Background: The ECL2 of the GLP-1R is critical for GLP-1 peptide-mediated selective signaling.

Results: Mutation of most ECL2 residues to alanine results in changes in binding and/or efficacy of oxyntomodulin and exendin-4 but not allosteric agonists.

Conclusion: ECL2 of the GLP-1R has ligand-specific as well as general effects on peptide agonist-mediated receptor activation.

Significance: This work provides insight into control of family B GPCR activation transition.

Keywords: Cell Signaling, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Peptide Hormones, Receptor Structure-Function, Signal Transduction, Allosteric Agonist, Exendin, Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor, Ligand-directed Signaling Bias, Oxyntomodulin

Abstract

The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is a prototypical family B G protein-coupled receptor that exhibits physiologically important pleiotropic coupling and ligand-dependent signal bias. In our accompanying article (Koole, C., Wootten, D., Simms, J., Miller, L. J., Christopoulos, A., and Sexton, P. M. (2012) J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3642–3658), we demonstrate, through alanine-scanning mutagenesis, a key role for extracellular loop (ECL) 2 of the receptor in propagating activation transition mediated by GLP-1 peptides that occurs in a peptide- and pathway-dependent manner for cAMP formation, intracellular (Ca2+i) mobilization, and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (pERK1/2). In this study, we examine the effect of ECL2 mutations on the binding and signaling of the peptide mimetics, exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin, as well as small molecule allosteric agonist 6,7-dichloro-2-methylsulfonyl-3-tert-butylaminoquinoxaline (compound 2). Lys-288, Cys-296, Trp-297, and Asn-300 were globally important for peptide signaling and also had critical roles in governing signal bias of the receptor. Peptide-specific effects on relative efficacy and signal bias were most commonly observed for residues 301–305, although R299A mutation also caused significantly different effects for individual peptides. Met-303 was more important for exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin action than those of GLP-1 peptides. Globally, ECL2 mutation was more detrimental to exendin-4-mediated Ca2+i release than GLP-1(7–36)-NH2, providing additional evidence for subtle differences in receptor activation by these two peptides. Unlike peptide activation of the GLP-1R, ECL2 mutations had only limited impact on compound 2 mediated cAMP and pERK responses, consistent with this ligand having a distinct mechanism for receptor activation. These data suggest a critical role of ECL2 of the GLP-1R in the activation transition of the receptor by peptide agonists.

Introduction

The family B GPCR,3 GLP-1R, is an important target for the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus, and it has multiple endogenous ligands, including four forms of GLP-1, plus the related peptide oxyntomodulin (1, 2). Therapeutically, the mimetic peptide exendin-4 and metabolically stabilized forms of GLP-1 have recently been approved for treatment of type II diabetes mellitus (3, 4), although an oxyntomodulin derivative is also in clinical trials. In addition, there are a number of small molecule agonists/modulators that can augment responses via the GLP-1R (5–8), including the Novo Nordisk compound 2 (6). Exendin-4 is believed to closely mimic the actions of GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 at the receptor, but oxyntomodulin and the small molecule ligand, compound 2, display biased signaling relative to the truncated GLP-1 peptides (5, 6, 9). The molecular basis for these distinct actions is not known. Nonetheless, there is accumulating evidence that ECLs, in particular ECL2, may be important for peptide-mediated activation of family B GPCRs (10–17).

In our accompanying article (18), we demonstrate that individual amino acids within ECL2 play a critical role in the activation transition linking GLP-1 peptide binding to intracellular signaling (18) and that it is intimately linked to conformational control of signal bias initiated by peptide binding. However, peptide-specific differences in the effect of ECL2 mutations were also observed between GLP-1(1–36)-NH2 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 consistent with the ability of ECL2 to contribute to peptide-selective signal bias.

In this study, we have further explored the function of ECL2 and adjacent domains of the human GLP-1R through pharmacological characterization of the alanine-scanning mutants of ECL2 in the presence of the exogenous GLP-1 peptide mimetic exendin-4, the endogenous peptide agonist oxyntomodulin, or the allosteric agonist compound 2. We demonstrate that select ECL2 residues are critically involved in oxyntomodulin and exendin-4 binding and receptor activity, while also showing that ECL2 has little influence on compound 2 binding and activity, consistent with small molecule agonists having a distinct mode of action.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Compound 2 was generated in our laboratory, according to the method published previously (19), to a purity of >95%, and compound integrity was confirmed by NMR. Exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin were purchased from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA). All other reagents were obtained from suppliers as described in the accompanying article (18).

Methods

Receptor mutagenesis, cell transfection and cell culture, measurement of cell surface expression by antibody labeling of the c-Myc epitope, radioligand binding assays, cAMP accumulation, pERK1/2, and Ca2+i mobilization assays were each performed as described in our accompanying article (18). For pertussis toxin pretreatment experiments, cells were cultured in FBS-free DMEM containing 100 ng ml−1 pertussis toxin and incubated overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Data for these experiments were normalized to the maximal response elicited by peptide alone. All other data normalization was performed as described in our accompanying article (18).

Data analysis for determination of IC50, EC50, and operational measures of efficacy was performed as described in our accompanying article (18).

Statistics

Changes in ligand affinity, potency, efficacy, and cell surface expression of ECL2 mutants in comparison with wild type control were statistically analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test, and significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Cell Surface Expression of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutants

As reported in our accompanying article (18), cell surface expression determined through detection of the N-terminal double c-Myc epitope label was reduced for mutant receptors D293A, C296A, W297A, S301A, N304A, Y305A, and L307A, and it increased for N300A and M303A, although no significant changes were observed for the remaining mutants (Table 1). In most cases, specific binding of 125I-exendin(9–39) followed the same trend as antibody labeling. The exceptions to this were E294A and T298A that had increased specific 125I-exendin(9–39) binding in comparison with wild type control, but decreased or unchanged cell surface antibody labeling, and R299A that had decreased specific 125I-exendin(9–39) binding but unaltered cell surface antibody labeling. The W306A mutant, however, was not expressed at all at the cell surface and will not be described further.

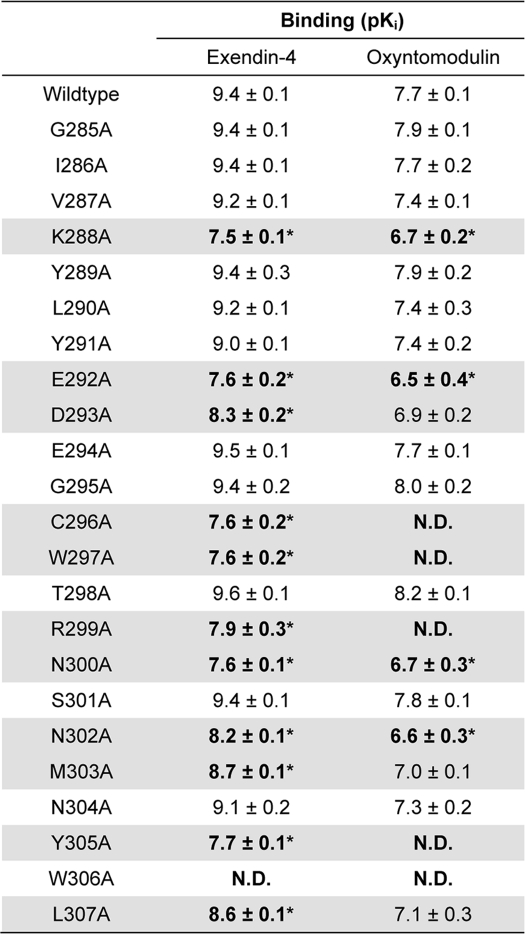

TABLE 1.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on peptide ligand binding and cell surface expression

Binding data were analyzed using a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. pIC50 values were then corrected for radioligand occupancy using the radioligand dissociation constant for each mutant, allowing determination of ligand affinity (Ki). All values are expressed as means ± S.E. of three to four independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. R2 values for curve fits were all >0.5. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicates data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with wild type response.

Select Mutants of the Human GLP-1R ECL2 Influence Exendin-4 and Oxyntomodulin Binding Affinity but Not Exendin(9–39) Affinity

Affinity of exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin at each of the mutants was assessed by competition for 125I-exendin(9–39) binding under equilibrium conditions (Table 1). There were no significant changes in binding affinity of exendin-4 or oxyntomodulin in comparison with the wild type control for receptor mutants G285A, I286A, V287A, Y289A, L290A, Y291A, E294A, G295A, T298A, S301A, and N304A, although decreases in affinity for both ligands were observed for receptor mutants K288A, E292A, D293A, C296A, W297A, R299A, N300A, N302A, M303A, Y305A, and L307A, as highlighted in gray in Table 1 (Fig. 1, B–E, and Table 1). This shading is maintained throughout all tables as an indication of mutants affected in binding affinity. Curves could not be accurately fitted for C296A and W297A in the presence of oxyntomodulin, most likely a result of the narrow window of signal generated by the significant decrease in specific 125I-exendin(9–39) binding (Table 1 of Ref. 18). In addition, binding affinity could not be determined for oxyntomodulin at mutant receptors R299A and Y305A due to incomplete curves, although reductions in binding affinity were apparent (Fig. 1). Notably, although the extent of affinity reduction of exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin was generally similar, differential effects of mutation were observed for the K288A, E292A, and N300A mutants with decreases in binding affinity of 79-, 63-, and 63-fold, respectively, for exendin-4, but only 10-, 16-, and 10-fold, respectively, for oxyntomodulin (Table 1).

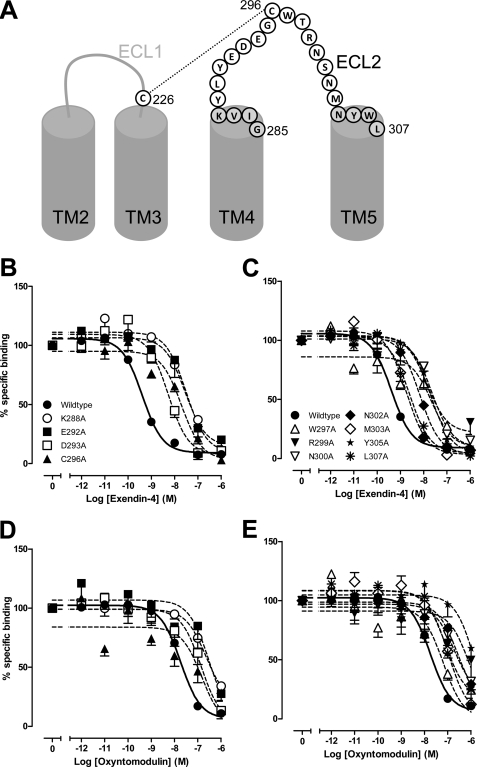

FIGURE 1.

Agonist binding profiles of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. A, schematic representation of the human GLP-1R ECL2, with disulfide interactions indicated (—) and boundaries indicated in gray shading. Characterization of the binding of exendin-4 (B and C) and oxyntomodulin (D and E) is in competition with the radiolabeled antagonist, 125I-exendin(9–39), in whole FlpInCHO cells stably expressing the wild type human GLP-1R or each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants that effect peptide binding affinity or the wild type GLP-1R. Data are normalized to maximum 125I-exendin(9–39) binding, with nonspecific binding measured in the presence of 1 μm exendin(9–39) and analyzed with a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. All values are means ± S.E. of three to four independent experiments, conducted in duplicate.

Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide-mediated cAMP Accumulation

The effect of mutation on ligand-induced cAMP formation was assessed via determination of potency and efficacy; the latter was estimated using an operational model corrected for receptor expression (τc, Table 2). Although both peptides were full agonists, exendin-4 had higher efficacy than oxyntomodulin in this system (logτc 1.03 ± 0.09 and 0.83 ± 0.07, respectively). With the exception of the M303A mutant, all mutants with reduced peptide agonist binding displayed reduced potency and efficacy, although the exendin-4 potency shift for R299A did not reach significance (Fig. 2, A, B, E, and F, and Table 2). The greatest effects on cAMP formation, for both peptides, were seen with the K288A and W297A mutants, with signaling essentially abolished at K288A and complete loss of oxyntomodulin signaling and marked attenuation of exendin-4 potency and efficacy at W297A (Fig. 2, A, B, E, and F, and Table 2). Similar reductions in responses elicited by both peptides were seen for the D293A, R299A, N302A, Y305A, and L307A mutants. In contrast, E292A, C296A, and N300A showed greater relative loss of exendin-4 potency, compared with that of oxyntomodulin with fold decreases in potency of 126, 100, and 316, respectively, for exendin-4 and 25, 32, and 20, respectively, for oxyntomodulin. This differential effect on potency was paralleled by greater decreases in binding affinity of exendin-4 for E292A and N300A, although the magnitude of effect on C296A affinity for oxyntomodulin could not be accurately determined (see above). Interestingly, at these mutants there was a correspondingly greater reduction in efficacy for oxyntomodulin relative to exendin-4, illustrating distinction in the impact of these residues on oxyntomodulin and exendin-4 function (Fig. 2, A and B, and Table 2).

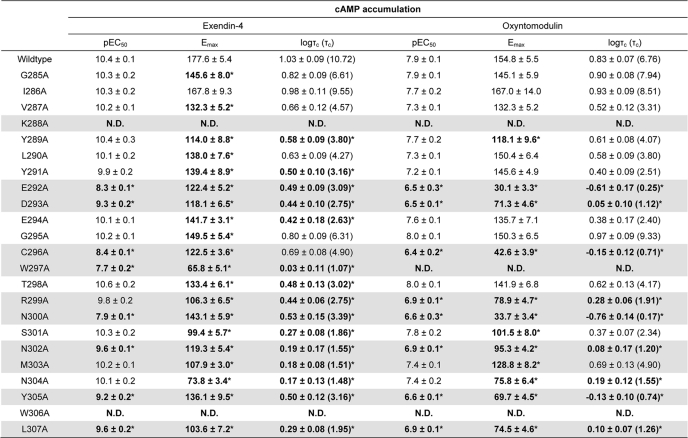

TABLE 2.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on peptide agonist signaling via cAMP

Data were analyzed using a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. pEC50 values represent the negative logarithm of the concentration of agonist that produces half the maximal response. Emax represents the maximal response normalized to that elicited by 100 μm forskolin. All mutants were analyzed with an operational model of agonism (Equation 2 of the accompanying article) to determine logτ values. All logτ values were then corrected to specific 125I- exendin(9–39) binding (logτc). Values are expressed as means ± S.E. of three to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. R2 values for the global curve fits were 0.87 for exendin-4 and 0.91 for oxyntomodulin, respectively. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicates data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with the wild type response.

FIGURE 2.

cAMP accumulation profiles of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. Characterization of cAMP accumulation in the presence of exendin-4 (A and C) and oxyntomodulin (B and D) in FlpInCHO cells stably expressing the wild type human GLP-1R or each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants that effect peptide binding affinity (A and B) or have no significant effect on peptide binding affinity (C and D). Data are normalized to the response elicited by 100 μm forskolin and analyzed with an operational model of agonism as defined in Equation 2 of the accompanying article. All values are means ± S.E. of three to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Visual representation of cAMP pathway coupling efficacy (logτc) in the presence of exendin-4 (E) and oxyntomodulin (F) is shown. Statistical significance of changes in coupling efficacy in comparison with wild type human GLP-1R was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test, and values are indicated with an asterisk (*, p < 0.05). All values are logτc ± S.E. of three to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate.

For those mutants that did not affect peptide binding, the effect on cAMP signaling was similar for both peptides. None of the mutants significantly altered potency of the peptides, although efficacy was also unaltered for the G285A, I286A, and G295A mutants (Fig. 2, C–F, and Table 2). All other mutants exhibited modest decreases in efficacy for the two peptides, although the effects did not always reach significance. The greatest effects on efficacy were seen with the S301A and N304A mutants (Fig. 2, E and F, and Table 2).

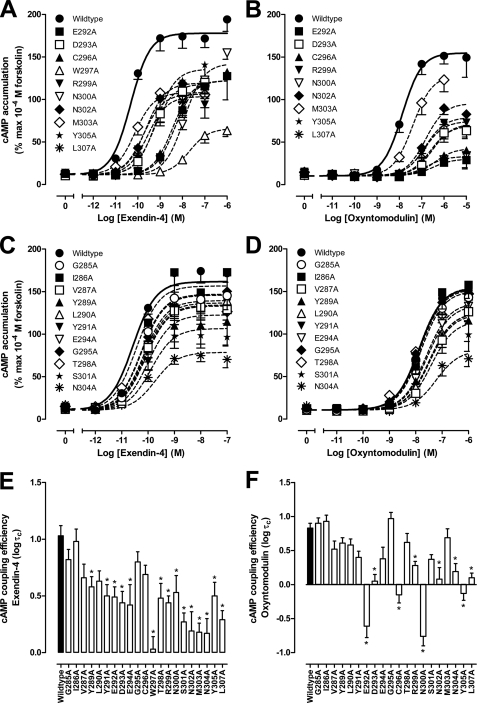

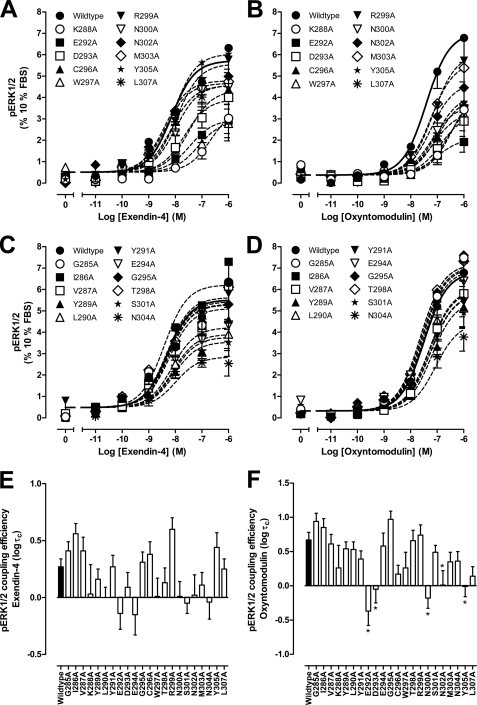

Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide-mediated pERK1/2

Peptide-induced pERK1/2 was determined at 6 min for each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. As noted in our accompanying article (18) for GLP-1(7–36)-NH2, ECL2 mutations globally had a lower impact on pERK1/2 relative to cAMP formation. There was also a generally greater impact on oxyntomodulin-induced signaling relative to that of exendin-4 (Fig. 3, A, B, E, and F, and Table 3). Only K288A had any effect on peptide potency, with decreased exendin-4 potency and a trend toward decreased potency for oxyntomodulin (Table 3). Of the other mutants that displayed reduced exendin-4 binding affinity, none had statistically significant effects on efficacy. For oxyntomodulin, significant loss of efficacy was observed for the E292A, D293A, N300A, N302A, and Y305A mutants. Whereas similar trends for lower efficacy were seen for exendin-4 at most of these mutants, Y305A efficacy was increased (Fig. 3, A, B, E, and F, and Table 3). No significant effects on efficacy were seen for either peptide or for the mutants that did not modulate peptide binding affinity (Fig. 3, C–F, and Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

pERK1/2 profiles of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. Characterization of pERK1/2 in the presence of exendin-4 (A and C) and oxyntomodulin (B and D) in FlpInCHO cells stably expressing the wild type human GLP-1R or each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants that effect peptide binding affinity (A and B) or have no significant effect on peptide binding affinity (C and D). Data are normalized to the maximal response elicited by 10% FBS and analyzed with an operational model of agonism as defined in Equation 2 of the accompanying article. All values are means ± S.E. of five to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Visual representation of pERK1/2 coupling efficacy (logτc) in the presence of exendin-4 (E) and oxyntomodulin (F) is shown. Statistical significance of changes in coupling efficacy in comparison with wild type human GLP-1R was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test, and values are indicated with an asterisk (*, p < 0.05). All values are logτc ± S.E. of five to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate.

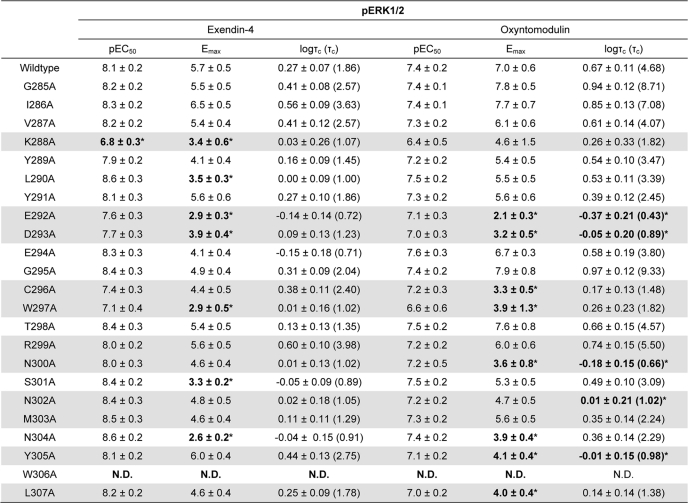

TABLE 3.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on peptide agonist signaling via pERK1/2

Data were analyzed using a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. pEC50 values represent the negative logarithm of the concentration of agonist that produces half the maximal response. Emax represents the maximal response normalized to that elicited by 10% FBS. All mutants were analyzed with an operational model of agonism (Equation 2 of the accompanying article) to determine logτ values. All logτ values were then corrected to specific 125I-exendin(9–39) binding (logτc). Values are expressed as means ± S.E. of five to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. R2 values for the global curve fits were 0.67 for exendin-4 and 0.66 for oxyntomodulin, respectively. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicates data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with wild type response.

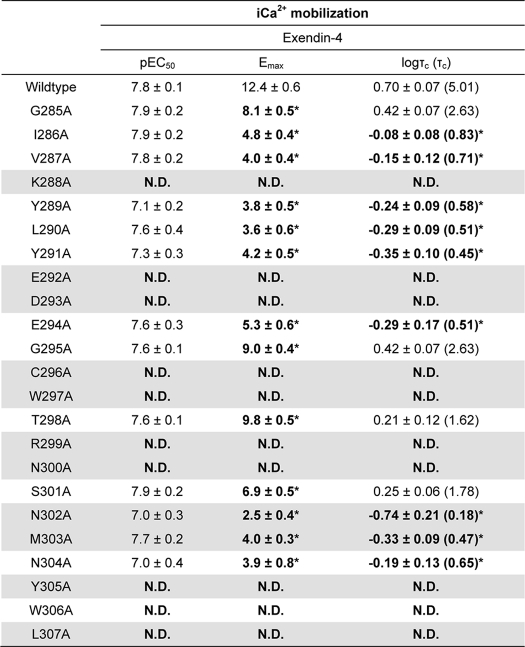

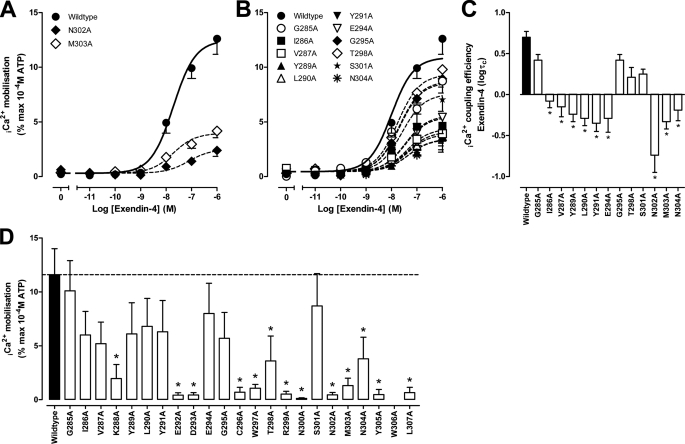

Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide-mediated Ca2+i Mobilization

Of the three signaling pathways studied, Ca2+i mobilization is the least well coupled and is also the one most affected by ECL2 mutations (Table 4). For the mutations that reduced exendin-4 binding affinity (K288A, E292A, D293A, C296A, W297A, R299A, N300A, Y305A, and L307A), there was effectively complete loss of exendin-4-mediated signaling and only weak responses for N302A and M303A, with marked reduction in efficacy, but no significant change in potency (Fig. 4A and Table 4). For mutants that did not alter exendin-4 affinity, reduced efficacy was also observed, with the exceptions being G285A, G295A, T298A, and S301A (Fig. 4, B and C, and Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on peptide agonist signaling via Ca2+i mobilization

Data were analyzed using a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 2 of the accompanying article. pEC50 values represent the negative logarithm of the concentration of agonist that produces half the maximal response. Emax represents the maximal response normalized to that elicited by 100 μm ATP. All mutants were analyzed with an operational model of agonism (Equation 2 of the accompanying article) to determine logτ values. All logτ values were then corrected to specific 125I-exendin(9– 39) binding (logτc). Values are expressed as means ± S.E. of four to five independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. The R2 value for the global curve fit was 0.85. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicates data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with wild type response.

FIGURE 4.

Ca2+i mobilization profiles of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. Characterization of Ca2+i mobilization in the presence of exendin-4 (A and B) in FlpInCHO cells stably expressing the wild type human GLP-1R or each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants that effect peptide binding affinity (A) or have no significant effect on peptide binding affinity (B) is shown. Data are normalized to the maximal response elicited by 100 μm ATP and analyzed with an operational model of agonism as defined in Equation 2 of the accompanying article. All values are means ± S.E. of four to five independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Visual representation of Ca2+i coupling efficacy (logτc) in the presence of exendin-4 (C) is shown. Statistical significance of changes in coupling efficacy in comparison with wild type human GLP-1R was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test, and values are indicated with an asterisk (*, p < 0.05). All values are logτc ± S.E. error of four to five independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data presented in D are levels of Ca2+i mobilization in the presence of 1 μm oxyntomodulin and are normalized to the maximal response elicited by 100 μm ATP. Statistical significance of changes in response in comparison with wild type human GLP-1R was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post-test, and values are indicated with an asterisk (*, p < 0.05). All values are means ± S.E. of three to five independent experiments, conducted in duplicate.

As observed previously (5, 9), oxyntomodulin has very weak coupling to Ca2+i mobilization, and full concentration-response curves could not be established over the concentration range assessed. Comparison of responses at the highest concentration used (1 μm) revealed reduced responses for each of the mutants that decreased oxyntomodulin affinity (K288A, E292A, D293A, C296A, W297A, R299A, N300A, N302A, M303A, Y305A, and L307A) (Fig. 4D). Reduced responses were also observed for T298A and N304A. Of note, no significant change in response was observed for E294A, despite a significantly reduced exendin-4 response (Fig. 4, B and D).

Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on the Function of the GLP-1R Allosteric Agonist, Compound 2

In addition to analyzing the effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 on peptide agonist binding and function, we also analyzed the effect of these mutants on binding and function of the GLP-1R allosteric agonist, compound 2 (Fig. 5 and Table 5) (5, 6). Compound 2 is a weak allosteric inhibitor of 125I-exendin(9–39) binding (5). Mutation of ECL2 had no effect on compound 2 inhibition of the radioligand relative to the wild type receptor, although for mutants with low specific 125I-exendin(9–39) binding (see Table 1 of Ref. 18), the effect of the mutations on compound 2-mediated inhibition of binding could not be robustly determined (data not shown).

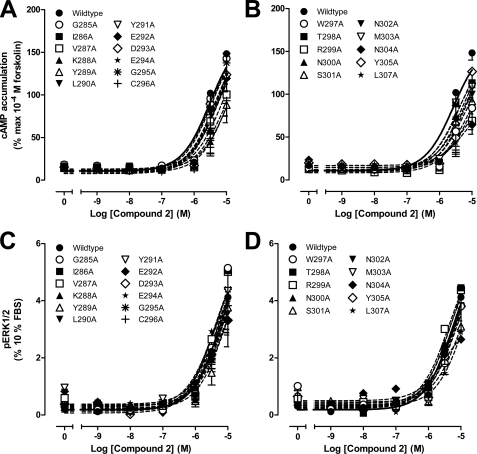

FIGURE 5.

Compound 2-mediated cAMP accumulation and pERK1/2 profiles of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. Characterization of cAMP accumulation (A and B) and pERK1/2 (C and D) in the presence of compound 2 in FlpInCHO cells stably expressing the wild type human GLP-1R or each of the human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants is shown. cAMP accumulation data are normalized to the response elicited by 100 μm forskolin, and pERK1/2 data are normalized to the maximal response elicited by 10% FBS, and all data are analyzed with a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. All values are means ± S.E. of four to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate.

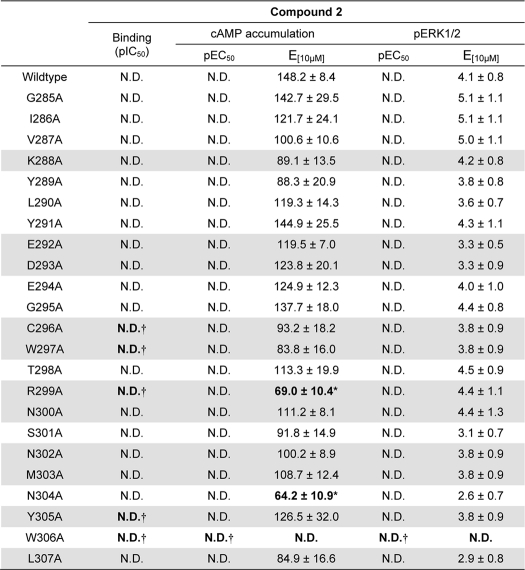

TABLE 5.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on the allosteric agonist compound 2

Data were analyzed using a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Equation 1 of the accompanying article. pEC50 values represent the negative logarithm of the concentration of agonist that produces half the maximal response. E[10 μM] in the data represents the response elicited at 10 μm compound 2, normalized to the response elicited by 100 μm forskolin (cAMP) or 10% FBS (pERK1/2). Values are expressed as means ± S.E. of four to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicate data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with wild type response.

† Profiles deviate from wild type, but pIC50 and/or pEC50 values for this ligand were unable to be determined in concentration range tested.

Compound 2 is a low potency but high efficacy partial agonist for GLP-1R-mediated increases in cAMP formation and a weak partial agonist for receptor-mediated pERK1/2 (5). The maximal concentration of compound 2 used in this study was 10 μm, which approaches the solubility limit of the compound. Although previous studies suggest that this concentration elicits a near maximal cAMP response (5, 9), the upper plateau of the concentration-response curve was not fully defined in this study, preventing application of the operational model fitting to the data and determination of efficacy-related effects independent of receptor expression. Analysis of the effect of mutations on cAMP formation revealed limited impact on compound 2-mediated signaling with no change to potency and only small decreases in maximal response (Fig. 5, A and B, and Table 5). The decreases observed in maximal response were paralleled by decreases in functional cell surface receptor expression (18), suggesting that this likely underlies loss of signaling rather than a direct effect on receptor activation by compound 2. There was no significant alteration to potency or maximal response to compound 2-mediated pERK1/2 for any of the ECL2 mutants (Fig. 5, C and D, and Table 5).

Human GLP-1R ECL2 Is Critical for Peptide-mediated Activation Transition of GLP-1R

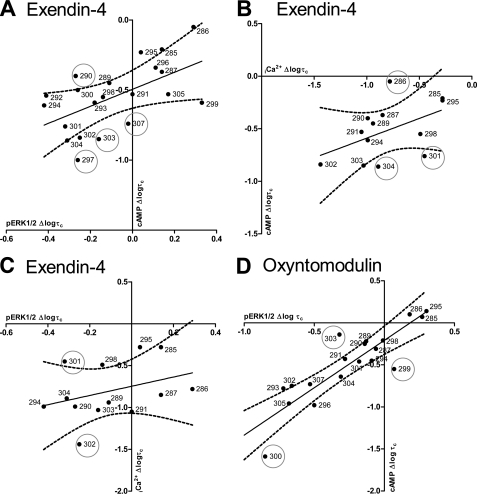

Overall, there was a strong correlation of the effect of the mutations on changes to efficacy for peptide-mediated cAMP and pERK1/2, albeit that the changes were not necessarily in the same direction, and this was particularly true for oxyntomodulin responses (Fig. 6). A lower degree of correlation was seen between the effect of mutation on exendin-4 between either cAMP or pERK1/2 and Ca2+i (Fig. 6, B and C), although this is likely related, at least in part, to the large number of mutants without a measurable Ca2+i response to this peptide. Globally, this is consistent with a key role for ECL2 in the generation of the ensemble of receptor conformations linked to signaling responses. The relative preservation, or even increase, in pERK1/2 response upon ECL2 mutation relative to the other signaling pathways suggests that the ensemble of conformations mediating pERK1/2 are quite distinct from those linked to cAMP formation and Ca2+i mobilization. Nonetheless, although the data are consistent with a major role of ECL2 in conformational propagation, there were clear examples where individual mutation had pathway-selective effects on efficacy. For oxyntomodulin, there was a very tight correlation between the effect of most mutations on pERK1/2 and cAMP efficacy. The exceptions to this were the R299A and M303A mutants (Fig. 6D), indicating differential effects on oxyntomodulin-mediated signaling. For the M303A mutation this manifests as a minimal loss of cAMP signaling compared with pERK1/2, although for the R299A mutation there was a relatively greater loss of cAMP signaling. For exendin-4, there was proportionally greater loss of cAMP efficacy relative to pERK1/2 efficacy for M303A, L307A, and W297A, although L290A exhibited relatively preserved cAMP efficacy relative to the loss of pERK1/2 signaling. The outliers for exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin were mostly distinct from those observed with the GLP-1 peptides (18), although R299A, L290A, and W297A were also among those residues that exhibited noncorrelative effects across different pathways. For the GLP-1 peptides, N304A also displayed pathway- and peptide-dependent effects on efficacy, although this residue displayed mostly consistent effects across pathways for exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin. Thus, although ECL2 is globally important for receptor activation, individual residues likely contribute to secondary structure that is important for peptide-specific receptor activation.

FIGURE 6.

Correlation plots of pathway efficacy (logτc) of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants. Correlation plots of changes in pathway coupling efficacy (logτc) of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants with respect to wild type receptor are shown. A, pERK1/2 versus cAMP for exendin-4; B, Ca2+i versus cAMP for exendin-4; C, pERK1/2 versus Ca2+i for exendin-4; and D, pERK1/2 versus cAMP for oxyntomodulin. Data were fit by linear regression. The line of regression and 99% confidence intervals (—) are displayed.

Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide-mediated Signal Bias

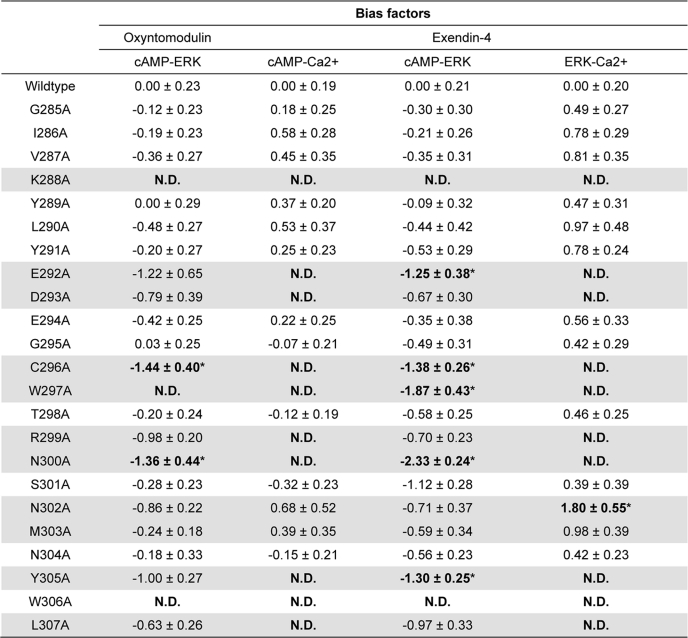

Bias plots provide a useful tool for comparing relative bias of peptides across two pathways independent of absolute potency (20). Visualization of signaling in this manner revealed strong relative bias of exendin-4 for cAMP formation relative to pERK1/2, with weaker relative bias for pERK1/2 over Ca2+i mobilization (supplemental Fig. S1, A–C). In contrast, oxyntomodulin was only weakly biased toward cAMP signaling relative to pERK1/2 (supplemental Fig. S1D) but was poorly coupled to Ca2+i mobilization. Whereas most mutations had minimal effect on bias (although distinct effects on efficacy could be distinguished), a number of mutations appeared to be critically important for maintaining pathway bias, albeit in a peptide-dependent manner (Table 6 and supplemental Fig. S1). Asn-300 appeared to play a critical role in maintaining pathway bias of exendin-4, oxyntomodulin, and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 (18) toward cAMP formation over pERK1/2 and likely has a similar influence on GLP-1(1–36)-NH2, where cAMP formation was completely abrogated (18). For all three peptides, there was a complete reversal of bias with this mutant for these two pathways (supplemental Fig. S1, A and D) (18). Trp-297 was similarly important for exendin-4 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 (18) and a prerequisite for cAMP signaling at the weaker agonist peptides. Arg-299, Asn-302, and Cys-296 were important for maintaining oxyntomodulin and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 (18) bias for cAMP over pERK1/2 but were less critical for exendin-4-mediated bias (Table 6 and supplemental Fig. S1). Mutation of Arg-299 and Tyr-305 to alanine also promoted bias toward pERK1/2 for GLP-1(1–36)-NH2 (18). The N304A mutation, however, was associated with a preferential loss of cAMP signaling over pERK1/2 for GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 and GLP-1(1–36)-NH2 (18) and to a lesser extent exendin-4, with limited impact on oxyntomodulin.

TABLE 6.

Effects of human GLP-1R ECL2 alanine mutants on exendin-4- and oxyntomodulin-mediated signaling bias

Data were analyzed using an operational model of agonism as defined in Equation 4 of the accompanying article to estimate logτc/KA ratios. Changes in logτc/KA ratios with respect to wild type were used to quantitate bias between signaling pathways. Values are expressed as means ± S.E. of three to seven independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's post test. Gray shading highlights residues effecting peptide agonist binding affinity. ND indicates data unable to be experimentally defined.

* Data are statistically significant at p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, and Dunnett's post test in comparison with wild type response.

DISCUSSION

There is increasing evidence that the ECL2 of family A GPCRs plays a critical role in activation transition of GPCRs as well as being an important region for allosteric modulation of receptors (14, 20–26). In this study, we have used alanine scanning of residues of ECL2 and adjacent amino acids to examine the role of these residues in binding and signaling mediated by peptide and nonpeptide ligands of the GLP-1R, a family B GPCR. Exendin-4 is a high affinity GLP-1 peptide mimetic currently approved for clinical treatment of type II diabetics (3, 27, 28), although oxyntomodulin is a naturally occurring GLP-1R peptide ligand with intermediate potency between full-length and truncated GLP-1 peptides (1, 29). In accord with observations for GLP-1 peptides in our accompanying article (18), ECL2 was critically important for activation transition of the GLP-1R by exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin, albeit with distinctions in the involvement of individual residues. In contrast, activation of the receptor by the small molecule agonist, compound 2, was relatively unaffected by ECL2 mutations, with most effects tracking with loss in cell surface receptor expression. As such, ECL2 appeared to play only a limited role in compound 2-mediated receptor activation.

As also noted for GLP-1 peptides (18), residues that were highly conserved across family B peptide hormone receptors (Lys-288, Asp-293, Cys-296, Trp-297, and Trp-306) were among those most critical for receptor function, demonstrating marked loss in agonist peptide binding and marked attenuation of peptide-mediated signaling. W306A was not expressed at the cell surface and consequently could not be examined further. Of the others, K288A was the most deleterious, and this likely relates to a critical structural role for this residue for peptide-mediated actions. We have previously speculated that this may be involved in stabilization of the top of TM4 by “snorkeling” (18), which may be required for correct orientation of ECL2 for peptide-mediated receptor activation. Nonetheless, this was not critical to compound 2-mediated receptor activation, indicating that this ligand activates the receptor in a unique manner as discussed below. Although Cys-296 and Trp-297 are highly conserved and likely to be structurally important for the entire B receptor subfamily (see Fig. 1A of Ref. 18), they also appear to contribute to signal bias of high affinity peptide agonists of the GLP-1R (supplemental Fig. S1). Cys-296 is predicted to form a disulfide bridge with Cys-226 at the top of TM3 in a similar manner to family A GPCRs (30), providing conformational restriction on the movement of ECL2. Residues distal to this amino acid likely contribute to propagation of conformational rearrangement of TM5 that has been shown to undergo translational movements on the intracellular face of the receptor for agonist-occupied G protein-coupled β2-adrenoreceptor (31–33), and this is likely important in receptor activation. Consistent with this, residues distal to Cys-296 generally had a greater impact on receptor signaling.

Comparison of Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide Binding and Function, Exendin-4 Versus Oxyntomodulin

For mutants at which binding affinity could robustly be estimated for both peptides, most mutants had comparable effects on affinity. The exceptions were C296A, W297A, R299A, and Y305A, where affinity estimates could not be determined for oxyntomodulin due to incomplete or poorly defined curves, and K288A, E292A, and N300A, where there was greater loss of exendin-4 affinity relative to that of oxyntomodulin. Each of these was among the most profoundly affected mutants for exendin-4 affinity and may, at least in part, reflect differences in affinity of the two peptides for active versus inactive states of the receptor, as discussed below.

Although the effect of ECL2 mutation on peptide-mediated cAMP formation was generally similar for exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin, three mutations, E292A, C296A, and N300A, had differential effects for the two peptides. In each case, there was a greater effect on exendin-4 potency that paralleled the differential effect on binding affinity between the peptides. At each of these mutants, however, oxyntomodulin efficacy was reduced to a greater extent than the equivalent mutation on exendin-4 response, with respect to wild type. Nonetheless, the changes to cAMP signaling likely reflect a mechanistically similar effect across the two peptides. For these three mutants, the oxyntomodulin potency and estimates of affinity are equivalent. Operationally, loss of efficacy is manifested as a collapse of the potency toward the affinity value of peptides with subsequent diminution of maximal response. Where changes in agonist peptide affinity occur, this may be due to decreased ability to form the active, high affinity ARG ternary complex, wherein the measured affinity collapses to the affinity for the inactive state receptor (34). Although there may be direct effects of the mutations on ligand contact and affinity, the data are principally consistent with decreased ability to form G protein-complexed receptors.

In contrast, the M303A mutant had distinct effects on the efficacy of exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin in the absence of altered potency with selective loss of exendin-4 efficacy. As described above, this mutant was also an outlier in the correlation analyses of cAMP versus pERK1/2 signaling for both peptides (supplemental Fig. S1). Thus Met-303 appears to play a distinct role for cAMP formation (and by inference Gαs coupling) for these peptides with GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 exhibiting an intermediate profile (supplemental Fig. S2) (9).

Although operational measures of oxyntomodulin efficacy for Ca2+i mobilization could not be determined due to the weak response, comparison of the maximal effect of oxyntomodulin at 1 μm with the responses to exendin-4 revealed apparent differences in the effect of mutation on Ca2+i signaling for the two peptides, with preservation of oxyntomodulin responses for L290A, Y291A, and E294A, and significant loss of exendin-4 signaling. For these mutants, there was no significant decrease in 125I-exendin(9–39) binding (see Table 1 of Ref. 18) suggesting that there was a similar level of functional cell surface receptors. Ca2+i responses to GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 were also decreased at these four mutants, suggesting that there are differences in how oxyntomodulin, and the high affinity peptides modulate Ca2+i signaling.

Comparison of Effect of Human GLP-1R ECL2 Alanine Mutations on Peptide Function, Exendin-4 Versus GLP-1(7–36)-NH2

Exendin-4 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 are generally considered to interact with and activate the receptor in an equivalent manner, and indeed, the efficacy of these two peptides for the three pathways studied was very similar (Tables 2–4 of this paper and Ref. 18). This was also generally reflected in the effect of mutation on the function of the two peptides. Nonetheless, some subtle differences in responses were observed (supplemental Fig. S2). In the assay of cAMP formation, all except two of the mutants had effectively equivalent magnitude of potency alteration (<0.5 log unit difference); the exceptions were R299A and L307A that exhibited greater loss in potency for GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 compared with exendin-4. The effect on efficacy of the two peptides was also similar; however, residues after Cys-296 had greater loss of exendin-4 efficacy relative to GLP-1(7–36)-NH2, with the exception of N300A that had the opposite effect. This suggests that translation of exendin-4 signaling to Gαs coupling is more reliant on structural conservation of the distal segment of ECL2.

There was also a strong correlation between the effect of mutants on exendin-4 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 efficacy for pERK1/2. Nonetheless, the N300A mutant appeared to discriminate between the two peptides, and indeed this was true for oxyntomodulin and GLP-1(1–36)-NH2 (see Table 3 of Ref. 18), with a rank order for loss of efficacy of GLP-1(1–36)-NH2 > oxyntomodulin > GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 > exendin-4. As described above, the Asn-300 residue is also linked to signal bias of peptides between cAMP and pERK1/2 for exendin-4, GLP-1(7–36)-NH2, and oxyntomodulin and suggests that it makes critical intra-receptor interactions that underlie this effect.

Although the efficacy for exendin-4 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 was similar at the wild type receptor in Ca2+i signaling (logτc 0.70 ± 0.07 and 0.63 ± 0.08 (18), respectively), there was greater relative loss of exendin-4 Ca2+i signaling with mutation of ECL2. This was manifest as virtual abolishment of exendin-4-mediated responses for E293A, R299A, Y305A, and L307A, although reduced but measurable responses were observed with GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 (18). This differential effect on Ca2+i may be due to differences in the mechanism of receptor coupling to Ca2+i signaling for the two peptides; exendin-4 signaling was relatively insensitive to pertussis toxin pretreatment (reduced 28.7 ± 8.3%), whereas the GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 response was attenuated by 37.0 ± 7.1% (supplemental Fig. S3) indicating that Gαi/o proteins play a greater role in GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 signaling linked to Ca2+i mobilization. Although not conclusive, the Gαi/o response may be less dependent upon conformational propagation through ECL2.

Generically, the inability to couple to Ca2+ in the cases of K288A, E292A, D293A, C296A, W297A, R299A, Y305A, and L307A in the presence of exendin-4 was also reflected in severe impairment to couple to the cAMP pathway, suggesting that these residues are perhaps not important in pathway selectivity between cAMP and Ca2+. However, receptor mutants C296A, R299A, and Y305A all demonstrated increased ability to couple to pERK1/2 despite no detectable signaling through the Ca2+i pathway, suggesting some involvement in pathway selectivity at these residues. Additionally, although N302A and M303A had some ability to couple to the Ca2+i pathway when activated by exendin-4, it was noted that these were two of the most severely impaired mutant receptors in cAMP coupling but also only had small reductions in pERK1/2 coupling, which may indicate importance in pathway selectivity at these residues. These results suggest that ECL2 has a greater influence on Ca2+i activation by exendin-4 than other signaling pathways.

Collectively, the data suggest that exendin-4 and GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 likely activate the receptor via subtly different mechanisms, and this may have implications for their use as therapeutic agents. Indeed, the evidence for different mechanisms of activity is also seen with mutation of Lys-288 at the rat GLP-1R, with significantly greater decreases in binding affinity of GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 than exendin-4 (13). Furthermore, the affinity of GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 is highly sensitive to N-terminal truncation, whereas exendin-4 is not; exendin-4 can be truncated by up to eight residues without significant loss of binding affinity for the GLP-1R (35). In addition, despite identical homology in the N-terminal seven residues, GLP-1(9–36)-NH2 is a partial agonist, although exendin(3–39) is an antagonist (35). Although this is most likely a composite of both N- and C-terminal peptide interactions with the receptor, these differences in GLP-1 and exendin-4 binding and function are supportive of differential mechanisms of activation at the GLP-1R (36–38).

Distinct Receptor Activation Mechanisms for Peptide and Small Molecule Agonists

In contrast to the dramatic effects on peptide-mediated binding and signaling, mutation of ECL2 residues had limited impact on activation of the receptor by the small molecule agonist compound 2. In the cases where there was a reduction in cAMP Emax, there was a parallel loss in functional receptors at the cell surface that may account for the effect of these mutations. Likewise, there was little effect on signal bias for compound 2 across the mutants, with observed alterations paralleling loss of cAMP signaling that accompanied lower functional cell surface receptor expression (supplemental Fig. S1E). A similar distinction in effect on peptide versus small molecule activation of the receptor was seen for the inactivating polymorphic variant Met-149, which selectively attenuated GLP-1(7–36)-NH2 and exendin-4, but not compound 2 signaling (9). At this variant, compound 2 could also allosterically rescue peptide activation of the receptor (9). Collectively, these data provide evidence for distinct modes of receptor activation for peptide and nonpeptide agonists, with peptide-mediated activation of the receptor critically involving conformational propagation through ECL2, although compound 2-mediated activation appears to principally occur independently of this.

The conformational transition leading to interaction with signaling effectors in response to agonist occupation of the receptor is thought to involve reorganization of hydrogen bonding networks within the transmembrane domain of the receptors leading to marked changes in the intracellular face of the receptor (31–33). How agonists bind to the receptor to mediate these effects is still mostly unclear. In this study, we have provided evidence for a critical role of the ECL2 of the GLP-1R in propagating this conformational change upon peptide binding, and also for directing signaling bias at this receptor. The data also suggest that individual peptides differentially influence ECL2 to mediate their effects, although the small molecule agonist, compound 2, has a distinct mechanism for receptor activation.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grant 1002180 and Program Grant 519461 and by a National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (to P. M. S.) and a Senior Research Fellowship (to A. C.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- compound 2

- 6,7-dichloro-2-methylsulfonyl-3-tert-butylaminoquinoxaline

- GLP-1R

- glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor

- Ca2+i

- intracellular calcium.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fehmann H. C., Jiang J., Schweinfurth J., Wheeler M. B., Boyd A. E., 3rd, Göke B. (1994) Stable expression of the rat GLP-I receptor in CHO cells. Activation and binding characteristics utilizing GLP-I(7–36)-amide, oxyntomodulin, exendin-4, and exendin(9–39). Peptides 15, 453–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baggio L. L., Drucker D. J. (2007) Biology of incretins. GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 132, 2131–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furman B. L. (2010) The development of Byetta (exenatide) from the venom of the Gila monster as an antidiabetic agent. Toxicon, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drucker D. J., Dritselis A., Kirkpatrick P. (2010) Liraglutide. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 267–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koole C., Wootten D., Simms J., Valant C., Sridhar R., Woodman O. L., Miller L. J., Summers R. J., Christopoulos A., Sexton P. M. (2010) Allosteric ligands of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) differentially modulate endogenous and exogenous peptide responses in a pathway-selective manner. Implications for drug screening. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 456–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knudsen L. B., Kiel D., Teng M., Behrens C., Bhumralkar D., Kodra J. T., Holst J. J., Jeppesen C. B., Johnson M. D., de Jong J. C., Jorgensen A. S., Kercher T., Kostrowicki J., Madsen P., Olesen P. H., Petersen J. S., Poulsen F., Sidelmann U. G., Sturis J., Truesdale L., May J., Lau J. (2007) Small molecule agonists for the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 937–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irwin N., Flatt P. R., Patterson S., Green B. D. (2010) Insulin-releasing and metabolic effects of small molecule GLP-1 receptor agonist 6,7-dichloro-2-methylsulfonyl-3-N-tert-butylaminoquinoxaline. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 628, 268–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sloop K. W., Willard F. S., Brenner M. B., Ficorilli J., Valasek K., Showalter A. D., Farb T. B., Cao J. X., Cox A. L., Michael M. D., Gutierrez Sanfeliciano S. M., Tebbe M. J., Coghlan M. J. (2010) Novel small molecule glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist stimulates insulin secretion in rodents and from human islets. Diabetes 59, 3099–3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koole C., Wootten D., Simms J., Valant C., Miller L. J., Christopoulos A., Sexton P. M. (2011) Polymorphism and ligand-dependent changes in human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) function. Allosteric rescue of loss of function mutation. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 486–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoare S. R. (2005) Mechanisms of peptide and nonpeptide ligand binding to Class B G-protein-coupled receptors. Drug Discov. Today 10, 417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coopman K., Wallis R., Robb G., Brown A. J., Wilkinson G. F., Timms D., Willars G. B. (2011) Residues within the transmembrane domain of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor involved in ligand binding and receptor activation. Modeling the ligand-bound receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 1804–1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller L. J., Chen Q., Lam P. C., Pinon D. I., Sexton P. M., Abagyan R., Dong M. (2011) Refinement of glucagon-like peptide 1 docking to its intact receptor using mid-region photolabile probes and molecular modeling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15895–15907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Al-Sabah S., Donnelly D. (2003) The positive charge at Lys-288 of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor is important for binding the N terminus of peptide agonists. FEBS Lett. 553, 342–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holtmann M. H., Ganguli S., Hadac E. M., Dolu V., Miller L. J. (1996) Multiple extracellular loop domains contribute critical determinants for agonist binding and activation of the secretin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14944–14949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Assil-Kishawi I., Abou-Samra A. B. (2002) Sauvagine cross-links to the second extracellular loop of the corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32558–32561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liaw C. W., Grigoriadis D. E., Lovenberg T. W., De Souza E. B., Maki R. A. (1997) Localization of ligand-binding domains of human corticotropin-releasing factor receptor. A chimeric receptor approach. Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 980–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergwitz C., Jusseaume S. A., Luck M. D., Jüppner H., Gardella T. J. (1997) Residues in the membrane-spanning and extracellular loop regions of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)-2 receptor determine signaling selectivity for PTH and PTH-related peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28861–28868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koole C., Wootten D., Simms J., Miller L. J., Christopoulos A., Sexton P. M. (2012) Second extracellular loop of human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) has a critical role in GLP-1 peptide binding and receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3642–3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teng M., Johnson M. D., Thomas C., Kiel D., Lakis J. N., Kercher T., Aytes S., Kostrowicki J., Bhumralkar D., Truesdale L., May J., Sidelman U., Kodra J. T., Jørgensen A. S., Olesen P. H., de Jong J. C., Madsen P., Behrens C., Pettersson I., Knudsen L. B., Holst J. J., Lau J. (2007) Small molecule ago-allosteric modulators of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 (hGLP-1) receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17, 5472–5478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gregory K. J., Hall N. E., Tobin A. B., Sexton P. M., Christopoulos A. (2010) Identification of orthosteric and allosteric site mutations in M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors that contribute to ligand-selective signaling bias. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7459–7474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Avlani V. A., Gregory K. J., Morton C. J., Parker M. W., Sexton P. M., Christopoulos A. (2007) Critical role for the second extracellular loop in the binding of both orthosteric and allosteric G protein-coupled receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25677–25686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conner M., Hawtin S. R., Simms J., Wootten D., Lawson Z., Conner A. C., Parslow R. A., Wheatley M. (2007) Systematic analysis of the entire second extracellular loop of the V(1a) vasopressin receptor. Key residues, conserved throughout a G-protein-coupled receptor family, identified. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17405–17412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahn K. H., Bertalovitz A. C., Mierke D. F., Kendall D. A. (2009) Dual role of the second extracellular loop of the cannabinoid receptor 1. Ligand binding and receptor localization. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 833–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scarselli M., Li B., Kim S. K., Wess J. (2007) Multiple residues in the second extracellular loop are critical for M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7385–7396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawtin S. R., Simms J., Conner M., Lawson Z., Parslow R. A., Trim J., Sheppard A., Wheatley M. (2006) Charged extracellular residues, conserved throughout a G-protein-coupled receptor family, are required for ligand binding, receptor activation, and cell-surface expression. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38478–38488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ott T. R., Troskie B. E., Roeske R. W., Illing N., Flanagan C. A., Millar R. P. (2002) Two mutations in extracellular loop 2 of the human GnRH receptor convert an antagonist to an agonist. Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 1079–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kolterman O. G., Kim D. D., Shen L., Ruggles J. A., Nielsen L. L., Fineman M. S., Baron A. D. (2005) Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 62, 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Göke R., Fehmann H. C., Linn T., Schmidt H., Krause M., Eng J., Göke B. (1993) Exendin-4 is a high potency agonist and truncated exendin-(9–39)-amide an antagonist at the glucagon-like peptide 1-(7–36)-amide receptor of insulin-secreting beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 19650–19655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidtler J., Dehne K., Allescher H. D., Schusdziarra V., Classen M., Holst J. J., Polack A., Schepp W. (1994) Rat parietal cell receptors for GLP-1-(7–36) amide. Northern blot, cross-linking, and radioligand binding. Am. J. Physiol. 267, G423–G432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mann R. J., Al-Sabah S., de Maturana R. L., Sinfield J. K., Donnelly D. (2010) Functional coupling of Cys-226 and Cys-296 in the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor indicates a disulfide bond that is close to the activation pocket. Peptides 31, 2289–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rasmussen S. G., Choi H. J., Fung J. J., Pardon E., Casarosa P., Chae P. S., Devree B. T., Rosenbaum D. M., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Schnapp A., Konetzki I., Sunahara R. K., Gellman S. H., Pautsch A., Steyaert J., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2011) Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the β(2) adrenoceptor. Nature 469, 175–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rasmussen S. G., Devree B. T., Zou Y., Kruse A. C., Chung K. Y., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Chae P. S., Pardon E., Calinski D., Mathiesen J. M., Shah S. T., Lyons J. A., Caffrey M., Gellman S. H., Steyaert J., Skiniotis G., Weis W. I., Sunahara R. K., Kobilka B. K. (2011) Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenbaum D. M., Zhang C., Lyons J. A., Holl R., Aragao D., Arlow D. H., Rasmussen S. G., Choi H. J., Devree B. T., Sunahara R. K., Chae P. S., Gellman S. H., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E., Weis W. I., Caffrey M., Gmeiner P., Kobilka B. K. (2011) Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β(2) adrenoceptor complex. Nature 469, 236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kobilka B. K., Deupi X. (2007) Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Montrose-Rafizadeh C., Yang H., Rodgers B. D., Beday A., Pritchette L. A., Eng J. (1997) High potency antagonists of the pancreatic glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21201–21206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al-Sabah S., Donnelly D. (2003) A model for receptor-peptide binding at the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor through the analysis of truncated ligands and receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140, 339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Al-Sabah S., Donnelly D. (2004) The primary ligand-binding interaction at the GLP-1 receptor is via the putative helix of the peptide agonists. Protein Pept. Lett. 11, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mann R., Nasr N., Hadden D., Sinfield J., Abidi F., Al-Sabah S., de Maturana R. L., Treece-Birch J., Willshaw A., Donnelly D. (2007) Peptide binding at the GLP-1 receptor. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 713–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.