Abstract

The structures of functional peptides corresponding to the predicted channel-lining M2 segments of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) and of a glutamate receptor of the NMDA subtype (NMDAR) were determined using solution NMR experiments on micelle samples, and solid-state NMR experiments on bilayer samples. Both M2 segments form straight transmembrane α-helices with no kinks. The AChR M2 peptide inserts in the lipid bilayer at an angle of 12° relative to the bilayer normal, with a rotation about the helix long axis such that the polar residues face the N-terminal side of the membrane, which is assigned to be intracellular. A model built from these solid-state NMR data, and assuming a symmetric pentameric arrangement of M2 helices, results in a funnel-like architecture for the channel, with the wide opening on the N-terminal intracellular side.

Neurotransmitter-gated ion channels, a superfamily of oligomeric proteins in the postsynaptic membrane of neurons, are responsible for neuronal communication. They sense the presence of neurotransmitter molecules released into the synaptic cleft by binding them as ligands, and undergo a conformational change that allows ions to pass through a pore formed by the protein1. The extensive sequence similarity among members of the superfamily of neurotransmitter-gated channels suggests that these proteins may also have similar three-dimensional structures. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) and ionotropic glutamate receptors, the major excitatory neurotransmitters in the brain, are thought to be pentameric assemblies1–3. The canonical folding topology of these receptors considers four potential transmembrane segments, M1–M4, in each of the five subunits. The M2 segments are of particular interest. Their sequences are highly conserved, they are predicted to be amphipathic α-helices, and a plethora of mutagenesis and affinity-labeling studies identify them as the major polypeptide component of the pores responsible for the ion-channel activities of acetylcholine and glutamate receptors1–3. The structure of the Torpedo marmorata AChR, determined by cryoelectron microscopy with image reconstruction at a resolution of 9 Å, has provided a model in which the channel pore is formed by a bundle of five M2 α-helices, each contributed by one subunit of the AChR pentamer4. Conformational energy calculations, refined using molecular dynamics, are consistent with a pentameric M2 helical bundle as the structural motif underlying the ion-conductive pore of the AChR5. This model is also compatible with mutagenesis and substituted-cysteine accessibility data from glutamate receptors6. An alternative view of the glutamate receptor, based on the location of glycosylation and phosphorylation sites in this family, assigns the N- and C-termini to the extracellular and intracellular faces of the protein subunits, and proposes three transmembrane segments, M1, M3 and M4, with the M2 helix as a ‘re-entrant loop’ on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane7.

Here, we describe the three-dimensional structures of two functional peptides, corresponding to the M2 segments from the δ-subunit of the AChR, and the NR1 subunit of the NMDA-subtype glutamate receptors (NMDAR), determined by solution and solid-state NMR spectroscopy in membrane environments. The relatively large quantities of isotopically labeled M2 peptides required for NMR spectroscopy were prepared by expression of recombinant peptides in Escherichia coli, for selective or uniform isotopic labeling, or by solid-phase synthesis, for specific residue labeling of the samples. An important feature of our approach is the direct correlation of the structures obtained by NMR spectroscopy in lipid micelles and bilayers, with the functional properties of the channels recorded after reconstitution of the same peptides into lipid bilayers.

M2 peptides form ion channels in lipid bilayers

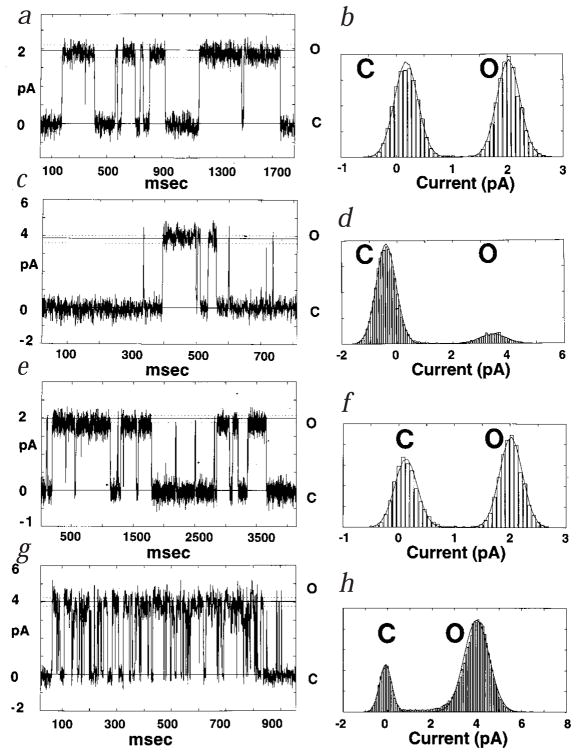

The incorporation of M2 peptides in lipid bilayers reconstitutes functional, cation-selective channels for both AChR and NMDAR. Single-channel currents were recorded from AChR M2 in lipid bilayers, under voltage clamp conditions, for symmetric NaCl (Fig. 1a), and for symmetric KCl (Fig. 1c). The channels have heterogeneous conductances and lifetimes, as expected for monomeric peptides that self-assemble into conductive oligomers of discrete yet variable size, and display a linear current–voltage relationship over the range from −100 mV to 100 mV8. The channels that occur most frequently exhibit a single-channel conductance of 37 ± 2 pS in NaCl and 38 ± 2 pS in KCl. The corresponding single-channel current histograms show the fitted Gaussian distributions for the channel-closed and channel-open states, in either NaCl (Fig. 1b) or KCl (Fig. 1d). The probability of the channel being open is 0.11 in K+ at 100 mV, whereas in Na+ at 50 mV, the two states appear to be equally populated.

Fig. 1.

a–h, Single-channel recordings from recombinant M2 peptides in lipid bilayers. The currents were recorded at constant voltage in symmetric 500 mM NaCl or KCl supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES pH 7.4. The currents of closed (C) and open (O) states are indicated by the solid lines. Dotted lines define the range set to discriminate the transitions between states, based on signal-to-noise measurements. The AChR M2 traces show bursts of channel activity with single-channel conductances of 37 ± 2 pS in 500 mM NaCl at 50 mV (a), and 38 ± 2 pS in 500 mM KCl at 100 mV (c). For NMDAR M2, single-channel conductances of 20 ± 2 pS NaCl (e), and 40 ± 3 pS in 500 mM KCl (g) were measured. Both NMDAR traces were recorded at 100 mV. In the corresponding histograms for AChR M2 (b, d) and for NMDAR M2 (f, h), the Gaussian fits of the data in NaCl (b, f) or KCl (d, h) indicate the respective probabilities of the open- (O) versus closed- (C) channel states.

The single-channel traces from recombinant NMDAR M2 reconstituted in bilayers, obtained in symmetric NaCl (Fig. 1e) or symmetric KCl (Fig. 1g) show that, as seen for AChR, the NMDAR M2 peptide forms channels of heterogeneous conductances with ohmic behavior. The most frequent channels recorded in NaCl display conductances of 20 ± 2 pS. In contrast, the most frequent channels observed in KCl have conductances of 40 ± 3 pS, with sporadic occurrences of 190 pS. These channels consistently appear in bursts of activity with a high probability of residing in the open state. Indeed, the current histograms indicate that the probability of the channel being open is 0.80 in K+, compared to 0.57 in Na+ (Fig. 1f and h).

Significantly, the channel properties of peptides prepared by solid-phase synthesis and by expression in bacteria are nearly identical. Furthermore, peptides with the same amino acid composition as the M2 but with scrambled sequences do not form channels, nor do peptides patterned after the sequences of the predicted M1, M3 or M4 helices. Taken together, these results indicate that both the recombinant and synthetic AChR and NMDAR M2 peptides used in the NMR experiments are functional, and form sequence-specific, discrete ion channels in lipid bilayers. To the extent that these peptides mimic the predicted channel-lining sequence, their permeation properties compare favorably with those of the intact homomeric AChR and NMDAR.

Solution NMR structures of M2 peptides in lipid micelles

Lipid bilayers and micelles provide membrane environments for quite different types of NMR studies of membrane proteins, because of the vast differences in the overall reorientation rates exhibited by polypeptides in these two systems9. The reorientation rate of a 25-residue polypeptide (10−8 s) in micelles averages the nuclear-spin interaction tensors to their isotropic values, with resonances narrow enough for most multidimensional solution NMR experiments. In contrast, the same polypeptides in bilayers are immobile (10−3 s) on the relevant NMR time scales, and require the use of solid-state NMR experiments.

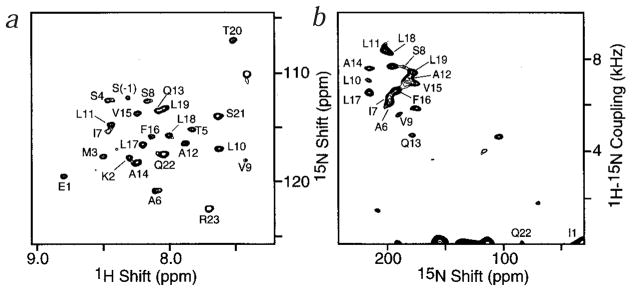

The two-dimensional solution 1H-15N HMQC (heteronuclear multiple-quantum correlation) NMR spectrum of uniformly 15N-labeled AChR M2 peptide in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles, at 20 °C, is well resolved, with each amide resonance characterized by isotropic 1H and 15N chemical-shift frequencies (Fig. 2a). Not surprisingly, the effect of the micelles on the reorientation rate is seen in linewidths that are somewhat broader than expected for a peptide of this size in aqueous solution, at this temperature. The two-dimensional solid-state polarization inversion spin exchange at the magic angle (PISEMA) spectrum of the same peptide in oriented bilayers (Fig. 2b) has similar resolution, with each amide resonance characterized by 15N chemical shift and 1H-15N dipolar coupling frequencies.

Fig. 2.

Solution and solid-state 2D NMR spectra of AchR M2 peptides. a, Solution 1H chemical-shift/15N chemical-shift correlation HMQC NMR spectrum of AChR M2 in DPC micelles, at 20 °C. Four transients were acquired for each of 256 t1 increments. b, Solid-state 1H-15N dipolar/15N chemical-shift correlation PISEMA NMR spectrum of AChR M2 in oriented DMPC bilayers, at 22 °C. A total of 256 transients were acquired for each of 64 t1 values incremented by 40.8 μs.

As expected for a helical peptide, the overlap in the amide NH and CαH regions of the solution NMR spectra of the AChR peptide made it difficult to assign the resonances from 15N-edited TOCSY and NOESY experiments alone. In order to obtain complete backbone resonance assignments, and to measure the 13Cα chemical shifts, three-dimensional HNCA10 and HNCO-CA11 experiments were performed on uniformly 13C- and 15N-labeled AChR M2 samples. The 1H-15N correlation resonances of the NMDAR M2 peptide in micelles are somewhat better resolved than those of the AChR M2 peptide; therefore sequential resonance assignment did not require the use of 13C-labeled samples.

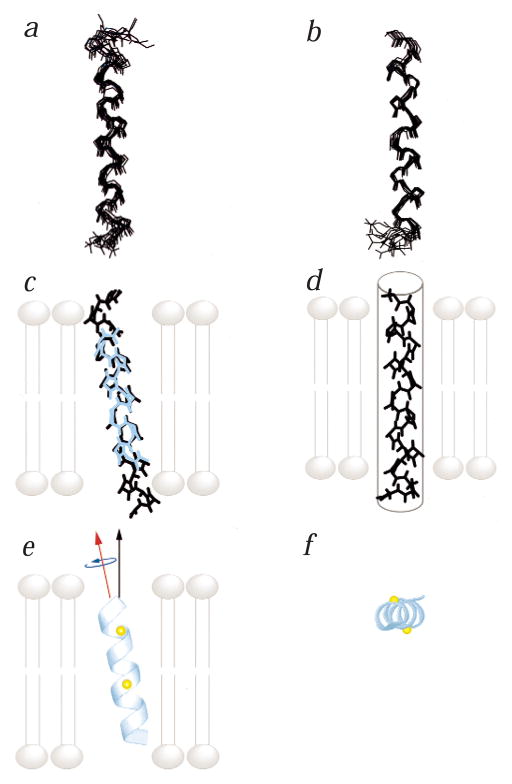

The primary constraint used for structure determination by solution NMR spectroscopy is the homonuclear 1H-1H NOE12. We provide here the structures of the AChR (Fig. 4a) and NMDAR M2 (Fig. 4b) peptides that satisfy the NMR data, with no NOE violations >0.5 Å and no dihedral-angle violations >5°, and that maintain acceptable peptide geometry. The AChR M2 structures overlay best from residues Lys 2 to Gln 22, while the NMDAR M2 structures overlay best from Asp 1 to Ile 21. In these well-defined regions, the average r.m.s.d. of the heavy atoms of the backbone from the calculated average of the accepted structures is 0.77 ± 0.2 Å for AChR, and 0.63 ± 0.1 Å for NMDAR. Both M2 peptides adopt α-helical structures in DPC micelles, that are only slightly curved and show no evidence of kinks.

Fig. 4.

Superposition of the backbone heavy atoms for the 10 lowest energy structures of a, AChR M2 and b, NMDAR M2, determined by solution NMR in DPC micelles. The four residues preceding the native sequence of NMDA M2 were not constrained in the structure calculations and are not shown. c, Superposition of the average structure of the AChR M2 calculated from the solution NMR distance constraints (black), and the average structure determined from the solid-state NMR orientational constraints (cyan). Both structures are shown in the bilayer membrane, in the exact overall orientation determined from solid-state NMR. d, Average structure of NMDAR M2, calculated from solution NMR experiments. The peptide is shown in the transmembrane orientation (gray tube) determined from the one-dimensional solid-state NMR spectrum. The exact tilt in the membrane is not determined because of the limited 15N chemical-shift data for this peptide. e,f, Side (e) and top (f) views of the average structure of AChR M2 in lipid bilayers, determined from solid-state NMR orientational constraints. The peptide is shown in its exact overall orientation within the lipid bilayer. The N-terminus is on top in (e), and in front in (f). The Cα atoms of Ser 8 and Gln 13 are highlighted in yellow. The helix long axis (red arrow) is tilted 12° from the membrane normal (black arrow). The helix rotation about its long axis (blue arrow) is such that the polar residues Ser 8 and Gln 13 face the N-terminal side of the lipid bilayer. In (c), (d) and (e) the lipid bilayer membrane is shown in gray.

Solid-state NMR studies of M2 peptides in lipid bilayers

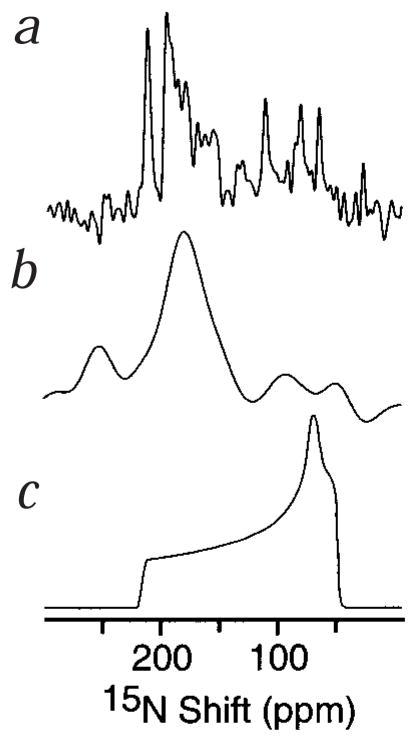

The orientation of the peptides within the bilayer membrane is reflected in the one-dimensional solid-state 15N chemical-shift NMR spectra of 15N-labeled M2 peptides in oriented phospholipid bilayers (Fig. 3). In these spectra, each 15N resonance arises from a single nitrogen atom in the protein, and has a frequency that reflects the orientation of the corresponding NH bond in the lipid bilayer membrane13. The powder pattern spectrum, simulated for an unoriented, immobile 15N amide site, spans the full 60–220 p.p.m. range of the chemical-shift interaction (Fig. 3c). The spectrum obtained from an oriented sample of uniformly 15N-labeled AChR M2 peptide (Fig. 3a) is striking for its high resolution as well as the amount of structural information it contains. Because the majority of 15N resonances are observed near 200 p.p.m., at the downfield, σ33, end of the powder pattern, it is possible to conclude that this helical peptide has a transmembrane orientation. In an α-helix the amide NH bonds align with the long helix axis, so that finding the NH bonds oriented parallel to the bilayer normal implies that the helix is transmembrane. Although the spectrum from oriented uniformly 15N-labeled NMDAR M2 lacks the resolution observed in its AChR counterpart, it displays similar features (Fig. 3b). The peak resonance intensity also occurs near σ33, in the 15N spectrum. These results firmly establish that the NMDAR M2 α-helical peptide is transmembrane, in accord with mutational and cysteine-accessibility measurements6, and argue against the ‘re-entrant loop’ model for the M2 segment of glutamate receptors7. Specifically, the N-site (corresponding to Asn 18), a key structural determinant of channel selectivity and blockade, is accessible to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. A revised topology, based on the M2 transmembrane helical structure, would propose an ascending M2 α-helix N-terminal (DALTLSSAMWFSWGVLLN), and a descending extended structure C-terminal to the N-site, in agreement with mutation and accessibility findings6,7. The average solution NMR structure of NMDAR M2, placed in the transmembrane orientation, determined by solid-state NMR in bilayers, is shown (Fig. 4d). No helix tilt is shown because the limited 15N chemical-shift data, for this peptide in bilayers, preclude the determination of its exact orientation within the membrane. However, as for AChR, modest tilt angles are compatible with the 1D solid-state 15N chemical-shift NMR data (Fig. 3). These results show a very strong similarity between the structural and functional properties of the AChR and NMDAR M2 peptides. It is likely that they reflect a similar organization of the receptor proteins from which the peptide sequences were determined.

Fig. 3.

One-dimensional solid-state 15N chemical-shift NMR spectra of M2 peptides in oriented lipid bilayers. a, Uniformly 15N-labeled AChR M2 in DMPC bilayers. b, Uniformly 15N-labeled NMDAR M2 in POPC/DOTAP bilayers. c, Simulated chemical-shift powder pattern of an immobile 15N amide site.

Solid-state NMR structure of AChR M2 in lipid bilayers

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy can be used independently to determine the three-dimensional structures of membrane proteins in bilayers13,14. The orientationally dependent 15N chemical shift and 1H-15N dipolar coupling frequencies provide orientational constraints for structure determination of 15N-labeled peptides in lipid bilayer membranes, and can be measured directly from the two-dimensional PISEMA spectrum of the AChR M2 peptide (Fig. 2b). In this spectrum, the presence of a single resonance for each individual residue implies that the AChR M2 peptides adopt a unique conformation in the lipid bilayer membrane. Sequential resonance assignments are essential in both solution and solid-state NMR experiments. Most of the resonances in Figure 2b were assigned to specific residues through comparisons with spectra from selectively 15N-labeled recombinant peptides, and specifically 15N-labeled synthetic peptides. Some resonances were assigned with 15N dilute spin-exchange experiments15. In a helix, the backbone 15N nuclei are ~2.7 Å apart, close enough for spin exchange to occur. The crosspeaks between neighboring 15N nuclei, observed in a three-dimensional 15N chemical-shift/15N chemical-shift/1H - 15N dipolar coupling spin-exchange spectrum, were used to trace the backbone connectivity between residues 6 and 10.

The backbone structure of AChR M2, determined from solid-state NMR 15N chemical-shift and 1H-15N dipolar coupling constraints, is shown (Fig. 4c, e and f). Superposition of the solution and solid-state NMR structures (Fig. 4c) shows that they are very similar, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.6 Å for the backbone atoms. Although both methods yield three-dimensional structures with atomic resolution, solid-state NMR on oriented lipid bilayer samples is unique in determining the complete topology, including three-dimensional structure and global orientation, of the peptide in the membrane, at high resolution. This is a crucial element of membrane protein structure, and in the case of AChR M2 sheds light on the details of supramolecular channel architecture. Using the solid-state NMR orientational constraints, we determined that the AChR M2 peptide is a transmembrane, amphipathic α-helix with its long helix axis tilted 12° from the lipid bilayer normal (78° from the lipid bilayer plane) (Fig. 4e, f), in agreement with the structure inferred from the 9 Å electron diffraction map4. The peptide is rotated around its helix long axis such that the polar residues face the N-terminal side of the membrane, which is assigned to be intracellular1,2,5. In solid-state NMR of oriented lipid bilayer samples, three-dimensional structural coordinates are determined directly from the NMR data relative to an external reference, namely the lipid bilayer normal, which is set parallel to the magnetic field by the method of sample preparation. As a result, the three-dimensional structure of the M2 peptide is fixed within the lipid bilayer, and inherently contains the helix tilt and helix rotation information. This implies that the solid-state NMR structure must be viewed as a supramolecular assembly, together with the bilayer membrane.

Molecular model of the AChR M2 channel structure

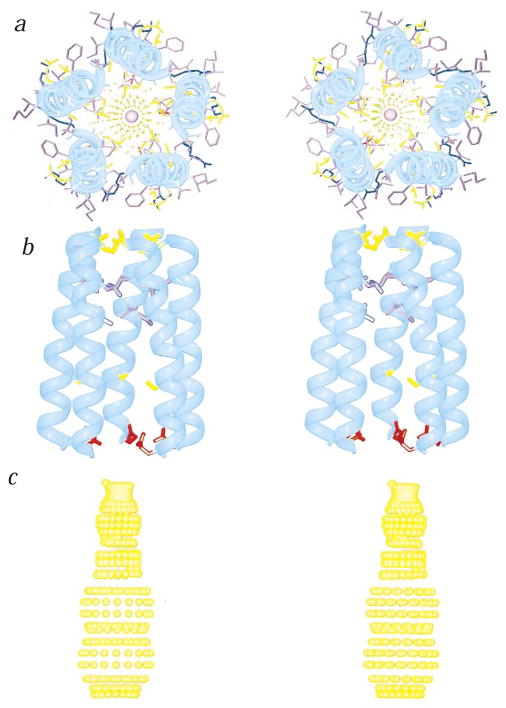

We provide a molecular model of the AChR channel pore, constructed from the solid-state NMR three-dimensional structure of the AChR M2 helix in the membrane, and assuming a symmetric pentameric organization of the channel (Fig. 5a–c)2. The crystal structure of a bacterial potassium channel shows that the tetrameric pore has a funnel-like architecture, with each subunit contributing two transmembrane α-helical segments, tilted by 25° with respect to the bilayer normal16. Overall, these structural features are similar to those shown in Figure 5. The optimized parallel, five-helix bundle has a right-handed, interhelical twist with an orientation angle of 12° (Fig. 5a). A central narrow pore has a diameter ranging from ~3.0 Å at its narrowest, to 8.6 Å at its widest. Nonpolar residues are predominantly on the exterior of the bundle, while polar residues line the pore. The residues exposed to the pore lumen are Glu 1, Ser 4, Ser 8, Val 15, Leu 18 and Gln 22. This arrangement is in agreement with the evidence collected from mutagenesis, affinity labeling and cysteine-accessibility measurements1,2,5,17,18. A side view (Fig. 5b) shows a funnel-shaped bundle, 33 Å in length, with the wide mouth at the N-terminus, which is assigned to be intracellular1,2,5. A dotted contour depicting the profile of the ion-conduction pore, calculated from the structure, shows a wide infundibulum leading to two narrow constrictions generated by rings of Val 15 and Gln 22, with hole radii of 2.9 Å and 1.5 Å, respectively (Fig. 5c). The channel-lining hydroxyl residues are in agreement with the expectations of a water-filled pore, and the constrictions are compatible with the permeation of both Na+ and K+ ions (ionic radii of 0.95 Å and 1.33 Å, respectively). The wide cavity delimited between Ser 8 and Val 15 is consistent with the binding pocket for open-channel blockers2,5,19. The earlier finding that the M2 segments of the glycine receptor (GlyR) family, a major inhibitory neurotransmitter, are transmembrane α-helices as determined by NMR spectroscopy20, supports the structural kinship of AChR, NMDAR and GlyR. Therefore, we propose that a pentameric M2 helical bundle represents the structural blueprint for the inner bundle that lines the pore of neurotransmitter-gated channels.

Fig. 5.

a–c, Top (a) and side (b,c) stereo views of a model of the AChR M2 funnel-like pentameric bundle. The channel architecture was calculated using the solid-state NMR three-dimensional coordinates of the M2 helix in the lipid bilayer, and by imposing a symmetric pentameric organization. The top view has the C-terminal synaptic side in front. The wide mouth of the funnel is on the N-terminal, intracellular side of the pore. A sodium ion is confined within the pore. The side views have the C-terminus on top. In (b), only the side chains of the pore-lining residues, Glu 1, Ser 8, Val 15, Leu 18 and Gln 22, are shown. In (c), the dotted contour depicts the pore profile calculated using the program HOLE36; it represents the minimum radial distance between the center of the pore lumen and the van der Waals protein contact. The hole radii for the residues facing the pore lumen are 3.3 Å (Glu 1); 4.3 Å (Ser 8); 2.9 Å (Val 15); 2.1 Å (Leu 18); 1.5 Å (Gln 22). Ribbon diagrams were drawn using MOLSCRIPT38. The α– carbon backbone is shown in cyan; acidic residues are in red, basic residues in blue, polar residues in yellow, and lipophilic residues in purple.

Methods

M2 peptides

Recombinant peptides were derived from fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Amino acid sequences corresponding to the M2 segments were separately cloned into the glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), or maltose binding (MBP) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) fusion protein expression systems. For uniformly labeled samples, E. coli cells were grown in media containing 15N-enriched ammonium sulfate with or without uniformly 13C-enriched glucose. For selectively labeled samples, the growth media contained all amino acids with only one type 15N labeled. The fusion proteins were isolated by affinity or ion-exchange chromatography, and cleaved enzymatically. The M2 peptides were isolated by gel filtration or ion-exchange chromatography, and purified by HPLC. After cleavage from the carrier protein, the recombinant AChR M2 peptide has the sequence XSEKMSTAISVL-LAQAVFLLLTSQR, where X is Gly in peptides derived from GST-AChR, or Ile in peptides derived from MBP-AChR M2 fusion proteins. The sequence of the cleaved recombinant NMDAR M2 peptide is XDALTLSSAMWFSWGVLLNSGIGYE, where X is GSNG and Y is E in the GST-derived peptide, and X is GIEEEEE and Y is EGAPR in the MBP-derived peptide. In both cases, the underlined residues are introduced by the expression system. All isotopically labeled materials were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Cambridge, MA). Synthetic peptides were prepared as described21.

Electrophysiology

Lipid bilayers were assembled by apposition of two monolayers composed of diphytanoylphosphatidylethanolamine (PE)/diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (PC) in a 4:1 weight ratio (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), as described8. Purified peptides were dissolved in trifluoroethanol (TFE) at 0.01 mg ml−1 and added to the aqueous subphase after bilayer formation. Acquisition and analysis of single-channel currents at 24 ± 2 °C were as described8. Records were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 0.5 ms point−1. The channel recordings illustrated are representative of the most frequently observed conductances under the specified experimental conditions. Conductances were calculated from Gaussian fits to current histograms, and lifetimes from exponential fits to probability density functions using data from segments of continuous recordings lasting 30 s or longer and with n > 300 openings (mean ± s.e.m.).

Solution NMR spectroscopy

Experiments were performed at 30 °C on Bruker DMX spectrometers. For the 1H-15N HMQC (ref. 22) NMR spectra, 2,048 complex points were acquired for each of 128 or 256 points in the indirect dimension. WATERGATE water suppression was used in most cases23. Typical spectral widths for the 1H and 15N dimensions were 12 p.p.m. and 30 p.p.m., respectively. The NMR data were processed using the program XWIN-NMR (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA). The samples were prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg of peptide in 90% acetonitrile in water, containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid for AChR, or 0.1% ammonium hydroxide for NMDAR. After adding 32 mg of uniformly deuterated DPC, the bulk acetonitrile was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the peptide lipid mixture was lyophilized. The resulting dry powder was dissolved in 200 μl of water plus 20 μl of D2O, and the pH adjusted to 5.5.

NOE crosspeaks in the 13C- or 15N-edited NOESY experiments were classified as strong, medium or weak, corresponding to distance restraints of 1.9–2.5 Å, 1.9–3.5 Å, and 1.9–5.0 Å, respectively24. Distance restraints involving nonstereospecifically assigned hydrogens were adjusted with the appropriate pseudoatom correction, and 1.5 Å were added to the upper limits of distances involving methyl hydrogens. Restraints for the dihedral angles φ were derived from analysis of the three-dimensional HNHA spectrum25. Residues with 3JHN, Hα coupling constants <5.5 Hz were given a target value for φ of −60° ± 25°. In order to detect slowly exchanging amide protons, a series of two-dimensional 1H-15N HMQC spectra were acquired from a freshly prepared sample in D2O. Those amide resonances detectable after 2 h were classified as having protons in slow exchange, that participate in hydrogen bonding. Hydrogen bond constraints were added to the structure by fixing the distance between the amide nitrogen of residue i and the carbonyl oxygen of residue i − 4 to be 2.8 ± 0.5 Å, and by fixing the distance between the amide proton of residue i and the carbonyl oxygen of residue i − 4 to be 1.8 ± 0.5 Å. For AChR M2, 138 NOEs, 16 dihedral and 12 hydrogen bond restraints were used in the structure calculation. For NMDAR M2, 144 NOEs, 17 dihedral and 12 hydrogen bond restraints were used. Three-dimensional structures were calculated with the program X-PLOR 3.126. A protocol of distance geometry, simulated annealing and energy minimization was used. The NOE and torsion angle potentials were calculated with force constants of 50 kcal mol−1 Å−2 and 200 kcal mol−1 rad−2, respectively. A linear template with random backbone angles was used as the starting structure.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Experiments were performed on a home-built spectrometer with a wide-bore Magnex 550/89 magnet, and on a Chemagnetics-Otsuka Electronics (Fort Collins, CO) spectrometer with a wide-bore Oxford 400/89 magnet. The home-built single-coil probes were double tuned to the resonance frequencies of 1H at 549.9 (400.4) MHz, and 15N at 55.7 (40.6) MHz. In both probes the square, four-turn coils had inner dimensions of 11 × 11 × 2 mm. One-dimensional 15N chemical-shift spectra were obtained with single-contact, 1 ms, CPMOIST (cross-polarization with mismatch-optimized IS transfer) under continuous 1H irradiation to decouple the 1H-15N dipolar interaction27,28. Two-dimensional 15N chemical shift/1H-15N dipolar coupling were obtained with the PISEMA pulse sequence29. For some of the specifically 15N-labeled AChR M2 samples, two-dimensional 15N chemical-shift/1H chemical-shift heteronuclear correlation spectra were obtained by fixing the SEMA (spin exchange at the magic angle) period, which is incremented in the three-dimensional correlation pulse sequence30. Conditions for the one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR experiments were as described31. The three-dimensional 15N chemical-shift/15N chemical-shift/1H-15N dipolar coupling experiment, with 15N resonances correlated by homonuclear spin exchange and to 1H-15N dipolar coupling, is based on the PISEMA pulse sequence and has been described15. A mixing time of 3 s was used to allow 15N magnetization spin exchange. The NMR data were processed using the program FELIX (Biosym Technology, San Diego, CA). The 15N chemical shift was referenced to liquid ammonia at 0 p.p.m.

For the AChR M2 samples, 40 mg of 1,2-dimirystoyl-sn-glycero phosphocholine (DMPC) powder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) were dissolved in TFE and added to 2 mg of dry peptide. The solution was bath-sonicated for 5 min and allowed to stand overnight at −20 °C. In order to prepare oriented samples, the TFE solution was evenly distributed over the surface of 25 glass plates measuring 11 × 11 mm. After evaporation of the bulk organic solvent, the plates were placed under high vacuum for 3 h in order to remove residual TFE; 2 μl of sterile filtered water were then added to each plate, and the plates were stacked and placed in a chamber containing a saturated solution of ammonium phosphate. Oriented bilayers formed after equilibrating the sample in this chamber at 30 °C for 15 h. Before insertion into the coil of the NMR probe, the stacked glass plate sample was wrapped in a thin layer of parafilm, and then placed in a thin film of polyethylene, which was heat-sealed at both ends to maintain sample hydration during the experiments.

For the NMDAR M2 bilayer sample, 0.5 mg of peptide were dissolved in 220 μl of 450 mM sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS). In a separate test tube, 80 mg of combined 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero phosphocholine (POPC) and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP) lipids, in a molar ratio of 4:1 (POPC:DOTAP), were suspended in 5 ml of water and sonicated to transparency, using a Branson sonifier equipped with a micro tip. The peptide–SDS solution was added to the vesicle suspension, and the mixture was quickly frozen. After thawing at room temperature, the sample was diluted by the addition of 40 ml of water, and subsequently dialyzed against water for 3 days. The reconstituted-vesicle preparation was concentrated to 2 ml, and then distributed over the surface of 25 glass slides measuring 11 × 11 mm. After evaporation of the bulk water at 42 °C, the plates were stacked and rehydrated as described for AChR M2.

The procedure for structure determination of proteins in oriented bilayers, from solid-state NMR-derived orientational constraints, has been described13, 32. A standard peptide geometry served as the building block for the structure assembly process. The peptide unit was assumed to be planar with the dihedral angle ω= 180°. The 15N chemical shift and 1H-15N coupling frequencies measured from the PISEMA spectrum of uniformly 15N-labeled AChR M2 (Fig. 2b), the 1H chemical-shift frequencies measured from two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation spectra of specifically 15N-labeled AChR M2, and the values of the amide 15N and 1H chemical-shift tensors33 were the input for the FORTRAN program RESTRICT, that calculates the allowed orientations of a peptide plane relative to the magnetic field34. Neighboring peptide planes of fixed orientation were connected through their common Cα atom, using the FORTRAN program FISI, which calculates the dihedral angles φ and ψ for those neighboring peptide combinations that satisfy a tetrahedral-angle geometry at the α-carbon (F.M. Marassi & S.J. Opella, unpublished results). The resulting sets of φ and ψ angles were analyzed for minimum energy by comparison with the Ramachandran map, and were classified as ‘core’, ‘allowed’, ‘generous’ or ‘outside,’ according to the PROCHECK data-base35. This procedure applied to residues 6–19 of AChR M2 yields 24 low-energy, ‘core,’ transmembrane α-helical solutions. The average of these 24 structures is shown (Fig. 4c, e, f).

Molecular modeling

Energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using the programs INSIGHT and DISCOVER (Biosym Technology, San Diego, CA), as described5,36. The coordinates of the helical backbone determined from the solid-state NMR measurements were utilized as templates for the bundle. The coordinates obtained from solution NMR were superimposed over those from solid-state NMR, in order to fix the M2 helix orientation in the lipid bilayer membrane. A pentameric, C5-symmetric, parallel array was then optimized using energy minimization and molecular dynamics with constraints to maintain C5 symmetry and helical backbone torsions. Pore contours were calculated using the program HOLE37.

Coordinates

The coordinates of the solution and solid state of NMR structures of the AChR M2 and NMDAR M2 have been submitted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB files 1A11, 2NR1 and 1cek).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Nelson for assistance with molecular modeling and the preparation of Fig. 5. We thank W. Sun and A. Ferrer-Montiel for their participation in the initial experiments. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to S.J.O and to M.M. This research utilized the Resource for Solid-State NMR of Proteins at the University of Pennsylvania, supported by a grant from the Biomedical Research Technology Program, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. F.M.M. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Medical Research Council of Canada. A.P.V. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from FAPESP-Brazil (Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo).

References

- 1.Colquhoun D, Sakmann B. From muscle endplate to brain synapses: a short history of synapses and agonist-activated ion channels. Neuron. 1998;20:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lena C, Changeux JP. Pathological mutations of nicotinic receptors and nicotine-based therapies for brain disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:674–682. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unwin N. Acetylcholine receptor channel imaged in the open state. Nature. 1995;373:37–43. doi: 10.1038/373037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oiki S, Madison V, Montal M. Bundles of amphipathic transmembrane α-helices as a structural motif for ion-conducting channel proteins: studies on sodium channels and acetylcholine receptors. Proteins. 1990;8:226–236. doi: 10.1002/prot.340080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuner T, Wollmuth LP, Karlin A, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Structure of the NMDA receptor channel M2 segment inferred from accessibility of substituted cysteines. Neuron. 1996;17:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollmann M, Maron C, Heinemann S. N-glycosylation site tagging suggests a three transmembrane domain topology for the glutamate receptor GluR1. Neuron. 1994;13:1331–1343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oblatt-Montal M, Buhler LK, Iwamoto T, Tomich JM, Montal M. Synthetic peptides and four-helix bundle proteins as model systems for the pore-forming structure of channel proteins. The transmembrane segment M2 of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor channel is a key pore lining structure. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14601–14607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Opella SJ. NMR and membrane proteins. Nat Struct Biol, NMR Suppl. 1997;4:845–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay LE, Ikura M, Tschudin R, Bax A. Three-dimensional triple resonance NMR spectroscopy of isotopically enriched proteins. J Magn Reson. 1990;89:496–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bax A, Ikura M. An efficient 3D NMR technique for correlating the proton and 15N backbone amide resonance with the alpha-carbon of the preceding residue in uniformly 15N/13C enriched proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1991;1:99–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01874573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wuthrich K. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opella SJ, Stewart PL. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance structural studies of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1989;176:242–275. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)76015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketchem RR, Hu W, Cross TA. High-resolution conformation of gramicidin A in a lipid bilayer by solid-state NMR. Science. 1993;261:1457–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.7690158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marassi FM, et al. Dilute spin-exchange assignment of solid-state NMR spectra of oriented proteins: acetylcholine M2 in bilayers. J Biomol NMR. 1999 doi: 10.1023/a:1008391823293. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doyle DA, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akabas MH, Kaufmann C, Archdeacon P, Karlin A. Identification of acetylcholine receptor channel lining residues in the entire M2 segment of the alpha subunit. Neuron. 1994;13:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galzi JL, et al. Mutations in the channel domain of a neuronal nicotinic receptor convert ion selectivity from cationic to anionic. Nature. 1992;359:500–505. doi: 10.1038/359500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charnet P, et al. An open channel blocker interacts with adjacent turns of α-helices in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1990;4:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90445-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gesell JJ, Opella SJ, Sun W, Montal M. Proc. 6th Symp. Protein Soc.; San Diego, CA. July 25–29, 1992; p. 52.p. abstr. s33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamoto T, Grove A, Montal MO, Montal M, Tomich JM. Chemical synthesis and characterization of peptides and oligomeric proteins designed to form transmembrane ion channels. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1994;43:597–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1994.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bax A, Griffey RH, Hawkins BL. Correlation of proton and nitrogen-15 chemical shifts by multiple quantum NMR. J Magn Reson. 1983;55:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piotto M, Saudek V, Sklenar V. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J Biomol NMR. 1992;2:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clore GM, Nilges M, Sukumaran D, Brunger A, Karplus M, Gronenborn A. The three-dimensional spectra of α1-purothiamin in solution: combined use of nuclear magnetic resonance, distance geometry and restrained molecular dynamics. EMBO J. 1986;5:2729–2735. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vuister GW, Bax A. Quantitative J correlation: a new approach for measuring homonuclear three-bond J(HNHα) coupling constants in 15N-enriched proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:7772–7777. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunger AT. X-PLOR version 3.1. a system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pines A, Gibby MG, Waugh JS. Proton-enhanced NMR of dilute spins in solids. J Chem Phys. 1973;59:569–590. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levitt MH, Suter D, Ernst RR. Spin dynamics and thermodynamics in solid-state NMR cross polarization. J Chem Phys. 1986;84:4243–4255. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu CH, Ramamoorthy A, Opella SJ. High resolution dipolar solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson A. 1994;109:270–272. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramamoorthy A, Wu CH, Opella SJ. Three-dimensional solid-state NMR experiment that correlates the chemical shift and dipolar coupling frequencies of two heteronuclei. J Magn Reson B. 1995;107:88–90. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marassi FM, Ramamoorthy A, Opella SJ. Complete resolution of the solid-state NMR spectrum of a uniformly 15N labeled membrane protein in phospholipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8551–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenneman MT, Cross TA. A method for the analytic determination of polypeptide structure using solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance: the metric method. J Chem Phys. 1990;92:1483–1494. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu CH, Ramamoorthy A, Gierasch LM, Opella SJ. Simultaneous characterization of the amide 1H chemical shift, 1H-15N dipolar coupling, and 15N chemical shift interaction tensors in a peptide bond by three-dimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6148–6149. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tycko R, Stewart PL, Opella SJ. Peptide plane orientations determined by fundamental and overtone 14N NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:5419–5425. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oblatt-Montal M, Yamazaki M, Nelson R, Montal M. Formation of ion channels in lipid bilayers by a peptide with the predicted transmembrane sequence of botulin neurotoxin A. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1490–1497. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smart OS, Goodfellow JM, Wallace BA. The pore dimensions of gramicidin A. Biophys J. 1993;65:2455–2460. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81293-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraulis P. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]