Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether low self-rated health (SRH) is associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes.

Design

Population-based prospective cohort study.

Setting

Enrolment took place between 1992 and 2000 in four centres (Bilthoven, Heidelberg, Potsdam, Umeå) in a subcohort nested in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.

Participants

3257 individuals (mean ± SD age was 55.8±7.6 years and 42% women) with confirmed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

Primary outcome measure

The authors used Cox proportional hazards modelling to estimate HRs for total mortality controlling for age, centre, sex, educational level, body mass index, physical inactivity, smoking, insulin treatment, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and history of myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer.

Results

During follow-up (mean follow-up ± SD was 8.6±2.3 years), 344 deaths (241 men/103 women) occurred. In a multivariate model, individuals with low SRH were at higher risk of mortality (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.73) than those with high SRH. The association was mainly driven by increased 5-year mortality and was stronger among individuals with body mass index of <25 kg/m2 than among obese individuals. In sex-specific analyses, the association was statistically significant in men only. There was no indication of heterogeneity across centres.

Conclusions

Low SRH was associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes after controlling for established risk factors. In patients with diabetes with low SRH, the physician should consider a more detailed consultation and intensified support.

Article summary

Article focus

Is low self-rated health (SRH) associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes?

If so, is the association between SRH and mortality in individuals with diabetes moderated by socio-demographic and health-related variables?

Key messages

Low SRH was associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes after controlling for established risk factors. The association was homogeneous across the four European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition centres situated in three different European countries.

The association between low SRH and mortality was mainly driven by increased 5-year mortality in men and was stronger among individuals with body mass index <25 than among obese individuals.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates this research question in a population-based cohort of individuals with diabetes with long-term follow-up (up to a maximum of 14 years) in different European countries.

The association between SRH and mortality remained robust after controlling for potential confounders, including previous myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer, but we cannot rule out residual confounding from other comorbidity that was not assessed at baseline.

Introduction

Patients with diabetes have a 1.5–2.5-fold higher risk of death compared to a non-diabetic population.1–4 The excess mortality in patients with diabetes is mainly caused by a higher risk of cardiovascular (CV) mortality,3 4 but mortality due to cancer is also increased.5 It is of great importance to identify patients with diabetes with high risk of CV morbidity and mortality early on in the disease process in order to intervene with medication and lifestyle changes.6 Hence, risk engines7 or risk scores8 have been developed to identify the subjects at highest risk of developing CV. None of these tools have used subjective measures of health.

Self-rated health (SRH) is a subjective measure of health usually defined by responses to a single question such as ‘How do you rate your health?’ SRH has been associated with future health outcomes, such as cardiovascular events9 and mortality both in representative community samples10 and in defined patient cohorts.11–13 Although there is no consensus on what SRH really represents, SRH is drawing increasingly attention as a key parameter in healthcare, including health policy evaluation, population surveys and research.14 Previous research in different populations has suggested that the predictive strength of SRH for subsequent mortality may differ by sex,15 age,16 race,17 education level18 and experience of chronic disease.19 Studies evaluating SRH among individuals with diabetes are scarce. One previous study showed that SRH predicted vascular events and major complications in patients with diabetes.20

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether low SRH is associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes. Prospective studies investigating this research question have been restricted to short-term mortality (up to 4 years),21 22 whereas we can present data from a study with a mean follow-up of 8.6 years. As a secondary aim we investigated whether socio-demographic and health-related variables moderate the association between SRH and mortality in this cohort of individuals with diabetes.

Methods

Study population

The study was nested in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). EPIC is an ongoing cohort study, which consists of 519 978 men and women from 10 European countries. A detailed description of the study design and methods can be found elsewhere.23 24 Participants were 35–70 years at enrolment between 1992 and 2000 and were recruited predominantly from the general population residing in a given geographic area. Participants gave their written consent, and the study was approved by the ethical review boards of the International Agency for Research on Cancer and by the review boards at the local centres where participants had been recruited for the EPIC study. Originally, the EPIC centres in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the Netherlands contributed 7048 cases of self-reported diabetes at baseline. Self-reports of diabetes obtained at baseline were confirmed by additional information sources, which include the following depending on the available options in the different countries: contact with a medical practitioner, use of diabetes-related medication (eg, insulin and blood-glucose-lowering drugs), repeated self-report during follow-up, linkage to diabetes registries or a measure of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) above 6%.25 A total of 5542 cases of diabetes mellitus could be confirmed. We also included 870 participants whose diabetes diagnosis was confirmed within another project in EPIC, leading to a subcohort of 6412 individuals with confirmed diabetes at baseline.26 For the current study, only EPIC study centres that could provide data on SRH were included (Germany: Heidelberg and Potsdam; the Netherlands: Bilthoven; Sweden: Umeå). For this reason, 3155 participants (from the centres in Denmark, Italy and Spain) were excluded. The final data set therefore comprised 3257 participants from four EPIC study centres with a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus at baseline. No clear separation between type 1 and type 2 diabetes could be made.

Assessment of SRH

SRH was assessed at baseline using self-administered questionnaires in the native language. The questionnaires were somewhat differently formulated at each centre and were therefore standardised (described in online appendix). Given the low frequency of responses in the extreme categories (n=316 in the highest and n=241 in the lowest), we dichotomised the SRH variable by combining the two highest categories (high SRH) and the two lowest categories (low SRH) in conformity with previous studies.12 17 21

Covariates and outcome

Weight and height were measured with participants not wearing shoes. Each participant's body weight was corrected for clothing worn during measurement in order to reduce heterogeneity due to protocol differences among centres.27 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated after measurement of body weight and height, as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in metres squared). Overweight was defined as a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 and obesity as ≥30 kg/m2 according to the WHO guidelines. Underweight was defined as a BMI of <20 kg/m2. Since there were only 43 persons with underweight, we merged underweight with the normal BMI category. For the blood pressure measurements, uniform procedures were recommended. Hypertension was defined by a hypertension diagnosis or use of hypertensive medication or blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg. Further health-related variables were collected using questionnaires, including questions on educational level, smoking status (current smoker vs non-smoker or ex-smoker), physical activity level and medical history including history of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and cancer. Physical inactivity was defined using the Cambridge Index.28 Hyperlipidaemia was defined by use of medication for hyperlipidaemia.

Participants were followed from study entry until death, emigration, withdrawal or end of follow-up period. Causes and dates of deaths were ascertained using record linkages with central cancer registries, death indexes or by follow-up mailings and subsequent enquiries to municipality registries, regional health departments, physicians or hospitals. Mortality data were coded following the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD-10). ICD-10 codes I00–I99 were used to calculate proportions of cardiovascular mortality. HRs were calculated for all-cause mortality only since we did not have statistical power for analyses of specified mortality.

Statistical analyses

χ2 Test was used for testing proportions in categorical variables. Kruskal–Wallis test was used for significance testing in continuous variables. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Age was used as the primary time variable, with entry time defined as the subject's age in years at recruitment and exit time defined as the subject's age in years at death or censoring. Multivariate models were constructed to determine HRs adjusted for covariates. Age, centre, sex, BMI, physical inactivity, insulin treatment, hypertension and history of MI, stroke or cancer were tested as covariates and included in the multivariate model since they met the criteria of being significantly associated with both SRH and mortality during follow-up in men or in women. Given the low frequencies of previous MI, stroke and cancer, these covariates were combined in one variable in the multivariate analysis to ensure a good model fit. Interaction was tested by including interaction terms in the Cox proportional hazards analysis. The HRs were combined across centres using random-effects meta-analysis, and I2—the percentage of variation between centres due to real heterogeneity—was calculated. The first sensitivity analysis was performed to see if the strength of the association between SRH and mortality differed for short-term mortality and long-term mortality. Short-term mortality was defined as death within 5 years and long-term mortality as death after 5 years or more. This cut-off point was close to the median follow-up time of the decedents (5.4 years). The second sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding participants with underweight (BMI <20 kg/m2). A p value <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics V.19.0 except for the I2 index test, which was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.2.

Missing values

There was no information on history of stroke and cancer from the centre in Umeå (n=427), and these missing values were assigned to a separate category in multivariate analysis. The proportions of missing values for other variables were all <2.5% and coded as missing in multivariate analysis. Consequently, 85 persons including eight decedents were lost in the multivariate analysis.

Results

The mean follow-up time was 8.6 years (±2.3). Baseline characteristics for the 1903 men and 1354 women are presented in table 1. Mean age at baseline was 56.2 years (±7.1) for men and 55.4 years (±8.2) for women. Among the 3257 persons included in the study, there were 241 deaths (13%) in men and 103 deaths (8%) in women. Of the 344 persons who died, 40% were cardiovascular deaths, 52% were non-cardiovascular deaths and in 8%, the cause of death was unknown.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 3257 individuals with diabetes participating in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition

| Men (N=1903) | Women (N=1354) | |

| Age (years) | 56.2 (7.1) | 55.4 (8.2) |

| Self-rated health | ||

| High | ||

| Excellent | 10.5 | 8.6 |

| Good | 54.1 | 49.9 |

| Low | ||

| Moderate | 28.4 | 33.5 |

| Poor | 7.0 | 8.0 |

| Education | ||

| None | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| Primary school | 35.0 | 43.9 |

| Technical/professional school | 29.1 | 33.7 |

| Secondary school | 6.8 | 7.6 |

| Longer (including university degree) | 28.6 | 13.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.6 (4.3) | 29.5 (5.6) |

| Current smoking | 24.0 | 16.2 |

| Physical inactivity | 26.8 | 33.0 |

| Insulin treatment | 22.8 | 24.3 |

| Hypertension | 70.0 | 71.3 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 21.8 | 18.5 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 9.2 | 3.8 |

| History of stroke | 3.5 | 3.0 |

| History of cancer | 4.1 | 6.4 |

Data are presented as per cent or mean (SD).

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics in relation to categories of SRH. Persons with low SRH were younger, more frequently women, had higher BMI and had more frequently a history of MI or stroke compared to persons with high SRH. Moreover, in men with low SRH, insulin treatment was more common, and in women with low SRH, hypertension and a history of cancer were more common.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in relation to categories of self-rated health

| Men |

p Value |

Women |

p Value | |||||||

| Self-rated health |

Self-rated health |

|||||||||

| High |

Low |

High |

Low |

|||||||

| Excellent | Good | Moderate | Poor | Excellent | Good | Moderate | Poor | |||

| Age (years) | 57.1 | 56.6 | 55.2 | 55.4 | <0.001 | 53.8 | 55.8 | 55.4 | 54.1 | 0.001 |

| Education (%) | ||||||||||

| None | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.42 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 0.40 |

| Primary school | 35.9 | 33.1 | 36.8 | 42.4 | 35.3 | 44.6 | 44.5 | 44.8 | ||

| Technical/professional school | 31.8 | 28.4 | 29.3 | 28.8 | 41.4 | 33.2 | 32.3 | 34.3 | ||

| Secondary school | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 8.6 | 6.3 | 9.8 | 5.7 | ||

| Longer (including university degree) | 25.3 | 31.3 | 25.7 | 23.5 | 12.9 | 14.5 | 11.4 | 12.4 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6 | 28.4 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 0.05 | 28.1 | 29.2 | 30.0 | 31.1 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking (%) | 25.5 | 23.4 | 24.8 | 23.7 | 0.89 | 16.4 | 15.6 | 15.4 | 21.3 | 0.49 |

| Physical inactivity (%) | 20.6 | 26.3 | 26.6 | 41.1 | 0.001 | 18.3 | 32.8 | 35.8 | 39.8 | 0.002 |

| Insulin treatment (%) | 15.2 | 20.8 | 27.4 | 29.2 | 0.002 | 18.1 | 23.0 | 28.0 | 24.1 | 0.15 |

| Hypertension (%) | 67.5 | 68.5 | 74.0 | 70.7 | 0.11 | 56.9 | 72.4 | 72.3 | 75.0 | 0.004 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (%) | 22.0 | 20.4 | 24.1 | 21.8 | 0.42 | 14.7 | 18.6 | 19.0 | 20.4 | 0.69 |

| History of myocardial infarction (%) | 9.0 | 6.9 | 11.5 | 17.3 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 6.0 | 4.6 | 0.009 |

| History of stroke (%) | 2.8 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 9.5 | 0.001 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.07 |

| History of cancer (%) | 5.1 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 5.7 | 0.61 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 14.3 | 0.02 |

Data are presented as per cent or mean.

In a model adjusted for age and centre, low SRH was associated with increased mortality (table 3). In sex-specific analyses, this association was significant in men but not in women. After further adjustments for potential confounders, the association between low SRH and mortality was attenuated but remained significant in men and in both sexes combined. The fully adjusted HR for both sexes was 1.38 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.73). In a sensitivity analyses, we calculated HRs for low SRH for short-term mortality (participants who died within 5 years of follow-up, n=158) and long-term mortality (participants who died after 5 years or more, n=186). HR of low SRH for short-term mortality was 1.91 (95% CI 1.30 to 2.80) for men and 1.38 (95% CI 0.75 to 2.55) for women in the fully adjusted model. HR of low SRH for long-term mortality was 1.24 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.79) for men and 0.94 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.67) for women in the same multivariate model.

Table 3.

HRs of low (moderate or poor) versus high (excellent or good) self-rated health for all-cause mortality during follow-up

| Model 1*, HR (95% CI) | Model 2†, HR (95% CI) | Model 3‡, HR (95% CI) | |

| Both sexes | 1.56 (1.25 to 1.94) | 1.49 (1.19 to 1.86) | 1.38 (1.10 to 1.73) |

| Men | 1.75 (1.35 to 2.27) | 1.63 (1.25 to 2.12) | 1.52 (1.16 to 1.98) |

| Women | 1.35 (0.90 to 2.03) | 1.21 (0.80 to 1.83) | 1.11 (0.73 to 1.69) |

Adjusted for age and centre.

Adjusted for age, centre, sex, body mass index, physical inactivity, insulin treatment and hypertension.

Adjusted for age, centre, sex, body mass index, physical inactivity, insulin treatment, hypertension and history of myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer.

Interaction analyses were performed between SRH and covariates in relation to mortality. We found a significant interaction between SRH and BMI with Pinteraction value 0.03. When analysing HRs for SRH in different categories of BMI, we found stronger associations between SRH and mortality at lower levels of BMI, indicating an antagonistic interaction (table 4). For example, in the category normal or underweight, the fully adjusted HR for both sexes combined was 2.95 (1.71 to 5.10) compared to 1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) in obese individuals. Consequently, we performed a second sensitivity analysis by excluding persons with underweight (BMI <20 kg/m2, 43 persons) from the main analysis of SRH and mortality, which attenuated the fully adjusted HR from 1.38 to 1.36 (1.08 to 1.70) in both sexes combined. We found no statistical interaction between SRH and sex (Pinteraction value 0.30), age (Pinteraction value 0.22), education level (Pinteraction value 0.14), smoking (Pinteraction value 0.13), physical inactivity (Pinteraction value 0.24), insulin treatment (Pinteraction value 0.18), hypertension (Pinteraction value 0.23), hyperlipidaemia (Pinteraction value 0.16) and history of MI, stroke or cancer (Pinteraction value 0.29).

Table 4.

HRs of low versus high self-rated health for all-cause mortality by categories of BMI

| BMI classification | BMI (kg/m2) | CV mortality (%) | Model 1*, HR (95% CI) | Model 2†, HR (95% CI) | Model 3‡, HR (95% CI) | |

| Both sexes | Normal or underweight (n=646) | <25 | 38.3 | 2.81 (1.65 to 4.79) | 3.12 (1.81 to 5.37) | 2.95 (1.71 to 5.10) |

| Overweight (n=1408) | 25–29.9 | 37.3 | 1.46 (1.05 to 2.03) | 1.34 (0.96 to 1.89) | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.71) | |

| Obesity (n=1203) | ≥30 | 45.0 | 1.29 (0.90 to 1.85) | 1.20 (0.83 to 1.72) | 1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) | |

| Men | Normal or underweight (n=359) | <25 | 39.5 | 2.77 (1.49 to 5.15) | 3.61 (1.90 to 6.85) | 3.57 (1.88 to 6.78) |

| Overweight (n=921) | 25–29.9 | 39.0 | 1.62 (1.12 to 2.36) | 1.45 (0.99 to 2.14) | 1.33 (0.90 to 1.95) | |

| Obesity (n=623) | ≥30 | 47.5 | 1.57 (1.00 to 2.47) | 1.38 (0.87 to 2.18) | 1.31 (0.83 to 2.08) | |

| Women | Normal or underweight (n=287) | <25 | 35.3 | 3.14 (1.10 to 8.94) | 2.47 (0.79 to 7.66) | 1.87 (0.59 to 6.00) |

| Overweight (n=487) | 25–29.9 | 31.4 | 1.20 (0.61 to 2.38) | 1.04 (0.51 to 2.11) | 0.93 (0.45 to 1.91) | |

| Obesity (n=580) | ≥30 | 41.2 | 1.05 (0.56 to 3.85) | 0.95 (0.52 to 1.74) | 0.92 (0.50 to 1.69) |

Adjusted for age and centre.

Adjusted for age, centre, sex, BMI, physical inactivity, insulin treatment and hypertension.

Adjusted for age, centre, sex, BMI, physical inactivity, insulin treatment, hypertension and history of myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer.

BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular.

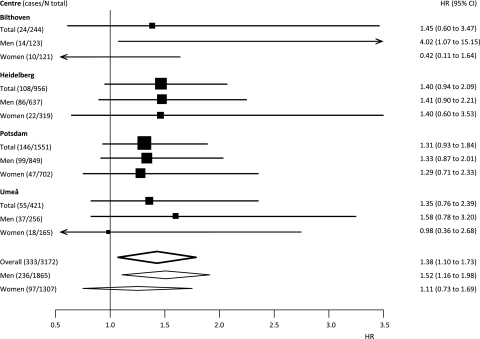

Figure 1 shows a forest plot with adjusted HRs for low SRH by sex and in both sexes combined for each centre. We found no clear indication of heterogeneity in the association between SRH and mortality across centres (I2 index=0).

Figure 1.

Forest plot showing adjusted HRs and 95% CIs for the centres included in the study investigating the association between low self-rated health and mortality in individuals with diabetes.

Discussion

We found that low SRH was associated with an increased risk of mortality in individuals with diabetes after adjusting for major established risk factors. This association was homogeneous across the four EPIC centres situated in three different European countries. The strength of the association between SRH and mortality in this study was similar to results in general populations.29 In sex-specific analyses, we found that the association between SRH and mortality was significant in men but not in women. However, the HR in women pointed in the same direction as in men, and we cannot rule out that the lack of significance was due to the lower statistical power to detect an association in women. Interestingly, the association between SRH and mortality was stronger among individuals with BMI of <25 kg/m2 than among obese individuals in both men and women. This finding could possibly be explained by the presence of other chronic diseases leading to low body weight, low SRH and higher risk of premature death. However, the association between low SRH and mortality remained significant even after the exclusion of persons with BMI of <20 kg/m2. Therefore, there are likely other factors contributing to the weaker association between SRH and overall mortality in obese individuals with diabetes. First, we found that the proportion of cardiovascular mortality was highest among obese individuals in both men and women, suggesting that the mortality pattern may be different at different levels of BMI. Previous research has shown that the link between SRH and mortality may be weaker for cardiovascular mortality than for cancer mortality or mortality from other causes.30 Second, we found that the obese individuals rated their health lower than individuals with normal weight, which is in line with studies on general populations.31 Previous studies have shown that obese persons may experience discrimination, stigmatisation and major limitations in daily life linked to their obesity.32 33 These factors will likely have a considerable impact on their health perception. We hypothesise that these factors related to obesity may overshadow other important health problems or health behaviours in the perception of health and possibly weaken the association between SRH and mortality in obese individuals.

The association between SRH and mortality has been of interest in medical research for several decades. Already in 1973, Maddox, one of the pioneers in this research field stated that SRH “clearly measure something more—and something less—than objective medical ratings”.34 It is still debated what information individuals rely on when rating their health. Qualitative research has suggested that SRH reflects a combination of specific health problems, general physical functioning and health behaviours.35 Cultural differences may also have an impact on SRH, even within Europe.36 A previous quantitative study from The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that low SRH is particularly predictive for respondents with self-reported history of circulatory system diagnoses and perception of symptoms but not for respondents without symptoms or diagnoses.19

Only a few studies have evaluated the association between SRH and mortality in well-defined cohorts of patients with diabetes.21 22 37 In 1994, Dasbach and colleagues found increased mortality in 987 patients with older onset of diabetes who rated their health as worse than other people of similar age. The average age in their study was 64.7 years (±11.0) compared to 55.8 years (±7.6) in our study. More recently, McEwen and coworkers21 found that SRH predicted mortality in an American multiethnic cohort of over 7000 patients with diabetes. However, their study was restricted to patients with longer duration of diabetes (diagnosed at least 18 months before survey) in managed care and a relatively short follow-up (the average length was 3.7 years). In the FIELD study, a controlled trial of fenofibrate performed in Australia, New Zealand and Finland, the mean duration of follow-up was even shorter, only 2.4 years. In this study involving 7348 patients with diabetes, Clarke and colleagues22 found that low SRH was associated with vascular events, diabetes complications and all-cause mortality. In our study, which was population-based, the participants were younger and followed for an average of 8.6 years. We found that the association between SRH and mortality was weaker and no longer statistically significant when we restricted the analysis to long-term mortality. These findings raise questions about the long-term predictiveness of a single self-rating of health and we therefore suggest that future research in individuals with diabetes should include repeated self-ratings and follow-up for long-term mortality.

There are some limitations in our study. Even if the association between SRH and mortality was robust when individuals with underweight were excluded, we cannot rule out other potential residual confounding from comorbidity other than MI, stroke or cancer that was not assessed at baseline health examinations. Moreover, the sample size in the present study did not allow any clear conclusions in relation to sex-specific analyses, and we could not make a separation between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The questions and the response alternatives on SRH were formulated somewhat differently and in the native language at each centre. The questions and answers were translated and standardised in four response alternatives, which may have led to some degree of misclassification, particularly for the centres in Bilthoven and Umeå (which had five response alternatives). However, the forest plot gave no indication that the standardisation in four response alternatives had a major impact on the risk estimates. The multivariate models used in this study were similar but not identical with equations used in risk engines7 and risk scores.8 Whether SRH adds predictive value over and above these models needs to be further analysed in future studies using adequate methods.38

Although more research is needed to gain a more complete understanding of the relationship between SRH and mortality in individuals with diabetes, we find that self-ratings of health are an inexpensive and time-efficient way to obtain subjective prognostic information that may be difficult to assess by objective health measurements. In patients with diabetes with low SRH, the physician should consider a more detailed consultation and intensified support.

Conclusions

This is the first study investigating the association between SRH and mortality in individuals with diabetes with a long-term follow-up in different European countries. We found that low SRH was associated with increased mortality in individuals with diabetes after controlling for established risk factors. The association was mainly driven by increased 5-year mortality in men and was stronger among individuals with BMI of <25 kg/m2 than among obese individuals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Wennberg P, Rolandsson O, Jerdén L, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000760. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000760

Contributors: PW, OR and UN were involved in the study concept and planned the analyses. PW, OR, HB, DS, RK, BT, AS, BBdM and UN contributed in the acquisition of the data. PW was responsible for statistical analyses and drafted the paper. PW, OR, LJ and UN interpreted the results. All authors participated in critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version. PW is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by a European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/Sanofi-Aventis grant. The European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes or Sanofi-Aventis had no role in the design or conduct of the study, collection or analysis of the data or preparation or approval of the manuscript and did not have any influence on the contents.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the IARC Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Hansen LJ, Olivarius Nde F, Siersma V. 16-year excess all-cause mortality of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulnier HE, Seaman HE, Raleigh VS, et al. Mortality in people with type 2 diabetes in the UK. Diabet Med 2006;23:516–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregg EW, Gu Q, Cheng YJ, et al. Mortality trends in men and women with diabetes, 1971 to 2000. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Grauw WJ, van de Lisdonk EH, van den Hoogen HJ, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: a 22-year historical cohort study in Dutch general practice. Diabet Med 1995;12:117–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, et al. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009;16:1103–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998;352:854–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, et al. ; United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in Type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101:671–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wilson PW, Larson MG, et al. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:20–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May M, Lawlor DA, Brindle P, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment in older women: can we improve on Framingham? British Women's Heart and Health prospective cohort study. Heart 2006;92:1396–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosworth HB, Siegler IC, Brummett BH, et al. The association between self-rated health and mortality in a well-characterized sample of coronary artery disease patients. Med Care 1999;37:1226–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker JD, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, et al. Does self-rated health predict survival in older persons with cognitive impairment? J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1895–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber Y, Benyamini Y, Goldbourt U, et al. Prognostic importance and long-term determinants of self-rated health after initial acute myocardial infarction. Med Care 2009;47:342–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vadla D, Bozikov J, Akerstrom B, et al. Differences in healthcare service utilisation in elderly, registered in eight districts of five European countries. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:272–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeg DJ, Kriegsman DM. Concepts of self-rated health: specifying the gender difference in mortality risk. Gerontologist 2003;43:376–86; discussion 372–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benyamini Y, Blumstein T, Lusky A, et al. Gender differences in the self-rated health-mortality association: is it poor self-rated health that predicts mortality or excellent self-rated health that predicts survival? Gerontologist 2003;43:396–405; discussion 372–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Moody-Ayers SY, Landefeld CS, et al. The relationship between self-rated health and mortality in older black and white Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1624–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowd JB, Zajacova A. Does the predictive power of self-rated health for subsequent mortality risk vary by socioeconomic status in the US? Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:1214–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Idler E, Leventhal H, McLaughlin J, et al. In sickness but not in health: self-ratings, identity, and mortality. J Health Soc Behav 2004;45:336–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes AJ, Clarke PM, Glasziou PG, et al. Can self-rated health scores be used for risk prediction in patients with type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care 2008;31:795–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEwen LN, Kim C, Haan MN, et al. Are health-related quality-of-life and self-rated health associated with mortality? Insights from Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD). Prim Care Diabetes 2009;3:37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke PM, Hayes AJ, Glasziou PG, et al. Using the EQ-5D index score as a predictor of outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Care 2009;47:61–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrari P, Slimani N, Ciampi A, et al. Evaluation of under- and overreporting of energy intake in the 24-hour diet recalls in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Public Health Nutr 2002;5:1329–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr 2002;5:1113–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sluik D, Boeing H, Montonen J, et al. Associations between general and abdominal adiposity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:22–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nothlings U, Boeing H, Maskarinec G, et al. Food intake of individuals with and without diabetes across different countries and ethnic groups. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011;65:635–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2105–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The InterAct Consortium Validity of a short questionnaire to assess physical activity in 10 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol. Published Online First: 17 November 2011. doi:10.1007/s10654-011-9625-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pijls LT, Feskens EJ, Kromhout D. Self-rated health, mortality, and chronic diseases in elderly men. The Zutphen Study, 1985-1990. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:840–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prosper MH, Moczulski VL, Qureshi A. Obesity as a predictor of self-rated health. Am J Health Behav 2009;33:319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life–a Swedish population study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:417–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, et al. Being ‘fat' in today's world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health Expect 2008;11:321–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maddox GL, Douglass EB. Self-assessment of health: a longitudinal study of elderly subjects. J Health Soc Behav 1973;14:87–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krause NM, Jay GM. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care 1994;32:930–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jylha M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998;53:S144–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in people with diabetes. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1775–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, D'Agostino RB, Jr, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72; discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.