Abstract

Objectives

The Ho Chi Minh Youth cohort study aimed to assess the change in nutritional status; indicators of adiposity; diet; physical activity and sedentary behaviours; home, neighbourhood and school microenvironments and their complex relationships in adolescents in urban areas of Ho Chi Minh City.

Design

Prospective 5-year cohort.

Setting

Systematic random sampling was used to select 18 schools in urban districts.

Participants

Children were followed up over 5 years with an assessment in each year. Consent, from both adolescents and their parents, was required. At baseline, 759 students were recruited into the cohort, and of these students, 740 remained in the cohort for the first round, 712 for the second round, 630 for the third round and 585 for the last round of follow-up.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Anthropometric measurements were taken using established guidelines. Six main groups of exposure factors including dietary intake and behaviours, physical activity and sedentary behaviours, family social and physical environment, school environment, socioeconomic status and parental characteristics were measured.

Results

Retention rate was high (77%). Within 5-year period, the prevalence of combined overweight and obesity using International Obesity Task Force cut-off values increased from 14.2% to 21.8%. Time spent on physical activity decreased significantly in the 5-year period from 87 to 50 min/day. Time spent on sedentary behaviours increased in the 5-year period from 512 to 600 min/day.

Conclusions

The complete data analysis of this cohort study will allow a full exploration of the role of environmental and lifestyle behaviours on adolescent overweight and obesity and also identify the factors most strongly associated with excess weight gain and the appearance of overweight and obesity in different age groups of adolescents from this large city in Vietnam.

Article summary

Article focus

The change in nutritional status; indicators of adiposity; diet; physical activity and sedentary behaviours; home, neighbourhood and school microenvironments and their complex relationships in adolescents in urban areas of Ho Chi Minh city.

Key messages

Prevalence of combined overweight/obesity increased from 14.2% to 21.8% in 5-year period.

Time spent on physical activity decreased significantly in the 5-year period from 87 to 50 min/day.

Time spent on sedentary behaviours increased in the 5-year period from 512 to 600 min/day.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first cohort in Vietnam on adolescent obesity.

This study assessed a full set of potential risk factors from dietary intake, physical activity and sedentary behaviours to environmental factors, allowing a wide ranging assessment of the factors related to excess weight gain and overweight and obesity among urban Vietnamese adolescents.

The present longitudinal study revealed changes in anthropometric measurements, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and diet associated with age in both genders.

Introduction

In recent years, the increasing prevalence of obesity has become one of the major health concerns in children and adolescents in developed countries and in developing countries where an economic transition is underway.1 Vietnam and especially Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC)—the largest city in Vietnam—is in an early ‘nutrition transition’ where both undernutrition and the emerging problem of overweight and obesity can be found.2 Evidence of this transition can be found in the results of two cross-sectional nutrition surveys, which reported an increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity of adolescents in HCMC from 5.8% in 2002 to 13.7% in 2004 and over the same period a decline in the prevalence of underweight from 11.3% to 6.6%.3

It is known that adolescent obesity is associated with a range of potential medical and psychosocial complications, as well as being a risk factor for increased morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood.4 The intermediate consequences include the development of cardiovascular risk factors and persistence of obesity into adulthood. Reviews of the evidence suggest that the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality are elevated among adults who were overweight during childhood.5 However, evidence on risk factors for childhood obesity is limited at present, especially for transitional societies, and most previous studies on risk factors for obesity have been unable to adequately account for confounding variables, particularly socioeconomic status.6 Although both genetic and environmental factors are thought to cause obesity, awareness is increasing for the importance of environmental factors,7 including school, neighbourhood and home microenvironments, which play an influential role in determining unhealthy lifestyle choices.8

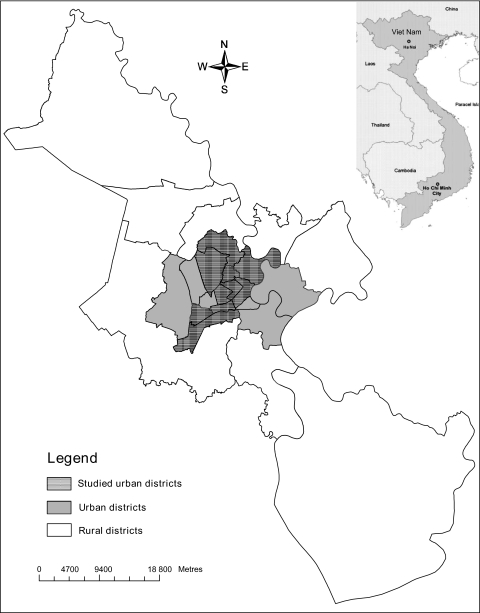

HCMC with a population of 7 million is one of the largest cities in Vietnam9 and is located in the south-east region of the country (figure 1). Over the last 2 decades, the city has experienced rapid social, economic and demographic changes. Parallel to these social and economic changes, overweight and obesity have emerged as among the most significant public health issues in the city. The examination of risk factors in a setting where such rapid changes are taking place provides a unique opportunity to obtain a picture of how overweight and obesity emerges in children in a population undergoing social and economic transition. The urban area of HCMC, with its high population density of 3155 persons/km2 and its rapid socioeconomic development, is an ideal setting to identify risk factors for excess weight gain in adolescents because of the ease of tracking and following up students.

Figure 1.

Map of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, with studied districts.

The present cohort study aimed to assess the change in nutritional status, indicators of adiposity, diet and physical activity and sedentary behaviours; home, neighbourhood and school microenvironments and their complex relationships in adolescents in urban areas of the province. The results of this study will provide new insights into how the childhood obesity epidemic in a transitional society differs from that in developed countries. It will also provide evidence to plan and evaluate the most appropriate interventions to prevent excess weight gain in adolescents in HCMC in the future.

Methods and analysis

Study design

Sample selection

The cohort study began from a multistage cluster cross-sectional survey in 2004. This survey covered 136 public junior high schools and four non-public (semi-public and private) junior high schools. Of these 140 schools, 47 were from wealthy urban areas and 93 from less wealthy urban districts. This classification of urban districts was derived from the Statistics Review of HCMC province Department of Statistics.10

Non-wealthy districts were categorised as having more than 50% households below the wealthy threshold (non-wealthy household). Non-wealthy household in HCMC in 2004 was identified as having average personal income <6.000.000 Vietnam Dong/person/year.11

The total number of students in wealthy urban schools was 62 853, while that of less wealthy urban schools was 119 717. From these 140 schools, 31 clusters (schools) were selected with 17 clusters (schools) selected from the list of schools in wealthy urban districts and 14 clusters (schools) from less wealthy urban districts, using probability proportionate to size sampling within each strata. Because the number of classes and students in non-public schools are smaller than in public schools, only three non-public schools were selected in the sample of the cross-sectional survey. In each selected school, lists of classes from grades 6 and 7 combined and grades 8 and 9 combined were prepared. Simple random sampling was used to select one class from each group of grades. All students in the selected classes were invited to participate in the study.

For the cohort study, systematic random sampling was used to select 18 schools from these 31 schools, of which 11 were from wealthy districts and seven were from less wealthy districts. The subsample of children required for the cohort study was selected from one class from grades 6 and 7 combined in each school, resulting in 784 students of the cohort study.

Sample size

The sample size estimates for the cohort study were based on expected differences in the average change of body mass index (BMI) between exposure groups (insufficiently active vs active students viewing >20 h TV per week vs <20 TV viewing per week, students in the lowest quintile of nutrient intake vs other quintiles of intake, students who ride bicycles to school vs were taken to school by motorcycle), using a SD of 1.5 and assuming a 5% significance level, 80% power. In the absence of information about relative change in BMI for HCMC children, these sample size estimates are based on the observed relative change in BMI in children exposed to an education intervention to reduce TV viewing in the USA.12 The average change in BMI selected was 0.35 kg/m2. Sample size estimates were calculated using the PS program,13 resulting in an estimated required sample size of 720 children. However, since we used cluster sampling (school and class selection), all the students in a selected class were invited to participate in the cohort for logistic reasons, yielding 784 students who were invited to participate and giving 759 who were recruited into the cohort study.

Informed consent

Informed written consent was first obtained from the principals of the schools participating in the study. Information about the study was distributed to the selected class by the school principals and class teachers using flyers and notices. All the students in selected classes were invited to participate in the cohort study. Discussions were held with the school principals to establish a timetable of visits to ensure project staff could meet all the children and parents. Information sheets and consent forms for the adolescents and their parents were distributed by the project staff at their first visit to the class. Project staff was also available to answer questions regarding the study on this visit. Consent from both the adolescents and their parents was required for participation in the study and collected 1 week apart.

Frequency of follow-up

Children were followed up over 5 years with an assessment in each year. During the first 3 years when the study participants were in junior high schools, data were collected by class surveys. In Vietnam, junior and senior high schools are separate institutions and students from one junior high school may move to many different senior high schools. So, when the study participants moved to senior high school, follow-up was sustained with individual contact by phone calls, home visits and group surveys for those students still together in a single high school.

Data collection

At each assessment round, we measured the main outcome variables (anthropometric measurements) as well as the exposure factors. In the third round, we collected biochemical data for assessing cardiovascular and metabolic disease risks.

Measurement of outcome variables

All the anthropometric measurements were taken using established guidelines.14 Standing height was measured using a portable direct-reading stadiometer, and body weight was measured using a digital scale. Waist and hip circumferences were measured with a non-elastic tape at the level of the umbilicus and with maximal extension of the buttocks. Standardisation exercises with the anthropometrists were used every 6 months to monitor the quality of anthropometric measurements. Blood samples (done in the third round) and blood pressure were measured at the end of data collection. Height, weight and blood pressure were measured twice and the average value was used.

Biochemical measurements

A sample of 5 ml of venous blood was collected from the participants' forearm by experienced trained technicians. Fasting blood glucose and the lipid profile (triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-, low- and very low-density cholesterol) were assayed by a photometer (Hitachi 917, Roche Diagnostics, Germany) using a standard method at the Diagnostic Center in HCMC.

Standard internationally recommended procedures were used for the handling and processing of blood specimens,15 and the specimens were transported to the laboratory within 2 h of collection at the schools. Serum samples were stored in special plastic tubes with sealed lids. Unused portions of the blood samples collected were stored at −20° in freezers in the laboratories of the Diagnostic Center, HCMC, in case reanalysis was needed once the data were examined. These specimens were destroyed once all the data have been cleaned.

Measurement of exposure factors

The adolescents were interviewed using the environmental assessment, food frequency, physical activity and television and computer usage questionnaires. The parents completed the family habits and environment questionnaire. Six main groups of exposure factors were measured:

Dietary intake and diet behaviours were assessed using a validated Youth Food Frequency Questionnaire,16 which allowed the study participants to be ranked by levels of food energy and fat intake and categories of different diet patterns, for example, frequency of fast food, snacks or soft drink consumption.

Physical activity and sedentary behaviours were assessed by the Adolescent Physical Activity Recall Questionnaire,17 which was developed and validated among Australian adolescents but modified for use in Vietnam, the Vietnamese-Adolescent Physical Activity Recall Questionnaire (V-APARQ) and an Adolescent Sedentary Activity Questionnaire.18 A validation study comparing the results from the V-APARQ with accelerometer measurements showed that V-APARQ is a valuable tool to assess physical activity in adolescents of HCMC.19 They were also objectively measured by use of accelerometers (Actigraph®) for each student over a 1-week period to assess long-term physical activity patterns.20

The family social environment was assessed using the family habits and environment questionnaire, which measured exposure to various social and physical home environmental factors (eg, number and location of TVs at home and family rules on TV viewing). Questionnaires were completed by the adolescents and their parents to assess exposure to environmental elements at home, school and neighbourhoods. The environmental questionnaire was developed from the results of group discussions with approximately 10–15 community members in each of four different locations of varying socioeconomic status from across HCMC. These group discussions identified the key environmental elements of homes, schools and neighbourhoods that needed to be included in the questionnaire. Lack of pathways and dangerous traffic were among the reasons many parents did not allow their children to walk or cycle alone. In-depth interviews were also conducted with selected members to explore in more detail the environmental risks identified and the opportunities for change. Interviews were taped, transcribed, checked for accuracy, and the content and themes were analysed to identify how the environmental risks varied across communities, how easily they might be modified and what methods of change were available in the different communities. The items on the questionnaire were derived from the information gathered from the qualitative data collection.21

Physical environment assessments were also taken using a questionnaire. The home environment questionnaire was piloted in a sample of 50 respondents (adolescents and their parents from different areas in HCMC) and validated by direct observations by the investigators. Information regarding environmental factors at community and household levels as well as socio-demographic factors was obtained via a self-administered questionnaire for parents. The description of this questionnaire has also been published previously.22

Distance between the respondent's house and schools and these recreational facilities were measured using Global Positioning System (GPS). GPS readings recorded the location of fast food outlets and recreation areas within 1 km surrounding the home of all participants in the cohort study. These data sources will be used to directly estimate the average distances from the respondent's home to these physical aspects of their environments and also to estimate the average density of these environmental elements.

School environment was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire completed by the school principals, who were asked about school facilities for sport and exercise, availability of such facilities and the foods and drinks sold in the school canteen.

Additional risk factors including self-recorded parent's weight and height, parental ethnicity and demographic and socioeconomic status of the child and the family were assessed by structured questionnaires.

To assess economic status, ownership of an inventory of assets was used to construct a household wealth index using the principal components method to assign a weight for each asset.23 A total of 14 assets were assessed including bicycles, motorbikes, televisions, radios, videos, cassette players, computers, gas stoves, CD players, cars, microwave ovens, refrigerator and telephone and air conditioners. The basis for selecting the assets was from a report of the Bureau of Statistics of HCMC10 listing the most common assets used among HCMC population.

Also the adolescent's pubertal status was self-assessed using a form, which recorded the child's date of birth, gender, weight and height, and questions to self-assessed pubertal status. In a confidential setting, the adolescents self-reported their pubertal status using a questionnaire with photographs illustrating five stages24 of pubertal development for pubic hair, male genitalia or female breasts and for female students, the date of their first menstruation was also recorded.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using STATA V.11 (STATA Corporation, 2009). The International Obesity Task Force BMI cut-off values were used to define overweight and obesity combined.25 The wealth index was ranked and divided into tertiles and each household was assigned to one of these wealth index categories.

The general characteristics of the population were described. For continuous variables, means and SDs or medians and IQRs were calculated according to the distribution of each variable. In the case of categorical variables, absolute and relative frequencies were calculated. The 95% CIs were also computed. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed were evaluated by the application of transformations and categorisations wherever applicable. Baseline characteristics were compared by gender, and the lost to follow-up group was compared with the cohort baseline group using Pearson χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical data, whereas continuous data were tested with Student t test or Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U test. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare medians of time spent on moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviours, and χ2 for trend was used to compare prevalence of BMI status by years. The ‘survey commands’ were used to account for the multistage cluster sampling design. Future analyses of this cohort data that assess relationships between exposure factors and the change of BMI, physical activity and sedentary behaviours will require mixed multiple regression models to adjust for the multistage cluster sampling and repeated measurements in individual study participants.

Ethics and dissemination

The research proposal was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, HCMC. It was also approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Newcastle (ethics reference: H-879-0904). Informed written consent was obtained from the principals of the schools participating in the study. Consent from both the adolescents and their parents was required prior to their participation in the study.

Results

At baseline, 759 of 784 students (selected from the cross-sectional study) consented to take part in the cohort study, of which 740 participated in the first follow-up data collection including anthropometric measurements, dietary, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and environment assessment. Therefore, the attrition rate for 1-year follow-up was 2.5%. In the second round of follow-up, there were 712 students (94% of baseline), in the fourth round, there were 630 students (83% of baseline) and in the last follow-up, 585 students remained in the cohort, resulting in a retention rate of 77% (online table 1).

The characteristics of the follow-up group (n=585) were compared with dropsout (n=174) on key variables that were available for all participants. These two groups did not differ by age, gender, pubertal status and anthropometric or socio-demographic characteristics. The dropouts in the sample were mainly attributed to the following reasons: (1) moved to another school (n=93, 12.2%); (2) refused to continue in the study (n=45, 5.9%) and (3) changed home address or migrated overseas (n=36, 4.7%).

The baseline data for socio-demographic and anthropometric variables are listed in online table 2. At baseline, the mean age of the sampled subjects was 11.8 years (±0.6). Overall, 12.5% of the students were overweight and 1.7% were obese. The mothers of 52.3% of the students had completed senior high school and 58.5% of the fathers had completed senior high school.

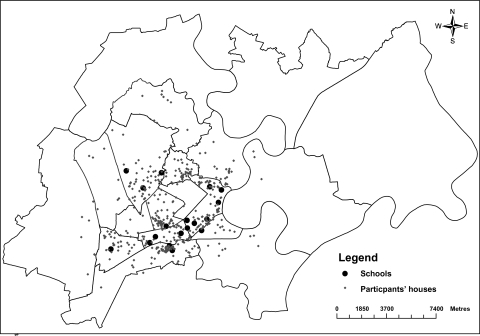

Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of schools and participants' home measured by GPS. Students' houses were scattered around their schools with a median distance from home to school of 1450 m (IQR: 680–3030 m).

Figure 2.

Map of studied schools and student participants' homes.

A summary of the changes in the BMI status and time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviours are listed in online table 3. Over the 5-year period of this cohort study, the prevalence of overweight increased from 12.5% to 16.7% and obesity from 1.7% to 5.1%. Time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity decreased significantly from 87 to 50 min/day. In contrast, time in sedentary behaviours increased from 512 to 600 min/day.

Previous papers based on the cross-sectional baseline survey have described overweight and obesity,3 26 physical inactivity22 and metabolic syndrome27 and associated risk factors. Another paper has used the longitudinal data from the youth cohort to describe changes in active commuting to school and risk factors for changes in commuting status.28 More results will be presented in future papers presenting changes in physical activity, sedentary behaviour and overweight/obesity and their associated risks factors.

Discussion

We have successfully implemented a 5-year follow-up study in adolescents in Vietnam with a high retention rate of 77%. Over this period, we found that the prevalence of combined overweight and obesity increased significantly from 14.2% to 21.8%. Self-reported time spent on physical activity decreased significantly from 87 to 50 min/day and in contrast, sedentary time increased from 512 to 600 min/day. This is the first cohort study on adolescent obesity in Vietnam, which provides a comprehensive assessment of the change in anthropometric growth, dietary intake, physical activity and environmental factors as well as their associations over the years of follow-up.

An important strength of the study was maintaining more than 75% of the students in this cohort, which has helped to ensure the internal validity of the study. Also, the measurements of key outcomes and study factors have high reliability and validity from the use of validated tools (FFQ, V-APARQ, environmental questionnaires) and objective measurements (accelerometers, GPS devices). The project staff, who took the measurements, was retrained throughout the study thus helping to ensure standard measurement methods were used across the cohort. We used a prospective longitudinal design from a representative sample of adolescents from HCMC and aimed to follow-up the children over 5 years. Each child has a health profile including anthropometric and pubertal status data as well as other exposure factors each year. The findings will be of relevance to other cities in Vietnam, which are starting to go through the same environmental and lifestyle changes that have already occurred in HCMC. The findings will also be relevant to other urban populations in East Asia and Southeast Asia where rapid economic development is leading to a nutrition transition similar to that occurring in HCMC.

The relatively small sample size is one limitation of the study restricting examination of all potential relationships because of the limited sample in some subgroups. However, the sample size was adequate to detect changes in BMI over time and changes in key study factors such as physical activity and screen time, which was used as a proxy for sedentary time. Despite this restriction, this study remains important because it is one of very few longitudinal studies in Vietnam and Southeast Asia to explore obesity and changes in obesity-related risk factors in adolescents.

Although there was only one non-public school in this study, this reflected the small proportion of the school population enrolled in this type of school in HCMC. We found no important differences between public and private schools for the main study factors and outcomes, such as socioeconomic status. Unlike the situation in many developed countries, in Vietnam, non-public schools are not popular and students usually enter these schools when they cannot secure a place in a public school. Thus, we believe that the sampling of this study was not biased and is representative of HCMC adolescents at school.

In HCMC, over the 5-year period, the prevalence of overweight increased from 12.5% to 16.7% and obesity increased from 1.7% to 5.1%. This increase in overweight and obesity was consistent with the increases found in 5-year follow-up studies from 1999 to 2004 in urban Indonesian children where the prevalence of overweight increased from 4.2% in children to 8.8% in adolescents and similarly obesity increased from 1.9% to 3.2%.29 Similar findings have been reported from a 5-year follow-up study in Thai school children where the prevalence of overweight in boys increased from 12.4% in 1992 to 21.0% in 1997.30

The primary findings of this study are also consistent with the substantial age-related declines in moderate to vigorous physical activity among both adolescent boys and girls previously reported in the USA31 32 and Finland.33 These results also showed that daily moderate to vigorous physical activity decreased of 42% over a 5-year period when adolescents were aged 12–16 years, which was similar to the 45% decline reported for American adolescents in the CATCH Study.34 Furthermore, the increase in sedentary time with age found in the present study is similar to increases reported by longitudinal studies in developed countries.35 36

This study can, through the cause–effect relationships examined, provide evidence to guide the formulation of appropriate and reasonable recommended levels of physical activity to prevent overweight/obesity in Vietnamese adolescents. The findings will also provide evidence to help develop recommendations for dietary behaviours or future designs of schools and neighbourhoods to ensure these environments are health promoting and meet the needs of Vietnamese adolescents during an age when there is rapid body growth.

Conclusions

The rapidly increasing prevalence of obesity as well as the significant decrease in time on moderate to vigorous activity and increase in sedentary time in adolescents in HCMC suggesting that this population is at increased future risk of non-communicable diseases. There is an urgent need to develop interventions to target this population to promote physical activity and decrease sedentary behaviour in order to prevent overweight/obesity. The complete data analysis of this cohort study will allow a full exploration of the role of environmental and lifestyle behaviours on adolescent overweight and obesity and also identify the factors most strongly associated with excess weight gain and the appearance of overweight and obesity in different age groups of adolescents from this large city in Vietnam. This information is needed to develop evidence-based public health interventions to control and prevent this epidemic from expanding among the youth of HCMC and other cities in Vietnam.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nestlé Foundation for funding this cohort; The University of Sydney World Scholars and the Hoc Mai foundation for Trang Nguyen HHD's PhD scholarships. We also thank the participating schools, students, parents and the study staffs involving in this study and the support from Nutrition Center.

Footnotes

To cite: Trang Nguyen HHD, Hong TK, Dibley MJ. Cohort profile: Ho Chi Minh City Youth Cohort—changes in diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and relationship with overweight/obesity in adolescents. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000362. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000362

Contributors: TNHHD, HKT and MJD all contributed to the conceptualisation, design and management of the study and all revised this manuscript critically. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the Nestlé Foundation grant (P673-1773).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to the data set is available from the corresponding author (nguyenhoang_doantrang@yahoo.com) or the principle investigator (hongutc@yahoo.com) in STATA format for academic researchers interested in undertaking a formally agreed collaborative research project.

References

- 1.Lobstein T, Frelut ML. Prevalence of overweight among children in Europe. Obes Rev 2003;4:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuong QT, Dibley MJ, Bowe S, et al. Obesity in adults: an emerging problem in urban areas of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:673–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong TK, Dibley MJ, Sibbritt D, et al. Overweight and obesity are rapidly emerging among adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2002-2004. Int J Pediatr Obes 2007;2:194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanhala M, Vanhala P, Kumpusalo E, et al. Relation between obesity from childhood to adulthood and the metabolic syndrome: population based study. BMJ 1998;317:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999;23(Suppl 2):S2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, et al. Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999;23(Suppl 8):S1–107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wabitsch M. Overweight and obesity in European children and adolescents: causes and consequences, treatment and prevention. An introduction. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159(Suppl 1):S5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumanyika SK. Minisymposium on obesity: overview and some strategic considerations. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:293–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.People Committee of Ho Chi Minh City Population and Health. Secondary Population and Health, 2010. http://www.eng.hochiminhcity.gov.vn/eng/news/default_opennew.aspx?cat_id=567&news_id=335 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Statistics of Ho Chi Minh City Statistics of Ho Chi Minh City, 2004. Ho Chi Minh: Department of Statistics of Ho Chi Minh City, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thanh LV, Chi HK, Danh HP. Scientific and Actual Context for Non-wealthy Threshold in Ho Chi Minh City 2006. http://www.hids.hochiminhcity.gov.vn/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=2d9fc8bd-2eb4-4c63-b25a-35d8ade4298a&groupId=41249 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;282:1561–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupont W, Plummer W. PS: Power and Sample Size. Secondary PS: Power and Sample Size. 2009. http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/twiki/bin/view/Main/PowerSampleSize [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Illinois: A Division of Human Kinetics Publishers Inc, 1991:184 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tammen H. Specimen collection and handling: standardization of blood sample collection. Methods Mol Biol 2008;428:35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong TK, Dibley MJ, Sibbritt D. Validity and reliability of an FFQ for use with adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:368–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth ML, Okely AD, Chey TN, et al. The reliability and validity of the adolescent physical activity Recall questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1986–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy LL, Booth ML, Okely AD. The reliability of the adolescent sedentary activity questionnaire (ASAQ). Prev Med 2007;45:71–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong TK, Trang NH, Dibley MJ. Validity and reliability of a physical activity questionnaire for Vietnamese adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (MS 4835073026381536). In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trost SG, Ward DS, Moorehead SM, et al. Validity of the computer science and applications (CSA) activity monitor in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:629–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong KT. Diet, Physical Activity, Environments And Their Relationship to The Emergence of Adolescent Overweight and Obesity in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. University of Newcastle, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trang NH, Hong TK, Dibley MJ, et al. Factors associated with physical inactivity in adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:1374–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001;38:115–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence; With a General Consideration of the Effects of Hereditary and Environmental Factors upon Growth and Maturation from Birth to Maturity. 2nd edn Oxford: Blackwell, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang KH, Nguyen HH, Dibley MJ, et al. Factors associated with adolescent overweight/obesity in Ho Chi Minh city. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010;5:396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TH, Tang HK, Kelly P, et al. Association between physical activity and metabolic syndrome: a cross sectional survey in adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2010;10:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trang NH, Hong TK, Dibley MJ. Active commuting to school among adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: change and predictors in a longitudinal study (2004 to 2009). Am J Prev Med 2012;42:120–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julia M, van Weissenbruch MM, Prawirohartono EP, et al. Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Tracking for underweight, overweight and obesity from childhood to adolescence: a 5-year follow-up study in urban Indonesian children. Horm Res 2008;69:301–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mo-suwan L, Tongkumchum P, Puetpaiboon A. Determinants of overweight tracking from childhood to adolescence: a 5 y follow-up study of Hat Yai schoolchildren. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:1642–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimm SY, Glynn NW, Kriska AM, et al. Longitudinal changes in physical activity in a biracial cohort during adolescence. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:1445–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:1601–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telama R, Yang X. Decline of physical activity from youth to young adulthood in Finland. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:1617–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, et al. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: the CATCH cohort. Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodersen NH, Steptoe A, Williamson S, et al. Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12. Ann Behav Med 2005;29:2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, et al. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1627–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.