Abstract

The branching times of molecular phylogenies allow us to infer speciation and extinction dynamics even when fossils are absent. Troublingly, phylogenetic approaches usually return estimates of zero extinction, conflicting with fossil evidence. Phylogenies and fossils do agree, however, that there are often limits to diversity. Here, we present a general approach to evaluate the likelihood of a phylogeny under a model that accommodates diversity-dependence and extinction. We find, by likelihood maximization, that extinction is estimated most precisely if the rate of increase in the number of lineages in the phylogeny saturates towards the present or first decreases and then increases. We demonstrate the utility and limits of our approach by applying it to the phylogenies for two cases where a fossil record exists (Cetacea and Cenozoic macroperforate planktonic foraminifera) and to three radiations lacking fossil evidence (Dendroica, Plethodon and Heliconius). We propose that the diversity-dependence model with extinction be used as the standard model for macro-evolutionary dynamics because of its biological realism and flexibility.

Keywords: birth–death model, diversification, missing species

1. Introduction

The fossil record tells us that the fate of most species is to go extinct [1]. However, it tells an incomplete story, because most species leave no trace in the fossil record. Over the last two decades, molecular phylogenies of extant taxa have come to the fore as an additional source of information about diversification dynamics, and are especially valuable for clades with a poor fossil record [2,3]. Even though extinct species are necessarily absent from a molecular phylogeny of extant species, if per-lineage rates of speciation and extinction have been constant through time, extinction leaves a characteristic signature in the phylogenetic branching pattern, known as the pull-of-the-present [4,5]. On a lineages-through-time (LTT) plot—a semi-logarithmic plot with time before present on the x-axis and number of then-extant lineages with extant descendants on the y-axis—the pull-of-the-present is seen as a steepening of the slope of lineage accumulation towards the present. With the number of species-level molecular phylogenies exploding over the last decade, it has become apparent that very few show a pull-of-the-present. In fact, the opposite pattern is typical: the slope of lineage accumulation decreases towards the present, which leads to estimates of zero extinction [6–8]. Therefore, molecular phylogenies conflict with the fossil record regarding the importance of extinction, leading some to query the ability of phylogenies of extant taxa to deliver useful macro-evolutionary insights in isolation from fossil data [9].

Among the hypotheses put forward to explain the puzzle of not detecting extinction in molecular phylogenies are variation of diversification rates among lineages [10], a failure to recognize the youngest species [7] and relaxation of the assumption that speciation is instantaneous [11]. Another possible explanation is that speciation rates change through time [10,12], thereby erasing or concealing the signature of extinction. While the fossil record and molecular phylogenies provide conflicting estimates of extinction rate, both support the existence of a negative feedback of diversity on the diversification rates, termed diversity-dependence. Palaeontological evidence for diversity-dependence comes from the relatively constant diversity within numerous higher taxa over millions of years [13–18]. Molecular phylogenetic evidence lies in the abovementioned decreasing rate of branching through time for many clades, manifest as a levelling-off on a LTT plot [19–21].

If diversity-dependence and non-zero extinction are the rule, then models of diversification should include both processes. However, existing models that incorporate diversity-dependence assume extinction to be zero [22]. This is in part because simulations reveal that extinction erases the signature of a reduction in the speciation rate through time [23–25], leading to the suggestion that extinction rates have probably been low in clades that show a slowdown in branching rate [22,26]. An additional motivation for ignoring extinction has been expediency [27]: it is relatively simple to evaluate the likelihood of a diversity-dependent speciation model with no extinction (if there are no missing extant species), because such a model can be easily formulated in terms of a pure-birth model with a time-dependent speciation rate for which exact likelihood formulae exist [22]. With non-zero extinction, this mathematical simplification no longer holds because historical diversification rates depend on species that may have gone extinct and are therefore not observable in the phylogeny.

In this paper, we use a hidden Markov model (HMM) approach to numerically compute the likelihood of a phylogeny under a large variety of diversity-dependent birth–death models of diversification (see box 1 and electronic supplementary material for details). In contrast to previous approaches (for an exception, see [28]), our method also allows us to take into account incomplete sampling of species (which occurs for two out of the five case studies in this paper; table 2) and presence of other species that have gone extinct but affected diversification rates when the crown group began to radiate. Furthermore, it enables efficient computation of the distribution of both the number of ancestral lineages of extant species and the total historical diversity conditioned on the molecular phylogeny, at each time between the stem or crown age of the clade and the present. Both the likelihood and the distribution of the total historical diversity can incorporate fossil data. In this paper, we use fossil data to (i) identify plausible extinction rates and (ii) conduct an a posteriori test of the degree to which parameters estimated from phylogenies of extant species captures diversity through time.

Box 1. Computation of the likelihood under a diversity-dependent birth–death model.

We compute the likelihood of a phylogeny under a general diversity-dependent birth–death model, including the model of the main text. For a phylogeny with q extant species, we denote the branching times by tk so that t1 < t2 < …< tq−1, with present time tp > tq − 1 and crown age tc = tp − t1 (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Mathematically, the diversification process is described by the master equation. This is a dynamical equation for the probability Pn(t) of having n species at time t,

| B 1 |

The first two terms correspond to transitions increasing the probability Pn(t): an extinction event from n + 1 to n species (first term) or a speciation event from n − 1 to n species (second term). The last term corresponds to transitions decreasing the probability Pn(t): an extinction event from n to n − 1 species or a speciation event from n to n +1 species.

We modify the master equation (B1) to guarantee that the diversification process leads to the observed phylogeny. Consider a time t between the branching times tk − 1 and tk so that the phylogeny has k branches. Denote by Qn(t) the probability that a realization of the diversification process is consistent with the phylogeny up to time t and has n species at time t. The dynamical equation is

| B 2 |

The difference with the master equation (1) is in the first two terms. In the first term, we exclude extinction events in k species because none of the k branches in the phylogeny should become extinct. However, the species in these k branches can speciate. If that happens, either of the two daughter species can be included in the phylogeny, giving a factor 2k instead of k. Taken together with the speciation events in the n − k − 1 other species, we get the factor n + k − 1 of the second term in (B 2).

The following algorithm computes the probability of a phylogeny with q extant species:

— Initialize Qn(t) at the first branching time t1 with Qn(t1) = 1 for n = 2 and Qn(t1) = 0 otherwise.

- — For k =2, 3, …, q − 1 do

- (i) Integrate (B2) from tk − 1 to the next branching time tk.

- (ii) Multiply Qn(t) by k λn at the branching event at time tk.

— Integrate (B2) with k = q from tq − 1 to the present time tp.

— Extract component Qq(tp) from the probability vector Qn(t).

This is the likelihood unconditioned on survival of the two crown lineages. We use a similar approach to compute the probability that the two lineages initiated at branching time t1 have descendants at present time, tp. We define the likelihood as the probability of the phylogeny conditioned on the survival of the two lineages at t1. Our computational approach is quite flexible and can be extended to the computation of the number of species through time (figures 2g,h and 3j–l) or the inclusion of extant species missing in the phylogeny (as is the case for Cetacea and Heliconius; table 2). We refer to the electronic supplementary material for further details.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates and corresponding log-likelihood and Akaike weights for the CR birth–death model, the diversity-dependent model without extinction (DDL−E) and the diversity-dependent model with extinction (DDL+E). For the DDL+E model, intervals for the parameters are specified where the log-likelihood is 3 units smaller than the maximum value; when the log-likelihood never decreases 3 units, the lower or upper bound of the parameter is reported. This measure of uncertainty is more informative because it is less local than the confidence intervals based on the second derivatives of the likelihood at the likelihood optimum. For Cetacea, the results in bold correspond to the CR birth-death model (CRF), the diversity-dependent model (DDL+EF) and the ocean restructuring model (ORF), where in all three models, the extinction rate is set at the fossil estimate. The Akaike weights in bold correspond to comparison of these three models with one another. For ORF, there are two speciation rates (see text).

| dataset | Foraminifera | Cetacea | Dendroica | Plethodon | Heliconius | |||||||||||||

| clade age (Myr) | 64.95 | 35.86 | 5.00 | 11.3 | 16.76 | |||||||||||||

| clade size | 32 | 87 | 25 | 30 | 38 | |||||||||||||

| missing species | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| model | CR | DDL−E | DDL+E | CR | DDL−E | DDL+E | CRF | DDL+EF | ORF | CR | DDL−E | DDL+E | CR | DDL−E | DDL+E | CR | DDL−E | DDL+E |

| λ0 (Myr−1) | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.09 (0.45, 13.0) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.13; 0.22 | 0.29 | 1.05 | 3.04 (1.47, 6.13) | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.49 (0.30, 0.75) | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.40 (0.26, 0.58) |

| μ (Myr−1) | 0.05 | 0 | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 0 | 0 | 0.02(0, 0.06) | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 (0.06, 0.33) | 0 | 0 | 0.04 (0, 0.15) | 0 | 0 | 0.05 (0, 0.11) |

| K | ∝ | ∝ | 31.45 | ∝ | 355.7 | 227.6 | ∝ | 100.6 | ∝ | ∞ | 25.38 | 24.58 | ∝ | 35.89 | 32.96 | ∝ | 52.55 | 46.48 |

| K′ | ∝ | ∝ | 34.82 (32, 40.8) | ∝ | 355.7 | 263.4 (143.8, ∝) | ∝ | 175.77 | ∝ | ∝ | 25.38 | 26.00 (25, 30.1) | ∝ | 35.89 | 35.96 (30, 52.4) | ∝ | 52.91 | 52.37 (45.3, 68.5) |

| LL | −40.81 | −42.00 | −36.99 | 30.81 | 31.09 | 31.13 | 26.48 | 29.96 | 30.47 | 3.43 | 11.40 | 16.05 | −3.49 | −0.41 | −0.38 | 5.11 | 9.35 | 9.51 |

| Akaike weight | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.30 |

After introducing our model, we first study under what conditions precise inference can be made. Then, to illustrate our method, we apply a model with diversity-dependent speciation to two clades for which a fossil record exists and to three clades lacking a fossil record. The latter three clades are an arbitrary selection of well-sampled clades that have previously been subjected to high-profile studies on diversity-dependence, with our chief selection criterion being that we wanted to have representatives of a range of different taxa. We thus aimed to provide an unbiased outlook on the prospects for estimating extinction from phylogenies.

2. Material and methods

(a). Model

The diversity-dependent model that we consider is a straightforward extension of the constant-rate (CR) birth–death model [29], where the speciation rate depends linearly on the number of species, n, as in a logistic population growth model:

so that speciation and extinction rates equal each other at the ‘carrying capacity’ K, where λK = μK. This model is mathematically equivalent to a model with

under the substitution K′ = λ0K/(λ0 − μ). Here, K′ might be interpreted as the maximum number of niches that the species in the clade can occupy [30]. The parameter λ0 denotes the initial speciation rate (formally, when diversity is 0). This model (in either variant) is a generalization of the linear diversity-dependence (DDL) model without extinction in Rabosky & Lovette [22], and we therefore call it the DDL+E model, and we change the name of Rabosky and Lovette's model to DDL-E. We stress that our method to compute the likelihood is not limited to this model. It can be applied to other diversity-dependent models, for example, the generalization of the exponential diversity-dependence (DDX) model [22], or to models with diversity-dependent extinction rates. DDX speciation seems to be favoured in birds [2,22], while diversity-dependent extinction has received little empirical support from phylogenetic analyses [23,30] (but see [15]).

(b). Likelihood computation

When diversification rates are diversity-dependent, species other than those occurring in the phylogeny—namely the extinct and non-sampled species—also contribute to historical diversification rates (because the speciation rate is a function of the number of species in existence at each point in time). Despite their contribution to diversification dynamics, extinct and non-sampled species are hidden from observation. This situation requires the use of a HMM approach, because the system being modelled is a Markov process, but with unobserved states. In box 1, we outline how such an approach allows us to (numerically) compute the likelihood of a phylogeny under a wide variety of diversity-dependent birth–death models of diversification. See the electronic supplementary material for more details. Matlab code to implement the method (which is convertible to C or a stand-alone executable for Windows or Linux) is available from the corresponding author, and within the R package TreePar v. 2.2 [31] on CRAN (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/TreePar/index.html).

(c). Model fitting

We used Matlab's built-in optimization routine fminsearch to find the parameters that maximize the likelihood, choosing various initial conditions to minimize the risk of obtaining only a local maximum of the likelihood. The expected LTT plots and expected diversity through time conditional on the phylogeny were computed using the same mathematical procedures as for computing the likelihood itself. See the electronic supplementary material for details.

(d). Simulations

For a better understanding of the behaviour of the model, we plotted the expected number of lineages versus time (LTT) for various values of model parameters (λ0 = 0.8, K = 40, μ = 0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4) and crown ages (5, 10 and 15 Myr). The resulting 12 parameter combinations are sufficient to show the behaviour of the model: varying λ0 does not add a new dimension, because it is equivalent to rescaling time, the effect of which we already study by looking at different crown ages. In fact, the compound parameter of interest is the ratio of λ0 and μ, which we vary by changing μ. Varying K would mainly affect the time at which diversity-dependence becomes important, so it is mostly a matter of timescale as well. To assess the performance of our approach, we performed 100 simulations of the DDL+E model for each of the 12 parameter combinations and then estimated the maximum-likelihood parameters from the branching times. If the mean or median of a parameter estimated across these 100 simulations deviates significantly from the input value, this indicates bias. If the range of estimates is wide, this indicates low precision.

(e). Phylogenetic and fossil data

The foraminifera phylogeny was constructed exclusively from palaeontological data and includes all known Cenozoic species—extant and extinct—within the macroperforate clade [32]. Reconstruction of such a phylogeny is made possible by the unparalleled fossil record of this clade: a conservative estimate of the species-level completeness of the record is that on average, a species is recovered from over 80 per cent of the 1 Myr bins during its existence [15]. We used Aze et al.'s [32] phylogeny of evolutionary species, rather than one of morphospecies, to minimize the influence of pseudoextinction and pseudospeciation (anagenetic change of one morphospecies into another). We applied our method to the branching times of extant species only. We then simulated diversification under the estimated model parameters and compared the simulated diversity through time with the number of evolutionary lineages present at each time (including those that later go extinct).

The maximum clade credibility phylogeny of Cetacea includes 87 of 89 extant species, was based on sequence data for six mitochondrial DNA genes and nine nuclear genes and used palaeontological age constraints on several nodes [33]. We used Quental & Marshall's [9] estimates, based on fossil genera [34], of species diversity through time. Quental & Marshall gave both a liberal and conservative estimate of species diversity. The liberal estimate was obtained by counting the numbers of genera sampled in a particular time period, assuming that all genera present in each time period coexisted. The conservative estimate included only genera that crossed specific time-boundaries. In both cases, species diversity was extrapolated after correcting for the incompleteness of the fossil record at the genus level and the present day ratio of species to genera.

The maximum clade credibility molecular phylogeny of Dendroica warblers included all 25 continental species in the genus, including four species that were formerly placed in other genera [22]. The tree was scaled, such that the root was placed at 5 Myr [35]. For Plethodon, we restricted our focus to the chronogram of the glutinosus clade comprising 30 species [36]. The Heliconius butterfly molecular phylogeny included 38 of 44 species in the clade and branch lengths were estimated using a rate-smoothing local clock approach [37].

3. Results

(a). Bias and precision: simulations

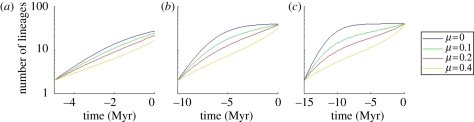

When clades are simulated over short timescales, extinction and diversity-dependence make little difference to the shape of LTT plots (figure 1a; though parameter estimates differ among the models). When the models are simulated for longer, however, the LTT plots have a remarkably different shape (figure 1b,c), either saturating to a plateau when extinction is low, or showing an inverted S-shape when extinction is higher. In the latter case, extinction causes the initial tendency to saturate to eventually be counteracted by the ‘pull-of-the-present’ [23,24].

Figure 1.

Lineages-through-time (LTT) plots under the diversity-dependent model for three different crown ages: (a) 5 Myr, (b) 10 Myr and (c) 15 Myr and four different extinction rates μ (0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 Myr−1). The speciation rate λ0 is 0.8 Myr−1 and the carrying capacity K equals 40. The pull-of-the-present is more pronounced for longer clade ages and higher extinction rates. Note that the LTT plots for shorter clade ages are not identical to the first part of the LTT plots for longer clade ages (except when there is no extinction).

We found that parameter estimates across simulated phylogenies were most biased and least precise for younger crown ages and higher extinction rates (table 1). Only when the data show a pattern similar to the curves in the rightmost panel of figure 1—either a clear pattern of saturation or a clear inverted S-shape—are the estimated parameters fairly reliable. Of our empirical datasets, only the foraminifera and Dendroica satisfy these criteria. Therefore, the maximum-likelihood parameter estimates for the other three groups should be interpreted with caution. Bias in parameter estimates (obtained by any method and not just maximum likelihood) particularly occurs for small sample sizes. The fact that the younger clades in our simulations generally have fewer species than older clades may therefore be responsible for the estimation bias we observe. The bias can here be understood by recognizing that, while a certain distribution of branching times may be a likely outcome under one set of parameters, the exact same pattern may be still more likely to arise under an altogether different combination of parameters (see electronic supplementary material for more details).

Table 1.

Bias and precision of the maximum-likelihood estimates, as shown by the median and the 25th and 75th percentiles of the estimated parameters of 100 simulated datasets.

| simulation parameters |

estimated parameters (25th, 50th, 75th percentiles) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ0 | K | crown age | μ | λ0 | μ | K |

| 0.8 | 40 | 5 | 0 | 1.21, 1.48, 1.77 | 0.02, 0.18, 0.45 | 24.54, 30.73, 34.74 |

| 0.1 | 1.28, 1.63, 2.35 | 0.19, 0.37, 0.55 | 20.68, 27.58, 33.58 | |||

| 0.2 | 1.37, 1.77, 3.25 | 0.31, 0.53, 0.82 | 18.58, 25.06, 30.26 | |||

| 0.4 | 1.63, 2.22, 3.53 | 0.42, 0.56, 0.90 | 14.63, 20.21, 25.51 | |||

| 10 | 0 | 0.80, 0.89, 1.03 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 39.39, 40.00, 40.00 | ||

| 0.1 | 0.70, 0.89, 1.15 | 0.06, 0.10, 0.13 | 38.55, 40.51, 41.81 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.78, 0.97, 1.20 | 0.15, 0.21, 0.28 | 35.69, 38.44, 42.00 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.97, 1.34, 1.82 | 0.36, 0.48, 0.61 | 29.18, 35.25, 41.08 | |||

| 15 | 0 | 0.79, 0.86, 0.97 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 39.64, 40.00, 40.00 | ||

| 0.1 | 0.72, 0.87, 1.13 | 0.08, 0.09, 0.12 | 37.79, 39.59, 40.82 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.71, 0.90, 1.15 | 0.16, 0.20, 0.23 | 37.37, 39.84, 43.40 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.88, 1.09, 1.46 | 0.32, 0.41, 0.52 | 32.62, 37.12, 41.05 | |||

(b). Case studies: phylogenies for clades with a fossil record

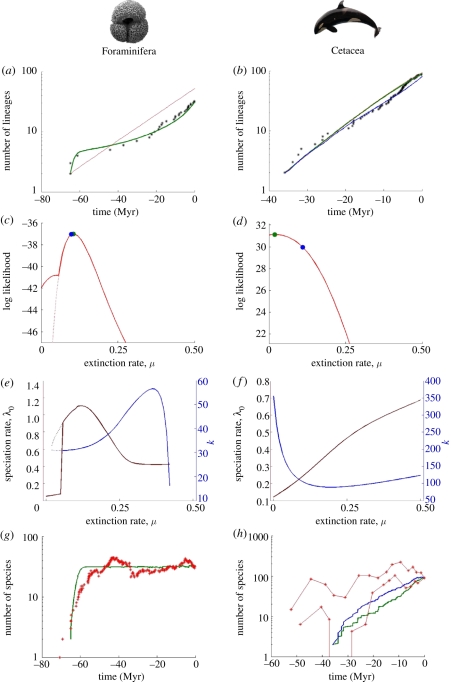

To illustrate the utility of our approach, we first consider the Cenozoic macroperforate planktonic foraminifera, which hold a unique position in the study of macroevolution, owing to the existence of both an excellent fossil record and complete phylogeny for evolutionary lineages [32]. We find that our model with diversity-dependent speciation plus diversity-independent extinction (DDL+E) provides an excellent fit to the inverted S-shaped LTT-plot for the phylogeny of extant species (figure 2a). Extinction rates are clearly non-zero (figure 2c,e and table 2) and very closely match estimates of μ = 0.0979 from the fossil record [15]. Moreover, the number of species through time predicted on the basis of the maximum-likelihood model parameters matches the fossil evidence reasonably closely (figure 2g). In contrast, although the CR birth–death model allows for non-zero extinction, it fits poorly, although better than a diversity-dependent model without extinction (table 2; [15]).

Figure 2.

Performance of our model for (a,c,e,g) Foraminifera and (b,d,f,h) Cetacea. (a,b) LTT plot (black stars) and prediction of the diversity-dependent model after likelihood maximization (green curve: DDL+E model; red curve: DDL−E (aka DDL) model; (b) the red and green curves are almost indistinguishable; blue curve is DDL+EF model). (c,d) Log-likelihood profile as a function of the extinction rate μ; the green dot indicates the maximum likelihood under DDL+E, and the blue dot the maximum likelihood for DDL+EF. The dotted lines denote an alternative local likelihood maximum. (e,f) Profiles of the maximum-likelihood estimates of the parameters λ0 and K as a function of the extinction rate μ. (g,h) The number of species through time as estimated from the fossil record (red stars for Foraminifera; red curves with stars for Cetacea denote lower and upper bounds [9]), and the prediction of this number is based on the molecular phylogeny only (green curve: DDL+E model; blue curve: DDL+EF model). We note that although the fits to the LTT plots are compelling, they are not entirely informative. This is because likelihood maximization searches for the parameters that make the observed branching times, the mode of the distribution of branching times, while the LTT plot displays the mean of this distribution for each point in time. The proper way to compare fits is to look at the likelihoods or Akaike weights (table 2).

Cetacea (whales and dolphins) provide a second case study for which both an almost complete molecular phylogeny [33] and estimates of genus diversity through time, based on the fossil record [9], are available. The Cetacean LTT plot is almost linear (figure 2b), meaning that the branching pattern will contain little information to distinguish among a wide range of diversification models (figure 1a). While our method identifies a maximum-likelihood extinction rate that is non-zero (table 2), it is substantially lower than an average genus extinction rate of 0.11 calculated using fossils [9]. Although estimates of fossil per-genus extinction rates do not necessarily translate directly to species extinction rates [38,39], the genus extinction rate may give a lower bound estimate of the species extinction rate [40]. Repeating the likelihood calculations with μ fixed at 0.11, we find that the likelihood of the diversity-dependent model (DDL+E) is only slightly lower (figure 2d) than when μ is free to vary and much higher than of the CR birth–death model. The clade is not fully saturated, as K = 227.6, whereas the number of extant species is 89. A recent study of Cetacean diversification based on phylogenetic information found evidence for elevated speciation rates during periods of ocean restructuring (between 35–31 and 13–4 Myr) [33]. With μ fixed at 0.11, we find the ocean restructuring (OR) model and DDL+E model to have a similar likelihood (table 2). In addition, the maximum-likelihood DDL+E parameters yielded a good agreement between the predicted historical diversity and that calculated from the fossil record of Cetacean genera [9] (figure 2h), demonstrating the benefits of combining fossil and phylogenetic data in terms of mutual illumination.

(c). Case studies: phylogenies for clades lacking a fossil record

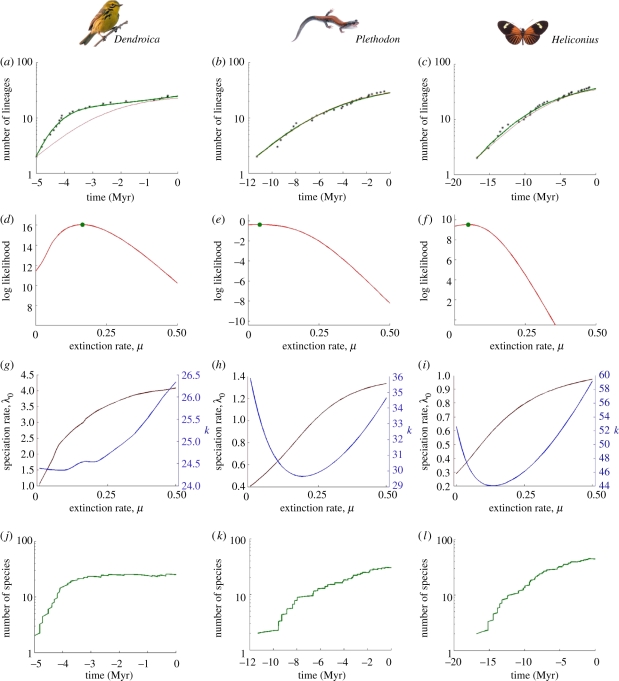

We now confront our model with the phylogenies for Dendroica warblers in North America [22], Plethodon salamanders in North America [36] and Heliconius butterflies in the Neotropics [37]. Each phylogeny represents a radiation of at least 20 species and is well-resolved, but each group lacks a fossil record. Dendroica and Heliconius are sometimes considered to be adaptive radiations, whereas Plethodon is sometimes referred to as a non-adaptive radiation, because many speciation events in this clade appear to have been ecologically equivalent geographical replacements [36]. All three phylogenies clearly show patterns of slowdowns in diversification rate towards the present [22,36,41].

For all three clades, likelihood maximization of the diversity-dependent model always leads to non-zero estimates of extinction (table 2). For Dendroica warblers, we find that the DDL+E model provides a substantially better fit to the LTT than a model without extinction (figure 3a and table 2). Under the maximum-likelihood DDL+E model, we predict that this clade reached its carrying capacity 4 Myr ago, after which the speciation and extinction rates have been in equilibrium (figure 3j). We note that the behaviour of our model is similar to Rabosky's [42] model of heritable extinction with pulsed turnover (HEPT), which also yielded a reasonable fit to the Dendroica LTT plot. Both our own and Rabosky's models find that warbler diversity has been constant over the last 4 Myr, with speciation and extinction in equilibrium throughout this period. However, the five-parameter HEPT model assumes that Dendroica diversity has been constant back to 5 Myr by modelling diversification as a Moran process, whereas our three-parameter model predicts it.

Figure 3.

Performance of our model for (a,d,g,j) Dendroica, (b,e,h,k) Plethodon and (c,f,i,l) Heliconius. (a–c) LTT plot (black stars) and prediction of the diversity-dependent model after likelihood maximization (green curve: DDL+E model; red curve: DDL−E model; (b,c) the red and green curves are almost indistinguishable). (d–f) Log-likelihood profile as a function of the extinction rate μ; the green dot indicates the maximum likelihood. (g–i) Profiles of the maximum-likelihood estimates of the parameters λ0 and K as a function of the extinction rate μ. (j–l) The number of species through time as predicted from the molecular phylogeny only.

The Plethodon and Heliconius phylogenies are also consistent with diversity-dependent speciation, with DDL+E and DDL−E models preferred to the CR model. In both cases, however, the DDL+E model has only marginally higher likelihood than the DDL−E model. In fact, the likelihood profiles for extinction are quite flat across a range of values (figure 3), even though the likelihood surfaces around the optimum are not so flat (errors in table 2): this means that the parameters are highly correlated.

4. Discussion

We have presented a new generalized likelihood-based inference method that allows estimation of extinction rates from the branching times of extant species when speciation is diversity-dependent. This has not previously been possible. The most precise estimation of extinction (and of the other parameters) occurs for LTT plots showing either saturation towards the present or an inverted S-shape (figure 1c and table 1), in which case we expect diversity to be equilibrating in the fossil record. For LTT plots of other shapes, phylogenies do not seem to contain sufficient information to distinguish between various models (figure 1a and table 1), and our predictions for historical diversity are less certain. Nevertheless, even in these cases, our approach brings us much closer to resolving the seeming inconsistency between fossil record and molecular phylogenies: diversity-dependence clearly allows for non-zero extinction rates, with the likelihood of the branching times comparable across a wide range of extinction rates. The Akaike weights of our five case studies indicate that the DDL+E outperforms the CR birth–death model in all case studies (for Cetacea when extinction was fixed at the fossil estimate) and the diversity-dependent model without extinction in the foraminifera and Dendroica (table 2).

The agreement between our phylogeny-based parameter estimates for foraminifera and those obtained by Ezard et al. [15], who used the complete fossil phylogeny, is encouraging. Both studies identify a diversity-dependent decline in speciation rate and estimate similar, non-zero, extinction rates. By using the whole tree of extinct as well a extant species, Ezard et al. [15] identified additional complexity in the diversification dynamics, including dependence of dynamics on species' ecology, an influence of the abiotic environment on diversification rates (particularly extinction) and some diversity-dependence in the extinction rates. Nonetheless, the fit of the three-parameter DDL+E model to the extant species phylogeny and the prediction of fossil diversity may be difficult to surpass using extant species data alone.

The Dendroica branching times are substantially more likely under the DDL+E model than either the DDL−E or CR models. Note that, while the topology we use for Dendroica is the same as in Rabosky & Lovette [22], our maximum-likelihood parameter estimates differ from theirs because we treat the root as 5 Myr, whereas they scale the tree so that the root-to-tip-length equals one. The DDL+E model (LL = 16.05) also outperforms the DDX (=DDX − E) model (LL = 13.45) and the SPVAR model (a model where speciation declines through time and extinction is constant, LL = 11.40), which performed best in earlier studies of Rabosky & Lovette [22,23], respectively. Our findings agree with earlier studies that this North American radiation was initially explosive and then slowed down [22,23,35], but our study differs from earlier studies, in that we estimate appreciable extinction rates and a much faster speciation rate at the crown of the tree than that of the DDL−E and SPVAR models (though not the DDX model).

While the foraminifera and Dendroica show an inverted S-shape or a plateau, respectively—in which cases parameter estimates are accurate (table 1)—Cetacea, Heliconius and Plethodon do not show these patterns. We therefore expect the parameter estimates to be uncertain and potentially subject to bias. Indeed, the likelihood surface is relatively flat across a wide range of extinction rates including zero (figure 3e,f) and the errors in the estimates are large (table 2). The Akaike weights of the DDL+E model are not the highest, but still appreciable. From a Bayesian perspective, if there were grounds to favour a low prior probability for zero extinction, the diversity-dependent model with extinction would always have outperformed its zero-extinction counterpart, as the posterior probability would recover the prior. However, identifying an appropriate prior distribution for extinction is not straightforward, particularly if extinction is phylogenetically clustered [42].

While our focus has been on modelling extinction (owing to the apparent conflict between phylogenetic estimates and fossil evidence in previous studies), we note that if diversification is indeed diversity-dependent then our approach will also provide more accurate estimates of other parameters of diversification. By the same token, if the likelihood surface for extinction is flat, estimates of speciation rates will be subject to similar uncertainty (table 2). We note that our parameter λ0 denotes only the initial speciation rate. The speciation rate rapidly decreases as diversity increases, and hence, in most cases (but not in Cetacea), the speciation rate at the present is similar in magnitude to the extinction rate. If we do not allow species other than those at the crown to exist and contribute to diversity-dependence at the present, a large initial speciation rate is required to make present speciation and extinction rates similar. As such, our method can also be used to detect the presence of other species at the crown age (see electronic supplementary material), but we have no evidence to suggest that multiple closely related competitors existed at the root of the radiations we consider here.

Various hypotheses other than diversity-dependence have been offered to explain macroevolutionary dynamics. In foraminifera, the changing climate appears to play a crucial role; for instance, it may explain the drop in diversity around 34 Myr ago [15]. Likewise, in Cetacea, there is evidence that restructuring of the oceans during the periods 35–31 and 13–4 Myr ago caused temporary increases in speciation rate [33]. We do not deny the influence of external factors on macroevolutionary dynamics, but these external drivers are idiographic [18] and will need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. In contrast, we argue that there is now ample and diverse evidence that diversity-dependence appears to be a general, nomothetic, phenomenon [18], if not ubiquitous [13–17,19–21] and has a pronounced effect on macroevolutionary dynamics. We suggest that the diversity-dependent model with extinction should be preferred to the CR birth–death or pure birth model as a more biologically realistic model for macroevolution. Although the CR birth(–death) model is a more appropriate null model from a statistical perspective because of its greater simplicity, we believe that the generality of diversity-dependence requires a more realistic null: models incorporating other (particularly idiographic) mechanisms should be assessed against the (nomothetic) model of diversity-dependence. Also the diversity-dependent model contains the CR birth and birth–death models as special cases; hence, parameter estimates can inform us whether diversity-dependence is strong or weak.

The MEDUSA method [43] has been developed to identify—on the basis of higher level phylogenies and the species richness of clades—the locations of rate transitions in temporally homogeneous constant speciation and extinction rates, with a CR birth–death model as the null. This method could be extended by introducing DDL+E as a more realistic null model and allowing for transitions in each of the three DDL+E parameters. There is no longer a computational obstacle to this use of the DDL+E model.

Diversity-dependence need not always be negative. As the clade diversifies, more niches can be constructed, either by external factors (climate), or owing to the mere presence of the species themselves [2,44]. In the former case, this can be incorporated in our framework by enlarging K. In the latter case, the constructed niches do not affect the diversity-dependence of the clade under consideration (e.g. arrival of predators [2]) or a key innovation has opened up new opportunities; this can be modelled as a decoupling of diversity-dependent dynamics of the innovative subclade from the main clade. This model is explored elsewhere [45].

While our method can estimate non-zero extinction, our estimates for Cetacea, Plethodon and Heliconius are low and likely to underestimate the true rate. This happens because most reconstructed phylogenies do not show the pull-of-the-present that is the signature of a high extinction rate [6,7]. When the fact that speciation is not instantaneous is incorporated in the CR birth–death model, the pull-of-the-present is diminished, disappears entirely or is even transformed into a concave curve, depending on the time taken for speciation to complete [11]. We conjecture that incorporating protracted speciation in the DDL+E model will result in higher extinction estimates. A likelihood formula is not yet available for protracted speciation in the CR model, let alone in the DDL+E model. Moreover, because our results (figure 1, table 1 and electronic supplementary material, figure S2) indicate that the branching patterns of real phylogenies are equally likely to arise under a wide range of models, the prospects for estimating parameters under other models, which are more complex still, are likely to be limited.

We have studied one of the simplest models of diversity-dependence. It may be viewed as a phenomenological description, similar to logistic growth in a population. However, it may also be interpreted more mechanistically, similar to colonization–extinction dynamics in a metapopulation [46]; the underlying assumptions are then that speciation can fill any one of the K′ niches with equal probability and that the ecological dynamics (population growth) of a newly arisen species are much faster than the evolutionary dynamics of diversification. This interpretation opens up a suite of mathematical tools and results of metapopulation ecology, for example, that the predictions for diversity are still good approximations even if species vary in their extinction rates owing to population size fluctuations [47]. Nevertheless, various other diversity-dependence models are possible, including ones that do not set a maximum to diversity (e.g. with an exponentially declining speciation rate with diversity). While the latter property seems preferable, it lacks a mechanistic underpinning. We hope that our work will stimulate research in this direction, as we have provided a framework in which computing the likelihood of the phylogenetic branching pattern associated with such models no longer presents a barrier.

Our analyses demonstrate both the potential and limitations of estimating separate speciation and extinction rates from molecular phylogenies. Although the absence of extinct lineages from molecular phylogenies implies that they provide an incomplete picture of macroevolutionary dynamics, we have shown that a more realistic model, which includes diversity-dependence and allows for non-zero extinction, returns parameter estimates that are not at odds with the fossil record. Thus, even when fossils are absent, molecular phylogenies can be an informative means of inferring past speciation and extinction dynamics.

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Barraclough, A. Humphreys, T. Quental, D. Rabosky and J. Rosindell for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript, T. Ezard, S. Ho, K. Kozak, J. Mallet, C. Marshall, T. Quental, D. Rabosky and M. Steeman for providing phylogenetic trees or fossil data, and M. Foote for advice. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments. The Heliconius and foram photos were provided by J. Mallet and H. Coxall, respectively; the other photos are under Public Domain license on Wikimedia Commons. We thank P. Etienne for photo editing. Financial support for R.S.E. was provided by a VIDI grant from the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO-ALW) and a FRoSpects Short Visit Grant from the European Science Foundation (ESF), for R.S.E. and B.H. by an exchange grant from the Van Gogh Programme, and for T.A. by NERC (grant NE/E015956/1 to A.P. and P.N.P.).

References

- 1.Raup D. M. 1986. Biological extinction in Earth history. Science 231, 1528–1533 10.1126/science.11542058 (doi:10.1126/science.11542058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nee S., Mooers A. O., Harvey P. H. 1992. Tempo and mode of evolution revealed from molecular phylogenies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8322–8326 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8322 (doi:10.1073/pnas.89.17.8322) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pybus O. G., Harvey P. H. 2000. Testing macro-evolutionary models using incomplete molecular phylogenies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 2267–2272 10.1098/rspb.2000.1278 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1278) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nee S., Holmes E. C., May R. M., Harvey P. H. 1994. Extinction rates can be estimated from molecular phylogenies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 344, 77–82 10.1098/rstb.1994.0054 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1994.0054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubo T., Iwasa Y. 1995. Inferring the rates of branching and extinction from molecular phylogenies. Evolution 49, 694–704 10.2307/2410323 (doi:10.2307/2410323) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nee S. 2006. Birth–death models in macroevolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 37, 1–17 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110035 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purvis A. 2008. Phylogenetic approaches to the study of extinction. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 39, 301–319 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.063008.102010 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.063008.102010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir J. T. 2006. Divergent timing and patterns of species accumulation in lowland and highland neotropical birds. Evolution 60, 842–855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quental T. B., Marshall C. R. 2010. Diversity dynamics: molecular phylogenies need the fossil record. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabosky D. L. 2010. Extinction rates should not be estimated from molecular phylogenies. Evolution 64, 1816–1824 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00926.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00926.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etienne R. S., Rosindell J. 2011. Prolonging the past counteracts the pull of the present: protracted speciation can explain observed slowdowns in diversification. Syst. Biol. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr091) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morlon H., Potts M. D., Plotkin J. B. 2010. Inferring the dynamics of diversification: a coalescent approach. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000493. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000493 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alroy J. 2010. The shifting balance of diversity among major marine animal groups. Science 329, 1191–1194 10.1126/science.1189910 (doi:10.1126/science.1189910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabosky D. L., Sorhannus U. 2009. Diversity dynamics of marine planktonic diatoms across the Cenozoic. Nature 457, 183–187 10.1038/nature07435 (doi:10.1038/nature07435) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ezard T. H. G., Aze T., Pearson P. N., Purvis A. 2011. Interplay between changing climate and species' ecology drives macroevolutionary dynamics. Science 332, 349–351 10.1126/science.1203060 (doi:10.1126/science.1203060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould S. J., Raup D. M., Sepkoski J. J., Schopf T. J. M., Simberloff D. S. 1977. The shape of evolution: a comparison of real and random clades. Paleobiology 3, 23–40 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanley S. M. 1973. Effects of competition on rates of evolution, with special references to bivalve mollusks and mammals. Syst. Zool. 22, 486–506 10.2307/2412955 (doi:10.2307/2412955) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raup D. M., Gould S. J., Schopf T. J. M., Simberloff D. S. 1973. Stochastic models of phylogeny and the evolution of diversity. J. Geol. 81, 525–542 10.1086/627905 (doi:10.1086/627905) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillimore A. B., Price T. D. 2008. Density-dependent cladogenesis in birds. PLoS Biol. 6, e71. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060071 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPeek M. A. 2008. The ecological dynamics of clade diversification and community assembly. Am. Nat. 172, E270–E284 10.1086/593137 (doi:10.1086/593137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabosky D. L., Glor R. E. 2010. Equilibrium speciation dynamics in a model adaptive radiation of island lizards. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22 178–22 183 10.1073/pnas.1007606107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1007606107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabosky D. L., Lovette I. J. 2008. Density-dependent diversification in North American wood warblers. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2363–2371 10.1098/rspb.2008.0630 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0630) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabosky D. L., Lovette I. J. 2008. Explosive evolutionary radiations: decreasing speciation or increasing extinction through time? Evolution 62, 1866–1875 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00409.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00409.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quental T. B., Marshall C. R. 2009. Extinction during evolutionary radiations: reconciling the fossil record with molecular phylogenies. Evolution 63, 3158–3167 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00794.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00794.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liow L. H., Quental T. B., Marshall C. R. 2010. When can decreasing diversification rates be detected with molecular phylogenies and the fossil record? Syst. Biol. 59, 646–659 10.1093/sysbio/syq052 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syq052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabosky D. L., Lovette I. J. 2009. Problems detecting density-dependent diversification on phylogenies: reply to Bokma. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 995–997 10.1098/rspb.2008.1584 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1584) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bokma F. 2009. Problems detecting density-dependent diversification on phylogenies. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 993–994 10.1098/rspb.2008.1249 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1249) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stadler T. 2009. On incomplete sampling under birth–death models and connections to the sampling-based coalescent. J. Theor. Biol. 261, 58–66 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.07.018 (doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.07.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nee S., May R. M., Harvey P. H. 1994. The reconstructed evolutionary process. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 344, 305–311 10.1098/rstb.1994.0068 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1994.0068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker T. D., Valentine J. W. 1984. Equilibrium models of evolutionary species diversity and the number of empty niches. Am. Nat. 124, 887–899 10.1086/284322 (doi:10.1086/284322) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stadler T. 2011. Mammalian phylogeny reveals recent diversification rate shifts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6187–6192 10.1073/pnas.1016876108 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1016876108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aze T., Ezard T. H. G., Purvis A., Stewart D., Coxall H. K., Wade B. S., Pearson P. N. 2011. A phylogeny of Cenozoic planktonic foraminifera from fossil data. Biol. Rev. (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00178.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steeman M. E., et al. 2009. Radiation of extant Cetaceans driven by restructuring of the oceans. Syst. Biol. 58, 573–585 10.1093/sysbio/syp060 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp060) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhen M., Pyenson N. D. 2007. Diversity estimates, biases, and historiographic effects: approaches to resolving Cetacean diversity in the tertiary. Palaeontol. Electron. 10, 11A:22p [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovette I. J., Bermingham E. 1999. Explosive speciation in the New World Dendroica warblers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 1629–1636 10.1098/rspb.1999.0825 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0825) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozak K. H., Weisrock D. W., Larson A. 2006. Rapid lineage accumulation in a non-adaptive radiation: phylogenetic analysis of diversification rates in eastern North American woodland salamanders (Plethodontidae: Plethodon). Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 539–546 10.1098/rspb.2005.3326 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3326) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallet J., Beltrán M., Neukirchen W., Linares M. 2007. Natural hybridization in heliconiine butterflies: the species boundary as a continuum. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 28. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-28 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-28) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janevski G. A., Baumiller T. K. 2009. Evidence for extinction selectivity throughout the marine invertebrate fossil record. Paleobiology 35, 553–564 10.1666/0094-8373-35.4.553 (doi:10.1666/0094-8373-35.4.553) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leighton L. R., Schneider C. L. 2008. Taxon characteristics that promote survivorship through the Permian–Triassic interval: transition from the Paleozoic to the Mesozoic brachiopod fauna. Paleobiology 34, 65–79 10.1666/06082.1 (doi:10.1666/06082.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raup D. M. 1985. Mathematical models of cladogenesis. Paleobiology 11, 42–52 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fordyce J. A. 2010. Host shifts and evolutionary radiations of butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 3735–3743 10.1098/rspb.2010.0211 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0211) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabosky D. L. 2009. Heritability of extinction rates links diversification patterns in molecular phylogenies and fossils. Syst. Biol. 58, 629–640 10.1093/sysbio/syp069 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alfaro M. E., Santini F., Brock C., Alamillo H., Dornburg A., Rabosky D. L., Carnevale G., Harmon L. J. 2009. Nine exceptional radiations plus high turnover explain species diversity in jawed vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13 410–13 414 10.1073/pnas.0811087106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0811087106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odling-Smee F. J., Laland K. N., Feldman M. W. 2003. Niche construction: the neglected process in evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 45.Etienne R. S., Haegeman B. In preparation Detecting key innovations in phylogenies of extant species. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levins R. 1970. Extinction. In Some mathematical problems in biology (ed. Gerstenhaber M.), pp. 77–107 Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etienne R. S. 2000. Local populations of different sizes, mechanistic rescue effect and patch preference in the Levins metapopulation model. Bull. Math. Biol. 62, 943–958 10.1006/bulm.2000.0186 (doi:10.1006/bulm.2000.0186) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]