Abstract

Manipulation of various components of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response (ERSR) has led to functional recovery in diabetes, cancer, and several neurodegenerative diseases, indicating its use as a potential therapeutic intervention. One of the downstream pro-apoptotic transcription factors activated by the ERSR is CCAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP). Recently, we showed significant recovery in hindlimb locomotion function after moderate contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) in mice null for CHOP. However, more than 40% of human SCI are complete. Thus the present study examined the potential therapeutic modulation of CHOP in a more severe SCI injury. Contused wild-type spinal cords showed a rapid activation of PERK, ATF6, and IRE-1, the three arms of the ERSR signaling pathway, specifically at the injury epicenter. Confocal images of phosphorylated EIF2α, GRP78, CHOP, ATF4, and GADD34 localized the activation of the ERSR in neurons and oligodendrocytes at the injury epicenter. To directly determine the role of CHOP, wild-type and CHOP-null mice with severe contusive SCI were analyzed for improvement in hindlimb locomotion. Despite the loss of CHOP, the other effectors in the ERSR pathway were significantly increased beyond that observed previously with moderate injury. Concomitantly, Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) scores and white matter sparing between the wild-type and CHOP-null mice revealed no significant differences. Given the complex pathophysiology of severe SCI, ablation of CHOP alone is not sufficient to rescue functional deficits. These data raise the caution that injury severity may be a key variable in attempting to translate preclinical therapies to clinical practice.

Key words: CHOP, contusion, endoplasmic reticulum stress, spinal cord injury

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response (ERSR)/unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated to maintain protein homeostasis in the ER in response to distinct cellular insults, including hypoxia, ischemia, trauma, and oxidative damage. The signaling cascade of the ERSR involves three transmembrane proteins that respond to the protein folding stress of the ER: ER stress-activated protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like kinase (PERK), inositol requiring protein-1α (IRE-1α), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6; Rutkowski and Kaufman, 2007). Initial activation of the ERSR is cytoprotective, resulting in reduced translation, enhanced ER protein folding capacity, and clearance of misfolded ER proteins to restore ER function (Boyce and Yuan, 2006). Prolonged ERSR, due to an inability of the cell to restore ER function, leads to an imbalance in the signaling cascade, and switches on ERSR-activated apoptosis (Ferri and Kroemer, 2001; Oyadomari et al., 2002). The contribution of UPR-activated cell death has been reported in ischemic stroke (Lange et al., 2008), multiple sclerosis (Lin et al., 2006), and Alzheimer's disease (Milhavet et al., 2002). One of the major effectors of the ER-stress-mediated apoptotic pathway is the transcription factor, CCAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP; Ron and Habener, 1992).

No single clinical therapy significantly increases functional recovery after SCI in all injury groups. Methylprednisolone and ganglioside GM1 have shown modest efficacy in subsets of human SCI patients, although these data remain controversial (Hawryluk et al., 2008). We recently demonstrated activation of the ERSR in a moderate T9 contusion model of SCI, and significant functional recovery in the hindlimb locomotion of CHOP-null mice. That functional recovery correlated with an increase in white matter sparing and transcript levels of myelin basic protein (MBP) and claudin 11 (Ohri et al., 2011). Similarly, a previous study demonstrated ERSR activation in rats after moderate contusive SCI (Penas et al., 2007). As more than 40% of human SCI are complete and thus defined as severe (www.nscisc.uab.edu), the purpose of this study was to determine if modulation of the ERSR in a severe SCI can also enhance functional recovery.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, 1996), and with the approval of the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CHOP-null mice, completely bred to a 100% C57BL/6 background, were procured from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Age- and weight-matched wild-type C57BL/6 female mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN).

Spinal cord injury

Mice were anesthetized by an IP injection of 0.4 mg/g body weight Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol in 0.02 mL of 1.25% 2-methyl-2-butanol in saline; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Lacri-Lube ophthalmic ointment (Allergen, Irvine, CA) was used to prevent drying of eyes, and gentamicin (50 mg/kg; Boehringer Ingelheim, St. Joseph, MO) was subcutaneously administered to reduce infection. A laminectomy was done at the T9 vertebra and the mice were placed in a custom stabilizer device, which holds the spinal cord level and steady in the Louisville Injury Systems Apparatus (LISA) as described previously (Beare et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2008). The LISA uses a laser sensor to measure the velocity and displacement of an injury is obtained by an impactor. Both wild-type and CHOP-null mice received a 0.45-mm-displacement contusion at a velocity of 1.0 m/sec. This injury was predicted to be moderate/severe, but because of new clamps produced a reproducible severe injury as defined by both the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) and white matter sparing. Injury severity, based on the biophysical parameters of impactor movement, was identical for all animals. Experimental controls included sham animals that remained uncontused and received laminectomy only at the T9 vertebra. Post-surgery, the animals were given 1 cc of sterile saline subcutaneously, 0.1 cc of gentamicin intramuscularly on the day of surgery, and on days 3 and 5 post-surgery, and 0.1 cc buprenorphine subcutaneously on the day of surgery and for the next 2 days. The animals were placed on a heating pad until full recovery from anesthesia. Post-operative care included manual expression of the bladders twice a day for 7–10 days or until spontaneous voiding returned. The animals were sacrificed 6 weeks post-injury.

RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was extracted from spinal cord tissue of sham animals, injured wild-type (n=4), and CHOP-null mice (n=4) at the injury epicenter (3 mm), and 1 cm away from the injury epicenter for rostral segments (3 mm) using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was quantified by UV spectroscopy and RNA integrity was confirmed on an ethidium bromide-stained formaldehyde agarose gel. cDNA was synthesized with 1 μg of total RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a 20-μL reaction volume. As controls, mixtures containing all components except the RT were prepared and treated similarly. All cDNAs and control reactions were diluted 10× with water before using as a template for quantitative real time (qRT)-PCR.

Quantitative PCR analysis

qRT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7900HT real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, diluted cDNAs were added to Taqman universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and run in triplicate. Target and reference gene PCR amplification was performed in separate tubes with Assay on Demand™ primers (Applied Biosystems) as follows: XBP1 (Mm00457359_m1), GRP78 (Mm01333323_g1), CHOP (Mm01135937_g1), ATF4 (Mm00515324_m1), and growth arrest and DNA-damage protein 34 (GADD34; mm00492555_m1). The RNA levels were quantified using the ΔΔCT method. Expression values obtained from triplicate runs of each cDNA sample were normalized to triplicate value for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; reference gene) from the same cDNA preparation. Transcript levels are expressed as fold changes compared with respective levels in sham controls.

XBP1 splicing

XBP1 splicing was performed using HotStarTaq enzyme (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 50 μL containing 2 μL of cDNA and 10 pmol of XBP1 primers (sense: ggccttgtggttga gaaccaggag; antisense, gaatgcccaaaaggatatcagactc) in 1× reaction buffer. Amplification cycles were: 94°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec, 68°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec. The final incubation was done at 72°C for 10 min. GAPDH transcript levels were used to normalize against different amounts of input RNA. XBP1 and GAPDH PCR products were resolved on 2.5% and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively, and detected by ethidium bromide staining.

Immunohistochemical analyses

Mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with ice cold PBS. The spinal cords were dissected fresh at different time intervals post-SCI and cryopreserved at −80°C. TBS™ was used as a mounting medium and the cords were sectioned longitudinally at 20 μm and stored at −80°C until further use. For immunostaining, spinal cord sections were post-fixed with ice cold methanol for 10 min and blocked in TBS containing 5% BSA and 0.1% Triton-X-100 for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Mouse polyclonal anti-NeuN (1:100; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), goat polyclonal anti-Olig2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and mouse monoclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:250; Chemicon) primary antibodies were used for neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes, respectively. The ER stress primary antibodies used were as follows: Rabbit polyclonal CHOP (1:100; Sigma, Ronkonkoma, NY), rabbit polyclonal ATF4 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal peIF2α (1:100; Biosource, Camarillo, CA), rabbit polyclonal GRP78 (1:250; Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI), and rabbit polyclonal GADD34 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The sections were then incubated with fluorescein- (1:100; FITC) and rhodamine (1:200; TRITC)-conjugated F(ab’)2 secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. Confocal images were obtained using an Eclipse 90i laser confocal microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Negative controls used were species-specific, non-immune IgGs or sera.

Western blot analyses

Protein lysates prepared from 0.4 cm tissue isolated from sham animals and the injury epicenter of contused cords at 6 h and 24 h post-injury in protein lysis solution (20 mm Tris, pH-6.8, 137 mm NaCl, 25 mm B-glycerophosphate, 2 mm NaPPi, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitor, 0.5 mm DTT, and 1 mm PMSF) were quantified using a BCA Kit (Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL). Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman, Schleicher & Schuell, London, U.K.). The membranes were processed using standard procedures with the following antibodies: GRP78 (1/1000 dilution; Cell Signaling, Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA), GADD34 (1/500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ATF4/CREB-2 (1/500 dilution), phospho-eIf2α (1/1000 dilution; Cell Signaling), eIF2α (1/1000; Biosource International, Wilmington, NC), and GAPDH (1/5000).

Behavioral assessment

Open field BMS locomotor analyses were performed prior to injury for each animal to determine the baseline scores, and weekly following SCI for 6 weeks exactly as defined by Basso and associates (2006). All raters were trained by Dr. Basso and colleagues at the Ohio State University and were blinded to animal groups.

White matter sparing

Six weeks after SCI, wild-type and CHOP-null mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and spinal cords at the injury epicenter±2 mm were dissected out and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. The next day the cords were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose and kept for at least 3 days at 4°C. TBS™ was used as the mounting medium and the cords were sectioned transversely at 20 μm and stored at −80°C until further use. Eriochrome cyanine (EC) was used to stain myelin to detect the extent of spared white matter at the injury epicenter. The percentage of spared white matter was determined with reference to sham control animals as described previously (Magnuson et al., 2005). Briefly, the slides were allowed to thaw at room temperature for an hour. The sections were then hydrated by submerging in Coppin jars containing xylene and ethanol in the following order: xylene (2×30 min), 100% ethanol (3 min), 95% ethanol (3 min), 70% ethanol (3 min), 50% ethanol (3 min), and distilled water (2 min), followed by staining in EC for 10 min. After dipping the sections in tap water twice to remove excess stain, the sections were differentiated in 0.5% ammonium hydroxide solution for 10 sec, and then underwent another two washes in tap water to stop the differentiation process. The sections were air dried overnight in a biological safely hood at room temperature, mounted the next day using mounting medium, and allowed to dry overnight in the hood. Images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope, and white matter was traced using Nikon Elements software. The epicenter was defined by the segment with the least amount of spared white matter.

Statistical analyses

For functional assessments after injury, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with fixed-effects and Bonferroni post-hoc t-test was performed to detect differences in BMS scores and subscores between the sham and injury groups over the 6-week testing period. Statistical analysis of qRT-PCR data was performed using the independent t-test for means with equal or unequal variances or repeated-measures ANOVA (one-way or two-way analysis of variance) followed by post-hoc Tukey HSD test. For all other analyses, the independent t-test for means assuming equal variance was performed.

Results

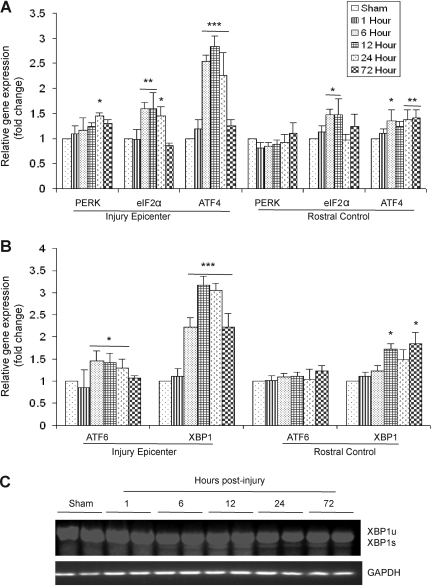

The ERSR pathway is executed by three ER transmembrane proteins: PERK, ATF6, and IRE-1α. The activation of the PERK arm of ERSR involves phosphorylation of eIF2α at Ser-51, which results in global shutdown of protein translation. Additionally, it also results in the increased expression of ATF4. Analysis of RNA isolated from the injury epicenter and rostral controls of wild-type animals at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 72 h post-severe SCI showed a significant upregulation of the ATF4 transcript levels to 2.5-fold at 6 h, threefold at 12 h, and 2.2-fold at 24 h by qRT-PCR. Upregulation of ATF4 was not observed in the rostral segments of mouse spinal cords, indicating the specificity of the ERSR to the injury epicenter (Fig. 1A). A significant 2.2- to 3.5-fold increase in XBP1 transcript levels at the injury epicenter occurred 6–72 h post-SCI (the latest time point tested), indicating the activation of the ATF6-dependent UPR signaling (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, a significant twofold increase in XBP1 mRNA levels was also observed at 12 h and 72 h in the rostral control segments of the lesioned cord, indicating a spread of the pathological process from the site of primary impact into the adjacent tissue. The presence of both the spliced (226-bp) and unspliced (254-bp) XBP1 transcripts at 6, 12, 24, and 72 h post-SCI compared to shams (laminectomy controls) by semi-quantitative PCR indicated the activation of the IRE-1α-dependent pathway of the ERSR (Yoshida et al., 2001; Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that severe injury to the spinal cord leads to a robust and early activation of all three arms of the ERSR.

FIG. 1.

Activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in T9 contused spinal cords of wild-type animals after severe spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) data show increased levels of protein kinase RNA-like kinase (PERK), eIF2α, and ATF4 in the injury epicenter and rostral control segments (normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]) expressed as fold changes and compared with levels in sham controls at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 72 h post-injury. (B) qRT-PCR of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and XBP1 transcript levels (normalized to GAPDH) expressed as fold changes compared with levels in sham controls at the injury epicenter and rostral controls suggest activation of the ATF6 arm of the UPR. (C) Representative agarose gel showing the presence of both spliced (XBP1s) and unspliced (XBP1u) transcript levels at 6, 12, 24, and 72 h post-SCI indicate activation of the IRE-1α arm. Data are the mean±standard deviation; n=4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

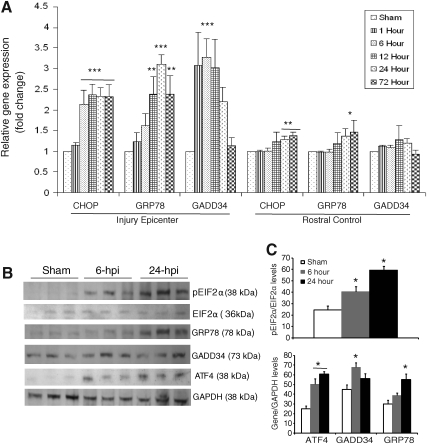

To gain further insight into the complex transcriptional response of downstream targets of the ERSR/UPR in response to severe SCI, we determined the expression level of CHOP, glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) and GADD34. qRT-PCR data demonstrated a significant 2.5-fold induction of CHOP mRNA as early as 6 h post-injury specifically at the injury epicenter. This induction persisted at least until 72 h (the latest time point examined). In addition, a significant increase in CHOP transcript levels was also apparent in rostral segments at 24 and 72 h post-injury, suggesting the spread of the UPR to adjacent tissue. This increase was not observed after moderate contusive SCI (Ohri et al., 2011). A significant 2.5- to 2.8-fold induction of GRP78 mRNA was observed at 12 h post-severe SCI, which increased to 3.2-fold at 24 h, and then decreased to 2.5- to 2.8-fold at 72 h. In contrast, the rostral segments did not show increased expression of GRP78 mRNA except at 72 h. The expression level of GADD34 mRNA increased to 3.5-fold as early as 1 h post-injury, persisted until 12 h, and then declined to basal levels by 72 h. Upregulation of GADD34 transcript levels was specific to the injury epicenter, as the rostral segments did not show any significant upregulation at any of the time points tested (Fig. 2A). To determine changes in the ERSR protein levels, protein lysates extracted from the epicenter of sham and contused animals after 6 and 24 h post-injury were analyzed on an immunoblot (Fig. 2B). An increase in phosphorylated EIF2α levels was evident at 6 h post-injury, which further increased at 24 h, indicating sustained translation attenuation. Levels of GRP78 were highest at 24 h post-injury, correlating with the qRT-PCR data. Increased levels of ATF4 were observed at 6 and 24 h post-injury. GADD34 protein levels were highest at 6 h post-injury. Collectively, these data indicate that the levels of various ERSR transcripts translate into corresponding alterations in protein levels.

FIG. 2.

Expression of the unfolded protein response (UPR) response genes in wild-type animals after severe spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Total RNA was extracted from spinal cords corresponding to the injury epicenter and rostral segments at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 72 h post-T9 contusion injury. Transcript levels of CCAAT enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), and growth arrest and DNA-damage protein 34 (GADD34) mRNAs were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and expressed as fold changes compared with levels in sham controls. Significant differences in expression levels of UPR mRNAs between the injury epicenter and rostral segments are indicated. Data are the mean±standard deviation (SD; n=4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (B) Immunoblots of protein lysates extracted from spinal cords of sham animals or the injury epicenter of contused animals at 6 and 24 h post-T9 injury with the indicated endoplasmic reticulum stress response (ERSR) markers. (C) Quantification of the Western blots in (B) reveals significant differences in the protein levels of ERSR markers as indicated. Data are the mean±SD (n=3, *p<0.05).

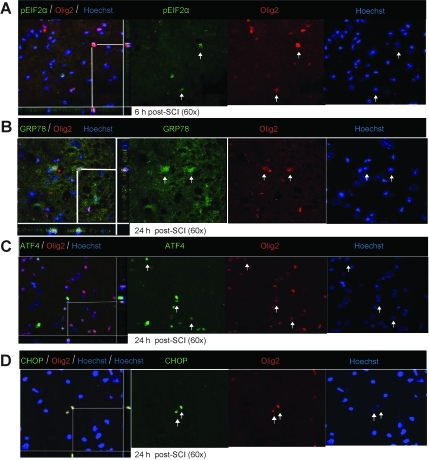

Immunohistochemical analyses showed the various key components of the UPR pathway to be co-localized in both neurons and oligodendrocytes. The accumulation of pEIF2α was apparent in both neurons (Fig. 3A) and oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A) at 6 h post-severe SCI. The expression of GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP was distinctly seen as early as 6 h post-severe SCI in neurons (Fig. 3B–D), and their oligodendrocytic expression was predominantly apparent at 24 h (Fig. 4B–D). In contrast, the non-injury controls did not show any detectable expression of these markers in either oligodendrocytes or neurons (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that traumatic severe injury to the spinal cord led to the increased expression of various ER stress response genes temporally in neurons and oligodendrocytes.

FIG. 3.

Expression of unfolded protein response (UPR) markers in neurons of wild-type animals after severe spinal cord injury (SCI). Immunohistochemical analyses of longitudinal sections reveal co-localization of pEIF2α (A) Glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), endoplasmic reticulum stress response (ERSR), activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4; C), and CCAAT enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP; D) with NeuN, a neuron-specific marker, at the injury epicenter at the indicated time points after severe SCI. Arrows indicate the individual co-localized cells that are identified in the XZ and YZ planes of the merged images (scale bar=50 μm). Identical data were observed in three independent experiments.

FIG. 4.

Oligodendrocytic expression of unfolded protein response (UPR) markers in wild-type animals after severe spinal cord injury (SCI). Immunohistochemical analyses of longitudinal sections reveal co-localization of pEIF2α (A), activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4; C), glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78; B), and CCAAT enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP; D), with Olig2, an oligodendrocyte-specific marker, at the injury epicenter at the indicated time points post-severe SCI. Arrows indicate the individual co-localized cells, one of which is identified in the XZ and YZ planes of the merged images (scale bar=50 μm). Identical data were observed in three independent experiments.

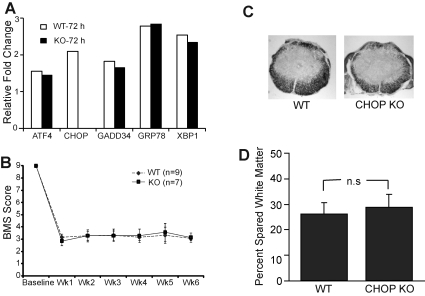

Deletion of CHOP does not result in functional recovery in mice with severe SCI

Considering the significant upregulation of CHOP mRNA in contused spinal cords specifically at the injury epicenter, we decided to utilize CHOP-null mice to evaluate its potential role in functional consequences of severe SCI. We first determined the UPR response in the CHOP-null mice 72 h post-severe injury. The relative gene expression values of ATF4, GADD34, GRP78, and XBP1 in wild-type and CHOP-null animals remained similar, suggesting identical UPR responses in both groups of animals to severe injury (Fig. 5A). A lack of CHOP expression in CHOP-null mice after severe injury as assessed by immunohistochemistry and Affymetrix gene expression (data not shown) confirmed that CHOP is truly knocked out. Analysis of BMS scores comparing wild-type and CHOP-null animals displayed scores of 3.17±0.25 and 2.86±0.38, respectively, at week 1, and 3.06±0.16 and 3.14±0.38, respectively, at week 6 (Fig. 5B). A BMS score of 3.0 correlates with a severe injury and is in accordance with an earlier study (Beare et al., 2009). CHOP-null mice did not show any enhanced functional recovery compared to wild-type animals at any of the time points tested. At 6 weeks post-injury, histological analysis showed no significant difference in the percentage of spared white matter in wild-type (27.46±4.6%) and CHOP-null (30±5.2%) mice (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that, unlike moderate contusive SCI, deletion of CHOP is not sufficient to enhance functional recovery after severe injury.

FIG. 5.

Deletion of CCAAT enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) does not result in functional recovery after severe spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analyses comparing contused wild-type (WT) and CHOP-null spinal cords for the indicated endoplasmic reticulum stress response (ERSR) markers show identical transcript levels in both groups. (B) Open field Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) locomotor analyses performed weekly following severe SCI did not reveal any functional recovery in CHOP-knockout (KO) mice (n=7; solid squares), compared to WT mice (n=9; solid diamonds) at any of the time points tested. (C) Representative histological cross-sections derived from the injury epicenter are stained with eriochrome cyanine (EC) to identify myelin in WT (left panel) and CHOP-KO (right panel) mice. (D) Quantitative analysis of EC-stained sections from the injury epicenters showed no difference in spared white matter in CHOP KO (30±5.2%), compared to WT mice (27.46±4.6%).

Discussion

Clinically, more than 40% of human SCI are complete (www.nscisc.uab.edu). Severe thoracic injury led to a rapid activation of all three arms of the ERSR pathway, specifically at the injury epicenter, implicating its role in the pathogenesis of SCI. In response to ER stress, PERK (the first signaling arm of ERSR) gets activated, which attenuates global protein synthesis by phosphorylating the α subunit of translation initiation factor 2 on Ser51 while promoting transcription of ATF4. The latter controls expression of CHOP, pro-apoptotic transcription factor, which in turn promotes expression of GADD34 (Mori, 2009; Rutkowski and Kaufman, 2004). ATF4 acts as a transcriptional activator for many target genes (heme oxygenase 1, stanniocalcin 2, osteocalcin, CHOP, and TRB3), which have been shown to play an important role in cell death and cell survival in the brain. Recent findings also establish ATF4 as a redox-regulated, pro-death transcriptional activator in the nervous system that propagates death responses to oxidative stress in vitro and to stroke in vivo. (Lange et al., 2008). This significant increase in the expression of ATF4, XBP1, GRP78, and CHOP transcript levels was apparent at 6 h post-SCI. Interestingly, GADD34 expression levels were highest as early as 1 h and remained higher until 12 h post-SCI. The temporal profile of the expression level of these ERSR components correlated with earlier mouse (Ohri et al., 2011) and rat (Penas et al., 2007) moderate SCI studies. However, the expression levels of the UPR markers in this study were higher and persisted longer than after moderate SCI (Ohri et al., 2011), likely due to differences in injury severity. Consistent with this interpretation, it is well documented that the resultant survival or cell death outcome of the ERSR depends on the injury severity and duration of injury (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). Another interesting observation is the persistent upregulation of CHOP mRNA (2.5 fold) until at least 72 h (the latest time point tested) after severe thoracic SCI. This contrasts with what is seen after moderate SCI, when CHOP mRNA returned to basal expression levels after 72 h (Ohri et al., 2011).

CHOP, also known as growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), is a member of the C/EBP family of bZIP transcription factors, and operates as a downstream component of the PERK-ATF4 arm of the ER-stress pathway. Overexpression of CHOP led to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Matsumoto, 1996; Oyadomari et al., 2001). In contrast, CHOP-null mice exhibited reduced apoptosis in response to ER stress (Oyadomari, 2002; Zinszner et al., 1998), showed smaller infarcts than wild-type animals subjected to bilateral carotid artery occlusion (Kohno et al., 1997), and displayed less tissue loss after stroke injury (Tajiri et al., 2004). In addition, we recently showed that CHOP-null mice displayed enhanced functional recovery compared to wild-type mice after moderate contusive SCI, an effect suggested to reflect oligodendrocyte protection (Ohri et al., 2011).

The fact that the current study showed no functional differences between the wild-type and CHOP-null animals after severe SCI could be explained by the complex transcriptional and translational interplay of various components of the ERSR pathway and the presence of other tissue-damaging pathways. For example, CHOP-null mice were not resistant to lethal doses of tunicamycin, an ER stress-causing agent (Zinszner et al., 1998), suggesting that other pro-apoptotic pathways are also active. ER stress-mediated cytotoxicity is regulated by at least three independent signaling cascades: transcriptional activation of CHOP, activation of the cJUN NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway through the ASK1 complex (Nishitoh et al., 2002; Urano et al., 2000), and activation of caspase 12 (Nakagawa et al., 2000). In addition, recent studies have implicated Bax and Bak as executioners for ER stress-mediated apoptosis (Wei et al., 2001; Zong et al., 2001). ER stress can also activate the Bcl-2 (Annis et al., 2004; Thomenius and Distelhorst, 2003) and caspase families of proteins (Boyce and Yuan, 2006). ER stress itself can upregulate or activate several BH3-only pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, including Bim (Morishima et al., 2004), BIK (Germain et al., 2005; Mathai et al., 2005), and PUMA (Luo et al., 2005). Therefore, efferent signaling from the stressed ER can engage diverse cytotoxic pathways directly, resulting in massive cell death. Compounding this, each of the distinct insults (inflammation, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and trauma) which underlie the complex pathophysiology of SCI (Baptiste et al., 2009; Hall and Springer, 2005) has the potential to induce the ERSR that may possibly result in severe protein misfolding and lead to autophagy. Consistent with this suggestion, severe protein misfolding results in insoluble protein aggregates in the cells that cannot be removed by the ubiquitin/proteaome system and are eliminated by autophagy (Bernales et al., 2006). To identify yet other potential pathways, microarray analyses comparing wild-type and CHOP-null mice demonstrated significant threefold enrichment of the p53 pathway, chemokine signaling pathway, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, ErbB signaling pathway, Fc epsilon Ri signaling pathway, and B-cell receptor signaling pathway (data not shown), suggesting additional cell-death and inflammatory pathways to be upregulated/enriched in the CHOP-null mice after severe injury.

The clinical significance of the current data is twofold. With increasing injury severity, both the magnitude and duration of the ERSR were increased, and that increase likely activated multiple cytotoxic mechanisms besides CHOP. Identifying additional key effectors downstream of the ER-mediated cytotoxicity pathways and ER-independent pathways may provide a basis for new therapeutic approaches for treating SCI. However, a parallel cautionary interpretation would be that with very severe SCI (e.g., clinically complete), pharmacological interventions to reduce secondary cell death may be ineffective both due to the extent of initial tissue destruction, as well as excessive activation of cell death pathways.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this manuscript was supported by RR15576, The Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust, Norton Healthcare, the Commonwealth of Kentucky Challenge for Excellence, and NS073584 (to M.H. and S.R.W.), NS047341 (to M.H.), and NS054708 (to S.R.W.). We thank Christine Nunn for help with surgical procedures, Kimberly Fentress for assistance with post-operative animal care, and Darlene A. Burke for help with statistical analyses.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Annis M.G. Yethon J.A. Leber B. Andrews D.W. There is more to life and death than mitochondria: Bcl-2 proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1644:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste D.C. Tighe A. Fehlings M.G. Spinal cord injury and neural repair: focus on neuroregenerative approaches for spinal cord injury. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;18:663–673. doi: 10.1517/13543780902897623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso D.M. Fisher L.C. Anderson A.J. Jakeman L.B. McTigue D.M. Popovich P.G. Basso mouse scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma. 2006;25:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare J.E. Morehouse J.R. DeVries W.H. Enzmann G.U. Burke D.A. Magnuson D.S. Whittemore S.R. Gait analysis in normal and spinal contused mice using the TreadScan system. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:2045–2056. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S. McDonald K.L. Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce M. Yuan J. Cellular response to endoplasmic reticulum stress: a matter of life and death. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:363–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri K.F. Kroemer G. Organelle-specific initiation of cell death pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E255–E263. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-e255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M. Mathai J.P. McBride H.M. Shore G.C. Endoplasmic reticulum BIK initiates DRP1-regulated remodeling of mitochondrial cristae during apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:1546–1556. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Springer J.E. Neuroprotection and acute spinal cord injury: a reappraisal. NeuroRx. 2005;1:80–100. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluk G.W. Rowland J. Kown B.K. Fehlings M.G. Protection and repair of the injured spinal cord: a review of completed, ongoing and planned clinical trials for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008;25:E14. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno K. Higuchi T. Ohta S. Kumon Y. Sakaki S. Neuroprotective nitric oxide synthase inhibitor reduces intracellular calcium accumulation following transient global ischemia in the gerbil. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;224:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange P.S. Chavez J.C. Pinto J.T. Coppola G. Sun C.W. Townes T.M. Geschwind D.H. Ratan R.R. ATF4 is an oxidative stress-inducible, prodeath transcription factor in neurons in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:227–1242. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. Kemper A. Dupree J.L. Harding H.P. Ron D. Popko B. Interferon-γ inhibits central nervous system remyelination through a process modulated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Brain. 2006;129:1306–1318. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X. He Q. Huang Y. Sheikh M.S. Transcriptional upregulation of PUMA modulates endoplasmic reticulum calcium pool depletion-induced apoptosis via Bax activation. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1310–1318. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson D.S. Lovett R. Coffee C. Gray R. Han Y. Zhang Y.P. Burke D.A. Functional consequences of lumbar spinal cord contusion injuries in the adult rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:529–543. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathai J.P. Germain M. Marcellus R.C. Shore G.C. Induction and endoplasmic reticulum location of BIK/NBK in response to apoptotic signaling by E1A and p53. Oncogene. 2002;21:2534–2544. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M. Minami M. Takeda K.M. Sakao Y. Akira S. Ectopic expression of CHOP (GADD153) induces apoptosis in M1 myeloblastic leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhavet O. Marindale J.L. Camandola S. Chan S.L. Gary D.S. Cheng A. Holbrook N.J. Mattson M.P. Involvement of Gadd153 in the pathogenic action of presenilin-1 mutations. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:673–681. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K. Signalling pathways in the unfolded protein response: development from yeast to mammals. J. Biochem. 2009;146:743–750. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima N. Nakanishi K. Tsuchiya K. Shibata T. Seiwa E. Translocation of Bim to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) mediates ER stress signaling for activation of caspase-12 during ER stress-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50375–50381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T. Zhu H. Morishima N. Li E. Xu J. Yankner B.A. Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitoh H. Matsuzawa A. Tobiume K. Saegusa K. Takeda K. Inoue K. Hori S. Kakizuka A. Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohri S.S. Maddie M.A. Zhao Y. Qiu M.S. Hetman M. Whittemore S.R. Attenuating the ER stress response improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Glia. 2011;59:1489–1502. doi: 10.1002/glia.21191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S. Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S. Araki E. Mori M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells. Apoptosis. 2002;7:335–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1016175429877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S. Takeda K. Takiguchi M. Gotoh T. Matsumoto M. Wada I. Akira S. Araki E. Mori M. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas C. Guzmán M.S. Verdú E. Forés J. Navarro X. Casas C. Spinal cord injury induces endoplasmic reticulum stress with different cell-type dependent response. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:1242–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D. Habener J.F. CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:439–453. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski D.T. Kaufman R.J. A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowshi D.T. Kaufman R.J. That which does not kill me makes me stronger: Adapting to chronic ER stress. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri S. Oyadomari S. Yano S. Morioka M. Gotoh T. Hamada J.-I. Ushio Y. Mori M. Ischemia-induced neuronal cell death is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway involving CHOP. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:403–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomenius M.J. Distelhorst C.W. Bcl-2 on the endoplasmic reticulum: protecting the mitochondria from a distance. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:4493–4499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano F. Wang X. Bertolotti A. Zhang Y. Chung P. Harding H.P. Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M.C. Zong W.X. Cheng E.H. Lindsten T. Panoutsakopoulou V. Ross A.J. Roth K.A. MacGregor G.R. Thompson C.B. Korsmeyer S.J. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H. Matsui T. Yamamota A. Okada T. Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.P. Burke D.A. Shields L.B.E. Chekmenev S.Y. Dincman T. Zhang Y. Zheng Y. Smith R.R. Benton R.L. DeVries W.H. Hu X. Magnuson D.S.K. Whittemore S.R. Shields C.B. Spinal cord contusion based on precise vertebral stabilization and tissue displacement measured by combined assessment to discriminate small functional differences. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:1227–1240. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinsner H. Kuroda M. Wang X. Batchvarova N. Lightfoot R.T. Remotti H. Stevene J.L. Ron D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong W.X. Lindsten T. Ross A.J. MacGregor G.R. Thompson C.B. BH3-only proteins that bind pro-survival Bcl-2 family members fail to induce apoptosis in the absence of Bax and Bak. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1481–1486. doi: 10.1101/gad.897601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]