Abstract

For more than 60 years, the mood stabilizer lithium has been used alone or in combination for the treatment of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression, and other mental illnesses. Despite this long history, the molecular mechanisms trough which lithium regulates behavior are still poorly understood. Among several targets, lithium has been shown to directly inhibit glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha and beta (GSK3α and GSK3β). However in vivo, lithium also inhibits GSK3 by regulating other mechanisms like the formation of a signaling complex comprised of beta-arrestin 2 (βArr2) and Akt. Here, we provide an overview of in vivo evidence supporting a role for inhibition of GSK3 in some behavioral effects of lithium. We also explore how regulation of GSK3 by lithium within a signaling network involving several molecular targets and cell surface receptors [e.g., G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs)] may provide cues to its relative pharmacological selectivity and its effects on disease mechanisms. A better understanding of these intricate actions of lithium at a systems level may allow the rational development of better mood stabilizer drugs with enhanced selectivity, efficacy, and lesser side effects.

Keywords: lithium, glycogen synthase kinase 3, arrestin, Akt, mood stabilizer, bipolar disorder, pharmacology, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

Lithium is an alkali metal that is used medically under the form of a cationic salt Li+ in association with carbonate (COO−) or citrate. Lithium salts have been used medically since the late nineteenth century for instance as part of popular tonics such as the “Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda” better known under the name of 7UP (Williams and Harwood, 2005). The first publication on the use of lithium to treat acute mania was published by John Cade more than 60 years ago (Cade, 1949). However, it took 22 years for the U.S. food and Drug administration to approve lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Over time, lithium has become a gold standard for the management of bipolar mood disorders and cyclothymia. Each of these mental illnesses affects 1–2% of the population and is characterized by alternating episodes of manic and depressive symptoms (Cade, 1949; Schou et al., 1954; Blanco et al., 2002). Lithium has been reported to reduce suicide rates and prevent manic episodes in individuals with bipolar disorder, major depression, or schizoaffective disorders (Bowden, 2000; Cipriani et al., 2005; Muller-Oerlinghausen et al., 2005; Tondo and Baldessarini, 2009). Lithium is also used as part of combination therapies for augmenting the effects of other psychoactive drugs such as antidepressants and antipsychotics affecting monoaminergic neurotransmission (De Montigny et al., 1981; Valenstein et al., 2006).

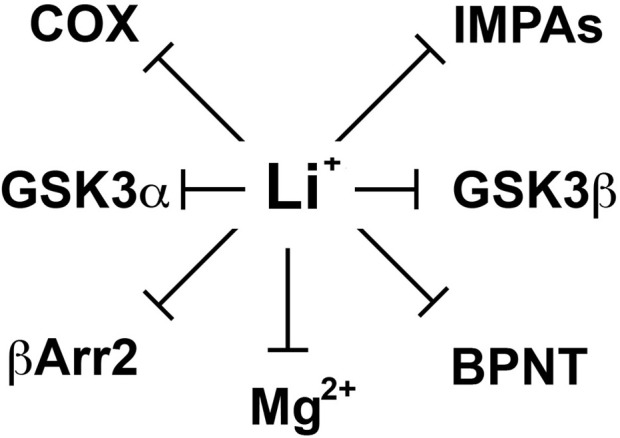

Despite important clinical applications, the molecular mechanisms by which lithium exerts its therapeutic effects in mental disorders are still not well understood (Phiel and Klein, 2001; Beaulieu and Caron, 2008). Over the years, lithium has been shown to inhibit various enzymes directly in vitro (Figure 1). These include inositol monophosphatases (IMPAs) (Berridge et al., 1989), bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase (BPNT1) (Spiegelberg et al., 2005), cyclooxygenase (COX) (Rapoport and Bosetti, 2002) and isoforms of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) (Klein and Melton, 1996; Stambolic et al., 1996; Phiel and Klein, 2001). Studies conducted using different cellular models or organisms (e.g., Mus. musculus, Caenorhabditis elegans or Dictyostelium discoideum) have documented the importance of these effects of lithium on different physiological or pathological processes including development and epilepsy (Klein and Melton, 1996; Williams et al., 2002; Shaldubina et al., 2006; Cryns et al., 2007, 2008). However, the relative involvement of these direct molecular targets of lithium in behavioral effects that would be clinically relevant to depression or mania has often not been demonstrated. Furthermore, it is also unclear how the action of lithium on ubiquitously expressed molecules that are mostly involved in the regulation of cell signaling and not to specific neurotransmitter systems can explain its relative selectivity as a therapeutic agent in psychiatry.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of different direct molecular targets of lithium. These include inositol monophosphatases (IMPAs), Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase (BPNT), cyclooxygenase (COX), beta-arrestin 2 (βArr2), and members of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha and beta (GSK3α and β). Since the mechanism by which lithium would inhibit several of these molecules is by competing with magnesium ions (Mg2+) acting as a co-factor we also included the possibility that other molecular targets may be affected through such competition.

Here we provide an overview of several independent line of evidence suggesting that lithium can exert “anti-manic” and “antidepressant” like effects by affecting the activity of GSK3α and β both as a direct inhibitor and as a modulator of cell signaling pathways regulating the activity of these kinases. We also speculate on the possible importance of such intricate regulation mechanisms for lithium efficacy in several types of combination therapies and for its relative clinical selectivity.

The regulation of GSK3 signaling by Akt and cell surface receptors

The GSK3 family of serine threonine kinases is composed of two isoenzymes/paralogous proteins GSK3α and GSK3β, which were originally identified for their role in insulin receptors signaling (Embi et al., 1980; Parker et al., 1983; Woodgett, 1990; Cross et al., 1995). Since then, the biological roles of these kinases have been demonstrated to be much broader, including implications in the regulation of development, immunity/inflammation, cancer, neurotransmission, and several other biological processes (Cohen and Frame, 2001; Woodgett, 2001; Kaidanovich-Beilin and Woodgett, 2011). GSK3 is constitutively active in cells under resting/unstimulated conditions (Sutherland et al., 1993; Stambolic and Woodgett, 1994) and is primarily regulated through inhibition of its activity either by phosphorylation or the regulation of its incorporation into protein complexes. For instance activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling regulates GSK3 by increasing its phosphorylation on negative regulatory serine residues (Sutherland et al., 1993; Stambolic and Woodgett, 1994; Sutherland and Cohen, 1994; Cross et al., 1995). In contrasts, activation of canonical Wnt signaling prevents the action of GSK3 on βcatenin by preventing the formation of a protein complex involving adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and axin that targets active GSK3 to βcatenin (Behrens et al., 1998; Kishida et al., 1998).

The activity of GSK3α/β is positively regulated by phosphorylation on tyrosine residues (Thy 279 for GSK3α and Thy 216 for GSK3β) (Hughes et al., 1993; Lochhead et al., 2006) and negatively regulated by serine phosphorylation (Ser 21 for GSK3α and Ser 9 for GSK3β) that are situated in the N-terminal domains of these kinases (Sutherland et al., 1993; Stambolic and Woodgett, 1994; Sutherland and Cohen, 1994; Cross et al., 1995). While several serine/threonine kinases can phosphorylate these domains, the most prevalent negative regulators of GSK3 are members of a small family of kinases termed Akt. In mammals, this family is composed of three isoforms (Akt1, 2, and 3) that are themselves regulated by PI3K signaling that leads to an activatory phosphorylation of two residues (Alessi and Cohen, 1998). The Thr 308 residue of Akt1 is phosphorylated by phosphatidyl-dependant kinases, PDK1 and the Ser 473 residue is phosphorylated by the PDK2/rictor-mTOR, in response to PI3K signaling (Scheid and Woodgett, 2001; Jacinto et al., 2006). Of these two phosphorylation events, phosphorylation of Akt on Thr 308 has been shown to be essential and sufficient for the regulation of GSK3 by Akt (Jacinto et al., 2006). Over the years, myriads of cell surface receptors including several G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and most receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) have been shown to be involved in the activation of Akt isoforms via PI3K mediated signaling (Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010; Liao and Hung, 2010; Beaulieu, 2011; Swift et al., 2011).

In addition to these kinase-mediated mechanisms, phosphatases are also playing a role in the regulation of Akt and GSK3 activity. For instance, the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) is known to dephosphorylate the N-terminal serine residues of GSK3, therefore leading to its activation (Zhang et al., 2003). The protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) has also been shown to participate in the inhibition of Akt (Beaulieu et al., 2005). Importantly, there is evidence for a regulation of Akt activity by PP2A in response to GPCR stimulation. Activation of the dopamine receptor 2 (D2R) has been shown to stimulate the inactivation of Akt by PP2A (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011), therefore providing a mechanism through which GPCR activation can inhibit Akt in response to extracellular signals.

As a general mechanism, activation of GPCR leads to the activation of their cognate G proteins, which is rapidly followed by homologous receptor desensitization. This latter process involves the phosphorylation of the GPCR by GPCR kinases and the recruitment of the adaptor proteins β-arrestin 1 and β-arrestin 2 (βArr2) (Lohse et al., 1990; Ferguson et al., 1996). The recruitment of β-arrestins to GPCR leads to an uncoupling of the G protein and to clathrin mediated receptor internalization. However, β-arrestins can also participate to GPCR signaling by acting as molecular scaffolds for signaling molecules such as kinases and phosphatases (Luttrell et al., 1999; Luttrell and Gesty-Palmer, 2010). In the specific case of D2R, activation of the receptor by dopamine promotes the formation of a signaling complex composed of Akt, βArr2, and PP2A, which favor the dephosphorylation of Akt on Thr 308 and Akt inactivation. This in turn results in an activation of GSK3 by dopamine (Beaulieu et al., 2004, 2005). This mechanism of D2R signaling appears to play important roles in the regulation of locomotor behavior and sensory motor gating by dopamine (Beaulieu et al., 2004; Emamian et al., 2004). It could also contribute to the therapeutic and/or adverse effects of psychoactive drugs like amphetamines and antpsychotics that act on dopamine neurotransmission (Emamian et al., 2004; Masri et al., 2008; Beaulieu et al., 2009).

Direct and indirect regulation of GSK3 by lithium

In 1996, two independent studies (Klein and Melton, 1996; Stambolic et al., 1996) of the effects of lithium on cell signaling and development have identified a direct effect of lithium on the activity of GSK3 both in vitro and in cells. However, the therapeutic relevance of this finding has been unclear mostly because the high Ki values of lithium for GSK3α (∼3.5 mM) and GSK3β (∼2.0 mM) are superior to therapeutic lithium serum concentrations in humans (0.5–1.2 mM) (Phiel and Klein, 2001; Gould et al., 2004; Beaulieu and Caron, 2008; Beaulieu et al., 2008). However, these values can be affected by experimental conditions including the availability of Mg2+ ions in the assay system. Indeed, one hypothesis explaining the inhibition of GSK3 by lithium is that Li+ ions act as uncompetitive inhibitors for the binding of the co-factor magnesium to GSK3 (Ryves and Harwood, 2001). Magnesium and lithium share similar ionic radii (0.072 and 0.076 nm, respectively) and it has been suggested long ago (Birch, 1974) that this may explain several of the biochemical effects of lithium since Mg2+ is a cofactor for multiple enzymes (Figure 1). The proposed competitive mechanism of inhibition by lithium predicts that the in vivo inhibition of GSK3 may be greater than inhibition levels observed in vitro at optimal concentrations of magnesium ions (Ryves and Harwood, 2001).

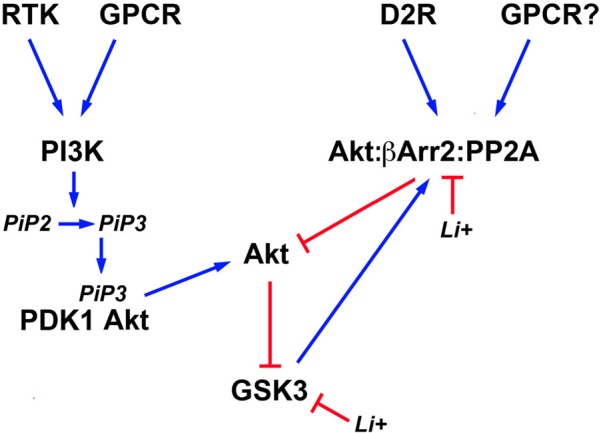

In addition to direct inhibition, lithium can also affect both isoforms of GSK3 indirectly by activating Akt (Figure 2). This results in an increased phosphorylation/inactivation of these kinases by Akt in cultured neurons (Chalecka-Franaszek and Chuang, 1999). A similar activation of Akt by lithium has also been found in the striatum, frontal cortex, and hippocampus of rodents following either acute or chronic treatment with lithium under conditions resulting in lithium brain concentrations that are compatible with therapeutic serum concentrations in humans (De Sarno et al., 2002; Beaulieu et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of signaling pathways regulating the activity of brain GSK3 and its regulation by lithium. Activation of different cell surface receptors activates Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K) that in turn phosphorylates Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3). Availability of PIP3 causes the co-recruitment of the 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and Akt to the cell membrane and the activation of Akt by PDK1. Phosphorylation of N-terminal serine residues of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) isoforms by activated Akt results in GSK3 inactivation. Conversely, activation of the D2 dopamine receptor (D2R) and potentially of other G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) triggers the formation of a signaling complex composed of Akt, beta-arrestin 2 (βArr2), and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) that results in an inactivation of Akt and concomitant relived GSK3 inhibition. Lithium can affect the equilibrium of this signaling network by inhibiting GSK3 directly and by disrupting the assembly of the Akt;βArr2;PP2A signaling complex. In addition, activated GSK3 would contribute to its own regulation by Akt by stabilizing the formation of this same protein complex.

The activation of Akt by lithium is explained in part by an effect of lithium on the regulation of Akt by βArr2 and the D2R. Co-immunoprecipitation studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo, have shown that the Akt:βArr2:PP2A signaling complex can be dissociated in response to therapeutically relevant lithium concentrations, thus providing a mechanism for the activation of Akt by lithium (Beaulieu et al., 2008). In support to this, both chronic and acute lithium treatment failed to activate Akt and increase GSK3 phosphorylation in mice lacking βArr2, in which the Akt:βArr2:PP2A signaling complex cannot be formed (Beaulieu et al., 2008). Furthermore, lithium also failed to regulate GSK3 phosphorylation in mice with reduced Akt1 activity (Pan et al., 2011). The exact detailed mechanism through which lithium interferes with the formation of the Akt;βArr2;PP2A signaling complex is only partially understood. In vitro experiments with recombinant purified Akt1 and βArr2 suggest that the interactions of these two proteins and thus complex formation, requires magnesium (Beaulieu et al., 2008). Therefore, competition between lithium and magnesium could underlie the instability of the Akt;βArr2;PP2A signaling complex in the presence of lithium (Birch, 1974; Beaulieu et al., 2008).

The direct inhibition of GSK3 by lithium also appears to contribute to the activation of Akt (Figure 2). Early experiments conducted in cells have suggested that GSK3 may promote its own activation by preventing the activation of Akt (Zhang et al., 2003). GSK3β has also been shown to interact with βArr2 (Beaulieu et al., 2005). Experiments conducted using transgenic mice over-expressing frog GSK3β in neurons, suggest the existence of a feed forward mechanism by which GSK3 promotes its own activation by stabilizing the Akt;βArr2;PP2A signaling complex (O'Brien et al., 2011). According to this model, direct inhibition of GSK3 would constitute an additional mechanism that can promote the disassembly of the Akt;βArr2;PP2A signaling complex in response to lithium. Interestingly, such feedback effects resulting from GSK3 inhibition may also contribute to strengthen the effects of lithium under other conditions. For instance there is evidence that GSK3 can regulate its own activation by phosphorylation of the Thy 279/Thy 216 residues (Lochhead et al., 2006). In addition, GSK3 can dampen PI3K signaling by destabilizing the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) protein that contributes to PI3K and Akt activation downstream of the insulin receptor (Eldar-Finkelman and Krebs, 1997; Liberman et al., 2008; Waraich et al., 2008). Therefore, it would be interesting to examine how such effects of GSK3 inhibition at the level of signaling networks can contribute to the amplification and maintenance of the effects of lithium in different cell types or organs.

Evidence for a role of Akt and GSK3 signaling in the behavioral effects of lithium

To our knowledge, there is no human study implicating GSK3 or any of the other potential molecular targets of lithium in its therapeutic effects. Furthermore, research has been hindered by a lack of a good animal model of bipolar disorder with construct validity. However, behavioral tests with predictive validity for antimanic or antidepressant drug effects have been used extensively. Interestingly, inhibition of GSK3 activity seems to replicate both the “antidepressant” and “antimanic” like effects of these drugs in rat and mice, at least in some genetic backgrounds (Beaulieu et al., 2004, 2008; Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2004; O'Brien et al., 2004; Mines et al., 2010).

While reduction of GSK3 activity does replicate several behavioral effects of lithium it remains improbable that direct inhibition of GSK3 by lithium solely explains its effects on behavior. One major reason for this is that lithium concentrations in excess of therapeutic concentrations are often necessary to inhibit GSK3 in cell based assays (Kremer et al., 2011). Furthermore, molecules acting upstream of GSK3 also appear to be essential for the behavioral effects of lithium. Indeed, βArr2-KO mice, in which lithium does not affect the phosphorylation of Akt (Thr 308) and GSK3β (Ser 9), have been shown not to respond behaviorally to either chronic or acute lithium treatment (Beaulieu et al., 2008). Similarly, a recent study conducted on different strains of inbred mice has shown that lithium fails to affect the phosphorylation of Thr 308 Akt in DBA/2J mice (Pan et al., 2011). This lack of an effect of lithium on Akt phosphorylation was accompanied by a lack of antimanic and antidepressant like behavioral responses to lithium in these mice. Importantly, increased expression of Akt1 using a herpes simplex (HSV) viral vectors in the brain of DBA/2J mice restored lithium sensitivity (Pan et al., 2011). Therefore, not only βArr2 but also Akt1 would be necessary for the regulation of GSK3β Ser 9 phosphorylation and behavior by lithium. However, the effects of lithium have not been tested in these behavioral paradigms in mice lacking a functional Akt1 gene and it remains possible that the effects observed in DBA/2J mice might be associated to other characteristics of this genetic background.

The overall picture emerging from several studies of the role of GSK3 in the effects of lithium suggests a contribution of this kinase to at least some of its actions on behavior. However, this is based mostly on studies conducted with rodents using tests that were developed to predict the “antimanic” or “antidepressant” like effects of drugs. In the absence of a better understanding of the etiology of bipolar disorder, it may be more difficult to establish the exact contribution of GSK3 inhibition to the treatment of this psychiatric condition. That being said, a convergence of pharmacological and genetic evidences also supports the role of GSK3 in mood regulation as well as in the action of several drugs used for the management of psychiatric illnesses (Beaulieu et al., 2011; Jope, 2011). In this context, a contribution of GSK3 inhibition to the clinical effects of lithium provides a working model that may explain its relative clinical selectivity as well as its efficacy as an augmentation agent for other psychoactive drugs.

Convergence of actions, multiple hits, and target selectivity

The Akt1/GSK3 pathway sits at a convergence of several signaling mechanisms that have been associated to mental disorders (Figure 1). Among those, partial loss of function mutations in the genes encoding cognate ligands for the RTKs tropomyosin-receptor-kinaseB (TrkB) and epidermal growth factor receptor family 4 (ErbB-4) have been associated with enhanced risk for bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia (Neves-Pereira et al., 2002; Law et al., 2007; Jaaro-Peled et al., 2009; Schmidt and Duman, 2010). By reducing the activation of PI3K signaling, such genetic variation should result in a reduction in the activity of Akt and increased GSK3 activation. Similarly, genetic variation affecting the well-established negative regulator of GSK3—Akt1— and of potential negative GSK3 regulator—disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (Disc1)—have also been associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Emamian et al., 2004; Chubb et al., 2008; Kvajo et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2009). This suggests that several genetic risk factors for mental illnesses could lead to an increase in brain GSK3 activity. In contrast, lithium, antidepressant, and several antipsychotics have been shown to increase the inhibitory N-terminal phosphorylation of brain GSK3 in rodents (Beaulieu et al., 2004, 2009; Emamian et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004). Taken together, these observations suggest that inhibition of GSK3 is a plausible model for the action of lithium that may allow to reconcile its therapeutic effects with disease etiology, at least in some patient populations. Furthermore, this model predicts that lithium and several other psychoactive drugs may have an additive effect on GSK3 by inhibiting its activity trough different mechanisms that would complement and/or facilitate each other. Such a “multiple hit” inhibition of GSK3 by several drugs acting through different mechanisms may be one of the reasons underlining their mutual reinforcing effects in the clinic.

Interestingly, lithium also appears to inhibit GSK3 in vivo through a combination of mechanisms including its direct and indirect inhibition following Akt activation (Figure 2). This second type of inactivation mechanism would involve the disruption of a protein complex that is held together by βArr2 and stabilized by GSK3 (Beaulieu et al., 2008; O'Brien et al., 2011). While the direct inhibition of GSK3 by lithium is a relatively simple general mode of action that can affect all cells, its inhibition by an Akt/βArr2 dependent mechanism points toward the possibility that lithium may inhibit GSK3 with varying levels of efficacy in different cellular/neuronal populations. Indeed, the formation of βArr2 signaling complexes is dependent upon the activation of GPCRs (Luttrell et al., 1999) and such complex would only exist in cells that express the specific receptors (e.g., the D2R) that are responsible for their formation. By disrupting a βArr2 signaling complex that is responsible for the inhibition of Akt, lithium may, therefore, have a stronger effect on GSK3 activity in cells in which this complex is formed. In this case, targeting this complex may confer some level of selectivity, which may explain why lithium can be useful in the treatment of bipolar disorders without significantly disrupting GSK3 mediated physiological functions in the whole organism.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Lithium's mechanism of therapeutic action remains a mystery, more than 60 years after its first use for the treatment of mania in a clinical context. This situation has seriously prevented the development of improved pharmacotherapies for bipolar disorder. Some of the data reported in this review indicate that inhibition of GSK3 either directly or—more possibly—indirectly is a credible mechanism that may be responsible for some of lithium's actions. However, this remains not solidly established and several additional studies will be needed to clarify the exact contribution of GSK3 inhibition in lithium therapy.

A first important question is the role played by GSK3 inhibition in the effects of lithium in humans. Studies conducted over the past decade have relied mostly on studies conducted in vertebrates. While this approach is powerful and allows for a comparison between molecular and behavioral effects of lithium, it nevertheless remains analogical and correlative. Most of the behavioral tests used in animals have good predictive validity for a first evaluation of antimanic or antidepressant like drug effects (Crawley, 2008). However, these tests certainly do not reflect the complex and variable symptoms of bipolar disorder in humans. A logical next step of investigation could be to combine studies of drug responsiveness in human subjects with different genetic risk factors that can affect GSK3 activity. In this regard, recent studies have shown a possible association between a GSK3β promoter polymorphism and responsiveness to lithium (Benedetti et al., 2004; Adli et al., 2007; Serretti et al., 2008). However to be truly convincing such studies should be replicated across independent laboratories and expended to several risk factors.

The study of GSK3's involvement in humans would also be facilitated by the development of surrogate biomarkers for central nervous system GSK3 activity. The development of such markers would allow monitoring the activity of GSK3 in patients in correlation with disease states and responsiveness to treatment. In line with this, a study has shown that GSK3β phosphorylation in peripheral blood cells can be used as an indicator of responsiveness to treatment (Li et al., 2007). However, this approach has several limitations as it remains biochemical and not functional. Future investigations may add to this by establishing correlates between brain GSK3 activity and, for instance, physiological/electrophysiological response in peripheral tissue or changes in brain activity/physiology that can be monitored by magnetic resonance imaging (Blasi et al., 2011).

In addition to human studies, investigations in mammals can be expanded to address several questions in rodents and eventually non-human primates. Among questions that can be addressed in this way is the identification of molecular targets that are responsible for the impact of GSK3 activity on behavior. Furthermore, it would be important to establish neuroanatomical correlates of GSK3 activity and behavioral regulation. Finally, animal models probably remain the most powerful tool at our disposal to understand how lithium acts not on a single molecular target but on several interconnected cellular signaling networks to produce its therapeutic actions. For instance, the action of lithium on both GSK3 and a βArr2 signaling complex that regulates and is regulated by GSK3 suggests that lithium may affect GSK3 activity differently in cells that express this signaling complex. To our knowledge, only the D2R has been shown to trigger the formation of this complex. This is interesting as this receptor is also a major pharmacological target of antipsychotics (Snyder, 1976; Roth et al., 2004). The relevance of this to the therapeutic selectivity of lithium and its combined action with antipsychotics can be further explored by identifying the complement of GPCRs that are responsible for the formation of this complex and the impact of these receptors on lithium actions in vivo. Similarly, lithium does not only affect GSK3 activity but has several other molecular targets that are also involved in cell signaling (Gould and Manji, 2002; Beaulieu and Caron, 2008). It would thus be of interest to use animal models to explore the possible involvement of modulations of cell signaling landscape involving several of these targets in the overall behavioral effects of lithium. Such an approach may reveal unexpected and important new information that would not be obtainable using a research program aimed at identifying a single molecular target while excluding all others.

Overall, recent studies of the involvement of GSK3 in the action of lithium have established a strong correlation between GSK3 activity and the regulation of behavior. They have also indicated that lithium is regulating GSK3 not only directly but also through more complex network effects affecting more than one molecular target at a time. In the near future, a continuation of these studies in animal models and the establishment of strong associations with human data may allow furthering this knowledge. This could lead to the development of an understanding of the role of GSK3 as well as that of other molecular targets of lithium in its relatively specific effects on several mental illnesses. Such knowledge may be the key to the development of new, safer mood stabilizers having better efficacy and fewer side effects.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Psychiatry and a Team grant from the Fond du Québec-Nature et Technologie (FQRNT) to Jean-Martin Beaulieu.

References

- Adli M., Hollinde D. L., Stamm T., Wiethoff K., Tsahuridu M., Kirchheiner J., Heinz A., Bauer M. (2007). Response to lithium augmentation in depression is associated with the glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta -50T/C single nucleotide polymorphism. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 1295–1302 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi D. R., Cohen P. (1998). Mechanism of activation and function of protein kinase B. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 55–62 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80062-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M. (2011). A role for Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3 as integrators of dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission in mental health. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 36, 110011 10.1503/jpn.110011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Caron M. G. (2008). Looking at lithium: molecular moods and complex behaviour. Mol. Interv. 8, 230–241 10.1124/mi.8.5.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Del'guidice T., Sotnikova T. D., Lemasson M., Gainetdinov R. R. (2011). Beyond cAMP: the Regulation of Akt and GSK3 by dopamine receptors. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4:38 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R. (2011). The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 182–217 10.1124/pr.110.002642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2009). Akt/GSK3 signaling in the action of psychotropic drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49, 327–347 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Marion S., Rodriguiz R. M., Medvedev I. O., Sotnikova T. D., Ghisi V., Wetsel W. C., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2008). A beta-arrestin 2 signaling complex mediates lithium action on behavior. Cell 132, 125–136 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Marion S., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2005). An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Yao W. D., Kockeritz L., Woodgett J. R., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2004). Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5099–5104 10.1073/pnas.0307921101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J., Jerchow B. A., Wurtele M., Grimm J., Asbrand C., Wirtz R., Kuhl M., Wedlich D., Birchmeier W. (1998). Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with beta-catenin, APC, and GSK3beta. Science 280, 596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F., Serretti A., Colombo C., Lorenzi C., Tubazio V., Smeraldi E. (2004). A glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta promoter gene single nucleotide polymorphism is associated with age at onset and response to total sleep deprivation in bipolar depression. Neurosci. Lett. 368, 123–126 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Downes C. P., Hanley M. R. (1989). Neural and developmental actions of lithium: a unifying hypothesis. Cell 59, 411–419 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch N. J. (1974). Letter: lithium and magnesium-dependent enzymes. Lancet 2, 965–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C., Laje G., Olfson M., Marcus S. C., Pincus H. A. (2002). Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 1005–1010 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi G., Napolitano F., Ursini G., Taurisano P., Romano R., Caforio G., Fazio L., Gelao B., Di Giorgio A., Iacovelli L., Sinibaldi L., Popolizio T., Usiello A., Bertolino A. (2011). DRD2/AKT1 interaction on D2 c-AMP independent signaling, attentional processing, and response to olanzapine treatment in schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1158–1163 10.1073/pnas.1013535108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden C. L. (2000). Efficacy of lithium in mania and maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61 (Suppl 9), 35–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade J. F. (1949). Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med. J. Aust. 2, 349–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalecka-Franaszek E., Chuang D. M. (1999). Lithium activates the serine/threonine kinase Akt-1 and suppresses glutamate-induced inhibition of Akt-1 activity in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8745–8750 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb J. E., Bradshaw N. J., Soares D. C., Porteous D. J., Millar J. K. (2008). The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 36–64 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A., Pretty H., Hawton K., Geddes J. R. (2005). Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1805–1819 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P., Frame S. (2001). The renaissance of GSK3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 769–776 10.1038/35096075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J. N. (2008). Behavioral phenotyping strategies for mutant mice. Neuron 57, 809–818 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. (1995). Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378, 785–789 10.1038/378785a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryns K., Shamir A., Shapiro J., Daneels G., Goris I., Van Craenendonck H., Straetemans R., Belmaker R. H., Agam G., Moechars D., Steckler T. (2007). Lack of lithium-like behavioral and molecular effects in IMPA2 knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 881–891 10.1038/sj.npp.1301154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryns K., Shamir A., Van Acker N., Levi I., Daneels G., Goris I., Bouwknecht J. A., Andries L., Kass S., Agam G., Belmaker H., Bersudsky Y., Steckler T., Moechars D. (2008). IMPA1 is essential for embryonic development and lithium-like pilocarpine sensitivity. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 674–684 10.1038/sj.npp.1301431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Montigny C., Grunberg F., Mayer A., Deschenes J. P. (1981). Lithium induces rapid relief of depression in tricyclic antidepressant drug non-responders. Br. J. Psychiatry 138, 252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P., Li X., Jope R. S. (2002). Regulation of Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta phosphorylation by sodium valproate and lithium. Neuropharmacology 43, 1158–1164 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar-Finkelman H., Krebs E. G. (1997). Phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 by glycogen synthase kinase 3 impairs insulin action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9660–9664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian E. S., Hall D., Birnbaum M. J., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J. A. (2004). Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 36, 131–137 10.1038/ng1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embi N., Rylatt D. B., Cohen P. (1980). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 107, 519–527 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S. S., Downey W. E., 3rd, Colapietro A. M., Barak L. S., Menard L., Caron M. G. (1996). Role of beta-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science 271, 363–366 10.1126/science.271.5247.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould T. D., Chen G., Manji H. K. (2004). In vivo evidence in the brain for lithium inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 32–38 10.1038/sj.npp.1300283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould T. D., Manji H. K. (2002). Signaling networks in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K., Nikolakaki E., Plyte S. E., Totty N. F., Woodgett J. R. (1993). Modulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 family by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 12, 803–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro-Peled H., Hayashi-Takagi A., Seshadri S., Kamiya A., Brandon N. J., Sawa A. (2009). Neurodevelopmental mechanisms of schizophrenia: understanding disturbed postnatal brain maturation through neuregulin-1-ErbB4 and DISC1. Trends Neurosci. 32, 485–495 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E., Facchinetti V., Liu D., Soto N., Wei S., Jung S. Y., Huang Q., Qin J., Su B. (2006). SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell 127, 125–137 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope R. S. (2011). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the etiology and treatment of mood disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4:16 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidanovich-Beilin O., Milman A., Weizman A., Pick C. G., Eldar-Finkelman H. (2004). Rapid antidepressive-like activity of specific glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor and its effect on beta-catenin in mouse hippocampus. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 781–784 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidanovich-Beilin O., Woodgett J. R. (2011). GSK-3: functional Insights from Cell Biology and Animal Models. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4:40 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida S., Yamamoto H., Ikeda S., Kishida M., Sakamoto I., Koyama S., Kikuchi A. (1998). Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of beta-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10823–10826 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P. S., Melton D. A. (1996). A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8455–8459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer A., Louis J. V., Jaworski T., Van Leuven F. (2011). GSK3 and Alzheimer's disease: facts and fiction. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4:17 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvajo M., Mckellar H., Arguello P. A., Drew L. J., Moore H., Macdermott A. B., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J. A. (2008). A mutation in mouse Disc1 that models a schizophrenia risk allele leads to specific alterations in neuronal architecture and cognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7076–7081 10.1073/pnas.0802615105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law A. J., Kleinman J. E., Weinberger D. R., Weickert C. S. (2007). Disease-associated intronic variants in the ErbB4 gene are related to altered ErbB4 splice-variant expression in the brain in schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 129–141 10.1093/hmg/ddl449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A., Schlessinger J. (2010). Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117–1134 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Friedman A. B., Zhu W., Wang L., Boswell S., May R. S., Davis L. L., Jope R. S. (2007). Lithium regulates glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: implication in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 61, 216–222 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhu W., Roh M. S., Friedman A. B., Rosborough K., Jope R. S. (2004). In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3beta) by serotonergic activity in mouse brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1426–1431 10.1038/sj.npp.1300439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Hung M. C. (2010). Physiological regulation of Akt activity and stability. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2, 19–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman Z., Plotkin B., Tennenbaum T., Eldar-Finkelman H. (2008). Coordinated phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and protein kinase C beta II in the diabetic fat tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294, E1169–1177 10.1152/ajpendo.00050.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead P. A., Kinstrie R., Sibbet G., Rawjee T., Morrice N., Cleghon V. (2006). A chaperone-dependent GSK3beta transitional intermediate mediates activation-loop autophosphorylation. Mol. Cell 24, 627–633 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M. J., Benovic J. L., Codina J., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1990). Beta-arrestin: a protein that regulates beta-adrenergic receptor function. Science 248, 1547–1550 10.1126/science.2163110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell L. M., Ferguson S. S., Daaka Y., Miller W. E., Maudsley S., Della Rocca G. J., Lin F., Kawakatsu H., Owada K., Luttrell D. K., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1999). Beta-arrestin-dependent formation of beta2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science 283, 655–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell L. M., Gesty-Palmer D. (2010). Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 305–330 10.1124/pr.109.002436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Ge X., Frank C. L., Madison J. M., Koehler A. N., Doud M. K., Tassa C., Berry E. M., Soda T., Singh K. K., Biechele T., Petryshen T. L., Moon R. T., Haggarty S. J., Tsai L. H. (2009). Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell 136, 1017–1031 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri B., Salahpour A., Didriksen M., Ghisi V., Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2008). Antagonism of dopamine D2 receptor/beta-arrestin 2 interaction is a common property of clinically effective antipsychotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13656–13661 10.1073/pnas.0803522105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mines M. A., Yuskaitis C. J., King M. K., Beurel E., Jope R. S. (2010). GSK3 influences social preference and anxiety-related behaviors during social interaction in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome and autism. PLoS One 5, e9706 10.1371/journal.pone.0009706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Oerlinghausen B., Felber W., Berghofer A., Lauterbach E., Ahrens B. (2005). The impact of lithium long-term medication on suicidal behavior and mortality of bipolar patients. Arch. Suicide Res. 9, 307–319 10.1080/13811110590929550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves-Pereira M., Mundo E., Muglia P., King N., Macciardi F., Kennedy J. L. (2002). The brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene confers susceptibility to bipolar disorder: evidence from a family-based association study. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 651–655 10.1086/342288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien W. T., Harper A. D., Jove F., Woodgett J. R., Maretto S., Piccolo S., Klein P. S. (2004). Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta haploinsufficiency mimics the behavioral and molecular effects of lithium. J. Neurosci. 24, 6791–6798 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4753-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien W. T., Huang J., Buccafusca R., Garskof J., Valvezan A. J., Berry G. T., Klein P. S. (2011). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is essential for beta-arrestin-2 complex formation and lithium-sensitive behaviors in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3756–3762 10.1172/JCI45194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. Q., Lewis M. C., Ketterman J. K., Clore E. L., Riley M., Richards K. R., Berry-Scott E., Liu X., Wagner F. F., Holson E. B., Neve R. L., Biechele T. L., Moon R. T., Scolnick E. M., Petryshen T. L., Haggarty S. J. (2011). AKT kinase activity is required for lithium to modulate mood-related behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 1397–1411 10.1038/npp.2011.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker P. J., Caudwell F. B., Cohen P. (1983). Glycogen synthase from rabbit skeletal muscle; effect of insulin on the state of phosphorylation of the seven phosphoserine residues in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 130, 227–234 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiel C. J., Klein P. S. (2001). Molecular targets of lithium action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41, 789–813 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport S. I., Bosetti F. (2002). Do lithium and anticonvulsants target the brain arachidonic acid cascade in bipolar disorder? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 592–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth B. L., Sheffler D. J., Kroeze W. K. (2004). Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 353–359 10.1038/nrd1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryves W. J., Harwood A. J. (2001). Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280, 720–725 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid M. P., Woodgett J. R. (2001). PKB/AKT: functional insights from genetic models. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 760–768 10.1038/35096067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H. D., Duman R. S. (2010). Peripheral BDNF produces antidepressant-like effects in cellular and behavioral models. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 2378–2391 10.1038/npp.2010.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou M., Juel-Nielsen N., Stromgren E., Voldby H. (1954). The treatment of manic psychoses by the administration of lithium salts. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 17, 250–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serretti A., Benedetti F., Mandelli L., Calati R., Caneva B., Lorenzi C., Fontana V., Colombo C., Smeraldi E. (2008). Association between GSK-3beta -50T/C polymorphism and personality and psychotic symptoms in mood disorders. Psychiatry Res. 158, 132–140 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaldubina A., Johanson R. A., O'Brien W. T., Buccafusca R., Agam G., Belmaker R. H., Klein P. S., Bersudsky Y., Berry G. T. (2006). SMIT1 haploinsufficiency causes brain inositol deficiency without affecting lithium-sensitive behavior. Mol. Genet. Metab. 88, 384–388 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder S. H. (1976). The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: focus on the dopamine receptor. Am. J. Psychiatry 133, 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelberg B. D., Dela Cruz J., Law T. H., York J. D. (2005). Alteration of lithium pharmacology through manipulation of phosphoadenosine phosphate metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5400–5405 10.1074/jbc.M407890200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V., Ruel L., Woodgett J. R. (1996). Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr. Biol. 6, 1664–1668 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)70790-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V., Woodgett J. R. (1994). Mitogen inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta in intact cells via serine 9 phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 303(Pt 3), 701–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C., Cohen P. (1994). The alpha-isoform of glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle is inactivated by p70 S6 kinase or MAP kinase-activated protein kinase-1 in vitro. FEBS Lett. 338, 37–42 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80112-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C., Leighton I. A., Cohen P. (1993). Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. Biochem. J. 296(Pt 1), 15–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift J. L., Godin A. G., Dore K., Freland L., Bouchard N., Nimmo C., Sergeev M., De Koninck Y., Wiseman P. W., Beaulieu J. M. (2011). Quantification of receptor tyrosine kinase transactivation through direct dimerization and surface density measurements in single cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7016–7021 10.1073/pnas.1018280108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo L., Baldessarini R. J. (2009). Long-term lithium treatment in the prevention of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 18, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein M., Mccarthy J. F., Austin K. L., Greden J. F., Young E. A., Blow F. C. (2006). What happened to lithium? Antidepressant augmentation in clinical settings. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 1219–1225 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waraich R. S., Weigert C., Kalbacher H., Hennige A. M., Lutz S. Z., Haring H. U., Schleicher E. D., Voelter W., Lehmann R. (2008). Phosphorylation of Ser357 of rat insulin receptor substrate-1 mediates adverse effects of protein kinase C-delta on insulin action in skeletal muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11226–11233 10.1074/jbc.M708588200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. S., Cheng L., Mudge A. W., Harwood A. J. (2002). A common mechanism of action for three mood-stabilizing drugs. Nature 417, 292–295 10.1038/417292a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. S. B., Harwood A. J. (2005). “3Li lithium metallotherapeutics,” in Metallotherapeutic Drugs and Metal-Based Diagnostic Agents: The Use of Metals in Medicine, eds Gielen M., Tiekink E. R. T. (Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wieley & Sons Ltd; ), 1–18 [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett J. R. (1990). Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/factor A. EMBO J. 9, 2431–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett J. R. (2001). Judging a protein by more than its name: GSK-3. Sci. STKE 2001, RE12 10.1126/stke.2001.100.re12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Phiel C. J., Spece L., Gurvich N., Klein P. S. (2003). Inhibitory phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in response to lithium. Evidence for autoregulation of GSK-3. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33067–33077 10.1074/jbc.M212635200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]