Abstract

The production of hyperpolarized fluids in continuous mode would broaden substantially the range of applications in chemistry, materials science, and biomedicine. Here we show that the rational design of a heterogeneous catalyst based on a judicious choice of metal type, nanoparticle size and surface decoration with appropriate ligands leads to highly efficient pairwise addition of dihydrogen across an unsaturated bond. This is demonstrated in a parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP) experiment by a 508-fold enhancement (±78) of a CH3 proton signal and a corresponding 1219-fold enhancement (±187) of a CH2 proton signal using nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR). In contrast, bulk metal catalyst does not show this effect due to randomization of reacting dihydrogen. Our approach results in the largest gas-phase NMR signal enhancement by PHIP known to date. Sensitivity-enhanced NMR with this technique could be used to image microfluidic reactions in-situ, to probe nonequilibrium thermodynamics or for the study of metabolic reactions.

The sensitivity of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and imaging (MRI) experiments, two of the most common analytical techniques in chemistry and biomedicine, is severely limited by the inherently small Zeeman splitting energy in a magnetic field relative to the thermal energy. This imposes severe limits on the minimum sample size, spatial resolution or acquisition time required for good quality data. The main strategies used to mitigate issues of low sensitivity and improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in NMR and MRI1,2 fall into two categories: (1) use of “hyperpolarization” techniques3,4 and (2) development of better detectors5,6,7,8. With the hyperpolarization approach3,4, the goal is to produce a nonequilibrium population of nuclear energy levels that translates to a large magnetic polarization.

Parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP)9,10 is one such way to enhance the polarization and tackle insensitivity problems. In homogeneous reactions catalyzed by transition metal complexes11,12, PHIP has been a useful analytical tool capable of probing short-lived reaction intermediates. Compared to thermal polarization, up to four orders of magnitude signal enhancement is possible for commonly used field strengths12,13. Unfortunately, this limit is never attained. In heterogeneously catalyzed reactions, the achieved performance of PHIP in the gas phase is far below the theoretically achievable limits14,15. Analytical techniques based on PHIP in heterogeneous catalysis are rare because of the lack of suitable catalysts that lead to complete pairwise addition.

Approaching the theoretical limit of a pure quantum state could lead to important new applications: in situ study of nonequilibrium reactions16,17, biomedicine18,19, microreactors6, quantum computing20, contrast agents for MRI, void space imaging21, detection of insensitive nuclei12,22 and long-term storage of polarization23. Heterogeneous catalysts are advantageous in comparison to their homogeneous counterparts because the products can be kept free from catalyst contaminants and the catalyst can be reused for extended periods in a continuous-flow reaction without the need for costly separation steps24.

In this work, we demonstrate the generation of highly polarized fluids from parahydrogen through the use of rationally-designed, ligand-capped nanoparticles. The results suggest that quenching of intermolecular exchange of hydrogen atoms (IEHA) adsorbed on metal nanoparticles depends on the interplay of mass transport and precise properties of the catalyst. The IEHA leads to a suboptimal PHIP polarization. The nuclear-spin polarization achieved in the gas phase is equivalent to that which would be obtained by cooling the sample to sub ∼mK temperatures or polarizing in a ∼MT field, neither of which can be easily achieved at present.

In the PASADENA (Parahydrogen And Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment) experiment of Weitekamp10, high quantum purity parahydrogen is reacted in a high magnetic field and the two protons are added pairwise to the substrate molecule. Chemical inequivalence of the protons results in para to ortho conversion accompanied by a strong polarization owing to the initial high purity. Two minimum requirements for PHIP are9,10 (i) pairwise interaction of parahydrogen to a reaction molecule (ii) relaxation rate that is lower than the reaction rate. The signal in a PASADENA experiment2 is distinguished by its antiphase signature where the associated NMR peak has both positive and negative lobes10 (see Figure 3).

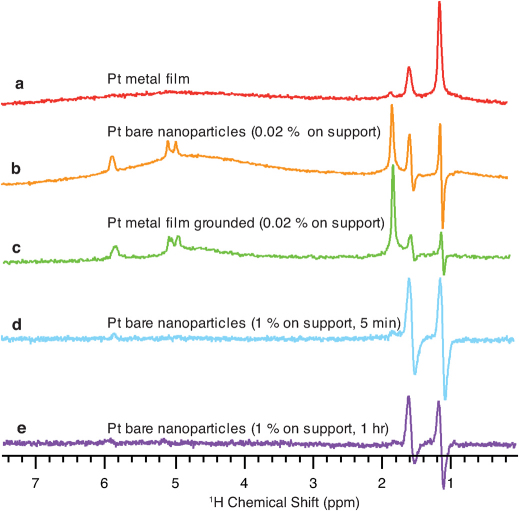

Figure 3. Hydrogenation activity monitored by PHIP-NMR in bare platinum metal and nanoparticles.

(a)1H NMR spectrum for hydrogenation reaction of propene with parahydrogen using platinum metal film shows no PHIP features. A PHIP feature in the NMR spectrum is characterized by a resonace peak that has two lobes, one pointing upwards and the other downwards (antiphase signal). In this reaction, this is examined by looking at the peaks at 1.1 ppm and 1.6 ppm for methyl and methylene protons, respectively. The rest of the spectra exhibit signature PHIP characteristics when the following samples were used; (b) ∼10 nm bare platinum nanoparticles obtained from incipient wetness impregnation, 0.02wt% Pt/TiO2; (c) ∼ 100 nm bare particles obtained through the grinding of platinum metal film, 0.02wt% Pt/TiO2; (d) platinum nanoparticles with 1wt% Pt/TiO2, in the first five minutes of the reaction and (e) platinum nanoparticles with 1wt% Pt/TiO2, after one hour of reaction. A noticeable decrease in PHIP signal intensity is observed from (d) to (e) because of particle agglomeration due to elevated temperatures in the reaction.

Results

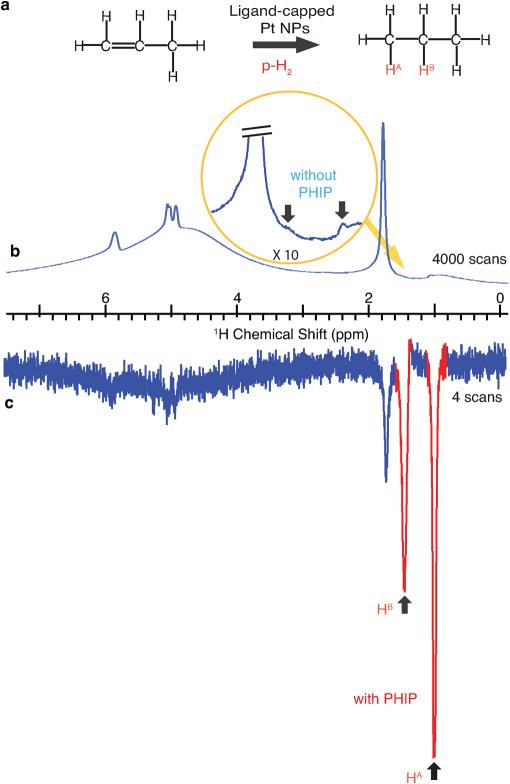

A sample of a supported heterogeneous catalyst was made by soaking a piece of glass wool (SiO2) in a solution of p-mercaptobenzoic acid-capped (2.5±0.4) nm platinum (Pt) nanoparticles (NPs) to yield ∼1-wt% Pt/SiO2 (catalyst-1). The PHIP efficiency through hydrogenation is quantified by comparing the 1H signal enhancement (E) in a reaction of parahydrogen and propylene. The NMR signal ratio of a parahydrogen polarized molecule to a thermally polarized molecule is the direct measurement of E. Here, E values of 508±78 and 1219 ±187 are observed experimentally (not extrapolated) for methyl and methylene protons, respectively (Figure 1). In comparison, the polarization observed previously14,15 in a gas phase reaction were rather modest, where E < 100. The value of E can be converted to percentage polarization as follows. For an experiment conducted at 4.7T, 300K and 45° flip angle, the maximum achievable signal enhancement is given by the formula Emax = 31240f, where f is the uncompensated fraction associated with parameters such as fraction of pH2 (1/3 for hydrogen that is 50% para)15,25. Additional contributions to the uncompensated fraction arise due to field strength (1/2 at 9.4 T) and stoichiometric ratio describing the number of protons contributing to the signal (in the case of propane, 1/6 when hyperpolarized signal is attributed to one proton in a group of 6 thermally polarized methyl protons; 1/2 when hyperpolarized signal is attributed to one proton in a group of two thermally polarized methylene protons). Therefore, under “theoretically ideal” conditions of a PASADENA experiment at 9.4 T, hydrogen that is 50% para-enriched, the maximum signal enhancement factor, using f = 1/36, for a propane methyl proton would be 868. The enhancement factor of 508±78 observed here in methyl proton corresponds to a nuclear-spin polarization of (60±10)%. This total gain in SNR in a gas-phase PASADENA experiment (heterogeneous reaction) – more than an order of magnitude higher than previously achieved ∼3%14,15 – is unprecedented. There are, of course, 8 protons on the propane molecule – 6 of which are thermally polarized – and the above analysis is valid for the two added protons in isolation. The overall “proton signal enhancement” should account for the dilution with respect to the total number of protons.

Figure 1. Synthesis and detection of strongly hyperpolarized gas from hydrogenation using p-MBA-capped platinum nanoparticles.

(a) reaction of propene with parahydrogen to produce propane. (b)1H NMR peaks showing no polarization effect in the product molecule vs (c)1H NMR peaks with 508-fold signal (±78) enhancement of a methyl proton (see SI for details) due to the polarization effect. Experiments were conducted under identical conditions using ‘normal’ H2 in (b) and 50% parahydrogen in (c) The spectra are represented in absolute magnitude mode to help us assess the signal enhancement factor.

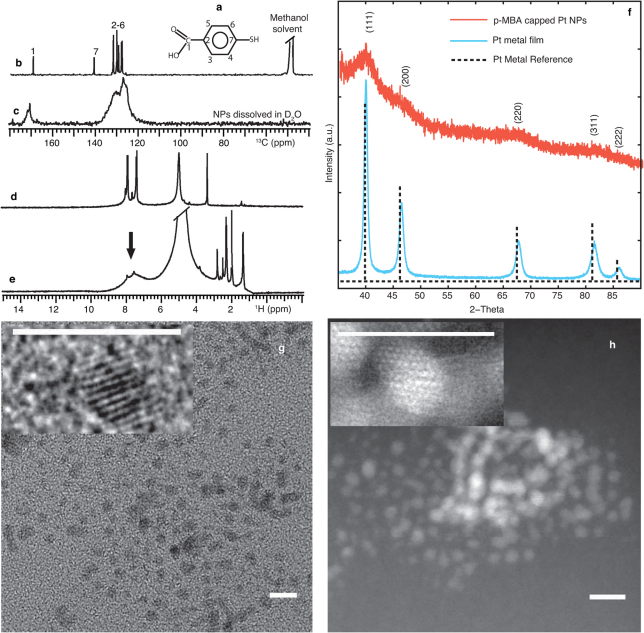

To confirm that catalyst-1 consisted of ligand-capped NPs, we performed a characterization of p-mercaptobenzoic-capped Pt NPs through NMR, TEM, XRD, UV-Vis and TGA. The results (Figure 2) indicate the presence of surface-bound ligands on (2.5±0.4)nm Pt NPs used in catalyst preparation with no free Pt ions (see Methods for details). Ligand-capped NPs with 1% Pt/TiO2 deposited on SiO2 glass wool (catalyst-2) showed much higher PHIP signals than the NP catalyst investigated by Koptyug and co-workers14, who used supported bare Pt NPs. Also note that PHIP is about a factor of three higher in catalyst-1 compared to catalyst-2, but catalyst-1 shows lower activity in terms of product formation.

Figure 2. Characterization of p-MBA-capped platinum nanoparticles.

(a) p-MBA used in the synthesis of ligand-capped nanoparticles; (b) (c) Solution 13C-NMR spectrum of free ligands and surface-bound ligands, respectively. (d) (e) Solution1H-NMR spectrum of free ligands and surface-bound ligands, respectively. The presence of broad peaks in the NMR spectrum indicates surface bound ligands on heterogeneous surfaces. The NMR line broadening shown by an arrrow in (e) is due to a distribution of chemical shifts and associated broadening mechanism. (f) XRD powder pattern acquired in p-MBA-capped platinum nanoparticles (upper) and platinum metal film (middle) overlaid on top of the dotted reference line for bulk platinum metal. The XRD diffraction peak broadening in PtNP is due to a lack of long-range order in small crystallite sizes. (g) HRTEM and (h) HRSTEM images of the nanoparticles with average particle core diameter 2.5 ± 0.4 nm . Scale bar, 5 nm.

Discussion

We now examine key aspects of the reaction based on the fact that PHIP is evidence for pairwise hydrogenation9,10. Consider the case of a bulk metal surface. Figure 3a shows no PHIP signal in the product molecule for hydrogenation of propylene with parahydrogen over Pt metal film. The results are in agreement with the conventional view that rules out pairwise addition of molecular hydrogen during hydrogenation on metal surfaces because bulk metals lead to randomization of atoms and therefore loss of quantum correlations. A similar experiment performed utilizing ∼10 nm bare Pt NPs in a low loading (0.02-wt% Pt/TiO2) prepared through incipient wetness impregnation yields a small but unmistakable PHIP signal (Figure 3b). A pairwise addition of parahydrogen by bare-NPs was further confirmed by performing the reaction on supported ∼100 nm particles (0.02-wt% Pt/TiO2) obtained by grinding the Pt metal film. Both 10 nm and 100 nm particles show low but detectable PHIP (Figure 3c). When the bare-Pt particle concentration on the support was increased to ∼1 wt% Pt/TiO2, both the PHIP and hydrogenation rate increased (Figure 3d). However, PHIP decreased significantly after one hour of reaction (Figure 3e). The reason for this is because densely populated nanoparticles coalesce to form bulk metal grains due to the heat of the reaction (∼250°C in the sample) and give a grayish color. The latter could be observed visually on the powder support. As a result, the chemically agglomerated nanoparticles, whose properties become similar to that of a bulk metal, result in low polarization. Whether or not the inefficiency in polarization on metal surfaces is due to the fast relaxation of parahydrogen, and the extent of such a relaxation mechanism, is not known precisely. However, we have observed a small PHIP signal using Pt particles as big as 1–50 µm obtained by cutting 50 µm-diameter platinum wire using a razor blade. This provides evidence that parahydrogen relaxation may not likely be the primary cause of signal loss in PHIP, assuming that 1–50 µm particles behave as bulk Pt metal.

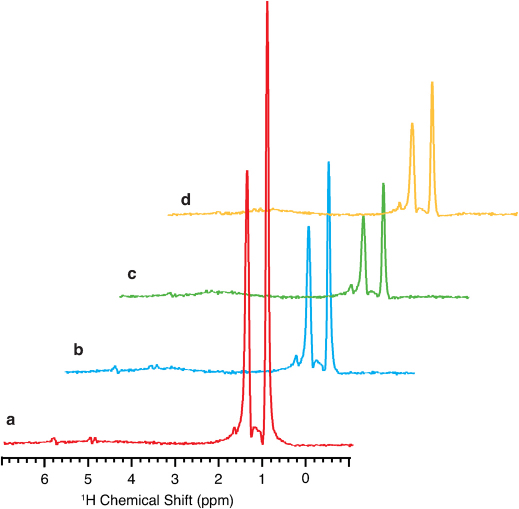

The next question to be addressed pertains to the activity of dihydrogen on (bare) bulk metal surfaces. The previous experiment was modified using (i) Wilkinson's catalyst24 capable of yielding strong PHIP (our “control” experiment) and (ii) 50/50% H2/D2 gas mixture. A 2:1 PHIP ratio for 100% H2 vs 50/50% H2/D2 is used as a reference (Figure 4a–b) prior to an IEHA test on metal surface (50/50% H2/D2 mixture flowing into Pt metal film, then into the parahydrogen conversion reactor21). The parahydrogen produced this way yields PHIP signals lower by a factor of two compared to the absence of Pt film (Figure 4c). Thus, IEHA occurs on bulk Pt. The comparison of PHIP intensities indicates an outcome composition of 25% H2, 25% D2 and 50% HD after the exchange on bulk Pt.

Figure 4. Intermolecular exchange of hydrogen atoms (IEHA) on bulk metal and nanoparticle surfaces.

1H NMR spectra of propene hydrogenation reaction with parahydrogen produced from parahydrogen converter at 77 K under the following conditions and gas mixtures. (a) using 100% hydrogen gas; (b) 50/50% hydrogen/deuterium gas mixture; (c) 50/50% hydrogen/deuterium gas mixture in contact with platinum metal before flowing into a parahydrogen converter and (d) 50/50% hydrogen/deuterium gas mixture in contact with TiO2 supported p-MBA-capped platinum nanoparticles before flowing into the parahydrogen converter. The PHIP NMR signal in (c) and (d) is a factor of two less than (b). This confirms that IEHA occurs on both metal and supported nanoparticles if sufficient catalyst is present across the bed in a gas flowing system.

Exchange is not limited to bulk Pt. A similar experiment performed using p-mercaptobenzoic acid-capped nanoparticles prepared with 0.1 g of 1-wt% Pt/TiO2 loading exhibits IEHA as judged from a1H-PHIP spectrum. When the amount of catalyst is increased tenfold (i.e., 1 g of 1-wt% Pt/TiO2 loading), the amplitude of the PHIP intensity decreased by a factor of two (Figure 4d) and the observed result is similar to that obtained with Pt film (Figure 4c). This implies that IEHA does take place on the NP catalyst supported on TiO2 powder and the exchange rate is proportional to the NP content and amount of catalyst present. Thus, PHIP efficiency increases when particle dispersivity increases and concentration decreases. This observation is in agreement with previously reported26 evidence that spillover of dissociating hydrogen occurs from metal surface to oxide support, altering the rates of IEHA and hydrogenation. Both dissociation of hydrogen molecule and spillover of hydrogen atoms influence the efficiency of PHIP14.

Koptyug and co-workers14 first reported the observation of a modest fraction (∼3%) of PHIP in hydrogenation reactions catalyzed by metal nanoparticles14,27. Their result was remarkable and surprising in light of the conventional view in catalysis that hydrogenation reactions at metal surfaces involved IEHA and would therefore be incompatible with the idea of pairwise hydrogenation28. These same investigators14 hypothesized that localization of catalytic sites on NP surfaces was responsible for the observation of PHIP signals. The results of our in-depth investigations support their hypothesis. Our main finding is that PHIP effects become most efficient when surface-binding ligands are utilized to control size, prevent IEHA and facilitate immobilization on supports. Surface-binding ligands likely confine the reaction sites and prevent NPs from coalescing to bulk metal; both factors minimize IEHA. Furthermore, specific functional groups in the ligands, such as the carboxylic group in the present case, render NPs soluble in aqueous solvents and upon drying lead to adsorption of particles on a support as has been shown to be important in heterogeneous catalysis29,30.

The ligand-capped metal particles, which were designed based on the hypothesis of spatial confinement of nanometer-scale metal sites, appear to be ideal vehicles for producing highly polarized NMR signals from heterogeneous reactions. In addition, this property of NP catalysts provides a new tool to investigate industrially important heterogeneous reactions & mechanisms, intermediates and surface interactions.

Methods

The hydrogenation reactions were carried out directly inside the NMR tube with a different combination of flow rates for propene and parahydrogen. Hydrogen used in the PHIP investigations was enriched to 50% para (using liquid nitrogen), as confirmed by1H NMR. The enhancement factor of 508±78 observed in methyl proton corresponds to a nuclear-spin polarization of (60±10)% if it is extrapolated to initial conditions of 100% para, 4.7T NMR field and in the absence of dilution of a polarized spin in propane. The 100% para can be realized using liquid helium temperatures instead.

The bare-platinum film and nanoparticles were prepared through incipient wetness impregnation using 200 µL aqueous solutions of 200 mM and 200 µM chloroplatinic acid, respectively. A flat surface 2 cm × 2 cm silicon dioxide (SiO2) filter paper (0.036 g) was used for preparing a platinum film and porous TiO2 nanopowder for supporting bare nanoparticles. The formation of metal film and nanoparticles occurred by reduction of platinum ions with H2 gas inside a 10 mm NMR tube kept at 140°C.

The ligand-capped 2.5±0.4 nm platinum nanoparticles were synthesized by reduction of chloroplatinic acid (0.38 millimoles, Sigma Aldrich) in the presence of p-mercaptobenzoic acid, p-MBA, (0.38 millimoles, Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in 30 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF). As soon as the metal precursor and ligands were dissolved in solution, an approximately ∼8 mL super-hydride solution (1 M in THF from a fresh bottle) was added in a minute under vigorous stirring to yield a brown product of p-MBA-capped nanoparticles. The brown product was precipitated by adding excess acetone, separated by centrifugation and re-dissolved in water. Adding excess acetone in the solution results in nanoparticle precipitation. Further rinsing with THF and acetone twice results in clean nanoparticles, as characterized by 13C and1H NMR. The lack of Ultraviolet-visible (Uv-vis) peak at 262 nm confirmed the absence of platinum ions in solution of nanoparticles (See SI). The high-resolution TEM and STEM images were obtained using a Titan STEM microscope operating at 300 kV. The measured average particle core diameter from TEM images is 2.5±0.4 nm.

The XRD powder patterns were acquired by a 1.54-Angstrom X-ray source on samples deposited on glass slides. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) indicates that surface-bound ligands decompose completely around 400°C, and ligands contribute approximately 13% weight in this nanoparticle system (see SI). Although the observed ligand composition is a relatively small fraction of the total weight, the estimated ligand coverage density is quite high (∼5 ligands/nm2), which is not surprising considering the low molecular weight (MW) of these ligands. The nanoparticles in aqueous solution were deposited directly on glass wool for the PHIP hydrogenation test (catalyst-1) or mixed with titanium oxide (TiO2) having 5-micron particles with 3.2 nm pores (Strem Chemicals) to obtain desirable loadings percentages (catalyst-2). The resulting mixture was deposited on a piece of glass wool. Dry samples of heterogeneous catalysts were obtained by drying under vacuum. The particles, either in pure form or supported on oxides, have very poor solubility with most common organic solvents or do not dissolve at all. Therefore, leaching is a problem only if copious amounts of water flow over it. This is not an issue in gas-phase reactions done in continuous flow mode or when used in multiple cycles. High temperature (if deliberately increased) can lead to excessive loss of ligands (as supported by our TGA results in SI) and can lead to ligand degradation and particle-particle coalescence. However, at low particle loadings (∼1% Pt on support) and at temperatures around 150–200°C, we did not observe any adverse effect on propane gas polarization.

The hydrogenation reactions were carried out inside the NMR tube containing the platinum catalyst under a continuous flow of propene and parahydrogen. The outlet pressures in both gas cylinders were regulated at 40 psi, and the flow rates were 30 ccm. We observed significant changes in PHIP efficiency when flow rates were changed. For example, the polarization efficiency decreased as the hydrogen flow was lowered from 30 ccm down to 5 ccm. The NMR tube was heated to 140°C in the NMR probe during reaction detection. NMR data for hydrogenation were acquired inside a standard 10 mm NMR tube by application of a 10 µs-long RF pulse (45°C flip angle), 500 ms acquisition time, and 300 ms pre-pulse delay. The NMR instrument used was a vertical-bore 9.4-T (400 MHz) Varian spectrometer.

Author Contributions

R.S. designed and performed experiments, R.S. and L.S.B. conducted data processing and error analysis, R.S. and L.S.B. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

R.S. and L.S.B. acknowledge Profs. Jeffrey Reimer, Neil Garg and Warren S. Warren for useful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to William Gelbart for stimulating discussions.

References

- Spiess H. W. NMR Spectroscopy: Pushing the Limits of Sensitivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 639–642 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T., Ramamoorthy A. & Webb G. A. How Far Can the Sensitivity of NMR Be Increased? in Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy, Vol. 58 155–175 (Academic Press, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Albert M. S. et al. Biological magnetic resonance imaging using laser-polarized 129Xe. Nature 370, 199–201 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. A. et al. Polarization-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy of Biomolecules in Frozen Solution. Science 276, 930–932 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire Y., Chuang I. L., Zhang S. & Gershenfeld N. Ultra-small-sample molecular structure detection using microslot waveguide nuclear spin resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9198–9203 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott R. et al. Liquid-State NMR and Scalar Couplings in Microtesla Magnetic Fields. Science 295, 2247–2249 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budker D. & Romalis M. Optical magnetometry. Nat. Phys. 3, 227–234 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Childress L. et al. Coherent Dynamics of Coupled Electron and Nuclear Spin Qubits in Diamond. Science 314, 281–285 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R. & Weitekamp D. P. Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical Reaction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2645–2648 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R. & Weitekamp D. P. Parahydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 5541–5542 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S. B. & Wood N. J. Parahydrogen-based NMR methods as a mechanistic probe in inorganic chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 2278–2291 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. W. et al. Reversible Interactions with para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science 323, 1708–1711 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M. J. et al. Iridium N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Magnetization Transfer from para-Hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6134–6137 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V., Beck I. E., Bukhtiyarov V. I. & Koptyug I. V. Observation of Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Hydrogenation on Supported Metal Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 1492–1495 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kovtunov K. V. & Koptyug I. V. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenations. in Magnetic Resonance Microscopy 99–115 (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard L. S. et al. NMR Imaging of Catalytic Hydrogenation in Microreactors with the Use of para-Hydrogen. Science 319, 442–445 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telkki V. V. et al. Microfluidic Gas-Flow Imaging Utilizing Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization and Remote-Detection NMR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 122, 8541–8544 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M., Johannesson H., Axelsson O. & Karlsson M. Hyperpolarization of 13C through order transfer from parahydrogen: A new contrast agent for MRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 23, 153–157 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E. et al. Perfusion assessment with bolus differentiation: A technique applicable to hyperpolarized tracers. Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 1043–1051 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar M. S. et al. Preparing High Purity Initial States for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Quantum Computing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 040501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard L. S. et al. Para-Hydrogen-Enhanced Hyperpolarized Gas-Phase Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 4064–4068 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkemeyer J., Haake M. & Bargon J. Hetero-NMR Enhancement via Parahydrogen Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 2927–2928 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Carravetta M. & Levitt M. H. Theory of long-lived nuclear spin states in solution nuclear magnetic resonance. I. Singlet states in low magnetic field. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 214505–214514 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptyug I. V. et al. para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5580–5586 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R. Encyclopedia of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Vol. 9 (ed. Harris, D.D.M.G.a.R.K.) 750–770 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, 2002).

- Khoobiar S. Particle to Particle Migration of Hydrogen Atoms on Platinum—Alumina Catalysts from Particle to Neighboring Particles. J. Phys. Chem. 68, 411–412 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Balu A. M., Duckett S. B. & Luque R. Para-hydrogen induced polarisation effects in liquid phase hydrogenations catalysed by supported metal nanoparticles. Dalton Trans., 5074–5076 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer P. S., Su X., Shen Y. R. & Somorjai G. A. Hydrogenation and Dehydrogenation of Propylene on Pt(111) Studied by Sum Frequency Generation from UHV to Atmospheric Pressure. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 16302–16309 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S., Roy D., Chaudhari R. V. & Sastry M. Pt and Pd Nanoparticles Immobilized on Amine-Functionalized Zeolite: Excellent Catalysts for Hydrogenation and Heck Reactions. Chem. Mater. 16, 3714–3724 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Adsorption study of 4-MBA on TiO2 nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 40, 2004–2008 (2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information