Abstract

P-Rex1 (Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1) is a Rac-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor activated by Gβγ subunits and by PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Recent studies indicate that P-Rex1 plays an important role in signaling downstream of neutrophil chemoattractant receptors. Here we report that heterologous expression of P-Rex1, but not Vav1, reconstitutes formyl peptide receptor (FPR)-mediated NADPH oxidase activation in the transgenic COSphox cells expressing gp91phox, p22phox, p67phox and p47phox. A successful reconstitution requires the expression of a full-length P-Rex1 with intact DH and PH domains, and is accompanied by P-Rex1 membrane localization as well as Rac1 activation. P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation in the reconstituted COSphox cells was further enhanced by expression of the novel PKC isoform PKCδ and by overexpression of Akt. Heterologous expression of P-Rex1 in COSphox cells potentiated fMet-Leu-Phe-induced Akt phosphorylation, whereas expression of a constitutively active form of Akt enhanced Rac1 activation. In contrast, a dominant negative Akt mutant reduced the fMet-Leu-Phe stimulated superoxide generation as well as Rac1 activation. These results demonstrate that in COSphox cells, p-Rex1 is a critical component for FPR-mediated signaling leading to NADPH oxidase activation, and there is a crosstalk between the p-Rex1-Rac pathway and Akt in superoxide generation.

Keywords: P-Rex1, Rac GTPase, Guanine nucleotide exchange factor, NADPH oxidase

1. Introduction

The NADPH oxidase in phagocytic leukocytes plays a crucial role in host defense through its ability to convert molecular oxygen to superoxide, the precursor of microbicidal oxidants [1]. The redox center is a heterodimeric flavocytochromeb558 comprised of two integral membrane proteins, gp91phox and p22phox. Activation of electron transfer from NADPH to molecular oxygen requires recruitment of the cytosolic oxidase subunits p47phox and p67phox as well as the activated small GTPase Rac [2, 3]. Genetic mutations that affect the expression and/or functions of these proteins have been identified, which underlies clinical manifestation of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) due to failed production of superoxide [4, 5]. In addition to fulfilling the host defense functions in phagocytes, NADPH oxidase plays important roles in cell signaling and, when activated inappropriately, can cause tissue damage. Therefore, understanding the regulatory mechanisms for NADPH oxidase activation is of great importance in controlling inflammation and strengthening host defense.

Two major approaches have been taken to identify the components and activation mechanisms of phagocyte NADPH oxidase. The loss-of-function approach was first used in studies of CGD patients with recurrent infections. Combined with molecular cloning and DNA sequencing, this approach has resulted in the identification of more than 400 genetic mutations in phagocyte NADPH oxidase proteins [4, 5]. More recently, targeted deletion of genes coding for specific NADPH oxidase components has led to the use of mouse models (p47phox-/- and gp91phox-/-) for study of phagocyte NADPH oxidase [6, 7]. Deletions of the mouse Rac2 gene have led to the identification of its important function in the generation of superoxide in neutrophils [8]. Whereas the loss-of-function approach emphasizes the necessity of a given protein for a biological process, the gain-of-function approach stresses the sufficiency for a specific activity by providing a key component that is otherwise missing from a reconstitution system. In broken cell and cell-free reconstitution assays, inclusion of the membrane components, the cytosolic factors, activated Rac and an amphiphile such as SDS is sufficient for reconstitution of the NADPH oxidase [9-12]. However, the same assays also showed that p47phox is not required for superoxide production [13], a conclusion that differs from observations made using intact phagocytes. Whole-cell based reconstitution assays such as those using transgenic K562 cells and neutrophil “cores” [14, 15] provide the advantage of investigating the NADPH oxidase components in a cellular environment, where interactions with signaling molecules and cytoskeletal proteins may influence superoxide production as in neutrophils.

COSphox is a transgenic COS-7 cell line stably expressing the essential NADPH oxidase proteins gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox and p67phox [16]. Since COS cells are readily transfectable, different NADPH oxidase components and the effects of their mutations may be assessed in the COS-7 based reconstitution assays. Like neutrophils, COSphox responds to phorbol ester stimulation with potent superoxide production. However, the epithelial cell line lacks many signaling molecules that are abundant in neutrophils. For instance, reconstitution of fMLF-induced superoxide production not only requires heterologous expression of the formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1), but also depends on the expression of signaling molecules such as PKCδ [17, 18]. To better understand the receptor-mediated NADPH oxidase activation mechanisms in COSphox cells, we examined the requirement for guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that activate the Rac small GTPase. The specific guanine nucleotides exchange factors (GEFs) that regulate phagocyte NADPH oxidase have not been clearly defined. Recent studies indicate that P-Rex1 and Vav1, members of the Dbl family GEFs, participate in chemoattractant-induced production of superoxide [19-21]. P-Rex1 is a Rac-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor modulated by both Gβγ proteins and the lipid second messenger phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), through the interactions with its DH and PH domains, respectively [22]. In addition to the tandem DH-PH domain, P-Rex1 contains two DEP and PDZ domains and an InsPx 4-phosphatase (IP4P) domain. P-Rex1 is expressed primarily in myeloid cells and in nervous tissue, and is known to regulate inflammation and neuronal development. Studies using P-Rex1-deficient mice have shown that it is involved in the regulation of chemoattractant-induced Rac activation, chemotaxis, and production of superoxide in neutrophils [20, 21]. P-Rex1 is regulated by various signaling pathways for its activation and membrane translocation [23]. Another GEF for Rac, Vav1, has also been reported as being necessary for the fMLF-induced superoxide generation in mouse neutrophils [19]. It is presently unknown whether heterologous expression of P-Rex1 or Vav1 is sufficient for NADPH oxidase activation in reconstituted COSphox cells. The current study compares these two Rho-GEFs and other signaling molecules in the relevant signaling pathways for their respective functions in a gain-of-function assay for NADPH oxidase activation. Our results demonstrated that P-Rex1, but not Vav1, is necessary and sufficient for the reconstitution of fMLF-induced NADPH activity in COSphox cells. Our study also identifies a potential feedback mechanism between the PI3K-Akt and P-Rex1-Rac pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The N-formyl peptide fMLF, PMA, and isoluminol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HRP and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were obtained from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and Akt inhibitor SH X were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The monoclonal anti-AU5, anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies were from Covance. The monoclonal anti-FLAG (M2) and monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Sigma. The anti-Akt and anti-phosphor-Akt (T308) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling. The monoclonal anti-Rac1 antibody was from BD Pharmingen. Human P-Rex1 gene fragment was kindly provided by Dr. Dianqin Wu (Yale University) and was subcloned into the pRK5 vector with an AU5 tag added to it N-terminal end. The mouse Vav1 was described previously [24].

2.2. Generation of Mutant P-Rex1

The mutant human P-Rex1 constructs consisting of WT, the isolated DH-PH domains (iDHPH) and two double mutants within DH domain P-Rex1(E56A/N238A) and iDHPH(E56A/N238A) were prepared based on domain boundary predictions made with Prosite software and was cloned with a 5′-flanking in-frame EcoRI site and methionine start codon, and with a 3′-flanking stop codon and XbaI restriction site. The P-Rex1 (E56A/N238A) and iDHPH (E56A/N238A) constructs were cloned using mutagenic primers. For microscopy experiments, full-length P-Rex1 was subcloned into pEGFP-C1 vector.

2.3. Cell culture and transient transfection

The transgenic COSphox cells were generated as described previously [16]. The stable cell line was maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained with limiting dilution in the presence of 0.2 mg/ml hygromycin (Sigma), 0.8 mg/ml neomycin (Invitrogen), and 1μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem). Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) was used for transient transfection of DNA into COSphox cells grown in a 90-mm diameter culture dish. Cells were analyzed 21–24 h after transfection.

2.4. Measurement of NADPH oxidase activity

COSphox cells were harvested with enzyme-free cell-dissociation buffer (Invitrogen), and washed once with 0.5% BSA/HBSS. Cells were then resuspended in PBSG (PBS containing 0.5mM MgCl2, 0.9mMCaCl2 and 7.5mM dextrose), and preincubated in the dark with 100 μM isoluminol and 40 U/ml HRP at 37°C for 5 min. Aliquot (200 μl) of the cells was added to the well and assayed for chemiluminescence (CL) at 37°C in a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The CL counts per second (CPS) was continually recorded after stimulation with fMLF.

2.5. Rac activation assay

Activation of Rac was determined as previously described [17], based on the affinity of Rac-GTP for the p21-binding domain (PBD) of PAK1 with some modification [25]. The PBD-GST fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain HB101 and purified. About 24 h post-transfection, COSphox cells were detached with dissociation buffer, washed, and resuspended in PBSG. The cells were then stimulated with 1μM fMLF or buffer control as indicated in the figures. Twenty micrograms of PAK1 PBD-GST recombinant protein was added, and cells were lysed by the addition of lysis/wash buffer (6 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaH2PO4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 2 mM PMSF, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail I (Calbiochem), 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 50 mM NaF. The lysate was cleared, 30 _l of glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) was added, and the binding reaction was conducted for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were pelleted and washed three times with wash buffer, and then finally resuspended in loading buffer. Aliquots of supernatant (Total-Rac) and pulldown samples (Rac-GTP) were analyzed by western blot.

2.6. Western blot analysis

COSphox cells were washed with HBSS and lysed with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris– HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 4 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin and 100 μg/ml phenomethanesulfonyl fluoride. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected for protein analysis and Western blot. Total protein concentration was determined by using a commercially available kit based on the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. For Western blot analysis, 20 μg of the cell extract proteins were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS/polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T), washed with TBS-T and incubated overnight with phospho-Akt (T308) antibody or other indicated antibodies. The membrane was washed and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000) in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T buffer for 1 h. Detection was carried out using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Paired Student's t test was performed to determine statistical significance. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. P-Rex1-dependent reconstitution of superoxide generation in COSphox cells

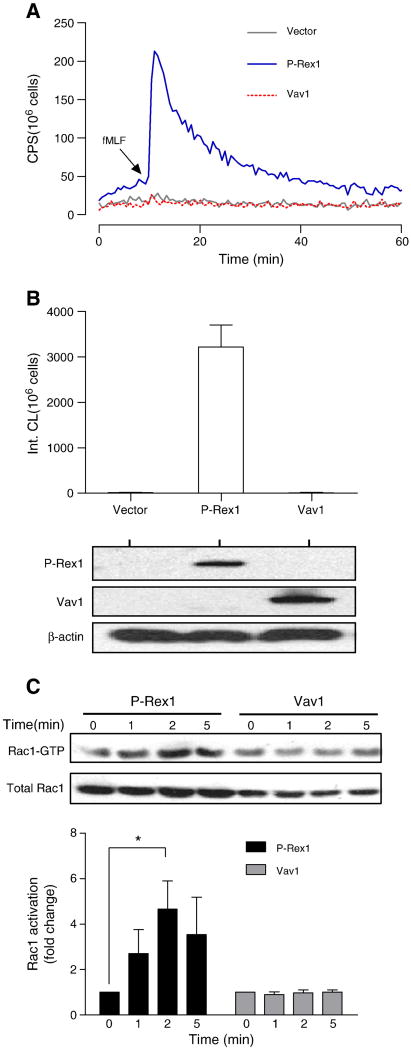

Previous studies have shown that the transgenic COSphox cells lack certain signaling components required for formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1)-mediated superoxide generation [17]. Since the small GTPase Rac is required for phagocyte NADPH oxidase activation, and P-Rex1 is an abundant GEF for Rac activation in leukocytes [22], we determined whether P-Rex1 is able to reconstitute fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation in the COSphox cell line. COSphox cells were cotransfected with expression vectors coding for human FPR1 and an AU5-tagged P-Rex1. For comparison, the cell line was cotransfected with a FLAG-tagged Vav1, a GEF known for its role in fMLF-induced superoxide production based on knockout studies [19]. After 24 h, the cells were stimulated with fMLF (1 μM), and superoxide production was monitored based on isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence [26]. As shown in Figure 1A, FPR- and P-Rex1-expressing COSphox cells responded to fMLF with a rapid production of superoxide without heterologous expression of additional neutrophil signaling molecules [17]. In contrast, cells expressing Vav1 did not produce significant amount of superoxide (Figure 1A, 1B).

Fig. 1.

P-Rex1-dependent reconstitution of fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation. COSphox cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for FPR and either P-Rex1 or Vav1. Superoxide production assays were conducted 24 h after transfection. (A) fMLF (1 μM)-induced superoxide production shown as changes in isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence (CL). CPS, counts per second. (B) Quantification of superoxide production based on integrated chemiluminescence (Int. CL) in the first 20 min after stimulation, shown as mean ± SEM from three experiments. The expression level of P-Rex1 and Vav1 was determined with Western blotting using antibodies against AU5 (for AU5-tagged P-Rex1) and FLAG (for FLAG-tagged Vav1). (C) Activation of endogenous Rac1 in COSphox cells after fMLF (1 μM) stimulation for the indicated time. The level of activated Rac1 (Rac1-GTP) was determined using RBD-GST pull-down assay. Total Rac1 was determined with Western blotting using an anti-Rac1 Ab. Densitometric analysis was performed to determine relative activation of Rac1 (Rac1-GTP pulled down, fold change compared to sample at time 0 in each group). Data were normalized against the total Rac1 expression level in 3 independent experiments, and are shown as mean± SEM. * P<0.05. Panel (A) of this figure is colored in the online version.

COSphox cells contain endogenous Rac1 but lack Rac2 [16, 27], and Rac1 activation is critical to the assembly of NADPH oxidase in COSphox cells [27]. Activation of the endogenous Rac1 was determined based on the ability of the N-terminal Rac binding domain (RBD) of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) to interact with GTP-bound Rac [25, 28, 29]. Results shown in Figure 1C demonstrate that fMLF induced a rapid and transient increase in Rac1 activation that peaked in 2 min. In comparison, hegerologous expression of Vav1 did not lead to inducible Rac1 activation. Expression of an active Vav1 in COSphox cells could stimulate superoxide production [16] (data not shown), suggesting that COSphox cells lack an upstream signaling molecule required for fMLF-induced Vav1 activation.

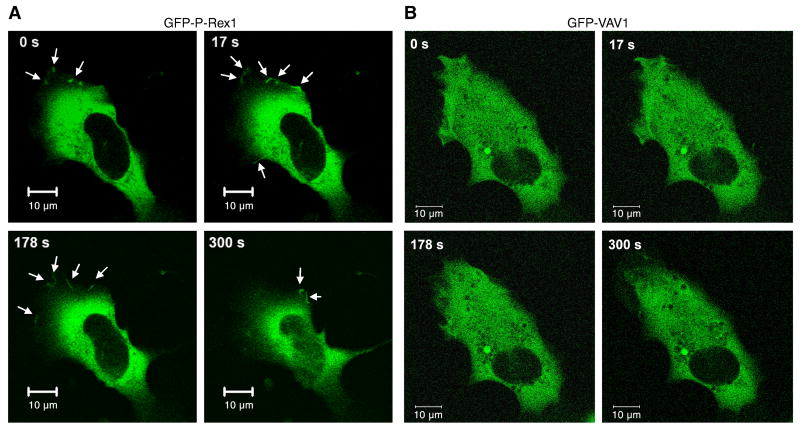

A recent study has shown that P-Rex1 is localized in the plasma membrane in activated neutrophils [23], which is believed to be important for P-Rex1-mediated Rac activation. To investigate P-Rex1 membrane localization in COSphox cells, we prepared a GFP-P-Rex1 construct and examine the redistribution of P-Rex1 using time-lapse fluorescent microscopy. The transfected COSphox cells were stimulated with fMLF (1 μM), and images were taken at a 3-second interval. P-Rex1 localization was primarily cytosolic in resting state, although a small amount of GFP-P-Rex1 was found at the cell periphery. Stimulation with fMLF increased the presence of the GFP-R-Rex1 protein in the cell periphery, suggesting membrane translocation (Figure 2A, arrows in upper panels). In contrast, A GFP-tagged Vav1, when expressed in the COSphox cells, remained intracellular in both unstimulated and stimulated conditions (Figure 2B). Control transfection with the EGFP-C1 vector showed exclusive intracellular localization of the GFP fluorescence (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

P-Rex1 membrane localization in reconstituted COSphox cells. COSphox cells were transfected with an expression vector for FPR and either the EGFP-P-Rex1 construct (A) or EGFP-Vav1 construct (B) or EGFP vector without cDNA insert (not shown). For each group, images of the same cells were taken at different time points after fMLF stimulation. Arrows indicate the appearance of EGFP fluorescence. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments on different days. Scale bar = 10 μm. A colored version of this figure is available online.

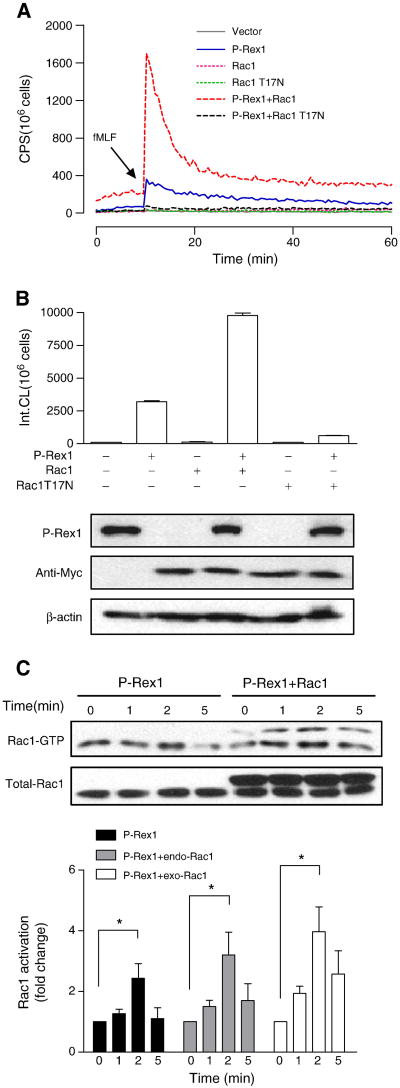

3.2. The fMLF-induced superoxide generation is Rac1-dependent

The small GTPase Rac is essential for NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils and in cell-free reconstitution assays [30, 31]. Our data suggested that FPR1 is able to use the endogenous Rac1 in COSphox cells for activation of NADPH oxidase, although published data show that P-Rex1 preferably activates Rac2 in neutrophils [21]. Expression of a dominant negative form of Rac1 (T17N) inhibited the fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation, while overexpression of Rac1 potentiated the P-Rex1-mediated superoxide generation (Figure 3A, 3B). In RBD pull-down assays, the kinetics of Rac1 activation remained the same when Rac1 is overexpressed, with peak activation at 2 min after fMLF stimulation (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

P-Rex1-mediated superoxide generation is Rac1-dependent. COSphox cells were cotransfected to express FPR, P-Rex1 and either the WT or T17N mutant of Rac1, both tagged with Myc. (A) fMLF-induced superoxide generation showing maximal oxidant production in the presence of both P-Rex1 and WT Rac1 (compared to P-Rex1 without exogenous Rac1, solid line). Co-transfection of Rac1 T17N ablated the fMLF-induced superoxide generation. (B) Quantification of data in (A), based on isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence in the first 20 min after fMLF stimulation. The expressed P-Rex1 and Rac1 constructs were detected with Western blotting using anti-AU5 (for the AU5-tagged P-Rex1) and anti-Myc (for the Myc-tagged WT and T17N mutant of Rac1). β-actin (untagged) was also detected by a monoclonal antibody against β-actin, and was used as a loading control. (C) fMLF-induced Rac1 activation based on RBD-GFP pull-down assay. The Rac1 recovered was then detected using an anti-Rac1 antibody in Western blotting. The upper bands in the blot (right four lanes) represent the Myc-tagged exogenous (exo) Rac1, and the lower bands are endogenous (endo) Rac1 in COSphox cells. Densitometric analysis was performed and relative level of Rac-GTP is shown after normalization against the respective endogenous and exogenous total Rac1. Data are shown as mean±SEM based on three independent experiments. * P<0.05. Panel (A) is shown in color in the online version.

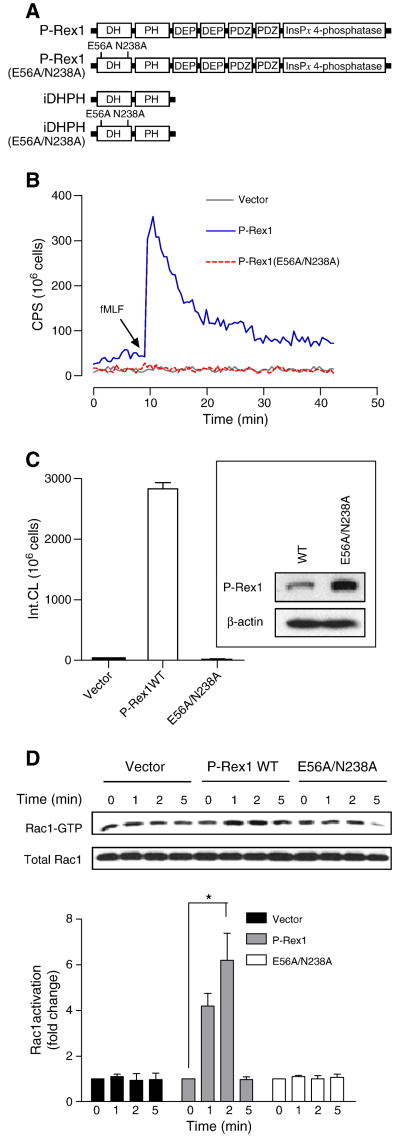

3.3. The E56A/N238A mutation abolishes P-Rex1-mediated reconstitution of NADPH oxidase

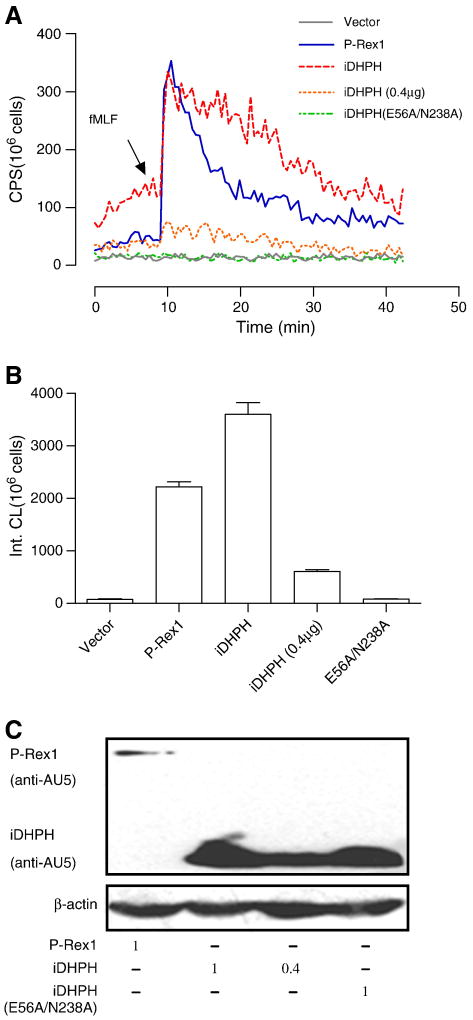

To study the activity of P-Rex1 in COSphox cells, we prepared P-Rex1 constructs with deletion and point mutations and AU5 tagging at their N-termini. These constructs consisted of a double-mutant (E56A/N238A) in the DH domain (GEF-dead mutant), an isolated DH-PH domain (iDHPH) and an iDHPH containing the E56A/N238A mutation (iDHPH(E56A/N238A); Figure 4A). All P-Rex1 proteins were expressed with the expected sizes (apparent mass of 185,000 for the WT and E56A/N238A mutant of P-Rex1, and 45,000 for the iDHPH and iDHPH(E56A/N238A) mutants). Compared to the full-length P-Rex1, the iDHPH mutants were expressed at a higher level in COSphox cells (Figure 5C).

Fig. 4.

Requirement of functional DH domain for P-Rex1-dependent reconstitution of superoxide production. (A) Schematic representation of the full-length P-Rex1 and its deletion and point mutants. (B) Absence of fMLF-induced superoxide generation in COSphox cells expressing the E56A/N238A double mutations that disrupt the function of the DH domain. (C) Quantification of data in (B). The inset shows expression of the full-length P-Rex1 and E56A/N238A double mutant in the transfected COSphox cells as determined with Western blotting. (D) the full-length P-Rex1, but not its E56A/N238A double mutant, mediates fMLF-induced Rac1 activation as determined in RBD-GST pull-down assay. Densitometric analysis was performed and relative level of the active Rac1 is shown as fold change compared to the vector-transfected, unstimulated sample, after normalization against the expression level of total Rac1. Data shown are mean±SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. * P<0.05. A color version of panel (B) is available online.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the isolated DH-PH domains to the full-length P-Rex1 in superoxide reconstitution assay. (A) Superoxide production in COSphox cells expressing the FPR and either the full-length P-Rex1 or its isolated DH-PH domains (iDHPH) or the double mutant at E56 and N238. Notice elevated baseline in cells expressing iDHPH at a DNA input of 1 μg (same amount used for full-length P-Rex1). With reduced DNA input (0.4 μg), superoxide generation is barely inducible by fMLF (dotted line in gray). (B) Quantification of the data in (A), without taking protein expression levels into consideration. (C) The level of expression for the various P-Rex1 constructs showing that iDHPH was expressed at much higher level than the full-length P-Rex1. The amount of DNA used in each experiment was shown below (in μg). All experiments were performed for at least 3 times, and representative data are shown. A colored version of panel (A) is available online.

In reconstituted COSphox cells expressing human FPR1 and one of the P-Rex1 constructs, P-Rex1(E56A/N238A) failed to mediate fMLF-induced superoxide generation (Figure 4B, 4C), indicating that a functional DH domain is essential for the guanine nucleotide exchange function leading to Rac activation, as reported previously [32]. This result is confirmed in the RBD pull-down assay, showing that P-Rex1(E56A/N238A) failed to mediate Rac1 activation in fMLF-stimulated, reconstituted COSphox cells (Figure 4D). In comparison, expression of the iDHPH mutant resulted in elevated superoxide production in unstimulated cells (Figure 5A). However, because iDHPH and its E56A/N238A mutant were expressed at higher levels than the full-length WT P-Rex1 (Figure 5C), they exhibited reduced capability of activating NADPH oxidase on a molar basis (Figure 5B). This is evident as lowering the input DNA concentration of iDHPH from 1 μg to 0.4 μg markedly decreased its ability to induce superoxide production (Figure 5A, 5B). It is predicted that structural determinants other than the DH-PH domains are required for optimal activity of P-Rex1 following fMLF stimulation.

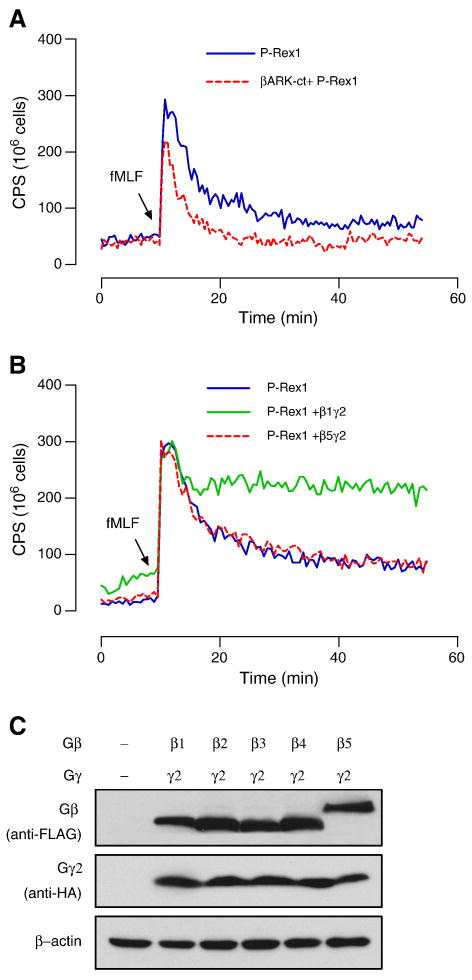

3.4. Gβγ proteins potentiate P-Rex1-mediated superoxide production

Since P-Rex1 was previously identified as a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and Gβγ-activated GEF, we examined the role of Gβγ proteins in the P-Rex1-dependent NADPH oxidase activation in reconstituted COSphox cells. Scavenging Gβγ with a C-terminal fragment of GRK2 (bARK) results in a ∼50% reduction in superoxide production over a period of 20 min (Figure 6A). Transfecting the COSphox cells with expression vectors coding for various Gβ subunits and a Gg2 subunit produced an overall enhancement in superoxide generation except with Gβ5, which had no effect (Figure 6B). Among the Gβ proteins, Gβ1 and Gβ2 were similarly potent while Gβ3 and Gβ4 were less (∼15%) potent in potentiating the fMLF-induced superoxide generation (representative tracing for Gβ1 and Gβ5 are shown, Figure 6B). All the transfected Gβ and Gβ2 proteins are properly expressed as shown in Western blotting (Figure 6C). These findings are consistent with the report that Gβ5 functions differently than other forms of Gβ [33], and provide an example of Gβγ signaling for P-Rex1 activation in a cell-based functional assay.

Fig. 6.

Effects of Gβγ expression on P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation. (A) Expression of the Gβγ scavenger, a C-terminal fragment of GRK2 (βARK-ct) that was co-transfected into the reconstituted COSphox cells, reduces P-Rex-1-dependent superoxide generation. In (B) and (C), individual expression plasmids coding for FLAG-tagged Gβ subunits (β1-β5) were co-transfected into P-Rex1 reconstituted COSphox cells together with an HA-tagged Gγ2 expression plasmid, and fMLF-induced superoxide generation was measured. Representative tracings show that expression of Gβ1γ2 potentiated superoxide generation, while Gβ5γ2 produced no effect. The relative expression level of each Gβ subunit and the Gγ2 subunit is shown in (C) using the anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies for Western blotting, respectively. A colored version of this figure is available online.

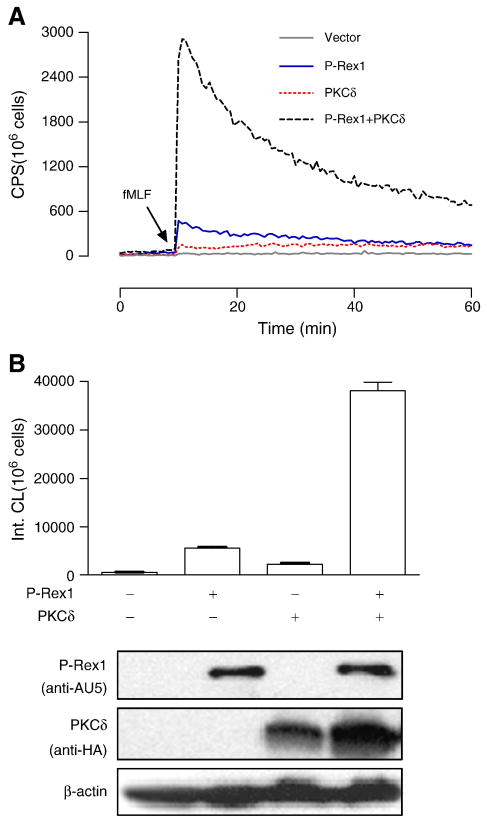

3.5. PKCδ potentiates P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation

PKC is a group of structurally related protein kinases that play important roles in cellular functions [34]. In neutrophils, members of the conventional PKC (α and βII), novel PKC (δ) and atypical PKC (ζ) families have been shown to mediate the phosphorylation of p47phox [35-38]. We recently reported that, in FPR-expression COSphox cells, reconstitution of fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase requires exogenous PKCδ and phosphorylation of its activation loop [18]. The finding suggests that PKCδ activation is one of the important mechanisms for fMLF-induced superoxide production in neutrophils. Since the expression of P-Rex1 is sufficient for fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation in FPR1-expressing COSphox cells (Figure 1), we speculated that fMLF activates multiple signaling mechanisms for superoxide production, and the presence of both PKCδ and P-Rex1 might lead to more potent NADPH oxidase activation. This possibility was examined by co-transfecting COSphox cells with P-Rex1, PKCδ or both. As shown in Figure 7, P-Rex1 and PKCδ produced a synergistic effect in NADPH oxidase activation, resulting in superoxide production 4.5-fold more than that produced in cells expression P-Rex1 or PKCδ individually (Figure 7B).

Fig. 7.

PKCδ potentiates P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation. The fMLF-induced superoxide generation was determined in COSphox cells expressing FPR together with Prex1, PKCδ or both. (A) Production of superoxide as determined using isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence in fMLF (1 μM) stimulated cells. (B) Quantification of superoxide produced in the first 20 min after fMLF stimulation, based on integrated chemiluminescence (Int. CL). The relative expression levels of the transfected constructs are shown below the bar graph. At least 3 experiments were performed, and similar results were obtained. Representative data are shown. A colored version of this figure is available online.

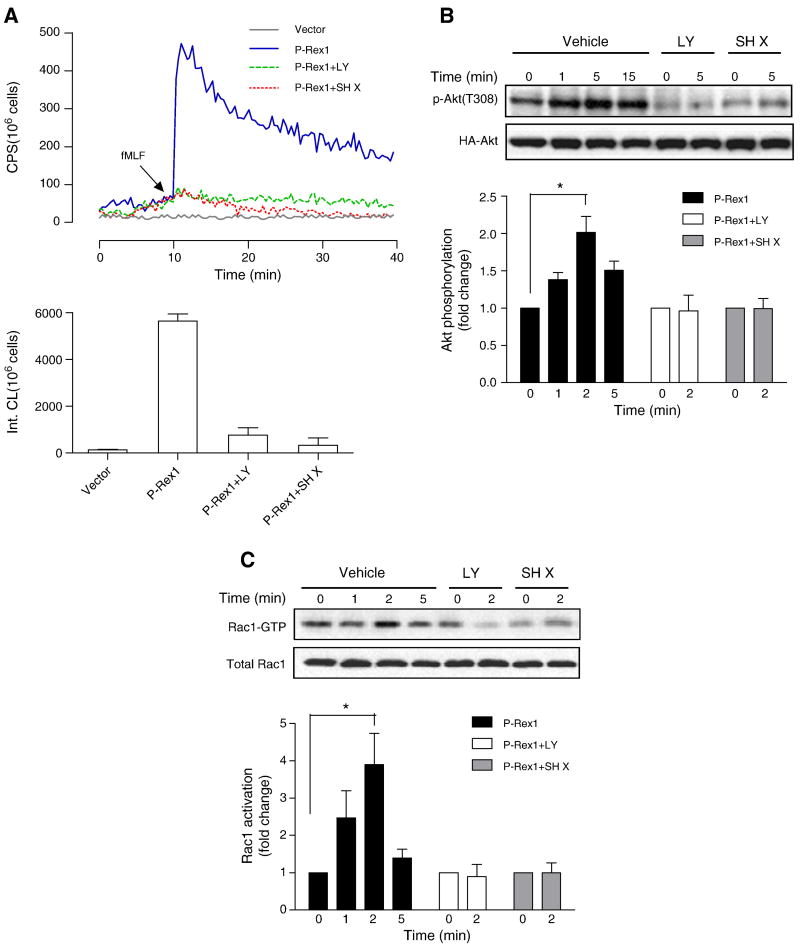

3.6. P-Rex1-mediated Rac activation is regulated by PI3K as well as Akt

P-Rex1 was initially identified as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor regulated by both Gβγ subunits and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [22]. In our reconstitution assays, we confirmed that pretreatment of the COSphox cells with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 diminished the fMLF-induced superoxide generation (Figure 8A). Surprisingly, the Akt inhibitor X (SH X) also produced significant inhibition of superoxide generation (Figure 8A). This finding raises the possibility that both PI3K and Akt regulate the activation of p-Rex1. As shown in Figure 8B and 8C, LY294002 and SH X inhibited the fMLF-induced Akt phosphorylation at Thr308. Moreover, the inhibitors also reduced Rac1 activation in fMLF-stimulated cells, suggesting a crosstalk between Akt and p-Rex1 activation of Rac1.

Fig. 8.

Regulation of P-Rex1-mediated superoxide generation and Rac1 activation by PI3K and Akt. Transfected COSphox cells expressing FPR and P-Rex1 were treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (50 μM) or the Akt inhibitor SH X (5 μM) for 5 min before fMLF (1 μM) stimulation. Quantification of the data was shown in bar graph below, based on integration of chemiluminescence in the first 20 min after fMLF stimulation. (B) The transfected COSphox cells were similarly treated with LY294002 or SH X as in (A), and fMLF-induced Akt phosphorylation was determined with an anti-pAkt (Thr308) Ab. Densitometric analysis was performed and relative phosphorylation of Akt was determined after normalization against total Akt in the same sample. Data shown are mean±SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. * P<0.05. (C) fMLF-induced Rac1 activation was determined using RBD-GST pull-down assay, in the transfected COSphox cells treated with either LY294002 or SH X treatment as in (A). Densitometric analysis was performed and relative level of activated Rac1 was determined after normalization against total Rac1 in the same samples. Data shown are mean±SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. * P<0.05. A colored version of panel (A) is available online.

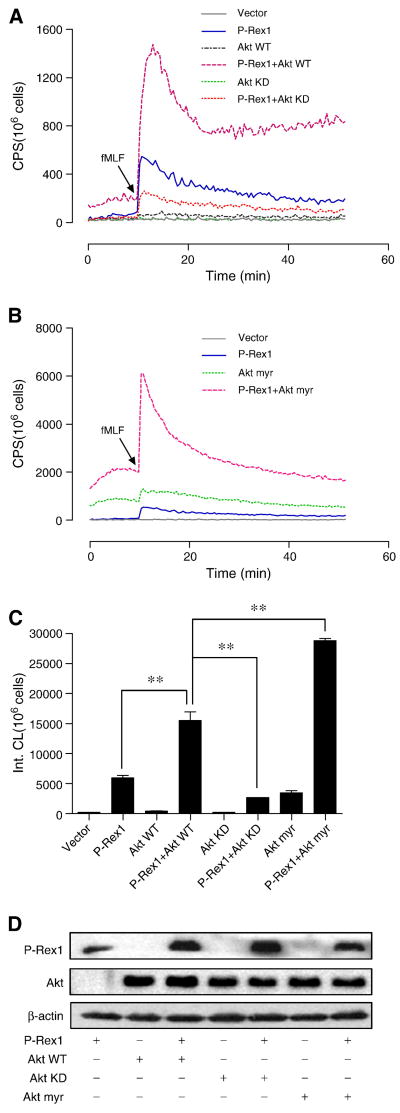

In order to confirm whether Akt is involved in the regulation of P-Rex1, we co-transfected COSphox cells with expression constructs coding for WT Akt, a kinase-dead Akt mutant (Akt KD), or a myristoylated form of Akt (Akt myr), together with a FPR1 expression construct and, in some samples, with a P-Rex1 expression construct. Expression of WT Akt did not alter the basal superoxide production (Figure 9A). Surprisingly, expression of WT Akt together with P-Rex1 produced a synergistic effect in superoxide production (Figure 9A, 9C). When WT Akt was replaced with Akt KD, superoxide production was significantly reduced. We also determine the effect of Aky myr in COSphox cells. Expression of the constitutively active Akt myr raised the basal level of superoxide production (Figure 9B; notice that Y axis scale is different from that of Figure 9A). Co-transfection of COSphox cells with Akt myr and P-Rex1 created a synergistic effect, increasing superoxide production above the level found in cells expressing P-Rex1 alone or P-Rex1 plus WT Akt (Figure 9B, 9C). All Akt constructs were expressed at similar levels as determined by Western blotting (Figure 9D).

Fig. 9.

Effects of Akt overexpression on P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation. COSphox cells were transfected to express FPR, together with P-Rex1, Akt1 (Akt WT), a kinase-dead mutant Akt1 (Akt KD), or a myristoylated Akt1 (Aky myr). (A) Comparison of Akt WT and Akt KD for the effect on P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation. (B) Effect of Akt myr alone and the combined effect of Akt myr and P-Rex1 in superoxide generation. Note a different Y-axis scale than in (A). (C) Quantification of superoxide generation in (A) and (B), based on integrated chemiluminescence produced in the first 20 min after fMLF stimulation. Data are mean ± SEM based on three independent experiments. ** P < 0.01. (D) Expression of P-Rex1 and the WT and mutant Akt in transfected COSphox cells, as determined with Western blotting using an anti-AU5 antibody for the AU5-tagged P-Rex1 and anti-HA antibody for the HA-tagged Akt. Representative data from one of the three experiments are shown. A part of this figure is shown in color in the online version.

3.7. Positive feedback between PI3K-Akt and Rac1

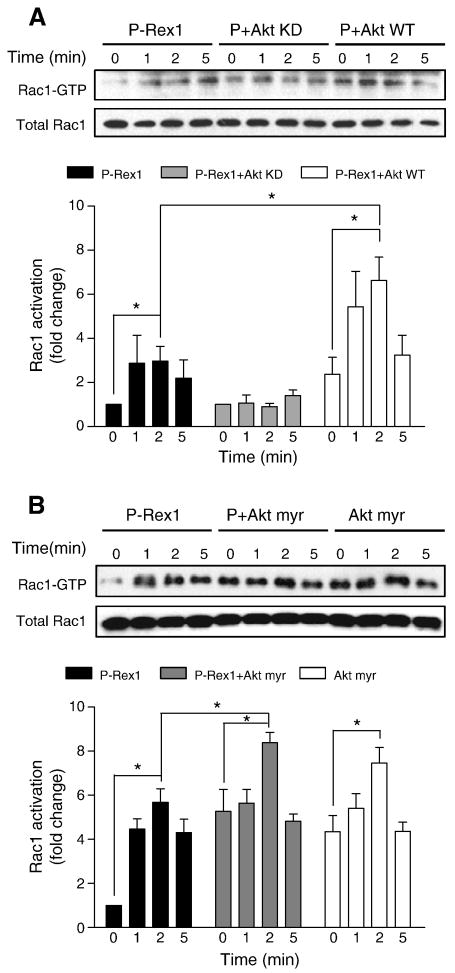

The results described in 3.6. suggest that the serine/threonine kinase Akt plays a role in P-Rex1-mediated superoxide generation. The mechanism by which Akt contributes to the activation of NADPH oxidase is incompletely understood. Hoyal et al and Chen et al reported that Akt phosphorylates p47phox at Ser304 and Ser328 [39, 40]. Phosphorylation of p47phox and activation of Rac are two important events in the activation of NADPH oxidase. We therefore determined whether Akt could affect Rac1 activation in FPR1-reconstituted COSphox cells. When expressed together with P-Rex1, WT Akt, but not Akt KD, potentiated fMLF-induced, P-Rex1-dependent Rac1 activation (Figure 10A). Expression of the constitutively active Akt myr construct raised the basal level of Rac1 activation independent of P-Rex1 (Figure 10B). An additional increase was observed when Akt myr was expressed together with P-Rex1. Therefore, Akt appears to regulate Rac1 activation in P-Rex1-dependent and -independent manners.

Fig. 10.

Effects of Akt overexpression on Rac1 activation. COSphox cells were transfected similarly as in Figure 9 to express FPR, and P-Rex1 together with Akt WT or Akt KD (A), or with Akt myr alone or in combination with P-Rex1 (B). After fMLF (1 μM) stimulation for the indicated time, Rac1 activation was determined in PBD-GST pull-down assay. Densitometric analysis was performed and relative level of activated Rac1 was determined after normalization against total Rac1 in the same sample. Data were represented as mean±SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

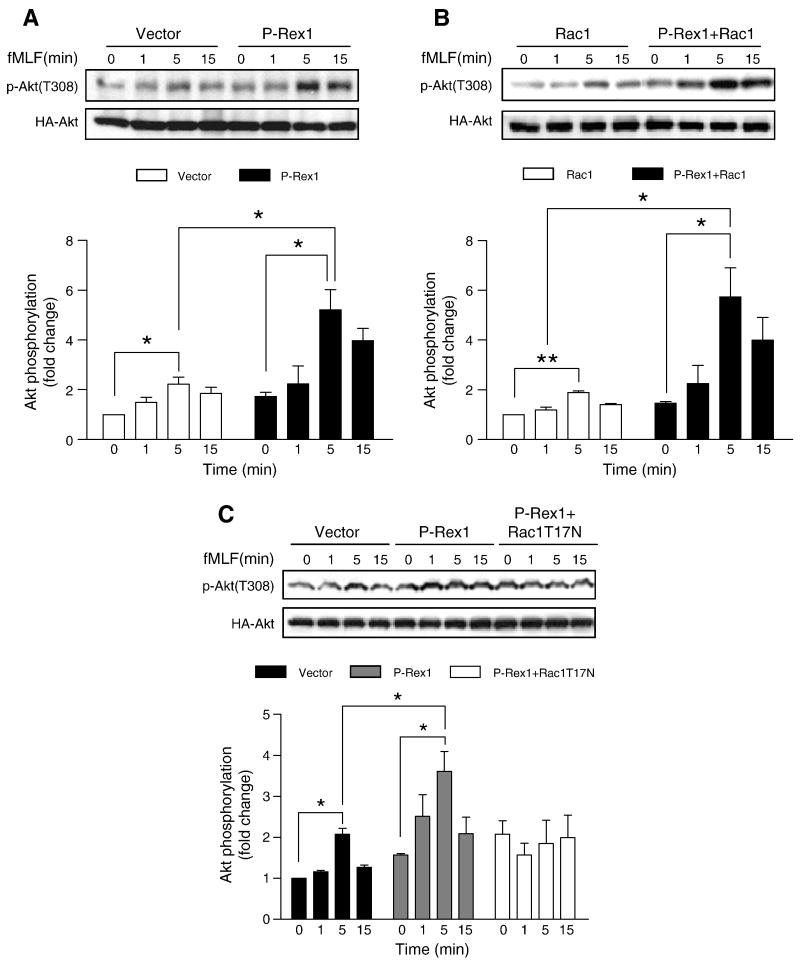

PI3K activation generates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 that in turn regulates the Rac-GEF activity of P-Rex1 [22]. It was reported that Rac could also stimulate the activation of PI3K, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear [41]. We speculated that P-Rex1 and Rac1 may regulate Akt activation, and examined this possibility in FPR1-reconstituted COSphox cells. Akt activation was determined on the basis of its phosphorylation at Thr308. As shown in Figure 11A, an increase in Akt phosphorylation was observed in COSphox cells expressing P-Rex1 as compared to the control cells expressing the empty vector. Overexpression of Rac1 and P-Rex1 enhances the fMLF-induced Akt phosphorylation (Figure 11B). In comparison, expression of a dominant negative form of Rac1 reduced the fMLF-induced Akt phosphorylation in cells expressing P-Rex1 (Figure 11C). Taken together, results from these experiments suggest a positive feedback loop between the PI3K/Akt pathway and the P-Rex1/Rac1 pathway, whereby Akt promotes P-Rex1-dependent Rac1 activation and Rac1, once activated, can in turn stimulate Akt phosphorylation.

Fig. 11.

Effects of P-Rex1 and Rac1 on Akt phosphorylation. COSphox cells were transfected with expression constructs coding for FPR, P-Rex1 and, in some samples, Rac1 WT or Rac1 T17N. A HA-tagged Akt1 WT construct was co-transfected in all samples. Phosphorylation of Akt1 was determined using an anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308) antibody, in fMLF (1 μM) stimulated cells expressing control (vector), P-Rex1 (A), P-Rex1 plus Rac1 (B), and P-Rex1 plus Rac1 T17N (C). Total HA-Akt1 in the same cell lysate was determined. The relative level of Akt phosphorylation was shown in bar graphs below each blot. Densitometric analysis was performed and relative phosphorylation of Akt was determined after normalization against the total Akt level in transfected cells. Data were represented as mean±SEM of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

P-Rex1 was originally purified from neutrophils as a Gβγ and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-regulated activator of Rac [22]. It was heralded as the long sought-after factor that specifically catalyzes the exchange of guanine nucleotide on Rac2 upon chemoattractant receptor activation [42, 43]. Subsequent biochemical characterization confirmed that P-Rex1 interacts with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and with Gβγ subunits [32, 44], and identified PKA phosphorylation as a potential regulatory mechanism for the activity of P-Rex1 [45]. However, neutrophils from P-Rex1 knockout mice are only partially defective in fMLF- and C5a-induced superoxide generation [20, 21], whereas genetic deletion of Vav1, another guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac, caused a marked reduction in fMLF-stimulated superoxide generation [19]. These observations raise the question of whether P-Rex1 is the predominant GEF for Rac activation in neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation. The presence of multiple signaling molecules, with possibly redundant functions, has made it difficult to study the individual molecules in neutrophils. We therefore took a different approach to investigate whether these GEFs are sufficient to reconstitute fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation in a transgenic cell line that lacks key molecules downstream of chemoattractant receptors. Our study demonstrates for the first time that heterologous expression of P-Rex1 is sufficient for the reconstitution of NADPH oxidase activity following fMLF stimulation in FPR1-expressing COSphox cells.

P-Rex1 is the first Rho GEF known to be activated synergistically by both Gβγ and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. In reconstitution assays, we confirmed that inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 abolishes the P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation, and co-expression of a βγ scavenger partially reduced the fMLF-stimulated supeorxide production. Gβγ has been reported to directly interact with P-Rex1 [32, 44] and promote P-Rex1 membrane translocation [46]. We found that in reconstitution assays overexpression of Gβ1γ2 markedly potentiated the fMLF-induced, P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation. Interestingly, the additional Gβ1γ2 expressed in the reconstituted COSphox cells produced a sustained superoxide generation compared to the transient response in cells expressing P-Rex1 alone. The change in the kinetics of superoxide generation suggests that the rapid and transient superoxide production typically seen in chemoattractant-stimulated cells may be the result of limited Gβγ availability, which can occur after inactivation of Gαi and association of the GDP-bound Gαi with Gβγ, a process accelerated by factors having GTPase activating protein activity such as the regulators of G protein signaling (RGS). In the current study, we tested different Gβ subunits in combination with the co-expressed Gγ subunit, and found that Gβ1γ2 and Gβ2γ2 produced similar enhancement in superoxide generation. Gβ3γ2, and especially Gβ4γ2, are less effective, while Gβ5γ2 has no effect, in P-Rex1-dependent superoxide generation when over-expressed in the reconstituted COSphox cells (data not shown). These results are consistent with previously reported in vitro characterization of Gβγ-mediated activation of P-Rex1 based on Rac binding of [35S]-GTPγS [33], and together indicate differential regulation of P-Rex1 by the Gβγ dimers.

P-Rex1 is structurally characterized with its N-terminal DH and PH domains, followed by tandem DEP and PDZ domains and a C-terminal inositol polyphosphate-4 phosphatase domain [22]. The inter-molecular interactions and functions of these domains remain incompletely understood. Published studies have shown that the isolated DH-PH domains can be activated by Gβγ and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and is able to translocate to membrane [32, 46]. It was also suggested that the DEP, PDZ and IP4P domains serve to keep P-Rex1 in the cytosol in unstimulated cells [46]. However, a more recent study indicates that the second DEP domain and first PDZ domain interact with the PI4P domain, and the domain-domain interaction is important to Gβγ binding [44]. In that model, the isolated DH-PH domain cannot directly interact with Gβγ subunits. In the current study, we compared the isolated DH-PH domains in NADPH oxidase reconstitution assay, and found that the iDHPH construct was able to mediate fMLF-induced superoxide generation only when expressed a higher levels. On a molar basis the iDHPH construct is much less effective than the full-length P-Rex1 in reconstituting the fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation. Therefore, the DEP, PDZ and PI4P domains appear to have additional functions for maximal NADPH oxidase activation, although further studies will be necessary to understand their respective functions.

In neutrophils, the Gβγ-activated class IB PI3K [47] has been reported to play an important role in chemoattractant-induced neutrophil activation, including superoxide generation [48-50]. Therefore, Gβγ subunits appear to regulate P-Rex1 through two distinct mechanisms: Gβγ directly interact with P-Rex1 and facilitate its membrane translocation [46], and Gβγ-mediated PI3Kγ activation leads to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production which in turn activates P-Rex1. We have shown in the current study that the Gβγ scavenger only partially blocked the fMLF-induced superoxide generation, whereas the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 completely abolished the fMLF-induced response, suggesting that PI3K activation is critical and may not be entirely Gβγ-dependent. Moreover, PI3Kγ, the Class IB PI3K, is absent from COS cells [17] and cannot contribute to P-Rex1 activation in our reconstitution assays. Taken together, these results suggest that the activation of Class IA PI3Ks is responsible for fMLF-induced PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production and P-Rex1 activation in COSphox cells. The role for Class IA PI3K in neutrophil activation has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Published studies have shown biphasic increase in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production, with the Class IB PI3K responsible for the first phase and Class IA PI3Ks contributing to the second phase [51, 52]. These studies, however, present conflicting data with regard to the requirement of Class IB PI3K for the second phase of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production. Our results demonstrate that P-Rex1 activation and superoxide generation do not require the Class IB PI3K in the reconstituted COSphox cells, suggesting that Class IA PI3Ks are primarily responsible for chemoattractant-induced superoxide generation in our assay conditions. It is likely that this class of PI3Ks also play important roles in neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation [52, 53].

Vav1 is one of the hematopoietic cell-specific Dbl family Rho GEFs that plays an important role in T cell signaling [54]. Vav1 activation requires phosphorylation of Tyr174 to remove inhibition of its DH domain [55], and deletion of the N-terminal 186 amino acids, including the caponin homology domain, results in a constitutively active Vav construct [56]. Activation of T cell receptors and Fcγ receptors results in the phosphorylation of Vav, and Vav1 and Vav3 have been shown to play a role in FcγR-mediated superoxide generation [57]. In knockout mice lacking Vav1, the fMLF-induced superoxide generation was significantly reduced [19], suggesting that Vav1 also contribute to neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation. However, in the current study, heterologous expression of Vav1 is unable to reconstitute fMLF-induced NADPH oxidase activation in COSphox cells. We have observed that expression of a deletion mutant of Vav1 lacking the N-terminal 186 amino acids [27] led to constitutive production of superoxide (data not shown). This result is consistent with a previous report demonstrating that expression of constitutively active Vav2 or Tiam1 potently activates NADPH oxidase in COSphox cells [16]. Together, these observations demonstrate that Vav1, when activated, is able to catalyze guanine nucleotide exchange in COSphox cells; but the COSphox cells may not contain the endogenous tyrosine kinases necessary for fMLF-induced Vav activation. Recent studies have shown that the Src family kinases Hck and Fgr are involved in fMLF-induced neutrophil activation [58]. It will be interesting to determine whether heterologous expression of these kinases in COSphox will enable Vav1 activation. Since NADPH oxidase activation may be reconstituted in COSphox cells by co-expression of FcγRIIA and p40phox [59], it is possible that another Rho GEF is able to catalyze the FcγR-mediated Rac1 activation in these cells.

Finally, a previously unidentified and potentially important function of Akt in the regulation of fMLF-induced superoxide production was suggested by the data from this study. Akt is a downstream effector of PI3K, and its activation requires PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. It has been reported that Akt is one of the several serine and threonine kinases that phosphorylate p47phox [39, 40]. We have found a positive feedback regulation of Akt and Rac, in which Rac activation is facilitated in the presence of myristoylated Akt as well as overexpressed WT Akt. Likewise, Akt phosphorylation, which reflects its activation, is potentiated by Rac1 and P-Rex1 in the reconstituted COSphox cells. These findings indicate that, in addition to its role in phosphorylating p47phox, Akt can phosphorylate another substrate which in turn lead to Rac activation. Although the target and detailed mechanisms remain unclear at this time, there is no doubt that further investigation will lead to the identification of potentially new pathways and molecules that mediate Rac-dependent phosphorylation of Akt as well as an Akt substrate that plays a role in Rac activation.

5. Conclusion

This study investigates the physiological functions and signaling properties of P-Rex1 in a reconstituted cell model that mimics neutrophils in superoxide generation and overcomes the difficulty in genetic manipulation using neutrophils. The results demonstrate that P-Rex1, but not Vav1, is critical to superoxide generation through G protein-coupled receptors in the transfected COSphox cells. In addition to activating the Rac small GTPase, there is crosstalk of the p-Rex1-Rac pathway and the serine/threonine kinase Akt. Together these signaling events lead to superoxide generation.

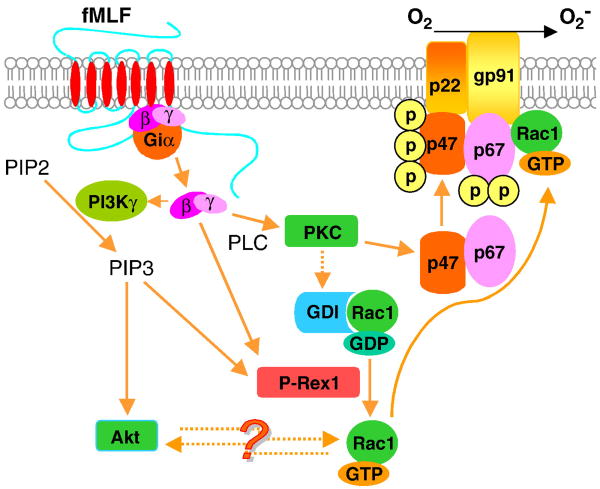

Fig. 12.

Schematic drawing depicting the role of P-Rex1 in fMLF-stimulted superoxide generation in FPR1-expressing COSphox cells. Solid lines indicate the signaling pathways characterized in neutrophils. Dashed lines represent signaling pathways suggested but not fully investigated in neutrophils. The question mark indicates possible presence of another protein(s) in the reciprocal regulation of Akt and Rac1 in COSphox cells. Several known signaling molecules, e.g., PAK1 for its role in the feed forward mechanism, are not shown due to space limitation. Also not shown are membrane localization of PIP3 and the translocation process of activated Akt, P-Rex1 and PKC. This figure is shown in color in the online version.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Dianqing Wu for providing the P-Rex1 gene for heterologous expression and Dr. Ming Wenyu for the GFP-Vav1 construct. We also thank our laboratory members for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Heal grant P01 HL077806 and R01 AI033503 (to R.D.Y).

Abbreviation

- P-Rex1

Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1

- fMLF

fMet-Leu-Phe

- CGD

chronic granulomatous disease

- FPR1

formyl peptide receptor 1

- GEF

guanine nucleotides exchange factors

- PIP3

phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- PAK1

p21-activated kinase 1

- RBD

Rac-binding domain

- RGS

regulators of G protein signaling

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Babior BM. Blood. 1999;93(5):1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLeo FR, Quinn MT. J Leuk Biol. 1996;60(6):677–691. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauseef WM. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122(4):277–291. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0679-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinauer MC, Orkin SH. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:117–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyworth PG, Cross AR, Curnutte JT. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15(5):578–584. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson SH, Gallin JI, Holland SM. J Exp Med. 1995;182(3):751–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollock JD, Williams DA, Gifford MA, Li LL, Du X, Fisherman J, Orkin SH, Doerschuk CM, Dinauer MC. Nat Genet. 1995;9(2):202–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts AW, Kim C, Zhen L, Lowe JB, Kapur R, Petryniak B, Spaetti A, Pollock JD, Borneo JB, Bradford GB, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC, Williams DA. Immunity. 1999;10(2):183–196. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyneman RA, Vercauteren RE. J Leukoc Biol. 1984;36(6):751–759. doi: 10.1002/jlb.36.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bromberg Y, Pick E. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(25):13539–13545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curnutte JT. J Clin Invest. 1985;75(5):1740–1743. doi: 10.1172/JCI111885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPhail LC, Shirley PS, Clayton CC, Snyderman R. J Clin Invest. 1985;75(5):1735–1739. doi: 10.1172/JCI111884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman JL, Lambeth JD. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(37):22578–22582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Mendez I, Leto TL. Blood. 1995;85(4):1104–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown GE, Stewart MQ, Liu H, Ha VL, Yaffe MB. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):35–47. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price MO, McPhail LC, Lambeth JD, Han CH, Knaus UG, Dinauer MC. Blood. 2002;99(8):2653–2661. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He R, Nanamori M, Sang H, Yin H, Dinauer MC, Ye RD. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7462–7470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng N, He R, Tian J, Dinauer MC, Ye RD. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7720–7728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim C, Marchal CC, Penninger J, Dinauer MC. J Immunol. 2003;171(8):4425–4430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch HC, Condliffe AM, Milne LJ, Ferguson GJ, Hill K, Webb LM, Okkenhaug K, Coadwell WJ, Andrews SR, Thelen M, Jones GE, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. Curr Biol. 2005;15(20):1867–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong X, Mo Z, Bokoch G, Guo C, Li Z, Wu D. Curr Biol. 2005;15(20):1874–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch HC, Coadwell WJ, Ellson CD, Ferguson GJ, Andrews SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. Cell. 2002;108(6):809–821. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao T, Nalbant P, Hoshino M, Dong X, Wu D, Bokoch GM. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(4):1127–1136. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ming W, Li S, Billadeau DD, Quilliam LA, Dinauer MC. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(1):312–323. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00985-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benard V, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(19):13198–13204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. J Immunol Methods. 1999;232(1-2):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price MO, Atkinson SJ, Knaus UG, Dinauer MC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):19220–19228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akasaki T, Koga H, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):18055–18059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geijsen N, van Delft S, Raaijmakers JA, Lammers JW, Collard JG, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Blood. 1999;94(3):1121–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abo A, Pick E, Hall A, Totty N, Teahan CG, Segal AW. Nature. 1991;353(6345):668–670. doi: 10.1038/353668a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knaus UG, Heyworth PG, Evans T, Curnutte JT, Bokoch GM. Science. 1991;254(5037):1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.1660188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill K, Krugmann S, Andrews SR, Coadwell WJ, Finan P, Welch HC, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4166–4173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayeenuddin LH, McIntire WE, Garrison JC. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(4):1913–1920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishizuka Y. Science. 1992;258(5082):607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majumdar S, Kane LH, Rossi MW, Volpp BD, Nauseef WM, Korchak HM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1176(3):276–286. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90056-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kent JD, Sergeant S, Burns DJ, McPhail LC. J Immunol. 1996;157(10):4641–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nixon JB, McPhail LC. J Immunol. 1999;163(8):4574–4582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fontayne A, Dang PM, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, El-Benna J. Biochemistry. 2002;41(24):7743–7750. doi: 10.1021/bi011953s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoyal CR, Gutierrez A, Young BM, Catz SD, Lin JH, Tsichlis PN, Babior BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(9):5130–5135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031526100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Q, Powell DW, Rane MJ, Singh S, Butt W, Klein JB, McLeish KR. J Immunol. 2003;170(10):5302–5308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welch HC, Coadwell WJ, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiner OD. Curr Biol. 2002;12(12):R429–431. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00917-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dinauer MC. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10(1):8–15. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urano D, Nakata A, Mizuno N, Tago K, Itoh H. Cell Signal. 2008;20(8):1545–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayeenuddin LH, Garrison JC. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(4):1921–1928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barber MA, Donald S, Thelen S, Anderson KE, Thelen M, Welch HC. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(41):29967–29976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrews S, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(407):cm3. doi: 10.1126/stke.4072007cm3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z, Jiang H, Xie W, Zhang Z, Smrcka AV, Wu D. Science. 2000;287(5455):1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP. Science. 2000;287(5455):1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Stanford WL, Bolon B, Wakeham A, Itie A, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, Joza N, Mak TW, Ohashi PS, Suzuki A, Penninger JM. Science. 2000;287(5455):1040–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Condliffe AM, Davidson K, Anderson KE, Ellson CD, Crabbe T, Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B, Turner M, Webb L, Wymann MP, Hirsch E, Ruckle T, Camps M, Rommel C, Jackson SP, Chilvers ER, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. Blood. 2005;106(4):1432–1440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boulven I, Levasseur S, Marois S, Pare G, Rollet-Labelle E, Naccache PH. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7621–7627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao XP, Zhu X, Fu J, Liu Q, Frey RS, Malik AB. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6116–6125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tybulewicz VL. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17(3):267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aghazadeh B, Lowry WE, Huang XY, Rosen MK. Cell. 2000;102(5):625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schuebel KE, Movilla N, Rosa JL, Bustelo XR. Embo J. 1998;17(22):6608–6621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Utomo A, Cullere X, Glogauer M, Swat W, Mayadas TN. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6388–6397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fumagalli L, Zhang H, Baruzzi A, Lowell CA, Berton G. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3874–3885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suh CI, Stull ND, Li XJ, Tian W, Price MO, Grinstein S, Yaffe MB, Atkinson S, Dinauer MC. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1915–1925. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]