Abstract

Rationale

Epigenetic marks are crucial for organogenesis, but their role in heart development is poorly understood. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27, establishing H3K27me3 repressive epigenetic marks that promote tissue-specific differentiation by silencing ectopic gene programs.

Objective

We studied the function of PRC2 in murine heart development using a tissue-restricted conditional inactivation strategy.

Methods and Results

Inactivation of the PRC2 subunit Ezh2 by Nkx2-5Cre (Ezh2NK) caused lethal congenital heart malformations, namely compact myocardial hypoplasia, hypertrabeculation, and ventricular septal defect. Candidate and genome-wide RNA expression profiling and chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses of Ezh2NK heart identified genes directly repressed by EZH2. Among these were the potent cell cycle inhibitors Ink4a/b, whose upregulation was associated with decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation in Ezh2NK. EZH2-repressed genes were enriched for transcriptional regulators of non-cardiomyocyte expression programs, such as Pax6, Isl1, Six1. EZH2 was also required for proper spatiotemporal regulation of cardiac gene expression, as Hcn4, Mlc2a, and Bmp10 were inappropriately upregulated in ventricular RNA. PRC2 was also required later in heart development, as indicated by cardiomyocyte-restricted TNT-Cre inactivation of the PRC2 subunit Eed. However, Ezh2 inactivation by TNT-Cre did not cause an overt phenotype, likely due to functional redundancy with Ezh1. Thus early Ezh2 inactivation by Nk2-5Cre caused later disruption of cardiomyocyte gene expression and heart development.

Conclusions

Our study reveals a previously undescribed role of EZH2 in regulating heart formation and shows that perturbation of the epigenetic landscape early in cardiogenesis has sustained disruptive effects at later developmental stages.

Keywords: Heart development, epigenetics, transcriptional regulation

Congenital heart disease is among the most frequent major birth defects. Intensive studies have revealed numerous genes that control the intricate process of heart development in humans and mice1. Prominent among congenital heart disease genes are transcription factors, pointing to the important role of transcriptional regulation in orchestrating heart development2. Recent studies on the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex have also highlighted the important role of chromatin structure in regulating heart development3. In Drosophila, Polycomb group genes genetically antagonize these chromatin remodeling genes4. The Polycomb genes Enhancer of Zeste 2 (EZH2), Embryonic Ectoderm Development (EED), and Suppressor of Zeste 12 (SUZ12) are major components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2)5. This highly conserved complex trimethylates histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27), establishing the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark that characterizes transcriptionally repressed chromatin4. Through this mechanism, PRC2 regulates tissue-specific differentiation by orchestrating the repression of inappropriate tissue- and stage-specific transcriptional programs6-8. The role of histone methylation or PRC2 in heart development has not been reported.

Here, we used Cre-LoxP technology to conditionally inactivate Ezh2, the catalytic subunit of PRC25, 9, in the developing heart. Cardiac Ezh2-deficiency during a narrow window early in cardiogenesis caused abnormal cardiac gene expression and lethal heart malformations that included hypertrabeculation, thinning of the compact myocardium, and ventricular and atrial septal defects. Our results indicate that establishment of the epigenetic landscape early in cardiogenesis is necessary for normal heart development. Perturbation of this process may contribute to congenital heart disease.

Methods

Ezh2fl, Nkx2-5Lz, TNT-Cre, and Nkx2-5Cre alleles were described previously7, 10-12. Construction of the Eedfl allele will be described elsewhere. All animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Children’s Hospital Boston.

Histological sections were processed as described13 and imaged on an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. Antibodies are listed in Online Table I. For morphometric measurements, we measured transverse sections through the atrioventricular valves. Wall thickness was calculated as the ventricular compact myocardial thickness divided by its outer circumference. Trabecular and myocardial area were measured in Adobe Photoshop after selection of image areas with myocardial color range.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRTPCR) was performed with sybr green chemistry and normalized to Gapdh. ChIP was performed with antibodies listed in Online Table I. Primers for qRTPCR and quantitative ChIP-PCR (ChIP-qPCR) are provided in Online Table II.

Expression profiling by RNA-seq was performed as described, with omission of library normalization steps14. Reads mapping to each gene were analyzed for differential expression using exact tests between two negative binomial groups15, and the false discovery rate was calculated using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. ChIP-seq was performed as described16. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000. ChIP-seq peaks were identified using Sole-Search17 with default parameters. Genomic intervals were annotated, combined, and analyzed for gene ontology term enrichment using the completeMOTIFs pipeline18. Data were deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE29997.

qRTPCR results were expressed as mean ± SEM, while ChIP-qPCR results were displayed as mean ± SD. Two group comparisons were performed with Student’s t-test with P<0.05 taken as statistically significant.

Results

Early cardiac inactivation of Ezh2 by Nkx2-5Cre disrupts heart development

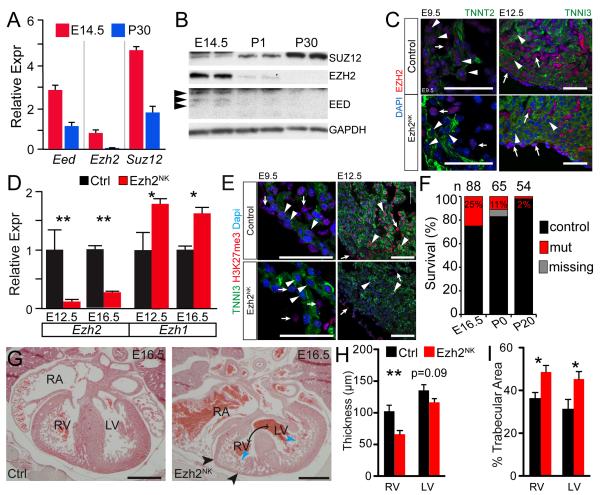

We investigated expression of PRC2 subunits Eed, Ezh2, and Suz12 in fetal and adult heart. In fetal heart, all three subunits were robustly expressed at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A-B). In adult heart, these transcripts were downregulated, and EZH2 and EED proteins were undetectable. Despite reduced Suz12 mRNA, SUZ12 protein was upregulated in adult heart (Fig. 1B), suggesting post-transcriptional regulation. Immunohistochemistry of E9.5 and E12.5 heart confirmed EZH2 expression in cardiomyocytes, as well as non-myocytes (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Cardiac inactivation of Ezh2 by Nkx2-5Cre.

A. Expression of PRC2 components in developing and postnatal heart by qRTPCR. E, embryonic day. P, postnatal day.

B. Cardiac expression of PRC2 proteins by western blotting. EED was present as three isoforms (arrowheads).

C. EZH2 expression in E9.5 and E12.5 heart, and loss of expression in Ezh2NK cardiomyocytes. Arrowheads indicate cardiomyocytes. Note lack of cardiomyocyte EZH2 in mutants. Arrows indicate non-myocytes, with unaltered EZH2 expression. Bar = 50 μm.

D. Inactivation of Ezh2 and compensatory upregulation of Ezh1, as measured by qRT-PCR, in Ezh2NK and control heart at E12.5 and E16.5. n=4.

E. Heart cryosections stained for PRC2 product H3K27me3 and cardiac marker TNNI3. H3K27me3 was reduced in Ezh2NK cardiomyocytes (arrowheads) but not non-myocytes (arrows) compared to control. Bar = 50 μm.

F. Survival of EZH2NK mice. Most mice died perinatally. Numbers above bars indicate sample size.

G. Cardiac abnormalities in Ezh2NK embryos. H&E stained transverse sections of E16.5 embryos revealed thinning of compact myocardium (black arrowheads), excessive myocardial trabeculation (blue arrowheads), right atrial dilation, and membranous and muscular VSDs (double headed arrows). Bar=500 μm.

H-I. Thinning of RV and LV compact myocardium and increased myocardial trabecular area. n=4 control and 7 mutant.

**, P < 0.01. *P<0.05

To study the role of PRC2 in heart development, we inactivated an Ezh2 floxed allele (Ezh2fl; ref. 7) in cardiomyocytes using Nkx2-5Cre 12. By E9.5, Ezh2fl/fl::Nkx2-5Cre/+ (abbreviated Ezh2NK) cardiomyocytes exhibited markedly reduced EZH2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 1C). EZH2 expression appeared unchanged in epicardial and endocardial cells, although we cannot exclude Ezh2 inactivation in a subset of these cells. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) confirmed marked Ezh2 depletion in Ezh2NK mutant hearts (Fig. 1D). Ezh1, which shows partial functional redundancy with Ezh27, was upregulated in Ezh2NK mutants (Fig. 1D). Increased Ezh1 expression may mitigate the severity of the Ezh2NK phenotype (Fig. 1D). The major described product of EZH2 methyltransferase activity, H3K27me3, was markedly reduced in Ezh2NK mutants at E9.5 and E16.5 (Fig. 1E), consistent with an essential role of EZH2 in H3K27 trimethylation.

Ezh2NK embryos were present at the expected Mendelian ratio at E16.5, but the vast majority died perinatally so that only 2% of pups at weaning had the mutant genotype (Fig. 1F). The mutant hearts had four chambers, four valves, and normal inflow and outflow tract alignment. The ventricular septa were abnormal and exhibited both muscular and membranous septal defects (Fig. 1G). The compact myocardium (free wall) of both ventricles was hypoplastic, with the right ventricle (RV) more severely affected than the left ventricle (LV). Trabeculation of both ventricles was increased. Morphometric measurements confirmed these observations (Fig. 1H-I). The right atria were markedly dilated, and some mutant hearts had atrial septal defects.

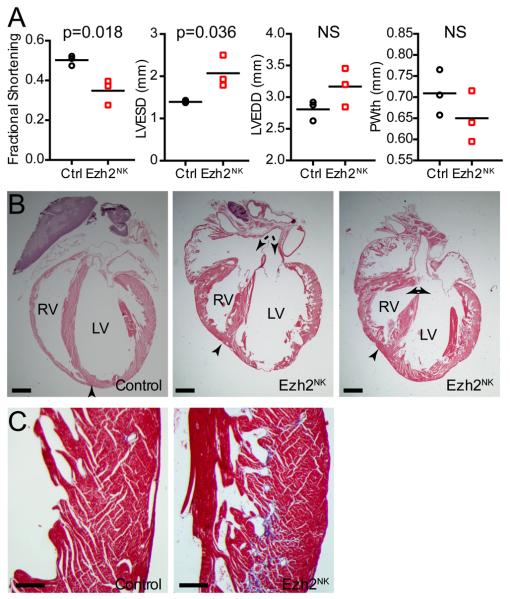

Rare Ezh2NK mutant mice survived to adulthood. These had persistent hypertrabeculation, RV hypoplasia, atrial and ventricular septal defects, myocardial fibrosis, and moderately impaired left ventricular systolic function (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Phenotype of Ezh2NK mutants that survive to adulthood.

A. Echocardiography at 8 wks of age showed that rare Ezh2NK survivors had diminished systolic heart function, measured by the fractional shortening. LVEDD, LV end diastolic diameter. LVESD, LV end systolic diameter. PWth, posterior wall thickness. n=3.

B. H&E stained histological sections demonstrated persistent ventricular hypertrabeculation. A subset of mutants had atrial and ventricular septal defect (dashed and solid double headed arrow, respectively). Arrowhead indicates tip of RV. Note that it does not reach the apex in mutants. Bar = 1 mm.

C. Trichrome stained sections revealed increased fibrosis in Ezh2NK mutants. Bar = 200 μm.

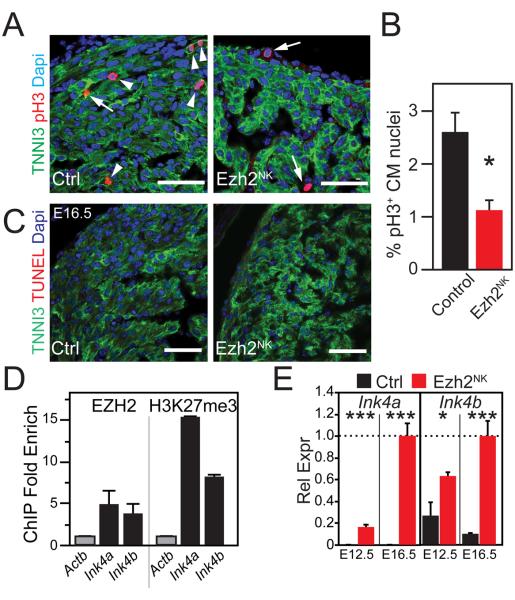

Decreased Cardiomyocyte Proliferation in Ezh2NK Mutant Heart

Hypoplasia of Ezh2NK compact myocardium suggested reduced cardiomyocyte proliferation. To test this hypothesis, we stained histological sections of E16.5 control and mutant heart for phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3), a cell cycle M phase marker (Fig. 3A). Loss of EZH2 caused more than two fold reduction in the fraction of pH3+ cardiomyocytes (P<0.05; Fig. 3A-B). In contrast, we did not detect significant cardiomyocyte apoptosis by TUNEL staining in control or mutant heart (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation in Ezh2NK.

A. E16.5 heart cryosections stained for TNNI3 and mitosis marker phosphohistone H3 (pH3). pH3 staining decreased in Ezh2NK cardiomyocytes (arrowheads). Arrows indicate pH3 stained non-myocytes.

B. Quantitation of pH3 staining showed substantial decrease in Ezh2NK. n=5.

C. TUNEL staining of E16.5 heart cryosections did not show a difference in apoptosis between control and Ezh2NK mutants.

D. EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-qPCR for Ink4a/Ink4b in E12.5 heart ventricle. Actb was a negative control. n=3.

E. Marked upregulation of cell cycle inhibitors Ink4a and Ink4b in Ezh2NK E12.5 and E16.5 ventricle. n=4.

*, P < 0.05. ***, P < 0.001. Bar = 50 μm.

In skin, cultured fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells, PRC2 directly repressed Ink4a and Ink4b (MGI: Cdkn2a/b), powerful negative cell cycle regulators that inhibit the G1-to-S transition19, 20. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR), we found that EZH2 and H3K27me3 were enriched at Ink4a and Ink4b promoters of E12.5 heart ventricle (Fig. 3D). Ink4a and Ink4b were dramatically upregulated in EZH2-deficient ventricle at both E12.5 and E16.5 (Fig. 3E). Thus, Ezh2 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation in fetal heart by repressing the negative cell cycle regulators Ink4a and Ink4b.

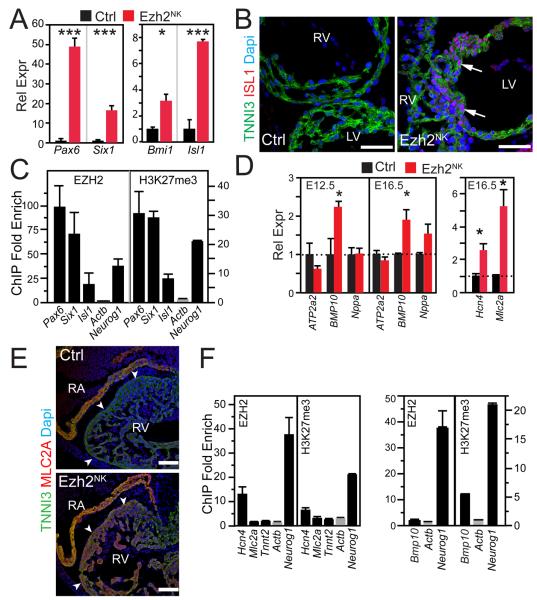

Abnormal Gene Expression in Ezh2NK Mutant Heart

PRC2 promotes lineage-specific differentiation by repressing inappropriate transcriptional programs. To investigate this function of EZH2 in heart, we measured the expression of selected master transcriptional regulators of non-cardiac programs by qRTPCR (Fig. 4A). Pax6, a transcriptional regulator of eye, brain, spinal cord, and pancreas development21, was upregulated 49-fold in Ezh2NK mutant heart. Six1, a homeodomain transcription factor expressed in key progenitor populations including second heart field and downregulated in most differentiated tissues including cardiomyocytes22, was upregulated 17-fold in Ezh2NK mutant heart. Isl1, an essential regulator of cardiac progenitor differentiation whose expression is normally downregulated in differentiated cardiomyocytes23, was upregulated 7.5-fold. We further confirmed upregulation of ISL1 protein in differentiated cardiomyocytes by immunostaining (Fig. 4B). Consistent with qRTPCR results, ISL1 immunoreactivity was present in E9.5 Ezh2NK ventricular cardiomyocytes but not in littermate control cardiomyocytes. Both EZH2 and H3K27me3 were highly enriched at Pax6, Six1, and Isl1 promoters by ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 4C), indicating that EZH2 directly represses these genes by establishing H3K27me3 repressive marks.

Figure 4. Abnormal gene expression in Ezh2NK heart ventricle.

A. Expression of key transcriptional regulators in Ezh2NK and control E12.5 ventricle as measured by qRTPCR. n=4.

B. Immunostaining of E9.5 mutant and control cryosections for ISL1. Mutant cardiomyocytes showed abnormal persistence of ISL1 immunoreactivity in ventricular cardiomyocytes (arrows).

C. EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-qPCR from E12.5 ventricle for transcriptional regulators upregulated in panel A. Actb and Neurog1 were negative and positive controls, respectively.

D. Expression of cardiac genes in mutant and control embryo ventricle. n=4.

E. MLC2A and TNNI3 immunohistochemistry in E12.5 Ezh2NK ventricle. Note ectopic MLC2A expression (red) in mutant ventricle (arrowheads). Bar = 100 μm.

F. EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-qPCR from E12.5 ventricle, for cardiac genes upregulated in panel D. Actb and Neurog1 were negative and positive controls, respectively. n=3.

*, P < 0.05. ***, P < 0.001. Bar = 50 μm.

Cardiac genes undergo an orderly change of expression during cardiomyocyte maturation. Bmp10, which promotes cardiomyocyte growth and ventricular trabeculation 24, 25, is expressed in compact and trabecular cardiomyocytes at E10.5, becomes restricted to trabecular cardiomyocytes by E12.5, and is not longer expressed in ventricles by E15.524, 25. In Ezh2NK mutant embryos, Bmp10 expression was upregulated by over two fold at both E12.5 and E16.5 (Fig. 4D).

During cardiac morphogenesis, ventricular cardiomyocytes undergo lineage restriction, repressing genes normally expressed in atrial or conduction system cardiomyocytes. We measured the expression of conduction system or atrium specific markers in E16.5 ventricular myocardium. Hcn4, encoding a cardiac pacemaker channel normally restricted to conduction system myocardium26, was upregulated 2.6-fold (Fig. 4D). The atrial-specific myosin light chain isoform Mlc2a (MGI: Myl7) 27 was upregulated 5.3-fold in ventricular myocardium (Fig. 4D). Consistent with qRTPCR results, MLC2A immunoreactivity was present in E12.5 Ezh2NK ventricles, but not in littermates control ventricles (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that EZH2 is required to establish normal patterns of gene expression in the developing heart.

EZH2 and H3K27me3 were moderately enriched at the Hcn4 promoter of wild-type ventricles (Fig. 4F). However, neither was enriched at Mlc2a or Bmp10 promoters (Fig. 4F). Thus EZH2 directly represses some markers of regionalized cardiac gene expression, while its regulation of other such markers was either indirect or occurred through a mechanism other than H3K27me3 deposition.

Genome wide identification of EZH2-repressed cardiac genes

To obtain a global view of EZH2-regulated gene expression in the heart, we measured gene expression and EZH2 and H3K27me3 chromatin occupancy in E12.5 ventricle apex by RNA-seq and ChIP-seq, respectively (Table 1). In the RNA-seq experiment, we obtained 32.2 and 31.5 million uniquely aligned 50 nucleotide paired end reads from Ezh2 heterozgous control (Ezh2fl/+::Nkx2-5Cre/+) and mutant (Ezh2fl/fl::Nkx2-5Cre/+) hearts, respectively. Expression levels in control and mutant samples were compared based on the density of reads mapping to each gene. 511 genes were differentially expressed (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 and fold change more than 50%), including the previously validated genes Ink4a, Six1, Isl1, Pax6, Myh6, Hcn4, and Mlc2a (Fig. 5A and Online Table III). These 511 genes were enriched for functional terms related to gland, appendage, ear, and muscle development (Online Table III).

Table 1.

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analysis of EZH2 Gene Regulation in E12.5 ventricle

| sample | Raw Reads |

Aligned Reads |

Read Type |

Peak Num |

Gene Num |

Shared Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ChIP-seq

| ||||||

| WT, EZH2 ChIP | 29745815 | 23069853 | 50-SE | 1362 | 819 | 697 |

| WT, H3K27me3 ChIP | 21638473 | 16969347 | 50-SE | 2132 | 1052 | 697 |

| Input chromatin | 27266069 | 21842887 | 50-SE | na | na | na |

|

| ||||||

|

RNA-seq

| ||||||

| Ezh2fl/+::Nkx2-5Cre/+ | 43979446 | 32223129 | 50-PE | |||

| Ezh2fl/fl:: Nkx2-5Cre/+ | 44951256 | 31524326 | 50-PE | |||

Peak Num: number of peaks called by Sole-search using default parameters for histone modifications. Gene Num: number of peaks that occur within 5000 bp of an annotated transcription start site. Shared Genes: Genes in common between Ezh2 and H3K27me3.

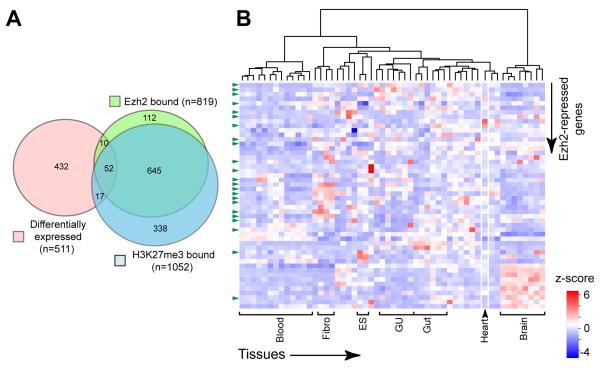

Figure 5. Genes directly repressed by EZH2 in E12.5 heart ventricle.

A. Analysis of differential gene expression (RNA-seq) and EZH2 and H3K27me3 chromatin occupancy (ChIP-seq). 52 genes were directly repressed by EZH2.

B. Heat map of 52 EZH2-repressed genes across multiple tissues. Multiple tissue expression atlas data were obtained from GSE15998. The full heat map is shown in Online Figure I. Most of these 52 genes showed low expression in heart and enhanced expression elsewhere, including brain, genitourinary (GU), gut, and blood tissues and fibroblast (fibro) and embryonic stem (ES) cells. Green arrowheads indicate transcriptional regulators.

To identify genes directly occupied by EZH2 and its H3K27me3 repressive mark, we performed ChIP-seq using wild-type E12.5 heart ventricle apex. We obtained 16-23 million uniquely aligned 50 nucleotide single end reads in input, EZH2, and H3K27me3 ChIP samples, leading to the identification of 819 and 1052 genes whose promoters were occupied by EZH2 and H3K27me3, respectively (Table 1 and Online Table IV). Consistent with EZH2 deposition of H3K27me3 epigenetic marks, in most (697) cases promoters were co-occupied by both marks (Fig. 5A). The ChIP-qPCR data from Figure 4 independently validated the ChIP-seq data: of the 7 ChIP-qPCR positive genes, 5 were recovered by ChIP-seq while two (Hcn4 and Ink4b) were not. EZH2 and H3K27me3 bound genes had functional annotations related to cell fate commitment, organ morphogenesis, and development of the limbs and skeletal, nervous, endocrine systems (Online Table IV).

Next, we looked for the genes that were likely to be directly and functionally regulated by EZH2 through deposition of H3K27me3. There were 52 genes that were both differentially expressed downstream of EZH2 loss of function and bound by H3K27me3 and EZH2. All 52 of these genes were upregulated in EZH2 loss of function (Fisher’s exact P < 0.0001), as expected for genes directly regulated by EZH2 through establishment of repressive H3K27me3 marks (Fig. 5A and Online Table V). These 52 EZH2-repressed genes were enriched 14-fold for transcriptional regulators (P = 3.9 × 10−9; green arrowheads Fig. 5B) and functional annotations related to gland, limb, forebrain, ear, and heart development (Online Table V). Among them were Ink4a, Six1, Isl1, and Pax6, identified by the candidate gene approach. The large majority of these showed reduced expression in heart compared to other tissues, such as brain (Fig. 5B; Online Figure I).

By analyzing correlations between gene expression in multiple tissues and conditions, in silico we identified tissue-specific gene expression modules and their transcriptional regulators (Cahan and Daley, manuscript in preparation). Components of 3 modules, one related to neuronal development and two related to fibroblast and mesenchymal-type cells, were overrepresented among genes upregulated in Ezh2NK (P < 0.01; Online Table VI). Key transcriptional regulators of these three modules were among the 52 EZH2-repressed genes (Online Table VI). These data support an essential role of EZH2 in repressing these mesenchymal and neuronal gene programs in cardiomyocytes.

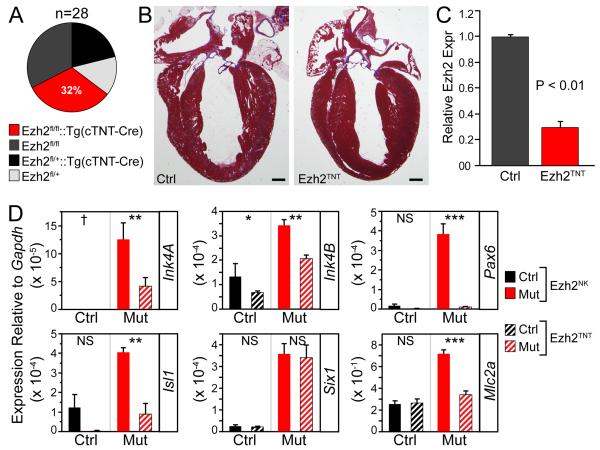

Later cardiac inactivation of Ezh2 by TNT-Cre is compatible with normal heart development

Gene inactivation by TNT-Cre occurs in differentiated cardiomyocytes slightly later than Nkx2-5Cre 11. Unlike Ezh2NK mutants, Ezh2fl/fl::Tg(TNT-Cre) mutant mice (Ezh2TNT) were born at the expected Mendelian frequency (Fig. 6A) and had normal heart structure. (Fig. 6B). Echocardiographic analysis showed no difference in heart function (control FS 50.5 ± 2.3% versus Ezh2TNT FS 50.7 ± 0.9%, n=7). qRTPCR validated efficient Ezh2 inactivation by E9.5 (Fig. 6C). The Nkx2-5Cre knockin allele is Nkx2-5 haploinsufficient. To exclude Nkx2-5 haploinsufficiency as the cause for the differences observed between Ezh2NK and Ezh2TNT mutants, we generated Ezh2fl/fl::Tg(TNT-cre)::Nkx2-5Lz/+ mice. Survival of these mice to weaning was not distinguishable from Ezh2TNT mice, indicating that Nkx2-5 haploinsufficiency did not account for the different phenotypes obtained using Nkx2-5Cre versus TNT-Cre.

Figure 6. Ezh2 inactivation by TNTCre was compatible with normal survival and normal heart development.

A. Survival of progeny from Ezh2fl/+::Tg(TNT-Cre) x Ezh2fl/fl matings.

B. Normal histology of Ezh2TNT heart at 8 weeks of age. Masson’s trichrome stained paraffin sections. Bar = 500 μm.

C. TNT-Cre inactivation of Ezh2 at E9.5, measured by qRTPCR.

D. Gene expression in Ezh2NK compared to Ezh2TNT E12.5 heart ventricle, expressed as a ratio to the internal control gene Gapdh. Statistical comparisons were between Ezh2NK and Ezh2TNT mutant embryos, and between corresponding littermate controls. NS, not significant. *, P<0.05. **, P<0.01. ***, P<0.001. †, not detectable.

Although by E9.5 the extent of EZH2 inactivation was similar between Ezh2NK and Ezh2TNT, Ezh2NK mutants developed lethal heart defects, while Ezh2TNT mutants did not. We compared the effect of Ezh2 inactivation by Nkx2-5Cre versus TNTCre on gene expression in E12.5 ventricle (Fig. 6D). The cell cycle inhibitors Ink4a and Ink4b were weakly upregulated in Ezh2TNT, but the degree of upregulation was substantially and significantly greater in Ezh2NK. The cardiac progenitor gene Isl1 and the non-cardiac transcriptional regulator Pax6 were also more strongly upregulated in Ezh2NK compared to Ezh2TNT. The gene Mlc2a, normally expressed in atrial myocardium, was upregulated in Ezh2NK but not Ezh2TNT ventricular RNA. However, the cardiac progenitor gene Six1 was upregulated to the same degree in Ezh2NK and Ezh2TNT, suggesting that Six1 upregulation by itself did not cause lethal heart malformation in combination with Ezh2 inactivation. Collectively these data indicate that slightly earlier inactivation of Ezh2 by Nkx2-5Cre compared to TNTCre causes sustained effects on gene expression and heart development.

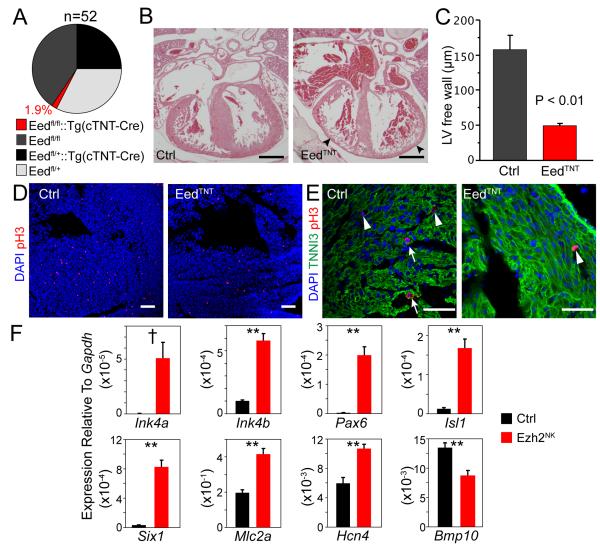

Ezh2 and the related Ezh1 show partial functional redundancy in some cell types7, 28. Functional redundancy between Ezh2 and Ezh1 in the fetal heart may account for the lack of phenotype in Ezh2TNT mutants. To test this hypothesis, we inactivated the essential, non-redundant PRC2 component Eed with TNT-Cre in fetal cardiomyocytes. In crosses between Eedfl/+:: Tg(TNT-Cre) and Eedfl/fl parents, at birth only 11% of progeny had the Eedfl/fl::Tg(TNT-Cre) mutant genotype (abbreviated EedTNT), and most mutants died by postnatal day 3, so that only 2% survived to weaning (Fig. 7A). These data indicated that EedTNT mutants had perinatal lethal heart defects. Histological sections of late gestation embryo hearts showed that the mutant compact myocardium was dramatically thinned (Fig. 7B). By morphometric analysis, the mutant compact myocardium thickness was reduced to 32% that of control myocardium (P<0.005, n=4; Fig. 7C). Unlike Ezh2NK mutants, EedTNT mutants had intact atrial and ventricular septae. Consistent with myocardial thinning, cardiomyocyte proliferation, as assessed by pH3 staining, was strongly reduced (Fig 7D-E). As in Ezh2NK, EedTNT mutants exhibited strong upregulation of Ink4a, Ink4b, Isl1, Pax6, and Six1 (Fig. 7F). Cardiac genes Mlc2a and Hcn4 also were upregulated in EedTNT, also as in Ezh2NK. However, Bmp10 was downregulated in EedTNT, whereas it was upregulated in Ezh2NK. These data indicate an ongoing requirement for PRC2 in fetal cardiomyocytes for normal heart growth. This requirement was not reflected in Ezh2TNT mutants, likely due to functional redundancy with Ezh1.

Figure 7. Eed inactivation by TNTCre caused lethal heart defects.

A. Survival of progeny from Eedfl/+::Tg(TNT-Cre) x Eedfl/fl matings.

B. H&E stained paraffin sections of E16.5 EedTNT and control embryos. Eed inactivation dramatically reduced compact myocardium thickness (arrowheads).

C. Morphometric analysis of compact myocardial thickness. n=4.

D-E. pH3 staining of EedTNT and control myocardium. D, low power overview showing reduced pH3 staining in mutants. Bar = 100 μm. E. High power magnification with co-staining for cardiomyocyte marker TNNI3. pH3+ cardiomyocyte (arrows) frequency was reduced in mutants. Arrowheads indicate pH3+ non-myocytes. Bar = 50 μm.

F. Gene expression abnormalities in E12.5 EedTNT mutant ventricle compared to control. **, P<0.01. †, expression undetectable in control.

Discussion

Organ formation requires establishing and maintaining tissue-specific gene expression programs in response to developmental cues. This involves both activation of tissue-specific genes and repression of inappropriate genes. By repressing inappropriate gene expression, polycomb group genes play pivotal roles in cellular differentiation and organ formation. Our results establish the essential role of PRC2 and its subunits EZH2 and EED in orchestrating heart development and cardiac gene expression. Loss of EZH2 in cardiac progenitors and in cardiomyocytes mediated by Nkx2-5Cre resulted in lethal heart abnormalities and disrupted cardiomyocyte gene expression. The ongoing requirement for PRC2 activity in cardiomyocytes was reinforced by TNT-Cre-mediated EED loss of function. Thus our studies of PRC2 function in the developing heart highlight the key role of histone modifications and the chromatin landscape in regulating cardiac gene expression and heart development.

We identified 52 genes that were directly repressed by EZH2-mediated deposition of H3K27me3. These were highly enriched for transcriptional regulators of non-cardiomyocyte gene expression programs, particularly those of neuronal and mesenchymal cells. Expression of these ectopic programs likely contributed to abnormal heart development and function in Ezh2NK.

Interestingly, only a small fraction of genes occupied by EZH2 and H3K27me3 were upregulated by Ezh2 inactivation (52 out of 697). This observation may be partially explained functional redundancy with Ezh1, which showed compensatory upregulation. However, overall H3K27me3 levels were strongly reduced in the Ezh2NK mutant. This suggests that additional mechanisms besides PRC2-mediated deposition of H3K27me3 maintain repression of the majority of Ezh2/H3K27me3 repressed genes. These additional mechanisms may include establishment of other epigenetic repressive marks, such as DNA methylation29. EZH2 and H3K27me3 may participate in initiation of these additional repressive marks, but may be dispensible for their maintenance.

One of the major effects of PRC2 loss of function (Ezh2NK and EedTNT) was dramatic thinning of the compact myocardium and decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation. PRC2 inactivation derepressed the potent cell cycle inhibitors Ink4a/b. The strength of Ink4a/b upregulation correlated with myocardial hypoplasia, with Ezh2NK and EedTNT mutants exhibiting strong upregulation, and Ezh2TNT mutants showing less substantial upregulation. PRC2 has been shown to repress Ink4a/b and promote cellular proliferation in skin maturation, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells19, 20, suggesting that this is a common mechanism by which PRC2 regulates proliferation in development and disease.

The normal spatiotemporal regulation of cardiac gene expression was also disrupted in Ezh2NK mutants. Mlc2a and Hcn4, genes normally confined to the atria and conduction system, respectively 26, 27, were inappropriately expressed in the mutant ventricle. We also detected upregulation of a third cardiac gene, Bmp10, a secreted regulator of myocardial growth and trabeculation, in Ezh2NK mutant heart. Mlc2a upregulation was also observed in EedTNT mutant heart, suggesting that PRC2 acts genetically upstream of this gene to repress its ventricular expression. On the other hand, Bmp10 was downregulated in EedTNT, suggesting that its regulation by PRC2 is complex. In addition, expression of Bmp10 did not track with myocardial growth phenotypes, as it was also upregulated in Ezh2TNT (phenotypically normal) and downregulated in EedTNT (phenotypically similar to Ezh2NK). Thus the pathogenic role of Bmp10 upregulation in Ezh2NK is uncertain.

PRC2 represses gene expression by establishing H3K27me3 epigenetic marks. EZH2 and H3K27me3 were highly enriched at wild-type Ink4a and Ink4b, consistent with an important role for PRC2 in repressing these cell cycle genes. Hcn4 was moderately enriched for H3K27me3 and EZH2 in wild-type ventricle, suggesting that its regulation by EZH2 is also direct. Mlc2a and Bmp10, however, were not substantially enriched for either H3K27me3 or EZH2, suggesting that their regulation by EZH2 was through a mechanism other than direct EZH2 occupancy and H3K27me3 deposition. In fact, the large majority (432/511) of genes differentially expressed in EZH2 mutants were not occupied by either EZH2 or H3K27me3, suggesting that either secondary effects lead to their differential expression, or that PRC2 regulates them through additional non-canoncial mechanisms.

H3K27me3 epigenetic marks serve as docking sites for repressive complexes including the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1). The PRC1 complex component Polyhomeotic-like 1 (aka Rae28) was shown to be essential for heart development, in part by sustaining expression of the Nkx2-5 30. More recently, sumoylation of another PRC1 component, Pc2, was shown to enhance PRC1 recruitment to H3K27me3, and excessive Pc2 sumoylation caused by inactivation of Senp2, encoding a de-sumoylating enzyme, was linked to abnormal cardiac development and reduced cardiomyocyte proliferation 31. Indeed, heterozygous loss of SUMO-1 caused perinatal lethality and cardiac septal defects, and SUMO-1 was required for normal expression of cell cycle genes in the fetal heart 32. The interplay between sumoylation and polycomb-mediated gene silencing may be complex, as both EZH2 and SUZ12 have been shown to be sumoylated 33. The regulation and biological significance of these modifications remain unknown.

While Ezh2 inactivation by Nkx2-5Cre caused lethal congenital heart malformations, unexpectedly its inactivation by TNT-Cre did not. These two Cre alleles differ in several ways: (a) timing, with Nkx2-5Cre being active in cardiac progenitors and TNT-Cre restricted to differentiated cardiomyocytes; (b) Nkx2-5 gene dosage, due to haploinsufficiency in Nkx2-5Cre; and (c) recombination domain, with TNT-Cre constrained to differentiated cardiomyocytes and Nkx2-5Cre potentially additionally including pharyngeal endoderm, endocardium, and epicardium 12, 34. Nkx2-5 haploinsufficiency did not unmask a phenotype in Ezh2TNT::Nkx2-5Lz/+ heart, excluding this possibility. Nkx2-5Cre activity in pharyngeal endoderm was not central to causing the Ezh2NK phenotype, since Ezh2NK hearts had normal outflow tracts and their abnormalities primarily resided in the ventricles. By immunohistochemistry, EZH2 persisted in the majority of non-myocytes in the Ezh2NK ventricle, although it may have been inactivated in a minor subset of non-myocytes. This observation suggests that Ezh2 inactivation by Nkx2-5Cre and TNTCre occurred in similar spatial domains, and thus differences in spatial recombination domains are unlikely to account for the dramatic difference in phenotype between Ezh2NK and Ezh2TNT. Conditional inactivation of the non-redundant PRC2 component Eed by TNTCre indicates that PRC2 is required in the TNTCre recombination domain, providing further strong support for this this conclusion (see below). Ezh1 has been shown to functionally substitute for Ezh2 in postnatal skin homeostasis28 and in execution of embryonic stem cell pluripotency7. Collectively, these data suggest that Ezh1 and Ezh2 are functionally redundant in cardiomyocytes but not in cardiac progenitor cells (see summary model, Online Figure II). As a result, there is a small window during which Ezh2 is indispensible in cardiac progenitor cells, and this window is probed by Nkx2-5Cre but not TNT-Cre.

TNTCre inactivation of EED recapitulated many aspects of the phenotype observed with Nkx2-5Cre inactivation of EZH2, including thin compact myocardium and hypertrabeculation. However, EedTNT mutants had intact cardiac septae, while EZH2NK had both atrial and ventricular septal defects. We believe this difference is due to the timing of cardiomyocyte inactivation by Nkx2-5Cre compared to TNTCre. First, the majority of non-myocytes did not undergo Ezh2 inactivation in Ezh2NK mutants. Second, Eed inactivation with Nkx2-5Cre did fully recapitulate the EZH2NK phenotype, including septal defects (He and Pu, unpublished data), strongly arguing that both proteins contribute to cardiac septation through the PRC2 complex. Third, inactivation of Eed in endocardium by Tie2Cre did not cause defects in the muscular septae or in myocardial growth (Zhang and Pu, unpublished data). The membranous ventricular septum also constricts normally in these embryos. However, fetal death due to hematological defects before the time that closure of the membranous septum is normally completed prevented us from fully excluding a role of endocardial PRC2 in formation of the membranous ventricular septum. Together the data strongly support the model that earlier PRC2 inactivation in cardiomyocytes by Nkx2-5Cre compared to TNTCre causes septal defects during later heart development.

Interestingly, abnormalities in gene expression and chromatin landscape initiated in cardiac progenitor cells as a result of EZH2 loss of function were sustained in cardiomyocytes, despite the fact that EZH2 was no longer essential in cardiomyocytes. Later inactivation of EZH2 by TNTCre either did not change the expression of these genes, or changed them to a lesser degree. This observation likely reflects a form of “epigenetic memory”, in which features of the chromatin landscape established under the direction of transient developmental cues are maintained in the absence of those cues. For PRC2-established H3K27me3 marks, this appears to be implemented at a molecular level by mechanisms that recruit PRC2 to pre-existing H3K27me3 marks, leading to maintenance of these marks and their propagation after cell division35, 36. Thus, transient loss of PRC2 activity in Ezh2NK mutant cells would disrupt maintenance of existing H3K27me3 marks and establishment of new marks. Partial restoration of PRC2 activity as a result of Ezh1 expression would then be incapable of re-establishing the proper H3K27me3 modifications. This may account for the severe global decrease of H3K27me3 and abnormalities of gene expression in E12.5 Ezh2NK cardiomyocytes, at a stage when the Ezh2TNT mutants indicate there is sufficient PRC2 activity to sustain normal heart development (see Online Figure II). Thus our results show that transient insults to the chromatin landscape early in embryo development can have delayed and sustained effects on cardiac morphogenesis and gene regulation. This result has strong implications for understanding the pathogenesis of congenital heart disease, and may provide new insights into how transient environmental exposures can disrupt organogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is known?

Development of the heart requires tightly choreographed changes in gene transcription.

Epigenetic histone modifications are essential regulators of gene transcription.

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) catalyzes trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a major epigenetic repressive mark.

What new information does this article contribute?

PRC2 is essential for normal heart development.

PRC2 represses non-cardiac transcriptional programs and contributes to normal spatiotemporal regulation of cardiac gene expression.

Perturbation of the epigenetic landscape early in cardiac morphogenesis has sustained disruptive effects at later developmental stages.

Congenital heart disease is one of the most frequent birth defects, and transcription factors are prominent among congenital heart disease genes. Covalent modification of histones is being increasingly recognized as a critical transcriptional regulatory mechanism, but little is known about the role of covalent histone modifications in heart development. In this article, we report on cardiac inactivation of two essential subunits of PRC2, the only enzyme known to establish repressive H3K27me3 marks. Our study shows that PRC2 is required for normal heart development. PRC2 was required to repress non-cardiac transcriptional programs, as well as potent cell cycle inhibitors and spatiotemporally regulated cardiac genes. Early Nkx2-5Cre-mediated inactivation of EZH2, the PRC2 catalytic subunit, caused perinatal lethal heart malformations. Interestingly, later TNT-Cre-mediated inactivation of EZH2 was compatible with normal survival. This was likely due to functional redundancy with EZH1, as TNT-cre-mediated inactivation of the non-redundant PRC2 subunit Eed also caused lethal heart malformations. Thus our results demonstrate an essential role for PRC2 and epigenetic transcriptional regulation in heart development. Our data suggest that perturbation of the epigenetic landscape early in cardiogenesis has sustained, disruptive effects at later stages. These results provide new insights into the transcriptional regulation of heart development and the pathogenesis of congenital heart disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding This work was supported by funding from the NIH (WTP, U01HL098166 and R01HL095712) and the American Heart Association (AH, postdoctoral fellowship 10POST4290028), and by charitable donations from Edward Marram, Karen Carpenter, and Gail Federici Smith.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- qRTPCR

quantitative RTPCR

- ChIP-qPCR

quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ChIP-seq

chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next generation sequencing.

- RNA-seq

RNA analysis by next generation sequencing.

- Ezh2NK

mutant Ezh2fl/fl::Nkx2-5Cre/+ genotype

- Ezh2TNT

mutant Ezh2fl/fl::Tg(TNT-Cre) genotype

- EedTNT

mutant Eed::Tg(TNT-Cre) genotype

- pH3

histone H3 phosphorylated on serine 10, a marker of M phase of the cell cycle

- H3K27me3

histone H3 trimethylated on lysine 27

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this work to disclose.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Srivastava D. Making or breaking the heart: from lineage determination to morphogenesis. Cell. 2006;126:1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451:943–948. doi: 10.1038/nature06801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han P, Hang CT, Yang J, Chang CP. Chromatin remodeling in cardiovascular development and physiology. Circ Res. 2011;108:378–396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuettengruber B, Chourrout D, Vervoort M, Leblanc B, Cavalli G. Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell. 2007;128:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2893–2905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Hansen JB, Capillo M, Helin K. The polycomb group protein Suz12 is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3769–3779. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01432-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen X, Liu Y, Hsu YJ, Fujiwara Y, Kim J, Mao X, Yuan GC, Orkin SH. EZH1 mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Mol Cell. 2008;32:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, Bell GW, Otte AP, Vidal M, Gifford DK, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka M, Chen Z, Bartunkova S, Yamasaki N, Izumo S. The cardiac homeobox gene Csx/Nkx2.5 lies genetically upstream of multiple genes essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1269–1280. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao K, Langworthy M, Batts L, Brown CB, Moses HL, Baldwin HS. Tgfbeta signaling is required for atrioventricular cushion mesenchyme remodeling during in vivo cardiac development. Development. 2006;133:4585–4593. doi: 10.1242/dev.02597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an Nkx2-5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou B, Ma Q, Kong SW, Hu Y, Campbell PH, McGowan FX, Ackerman KG, Wu B, Zhou B, Tevosian SG, Pu WT. Fog2 is critical for cardiac function and maintenance of coronary vasculature in the adult mouse heart. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1462–1476. doi: 10.1172/JCI38723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christodoulou DC, Gorham JM, Herman DS, Seidman JG. Construction of normalized RNA-seq libraries for next-generation sequencing using the crab duplex-specific nuclease. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0412s94. Chapter 4:Unit4.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson MD, Smyth GK. Small-sample estimation of negative binomial dispersion, with applications to SAGE data. Biostatistics. 2008;9:321–332. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He A, Kong SW, Ma Q, Pu WT. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5632–5637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blahnik KR, Dou L, O’Geen H, McPhillips T, Xu X, Cao AR, Iyengar S, Nicolet CM, Ludascher B, Korf I, Farnham PJ. Sole-Search: an integrated analysis program for peak detection and functional annotation using ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuttippurathu L, Hsing M, Liu Y, Schmidt B, Maskell DL, Lee K, He A, Pu WT, Kong SW. CompleteMOTIFs: DNA motif discovery platform for transcription factor binding experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bracken AP, Kleine-Kohlbrecher D, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Gargiulo G, Beekman C, Theilgaard-Monch K, Minucci S, Porse BT, Marine JC, Hansen KH, Helin K. The Polycomb group proteins bind throughout the INK4A-ARF locus and are disassociated in senescent cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:525–530. doi: 10.1101/gad.415507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezhkova E, Pasolli HA, Parker JS, Stokes N, Su IH, Hannon G, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Ezh2 orchestrates gene expression for the stepwise differentiation of tissue-specific stem cells. Cell. 2009;136:1122–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozmik Z. Pax genes in eye development and evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo C, Sun Y, Zhou B, Adam RM, Li X, Pu WT, Morrow BE, Moon A, Li X. A Tbx1-Six1/Eya1-Fgf8 genetic pathway controls mammalian cardiovascular and craniofacial morphogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1585–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI44630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pashmforoush M, Lu JT, Chen H, Amand TS, Kondo R, Pradervand S, Evans SM, Clark B, Feramisco JR, Giles W, Ho SY, Benson DW, Silberbach M, Shou W, Chien KR. Nkx2-5 pathways and congenital heart disease; loss of ventricular myocyte lineage specification leads to progressive cardiomyopathy and complete heart block. Cell. 2004;117:373–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Shi S, Acosta L, Li W, Lu J, Bao S, Chen Z, Yang Z, Schneider MD, Chien KR, Conway SJ, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, Franco D, Shou W. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development. 2004;131:2219–2231. doi: 10.1242/dev.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marionneau C, Couette B, Liu J, Li H, Mangoni ME, Nargeot J, Lei M, Escande D, Demolombe S. Specific pattern of ionic channel gene expression associated with pacemaker activity in the mouse heart. J Physiol. 2005;562:223–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.074047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zammit PS, Kelly RG, Franco D, Brown N, Moorman AF, Buckingham ME. Suppression of atrial myosin gene expression occurs independently in the left and right ventricles of the developing mouse heart. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:75–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200001)217:1<75::AID-DVDY7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezhkova E, Lien WH, Stokes N, Pasolli HA, Silva JM, Fuchs E. EZH1 and EZH2 cogovern histone H3K27 trimethylation and are essential for hair follicle homeostasis and wound repair. Genes Dev. 2011;25:485–498. doi: 10.1101/gad.2019811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vire E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, Morey L, Van Eynde A, Bernard D, Vanderwinden JM, Bollen M, Esteller M, Di Croce L, de Launoit Y, Fuks F. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439:871–874. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirai M, Osugi T, Koga H, Kaji Y, Takimoto E, Komuro I, Hara J, Miwa T, Yamauchi-Takihara K, Takihara Y. The Polycomb-group gene Rae28 sustains Nkx2.5/Csx expression and is essential for cardiac morphogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:177–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang X, Qi Y, Zuo Y, Wang Q, Zou Y, Schwartz RJ, Cheng J, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for suppression of polycomb group protein-mediated gene silencing during embryonic development. Mol Cell. 2010;38:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Chen L, Wen S, Zhu H, Yu W, Moskowitz IP, Shaw GM, Finnell RH, Schwartz RJ. Defective sumoylation pathway directs congenital heart disease. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:468–476. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riising EM, Boggio R, Chiocca S, Helin K, Pasini D. The polycomb repressive complex 2 is a potential target of SUMO modifications. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Q, Zhou B, Pu WT. Reassessment of Isl1 and Nkx2-5 cardiac fate maps using a Gata4-based reporter of Cre activity. Dev Biol. 2008;323:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen KH, Bracken AP, Pasini D, Dietrich N, Gehani SS, Monrad A, Rappsilber J, Lerdrup M, Helin K. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1291–1300. doi: 10.1038/ncb1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, Sharpe ML, Son J, Drury W, Jr, Voigt P, Martin SR, Taylor WR, De Marco V, Pirrotta V, Reinberg D, Gamblin SJ. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature. 2009;461:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nature08398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.