Abstract

For tissue engineering applications, scaffolds should be porous to enable rapid nutrient and oxygen transfer while providing a three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment for the encapsulated cells. This dual characteristic can be achieved by fabrication of porous hydrogels that contain encapsulated cells. In this work, we developed a simple method that allows cell encapsulation and pore generation inside alginate hydrogels simultaneously. Gelatin beads of 150–300 μm diameter were used as a sacrificial porogen for generating pores within cell-laden hydrogels. Gelation of gelatin at low temperature (4 °C) was used to form beads without chemical crosslinking and their subsequent dissolution after cell encapsulation led to generation of pores within cell-laden hydrogels. The pore size and porosity of the scaffolds were controlled by the gelatin bead size and their volume ratio, respectively. Fabricated hydrogels were characterized for their internal microarchitecture, mechanical properties and permeability. Hydrogels exhibited a high degree of porosity with increasing gelatin bead content in contrast to nonporous alginate hydrogel. Furthermore, permeability increased by two to three orders while compressive modulus decreased with increasing porosity of the scaffolds. Application of these scaffolds for tissue engineering was tested by encapsulation of hepatocarcinoma cell line (HepG2). All the scaffolds showed similar cell viability; however, cell proliferation was enhanced under porous conditions. Furthermore, porous alginate hydrogels resulted in formation of larger spheroids and higher albumin secretion compared to nonporous conditions. These data suggest that porous alginate hydrogels may have provided a better environment for cell proliferation and albumin production. This may be due to the enhanced mass transfer of nutrients, oxygen and waste removal, which is potentially beneficial for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications.

Introduction

In tissue engineering, hydrogels have received much attention due to their hydrophilicity and structural similarity to the extracellular matrix (ECM). As a minimum requirement for ECM mimicking, hydrogels for tissue engineering should provide three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment and effective solute transport in and out of the scaffold as well as biocompatibility and biodegradability [1–4]. Effective mass transfer can be achieved by generating porous structure in the scaffolds or selecting highly permeable scaffold materials. Until now, various fabrication methods have been developed to generate pores in 3D tissue engineering scaffolds. To mention a few, salt leaching [5, 6], phase separation [7], freeze drying [8], photolithography [9–11] and 3D stereolithographic printing [4, 12, 13] were adopted for pore formation in the scaffolds. In these methods, cells were often seeded after pore generation onto the scaffolds, limiting their homogeneous distribution and cell in-growth throughout the scaffolds [14]. Inhomogeneous cell distribution may result in different cell coverage on the scaffolds and can cause non-uniform degradation of scaffold materials. To solve this problem, effective cell seeding strategies such as continuous circulation of cell suspension [15] and cell-encapsulated hydrogel scaffolds [14] were developed. Cell encapsulation in hydrogels showed significant achievements for tissue generation using promising techniques such as bioprinting [16], self-assembly [17], photolithographic [11] and laser-assisted photosensitive techniques [13]. However, few methods have been introduced with conventional porogen-based tissue engineering for fabricating porous hydrogels containing encapsulated cells. Indeed, encapsulation of cells inside hydrogels still remains an attractive approach and provides homogeneous cell distribution as well as 3D microenvironment for cultured cells [18]. Though general methods such as photocrosslinking used for cell-laden hydrogels provide 3D environment, they need enough pore space for cell migration, cell–cell interaction, in-growth and mass transfer supporting cell viability and cellular function over prolonged culture periods [19]. Thus, the ability to create 3D porous cell-laden hydrogels may be critical for hydrogel-based tissue engineering applications. To achieve in situ pore formation in the presence of encapsulated cells, chemical and physical process parameters for pore generation should be selected for maintaining cell viability and desired physical and biological functionality. In this paper, we report a simple method for fabrication of porous cell-laden alginate hydrogels with high mass transfer rate, homogeneous cell distribution and 3D microenvironment for enhanced cell functionality.

Here, alginate was selected as a base hydrogel material for 3D encapsulation of HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells. Alginate is a natural polysaccharide and forms a reversible crosslinking in the presence of calcium ions. It has been used as a matrix hydrogel material for various cell types such as chondrocytes, osteoblasts, embryonic stem cells and liver cells [1, 14, 20–22]. Dvir-Ginzberg et al have recently suggested that non-adhesive nature along with a macroporous structure of alginate is conducive for compacted spheroid formation leading to close cell–cell interaction and prolonged hepatocellular function [23]. To enhance mass transfer, we developed a gelatin-based in situ pore formation method compatible with cells. Gelatin, a fragmented protein from extracellular collagen molecules, shows thermogelling behavior. It gels at low temperature and dissolves in an aqueous solution at physiological temperature [24, 25]. Based on this property, Golden et al have used micromolded gelatin as a sacrificial component to create interconnected microchannels inside hydrogels using microfluidic molds [25]. This method enabled delivery of macromolecules and particles into the hydrogel channels.

In this study, we used a similar approach to generate pores in cell-laden alginate hydrogels by using gelatin beads as sacrificial porogen [22]. Gelatin microbeads were incorporated with the alginate solution containing cells and crosslinked alginate hydrogels were fabricated using calcium ions. The hypothesis of the work was that the dissolution of gelatin beads at physiological temperature will produce porous structure without deleterious effects on the encapsulated cells and will enhance mass transfer and cell function in vitro. HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells were chosen to investigate the effect of mass transfer on cell viability, proliferation and functionality such as albumin production.

Experimental

Gelatin bead preparation

Gelatin type A from porcine skin with 300 Bloom (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used as pore-generating material. Gelatin beads were fabricated via the water in oil (W/O) emulsification method modified from a previous report [26]. In brief, 10% (w/v) gelatin solution was prepared by dissolving gelatin in Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS, GibcoBRL, Rockville, MD) at 37 °C and autoclaved. A total of 5 mL of gelatin solution was added to the oil bath at a constant flow rate of 1 mL min−1 using a syringe pump containing 25 mL mineral oil with 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20 (Sigma) and stirred at 600 rpm. After gelatin addition, the oil–gelatin solution mixture was stirred for another 10 min and cooled over an ice bath for 10 min to induce gelatin gelling. The resulting gelatin beads–oil mixture was moved to a conical tube containing 4 °C Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS, GibcoBRL), centrifuged at 700 rpm for 5 min and supernatant oil was aspirated. Gelatin microspheres were selected with 150–300 μm sieves. Traces of mineral oil were rinsed with cold HBSS, centrifuged and removed by aspiration of supernatants three times. Gelatin microspheres were re-suspended in HBSS and stored in refrigerator until further use.

Fabrication of cell-laden porous hydrogel

All the solutions and molds used were ice cooled prior to alginate gelling. The alginate solution was prepared by dissolving 2 g sodium alginate (Sigma) in 100 mL DPBS, filtered with 0.22 μm nylon membrane syringe filter. Gelatin beads were mixed with the alginate solution in different volume ratios (0, 30, 50 and 80%) of final volume at 4 °C. To achieve this, gelatin beads were centrifuged and HBSS was removed. The required volume of the resulting beads was added into the cold alginate solution using 1 mL syringe at various volume ratios. Alginate–gelatin mixtures were then mixed with cell suspension. Cell-containing alginate–gelatin mixtures were then placed in disk-shaped agarose molds (D = 10 mm, h = 2 mm). To prepare agarose molds, agarose powder (Sigma) was dissolved in 2% (w/v) CaCl2 solution, gelled in 2 mm height mold and punctured with 10 mm diameter punches. For alginate hydrogel fabrication, the punched agarose mold was placed on top of a layer of the unpunched agarose sheet. The punched spaces in the agarose mold were then filled with the alginate solution mixed with gelatin beads and cells. Another layer of agarose sheet was added on top of alginate-filled agarose molds (figure 1). Alginate in the mold was crosslinked by calcium ions diffused from the agarose molds at room temperature. After gelling, alginate hydrogels with different gelatin contents were obtained and gelatin beads were dissolved by incubation at 37 °C and changing cell culture media.

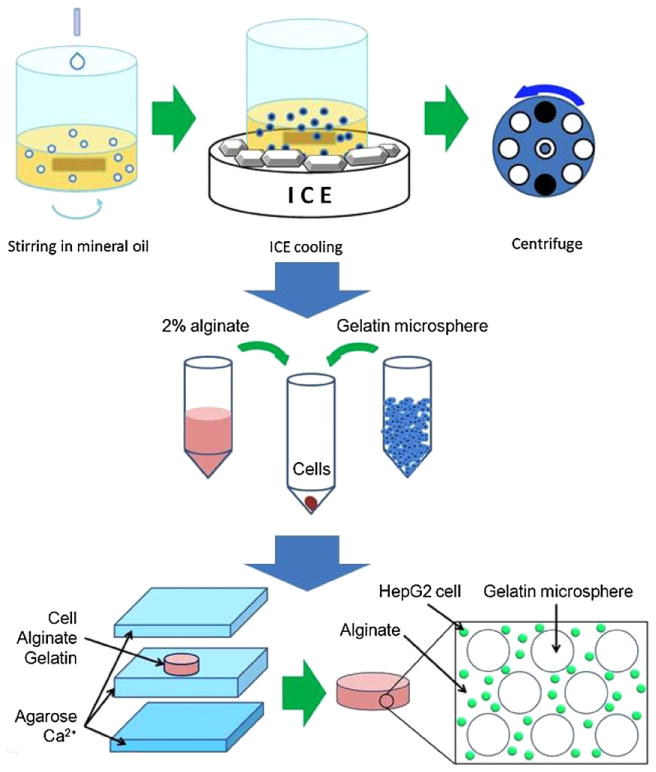

Figure 1.

Schematics of the fabrication process for porous cell-laden alginate hydrogel. First, gelatin microspheres were prepared by adding 10% gelatin solution at 1 mL min−1 into mineral oil under stirring at 600 rpm and by gelling in ice bath. Cells were mixed with the alginate solution and varying gelatin microsphere volume ratios. This solution was then molded into uniform disk-shaped hydrogels using Ca2+-containing agarose molds.

Compression test of the hydrogels

Uniaxial compression was performed to measure the mechanical properties of the alginate gels with an Instron 5542 mechanical tester (Norwood, MA). Disk-shaped alginate hydrogel samples without cells (D = 10 mm and h = 2 mm) were prepared with different gelatin contents as described above. Then, hydrogel samples were kept in a 37 °C water bath for 3 days to ensure complete dissolution of gelatin beads and formation of pores in the gels. During the compressive uniaxial test, the initial strain rate was set at 10% of original thickness and the crosshead speed was 200 μm min−1. Five specimens were tested for each porosity condition. Compressive moduli were calculated from the 5 to 10% strain region in the stress– strain curve. Values were reported as mean ± SD.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of the alginate hydrogels with different gelatin bead contents before and after dissolution of gelatin beads was investigated with SEM. Prior to SEM, fresh hydrogel samples were incubated in the water bath (37 °C) for 3 days with water being changed every 24 h. For SEM observation, hydrogel samples without cells were quenched in liquid nitrogen, brittle fractured and freeze dried for 72 h [8]. The freeze-dried samples were sputter coated with palladium–platinum alloy target materials with 40 mA current for 80 s prior to SEM morphological examination. The surface morphology of the cross-section of fractured alginate hydrogels was characterized with a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE SEM) Ultra 55 (Carl Zeiss, Inc. Thornwood, NY) with an operating voltage at 5 kV.

Permeability evaluation

Hydrogel samples (D = 25 mm, h = 1 mm) were assembled with a holder and gaskets for the permeability test. Permeability samples were placed in the middle of two flat gaskets with 10 mm diameter opening. One side of specimens was filled with water for pressure generation by 120 cm high water column. Water collecting container was placed at the distal end of the sample holders and the flow rate was calculated by measuring container weight change. Flow rate measurement was repeated five times for each sample and in total three samples were used for each porosity condition.

Permeability was converted according to Darcy's law in permeability, which is an analog of Navier–Stokes equation on the steady-state unidirectional flow in a uniform medium [27, 28]:

Here, Q is the volumetric flow rate of water measured (m3 s−1), Pu − Pd is the pressure difference in the upstream part and distal part of the samples (Pa), which is generated by water column height in this experimental setup, μ is the dynamic viscosity of the water (9.42 × 10−4 Pa s for dH2O at 23 °C), A is the cross-sectional area of the alginate specimen (m2) and L is the hydrogel specimen thickness (m). The intrinsic permeability coefficient K is independent of the nature of the fluid but depends on the geometry of the porous medium [28].

HepG2 encapsulation in porous alginate hydrogels

Human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium (DMEM, GibcoBRL) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, GibcoBRL) with 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin and 100 units mL−1 penicillin (GibcoBRL).

Cell-laden alginate hydrogels were prepared as described before. Gelatin bead volume was adjusted to 0, 30, 50, 80% (gel 0, gel 30, gel 50 and gel 80) and cell concentration was adjusted to 5 × 106 cells mL−1 with respect to final alginate–gelatin mixture volume. After gelling, each cell-encapsulated hydrogel sample was moved to a 24-well plate. Two milliliters of cell culture medium was added and plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. During cell culture, DMEM containing 200 mg L−1 calcium ion was used for cell culture medium to stabilize alginate gels. The medium was changed daily.

Cell distribution, viability and proliferation

For observation of cell distribution, cell membranes were labeled with the PKH67 green fluorescent cell linker kit (Sigma) before mixing with alginate. In brief, harvested cell pellet was suspended in 1 mL of diluents C and then 2 μL of PKH67 linker was added and incubated at room temperature for 5 min according to the manufacturer's instruction. Centrifuged cells were mixed into the alginate solution and gelled as described above. Cell distribution was observed with a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). At day 7, cytosol of live cells was observed after fluorescence staining with 2 μM calcein-AM for 20 min at 37 °C.

A Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) was used to evaluate 3D distribution of cells and reconstruction of porous and nonporous hydrogel structures (supplementary movies S1(a) and (b) available at stacks.iop.org/BF/2/035003/mmedia).

For cell viability evaluation, the live/dead cell viability kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used and samples were incubated with DPBS containing 2 μM calcein-AM and 4 μM ethidium homodimer for 10 min (37 °C, 5% CO2). The cell viability was reported as the ratio of the number of live cells to the total number of cells in each fluorescent image counted with the ImageJ software (NIH, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html). Live and dead cells were observed as green and red, respectively, by using the inverted fluorescence microscope. Live cells with green fluorescence in cytosol or dead cells with red fluorescence in nuclei were counted from six fluorescence images of each condition, and the sum of live and dead cells was used as the total cell number. The green and red images were converted to images with gray level intensities and were thresholded to generate a binary image containing all individual and aggregates of cells. The individual cells then were located and the number of cells was computed by the particle counting method.

Cell proliferation was analyzed by the mitochondrial activity assay with WST-1 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). On the predetermined day, 500 μL cell culture medium and 50 μL of WST-1 reagent was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The absorbance was measured with a microplate reader at 440 nm with 650 nm as a reference wavelength (n = 3 for each condition).

HepG2 spheroid measurement

After culturing cell-encapsulated hydrogels for 30 days, the area and area distribution of HepG2 spheroids were measured. The spheroid cross-sectional area was measured using the ImageJ software with optical microscopic images of control and porous hydrogels. From each porosity condition, the cross-sectional area of 600 spheroids (in focus) was measured from multiple phase contrast images. Measured spheroids were classified into intervals of 200 μm2 area and the percent spheroid area was plotted against these intervals.

The percent spheroid area of each interval was calculated as

Here, k is the number of spheroids in each interval and sum of spheroid size in each interval was divided by sum of all the spheroid sizes measured (n = 600). Also, percent spheroid coverage in each gel was calculated as the ratio of the total area occupied by spheroids to the total hydrogel area (n = 10 images).

Determination of metabolic activities

Albumin secreted by HepG2 was assayed using an ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., USA) that utilized human-specific albumin antibodies. In brief, culture media from the hydrogel samples were collected every 24 h and filtered before the assay. Enzyme-linked substrate microwell plates were prepared by a sequential procedure: pre-coating, enzyme linkage, post-coating and fluorescence dye linking. Before changing each step, all the wells were washed three times with washing buffer. The absorbance was measured with the ELISA reader at 450 nm and the albumin concentration was calculated using a calibration curve of known amounts of calibration albumin supplied in the ELISA kit.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons between two groups were done using Student's paired t-test while multiple comparisons were done using one-way ANOVA. Differences at a p-value less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant unless otherwise noted. All error bars were presented as standard deviations.

Results and discussion

Adequate hydrogel porosity design is important for cell–cell interaction, migration, proliferation and exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste materials in and out of the hydrogels. Another important parameter for improved cell function is appropriate 3D microenvironmental cues. Hence, it may be essential to develop methods to generate pores that allow simultaneous encapsulation of cells inside the hydrogels using mild cell-compatible conditions and form 3D structure in short time [9, 18, 23, 29, 30]. Here, we used gelatin beads as template for creating pores in cell-laden alginate hydrogel. We further characterized these hydrogels for enhanced permeability and their ability to maintain cell viability, proliferation and cellular function using encapsulated HepG2 cells.

Fabrication of alginate hydrogels using agarose molds

To create uniform disk-shaped alginate hydrogels, a simple molding approach using agarose molds was designed as depicted in figure 1. Cell–gelatin–alginate mixtures cast in the Ca2+-ion-releasing agarose molds were crosslinked from top, bottom and perimeter of the agarose mold by diffusion of Ca2+ ions from the molds in several seconds. Gel 0 and gel 30 samples gelled in 10 min, whereas gel 50 and gel 80 samples required longer gelation time of about 30 min. Alginate hydrogel in gel 50 and gel 80 condition needed more time for higher degree of crosslinking for handling without structural failure. This gelling time difference was due to diffusion of Ca2+ ions from agarose molds to alginate. At higher gelatin contents, diffusion of Ca2+ ions was limited by the gelatin beads in the mixture, because the diffusion was slower in semi-solid gelatin beads than in the liquid-phase alginate solution. Figure 2(f) shows homogeneous porous structure throughout the hydrogel. This reflects the negligible effect of long crosslinking time on microstructural homogeneity.

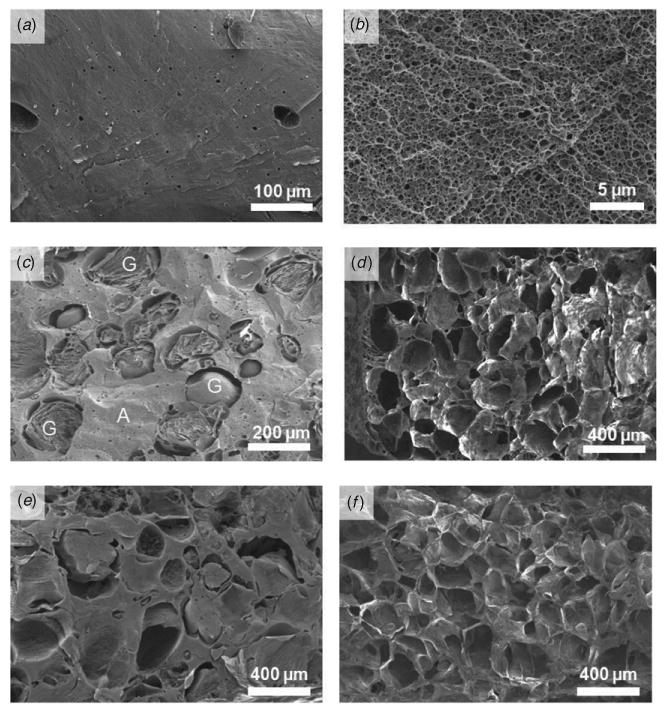

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs showing alginate hydrogels (labeled as A) with or without gelatin beads (labeled as G). Alginate hydrogel (2% w/v) without gelatin beads; (a) alginate has no macroscopic pores and (b) intrinsic porous structure with submicron size pores. Alginate hydrogel with 50% volume fraction of gelatin beads before (c) and after (d) pore generation. Alginate hydrogel with 80% volume fraction of gelatin beads before (e) and after (f) pore generation.

For this study, it was also essential to maintain gelatin bead integrity during alginate gel fabrication at room temperature. Hence, the porcine gelatin solution with 10% w/v concentration was chosen after testing the stability of the beads with different gelatin concentrations at room temperature. Gelatin beads prepared with 10% w/v porcine gelatin were stable at room temperature without significant dissolution or distortion. To further avoid the dissolution of gelatin beads during porous cell-laden hydrogel fabrication, gelatin beads at 4 °C were mixed with an ice-cold alginate solution. This delayed equilibration of beads and their dissolution at room temperature maintaining their integrity although alginate hydrogels were fabricated at room temperature. The SEM images presented in figures 2(c) and (e) clearly showed integrity of the gelatin beads immediately after alginate gel fabrication and before their dissolution at 37 °C.

Microstructure of alginate hydrogels

From the SEM observation of the cross-section, control alginate hydrogels without gelatin beads showed a porous structure with submicron size interconnected pores as shown in figure 2(b). The intrinsic pore structure may be formed during dehydration of alginate hydrogel; the original pore size should be smaller than this size due to hydration of the alginate matrix. When mixed with the alginate solution, gelatin beads were dispersed in the alginate matrix homogeneously and had a spherical shape as revealed from SEM images (figures 2 (c)–(f)). Without alginate hydrogel, gel state gelatin beads in HBSS or PBS dissolved within 30 min when incubated at 37 °C. The gel to sol physical transformation phenomenon would be the same for encapsulated gelatin beads inside the alginate gel at 37 °C given the fact that all conditions were kept constant. After dissolution, the diffusion of gelatin molecules will be dependent on the mass transfer inside alginate gels. Indeed, the SEM images revealed empty spaces that were generated after gelatin removal (figure 2(c) compared with 2(d) and 2(e) compared with 2(f)). With high gelatin bead content (gel 80), alginate hydrogels had a highly porous microstructure as shown in figure 2(e). Tissue engineering scaffolds adopt porogen size for effective cell adhesion, migration and proliferation. This size range varies with cell type and target organs [31, 32]. For instance, bone cells showed highest adhesion around a 120 μm pore size whereas highest proliferation at a 325 μm pore scaffold [32]. In this study, pores were introduced after cell encapsulation in alginate hydrogel. Cells resided in the bulk of alginate gels and gelatin beads dissolved to generate pores to enhance mass transfer of nutrients and oxygen and metabolic wastes of cells. Even larger or smaller porogens could be used for a similar effect as long as similar permeability to metabolite molecules is achieved. Hence, here we used 150–300 μm size porogens and increased the porosity by increasing their amount in the scaffolds without changing the pore size. Keeping in mind that the aim was to study the effect of overall porosity, the pore sizes were kept constant. It is worthwhile to note that the pore sizes were similar to gelatin bead sizes. Thus, alginate hydrogel scaffolds with controlled porosity and pore sizes could be successfully fabricated using gelatin beads. This porous structure can enhance medium exchange and diffusion of oxygen, nutrients and metabolic wastes maintaining higher cell viability of multicellular HepG2 spheroids. In conventional polymeric scaffolds, the cells are seeded after pore generation. This limitation is due to the cell incompatible scaffold preparation process, such as use of organic solvents or high temperature, and consequently, cells cannot be mixed during scaffold fabrication. In this process, cells reside in the pores and not in the bulk of the hydrogel. It is also difficult for cells to reach inside the bulk of the scaffolds homogeneously [33]. In contrast, in the method proposed here, cells were mixed with hydrogel material before gelling and evenly distributed throughout the scaffold in 3D (supplementary movie S1 stacks.iop.org/BF/2/035003/mmedia). Thus, advantages of the gelatin bead leaching method are several fold. It is a simple method. It can be used to encapsulate cells due to the benign conditions used during hydrogel preparation. Porosity and pore sizes can be tuned by adjusting the volume ratio and size of gelatin beads, to generate uniform and controllable porosity. At the same time, porous structure can support higher mass transfer rate and cell growth unlike other pore generation methods where cells are seeded on the surface of the already created porous scaffolds [23, 34, 35].

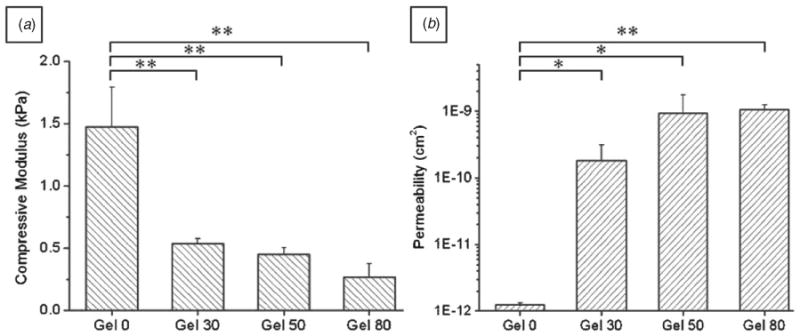

Mechanical properties

To analyze the mechanical properties of the scaffolds, compressive moduli were measured from the stress–strain curves of the uniaxial compression test. Compressive moduli of porous alginate hydrogels decreased significantly with increasing porosity as shown in figure 3(a). The alginate hydrogel modulus without pores was 1.5 ± 0.3 kPa, which was comparable with values reported previously [21]. On the other hand, LeRoux et al have reported higher compressive moduli (8–12 kPa) for 2% alginate hydrogels [36]. The difference in compressive moduli may be due to different crosslinking methods. In their process, the crosslinking was done in a calcium chloride solution for 90 min, whereas in our case, hydrogels were crosslinked using calcium ion diffusion from agarose molds only for 10 min. Addition and subsequent dissolution of gelatin microspheres in gel 30, gel 50 and gel 80 resulted in 63.4, 69.5, 81.6% decrease in compressive moduli respectively compared to nonporous hydrogel (gel 0). The pores resulted in reduction of the effective cross-sectional area, which maintains original structure under external stress. Our findings are in accordance with the other reports where increasing porosity resulted in a decrease in compressive moduli [37]. Such a decrease in mechanical properties can limit the use of these hydrogels for soft tissue engineering applications. Thus, these data suggest that a proper balance between the porosity and desired mechanical properties should be maintained for desired tissue engineering applications.

Figure 3.

(a) Compressive moduli of porous alginate hydrogels. Values were determined from the 5 to 10% strain region of the stress–strain curve (n = 5, mean ± SD). (b) Permeability of porous alginate hydrogel. Permeability was measured by the water column method with 120 cm H2O pressure difference. Water permeability increased about 500 times for porous alginate hydrogel. Highly porous alginate hydrogel (gel 80) showed high water flow rate and permeability (n = 3, mean ± SD). For both experiments, one-way ANOVA showed a significantly different trend across the groups (p < 0.01), whereas between group comparisons were done by Student's paired t-test, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Mass transfer in porous hydrogel

Hydrogels have superior permeability compared to dense synthetic polymers, such as polylactide (PLA) and polyglycolide (PGA). This characteristic enables hydrogels as promising candidates for cell-laden tissue engineering matrices [1, 19, 28]. The mass transfer of soluble factors from culture medium in vitro or blood in vivo is advantageous if highly permeable scaffolds are used for 3D tissue construct formation [1, 28].

As shown in figure 3(b), water flow rate and intrinsic permeability increased several orders of magnitude under porous conditions. The measured water flow rate in gel 0 was found to be 0.7 ± 0.03 μL min−1, whereas gel 30, gel 50, gel 80 samples showed flow rates of 67.1 ± 24.1, 466 ± 202 and 537 ± 106 μL min−1, respectively (n = 3, each averaged from 5 measurements). The flow resistance decreased by increasing porosity in the hydrogels. The intrinsic permeability of samples also increased from 1.2 ± 0.1 × 10−12 cm2 for gel 0 to 1064 ± 180 × 10−12 cm2 for gel 80 samples. It is worthwhile to note that well-developed porous structure dramatically enhanced (90– 720 times) permeability of water in porous structures with increasing gelatin content (figure 3(b)) [28].

Since the distribution of metabolites in the scaffolds depends on the convective and diffusive mass transfer, enhanced mass transfer can be widely applied in hydrogel-based tissue engineering [1, 4, 38, 39]. Thus, it is anticipated that such increased permeability will be beneficial to supply nutrients and remove metabolites enhancing cell viability and tissue formation.

Cell distribution, viability and proliferation

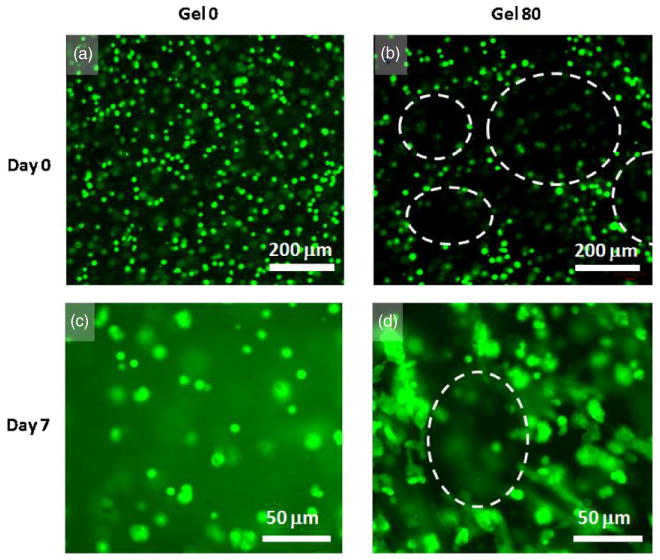

When cells are seeded on the preformed porous scaffolds, distribution of the cells in these scaffolds depends on their migration and proliferation inside the walls and pores of the scaffolds. In contrast, when cells are encapsulated inside the gel before gelation, homogeneous cell distribution can be achieved during cell seeding. This was evident in nonporous alginate hydrogel where cells distributed relatively homogeneously (figure 4(a)) and in porous hydrogels (supplementary information available at stacks.iop.org/BF/2/035003/mmedia). Hydrogels prepared with 80% gelatin beads (gel 80) showed large empty spaces in fluorescence observation (figure 4(b)). This was attributed to incorporated gelatin beads. As cells were mixed with alginate and gelatin beads before gelling, they remained in the bulk of alginate hydrogel. However, after culturing for several days, cells in the porous gel (gel 80) proliferated more than the control (gel 0), connected to the adjacent cells or form aggregates (figure 4(d)) and formed larger spheroids (figure 7(c)).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence microscopic images of cell distribution in the hydrogels; cell membrane was labeled with a fluorescent dye (green). Distribution of cells immediately after gelling in the nonporous alginate hydrogel at day 0 (a) and after 7 days in culture (c); in porous gel 80 at day 0 (b) and after 7 days in culture (d). Dashed lines in (b) and (d) illustrate the boundaries of pores in porous gel 80 samples. Cells were closely associated with each other and distributed in the alginate walls at day 0. Cells in the nonporous gel 0 hydrogel remained rounded even after day 7 whereas those in porous gel 80 samples show cell to cell contact and spreading. 3D movie images of confocal microscopy of cell distribution in porous and nonporous hydrogels are available in the supplementary data at stacks.iop.org/BF/2/035003/mmedia.

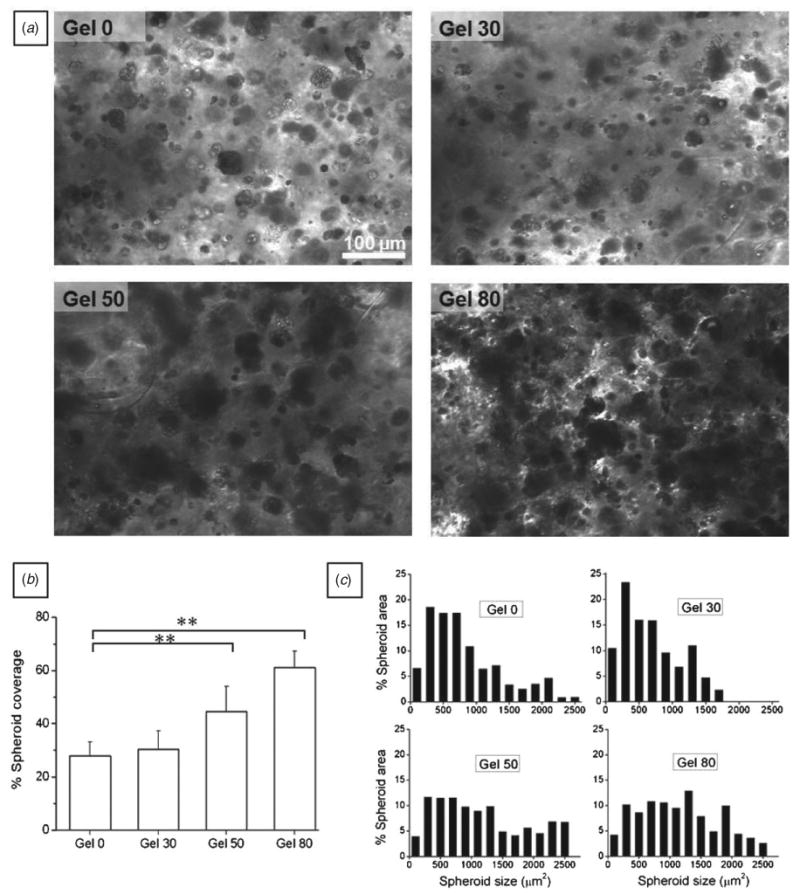

Figure 7.

HepG2 spheroid formation after 30 days in culture. (a) Microscopic view of HepG2 spheroids in different alginate hydrogels after 30 days in culture. The spheroids occupied more hydrogel area in gel 50 and gel 80 as compared to gel 0 and gel 30. (b) Bar graph showing spheroid coverage in the hydrogels; hepatic spheroids occupied smaller area in gel 0 and gel 30 compared to higher porosity conditions (mean ± SD, n = 10 images, one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001). Spheroids occupied significantly higher area in gel 50 and gel 80 samples compared to gel 0 (Student's paired t-test, ** p < 0.01). (c) Histogram showing the % spheroid area (μm2) occupied by each size range compared to the total spheroid area; area occupied by larger size spheroids increased with porosity.

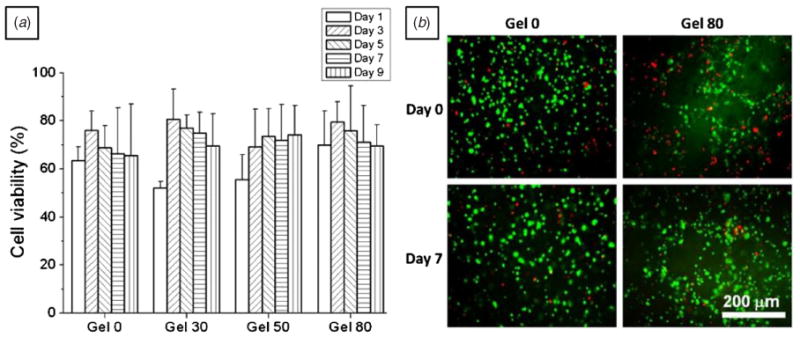

Figure 5 shows results obtained for cell viability with live/dead cell viability assay kit and cell proliferation with WST-1 during 9 days of culture. Cell viability in control nonporous and porous alginate hydrogels was not significantly different (ANOVA, p > 0.05). After initial cell encapsulation, overall cell viability ranged from 67 to 84%, which was similar to previous reports [35]. It should be noted that incorporated gelatin did not show any significant cytotoxicity during HepG2 culture [29, 40] and human embryonic stem cell culture [41], as reported previously.

Figure 5.

Cell viability of HepG2 liver cells for 9 days in culture. (a) Bar graphs showing cell viability and (b) fluorescence microscope images showing live (green) and dead (red) cells on days 0 and 7. Cell viability on different days was not significantly different within all the hydrogels (for each porosity condition, three hydrogel discs were evaluated for cell viability. For each hydrogel disk, at least six different images were counted, one-way ANOVA, p > 0.05).

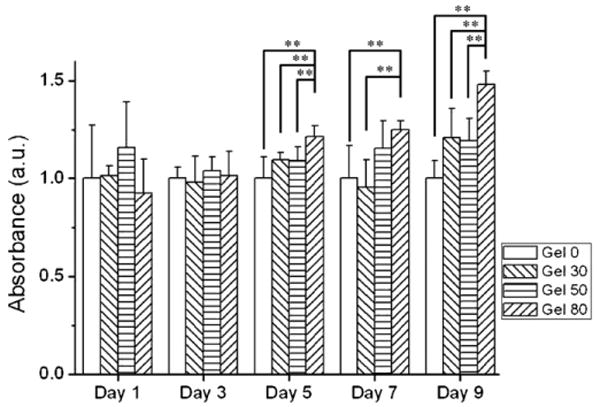

Porous microenvironment of alginate hydrogels also improved cell proliferation of HepG2 cells as shown in figure 6. Cell proliferation was significantly higher in porous hydrogels, especially gel 80 samples as compared to gel 0 and gel 30 samples (p < 0.01, Student's paired t-test) after 5 days in culture. These results imply that porosity may be important in enhancing the cell proliferation and maintaining cell viability. Thus, pores formed due to dissolution of gelatin may have enhanced mass transfer of molecules necessary for maintaining cell viability and proliferation. Also, the pore space may have provided room for cells growing on top of each other and resulted in higher cell proliferation as shown in figure 6 [9, 14, 34]. Improved cell proliferation may also be explained by the possible coexistence of gelatin chains inside the bulk of the alginate hydrogels before its complete diffusion out of the hydrogel. It is probable that some gelatin chains may have diffused inside the alginate hydrogel during its dissolution and diffusion. These gelatin chains, which contain sequence necessary for cell adhesion and growth, might play a role in enhancing cell spreading and proliferation seen in figures 4(d) and 5. Indeed, Sakai et al have recently shown that cells embedded in covalently modified agarose–gelatin hollow microcapsules exhibited faster proliferation and aggregation than unmodified agarose gel [42]. This was attributed to the adhesiveness of the agarose–gelatin microcapsule membrane. Similarly, Schagemann and colleagues have reported that chondrocytes proliferated and differentiated into their spheroidal phenotype in alginate–gelatin hydrogel beads [43]. This suggests that observed improvement in cell proliferation may be in part due to the remaining gelatin content in the bulk of the alginate hydrogel.

Figure 6.

Cell proliferation of HepG2 by mitochondrial activity assay (WST-1) in porous alginate hydrogels. Data were normalized to control alginate hydrogel for each measurement. Mitochondrial activity significantly increased in gel 80 compared to control gel 0 condition after day 5 (mean ± SD, n = 6, Student's paired t-test, ** p < 0.01).

HepG2 spheroid formation

It has already been reported that multicellular spheroid formation with 3D structures is an important step in maintaining hepatocellular functions [9, 18, 23, 29, 30]. This cell aggregation is mediated by stronger cell–cell interactions compared to cell–matrix interactions. Hence, non-adhesive alginate was chosen as bulk hydrogel material. It was interesting to study how the porous structure and enhanced permeability affected the size of the spheroids. Therefore, HepG2 cells were cultured for 30 days under static conditions and the cross-sectional area of different aggregates was measured for different porosity samples. As shown in figure 7(a), size and number of cell aggregates in the gel 0 and gel 30 were significantly less developed compared to gel 50 and gel 80 conditions. Also, it was evident that spheroids covered higher area of optical field in gel 50 and gel 80 samples than gel 0 and gel 30 samples. Further quantification of percent spheroid coverage showed significant differences in alginate hydrogels with different porosities as shown in figure 7(b) (ANOVA, p < 0.001). For instance, percent spheroids coverage was 27.8 ± 5.3% of total area in gel 0, whereas 44.5 ± 9.5% and 61.1 ± 6.2% in gel 50 and gel 80, respectively. Indeed, gel 80 samples showed a twofold increase in percent spheroid coverage value in comparison to gel 0 samples. Changes in the spheroid size are also evident from figure 7(c) where the percent spheroid area was plotted against size. Alginate hydrogels with a high gelatin porogen content showed higher proportion of large spheroids compared to gel 0 and gel 30 samples. The percent spheroid area occupied by large aggregates increased in gel 50 and gel 80 hydrogels.

Interestingly, the number of cells incorporated in the gel was similar for each condition and the cells resided inside the hydrogel matrix. Thus, introduction of pores reduced the intercellular distance in gel 50 and gel 80 compared to gel 0 samples. Cells could contact each other due to short distance and could form bigger aggregates. It is worthy to note that despite their large size, these aggregates maintained their cell viability (figure 5) and showed enhanced proliferation (figure 6). This may be attributed to higher porosity causing improved mass transfer rate of oxygen and metabolites. Also, as discussed in the previous section, gelatin molecules from dissolving beads might have diffused inside the alginate hydrogels and contributed to the enhanced spheroid formation as reported by others in the case of cells embedded in microcapsules [42, 43].

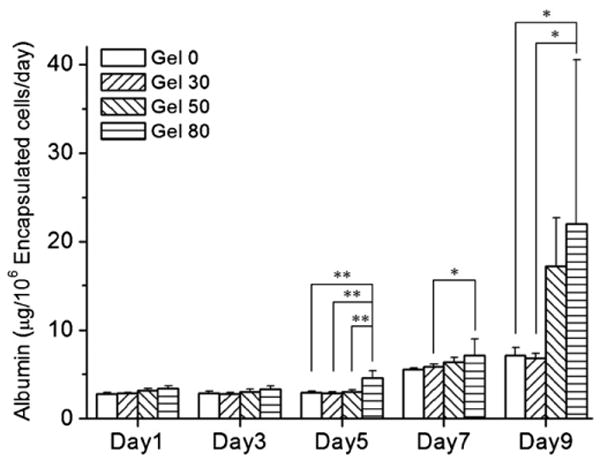

Albumin assay

Albumin concentrations measured from each condition are summarized in figure 8. Albumin secretion by spheroids increased with time in all the hydrogels up to day 9. HepG2 cells seeded in nonporous alginate hydrogel (gel 0) also produced albumin with increasing tendency at day 9 compared to that at day 1 (figure 8). This may be attributed to the encapsulation of HepG2 cells inside the hydrogels providing the appropriate microenvironmental cues by the bulk of the alginate hydrogels. Indeed, Chang et al have recently shown that HepG2 cells respond differently to 2D and 3D environmental cues [30]. They found that HepG2 cells expressed high levels of ECM, adhesion molecules and cytoskeleton in 2D, whereas metabolic and functional genes were upregulated in 3D cultures [30].

Figure 8.

Analysis of albumin secretion by HepG2 spheroids encapsulated in porous and nonporous alginate. Spheroids encapsulated in hydrogels showed higher albumin secretion throughout the culture period. Higher porosity conditions enhanced albumin secretion further compared to nonporous gel 0. From day 5, gel 80 showed a significant difference compared to a nonporous condition (gel 0) (n = 3, mean ± SD, Student's paired t-test, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05).

It is further interesting to note that porous gel 80 hydrogels showed higher albumin secretion at day 9 compared to that at day 1. These hydrogels also showed a significant increase in albumin production over nonporous gel 0 condition at day 9 (figure 8). These results may be correlated with the number of cells and size of spheroids. It was observed that higher porosity conditions showed enhanced cell proliferation (figure 6) and produced spheroids occupying higher area fraction (figure 7(a)) than nonporous condition and, thus, showed enhanced albumin production. However, it should be noted that the relative mitochondrial activity level at day 9 was 1.5 times higher in gel 80 than in gel 0 (figure 6), whereas the albumin secretion was three times higher for gel 80 than for gel 0 (22.0 ± 18.5 versus 7.1 ± 0.93 μg/day per 106 encapsulated cells, respectively) (figure 8). Although our data showed enhanced albumin production by cells in higher porosity conditions, it is stressed that further tests such as urea production and cytochrome enzyme activity must be carried out to further application to liver tissue engineering.

In a nutshell, our study clearly illustrated the synergistic effect of porous hydrogel structure for 3D cell encapsulation. Encapsulation of cells inside the bulk hydrogels satisfied microenvironmental niche of HepG2 cells leading to larger spheroids with enhanced function. On the other hand, use of cell compatible gelatin beads for in situ pore generation sustained HepG2 viability, enhanced their proliferation and provided sufficient mass transfer for oxygen, nutrient and metabolites increasing albumin production for the cultured periods. There is a probability that traces of gelatin beads remaining in the bulk of the hydrogel might have played some role in enhancing cellular functions, although further studies are needed to prove this. Further mechanistic evaluation will also be undertaken to characterize ECM formation and gene expression by the cells in these porous hydrogels under prolonged culture conditions.

Conclusions

In this study, we suggested a method for pore generation in 3D cell-laden alginate hydrogels. The thermoresponsive gelling property of gelatin was exploited for uniform and controlled porosity using selected sizes (150–300 μm) of gelatin beads. This method enabled 3D encapsulation of cells as well as control of porosity simultaneously, leading to homogeneous distribution of cells throughout the thickness of alginate hydrogels. The permeability of alginate hydrogels increased around two orders of magnitude by introduction of porous structure as measured by the water column method. Further, these HepG2 cell-laden hydrogels showed enhanced cell proliferation, larger spheroid formation and higher albumin production compared to nonporous gels. The temperature-dependent gelling property of gelatin potentially has a good application for non-toxic pore generation in the presence of the cells. This strategy can be applied to cell-laden hydrogel-based 3D tissue engineering, combined with appropriate selection of gelling materials for regenerative tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the National Institutes of Health (EB007249; DE019024; HL092836), the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnology and the US Army Corps of Engineers. SS acknowledges the postdoctoral fellowship received from Fonds de Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies (FQRNT), Quebec, Canada.

Footnotes

Online supplementary data available from stacks.iop.org/BF/2/035003/mmedia

Author Disclosure Statement. CH and AK designed the study; CH performed gelatin bead preparation, cell culture, cell culture experiments and SEM; NK performed live/dead image analysis, MM and BZ performed the albumin assay; CH and SS analyzed data; CH and SS contributed equally to writing the manuscript; CH, SS and AK discussed the results; CH, SS, AK and SL commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Choi NW, Cabodi M, Held B, Gleghorn JP, Bonassar LJ, Stroock AD. Microfluidic scaffolds for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2007;6:908–15. doi: 10.1038/nmat2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, Peppas NA. Hydrogels in regenerative medicine. Adv Mater. 2009;21:1–23. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khetani SR, Bhatia SN. Microscale culture of human liver cells for drug development. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:120–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollister SJ. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2005;4:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X, Zhang Y, Donahue HJ, Lowe TL. Porous thermoresponsive-co-biodegradable hydrogels as tissue-engineering scaffolds for 3-dimensional in vitro culture of chondrocytes. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2645–52. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JS, Woo DG, Sun BK, Chung HM, Im SJ, Choi YM, Park K, Huh KM, Park KH. In vitro and in vivo test of PEG/PCL-based hydrogel scaffold for cell delivery application. J Control Release. 2007;124:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khutoryanskaya OV, Mayeva ZA, Mun GA, Khutoryanskiy VV. Designing temperature-responsive biocompatible copolymers and hydrogels based on 2-hydroxyethyl(meth)acrylates. Biomacromolecules. 2008;14:3353–61. doi: 10.1021/bm8006242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Pan J, Zhang L, Guo X, Yu Y. Culture of primary rat hepatocytes within porous chitosan scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67:938–43. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang VL, Chen AA, Cho LM, Jadin KD, Sah RL, DeLong S, West JL, Bhatia SN. Fabrication of 3D hepatic tissues by additive photopatterning of cellular hydrogels. FASEB J. 2007;21:790–801. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7117com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant SJ, Cuy JL, Hauch KD, Ratner BD. Photo-patterning of porous hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2978–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn MS, Taite LJ, Moon JJ, Rowland MC, Ruffino KA, West JL. Photolithographic patterning of polyethylene glycol hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2519–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsang VL, Bhatia SN. Three-dimensional tissue fabrication. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1635–47. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guillemot F, et al. High-throughput laser printing of cells and biomaterials for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2009;6:2494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Gunn J, Chen MH, Cooper A, Zhang M. On-site alginate gelation for enhanced cell proliferation and uniform distribution in porous scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:552–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SS, Sundback CA, Kaihara S, Benvenuto MS, Kim BS, Mooney DJ, Vacanti JP. Dynamic seeding and in vitro culture of hepatocytes in a flow perfusion system. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:39–44. doi: 10.1089/107632700320874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norotte C, Marga FS, Niklason LE, Forgacs G. Scaffold-free vascular tissue engineering using bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5910–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Y, Lo E, Ali S, Khademhosseini A. Directed assembly of cell-laden microgels for fabrication of 3D tissue constructs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801866105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Underhill GH, Chen AA, Albrecht DR, Bhatia SN. Assessment of hepatocellular function within PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2007;28:256–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling Y, Rubin J, Deng Y, Huang C, Demirci U, Karp JM, Khademhosseini A. A cell-laden microfluidic hydrogel. Lab Chip. 2007;7:756–62. doi: 10.1039/b615486g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang YS, Cho J, Tay F, Heng JY, Ho R, Kazarian SG, Williams DR, Boccaccini AR, Polak JM, Mantalaris A. The use of murine embryonic stem cells, alginate encapsulation, and rotary microgravity bioreactor in bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo CK, Ma PX. Ionically crosslinked alginate hydrogels as scaffolds for tissue engineering: part 1. Structure, gelation rate and mechanical properties. Biomaterials. 2001;22:511–21. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Familletti PC. Immobilization of cells in alginate beads containing cavities for growth of cells in airlift bioreactors. US Patent 5073491 1991

- 23.Dvir-Ginzberg M, Elkayam T, Cohen S. Induced differentiation and maturation of newborn liver cells into functional hepatic tissue in macroporous alginate scaffolds. FASEB J. 2008;22:1440–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9277com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bigi A, Panzavolta S, Rubini K. Relationship between triple-helix content and mechanical properties of gelatin films. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5675–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golden AP, Tien J. Fabrication of microfluidic hydrogels using molded gelatin as a sacrificial element. Lab Chip. 2007;7:720–5. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokuyama H, Kanehara A. Novel synthesis of macroporous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels using oil-in-water emulsions. Langmuir. 2007;23:11246–51. doi: 10.1021/la701492u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintard M, Whitaker S. Coupled, nonlinear mass transfer and heterogeneous reaction in porous media. In: Vafai K, editor. Handbook of Porous Media. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis; 2005. pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoch G, Chauhan A, Radke CJ. Permeability and diffusivity for water transport through hydrogel membranes. J Membr Sci. 2003;214:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma P, Verma V, Ray P, Ray AR. Agar–gelatin hybrid sponge-induced three-dimensional in vitro ‘liver-like’ HepG2 spheroids for the evaluation of drug cytotoxicity. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:368–76. doi: 10.1002/term.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang TT, Hughes-Fulford M. Monolayer and spheroid culture of human liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell line cells demonstrate distinct global gene expression patterns and functional phenotypes. Tissue Eng A. 2009;15:559–67. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M, Wu BM, Dunn JC. Effect of scaffold architecture and pore size on smooth muscle cell growth. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:1010–6. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy CM, Haugh MG, O'Brien FJ. The effect of mean pore size on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:461–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haroun AA, Gamal-Eldeen A, Harding DR. Preparation, characterization and in vitro biological study of biomimetic three-dimensional gelatin-montmorillonite/ cellulose scaffold for tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:2527–40. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerecht-Nir S, Cohen S, Ziskind A, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Three-dimensional porous alginate scaffolds provide a conducive environment for generation of well-vascularized embryoid bodies from human embryonic stem cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88:313–20. doi: 10.1002/bit.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho SH, Oh SH, Lee JH. Fabrication and characterization of porous alginate/polyvinyl alcohol hybrid scaffolds for 3D cell culture. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2005;16:933–47. doi: 10.1163/1568562054414658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeRoux MA, Guilak F, Setton LA. Compressive and shear properties of alginate gel: effects of sodium ions and alginate concentration. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:46–53. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199910)47:1<46::aid-jbm6>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidalgo-Bastida LA, Barry JJ, Everitt NM, Rose FR, Buttery LD, Hall IP, Claycomb WC, Shakesheff KM. Cell adhesion and mechanical properties of a flexible scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:457–62. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boland T, Xu T, Damon B, Cui X. Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:910–7. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337–51. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adhirajan N, Shanmugasundaram N, Shanmuganathan S, Babu M. Functionally modified gelatin microspheres impregnated collagen scaffold as novel wound dressing to attenuate the proteases and bacterial growth. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;36:235–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saeki K, Nakahara M, Matsuyama S, Nakamura N, Yogiashi Y, Yoneda A, Koyanagi M, Kondo Y, Yuo A. A feeder-free and efficient production of functional neutrophils from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:59–67. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakai S, Hashimoto I, Kawakami K. Agarose–gelatin conjugate membrane enhances proliferation of adherent cells enclosed in hollow-core microcapsules. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19:937–44. doi: 10.1163/156856208784613587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schagemann JC, Mrosek EH, Landers R, Kurz H, Erggelet C. Morphology and function of ovine articular cartilage chondrocytes in 3-d hydrogel culture. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;182:89–97. doi: 10.1159/000093063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]