stability, and/or subcellular localization of specific protein targets. Several lines of evidence have implicated Plk1 in the regulation of different processes, including mitotic entry, DNA damage checkpoint responses, spindle formation, and cytokinesis (40–43). In addition, Plk1 is overexpressed in a range of human tumors and correlates with a bad prognosis (44–46). By phosphorylating different substrates, Plk1 controls a number of processes throughout the cell cycles in vertebrate cells (42, 43, 47). Cep55 associates with and is phosphorylated by Plk1 during mitosis. HeLa cells ectopically expressing Plk1-dependent Cep55 phosphorylation mutant S436A exhibit cytokinesis failure, indicating that phosphorylation at SER-436 is absolutely required for the function of Cep55 during cytokinesis and that Cep55 and Plk1 proteins may cooperate to regulate the final stage of cell division (3). Mutation of the Plk1 phosphorylation site also lowers Cep55 stability by determining protein half-life with cycloheximide blocking, whereas overexpression of Plk1 increases Cep55 levels (30). Consistent with these data, we demonstrated that not only Cep55 expression levels but also its stability were enhanced by overexpression of Plk1 (Fig. 5, C and D and Fig. 5, E and F) and that the amount of Cep55 remained unchanged or slightly decreased in p53 knockdown cells after the addition of Plk1 inhibitor BI 2536 (Fig. 6, C and D), which competitively occupies the ATP binding pocket of Plk1 (34). However, recently Bastos et al. showed that Cep55 recruitment to the midbody is negatively regulated by Plk1 and that Cep55 can only target to the midbody once Plk1 is degraded (48). These data provide a potentially reverse correlation between Plk1 levels and Cep55 expression at the midbody during cytokinesis, but the investigators did not discuss whether Plk1 may influence the overall Cep55 protein stability in cells. Taken together, our findings suggest that tight regulation of Cep55 protein levels by p53 is mediated by Plk1 phosphorylation.

Although our data point out that Cep55 expression levels can be fine-tuned by Plk1 in a p53-dependent manner, the possibility that other molecules may participate in the p53 dependent-Cep55 repression pathway cannot be excluded. One example of such a candidate gene is oncogenic transcription factor Forkhead Box M1 (FOXM1), which is overexpressed in many human tumors and has a role in the cell cycle, DNA repair, and maintenance of genomic stability (49). There is evidence that p53 may repress FOXM1 transcription and protein expression (27) and that Cep55 is a downstream target of FOXM1 that binds directly to the Cep55 promoter (31). Interestingly, FOXM1, a substrate of Plk1, is bound and phosphorylated by Plk1 at G2/M. The Plk1-FOXM1 complex subsequently activates FOXM1 transcriptional activity, which is required for expression of key mitotic regulators, including Plk1 itself (50). This mode of regulation generates a positive-feedback loop between FOXM1 and Plk1 to ensure tight regulation of transcriptional networks essential for orderly mitotic progression (50).

Here we showed the existence of a p53-Plk1-Cep55 axis in which p53 negatively regulates expression of Plk1 and Plk1, in turn, is a positive regulator of Cep55 stability. However, in Fig. 1A, cells expressing lower levels of p53 (TOV21G, SKOV3, BG1) did not consistently exhibit higher levels of Cep55, whereas cells expressing higher levels of p53 (TOV112D, BR, ES1, MDAH2774) exhibited quite variable levels of Cep55. Thus, we could not find any correlation between Cep55 expression and p53 status in these cell lines. This phenomenon can probably be explained by the p53 mutation heterogeneity in cancers; p53 is altered by point mutations in ∼50% of human cancers and functionally inactivated in other 50% (51). Besides, in stable cell lines with null p53, a hierarchic regulation of Cep55 protein levels through a p53-Plk1-Cep55 axis seemed not to have existed, suggesting that a functional p53 expression level is a prerequisite for the existence of the p53-Plk1-Cep55 regulation axis (supplemental Fig. 1).

Because cytokinesis failure seems to be associated with tumorigenesis, basic knowledge about proteins that play roles in the regulation of cytokinesis may lead to the development of novel cancer therapeutics. Cep55, although up-regulated in many human cancers, is barely detectable in normal tissues except for testis and thymus (3, 4), making Cep55 a suitable target for cancer immunotherapy. Inoda et al. (11, 52) first isolated human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A24-restricted Cep55 peptides, which have been shown to be a target of cytotoxic T lymphocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HLA-A24 positive breast and colorectal carcinoma patients. Among all 11 designed peptides that displayed a HLA-A24 binding motif, only Cep55/c10orf3_193(10) peptide (VYVKGLLAKI) was highly immunogenic in breast carcinoma patients (11). However, not only Cep55/c10orf3_193(10) but also Cep55/c10orf3_402(11) (EFAITEPLVTF) and Cep55/c10orf3_283(12) (LYSQRRADVQHL) peptides were immunogenic in patients with colorectal cancer, suggesting that the antigenic peptide repertoire presented by HLA-A24 in colorectal carcinoma might be different from that in breast carcinoma (52). The same group also showed that cancer stem-like cells/tumor-initiating cells, resistant to chemotherapeutic agents such as irinotecan or etoposide, were as sensitive to cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific to tumor-associated antigen Cep55 as were non-cancer stem-like cells/tumor-initiating cell populations in colon cancer (53). Furthermore, adoptive transfer of Cep55/c10orf3_193(10)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone cells inhibited the tumor growth of SW480 SP cells in immunodeficient mice (53). These observations suggest a Cep55 peptide-based cancer vaccine therapy or adoptive cell transfer of the Cep55-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone is a possible approach for targeting chemotherapy-resistant colon cancer stem-like cells/tumor-initiating cells. In addition to Cep55, targeting Plk1 might be another promising approach for cancer therapy. About 80% of human tumors express high levels of Plk transcripts, but its mRNA is mostly absent in surrounding healthy tissues (54). Several Plk1 inhibitors (i.e. BI 2536, BI 6727, GSK461364, ON 019190.Na, and HMN-214) are in development and are undergoing evaluation as potential cancer treatments in clinical phase I/II trials (54–56). The hypothesis that stressed cancer cells without wild-type p53 alleles were highly sensitive to Plk1 inhibitors has been validated both in vivo and in vitro by Sur et al. (28).

In conclusion, we demonstrated a hierarchic regulation of Cep55 protein levels through a p53-Plk1-Cep55 axis in which a tight link between each component ensures proper cell cycle progression. Our data suggest that inactivation of p53 in human cancer cells leads to up-regulation of Cep55, thus underlining the importance of examining whether overexpression of Cep55 coincides with a high incidence of p53 mutations in human cancers. p53 was able to suppress Cep55 reporter activity, protein expression levels, and stability via repression of Plk1. These results contribute to our understanding of the relationship between p53 and Cep55 and provide clues for elucidation of the mechanisms and functional significance of p53-mediated repression of cell cycle-related proteins in general.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

pSuper, pSuper-p53, and Plk1 plasmids were kind gifts from Drs. Reuven Agami (The Netherlands Cancer Institute) and Kum Kum Khanna (Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Brisbane, QLD, Australia).

This study was supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Grant CMRPD170073, the Ministry of Education (Tope Center Grant EMRPD190481), and National Science Council, Taiwan Grant NSC-98-2320-B-182-019-MY3.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- Cep55

- centrosomal protein 55 kDa

- FOXM1

- Forkhead Box M1l

- Plk1

- polo-like kinase 1

- ActD

- actinomycin D.

REFERENCES

- 1. Doxsey S., McCollum D., Theurkauf W. (2005) Centrosomes in cellular regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 411–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doxsey S. J. (2005) Molecular links between centrosome and midbody. Mol. Cell 20, 170–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fabbro M., Zhou B. B., Takahashi M., Sarcevic B., Lal P., Graham M. E., Gabrielli B. G., Robinson P. J., Nigg E. A., Ono Y., Khanna K. K., (2005) Cdk1/Erk2- and Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of a centrosome protein, Cep55, is required for its recruitment to midbody and cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 9, 477–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martinez-Garay I., Rustom A., Gerdes H. H., Kutsche K., (2006) The novel centrosomal-associated protein CEP55 is present in the spindle midzone and the midbody. Genomics 87, 243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao W. M., Seki A., Fang G. (2006) Cep55, a microtubule-bundling protein, associates with centralspindlin to control the midbody integrity and cell abscission during cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3881–3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montoya M. (2007) An ESCRT for daughters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morita E., Sandrin V., Chung H. Y., Morham S. G., Gygi S. P., Rodesch C. K., Sundquist W. I. (2007) Human ESCRT and ALIX proteins interact with proteins of the midbody and function in cytokinesis. EMBO J. 26, 4215–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carlton J. G., Martin-Serrano J. (2007) Parallels between cytokinesis and retroviral budding. A role for the ESCRT machinery. Science 316, 1908–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlton J. G., Agromayor M., Martin-Serrano J. (2008) Differential requirements for Alix and ESCRT-III in cytokinesis and HIV-1 release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10541–10546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen C. H., Lu P. J., Chen Y. C., Fu S. L., Wu K. J., Tsou A. P., Lee Y. C., Lin T. C., Hsu S. L., Lin W. J., Huang C. Y., Chou C. K. (2007) FLJ10540-elicited cell transformation is through the activation of PI3-kinase/AKT pathway. Oncogene 26, 4272–4283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inoda S., Hirohashi Y., Torigoe T., Nakatsugawa M., Kiriyama K., Nakazawa E., Harada K., Takasu H., Tamura Y., Kamiguchi K., Asanuma H., Tsuruma T., Terui T., Ishitani K., Ohmura T., Wang Q., Greene M. I., Hasegawa T., Hirata K., Sato N. (2009) Cep55/c10orf3, a tumor antigen derived from a centrosome-residing protein in breast carcinoma. J. Immunother. 32, 474–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakai M., Shimokawa T., Kobayashi T., Matsushima S., Yamada Y., Nakamura Y., Furukawa Y. (2006) Elevated expression of C10orf3 (chromosome 10 open reading frame 3) is involved in the growth of human colon tumor. Oncogene 25, 480–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen C. H., Chien C. Y., Huang C. C., Hwang C. F., Chuang H. C., Fang F. M., Huang H. Y., Chen C. M., Liu H. L., Huang C. Y. (2009) Expression of FLJ10540 is correlated with aggressiveness of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma by stimulating cell migration and invasion through increased FOXM1 and MMP-2 activity. Oncogene 28, 2723–2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen C. H., Lai J. M., Chou T. Y., Chen C. Y., Su L. J., Lee Y. C., Cheng T. S., Hong Y. R., Chou C. K., Whang-Peng J., Wu Y. C., Huang C. Y. (2009) VEGFA up-regulates FLJ10540 and modulates migration and invasion of lung cancer via PI3K/AKT pathway. PLoS ONE 4, e5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang Y. C., Chen Y. J., Wu C. H., Wu Y. C., Yen T. C., Ouyang P. (2010) Characterization of centrosomal proteins Cep55 and pericentrin in intercellular bridges of mouse testes. J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 1274–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hollstein M., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Harris C. C. (1991) p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 253, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soussi T., Béroud C. (2001) Assessing TP53 status in human tumors to evaluate clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vousden K. H., Lu X. (2002) Live or let die. The cell's response to p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 594–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muller P. A., Vousden K. H., Norman J. C. (2011) p53 and its mutants in tumor cell migration and invasion. J. Cell Biol. 192, 209–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prives C., Hall P. A. (1999) The p53 pathway. J. Pathol. 187, 112–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sionov R. V., Haupt Y. (1999) The cellular response to p53. The decision between life and death. Oncogene 18, 6145–6157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dai C., Gu W. (2010) p53 post-translational modification. Deregulated in tumorigenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 528–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levine A. J. (1997) p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 88, 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu J., Zhang L. (2003) No PUMA, no death. Implications for p53-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell 4, 248–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. el-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sachdeva M., Zhu S., Wu F., Wu H., Walia V., Kumar S., Elble R., Watabe K., Mo Y. Y. (2009) p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3207–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pandit B., Halasi M., Gartel A. L. (2009) p53 negatively regulates expression of FoxM1. Cell Cycle 8, 3425–3427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sur S., Pagliarini R., Bunz F., Rago C., Diaz L. A., Jr., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N. (2009) A panel of isogenic human cancer cells suggests a therapeutic approach for cancers with inactivated p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3964–3969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKenzie L., King S., Marcar L., Nicol S., Dias S. S., Schumm K., Robertson P., Bourdon J. C., Perkins N., Fuller-Pace F., Meek D. W. (2010) p53-dependent repression of polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1). Cell Cycle 9, 4200–4212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van der Horst A., Simmons J., Khanna K. K. (2009) Cep55 stabilization is required for normal execution of cytokinesis. Cell Cycle 8, 3742–3749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gemenetzidis E., Bose A., Riaz A. M., Chaplin T., Young B. D., Ali M., Sugden D., Thurlow J. K., Cheong S. C., Teo S. H., Wan H., Waseem A., Parkinson E. K., Fortune F., Teh M. T. (2009) FOXM1 up-regulation is an early event in human squamous cell carcinoma, and it is enhanced by nicotine during malignant transformation. PLoS ONE 4, e4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kho P. S., Wang Z., Zhuang L., Li Y., Chew J. L., Ng H. H., Liu E. T., Yu Q. (2004) p53-regulated transcriptional program associated with genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21183–21192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Steegmaier M., Di Fiore B., Lipp J. J., Hoffmann M., Rettig W. J., Kraut N., Peters J. M., (2007) The small molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr. Biol. 17, 304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Plyte S., Musacchio A. (2007) PLK1 inhibitors. Setting the mitotic death trap. Curr. Biol. 17, R280–R283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steegmaier M., Hoffmann M., Baum A., Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Krssák M., Gürtler U., Garin-Chesa P., Lieb S., Quant J., Grauert M., Adolf G. R., Kraut N., Peters J. M., Rettig W. J. (2007) BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol. 17, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bartek J., Falck J., Lukas J. (2001) CHK2 kinase. A busy messenger. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 877–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bartek J., Lukas J. (2001) Mammalian G1- and S-phase checkpoints in response to DNA damage. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 738–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rozan L. M., El-Deiry W. S. (2007) p53 downstream target genes and tumor suppression. A classical view in evolution. Cell Death Differ. 14, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Böhlig L., Rother K. (2011) One function-multiple mechanisms: the manifold activities of p53 as a transcriptional repressor. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 464916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mundt K. E., Golsteyn R. M., Lane H. A., Nigg E. A. (1997) On the regulation and function of human polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). Effects of overexpression on cell cycle progression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 239, 377–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Vugt M. A., Medema R. H. (2005) Getting in and out of mitosis with Polo-like kinase-1. Oncogene 24, 2844–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Petronczki M., Lénárt P., Peters J. M. (2008) Polo on the Rise. From mitotic entry to cytokinesis with Plk1. Dev. Cell 14, 646–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takaki T., Trenz K., Costanzo V., Petronczki M. (2008) Polo-like kinase 1 reaches beyond mitosis. Cytokinesis, DNA damage response, and development. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 650–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kneisel L., Strebhardt K., Bernd A., Wolter M., Binder A., Kaufmann R. (2002) Expression of polo-like kinase (PLK1) in thin melanomas. A novel marker of metastatic disease. J. Cutan. Pathol. 29, 354–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weichert W., Denkert C., Schmidt M., Gekeler V., Wolf G., Köbel M., Dietel M., Hauptmann S. (2004) Polo-like kinase isoform expression is a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 90, 815–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weichert W., Schmidt M., Gekeler V., Denkert C., Stephan C., Jung K., Loening S., Dietel M., Kristiansen G. (2004) Polo-like kinase 1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and linked to higher tumor grades. Prostate 60, 240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van de Weerdt B. C., Medema R. H. (2006) Polo-like kinases. A team in control of the division. Cell Cycle 5, 853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bastos R. N., Barr F. A. (2010) Plk1 negatively regulates Cep55 recruitment to the midbody to ensure orderly abscission. J. Cell Biol. 191, 751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Myatt S. S., Lam E. W. (2007) The emerging roles of forkhead box (Fox) proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 847–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fu Z., Malureanu L., Huang J., Wang W., Li H., van Deursen J. M., Tindall D. J., Chen J. (2008) Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of FoxM1 regulates a transcriptional programme required for mitotic progression. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1076–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vousden K. H., Prives C. (2009) Blinded by the light. The growing complexity of p53. Cell 137, 413–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Inoda S., Morita R., Hirohashi Y., Torigoe T., Asanuma H., Nakazawa E., Nakatsugawa M., Tamura Y., Kamiguchi K., Tsuruma T., Terui T., Ishitani K., Hashino S., Wang Q., Greene M. I., Hasegawa T., Hirata K., Asaka M., Sato N. (2011) The feasibility of Cep55/c10orf3-derived peptide vaccine therapy for colorectal carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 90, 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Inoda S., Hirohashi Y., Torigoe T., Morita R., Takahashi A., Asanuma H., Nakatsugawa M., Nishizawa S., Tamura Y., Tsuruma T., Terui T., Kondo T., Ishitani K., Hasegawa T., Hirata K., Sato N. (2011) Cytotoxic T lymphocytes efficiently recognize human colon cancer stem-like cells. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1805–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schöffski P. (2009) Polo-like kinase (PLK) inhibitors in preclinical and early clinical development in oncology. Oncologist 14, 559–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chopra P., Sethi G., Dastidar S. G., Ray A. (2010) Polo-like kinase inhibitors. An emerging opportunity for cancer therapeutics. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 19, 27–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wäsch R., Hasskarl J., Schnerch D., Lübbert M. (2010) BI_2536. Targeting the mitotic kinase Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1). Recent Results Cancer Res. 184, 215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.