Abstract

Objective:

Men’s heavy drinking has been established as a risk factor for their perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV); however, the role of women’s drinking in their perpetration of IPV is less clear. The current study examined the relative strength of husbands’ and wives’ alcohol use and alcohol dependence symptoms on the occurrence and frequency of husbands’ and wives’ IPV perpetration.

Method:

Married and cohabiting community couples (N = 280) were identified and recruited according to their classification in one of four drinking groups: heavy episodic drinking occurred in both partners (n = 79), the husband only (n = 80), the wife only (n = 41), and neither (n = 80). Husband and wife alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence symptoms, and IPV perpetration were assessed independently for both partners.

Results:

Husband and wife consumption and alcohol dependence symptoms contributed to the likelihood and frequency of husband IPV, both independently and interactively. Husband, but not wife, alcohol dependence symptoms contributed to the occurrence of any wife IPV, although both partners’ alcohol dependence symptoms predicted the frequency of wife aggression. Couples with discrepant drinking were not more likely to perpetrate IPV.

Conclusions:

Findings for husband IPV support previous research identifying alcohol use of both partners as a predictor. However, for wives, alcohol appears to play less of a role in IPV perpetration, perhaps reflecting that women experience less inhibition against physical aggression in their intimate relationships than do men.

A substantial body of research indicates that men’s alcohol use and alcohol problems predict their perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV; Foran and O’Leary, 2008; Lipsey et al., 1997). Significant cross-sectional relationships between alcohol use and IPV have been observed among representative community or household samples (Kantor and Straus, 1989; White and Chen, 2002), people seeking primary or emergency medical care (Coker et al., 2000; Kyriacou et al., 1999), and couples in which the husband is seeking alcohol treatment (O’Farrell et al., 2003).

Because IPV was initially conceptualized as involving male-to-female violence (Straus and Gelles, 1986), fewer studies have considered female-perpetrated IPV. In a recent meta-analysis of alcohol and IPV, there were only 8 studies that considered female-perpetrated IPV compared with 47 studies that examined male-perpetrated IPV (Foran and O’Leary, 2008). This meta-analysis concluded that the effect size for men’s alcohol use and perpetration of IPV was significant and of medium size, whereas for women the effect was small, based on a limited number of studies. More research considering women’s perpetration of IPV would increase confidence regarding the role of women’s alcohol use in their perpetration of IPV. However, examining women’s alcohol use separate from the alcohol use of their male partners poses difficulties because of the associations between men’s and women’s drinking. That is, on average, men drink more than women (Keyes et al., 2008), resulting in many couples in which the husband but not the wife is a heavy or problematic drinker. In contrast, most heavy drinking women are married to heavy drinking men (Leonard and Eiden, 1999), making it difficult to isolate the effects of a woman’s alcohol use on her perpetration of IPV separate from the effects of her partner’s use.

Although it is typical to consider alcohol use as a precursor to one’s own perpetration of aggression (Ito et al., 1996), one partner’s alcohol use may also increase the likelihood that the other partner will perpetrate IPV. Several studies have shown an association between women’s alcohol use and experiencing victimization, that is, male-to-female IPV (Golinelli et al., 2009; Kantor and Asdigian, 1997; Lipsky et al., 2005). White and Chen (2002) also found an association between male partner problem drinking and female IPV perpetration; in fact, male partner drinking fully mediated the effect of female problem drinking on female IPV perpetration. A heavy drinking partner may increase relationship stress, thereby contributing to the other partner behaving aggressively (Leonard, 2000). There is also limited evidence suggesting that the interaction of husband and wife drinking may be important to consider. Longitudinal studies suggest that couples in which partners’ drinking patterns are discrepant experience greater declines in marital satisfaction compared with those with congruent drinking, even after controlling for heavy drinking (Homish and Leonard, 2005, 2007). Accordingly, discordant drinking has been associated with physical aggression after accounting for the effects of drinking level (Leadley et al., 2000).

Another important issue in examining the effect of alcohol use on IPV involves the type of alcohol measure used. Measures range from quantity and/or frequency of consumption to measures of alcohol problems, abuse, or dependence. Some have suggested that the effects of alcohol consumption are not linear, but rather are more consistent with a threshold effect, whereby only high or problematic levels are associated with the perpetration of IPV (Leonard, 2008; O’Leary and Schumacher, 2003). In their meta-analysis, Foran and O’Leary (2008) found that effect sizes were significantly larger for studies using measures of alcohol consequences compared with measures of alcohol consumption.

The current study was designed to examine the role of alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence symptoms in predicting husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband IPV within a community sample of couples. As noted above, examining the independent effects of women’s drinking poses challenges because of the relative rarity of couples in which the wife but not the husband is a heavy drinker. Consequently, in recruiting the current community sample, we deliberately oversampled couples in which (a) the wife but not the husband met criteria for heavy episodic drinking (HED), (b) the husband but not the wife met criteria for HED, and (c) both husband and wife met criteria for HED. We hypothesized that the alcohol dependence symptoms of each partner would contribute to the likelihood of husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband physical aggression. We also considered separately whether the alcohol consumption of each partner positively predicted both husband and wife IPV. Prior research suggests that alcohol dependence is likely to be a stronger contributor to IPV than consumption (Foran and O’Leary, 2008). Finally, we also considered the interaction between husband and wife alcohol consumption and husband and wife dependence symptoms, allowing us to determine whether a discrepancy between partners’ drinking increases the likelihood or frequency of physical aggression (Leadley et al., 2000).

Method

Participants

A community sample of couples (N = 280) was recruited via a mailed survey of health behaviors in the community. Using a list of residents that was developed by Survey Sampling International (Shelton, CT) and largely based on public phone records with information supplemented from other databases, we identified households in Erie County, NY, likely to contain a married couple between the ages of 18 and 45 years. We mailed 21,000 screening questionnaires to these households. The letter accompanying the questionnaire indicated that the purpose of the study was to help us estimate the number of different kinds of families and to determine eligibility and interest in participating in research on families and health. Based on a pilot study that indicated a 10% improvement in return rates (Homish and Leonard, 2009), we included a nonconditional $1 incentive in the questionnaire and provided a stamped envelope to return the questionnaire. We received 5,463 responses, for a 26% response rate (226, or about 1%, were returned because of an incorrect address). Of the 5,463 responses, 10.7% were minorities, with 7.6% being African American, similar to census data for married couples in Erie County (i.e., 90% White, 6% African American; U.S. Census Bureau, 2009).

The purpose of the mailed questionnaire was to assess eligibility criteria and to determine husband and wife HED status. Couples were eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 45 years and married or living together as married for at least 1 year. Because one aim of the study involved executive cognitive functioning, we excluded couples if either member had a current medical condition that would impair executive cognitive functioning or if either reported having had a seizure or epilepsy or a 10-minute loss of consciousness because of an accident or head injury. To ensure adequate numbers of heavy drinking husbands and wives, we used disproportionate sampling to recruit couples in which either the husband or the wife, both, or neither engaged in regular HED. HED was defined as engaging in at least weekly consumption of five or more drinks at one time for men (four drinks for women) or becoming intoxicated at least weekly. Our goal was to recruit 75 couples in each of four groups: (a) husband and wife both engaged in HED (Both), (b) only the husband engaged in HED (Husband Only), (c) only the wife engaged in HED (Wife Only), and (d) neither engaged in HED (Control).

Of the 5,463 responses, 3,477 met eligibility criteria. Of those meeting eligibility criteria, three quarters (75%) of the couples were Controls. The prevalence of Husband Only, Wife Only, and Both were 12.3%, 4.1%, and 8.5%, respectively. We also asked whether the couple was interested in participating in one of our ongoing studies, interested in hearing more about the study, or not at all interested. Across the four groups, 68% (N = 2,347) were interested in participating or hearing more about the studies. Surprisingly, the proportion of those who were interested was significantly higher for Husband Only (72%), Wife Only (74%), and Both (76%) than for Control (67%), χ2(3) = 16.32, p < .01. We sampled from the four groups at different rates to achieve the goal of 75 couples in each of the four groups. This disproportionate sampling was by design and has implications for our data analyses. We were able to recruit 80 Control, 80 Husband Only, 79 Both, and 41 Wife Only couples. This was a 43% success rate from those we attempted to recruit, a rate that did not differ across the four groups, χ2(3) = 2.78, p > .40. This indicates that the difficulty that we experienced filling the Wife Only cell reflected the rarity of this group in the population and not any difference in willingness to participate among these couples.

The average age of the final sample was similar between husbands and wives (36.9 years, SD = 5.8, and 35.4, SD = 5.9, respectively). The majority of men and women in the sample were White (91% each). They were well educated (58% of husbands and 67% of wives had completed a college education compared with 39% for the county), and most were employed at least part time (91% of husbands and 80% of wives). The majority of couples were married (87%) as opposed to cohabiting, for an average of 9.84 years (SD = 5.41). Approximately 79% had children. Among those with children, 15% had one child, 38% had two, 19% had three, and 7.5% had four or more children. The median income for wives was in the $20,000–$29,999 range, and the median income for husbands was in the $40,000–$54,999 range, making the median household income somewhat higher than that for the county ($52,000).

Procedure

Participants provided written informed consent to participate in the research. Before attending a laboratory assessment, each partner independently completed a series of questionnaires sent and returned through the mail. Mailed questionnaires, sent separately to the husband and wife, consisted of background information, attitudes and beliefs about alcohol, and personality measures. These measures were included in the mailed questionnaires because they were not particularly sensitive for the participants to answer and hence were unlikely to precipitate marital conflicts. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaires independently and not to discuss the questionnaires until both had been returned. After return of the questionnaires, couples were scheduled for an in-person assessment. At this laboratory assessment, partners independently completed computerized questionnaires that addressed relationship issues and alcohol and drug use. In addition, we administered measures of executive cognitive functioning and conducted a semistructured face-to-face interview regarding one or more episodes of conflict. Participants were assured that their responses were confidential and would not be shared with their partners. Only measures relevant to the present analyses are described below.

Measures

Intimate partner violence.

Husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV over the past 12 months was assessed using the physical aggression subscales of the revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996). Each partner reported on the frequency of 12 aggressive acts perpetrated by him/herself (e.g., “I slapped my partner”) and the same 12 acts as perpetrated by his/her partner (“my partner slapped me”). The frequency of each act was recorded using the following scale: never (0), once (1), twice (2), 3–5 times (3), 6–10 times (4), 11–20 times (5), and more than 20 times (6). Following standard scoring procedures (Straus et al., 1996), these values were converted to the number of acts based on the midpoints of each category: 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, and 25. The number of acts was then summed to create separate perpetration and victimization subscales, as reported by the husband and wife. Because severe violence perpetration and victimization were rarely reported, we opted to combine minor and severe physical aggression items to create a single IPV score. As expected, the CTS2 scores were positively skewed. To reduce skewness, outliers were Winsorized by recoding extremely high values to the next highest value in the distribution (Reifman and Keyton, 2010).

Alcohol consumption.

Respondents were asked about their typical quantity and frequency of consumption of beer, wine, and distilled spirits over the past 12 months. First, for each type of drink, the respondent reported the frequency of consumption using a 9-point scale ranging from not at all (0) to every day (9). We used the beverage with the highest frequency score as a measure of frequency of consumption. For each beverage consumed, the respondent indicated the typical quantity of consumption, using a 10-point scale ranging from 1 drink to 18 or more drinks. We used the highest typical number of drinks reported, whether for beer, wine, or distilled spirits, as a measure of quantity.

Alcohol dependence.

The 25-item Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner and Horn, 1984) was used to assess self-reported occurrence of symptoms such as blackouts and seeing things that were not really there. As expected, the distribution of ADS scores was highly skewed, with 41.9% of men and 55.2% of women reporting ADS scores of 0 but just 4.7% of men and 1.9% of women scoring greater than 9. Scores were Winsorized to reduce the impact of extremely high scores.

Demographics.

Information collected from each partner included age, race, years married and/or years living together, number of children living in the home, and education. Partner reports of age (r = .83), total years living together (r = .96), and number of children living in the home (r = .97) were highly correlated. To reduce the number of control variables in the analyses, we used the maximum report of the number of children (coded as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or more) and years together and the average couple age. Husband and wife education (r = .53) were entered separately as control variables. Because the vast majority of couples were White and married, we did not use race or marital status as covariates.

Results

Agreement between partner reports of intimate partner violence

Using continuous CTS2 scores, there were no differences in husband (M = 1.09, SD = 3.29) versus wife (M = 0.92, SD = 2.52) reports of wife-perpetrated IPV, t(279) = .94, p = .35. Nor were there differences in husband (M = 0.56, SD = 2.02) versus wife (M = 0.72, SD = 2.55) reports of husband-perpetrated IPV, t(279) = -.92, p = .36. Husband and wife reports of wife-perpetrated IPV were significantly but modestly correlated (r = .43, p < .001), as were husband and wife reports of husband-perpetrated IPV (r = .28, p < .001).

Collapsing CTS2 subscales to determine whether any IPV was reported, 191 partners agreed that there was no wife-perpetrated IPV, 43 agreed that there was wife-perpetrated IPV, and 25 women and 21 men reported wife-perpetrated IPV that was not corroborated by the partner. Similarly, 216 couples agreed that there was no husband-perpetrated IPV, 24 agreed that there was husband-perpetrated IPV, and 22 wives and 18 husbands reported husband-perpetrated IPV that was not corroborated by the partner. Previous research has suggested that women are more likely to report IPV than men and that victims are more likely to report IPV than perpetrators (Archer, 1999; Heyman and Schlee, 1997; Schafer et al., 2002). To test whether the proportion of husbands reporting wife-perpetrated IPV differed from the proportion of wives reporting wife-perpetrated IPV, we used McNemar’s test. This test was not significant, χ2(1) = 0.196, p = .66, indicating that husbands and wives were equally likely to report wife-to-husband IPV. Likewise, there was no bias in the proportion of husbands versus wives reporting versus not reporting husband-to-wife IPV, χ2(1) = 0.23, p = .64. Because of the absence of systematic bias in partner reports and a desire to minimize underreporting thought to occur with IPV, all subsequent analyses use the maximum report of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV, regardless of whether it was reported for self or for partner.

Association between husband- and wife-perpetrated intimate partner violence and alcohol measures

As shown in Table 1, husband and wife alcohol variables were generally positively correlated, within respondent and within couple. As expected, husbands reported higher quantity, frequency, and ADS scores compared with their wives (all ps < .01). Also as expected, husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV were significantly correlated (r = .61, p < .001), with the high correlation reflecting that the majority of couples reported no IPV over the past year. A paired sample t test comparing husband-perpetrated and wife-perpetrated IPV within couples revealed higher wife (M = 1.55, SD = 3.72) compared with husband (M = 1.04, SD = 2.98) CTS2 perpetration scores, t(279) = 2.77, p = .006. A comparison of the proportion of husbands who perpetrated IPV with the proportion of wives who perpetrated IPV revealed a similar pattern. That is, although the majority of couples included partners who were both nonviolent (N = 182) or engaged in mutual violence (N = 55), McNemar’s test revealed that couples with wife- but not husband-perpetrated IPV (N= 34) were more common than the reverse (N= 9), χ2(1) = 13.40, p < .001. Because of the high within-couple correspondence in IPV perpetration, analyses were conducted without controlling for perpetration by the other partner.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations among husband and wife alcohol variables and IPV

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | M (SD) | |

| 1. H frequency | 0.41 (0.32) | |||||||

| 2. H quantity | .123* | 5.35 (4.00) | ||||||

| 3. H ADS | .434*** | .482*** | 3.83 (3.94) | |||||

| 4. H-to-W IPV | -.010 | .169** | .172** | 1.04(2.98) | ||||

| 5. W frequency | .368*** | .033 | .153* | .106 | 0.27 (0.29) | |||

| 6. W quantity | .026 | .271** | .102 | .178** | .317*** | 3.61 (3.21) | ||

| 7. W ADS | .154* | .236*** | .257*** | .473*** | .454*** | .473*** | 2.76 (3.43) | |

| 8. W-to-H IPV | -.097 | .093 | .032 | .606*** | .108 | .106 | .213*** | 1.55(3.72) |

Notes: Using unweighted data. IPV = intimate partner violence; H = husband; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale; W = wife.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Analysis plan

Substantive analyses considered the impact of husband and wife ADS scores and alcohol consumption on both perpetration of any IPV and on the frequency of IPV occurrence, using continuous CTS2 scores. Because the frequency of consumption was not correlated with IPV (Table 1), we focused on quantity rather than frequency of consumption as a predictor. Because our analyses used continuous measures of alcohol consumption and dependence symptoms rather than specific groups, we took into account the disproportionate sampling of the couple drinking groups by weighting the different groups to reflect their prevalence among the eligible respondents to our mailed survey. This use of weights is common when simple random sampling has not been used and minimizes the potential of bias (Korn and Graubard, 1995; Pfeffermann, 1993). Analyses using weighted data were conducted separately for husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband IPV.

Predicting the occurrence of intimate partner violence

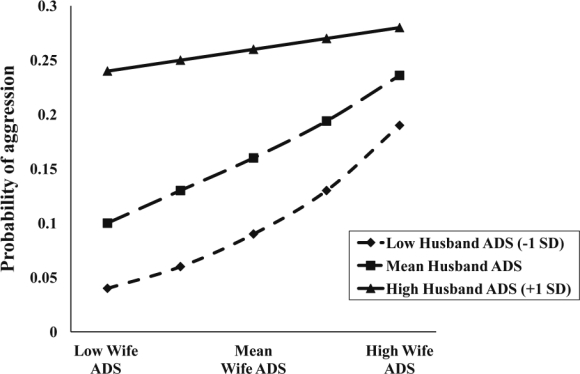

In the first set of analyses, blockwise logistic regression was used to examine the impact of ADS scores on the occurrence of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV. We entered control variables (age, years together, number of children, and husband and wife education) and husband and wife ADS on the first step, followed by the interaction of husband and wife ADS on the second step. The results are shown in Table 2. In the equation predicting wife-perpetrated IPV, higher husband ADS scores significantly increased the odds of IPV; wife ADS was marginally significant (p = .06). For husband-perpetrated IPV, both husband ADS and wife ADS predicted the occurrence of aggression; however, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction between husband and wife ADS. The nature of the interaction, depicted in Figure 1, reveals that when wife ADS was at the mean or below, there was a steep increase in the odds of husband-perpetrated IPV associated with increasing husband ADS. In contrast, when the wife’s ADS was high, the odds of husband-perpetrated IPV were high at all levels of husband ADS; that is, husband ADS did not increase the probability of his aggression.

Table 2.

Hierarchical logistic regression predicting occurrence of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV from alcohol dependence symptoms

| Variable | Husband-perpetrated IPV |

Wife-perpetrated IPV |

||||||

| χ2 | Initial OR | Final OR | [Final CI, 95%] | χ2 | Initial OR | Final OR | [Final CI, 95%] | |

| Step 1 | 42.27*** | 29.05*** | ||||||

| Age | 0.99 | 1.00 | [0.92, 1.08] | 0.97 | 0.97 | [0.90, 1.04] | ||

| No. of children | 0.80 | 0.81 | [0.59, 1.10] | 1.11 | 1.11 | [0.84, 1.47] | ||

| Years together | 1.01 | 1.00 | [0.92, 1.09] | 0.97 | 0.97 | [0.90, 1.05] | ||

| Wife education | 0.71** | 0.71** | [0.56, 0.91] | 0.77* | 0.77* | [0.63, 0.94] | ||

| Husband education | 1.28 | 1.28 | [0.99, 1.64] | 1.13 | 1.13 | [0.91, 1.39] | ||

| Wife ADS | 1.15* | 1.23** | [1.09, 1.40] | 1.11 | 1.14* | [1.02, 1.28] | ||

| Husband ADS | 1.20*** | 1.24*** | [1.12, 1.38] | 1.14** | 1.16** | [1.06, 1.27] | ||

| Step 2 | 6.21* | 1.86 | ||||||

| Wife ADS × Husband ADS | 0.74* | [0.58, 0.94] | 0.86 | [0.69, 1.07] | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .257 | .153 | ||||||

Notes: IPV = intimate partner violence; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

The probability of the occurrence of husband-to-wife aggression as a function of husband and wife Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) scores

The above blockwise logistic regression analyses were then repeated using the quantity of husband and wife alcohol consumption instead of ADS scores as predictors of the occurrence of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV. The results (not shown) revealed that the husband’s alcohol quantity was the only significant predictor of husband IPV (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16, CI [1.07, 1.28], p < .001) and wife IPV (OR = 1.09, CI [1.01, 1.18], p < .05). The interaction was not significant in either equation.

Predicting the frequency of intimate partner violence

We also considered whether husband and wife alcohol use predict the frequency of husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband aggression. Because these outcomes are count variables (the number of physically aggressive acts) with a positively skewed distribution, a Poisson family can be specified in analyzing such data. However, because Poisson models have restrictive assumptions that can be easily violated, resulting in misleading results, negative binomial models have been advocated as a more appropriate choice (Byers et al., 2003; Gardner et al., 1995). Thus, negative binomial regression, with Stata (version MP 11.2; StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX) was used in models predicting the frequency of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV.

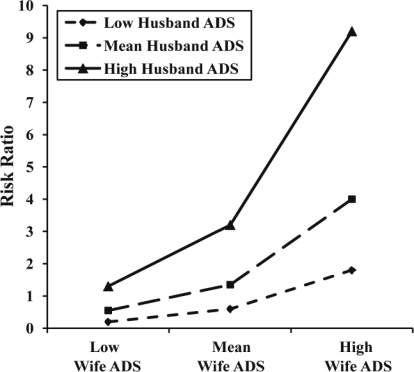

Table 3 presents risk ratios for the main effects model followed by the full model, including the Husband × Wife ADS interaction term. Risk ratios greater than 1 represent an increased risk; risk ratios less than 1 a decreased risk. For the frequency of husband IPV, the pattern of findings for husband and wife ADS was identical to the logistic regression results presented above. That is, there were significant main effects for husband and wife ADS as well as a significant interaction. However, the nature of this interaction, depicted in Figure 2, differed from the logistic interaction. That is, the combination of high husband and wife ADS led to especially large increases in the frequency of husband-perpetrated aggression. For the frequency of wife-perpetrated aggression, both husband and wife ADS contributed independently to the frequency of aggression; however, their interaction was not significant.

Table 3.

Negative binomial regression predicting frequency of husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV from alcohol dependence symptoms

| Variable | Husband-perpetrated IPV |

Wife-perpetrated IPV |

||||||

| Main effects model |

Interaction model |

Main effects model |

Interaction model |

|||||

| RR | [95% CI] | RR | [95%CI] | RR | [95% CI] | RR | [95%CI] | |

| Age | 1.11 | [0.99, 1.24] | 1.11 | [0.99, 1.25] | 1.04 | [0.95, 1.13] | 1.04 | [0.95, 1.13] |

| No. of children | 0.55** | [0.36, 0.84] | 0.58** | [0.39, 0.87] | 0.84 | [0.57, 1.25] | 0.86 | [0.58, 1.27] |

| Years together | 1.00 | [0.89, 1.12] | 0.99 | [0.89, 1.11] | 1.03 | [0.94, 1.14] | 1.02 | [0.93, 1.13] |

| Wife education | 0.63*** | [0.48, 0.83] | 0.63** | [0.48, 0.83] | 0.59*** | [0.46, 0.76] | 0.59*** | [0.46, 0.77] |

| Husband education | 1.37* | [1.00, 1.88] | 1.27 | [0.92, 1.75] | 1.49** | [1.15, 1.92] | 1.45** | [1.12, 1.87] |

| Wife ADS | 1.29*** | [1.12, 1.47] | 1.38*** | [1.15, 1.66] | 1.16*** | [1.07, 1.26] | 1.19*** | [1.08, 1.31] |

| Husband ADS | 1 20*** | [1.08, 1.33] | 1.24*** | [1.11, 1.38] | 1.11* | [1.00, 1.22] | 1.12* | [1.01, 1.25] |

| Wife ADS × Husband ADS | 0.74** | [0.59, 0.91] | 0.87 | [0.74, 1.04] | ||||

Notes: IPV = intimate partner violence; RR = risk ratio; CI = confidence interval; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Risk ratio for husband-to-wife aggression as a function of husband and wife Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) scores

Negative binomial regression was also used to examine whether the quantity of husband or wife alcohol consumption predicts the frequency of aggression (not shown). For husband-perpetrated IPV, the husband quantity was the only predictor that was significant (risk ratio = 1.15, CI [1.05, 1.25], p < .01). For wife-perpetrated IPV, neither the husband nor wife quantity nor their interaction predicted the frequency of occurrence.

Discussion

The current study considered the combined impact of husbands’ and wives’ drinking on husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband IPV in a community sample. By oversampling couples containing heavy episodic drinkers, we were able to examine the role of women’s drinking on IPV with more precision than has typically been the case. Although research has firmly established the relationship between male drinking and male-to-female partner violence, findings with respect to female drinking and female-to-male violence have been more equivocal, particularly in general population samples. Such samples usually include very few heavy drinking women, and even fewer heavy drinking women married to lighter drinking men. As a consequence, estimates of the effect of women’s heavy drinking may be heavily dependent on a small number of observations. For example, even in one of the largest general population samples of couples to date (Leadley et al., 2000), out of more than 1,600 couples, there were only 18 couples in which both the husband and wife engaged in HED and 27 couples in which the wife, but not the husband, engaged in HED. We examined the relationship with a substantially larger sample of heavy drinking women (n = 120).

Results predicting husband aggression generally support prior research in showing that husbands’ and wives’ ADS scores were independently and interactively associated with both the occurrence and frequency of husband-perpetrated IPV. However, the nature of these interactions differed. The interaction that emerged in prediction of the occurrence of husband aggression suggests that a high ADS score in either the husband or the wife increases the likelihood of IPV, but high ADS scores by both do not lead to a further increase in the likelihood of husband perpetration. The findings are consistent with the notion that there are a limited number of individuals who are at risk for partner aggression and that the threshold for the occurrence of any husband aggression can be reached by either husband or wife heavy drinking. In contrast, in the equation predicting the frequency of husband-to-wife aggression, the nature of the interaction between husband and wife ADS suggested an exacerbation in the increased frequency of aggression when both partners had high ADS scores. The differential implications of the occurrence versus frequency analyses are crucial to understand. Although the heavy drinking of the wife, for example, may not increase the likelihood of one episode of aggression if her husband is also a heavy drinker, it may increase the likelihood of multiple episodes. The importance of this with respect to clinical issues is readily apparent: in a heavy drinking couple, reducing one partner’s drinking may not eliminate all occurrences of violence, but it may lead to fewer occurrences. This also raises the possibility that processes linking drinking patterns and violence may differ in terms of crossing the threshold to becoming physically aggressive and the occurrence of frequent or severe violence, a possibility discussed by O’Leary (1993).

The results for the prediction of wife-perpetrated aggression support a somewhat weaker role of alcohol. In equations predicting the occurrence of any wife-perpetrated aggression, husband ADS and alcohol quantity significantly increased the odds of occurrence, whereas neither wife quantity nor wife ADS were significant. These findings suggest that women’s drinking is not a critical trigger for their perpetration of IPV, a conclusion that is consistent with experimental studies on alcohol and perpetration of aggression in the laboratory, in which men’s but not women’s aggression is increased following administration of alcohol (Giancola et al., 2002, 2009). Because women’s aggression has a lower potential for physical harm than men’s, women may be less inhibited in expressing at least low levels of aggression (Cross et al., 2011). Women in this sample perpetrated IPV at a higher rate than their husbands, a finding consistent with several previous studies of community samples (O’Leary et al., 1989; Schumacher and Leonard, 2005). Consequently, the occurrence of female physical aggression may not be easily predictable from the woman’s own characteristics (Magdol et al., 1997) but rather may reflect any number of different situational or partner-based provocations (including a heavy drinking partner). On the other hand, once the threshold of perpetration has been crossed, both wife and husband ADS contribute to the frequency of wife aggression.

Several additional aspects of the results warrant consideration. First, the pattern of results for ADS scores versus quantity of consumption differed somewhat. Our findings are generally consistent with previous research suggesting that it is heavy episodic or problematic drinking that is particularly associated with men’s perpetration of IPV toward their partners (Leonard, 2008; Leonard et al., 1985; O’Leary and Schumacher, 2003). Effect sizes for measures of consumption are typically smaller than those for alcohol problems (Foran and O’Leary, 2008). Although men’s quantity of consumption was positively associated with the occurrence of both husband- and wife-perpetrated IPV and the frequency of husband (but not wife) IPV, women’s quantity was not associated with husband or wife IPV in any of the analyses. Previous research has also concluded that alcohol is a stronger predictor of male as opposed to female IPV (Foran and O’Leary, 2008). We recruited a substantial number of heavy drinking women, but the drinking quantities of these women were still substantially less than those of their male partners and may be insufficient to trigger aggression by either partner.

Although our findings provide additional evidence that one’s own drinking as well as the drinking of one’s partner contribute to the likelihood of perpetration of IPV (White and Chen, 2002), results failed to support the hypothesis that discrepant drinking patterns increase either the odds or the frequency of IPV perpetration. A growing body of research has documented the negative effects of discrepant drinking patterns on marital satisfaction (Homish and Leonard, 2005, 2007), but low satisfaction does not necessarily lead to IPV (Baker and Stith, 2008; Testa et al., 2011). Given the association between low relationship satisfaction and relationship dissolution (Karney and Bradbury, 1995), couples in which drinking discrepancy was most problematic may not have been included, given that this was a sample of intact couples.

We note several limitations. First, analyses were deliberately limited to examining the direct relationship of alcohol use to the perpetration of IPV. It is possible that alcohol dependence or consumption plays an indirect or moderated role in the perpetration of IPV or that the association is spurious, reflecting the effects of a common third variable. Subsequent analyses are planned to consider these possibilities. In addition, although our deliberate sampling resulted in a substantial proportion of heavy drinking men and women, the sample size was still relatively modest and may not generalize to other geographic areas or samples. Although demographic characteristics of our sample matched those of the county fairly well, it is likely that our method of recruitment resulted in omission of couples without stable addresses and those with the highest levels of marital violence or problems with alcohol. Finally, it is important to remember that these are not event-level analyses; hence, although results indicate that heavy drinkers were more likely to perpetrate aggression, we do not know whether aggression occurred while couples were drinking alcohol. Nonetheless, the current study provides further evidence that in community samples of couples, husband and wife alcohol dependence symptoms are predictive of both husband-to-wife IPV and, to a lesser extent, wife-to-husband IPV. More refined research focusing on the processes that link distal drinking habits or problems to instances of partner violence is needed.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA016829 (to Kenneth E. Leonard).

References

- Archer J. Assessment of the reliability of the conflict tactics scales: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Baker CR, Stith SM. Factors predicting dating violence perpetration among male and female college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2008;17:227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Allore H, Gill TM, Peduzzi PN. Application of negative binomial modeling for discrete outcomes: A case study in aging research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56:559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross CP, Tee W, Campbell A. Gender symmetry in intimate aggression: An effect of intimacy or target sex? Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:268–277. doi: 10.1002/ab.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Helton EL, Osborne AB, Terry MK, Fuss AM, Westerfield JA. The effects of alcohol and provocation on aggressive behavior in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Levinson CA, Corman MD, Godlaski AJ, Morris DH, Phillips JP, Holt JC. Men and women, alcohol and aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0016385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli D, Longshore D, Wenzel SL. Substance use and intimate partner violence: Clarifying the relevance of women’s use and partners’ use. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2009;36:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Schlee KA. Toward a better estimate of the prevalence of partner abuse: Adjusting rates based on the sensitivity of the Conflict Tactics Scale. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:488–496. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. Testing methodologies to recruit adult drug-using couples. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Miller N, Pollock VE. Alcohol and aggression: A meta-analysis on the moderating effects of inhibitory cues, triggering events, and self-focused attention. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:60–82. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK, Asdigian N. When women are under the influence. Does drinking or drug use by women provoke beatings by men? Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1997;13:315–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK, Straus MA. Substance abuse as a precipitant of wife abuse victimizations. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1989;15:173–189. doi: 10.3109/00952998909092719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI. Examples of differing weighted and unweighted estimates from a sample survey. The American Statistician. 1995;49:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Taliaferro E, Stone S, Tubb T, Linden JA, Krauss JE. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1892–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley K, Clark CL, Caetano R. Couples’ drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, K.E. (2000). Domestic violence and alcohol: What is known and what do we need to know to encourage environmental interventions? Paper presented at Alcohol Policy 12 Conference, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Alcohol and violence: Exploring patterns and responses. Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies; 2008. The role of drinking patterns and acute intoxication in violent interpersonal behaviors; pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Day NL, Ryan CM. Patterns of alcohol use and physically aggressive behavior in men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1985;46:279–282. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Husbands’ and wives’ drinking: Unilateral or bilateral influences among newlyweds in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 1999;13:130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? A synthesis of evidence. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 245–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Caetano R, Field CA, Larkin GL. Psychosocial and substance-use risk factors for intimate partner violence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M, Murphy CM. Partner violence before and after individually based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:92–102. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Through a psychological lens. Personality traits, personality disorders, and levels of violence. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DR, editors. Current controversies on family violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Barling J, Arias I, Rosenbaum A, Malone J, Tyree A. Prevalence and stability of physical aggression between spouses: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:263–268. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Schumacher JA. The association between alcohol use and intimate partner violence: Linear effect, threshold effect, or both? Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffermann D. The role of sampling weights when modeling survey data. International Statistical Review. 1993;61:317–337. [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Keyton K. Winsorize. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. pp. 1636–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Agreement about violence in U.S. couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:457–470. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale: Users guide. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48:465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Leonard KE. Female intimate partner violence perpetration: Stability and predictors of mutual and nonmutual aggression across the first year of college. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:362–373. doi: 10.1002/ab.20391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2009. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/ servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-context=st&-qr_name=ACS_2009_5YR_ G00_S 1201 &-ds_name=ACS_2009_5 YR_G00_&-CONTEXT=st&-tree_id=5309&-redoLog=true&-geo_id=05000US36029&-format=&-_lang=en.

- White HR, Chen P-H. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]