Abstract

Objective

To determine how to use the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI) to classify patients according to disease severity (mild, moderate, and severe) and to identify which patients respond to therapy.

Design

Cohort

Setting

The connective-tissue disease clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

Patients

75 patients with clinical or histopathologic evidence of CLE or SLE were included in the study.

Interventions

None

Main Outcome Measures

The CLASI, Skindex-29, and the physician’s subjective assessment of severity and improvement were completed at every visit.

Results

Disease severity was assessed with 45 patient-visits. Mild, moderate, and severe disease corresponded with CLASI activity score ranges of 0–9, 10–20, and 21–70, respectively. Improvement in disease activity was assessed in 74 patients. A clinical improvement was associated with a mean 3-point or 18% decrease in the CLASI activity score. However, ROC analysis demonstrated an increased percentage of subjects correctly classified when a 4-point (sensitivity 39%, specificity 93%, correctly classified 76%) or 20% (sensitivity 46%, specificity 78%, correctly classified 67%) decrease in the CLASI activity score was used instead to identify improvement.

Conclusions

The CLASI can be used to categorize patients into severity groups and to identify clinically significant improvements in disease activity.

Introduction

The Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI) is a clinical tool that quantifies disease activity and damage in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The activity score is based on the degree of erythema, scale, mucous membrane lesions, and non-scarring alopecia1. Unlike other outcome measures in dermatology, CLASI scores are not based solely on the area of involved skin; rather, parts of the body that are most visible are weighted more heavily than those that are usually covered1. The CLASI has already been shown to have good content validity, addressing the most relevant aspects of CLE as determined by an expert panel of dermato-rheumatologists1. It also has good inter-rater and intra-rater reliability when used by either dermatologists or rheumatologists1, 2. Early small clinical studies have demonstrated responsiveness in all subsets of CLE, including individual lesions, localized and generalized DLE, as well as SCLE and tumid LE3–7.

In 2005, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated their guidelines regarding the development of new therapeutic agents for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)8. They recommended focusing on organ-specific therapies, which may be easier to approve than medications that target multiple organ systems. In order to demonstrate efficacy in one organ system, it is important to have an organ-specific index of disease activity and to understand how to use that index to characterize disease severity and define improvement. Therefore, we sought to determine how the CLASI activity score could be used to categorize patients into mild, moderate, and severe disease groups, as well as the change in the CLASI activity score that corresponds with a clinically significant improvement in disease activity.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients were recruited from our connective tissue disease clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of CLE based on the modified Gilliam9. All subjects were age 18 years or older. The study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB), and all patients were enrolled with IRB-approved informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act forms.

Outcome measures

Procedures

Several questionnaires were completed at each visit; the principle investigator completed the Physician’s Subjective Assessment of Severity, the Physician’s Subjective Assessment of Improvement, and the CLASI. The study subject completed the Skindex-29. These questionnaires are described in detail below.

The Physician’s Subjective Assessment of Severity (PSAS)

Subjects were categorized as having mild, moderate, or severe disease by the principle investigator, based on her subjective assessment of disease activity.

Skindex-29

Skin-specific quality of life was measured with the previously validated Skindex-2910. This questionnaire consists of 29 items, which are used to calculate three subscales: symptoms, emotions, and functioning. The symptoms scale measures the physical burden of the disease, such as pain, itch, burning, or sensitivity. The emotions scale measures the psychiatric effects of the disease, such as depression, anxiety, embarrassment, or anger. The functioning subscale focuses on the changes to daily life, such as work, sleep, and relationships with others. Each question ranges from 0–100 points, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life. Subscale scores were calculated based on the mean scores of the individual questions that comprise the subscale.

The Physician’s Subjective Assessment of Improvement

At clinic visits, the principle investigator categorized disease activity in each patient as improved, unchanged, or worse since the last visit. These assignments were based on the physician’s subjective assessment of the patient’s skin disease.

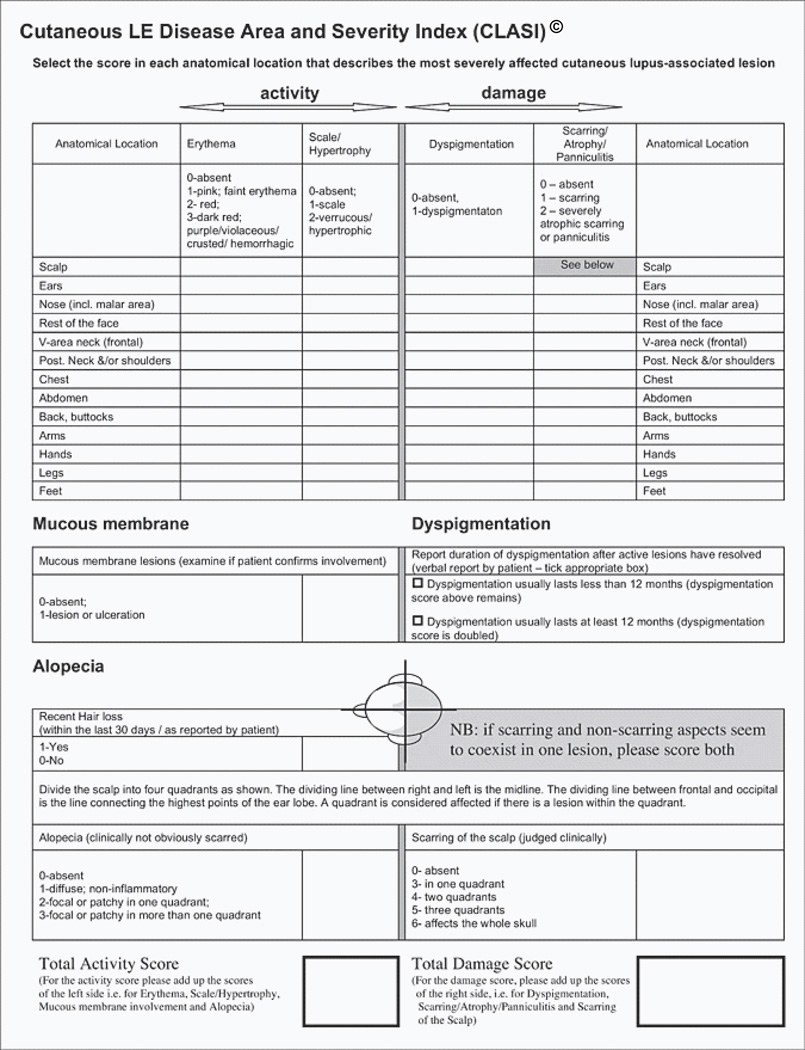

CLASI

Disease activity was measured using the CLASI activity score. This score ranges from 0–70, with higher scores indicating more severe skin disease (figure 1).

Figure 1. The CLASI.

The Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area an Severity index. Reprinted by permission for the University of Pennsylvania, copyright 2009.

Severity analysis

Study patients seen between November 2008 and April 2009 were classified by the principle investigator as having mild, moderate, or severe disease based on the degree of disease activity, as described above. Corresponding CLASI activity scores were also calculated. The optimal CLASI activity score ranges that corresponded with each severity group were determined by inspection of the CLASI score-by-PSAS crosstab row percents and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Using the crosstab row percents, it was determined how frequently a particular CLASI score was associated with each severity group. The CLASI cut-off score for each severity group was determined when three consecutive CLASI scores were associated most frequently with the same severity group. Two ROC analyses were employed to assess the merits of the CLASI cut-points suggested by the crosstab, one for mild disease (mild vs. moderate and severe) and one for severe disease (severe vs. moderate and mild). The CLASI scores that fell between the upper limit of mild and the lower limit of severe were designated as moderate.

Quality of life analysis

Study patients seen between January 2007 and June 2009 were included in the quality of life analysis. Quality of life, as indicated by Skindex-29 scores, was then compared between patients in each CLASI severity range using trend analysis, Spearman Correlations, and GLM-ANOVA. Quality of life was assessed in terms of mean Skindex-29 scores and the linear relationship between CLASI severity levels and quality of life.

Responsiveness analysis

In study patients seen between August 2008 and October 2009, disease activity was classified by the principle investigator as improved, unchanged, or worse compared to the previous visit, as described above. Those classified as improved were considered responders and those classified as unchanged or worse were considered non-responders. The CLASI activity score associated with a clinical improvement was estimated by calculating the mean signed change and percent change in CLASI activity scores for each group. When the baseline CLASI activity score was zero, 0.5 points were added to each score to allow the percent change to be calculated. Additionally, all outlier percent change scores, defined as more than ±500% in magnitude, were excluded from the analysis. If a subject had more than one set of consecutive visits in either the responder or non-responder group, the mean change in the CLASI activity scores was calculated such that the subject was only included once per category in the final analysis.

A ROC analysis was done to determine the sensitivity (the likelihood that a patient has a given delta CLASI given that he/she is a true responder), specificity (the likelihood that a patient does not have a given delta CLASI given that he/she is not a true responder), and percentage of patients correctly classified for each signed change and percent change in the CLASI activity scores. The final signed change and percent change CLASI scores associated with a clinical improvement were chosen based on the average signed change and percent change CLASI scores derived by responders and then confirmed by assessing the ROC operating characteristics at and around that cut-off, focusing primarily on the classification rate. All analyses were conducted using Stata MP version 11.0 (StataCorp) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc.)

Results

Patient characteristics

187 patients were enrolled in the study; of these, 74 had at least two visits recorded and completed the appropriate questionnaires and were included in the responsiveness analysis. A subset of these patients (n=37) was assessed with the PSAS and was included in the severity analysis. Of these, one subject did not have consecutive visits recorded and was excluded from the responsiveness analysis. Another subset of these patients (n=65) completed the Skindex-29 and was included in the quality of life analysis. In all, 75 patients were included in this analysis. The population was mostly female (89%) or Caucasian (64%), with a mean age of 48 years. A number of different CLE subtypes was represented, the most common including generalized discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE, 23%), localized DLE (24%), and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE, 31%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

75 subjects were included in the analysis. Of these, 1 subject did not have consecutive visits recorded and was therefore included in the severity analysis but not the responsiveness analysis. Subjects diagnosed with more than one lupus subtype were counted more than once under “diagnosis”.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 | 11 | |

| Female | 67 | 89 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American | 22 | 29 | |

| Caucasian | 48 | 64 | |

| Asian | 4 | 5 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | <1 | |

| Age | 48 years (mean) | - | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Discoid (generalized) | 17 | 23 | |

| Discoid (localized) | 18 | 24 | |

| Tumid | 8 | 11 | |

| Panniculitis | 5 | 7 | |

| SCLE | 23 | 31 | |

| ACLE | 12 | 16 | |

| Other | 9 | 12 |

Severity analysis

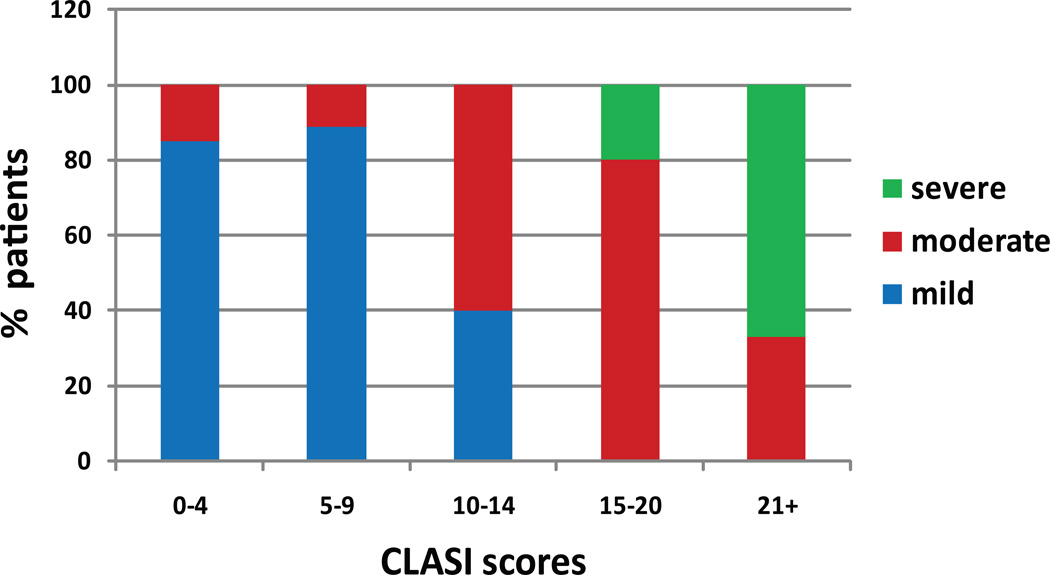

37 patients were classified by the principal investigator as having mild, moderate, or severe disease and corresponding CLASI activity scores were calculated. The number of visits ranged from 1 to 3, for a total of 45 different assessments. Overall, 60% of the patient-visits were mild, 29% were moderate, and 11% were severe. The crosstabs suggested a maximum CLASI activity score of 9 points for mild disease (sensitivity 93%, specificity 78%, 87% correctly classified) and 20 points for moderate disease (sensitivity 80%, specificity 95%, 93% correctly classified) (data not shown). Among the patients with CLASI activity scores between 0 and 9, 86% of had mild disease, 14% had moderate disease and 0% had severe disease. Between 10 and 20, 20% of patients had mild disease, 70% had moderate disease, and 10% had severe disease. Between 21 and 70, 0% of the patients had mild disease, 33% had moderate disease, and 67% had severe disease (Figure 2).

Figure 2. CLASI scores according to disease severity.

For a given range of CLASI scores, the percentage of patients within each category of disease severity was calculated.

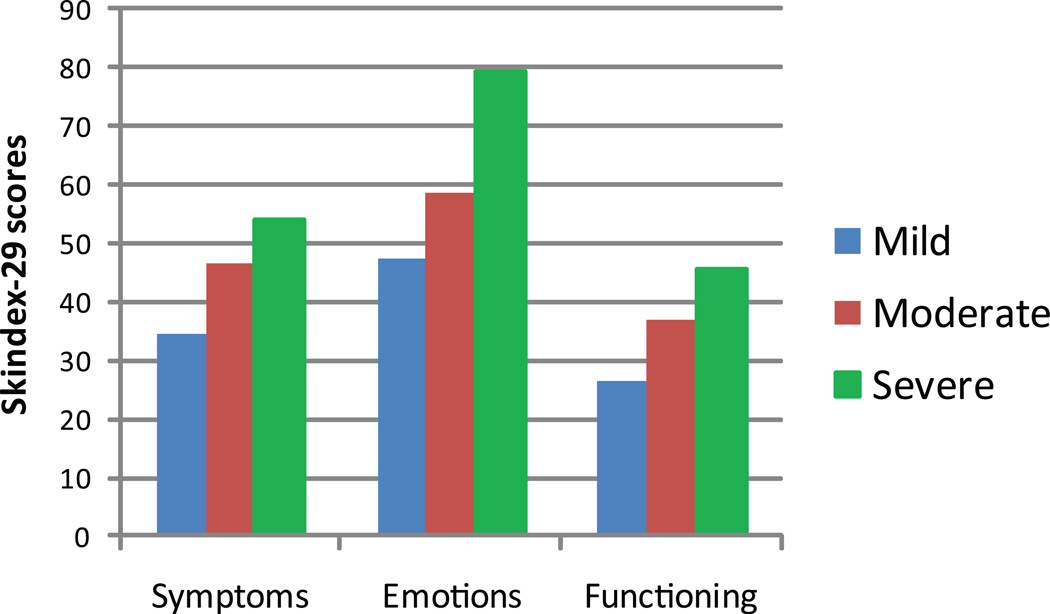

Mean Skindex-29 scores were calculated for patients in each severity group, as defined by CLASI activity scores. Quality of life became statistically significantly more impaired as disease severity increased (mild vs. severe: symptoms rsp= 0.33, p<0.008; FGLM= 3.42, p=0.0392); (mild vs. severe: emotions rsp = 0.35, p<0.0050; FGLM= 4.73, p=0.0123); (mild vs. severe: functioning rsp = 0.29, p< 0.0193; FGLM= 1.95, p=0.1516), indicating strong convergent validity between the CLASI severity classifications and quality of life measure (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Quality of life and disease severity.

Skindex-29 scores were calculated for each subject at the initial visit. Subjects were divided into severity groups based on CLASI scores. Skindex-29 sub-scores increased with worsening disease severity, indicating strong convergent validity between the CLASI severity classifications and quality of life measures.

Responsiveness analysis

74 subjects were included in the responsiveness analysis. Of these, there were 59 instances of non-responsiveness and 28 instances of responsiveness, for a total of 87 assessments. Overall, the prevalence of a clinically significant improvement was 32%.

The mean decrease in the CLASI activity score for responders and non-responders was 3.2 and −0.3 points, respectively. An ROC analysis indicated that a 3-point change in the CLASI activity score was 50% sensitive and 83% specific for improvement, resulting in 72% of patients being correctly classified as responders or non-responders. However, a 4-point change in the CLASI activity score had better specificity (93%), resulting in 76% of patients being correctly classified as having improved or not improved (Table 2a).

Table 2. Responsiveness.

For each CLASI change score (A, Δ CLASI) and % change score (B, % Δ CLASI) the sensitivity, specificity, and percentage of patients correctly classified were calculated. The numbers shown are based on the calculated mean Δ CLASI and % Δ CLASI that corresponded with a clinical improvement, as well as the adjacent scores. Within the % Δ CLASI group, there were no patients with an 18- or 19-point change, therefore 10, 17, and 20 are shown instead.

| A. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Δ CLASI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | % Correctly Classified |

| 2 | 57.14 | 79.66 | 72.41 |

| 3 | 50.00 | 83.05 | 72.41 |

| 4 | 39.29 | 93.22 | 75.86 |

| B. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Δ CLASI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | % Correctly Classified |

| 10 | 50.00 | 70.69 | 63.95 |

| 17 | 50.00 | 72.41 | 65.12 |

| 20 | 46.43 | 77.59 | 67.44 |

Similarly, the adjusted mean percent decrease in the CLASI activity score for responders and non-responders was 18% and −12%, respectively. An ROC analysis indicated that the percentage of patients correctly classified was optimized when using a 20% decrease in the CLASI activity score to detect improvement, which has 46% sensitivity, 78% specificity, and 67% correct classification (Table 2b).

Discussion

These results indicate that the CLASI can be used to categorize patients into severity groups, with activity scores of 0–9 indicating mild disease, 10–20 indicating moderate disease, and 21–70 indicating severe disease. It is also a useful tool in determining whether or not patients responded to treatment, as patients who improved clinically had a mean 3-point or 18% decrease in their CLASI activity scores. However, the ROC analysis suggests that the percentage of patients correctly classified can be optimized by using a 4-point or 20% decrease in the CLASI activity score to identify improvement.

Earlier studies have suggested that the CLASI is responsive to changes in disease activity; members of our group followed eight CLE patients (7 DLE, 1 SCLE) for 56 days following the initiation of a new therapy and found that decreases in the CLASI activity score correlated well with improvements in the physician’s global skin assessment, the patient’s global skin assessment, and the pain score3. Similarly, Kreuter et al has demonstrated that CLASI activity scores decrease significantly in patients with tumid LE following three months of therapy with an antimalarial medication5. He has also shown that CLASI activity scores decrease significantly in patients with refractory SCLE after therapy with mycophenolate sodium, which correlates with objective signs of improvement on ultrasound and colorimetry6. Finally, Erceg et al has illustrated a significant decrease in CLASI activity scores in patients with DLE following pulsed dye laser therapy4. While these studies imply that the CLASI is sensitive to improvement, this is the first study to systematically determine the minimal change in the CLASI that corresponds to a meaningful clinical improvement.

For both the signed change and percent change analyses, there was a clear difference in the mean CLASI scores of the responders and non-responders, indicating that the CLASI is sensitive to improvement. The mean change in the CLASI score for the non-responders, particularly with respect to percent change, was negative; this is likely due to the fact that the non-responder group included patients with both stable and worsening disease activity.

In the responsiveness analysis, the sensitivity was lower than the specificity; sensitivity could have been maximized by using lower CLASI scores, but this would have caused the specificity to decrease. For the purposes of a clinical trial, we felt that it was more important for the CLASI to be specific than sensitive. With high specificity, the degree of false-positive responses decreases, thereby minimizing the inclusion of patients that have not experienced a true clinical improvement.

In addition, the change in the CLASI score that indicates a clinical improvement was selected primarily based on the percentage of patients correctly classified rather than by optimizing sensitivity and specificity. This was done because the latter suggested a change in the CLASI activity score of merely one point, which is only 69% specific for improvement. As discussed above, we felt it was important to have high specificity and therefore based the analysis on percentage of patients correctly classified instead.

These applications are critical in clinical trials because they provide a standardized technique for quantifying and describing disease activity. Previously, investigators have relied on their own individualized, often subjective, methods for describing disease severity and response to treatment in CLE. As such, it can be difficult to know exactly what is meant when a patient is described as having “moderate disease” or as experiencing a “clinical improvement”. It is also difficult to directly compare the results of various trials when different methods are employed to determine efficacy of a particular drug. The CLASI addresses these issues by providing a simple, quantitative clinical tool that standardizes the way disease activity is described and provides guidelines for identifying a clinical change.

There are, however, some limitations to this study that should be addressed in the future. First, due to the small sample size, patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease were analyzed as one group. However, it is likely that the patient’s baseline CLASI score influences the magnitude of change seen in a clinical improvement; thus, a patient with mild disease may have a significant improvement even with a small change in the CLASI activity score (<4 points), whereas a patient with severe disease may require a larger change in the CLASI activity score to detect a significant improvement (>4 points). Follow-up studies should therefore be done in which patients are stratified according to disease severity, with separate analyses performed on each group.

Second, also due to the small sample size, patients with every type of CLE were analyzed as one group, including those with localized and generalized disease. The patients with localized disease, by definition, will always have relatively low CLASI scores, even if they have severe disease. It will therefore be more difficult for such patients to demonstrate the changes in CLASI scores that have been associated with a clinical improvement. In these cases, investigators may choose to look at the percent change in the CLASI activity score rather than signed change. Follow-up studies should include a separate analysis of patients with localized disease to determine how to define the severity groups and how to identify a clinical improvement using signed changes in the CLASI activity score.

This aim of this study was to evaluate responsiveness; the CLASI, however, has other practical applications, such as identifying flares, which will be examined in future studies.

Overall, this study provides the framework for using the CLASI to characterize disease severity and to identify a clinical improvement. While more studies must be done to address specific patient populations, this analysis provides a foundation for the practical use of the CLASI in clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding/Support: This material is based upon work supported by the National Institutes of Health, including NIH K24-AR 02207 (Werth) and training grant NIH T32-AR007465-25 (Klein). This work was also partially supported by a Merit Review Grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

Dr. Werth had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Werth and Klein.

Acquisition of data: Klein, Moghadam-Kia, Okawa, Werth. Analysis and interpretation of data:

Werth, Klein, Taylor, Troxel. Drafting of the manuscript: Klein. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Klein, Moghadam-Kia, LoMonico, Okawa, Coley, Taylor, Troxel, Werth. Statistical analysis: Taylor, Troxel, Coley. Obtained funding: Werth.

Study supervision: Werth.

Financial Disclosures: None reported. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Rachel Klein, Email: rachelu@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Siamak Moghadam-Kia, Email: siamakmk@gmail.com.

Jonathan LoMonico, Email: johnnyla99@gmail.com.

Joyce Okawa, Email: Joyce.Okawa@uphs.upenn.edu.

Chris Coley, Email: ccoley@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Lynne Taylor, Email: taylor2@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Andrea B. Troxel, Email: atroxel@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Victoria Werth, Email: werth@mail.med.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Nov;125(5):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krathen MS, Dunham J, Gaines E, et al. The Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity and Severity Index: expansion for rheumatology and dermatology. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Mar 15;59(3):338–344. doi: 10.1002/art.23319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonilla-Martinez ZL, Albrecht J, Troxel AB, et al. The cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index: a responsive instrument to measure activity and damage in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2008 Feb;144(2):173–180. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erceg A, Bovenschen HJ, van de Kerkhof PC, de Jong EM, Seyger MM. Efficacy and safety of pulsed dye laser treatment for cutaneous discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Apr;60(4):626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreuter A, Gaifullina R, Tigges C, Kirschke J, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: response to antimalarial treatment in 36 patients with emphasis on smoking. Arch Dermatol. 2009 Mar;145(3):244–248. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreuter A, Tomi NS, Weiner SM, Huger M, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Mycophenolate sodium for subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus resistant to standard therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Jun;156(6):1321–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbach MOJ, Krathen M, Braunstein I, Kovarik C, Werth VP. Clinical and histopathological analysis of subjects treated with lenalidomide for refractory chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (abstract) Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129:S22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Guidance for Industry. [Accessed March 2, 2010];Systemic Lupus Erythematosus- Developing Drugs for Treatment. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm072063.pdf.

- 9.Sontheimer RD. The lexicon of cutaneous lupus erythematosus--a review and personal perspective on the nomenclature and classification of the cutaneous manifestations of lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1997;6(2):84–95. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997 Nov;133(11):1433–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]