Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impact of increased age on outcome from a strategy of early invasive management and revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

Design

Retrospective analysis of a national Acute Coronary Syndrome registry (ACACIA).

Setting

Multiple Australian (n=39) centres; 25% rural, 52% with onsite cardiac surgery.

Patients

Unselected consecutive patients admitted with confirmed ACS, total n=2559, median 99 per centre.

Interventions

Management was at the discretion of the treating physician. Analysis of outcome based on age >75 years was compared using Cox proportional hazard with a propensity model to adjust for baseline covariates.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were bleeding and a composite of any vascular event or unplanned readmission.

Results

Elderly patients were more likely to present with high-risk features yet were less likely to receive evidence-based medical therapies or receive diagnostic coronary angiography (75% vs 49%, p<0.0001) and early revascularisation (50% vs 30%, p<0.0001). Multivariate analysis found early revascularisation in the elderly cohort to be associated with lower 12-month mortality hazard (0.4 (0.2–0.7)) and composite outcome (0.6 (0.5–0.8)). Propensity model suggested a greater absolute benefit in elderly patients compared to others.

Conclusions

Following presentation with ACS, elderly patients are less likely to receive evidence-based medical therapies, to be considered for an early invasive strategy and be revascularised. Increasing age is a significant barrier to physicians when considering early revascularisation. An early invasive strategy with revascularisation when performed was associated with substantial benefit and the absolute accrued benefit appears to be higher in elderly patients.

Article summary

Article focus

To assess the impact of increased age on invasive management and revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndromes.

Key messages

Age is a barrier to treatment since elderly patients are less likely to receive evidence-based medical therapies and invasive management.

Invasive management when performed was associated with substantial benefit; greater absolute benefit was demonstrated in elderly patients compared to younger patients.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strengths of this study are that the data are large volume and comprise contemporary real-world practice.

The limitations of this study are that the reasons and decisions for offering or failing to offer invasive management or evidence-based therapy are not fully recorded.

There is no randomisation process within this registry.

Introduction

The management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is constantly evolving with new therapies and interventions tested in clinical trials. Subjects with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are at very high early risk, and timely reperfusion therapy with thrombolysis or primary angioplasty substantially reduces mortality.1 2 In patients with non-ST elevation syndromes (NSTEMI), an early invasive strategy with revascularisation where appropriate is recommended by international societies and supported by several prospective trials.3–5 This strategy is particularly beneficial in patients deemed to be at high risk—specifically those patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers or dynamic ECG changes.6 Age in isolation has been considered a risk factor for patients presenting with ACS yet a paradox exists that elderly patients >75 years are frequently under-represented in clinical trials, whereas in clinical practice, they constitute a significant proportion of the patient population.7 8

A poor outcome in the elderly population may be associated with more complex coronary disease, increased comorbidity and higher risk of complication from revascularisation procedures.9–11 Despite this, recent studies and large international registries have shown that the elderly population have substantially improved outcome with early invasive management, yet compared to younger patients an interventional strategy is less likely to be offered.5 12–17

The objective of this study was to assess the management of ACS in an elderly population using data taken from a national registry. Specifically, we planned to test the hypothesis that age in isolation does not adversely affect the outcome of patients presenting with ACS who are managed with an early interventional strategy and coronary revascularisation. We also explored the reasons that some elderly patients are not considered appropriate for an early invasive strategy.

Methods

The Acute Coronary Syndrome Prospective Audit (ACACIA, protocol number PM_L_0051) is a registry of Australian practice collected between 1 November 2005 and 31 July 2007 involving 39 hospitals across all states and territories of Australia. These sites were selected to be representative of rural (25%) and metropolitan (75%) centres, interventional (83%) and non-interventional (17%) centres and 52% of sites reported onsite cardiac surgery. Each site sought consecutive enrolment of between 100 and 150 patients admitted from the local emergency service for suspected ACS (median, 99). Patients presenting with ACS thought to be secondary to major trauma or surgery were excluded. Patients transferred into study centres were excluded if more than 12 h had passed since their initial presentation to enable more accurate assessment of immediate care.

Ethics approval was obtained from all sites, and written informed consent was obtained from all conscious patients. Access to medical records was permitted.

Definition of ACS and data collection

Patients presenting with suspected STEMI or NSTEMI were eligible for enrolment. The primary discharge diagnosis was determined by the investigators at each site but was confirmed by a central adjudication process. Stratification of data collection diagnoses was also centrally adjudicated to ensure consistency of enrolment from each centre. Allocation to non-cardiac chest pain was made when ACS was excluded or a positive alternative diagnosis was made, data from these patients were not included in the principle analyses. Standard clinical data were recorded including type and results of all investigations and medications. Early interventional strategy was defined as angiography at any point during the index acute admission, including emergency primary per-cutaneous intervention (PCI) for STEMI but excluded outpatient angiography. The use, time and extent of revascularisation by angioplasty (PCI) or surgery (coronary artery bypass surgery, CABG) was recorded. All data were collated by trained research coordinators. All-cause mortality was determined during the index admission and at 12 months. Any patients lost to follow-up were referred as a query to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Death Register to confirm status and cause of death. Data on non-fatal vascular events further revascularisation and unplanned hospital readmissions were recorded from hospital records and discharge codes.

Statistics

Primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 12 months. Secondary outcomes were thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) bleeding at 30 days and a composite of subsequent myocardial infarction, stroke, death and cardiovascular cause for unplanned hospital readmission at 12 months. We defined the elderly population as those patients older than 75 years, this value was selected since patients of this age and above have frequently been excluded from prospective clinical trials. Categorical outcomes and parameters were analysed with χ2 analysis or Fisher's exact test for 2×2 comparisons. Multivariate analysis of event-free survival and overall survival was performed using Cox proportional hazard. Survival curves were plotted to examine the effect of an early invasive strategy in the aged cohort. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate time-independent outcomes. To evaluate the impact of an early invasive strategy on 12 month mortality in patients >75 years and to control for substantial confounding clinical factors associated with increased age, a propensity analysis was performed using a non-parsimonious logistic regression model including age >75 years, gender, indigenous status, Killip class, GRACE score, cardiac arrest, normal ECG, ST segment depression or elevation, shock, pulmonary oedema or arrhythmia; presence of renal replacement therapy, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, diabetes, chronic airways disease, peripheral vascular disease, malignancy or atrial fibrillation; history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, PCI, CABG or stroke (c-index: 0.89). A logistic regression model for survival until 12 months including age, propensity score and early invasive management was then undertaken. This model was used to predict the expected mortality in ascending strata of age groups. These data are presented across the age groups further stratified by use of early invasive management. All data were analysed using commercially available software STATA V.13. Significance was sought at the 5% level.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 3402 patients were enrolled, and vital status was available for 3393 at 1 year. Discharge diagnosis of STEMI was recorded in 717 patients, NSTEMI in 1027 and unstable angina in 815 giving a study population of 2559. Patients excluded from analyses (843) were assigned to a variety of non-ACS diagnoses (including but not exclusive to: musculoskeletal chest pain, pericarditis, respiratory infection and pulmonary embolism). Elderly patients, >75 years comprised 27% (n=683) of the study population, baseline variables are shown in table 1. The younger group were more likely to be active smokers and to present with cardiac arrest. The elderly group presented more frequently in association with haemodynamic disturbance and other comorbidity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | <75 years (N=1876) | % | >75 years (N=683) | % | χ2 (Fisher's) |

| Male | 1380 | 74 | 372 | 55 | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1134 | 60 | 418 | 61 | 0.7 |

| Current smoker | 570 | 30 | 34 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Known coronary disease | 851 | 45 | 438 | 64 | 0.001 |

| Previous MI | 479 | 26 | 251 | 37 | 0.001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 93 | 5 | 121 | 18 | 0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 356 | 19 | 123 | 18 | 0.3 |

| Previous CABG | 234 | 12 | 150 | 22 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 512 | 27 | 171 | 25 | 0.25 |

| Hypertension | 1125 | 60 | 510 | 75 | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 137 | 7 | 139 | 20 | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 82 | 4 | 80 | 12 | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 96 | 5 | 84 | 12 | 0.001 |

| Elevated cardiac biomarkers | 1384 | 74 | 485 | 71 | 0.163 |

| Normal ECG | 506 | 27 | 155 | 23 | 0.03 |

| ST segment deviation (including BBB) | 894 | 48 | 338 | 50 | 0.4 |

| ST elevation | 577 | 31 | 138 | 20 | 0.001 |

| ST depression | 224 | 12 | 123 | 18 | 0.001 |

| Left bundle branch block | 73 | 4 | 72 | 11 | 0.001 |

| Killip 1 | 1589 | 85 | 448 | 66 | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 72 | 4 | 60 | 9 | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 68 | 3.6 | 11 | 1.6 | 0.009 |

| Arrhythmia on presentation | 115 | 6 | 40 | 6 | 0.8 |

BBB, bundle branch block; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, per-cutaneous intervention.

In hospital management

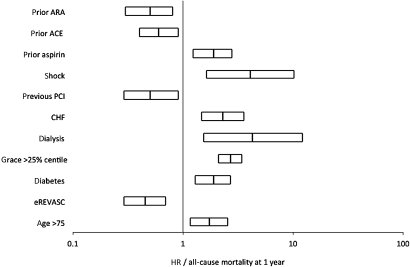

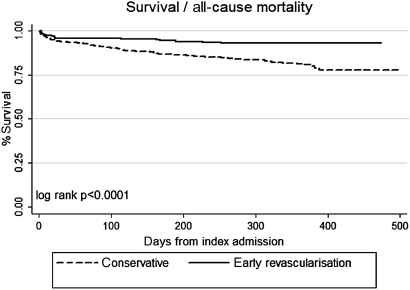

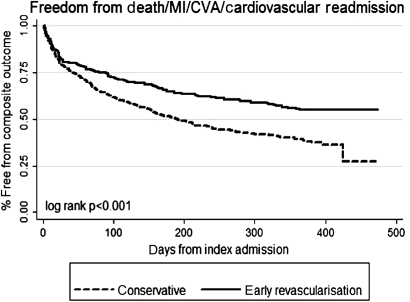

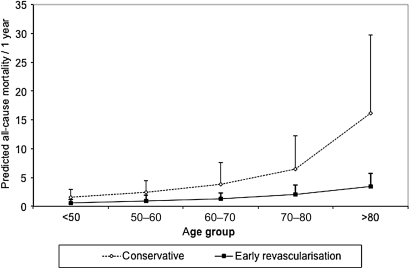

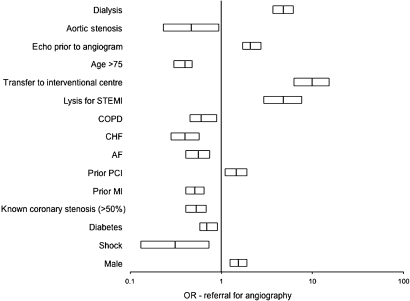

During in hospital care, the elderly group were less likely to be treated with evidence-based medical therapies and were less frequently referred for angiography (79% vs 49%, p=0.0001) (table 2). Revascularisation as a whole was therefore less frequently performed in the elderly cohort. The disparity in revascularisation was driven primarily by less frequent referral for diagnostic angiogram. If angiography was performed, then the rates of revascularisation were more comparable (61% vs 66%, p=0.04). Logistic regression of the whole cohort identified 13 variables that independently contributed to mortality at 12 months (figure 1). Among these variables, an age >75 years increased mortality risk (OR 1.7 (95% CI 1.2–2.6)) and early revascularisation reduced risk (OR 0.4 (95% CI 0.2–0.7)). Division of the data into subjects older than 75 years found early revascularisation to remain highly protective in terms of risk of all-cause mortality (OR 0.4 (95% CI 0.2–0.7)) and composite outcome (OR 0.6 (95% CI 0.5–0.8)) (figures 2 and 3). Predicted mortality based on the propensity model suggested further benefit associated with early revascularisation and incrementally greater benefit was projected in the higher age brackets (figure 4). We explored the factors associated with for non-referral for angiogram and for not performing revascularisation. Independent variables that appeared to contribute to non-referral for angiogram included age over 75 years, female gender, presence of diabetes and history of myocardial infarction (figure 5). Once an angiogram had been performed, fewer variables influenced the decision to perform revascularisation and neither gender nor age >75 years was contributory.

Table 2.

In hospital management

| Variable | <75 years (N=1876) | % | >75 years (N=683) | % | p Value |

| Aspirin | 1672 | 89 | 528 | 77 | 0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 1234 | 66 | 357 | 52 | 0.001 |

| 2b3a Agent | 163 | 8.7 | 36 | 5 | 0.004 |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 1410 | 75 | 520 | 76.1 | 0.6 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 1110 | 59 | 370 | 54 | 0.02 |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonist | 243 | 13 | 116 | 17 | 0.009 |

| HMG-CoA enzyme inhibitor | 1635 | 87 | 537 | 79 | 0.001 |

| B-blocker | 1346 | 72 | 446 | 65 | 0.002 |

| Functional test for ischaemia | 188 | 10 | 43 | 6.3 | 0.004 |

| Diagnostic angiography | 1401 | 75 | 335 | 49 | 0.001 |

| Echocardiogram | 758 | 40 | 293 | 42 | 0.26 |

| Angioplasty | 808 | 43 | 169 | 25 | 0.001 |

| Coronary surgery | 154 | 8.2 | 46 | 6.7 | 0.2 |

| Revascularisation if angiogram | 931 from 1401 | 66 | 203 from 335 | 61 | 0.04 |

| Reperfusion if (STEMI) | 420 | 72 | 80 | 60 | 0.008 |

| Primary PCI | 256 | 44 | 50 | 38 | 0.2 |

| Rescue PCI | 33 | 6 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.05 |

| TIMI bleed | 83 | 4 | 34 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Time to diagnostic angiogram (days) excluding primary PCI | 1.02±4.5 | 2.6±4.0 | 0.5* | ||

| Time to primary PCI (minutes) | 180.7±42.1 | 123±61.4 | 0.3* |

χ2 Statistic unless stated.

Unpaired t test.

PCI, per-cutaneous intervention; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Figure 1.

Box plot indicating HR contributing to all-cause mortality at 1 year in acute coronary syndromes cohort in multivariate analysis. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARA, angiotensin receptor antagonist; CHF, chronic heart failure; eREVASC, early revascularisation within the index admission; PCI, per-cutaneous intervention.

Figure 2.

Survival curve of elderly acute coronary syndromes cohort with respect to early revascularisation.

Figure 3.

Freedom from composite outcome in elderly acute coronary syndromes cohort with respect to early revascularisation. CVA, cerebrovascular accident (stroke); MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 4.

Predicted absolute mortality (error bars are SD) at 1 year calculated from propensity model.

Figure 5.

Box plot indicating HR contributing to likelihood of referral for diagnostic coronary angiography in the acute coronary syndromes cohort. AF, atrial fibrillation; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, per-cutaneous intervention; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

TIMI bleeding

There were 123 episodes of TIMI bleeding in the study cohort within 30 days of index presentation. Overall, age >75 years was not a risk factor for bleeding (HR 1.3 (0.86–1.9)) nor was there excess bleeding in the old versus younger cohorts (5% vs 4%, p=0.6). Early revascularisation was associated with a substantially higher risk of bleeding in both the young (10.5 (5.1–21)) and aged (14.9 (5.6–40)) cohort, and this relationship was independent of the use of aspirin, clopidogrel and anticoagulation at the time of presentation. Comparison limited to the patients who received early revascularisation (n=1134) did reveal excess bleeding in the aged cohort compared to the younger group (13.2% vs 7.6%, p=0.01).

Discussion

The ACACIA data set provides an outstanding insight into the management of ACS sourcing data from different types of hospital. These data in concordance with other studies show that elderly patients are more often managed conservatively, a particular barrier appears to be at the level of referral for diagnostic angiogram with less than half of the patients >75 years receiving this investigation. This observation is not a new finding12 18 and provides some evidence of referral bias; most young patients are offered an angiogram, whereas most elderly patients are not. Unfortunately, our data do not record the reason for this disparity since we do not have data on generalised extreme frailty, patient choice or a positive decision to palliate patients based on extensive comorbidity. There is no doubt that frailty may influence decision to treat individual patients conservatively,19 but it is extremely unlikely that these factors alone account for the fewer number or elderly patients offered an early invasive strategy. The reason for the apparent reluctance of clinicians to offer invasive management to some of their elderly patients is not clear. An obvious observation is that increased age is associated with mortality, yet the effect of age >75 years was less influential on mortality risk than presence of diabetes, heart failure and haemodynamic disturbance on presentation. Another possibility is the perceived risk of bleeding, we did observe a higher rate of TIMI bleeding at 30 days in the elderly cohort, although this effect did not translate to a change of mortality or composite outcome at 12 months. Furthermore, in our adjusted analysis, the absolute benefit of early revascularisation was positively associated with increased stratifications of age. This analysis is unsurprising since those patients at highest risk (such as the elderly) stand to gain most from an early invasive strategy, and this fact is consistent with the substantial impact of age on risk in scores, such as the GRACE score.20 The phenomenon of elderly patients deriving a greater absolute benefit than younger patients has previously been reported in subgroup analyses of the TACTICS TIMI 18 trial16 and from the crusade registry.17 The data from the ACACIA registry reinforce the message of these trials and other data demonstrating that age is not a bar to the benefits associated with invasive management and increased age should not be the dominant factor when contemplating management following hospitalisation with ACS. In the real world, some patients elect not to pursue an early invasive strategy, and this choice may be made more frequently by elderly patients, who may have concerns about their own frailty and long-term morbidity. Physicians may also judge that a patient has such substantial comorbidity that a palliative or limited approach should be undertaken.21 Despite these case-specific management decisions, it is clear from our data, however, that the elderly ACS population are underinvestigated and undertreated, and this may deny these patients the substantial benefit that is seen within 12 months. We encourage all physicians who manage patients with ACS to avoid using advanced age as reason to manage some patients conservatively.

Conclusions

Elderly patients comprise a large group of the ACS population. Despite having higher baseline risk, they are less likely to be offered evidence-based medical therapies and substantially less likely to be investigated invasively with a view to early revascularisation. The effect of an early invasive strategy with revascularisation was associated with improvements in survival and in the composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, death and cardiovascular cause for readmission, at the expense of a higher incidence of TIMI bleeding. Adjustment for baseline covariates using a propensity model suggested greater absolute benefit in patients at advanced age.

Limitations

The ACACIA data represent a real-world registry; individual decisions on patient management such as reasons for not offering an early invasive strategy were not recorded. Hence, the issue of residual selection bias leading to confounding cannot be fully accounted for. While other techniques such as ‘instrument variable analysis’ offer alternative approaches to this problem, determining a viable instrument remains challenging. Nevertheless, these data are consistent with other reported literature. Since there was no randomisation process in this registry data, all statistical relationships are reported as associations rather than implied causation.

The geographical challenges of healthcare in Australia are reflected in some of the data such as persisting use of thrombolysis and rescue or convalescent angioplasty. Our data include all patients diagnosed ACS including those with ST elevation myocardial infarction; we did not exclude these patients from analyses since the main interest of the paper was on the impact on age overall, rather than an analysis of a select population of ACS. Our data, therefore, differ from the other major studies of age on outcome that were limited to non-ST elevation myocardial infarctions.5 17 18

Transfer from a non-interventional centre to an interventional centre was positively associated with an early invasive strategy. It is possible that further referral bias occurs at this level since cardiologists may preselect those patients in whom they expect the best outcomes, especially if transfer involves air travel. However, our data were carefully selected to be representative of real-world cardiology practice including both metropolitan surgical centres and rural district hospitals and evidence of bias in referral based on age or transfer is worthy of discussion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Investigators (by state): Australian Capital Territory: Dr Tan Ren, Canberra Hospital. New South Wales: Associate Professor David Brieger, Concord Hospital; Associate Professor MA Fitzpatrick, Nepean Hospital; Professor Peter Fletcher, John Hunter Hospital; Dr David Rees, St George Hospital; Dr Craig Juergens, Liverpool Hospital; Dr Jonathon Waites, Coffs Harbour Hospital; Dr Greg Nelson, Royal North Shore Hospital; Dr Michael Sinclair, Dubbo Base Hospital. Victoria: Dr John Amerena, Geelong Hospital; Professor Yean Lim, Western Hospital; Dr Mark Horrigan, Austin Health; Dr LeeanneGrigg, Royal Melbourne Hospital; Dr David Eccleston, Northern Hospital Clinical Trials Unit; Dr Greg Szto, Peninsula Private Hospital; Associate Professor Gishel New, Box Hill Hospital; Dr Christopher Medley, Wodonga Regional Health Service. Queensland: Dr Steve Coverdale, Nambour General Hospital; Professor Laurie Howes, Gold Coast Hospital; Dr David Cross, Wesley Hospital; Dr Paul Garrahy, Princess Alexandra Hospital; Dr Darren Walters, Prince Charles Hospital; Dr Spencer Toombes, Toowoomba Health Services; Dr Prasad Challa, Cairns Base Hospital; Dr Kumar Gunawardane, Townsville Hospital; Dr William Parsonage, Royal Brisbane Hospital; Dr Raj Shetty, Rockhampton Hospital. South Australia: Professor Derek Chew, Flinders Medical Centre; Professor Stephen Worthley, Royal Adelaide Hospital; Professor John Horowitz, Queen Elizabeth Hospital; Dr Samuel Varughese, Mt Gambier Hospital; Dr Christopher Zeitz, Port Augusta Hospital; Dr MargaretArstall, Lyell McEwin Hospital. Western Australia: Dr Jamie Rankin, Royal Perth Hospital; Dr Barry McKeown, Fremantle Hospital; Dr Johan Janssen, Kalgoorlie Regional Hospital; Associate Professor Joseph Hung, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Tasmania: Dr Philip Roberts-Thomson, Royal Hobart Hospital. Northern Territory: Dr Marcus Iton, Darwin Private Hospital; Dr Alex Brown, Menzies School of Health Research.

Footnotes

To cite: Malki CJ, Prakash R, Chew DP. The impact of increased age on outcome from a strategy of early invasive management and revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndromes: retrospective analysis study from the ACACIA registry. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000540. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000540

Contributors: CM analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RP helped analyse the data and edited the final draft of the manuscript. DPC developed the initial concept and supervised analysis and editing of the final draft of the paper. DPC is the guarantor of this submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patients in this registry signed standard consent forms approved by the Flinders Medical Centre ethics committee in South Australia.

Ethics approval: Flinders Medical Centre Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The original ACACIA data can be requested by permission from DPC, Flinders Medical Centre, Adelaide, South Australia.

References

- 1.Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, et al. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet 1996;348:771–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1598–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollack CV, Jr, Braunwald E. 2007 update to the ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: implications for emergency department practice. Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:591–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Am Heart J 2005;149:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoenig MR, Aroney CN, Scott IA. Early invasive versus conservative strategies for unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the stent era. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD004815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation 2007;115:2570–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordijk-Trion M, Lenzen M, Wijns W, et al. Patients enrolled in coronary intervention trials are not representative of patients in clinical practice: results from the Euro Heart Survey on Coronary Revascularization. Eur Heart J 2006;27:671–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagur R, Bertrand OF, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Comparison of outcomes in patients > or =70 years versus <70 years after transradial coronary stenting with maximal antiplatelet therapy for acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:624–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes RD, Alexander KP, Marcucci G, et al. Outcomes in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes randomized to enoxaparin vs. unfractionated heparin: results from the SYNERGY trial. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1827–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assali AR, Moustapha A, Sdringola S, et al. The dilemma of success: percutaneous coronary interventions in patients ≥75 years of age—successful but associated with higher vascular complications and cardiac mortality. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2003;59:195–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagnall AJ, Goodman SG, Fox KA, et al. Influence of age on use of cardiac catheterization and associated outcomes in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:1530–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skolnick AH, Alexander KP, Chen AY, et al. Characteristics, management, and outcomes of 5,557 patients age > or =90 years with acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1790–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devlin G, Gore JM, Elliott J, et al. Management and 6-month outcomes in elderly and very elderly patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: the global registry of acute coronary events. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1275–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao RL, Xu B, Chen JL, et al. Immediate and long-term outcomes of drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: comparison with bare-metal stent implantation. Am Heart J 2008;155:553–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach RG, Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, et al. The effect of routine, early invasive management on outcome for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann internal medicine 2004;141:186–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, et al. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE quality improvement initiative. JAMA 2004;292:2096–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan RT, Yan AT, Tan M, et al. Age-related differences in the management and outcome of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2006;151:352–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huerre C, Guiot A, Marechaux S, et al. Functional decline in elderly patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes: impact on midterm outcome. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2010;103:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta RH, Sadiq I, Goldberg RJ, et al. Effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention compared with that of thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2004;147:253–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekerstad N, Lofmark R, Carlsson P. Elderly people with multi-morbidity and acute coronary syndrome: doctors' views on decision-making. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:325–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.