Abstract

The three-dimensional structures of membrane proteins are essential for understanding their functions, interactions and architectures. Their requirement for lipids has hampered structure determination by conventional approaches. With optimized samples, it is possible to apply solution NMR methods to small membrane proteins in micelles; however, lipid bilayers are the definitive environment for membrane proteins and this requires solid-state NMR methods. Newly developed solid-state NMR experiments enable completely resolved spectra to be obtained from uniformly isotopically labeled membrane proteins in phospholipid lipid bilayers. The resulting operational constraints can be used for the determination of the structures of membrane proteins.

Introduction

Determining the three-dimensional (3D) structures of membrane proteins at atomic resolution is fundamental to the understanding of many important biological functions, for example, those of drug receptors and ion channels. Because over a third of expressed polypeptides are predicted to be membrane associated, knowledge of their structures is also an essential part of deciphering the information from the various genome projects [1]. The two principal experimental methods for structure determination, X-ray crystallography and solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, work well for the globular proteins of the cytoplasm or periplasm, and have contributed more than 7 000 protein structures to the Brookhaven National Laboratories Protein Data Bank; however, the fact that only 1% of the protein structures in the Data Bank correspond to membrane proteins reflects the significant challenge posed by this class of molecules. At the heart of the problem is the presence of the essential lipids, which complicates the preparation of quality X-ray crystals and rapidly reorienting samples for multidimensional solution NMR studies.

Fortunately, NMR spectroscopy is a versatile and powerful approach to the study of macromolecular structure and dynamics. The ability to perform NMR experiments on either liquid or solid-phase samples, for example, provides the opportunity for structure determination of proteins in several membrane environments. In addition, the recent development of new expression systems, mutant cell strains, and the availability of new lipids for membrane protein reconstitution, have opened the field of structural biology to many membrane proteins that were previously unavailable for examination. The primary motivation for expressing membrane proteins in bacteria is the variety of isotopic labeling schemes that can be incorporated in the NMR experimental strategy. Bacterial expression allows both selective and uniform labeling, whereas synthesis only permits specific labeling at only one or a few sites in the protein. These advances, together with the parallel development of new pulse sequences, which take advantage of uniform isotopic labeling schemes for both solution and solid-state NMR, provide a powerful arsenal with which to tackle the problem of membrane protein structure determination. In this review, we discuss the most recent innovations that have placed NMR spectroscopy at the forefront as a method capable of determining the structure of membrane proteins.

Membrane proteins in micelles

In solution NMR spectroscopy, line-narrowing is achieved through rapid molecular reorientation, which averages the operative nuclear spin interactions to their isotropic values. Small lipid micelles provide an effective environment for the study of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy without the adverse effects of organic solvents that can denature proteins or distort their secondary structure by promoting helix formation. The preparation of homogeneous micelle samples has the primary goal of reducing the effective rotational correlation time of the incorporated protein so that resonances will have the narrowest achievable linewidths ([2,3,4••,5]; GL Veglia et al., unpublished data). This is a crucial step in solution NMR structural studies of membrane proteins, and several types of micelles are available, including those formed from sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) and diheptanoylphosphocholine (DHPC). These three lipids provide flexibility in the choice of headgroup and length and number of acyl chains. A number of additional factors contribute to the quality of the NMR spectra obtained from peptides and proteins in micelles. Optimal salt concentration, pH, temperature and lipid concentrations much higher than the critical micelle concentration are essential for preparing samples that yield NMR spectra with narrow linewidths and the appropriate number of resonances.

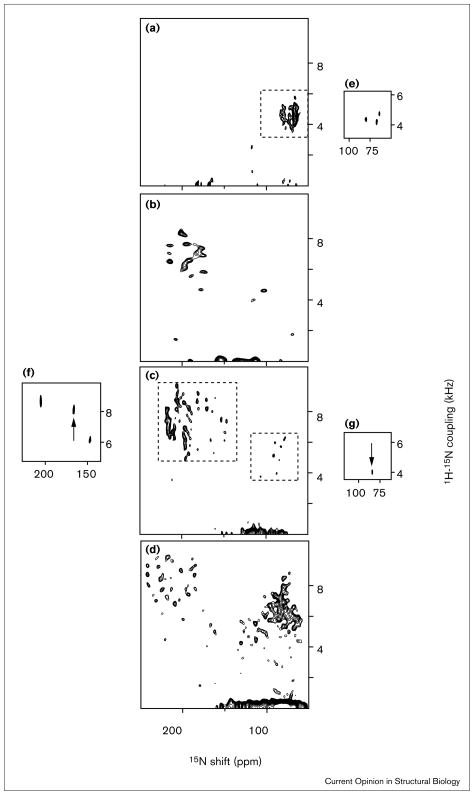

It is possible to utilize conventional multidimensional solution 1H-NMR experiments for the structure determination of small polypeptides in micelles; however, even for highly optimized micelle samples, solution NMR experiments of unlabeled peptides with more than about 25 residues are problematic due to broad lines and limited chemical shift dispersion. Although some progress has been made with unlabeled synthetic peptides, the spectra generally offer such limited resolution that all aspects of measurements and resonance assignments are difficult. Uniformly 15N labeled peptides, on the other hand, generally yield resolved two-dimensional (2D) 1H/15N heteronuclear correlation spectra in well-prepared micelle samples. The 1H/15N heteronuclear correlation spectra of five different uniformly 15N labeled membrane proteins, ranging in size from about 25 to 125 amino acids, are shown in Figure 1. In these spectra there is a single correlation resonance for each amide site or indole nitrogen of the tryptophan sidechains (GL Veglia et al., unpublished data).

Figure 1.

2D 1H chemical shift/15N chemical shift heteronuclear correlation spectra of uniformly 15N labeled proteins in micelles using solution NMR spectroscopy (GL Veglia et al., unpublished data). (a) Magainin (25 residues) in DPC. (b) Acetylcholine M2 peptide (25 residues) in DPC. (c) Major coat protein from fd bacteriophage (50 residues) in SDS. (d) Vpu from HIV-1 (81 residues) in DHPC. (e) MerT from the bacterial mercury detoxification system (122 residues) in SDS.

The spectra in Figure 1 demonstrate that it is possible to resolve nearly all amide resonances of uniformly 15N labeled 25–125 residue membrane proteins in micelles, despite the limited chemical shift dispersion exhibited by helical proteins. They provide a reference for most subsequent solution NMR experiments and the starting point for multidimensional double- and triple-resonance experiments used for making assignments and for measuring the distance, angular and relaxation parameters used to determine the structures and describe the dynamics of proteins in solution [6]. The resulting data also provide qualitative indicators of the secondary structure [7]; however, it is clear that the upper size limit for NMR structure determination of membrane proteins in micelles is considerably lower than it is for globular proteins in aqueous solution. Indeed, for membrane proteins with more than 50 residues, resonance assignments require uniform 2H as well as 13C and 15N labeling (GL Veglia et al., unpublished data). The application of multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy to samples of uniformly labeled recombinant membrane proteins incorporated in lipid micelles has produced the 3D structures of the M2 pore-lining segment of both the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) and N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channels [5,8••], the transmembrane domain of glycophorin A (GpA) [9••] and the major coat proteins from the bacteriophages fd [10,11••], Ike [12] and M13 [13,14].

Bicelles are an attractive alternative model membrane environment for NMR studies of membrane proteins. Because these are bilayer discs with both long and short chain phospholipids, they offer the opportunity to study membrane proteins in an environment that closely resembles the planar surface of biological membranes [15,16]. Bicelle discs orient in the field of the spectrometer magnet; therefore, it is possible to measure parameters containing long-range angular information, such as residual dipolar couplings. This is in contrast to micelle samples where such orientational information is lost because the spin interactions are averaged to their isotropic values. Because the NMR frequency dispersions afforded by oriented systems are wider than those from isotropic samples, they also offer the prospect of higher spectral resolution. In the case of small peptides, bicelles retain enough mobility for high resolution solution NMR spectroscopy. One example is the myristoylated N-terminal fragment of ADP-ribosylation factor 1, the structure of which has been characterized in lipid bicelles using solution NMR methods [17]. Measurements of the residual dipolar couplings and chemical shift anisotropies, from specifically 13C and 15N labeled peptides, were used to derive structural parameters for four planes in the peptide backbone. Alternatively, isotropic solutions of unoriented bicelles that retain the planar bilayer geometry have been used with conventional NMR spectroscopy for the structural characterization of the membrane surface helical peptide mastoparan [18]; however, the asymmetric shape and larger size of lipid bicelles may preclude their general application to solution NMR studies of membrane proteins.

Membrane proteins in bilayers

Phospholipid bilayers are the definitive environment for membrane proteins and solution NMR methods, which are hampered by the slow correlation times, fail completely; however, since solid-state NMR spectroscopy does not rely on rapid molecular reorientation for line narrowing, it is well suited for peptides and proteins immobilized in phospholipid bilayers. The 15N NMR spectrum in Figure 2d was obtained from an unoriented sample of uniformly 15N-labeled fd coat protein in phospholipid bilayers. Most of the backbone sites are structured and immobile on the timescale of the 15N chemical shift interaction (10 kHz) and contribute to the characteristic amide powder pattern between about 220 and 60 ppm. For comparison, Figure 2e shows the 15N chemical shift powder pattern, simulated for an immoblie, 15N labeled amide site, with its corresponding principal tensor elements σ11, σ22 and σ33. The spectrum of an unoriented bilayer sample with multiple-labeled sites provides no resolution among resonances, without additional sample or spectroscopic manipulations.

Figure 2.

1D 15N chemical shift solid-state NMR spectra of the 15N labeled fd coat protein in phospholipid bilayers (a–d). (e) Simulated powder pattern for a rigid 15N labeled amide site. The 15N amide chemical shift tensor elements σ11, σ22 and σ33, referenced to liquid ammonia at 0 ppm, are indicated. (a) Uniformly 15N labeled coat protein in magnetically oriented bicelles tilted to the parallel orientation with the addition of lanthanide ions [42]. (b) Selectively 15N leucine-labeled coat protein in oriented phospholipid bilayers [35••]. (c) Uniformly 15N labeled coat protein in oriented bilayers [35••]. (d) Uniformly 15N labeled coat protein in unoriented bilayer vesicles [35••]. The narrow resonance band centered at the isotropic frequency near 115 ppm results from backbone sites that are mobile and unstructured. The narrow peak near 30 ppm is from the amino groups of the lysine sidechains and the N terminus.

Solid-state NMR offers two complementary but independent approaches for high-resolution spectroscopy and structure determination of membrane proteins. Both methods utilize radiofrequency irradiations for line-narrowing and sensitivity enhancement [19,20]. One approach, which we are developing for membrane protein structure determination, takes advantage of the favorable spectroscopic properties exhibited by uniaxially oriented samples. Sample orientation gives narrow lines and well resolved, orientationally dependent spectra that can be used directly for structure determination [21–24]. In addition, it is possible to utilize dipole couplings to make distance measurements. The other solid-state NMR approach utilizes unoriented bilayer samples and relies on magic angle spinning (MAS) methods for spectral resolution and for the measurement of distances via homonuclear or heteronuclear dipolar interactions [25–27]. MAS narrows the resonances significantly and, in favorable cases, resolves individual resonances in proteins, albeit at the expense of the orientational information; however, resolution remains an important issue in MAS experiments and an analysis of the prospects for uniformly labeled proteins was rather pessimistic [28]. Recently, a number of new experiments have been described for the measurement of torsion angles from unoriented peptide samples, via MAS or static solid-state NMR spectroscopy [29•,30–33]. Both MAS and static solid-state NMR experiments on unoriented samples require samples labeled with stable isotopes only in one or a few selected sites. This not only makes the determination of complete structures laborious, but limits applications to peptides prepared by solid-phase synthesis, or small proteins with favorable distributions of amino acids, or selected regions of large proteins, limitations which are not present in the approach that utilizes oriented samples.

Solid-state NMR of oriented bilayer samples

When a uniaxially ordered, immobile sample is oriented with its single axis of symmetry parallel to the direction of the applied magnetic field, the resulting NMR spectra are characterized by single line resonances in all frequency dimensions. Because the observed resonance frequencies depend on the orientation of their respective molecular sites relative to the sample unique director axis, they provide the basis for a method of structure determination based on orientational constraints [5,22,34]. This method is independent of multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy, which relies instead on the properties of isotropic resonances observed from rapidly reorienting molecules. It also differs from the MAS experiments where the orientational dependence is lost by spinning the sample at the magic angle, and the spectra are characterized by isotropic average resonance frequencies.

The conventional approach is to prepare planar lipid bilayers on glass slide supports that are then oriented in the probe so that the bilayer normal is parallel to the field of the magnet [34,35••,36]. With homogeneous membrane protein reconstitution [35••] and precise sample alignment in the magnetic field, the use of high field magnets [37••,38] and wrapping the probe rf coil directly around a stacked glass slide sample [39], it is now possible to do NMR experiments on samples containing 1 mg or less of uniformly 15N-labeled protein. It is also possible to use bicelles that are magnetically oriented with their bilayer normal parallel to the field by the addition of small amounts of lanthanide ions [40]; these samples offer the advantage of having solutions containing immobilized oriented proteins and yielding solid-state NMR spectra as shown in Figure 2a [41].

The effect of orientation of a protein within the bilayer membrane is reflected in the one-dimensional solid-state 15N chemical shift NMR spectra of 15N labeled fd coat protein in oriented phospholipid bilayers (Figure 2b,c). In these spectra, each 15N resonance arises from a single nitrogen in the protein and has a frequency that reflects the orientation of the corresponding N–H bond in the lipid membrane. The spectrum in Figure 2c, obtained from an oriented sample of uniformly 15N labeled fd coat protein, displays significant resolution with identifiable peaks at frequencies throughout the range of the 15N amide chemical shift anisotropy powder pattern. There are two resonances in the spectrum of selectively 15N leucine labeled fd coat protein in oriented bilayers, corresponding to Leu41, near the σ33 end of the powder pattern, and Leu14, near the σ11 end (Figure 2b). The large 80 ppm frequency difference between the 15N leucine resonances demonstrates the effect of protein tertiary structure on these spectra. In an α helix, the amide N–H bonds align with the long helix axis, so that finding the N–H bonds oriented parallel to the bilayer normal implies that the helix is transmembrane. Thus, Leu41 in the transmembrane helix has its N–H bond approximately parallel to the field and to the σ33 component of the chemical shift tensor, whereas Leu14 in the amphipathic in-plane helix has its N–H bond perpendicular [10,11••]. In cases where the protein secondary structure has been established, the measurement of one or more orientation-ally dependent frequencies from a single labeled site provides valuable information regarding the topology of protein interaction with the membrane [42–45].

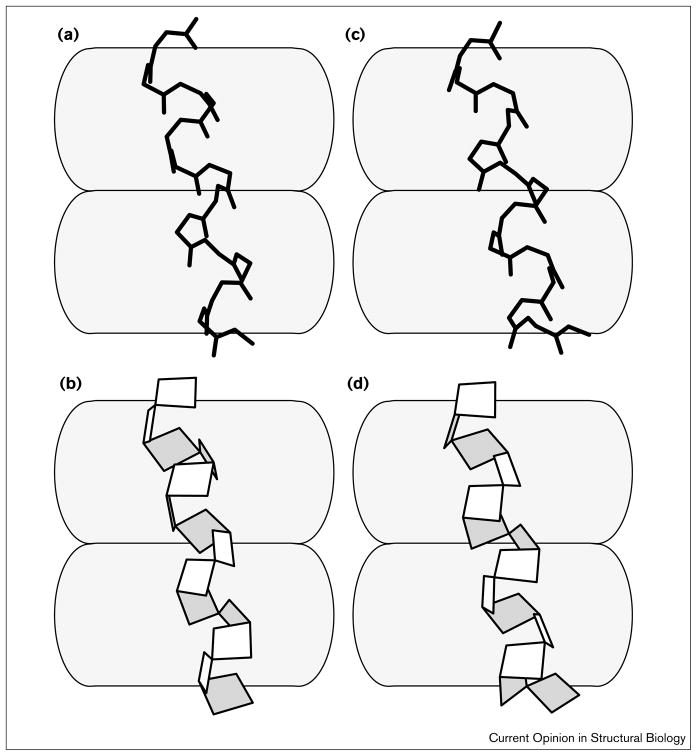

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy can be used to determine the 3D structures of membrane proteins in bilayers. The orientationally dependent 15N chemical shift, 1H chemical shift and 1H-15N dipolar coupling frequencies provide orientational constraints for the structure determination of 15N labeled peptides in lipid bilayer membranes, and can be measured directly from the 2D and 3D spectra of 15N labeled proteins in oriented bilayers. In the solid-state NMR spectra of oriented proteins, multiple frequency dimensions enable the simultaneous measurement of multiple orientational constraints, which are used for structure determination, and provide the means for resolving resonances in the spectra of uniformly labeled proteins. The 2D and 3D correlation spectra in Figure 3 of four uniformly 15N labeled proteins, ranging in size from 25 to 190 residues, in oriented lipid bilayers, have many resolved resonances. As shown for the 50-residue fd coat protein (Figure 3c,f,g), it is now possible to obtain completely resolved solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N labeled membrane proteins in oriented bilayers [35••]. This points to a crucial difference between solution and solid-state NMR experiments. For larger proteins, there will be additional resonances in both types of spectra; however, in solid-state NMR spectra, the increase in molecular mass is not accompanied by increased line widths, whereas in solution NMR spectra, larger molecular mass, corresponding to slower reorientation rates, leads to broader lines, more efficient spin diffusion and other deleterious effects. Complete 3D protein structures are assembled from the orientations of contiguous peptide planes determined using the angular constraints imposed by the measured spectral frequencies. The 3D structures of the gramicidin ion channel peptide [34] and of the M2 transmembrane segment of the AChR [5,8••] have been determined in oriented bilayers in this way.

Figure 3.

2D 15N chemical shift/1H-15N heteronuclear dipolar coupling spectral planes from 2D and 3D solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N labeled membrane proteins in oriented phospholipid bilayers. (a) Magainin. (b) Acetylcholine M2 peptide [5]. (c) Coat protein from the fd bacteriophage [35••]. (d) Colicin E1 [37••]. (a–d) are complete 2D PISEMA (polarization inversion with spin exchange at the magic angle) spectra. (e) Plane extracted from a 3D correlation spectrum of magainin at 15.7 ppm 1H chemical shift. (f) Plane extracted from a 3D correlation spectrum of fd coat protein at 11.0 ppm 1H chemical shift. The resonance assigned to Leu41 in the hydrophobic transmembrane helix is marked with the arrow. (g) Plane extracted from a 3D correlation spectrum of fd coat protein at 11.6 ppm 1H chemical shift. The resonance assigned to Leu14 in the amphipathic in-plane helix is marked with the arrow.

Magic angle spinning solid-state NMR of bilayer samples

In MAS, rapid sample rotation at the magic angle, 54.7° relative to the field of the spectrometer magnet, yields isotropic frequency spectra that contain no orientational information. Distance constraints are obtained through measurements of homonuclear or heteronuclear dipolar couplings. MAS experiments on unoriented bilayer samples are an important complementary strategy with considerable potential for membrane proteins [26]. In general, the use of unoriented samples has a number of attractive features. It eliminates a major step in sample preparation, although membrane proteins may be the one case where this is not a serious limitation; however, the application of MAS as a general method for the independent structure determination of membrane proteins requires improvements in both sensitivity and resolution. Dynamic nuclear polarization, in which polarization is transferred from unpaired electrons to uncoupled nuclear spins through microwave irradiation, offers dramatic gains in sensitivity and enhancements of signal to noise ratios up to 100 have been demonstrated in amino acids and proteins [46]. Photochemical-induced dynamic nuclear polarization has also been used with uniformly labeled photosynthetic reaction centers [47]. Low temperatures alone can provide substantial gains in sensitivity and make sample conditions more directly comparable with those used in diffraction experiments.

NMR structural studies of membrane proteins

Comparisons among results obtained in the various membrane environments serve as essential controls for the effects of the various lipids, relative influences of overall and local dynamics and the NMR experiments themselves.

Transmembrane domain of glycophorin A

GpA is the primary sialoglycoprotein in human erythrocyte membranes. Peptides with sequences that correspond to the transmembrane domain, corresponding to residues 62–101 of GpA, have been studied in micelles and unoriented bilayers by NMR spectroscopy. The results from both types of NMR structural studies are in good agreement regarding the features of the dimer interface. The peptides form dimers and the packing geometry has been characterized by measuring distances between specifically labeled methyl groups on sequential residues around one helical turn and backbone carbonyl groups on the other helix with rotational resonance solid-state NMR experiments [48]. The 3D structure of the expressed peptide, corresponding to the same region, has been recently determined in DPC micelles by solution NMR methods [9••]. Residues 73–96 of the GpA peptide form an α helix. Each dimer is symmetric, with helices crossing at an angle of –40°, forming a small interface that lacks intermonomer hydrogen bonds, but is mediated by van der Waals’ interactions. This structure provides the information necessary to understand the basis of sequence-dependent GpA dimerization.

Magainin

Magainin is a 23-residue antibiotic peptide. Perhaps because it is water soluble and surface associated, the solution NMR results are consistent in showing that it is fully helical in DPC and SDS micelles, and trifluoroethanol/water mixtures [49]. Solid-state NMR experiments on oriented bilayer samples also show that the peptide is α helical, and that the helix axis is in the plane of the bilayer, information that could never be obtained from solution samples [42]. These earlier studies focused on synthetic specifically 15N labeled peptides, which limited the investigation to specific regions of the peptide. Uniform 15N labeling offers the opportunity for complete independent structure determination. The 3D solid-state NMR spectrum of uniformly 15N labeled magainin in bilayers is fully resolved (Figure 3a). The presence of a single resonance for each amide site demonstrates that the peptide adopts a unique conformation along its entire length and orients uniformly parallel to the membrane surface. In contrast, distance measurements made on unoriented bilayer samples with MAS experiments [50] were interpreted to show that residues 15–19 have one-third β sheet and two-thirds α helix secondary structure. The difference between the results obtained on oriented bilayer samples, which show only α helix, and those from unoriented samples, which show a mixture of secondary structures, may be explainable by differences in the peptide-to-lipid ratios of the samples.

M2 peptides from the acetylcholine receptor

The sequences of the second transmembrane segment, M2, of the AChR and other neurotransmitter-gated channels are highly conserved and believed to be responsible for their channel activity. The 25-residue AChR M2 peptide was expressed and shown to be completely helical in both micelles and bilayers [5,8••] (Figure 4). Although both solution and solid-state NMR methods yield 3D structures with atomic resolution, solid-state NMR on oriented lipid bilayer samples is unique in providing the complete molecular topology, including 3D structure and orientation, of the peptide in the membrane, at atomic resolution. The AChR M2 peptide is a transmembrane α helix with its long helix axis tilted 12° relative to the lipid bilayer normal. The helix is rotated about its long axis so that a pentamenic arrangement of the M2 peptides in the bilayer forms a funnel-like channel, with its wide mouth at the N terminus. This is a crucial element of membrane protein structure, and, in the case of AChR M2, sheds light on the details of supramolecular channel architecture.

Figure 4.

Average structures of the AChR M2 peptide calculated from solution NMR distance constraints (a,b) and from the solid-state NMR orientational constraints obtained from the 2D spectrum shown in Figure 2b (c,d) [5,8••]. Both structures are shown in the bilayer membrane in the exact orientation determined from solid-state NMR. The helix long axis is tilted approximately 12° from the membrane normal. The backbone structure of a protein can be described equivalently by vectors representing bonds between nonhydrogen atoms, as by the peptide planes formed by the individual rigid peptide bonds and their directly bonded atoms. Both representations of the M2 peptide backbone are shown. (a,c) Peptide plane representations with the N–H bonds highlighted. (b,d) Vector representation including the C–O bonds.

Although most of the resonances in the 2D spectrum of AChR M2 (Figure 3b) were assigned to specific residues through comparisons with 2D spectra from selectively 15N labeled recombinant peptides, and specifically 15N labeled synthetic peptides, significantly, a number of resonances were assigned with 15N dilute spin-exchange experiments that provide a general assignment strategy for solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly 15N labeled proteins [5].

Major coat protein from fd bacteriophage

The 50-residue major coat protein of the filamentous fd bacteriophage is stored within the membrane of infected Escherichia coli bacterial cells before incorporation into virus particles as it is extruded through the membrane. The structure of the membrane-bound form of this protein has been determined in SDS micelles by solution NMR spectroscopy [10,11••]. Both solution NMR experiments on micelle samples and solid-state NMR experiments on oriented bilayer samples [10,35••] agree in showing that the protein has two distinct α-helical segments, a short amphipathic helix that lies in the plane of the membrane (residues 7–16) and a longer hydrophobic membrane spanning helix (residues 29–44).

Conclusions

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy is on the verge of joining X-ray crystallography and multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy as a third method of protein structure determination. Significantly, it is especially well suited to determining the structures of membrane proteins in bilayers. In the light of recent promising results on 25–200 residue polypeptides in bilayers, structure determination of membrane proteins with 300–400 residues and seven trans-membrane helices may be feasible in the near future. Because the functions of these proteins reflect the interplay among structure, dynamics and the asymmetric bilayer environment, phospholipid bilayers will always be the most pertinent samples for membrane protein structure determination. There will always be outstanding questions regarding the influence of a micellar environment on protein structure; however, in light of the scarcity of crystal structures for smaller membrane proteins, solution NMR structures from micelle samples serve as valuable comparisons with the initial solid-state NMR structures from bilayer samples. The slow reorientation rates of larger polypeptides in micelles impose severe limitations on solution NMR methods. The recent activity in the development of new MAS experiments indicates that the prospects for measuring distances and torsion angles in specifically labeled samples in bilayers are excellent; however, it is not clear how resolution can be improved enough for applications to uniformly labeled protein samples. It may be that this approach will make its greatest contributions through the accurate measurements of selected distances or angles in protein systems too large or complex for other methods [27,51•,52].

The future of the structure determination of oriented membrane proteins by solid-state NMR spectroscopy is bright. Proteins in bilayers are immobilized by their interactions with lipids and highly oriented samples can be prepared for the most powerful experiments. The completely resolved spectra of uniformly 15N labeled membrane proteins in bilayers demonstrate that there is no fundamental size limitation for NMR experiments performed in this way. These experiments are still at an early stage of development and we anticipate that better resolution will be observed with further advances in NMR spectroscopy and technology, especially the use of very high field magnets.

Acknowledgments

We thank our collaborators M Montal and M Zasioff for their important roles in the studies of M2 peptides and magainin, respectively. Our research is supported by grants from The National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM29754, R37 GM24266, PO1 GM56538 and RO1 AI20770), The Department of Energy (DE-FG07-97ER 62314) and The Environmental Protection Agency (R823576). It utilized the Resource for Solid-State NMR of Proteins at the University of Pennsylvania, supported by grant P41RR09731 from the Biomedical Research Technology Program, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. FM Marassi was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (153304-1994) and the Medical Research Council of Canada (9304FEN-1004-43344).

Abbreviations

- 1D

one-dimensional

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- DHPC

diheptanoylphosphocholine

- DPC

dodecylphosphocholine

- GpA

glycophorin A

- MAS

magic angle spinning

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Contributor Information

Francesca M Marassi, Email: fmarassi@wistar.upenn.edu.

Stanley J Opella, Email: opella@chestnut.chem.upenn.edu.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Fraser CM, Gocayne J, White O, Adams M, Clayton R, Fleischmann R, Bult C, Kerlavage A, Sutton G, Kelley J, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opella SJ, Kim Y, McDonnell PA. Experimental NMR studies of membrane proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:536–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonnell PA, Opella SJ. Effect of detergent concentration on multidimensional solution NMR spectra of membrane proteins in micelles. J Magn Reson. 1993;B102:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Opella SJ. NMR and membrane proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:845–848. A recent critique of the field of NMR spectroscopy applied to membrane protein structure determination. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marassi FM, Gesell JJ, Opella SJ. Recent developments in multidimensional NMR methods for structural studies of membrane proteins. In: Berliner L, Krishna NR, editors. Biological Magnetic Resonance. Vol. 6. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wuthrich K. NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8••.Opella SJ, Gesell J, Valente AP, Marassi FM, Oblatt-Montal M, Sun W, Ferrer-Montiel A, Montal M. Structural studies of the pore-lining segments of neurotransmitter-gated ion channels. Chemtracts-Biochem Molec Biol. 1997;10:153–174. The 3D structure and topology of the membrane insertion of a peptide corresponding to the M2 segment of the AChR was determined by oriented 2D solid-state NMR spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 9••.MacKenzie KR, Prestegard JH, Engelman DH. A transmembrane helix dimer: structure and implications. Science. 1997;276:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.131. The high-resolution structure of this dimeric transmembrane peptide was determined by solution NMR spectroscopy in micelles. Helix–helix contacts are mediated by van der Waals’ interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonnell PA, Shon K, Kim Y, Opella SJ. fd coat protein in membrane environments. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:447–463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11••.Almeida F, Opella SJ. fd coat protein structure in membrane environments: structural dynamics of the loop between the hydrophobic transmembrane helix and the amphipathic in-plane helix. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:481–495. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1114. The high-resolution structure of the fd major coat protein was determined in SDS micelles and the dynamics were described by 15N relaxation measurements. The structural and dynamic details of the connecting loop are described. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams KA, Farrow NA, Deber CM, Kay LE. Structure and dynamics of bacteriophage Ike major coat protein in MPG micelles by solution NMR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5145–5157. doi: 10.1021/bi952897w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry GD, Sykes BD. Assignment of 1H and 15N NMR resonances in detergent solubilized M13 coat protein: a model for the coat protein dimer. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5284–5297. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van de Ven FJM, Os JWM, Aelen JMA, Wymenja SS, Remerowski ML, Konings RNH, Hilbers CW. Assignment of 1H, 15N and backbone 13C resonances in detergent-solubilized M13 coat protein via multinuclear multidimensional NMR: a model for the coat protein monomer. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8322–8328. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders CR, Hare B, Howard KP, Prestegard JH. Magnetically-oriented phospholipid micelles as a tool for the study of membrane-associated molecules. Progr NMR Spectrosc. 1993;26:421–444. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders CR, Landis GC. Reconstitution of membrane proteins into lipid-rich bilayered mixed micelles for NMR studies. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4030–4040. doi: 10.1021/bi00012a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Losonczi JA, Prestegard JH. Nuclear magnetic resonance characterization of the myristoylated, N-terminal fragment of ADP-ribosylation factor 1 in a magnetically oriented membrane array. Biochemistry. 1998;37:706–716. doi: 10.1021/bi9717791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vold RR, Prosser RS, Deese AJ. Isotropic solutions of phospholipid bicelles: a new membrane mimetic for high-resolution NMR studies of polypeptides. J Biomol NMR. 1997;9:329–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1018643312309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waugh JS, Huber LM, Haeberlen U. Approach to high-resolution NMR in solids. Phys Rev Lett. 1968;20:180–182. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pines A, Gibby MG, Waugh JS. Proton-enhanced NMR of dilute spins in solids. J Chem Phys. 1973;59:569–590. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Opella SJ, Waugh JS. Two-dimensional 13C NMR of highly oriented polyethylene. J Chem Phys. 1997;66:4919–4924. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opella SJ, Stewart PL, Valentine KG. Protein structure by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Q Rev Biophys. 1987;19:7–49. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross TA, Opella SJ. Solid-state NMR structural studies of peptides and proteins in membranes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:574–581. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramamoorthy A, Marassi FM, Opella SJ. Applications of multidimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy to membrane proteins. In: Jardetzky O, Lefevre J, editors. Dynamics and the Problem of Recognition in Biological Macromolecules. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 237–255. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths JM, Griffin RG. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for measuring dipolar couplings in rotating solids. Anal Chim Acta. 1993;283:1081–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SO, Ascheim K, Groesbeek M. Magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy of membrane proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 1996;29:395–449. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDowell LM, Schaefer J. High-resolution NMR of biological solids. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:624–629. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tycko R. Prospects for resonance assignments in multidimensional solid-state NMR spectra of uniformly labeled proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:239–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00410323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Feng X, Verdegem PJE, Lee YK, Sandstrom D, Eden M, Bovee-Geurts P, de Grip WJ, Lugtenburg J, de Groot HJM, Levitt MH. Direct determination of a molecular torsion angle in the membrane protein rhodopsin by solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6853–6857. The H–C10–C11–H torsional angle of the retinylidene chromophore is determined and found to deviate from the planar conformation with an accuracy within 10°. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara T, Shimomoura T, Akutsu H. Multidimensional solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance for correlating anisotropic interactions under magic angle spinning conditions. J Magn Reson. 1997;124:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishii Y, Terao T, Kainosho M. Relayed anisotropy correlation NMR: determination of dihedral angles in solids. Chem Phys Lett. 1996;256:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(98)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt-Rohr K. Torsion angle determination in solid 13C-labeled amino acids and peptides by separated-local-field double-quantum NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7601–7603. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weliky DP, Tycko R. Determination of peptide conformation by two-dimensional magic angle spinning NMR exchange spectroscopy with rotor synchronization. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8487–8488. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ketchem RR, Hu W, Cross TA. High-resolution conformation of gramicidin A in a lipid bilayer by solid-state NMR. Science. 1993;261:1457–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.7690158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Marassi FM, Ramamoorthy A, Opella SJ. Complete resolution of the solid-state NMR spectrum of a uniformly 15N-labeled membrane protein in phospholipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8551–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8551. Complete resolution of the resonances in this 50-residue protein in bilayers is achieved through the use of 3D 15N shift/1H-15N dipolar coupling/1H shift correlation solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The orientations of the amide planes from the two leucines are assigned. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grobner G, Taylor A, Williamson PTF, Choi G, Glaubitz C, Watts JA, de Grip WJ, Watts A. Macroscopic orientation of natural and model membranes for structural studies. Anal Biochem. 1997;254:132–138. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37••.Kim Y, Valentine K, Opella SJ, Schendel SL, Cramer WA. Solid-state NMR studies of membrane-bound closed state of the colicin E1 channel domain in lipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 1998;7:342–348. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070214. Individual resonances are resolved in the 2D solid-state NMR spectrum of this 190-residue colicin E1 segment. This is the largest polypeptide to be characterized by solid-state NMR in oriented bilayers. The data confirm the ‘umbrella model’ for the interaction of colicin with the membrane. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotten M, Soghomonian VG, Hu W, Cross TA. High resolution and high fields in biological solid-state NMR. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 1997;9:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(97)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bechinger B, Opella SJ. Flat coil probe for NMR spectroscopy of oriented membrane samples. J Magn Reson. 1991;95:585–588. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prosser RS, Hunt SA, DiNatale JA, Vold RR. Magnetically aligned membrane model systems with positive order parameters: switching the sign of Szz with paramagnetic ions. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:269–270. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard KP, Opella SJ. High resolution solid-state NMR spectra of integral membrane proteins reconstituted into magnetically oriented phospholipid bilayers. J Magn Reson. 1996;B112:91–94. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bechinger B, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. Structure and dynamics of the antibiotic peptide magainin in membranes by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 1993;2:2077–2084. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovacs FA, Cross TA. Transmembrane four-helix bundle of influenza A M2 protein channel: structural implications from helix tilt and orientation. Biophys J. 1997;73:2511–2517. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78279-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bechinger B, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. Structure and orientation of the antibiotic peptide PGLa in membranes by solution and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biophys J. 1998;74:981–987. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74021-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grobner G, Choi G, Burnett IJ, Glaubitz C, Verdegem PJE, Lugtenburg J, Watts A. Photoreceptor rhodopsin: structural and conformational study of its chromophore 11-cis retinal in oriented membranes by deuterium solid-state NMR. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall DA, Maus DC, Gerfen GJ, Inati SJ, Becerra LR, Dahlquist FW, Griffin RG. Polarization-enhanced NMR spectroscopy of biomolecules in frozen solutions. Science. 1997;276:930–932. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zysmilich MG, McDermott A. Photochemically induced nuclear spin polarization in bacterial photosynthetic reaction centers: assignments of the 15N SSNMR spectra. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5867–5873. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith SO, Bormann BJ. Determination of helix–helix interactions in membranes by rotational resonance NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:488–491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gesell JJ, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. Two-dimensional 1H NMR experiments show that the 23-residue magainin antibiotic peptide is an -helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles, sodium dodecylsulfate micelles, and trifluoroethanol/water solution. J Biomol NMR. 1997;9:127–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1018698002314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirsch D, Hammer J, Maloy W, Blazyk J, Schaefer J. Secondary structure and location of magainin analogue in synthetic phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12733–12741. doi: 10.1021/bi961468a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Wang J, Balazs YS, Thompson LK. Solid-state REDOR NMR distance measurements at the ligand site of a bacterial chemotaxis membrane receptor. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1699–1703. doi: 10.1021/bi962578k. The ligand binding site of the serine receptor was characterized through distance measurements from 15N serine bound to 1-13C phenylalanine in the receptor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Middleton DA, Robins R, Feng X, Levitt MH, Spiers ID, Schwalbe CH, Reid DG, Watts A. The conformation of an inhibitor bound to the gastric proton pump. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]