Abstract

Despite the role of aerobic glycolysis in cancer, recent studies highlight the importance of the mitochondria and biosynthetic pathways as well. PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) is a key transcriptional regulator of several metabolic pathways including oxidative metabolism and lipogenesis. Initial studies suggested that PGC1α expression is reduced in tumors compared to adjacent normal tissue. Paradoxically, other studies show that PGC1α is associated with cancer cell proliferation. Therefore the role of PGC1α in cancer and especially carcinogenesis is unclear. Using Pgc1α-/- and Pgc1α+/+ mice we show that loss of PGC1α protects mice from azoxymethane induced colon carcinogenesis. Similarly, diethylnitrosamine induced liver carcinogenesis is reduced in Pgc1α-/- mice compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice. Xenograft studies using gain and loss of PGC1α expression demonstrated that PGC1α also promotes tumor growth. Interestingly, while PGC1α induced oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle gene expression, we also observed an increase in the expression of two genes required for de novo fatty acid synthesis, ACC and FASN. In addition, SLC25A1 and ACLY, which are required for the conversion of glucose in to acetyl CoA for fatty acid synthesis, were also increased by PGC1α, thus linking the oxidative and lipogenic functions of PGC1α. Indeed, using 13C stable isotope tracer analysis we show that PGC1α increased de novo lipogenesis. Importantly, inhibition of fatty acid synthesis blunted these progrowth effects of PGC1α. In conclusion, these studies show for the first time that loss of PGC1α protects against carcinogenesis and that PGC1α coordinately regulates mitochondrial and fatty acid metabolism to promote tumor growth.

Keywords: Cancer metabolism, Warburg Effect, oxidative metabolism, lipogenesis, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Pioneering work by Otto Warburg described the ability of tumor cells to use glycolysis to generate ATP and lactic acid, even in the presence of oxygen, i.e., aerobic glycolysis, or as it is commonly called, the Warburg Effect (1). However, increased glucose utilization cannot be explained solely by increased ATP production as initially proposed by Warburg. Besides the generation of ATP, there are a number of other benefits of increased glucose metabolism. Glucose serves as a precursor for biosynthesis of molecules involved in generating biomass such as nucleic acids and lipids. Indeed, increased nucleic acid and lipid synthesis play an important role in many cancers (2-4). Therefore, the ability of cancer cells to coordinate glucose metabolism is a crucial aspect of the metabolic phenotype. This has prompted interest into understanding and targeting key molecules regulating glucose metabolism.

PPARγ Co-activator 1α (PGC1α) is a major regulator of several key metabolic pathways. PGC1α was initially identified as the key factor driving thermogenesis in brown fat (5). Numerous studies have since demonstrated a key role for PGC1α in inducing the expression of genes of oxidative phosphorylation and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in various tissues (6-8). PGC1α also plays an important role in regulating other metabolic pathways. Recent studies show that PGC1 also promote anabolic pathways such as de novo lipogenesis (9, 10). This is accompanied by an increase in the pentose phosphate pathway in order to generate NADPH for fatty acid synthesis (9). This highlights the important role that PGC1α plays in regulating multiple aspects of metabolism in addition to its ability to promote oxidative metabolism.

Initial studies on the role of PGC1α in cancer showed an association between reduced expression of PGC1α compared to normal adjacent tissue (11). The ability of PGC1 to drive mitochondrial function led to speculation that reduced PGC1α in tumors may be responsible for the Warburg effect. Indeed, several studies showed decreased PGC1α expression was associated with reduction in mitochondrial function and increased growth (12, 13). Although the Warburg effect is a well-described phenomenon, more recent studies demonstrate that mitochondrial function is required for transformation and tumor growth (14-16). This supports several studies suggesting a potential procancer role for PGC1α (17-19). These studies highlight the conflicting data regarding the role of PGC1α in maintaining tumor growth. Regardless of the associations between PGC1 expression and established tumors or cell lines, whether or not PGC1α is involved in tumorigenesis is not known. Therefore, we have taken an approach employing gain and loss of PGC1α expression to determine the role of PGC1α on tumorigenesis and tumor growth.

Materials and methods

Animal Studies

Protocols were approved by the UMB Animal Care and Use Committee and performed under veterinary supervision. PGC1α knockout (Pgc1α-/-) mice were obtained from Dr. Bruce Spiegelman (Dana-Farber Cancer Instutite/Harvard Medical School) (20). These mice have been observed for over two years and did not appear to be any colon or tumor development (data not shown and personal communication, Dr. Bruce Spiegelman and Jiandie Lin). Colons and livers were removed from mice and RNA isolated using Trizol as previously described (21, 22). Colon carcinogenesis was induced by injecting mice once per week with 10mg/kg AOM for 8 weeks as previously described (23). Mice were monitored for 25 weeks and then euthanized. Colons were removed and fixed for tumor analysis. For liver carcinogenesis, mice were injected at 14 days of age with 25 mg/kg diethylnitrosamine (DEN). Mice were followed out to 24 weeks or 40 weeks and then euthanized. Livers were removed for tumor anlaysis. Formalin fixed liver tissue was paraffin embedded and 5μM sections cut by the University of Maryland Greenebaum Center Pathology Core. Liver sections from mice euthanized at 24 weeks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and pathological analysis and tumor number determined blindly by a board certified pathologist (Dr. Twaddel). For liver sections from mice euthanized at 40 weeks, due to greater tumor formation in the Pgc1α+/+ mice it was not possible to count individual tumors since tumors grew into each other. Therefore tumor burden was determined by measuring tumor area. Colons were examined blinded under a dissecting scope and gross tumor number determined. For xenograft studies, 1×106 cells were injected s.c. into the flank of SCID mice mice (Taconic) in 100 μL of media. Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days using a digital caliper and volume calculated as previously described (22). At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized, tumors harvested and processed for RNA, protein and histopathology. Data were obtained from 8-12 mice per experimental group and experiments repeated at least two times. For studies inhibiting fatty acid synthesis, HT29 pcDNA control and pcDNA PGC1α expressing cells were inoculated into the flank of SCID mice. As soon as tumors were palpable, mice were administered 10 mg/kg C75 (Toronto Chemical Company) twice a week. And tumor growth monitored. 5 mice per group were used for these experiments. For XCT790 inverse ERRα agonist experiments, wildtype mice were treated with 25 mg/kg for three days by IP injection. Livers were removed, RNA extracted and real time PCR performed as described below.

Cell culture and cell line generation

HT29 and Colo205 cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in DMEM (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% FBS and pen/strep. ATCC characterizes cell lines by short tandem repeat profiling. Experiments were performed with cells at less than 25 passages after receipt. Lentiviral expression shRNA against PGC1α was obtained from Sigma. Lentivirus particles expressing shRNA against PGC1 were produced according to manufactures directions in 293T cells. Virus was transduced into Colo205 cells along with 8μg/mL polybrene and cells selected with puromycin. PGC1α knockdown was confirmed by RT-PCR and western blotting for PGC1α (Calbiochem). For PGC1α gain of function studies, control pcDNA and pcDNA expressing PGC1α were transfected into HT29 cells and cells selected in G418 to obtain PGC1α expressing stable cells. PGC1α over expression was confirmed by RT-PCR and western blotting for PGC1α (Calbiochem).

Western blotting

Tissues and cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and proteins harvested. 100 μg of protein was separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were incubated with PGC1α (Calbiochem), SREBP1c (BD Bioscience) and actin (Sigma) antibodies and secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research). Proteins were visualized using ECL.

Cell growth studies

Cells were plated at 10,000 cells/well in a 6 well plate and cells counted every two days using a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion as previously described (22).

Real time PCR

RNA was extracted from cells and tissues using Trizol as previously described (21, 22). cDNA was synthesized and quantitative RT PCR performed using SYBR Green as previously described using gene specific primers (Supplemental table I) and normalized to actin as a control (21, 22).

Analysis of lipid metabolism

For total TAG determination and TAG synthesis, the lipids were extracted by the Folch method from individual liver and tumor tissues. Total upper phase was dried down, resuspended in isopropanol and assayed with triglyceride kit (Sigma) by the University of Maryland Nutrition and Obesity Research Core. Equivalent of 5 mg for liver tissue and 1 mg for tumor tissue were analyzed with thin layer chromatography extractions. Tissue lipids were separated with chloroform/acetone/acetic acid (96:4:1) as solvent. The lipids were visualized with phosphomolybdenum vapor.

For metabolic flux analysis we used stable isotope based tracer analysis. [U6-13C6]-glucose (>99% purity and 99% isotope enrichment for each carbon position; Cambridge Isotope Labs) was used as a tracer. Mice with HT29 pmscv and HT29 PGC1α expressing xenografts were administered 13C glucose and tumors and plasma collected 3 hours later. Specific extractions and analysis were performed as previously described and below (10, 24, 25). Fatty acids were extracted by saponification of Trizol cell extracts after removal of the RNA containing supernatant with 30% KOH and 100% ethanol using petroleum ether. Fatty acids were then converted to their methylated derivatives using 0.5 N methanolic-HCl. Palmitate was monitored at m/z 270. The enrichment of acetyl units and the synthesis of new lipid fraction were determined using the mass isotopomers of palmitate with the enrichment of 13C-labeled acetyl units used to reflect synthesis of the new lipid fraction as determined by mass isotopomer distribution analysis (MIDA). Media C13/C12 ratios in released CO2 and used as the direct measure of glucose oxidation.

Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

Mass spectral data were obtained on the HP5973 mass selective detector connected to an HP6890 gas chromatograph. The settings are as follows: GC inlet 230 °C, transfer line 280 °C, MS source 230 °C MS Quad 150 °C. An HP-5 capillary column (30m length, 250μm diameter, 0.25μm film thickness) was used for glucose, ribose, and lactate analysis. A Bpx70 column (25m length, 220μm diameter, 0.25μm film thickness, SGE Incorporated, Austin, TX) was used for fatty acid analysis with specific temperature programming for each compound studied as previously described.

Statistical analysis

For growth and gene expression analysis, Students T test was used to determine statistical significance. Fishers Exact test was applied to colon cancer incidence with significance defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Loss of PGC1 protects against tumorigenesis

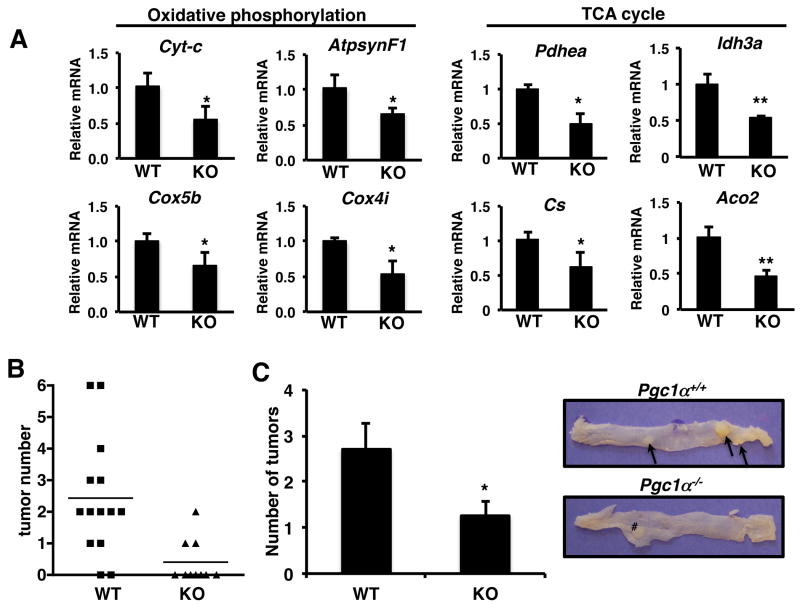

One of the first studies to show an association between PGC1α and cancer demonstrated that PGC1α levels are reduced in colon derived tumor tissue compared to normal adjacent tissue (11). PGC1α is abundantly expressed throughout the small intestine and colon and in the stem cell crypt compartment and at the top of intestinal crypts (26). Therefore initially we examined the role of PGC1α in colon tumorigenesis. Mitochondrial gene targets of PGC-1α involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation were down regulated from the colons of PGC1α-/- mice compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice (Figure 1A). We also examined whether there was a compensatory increase in PGC1β to due to loss of PGC1α but found a decrease in expression (Supplemental Figure 1A). We then induced tumorigenesis using a colon specific carcinogen, azoxymethane (AOM). AOM induced tumors originate from epithelial cells lining the colon and grows as polyps or adenomas which similar to colon carcinoma in humans. Mice were examined for colorectal tumors 25 weeks following the last AOM injection. Despite the reduction in oxidative phosphorylation gene expression in the Pgc1α-/- mice, there was a significant reduction in tumor incidence in the of Pgc1α-/- mice. 87% of Pgc1α+/+ mice had colonic polyps whereas less than 30% of the Pgc1α-/- mice had polyps (Figure 1B, p < 0.01). In addition, in mice with tumors, loss of PGC1α reduced tumor multiplicity more than 50% (figure 1C). Therefore, despite studies showing reduced PGC1α expression in colon-derived tumors compared to normal tissue, loss of PGC1α protects against colon tumorigenesis.

Figure 1.

Loss of PGC1α protects against colon carcinogenesis. A) Colons from PGC1α-/- mice have reduced oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle gene expression. RNA was isolated from the colons of mice, cDNA synthesized and RTPCR performed for the indicated genes. Actin was used as a control. N=4-6 ± S.E. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. B) Loss of PGC1α significantly reduces the number of mice with colon tumors. p < 0.01, Fishers exact test. 87% of Pgc1α+/+ (13/15) and 30% of Pgc1α-/- (3/10) had colon tumors. Colon carcinogenesis was induced in Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- mice and tumor number measured as described in materials and methods. C) Loss of Pgc1α reduces tumor multiplicity. Right panel, representative colon from Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- mice following AOM treatment. Arrows indicate tumors. # indicates mesenteric lymph node. N=12 Pgc1α+/+ and 3 Pgc1α-/- mice since only mice with tumors are included. *p < 0.05.

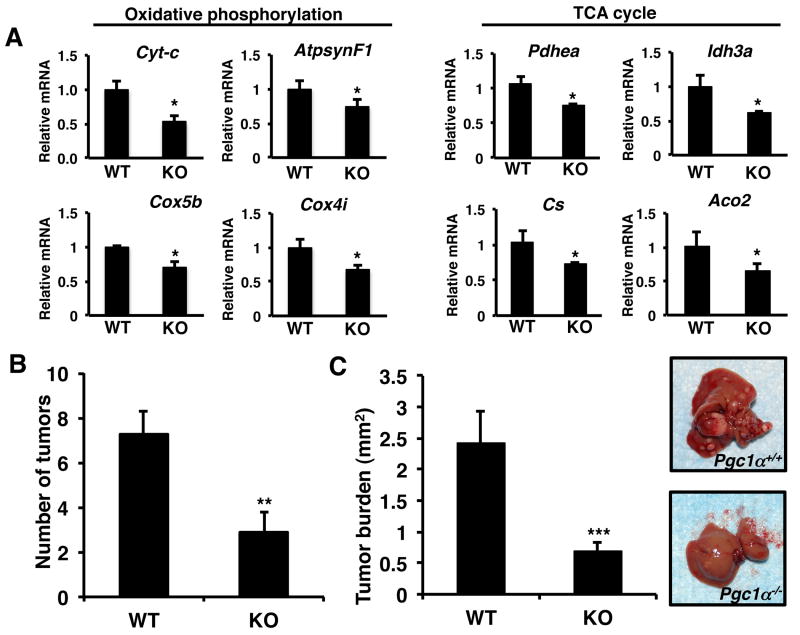

Next we wanted to determine whether the ability of PGC1α to promote tumorigenesis was specific for the colon. PGC1α plays a key role in regulating glucose homeostasis in the liver and represents one of the most well studied sites of action of PGC1α (7). Initially we examined the livers of Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- mice for the expression of PGC1α targets. Similar to previous studies loss of PGC1α was associated with a reduction in the expression of oxidative phosphorylation and tricarboxylic acid cycle genes (Figure 2A) (8). We also observed a decrease in PGC1β, however it was not statistically significant (Supplemental Figure 1B). Next we examined the role of Pgc1α on liver tumorigenesis using Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- mice. Liver carcinogenesis was induced in fourteen-day-old mice using the liver specific carcinogen, DEN. DEN is a DNA alkylating agent that induces pericentral foci and small dysplastic hepatocytes leading to multifocal HCC displaying characteristic similar to that observed in human HCC. After 24 weeks, the number of liver tumors in Pgc1α-/- mice was reduced ∼ 60% compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice (Figure 2B). After 40 weeks following DEN treatment we were not able to distinguish individual tumors in Pgc1α+/+ mice. Therefore we examined mice for tumor burden. We observed a significant decrease in tumor burden in the livers of Pgc1α-/- mice compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice 40 weeks following DEN treatment (Figure 2C and right panel). These data demonstrate that despite the reduction in oxidative phosphorylation and tricarboxylic acid cycle gene expression in Pgc1α knockout mice, loss of PGC1α protects against carcinogenesis.

Figure 2.

Loss of PGC1α protects against liver carcinogenesis. A) Livers from Pgc1α-/- mice have reduced oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle gene expression. RNA was isolated from the livers of mice, cDNA synthesized and RTPCR performed for the indicated genes. Actin was used as a control. N=4-6 ± S.E. * p < 0.05. B) Loss of Pgc1α-/- reduces DEN induced tumor number at 24 weeks. C) Reduced tumor burden in Pgc1α+/+ mice after 40 weeks. Right panel – representative liver from Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- mice, 40 weeks after DEN treatment. Liver carcinogenesis was induced in 14 day old mice using DEN and mice examined at 24 weeks and 40 weeks for tumor development. N=8-12 ± S.E., **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.0005.

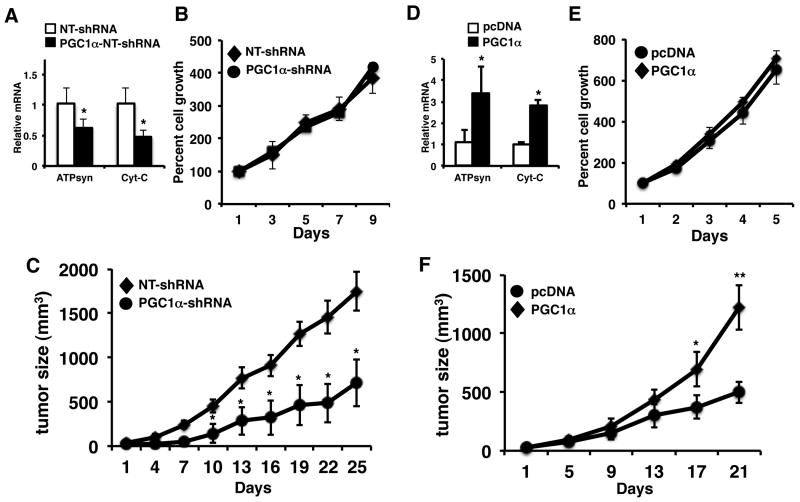

PGC1α promotes tumor growth in vivo

Pgc1α whole body knockout mice exhibit multiple metabolic abnormalities (20). In addition, given the ability of PGC1α to control the expression of metabolic genes, it may be altering the metabolism of the carcinogens used. Therefore we wanted to determine the effect of PGC1α in a more defined setting. We reduced the expression of PGC1α in the Colo205 human colorectal cancer cell line using a lentiviral-based shRNA against PGC1α (Supplemental Figure 1C). Knockdown of PGC1α led to a reduction in oxidative phosphorylation and PGC1β gene expression (Figure 3A, Supplemental Figure 1D). Interestingly, despite the decrease in mitochondrial gene expression, we did not observe a difference in cell proliferation in vitro (Figure 3B). Since PGC1α plays a major role in nutrient sensing and homeostasis, we examined the effect of loss of PGC1α on tumor growth in vivo. We inoculated Colo205 cells expressing NT shRNA or PGC1α-shRNA into the flank of SCID mice and measured tumor xenograft growth. Growth of PGC1α-shRNA expressing cells was reduced almost 60% compared to control NT-shRNA expressing cells (Figure 3C). Next we wanted to determine if PGC1 could promote tumor growth by overexpressing PGC1α in the HT29 colon cancer cell line (which expresses little PGC1α) (Supplemental Figure 1E). Ectopic expression of PGC1α increased the expression of genes driving oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, we observe that PGC1α promotes the expression of PGC1β (Supplemental Figure 1F). Similar to the knockdown data, altering PGC1α expression did not appear to alter cell proliferation in vitro (Figure 3E). We then examined the effect of PGC1α expression on tumor growth in vivo. Control and Pgc1α expressing HT29 cells were inoculated into the flank of SCID mice and tumor growth measured. As shown in Figure 3F, PGC1α overexpressing tumors grew almost 3× as large as control tumors. Although PGC1α did alter cell growth in vitro, these studies demonstrate a direct role for PGC1α in promoting tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 3.

PGC1α promotes tumor growth in vivo. A) Knockdown of PGC1α in Colo205 cells causes a decrease in mitochondrial gene expression (left panel). RNA was isolated from non-target control and PGC1α-shRNA Colo205 cells. RTPCR was performed for the ATPsynβ1 and Cyt-C and values normalized to actin. N=3 ± SD, *p < 0.05. PGC1α knockdown does not alter cell growth in vitro. NT-shRNA and PGC1α-shRNA cells were plated and counted every two days as described in materials and methods. N=3 ± SD. B) Knockdown of PGC1α reduces growth of Colo205 tumors compared to control NT-shRNA Colo205 tumors. Cells were inoculated into the flank of mice and tumor growth measured. N=8-10 ± SD, *p < 0.05. D) Overexpression of PGC1α in HT29 cells increases mitochondrial gene expression (left panel). RNA was isolated from pcDNA control and PGC1α overexpressing HT29 cells. RTPCR was performed for the ATPsynβ1 and Cyt-C and values normalized to actin. N=3 ± SD, *p < 0.05. E) Ectopic expression of PGC1α does not alter cell growth in vitro. Control and PGC1α expressing cells were plated and counted every two days as described in materials and methods. N=3 ± SD. F) Ectopic expression of PGC1α increases the growth of HT29 tumors compared to control pCDNA HT29 tumors. Cells were inoculated into the flank of mice and tumor growth measured. N=8-12 ± SE. * p <0.05, ** p < 0.005.

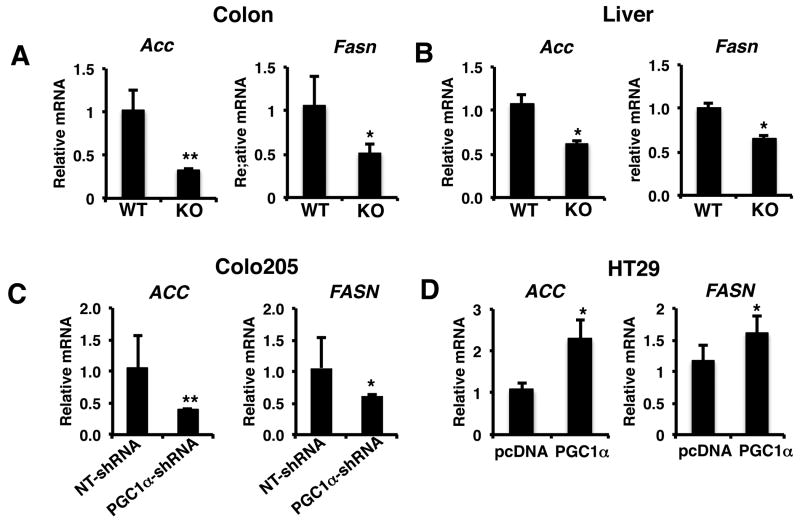

PGC1α promotes the expression of genes driving de novo fatty acid synthesis

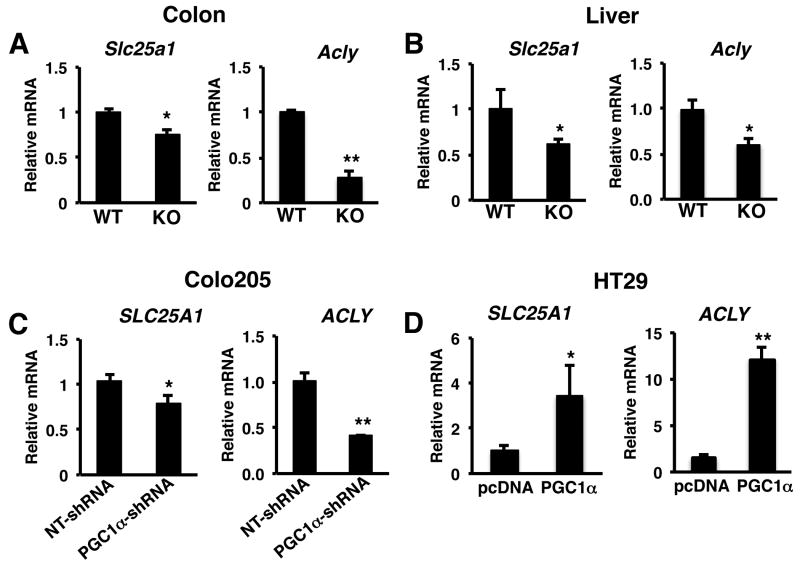

Recent studies have demonstrated that despite the well-known role of Pgc1α in driving oxidative metabolism, it can also promote de novo fatty acid synthesis (9, 10). Lipogenesis has become recognized as playing an important role in tumorigenesis and cancer cell growth (2). Indeed, the key proteins controlling fatty acid synthesis from acetyl coA, acetyl Co carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FASN) play an important role in promoting cancer growth (27, 28). As shown in figure 4A the gene expression of Acc and Fasn were reduced in the colons of Pgc1α-/- mice compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice. Similarly, the expression of Acc and Fasn were also reduced in the livers of Pgc1α-/- mice compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice (Figure 4B). We then examined lipogenic gene expression from the tumor xenografts with loss and gain of PGC1α expression. Knockdown of PGC1α in colo205 tumors led to significant reduction in expression of both ACC and FASN (Figure 4C). Conversely, expression of PGC1α in HT29 tumors increased ACC and FASN expression (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

PGC1α regulates fatty acid synthesis gene expression. A) Colons and B) livers from Pgc1α-/- mice have reduced expression of ACC and FASN expression compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice. C) Knockdown of PGC1α reduces ACC and FASN expression in Colo205 tumors. D) Ectopic expression of PGC1α promotes ACC and FASN gene expression in HT29 tumors. RNA was isolated from tissue and RT-PCR performed for ACC and FASN as described in materials and methods. N=8-12 ± S.E. *p < 0.05, **p <0.01.

The induction of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation by PGC1 raises the question as to how these pathways are linked to fatty acid synthesis. Acetyl CoA is required for de novo fatty acid synthesis from glucose. However, acetyl CoA produced from glucose is generated in the mitochondria, whereas fatty acid synthesis occurs in the cytoplasm. In order to use acetyl CoA for fatty acid synthesis, it is converted to citrate in the TCA cycle and shuttled out of the mitochondria by the mitochondrial citrate transporter, solute carrier family 25,member 1 (SLC25A1). In the cytoplasm ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) converts the mitochondrial-produced citrate into oxaloacetate and acetyl CoA. Loss of PGC1α expression in PGC1α-/- mice or knockdown of PGC1 in colo205 cells led to a reduction in SLC25A1 and ACLY (Figure 5A-5C). In contrast, the expression of SLC25A1 and ACLY were increased in HT29 tumors overexpressing PGC1α (Figure 5D). Together, these data suggest that PGC1α coordinately regulates gene expression promoting metabolic pathways required for converting glucose into fatty acids.

Figure 5.

PGC1α links mitochondrial and lipogenic functions by inducing SLC25A1 and ACLY. E) PGC1α promotes the expression of ACLY. A) Colons and B) livers from Pgc1α-/- mice have reduced expression of Slc25a1 and Acly compared to Pgc1α+/+ mice. C) Knockdown of PGC1α reduces SLC25A1 and ACLY expression in Colo205 tumors. D) Ectopic expression of PGC1α promotes SLC25A1 and ACLY gene expression in HT29 tumors. RNA was isolated from tissue and RT-PCR performed for SLC25A1 and ACLY as described in materials and methods. N=8-12 ± S.E. *p < 0.05, **p <0.01.

SREBP1 is one of the most well studied transcription factors driving the lipogenic gene expression program in the liver (29). A number of studies demonstrate that SREBP1c and it ability to promote lipogenesis play a role in increased tumor development and growth (30). SREPB1c exists as a precursor in the cytoplasm and is activated by cleavage and subsequent nuclear localization of the mature form (2, 29). This prompted us to examine the livers and colons of wildtype and knockout mice for the expression of mature SREPB1c. Loss of PGC1α did not alter the expression of cleaved SREBP1c in the liver and colons from mice (Supplemental figure 2A and 2B). In addition, we did not detect SREBP1c protein expression in HT29 and Colo205 xenografts (data not shown). This further suggests that PGC1α does not mediate its effects by regulating mature SREBP1c expression.

PGC1α directs programs of gene expression by interacting with transcription factors. One of the most well characterized transcription factors mediating the effects of PGC1α on energy metabolism is ERRα (31, 32). Interestingly, ERRα has also been shown to promote tumor growth and is associated with reduced survival in several cancers (33-37). We examined the effect of ERRα inhibition in the liver of wildtype C57Bl/6J using an ERRα inverse agonist, XCT790. Inhibition of ERRα decreased the expression of cytochrome C expression, a typical target of PGC1α and ERRα (Supplemental figure 2A). However we did not observe a difference in SLC25A1, ACLY, ACC and FASN gene expression following treatment with the ERRα antagonist (Supplemental figure 2B-E). While ERRα may be responsible for the effects of PGC1α on gene expression driving cellular bioenergetics, the data suggests that ERRα is not responsible for the effects of PGC1α on lipogenic gene expression.

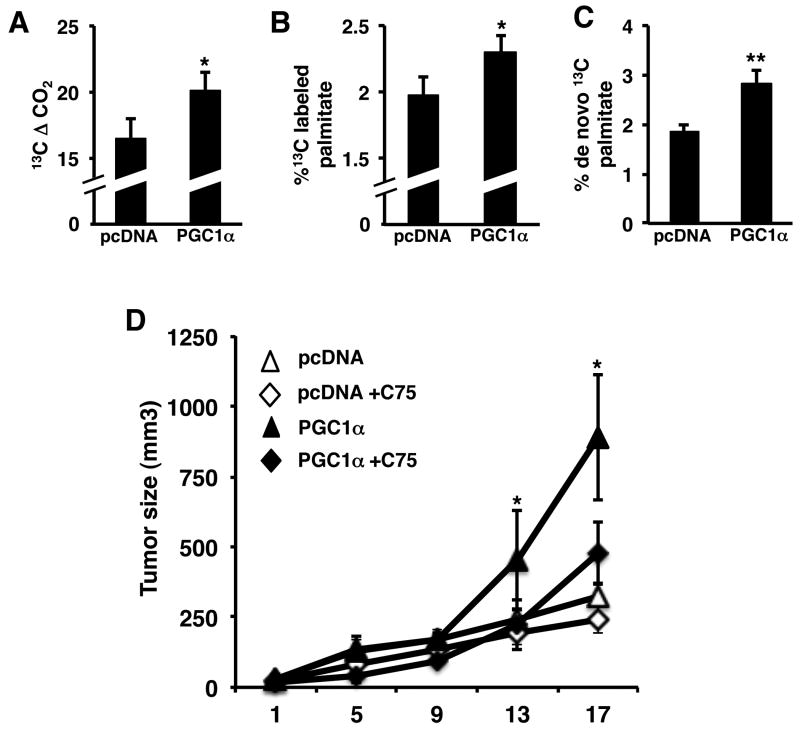

PGC1α promotes lipogenesis

Given the ability of PGC1α to promote lipogenic gene expression, we next examined whether PGC1 promoted lipid accumulation. Initially we examined triacylglycerol (TAG) levels in Pgc1α+/+ and Pgc1α-/- liver and HT29 xenograft tumor tissue. TAG content was significantly reduced in the livers of Pgc1α-/- mice (Supplemental figure 4A). In HT29 tumors expressing Pgc1α, TAG levels were significantly increased (Supplemental figure 4B). Measuring TAG levels shows mainly the steady state accumulation of lipids, and is not a direct measure of synthesis. Therefore we used stable 13C isotope tracer studies to determine the effect of PGC1α on de novo fatty acid synthesis. Mice with control or PGC1α expressing xenografts were established and administered 13C glucose and plasma and tumors harvested 3 hours later. Plasma from mice bearing PGC1 expressing tumors showed increased 13CO2 concentration (Figure 6A). This demonstrates the increased glucose utilization in mice with PGC1α expressing tumors even over the course of a short incubation time (3 hr). We then directly examined fatty acid synthesis in tumors by measuring the incorporation of 13C from glucose into palmitate, the product of FASN. Despite the short incubation, ∼2% of the palmitate derived from tumors was 13C labeled. This increased more than 15% increase in the Pgc1α expressing tumors (Figure 6B). We also examined plasma 13C labeled palmitate to determine if the labeled palmitate was derived from non-tumor tissue and subsequently taken up by tumors. The percent of 13C labeled palmitate in plasma was much less than 1% of the total palmitate and did not change in plasma from mice bearing PGC1α expressing tumors, confirming that palmitate was being produced by tumor (Supplemental figure 4C). Subsequent positional mass isotope analysis showed that the increase in labeled palmitate was due to increased de novo synthesis, which was increased over 50% compared to control tumors (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

PGC1α promotes tumor growth by increasing de novo fatty acid synthesis. A) PGC1α increases 13CO2 production from glucose. B) PGC1 increases incorporation of glucose into palmitate. C) PGC1α promotes de novo palmitate synthesis. Mice with vector control or PGC1 expressing tumor xenografts were administered [U6]-13C glucose for 3 hr, plasma and tumor tissue harvested and stable isotope analysis performed as described in materials and methods. D) Inhibiting fatty acid synthesis blocks the effect of PGC1 on tumor growth. HT9 control and PGC1α expressing xenografts were established in SCID mice. Once tumor formation was detected mice were treated with 10 mg/kg C75 and tumors measured for the indicated time. N=5 ± S.D., p < 0.05.

PGC1α mediated induction of fatty acid synthesis promotes tumor growth

These studies demonstrate that Pgc1α expression is associated with induction of a program of lipogenic gene expression and de novo lipogenesis. However, it does not demonstrate that increased fatty acid synthesis per se is mediating the effects of Pgc1α on tumor growth. To test this we established pcDNA control and PGC1α expressing xenografts in mice and inhibited fatty acid synthesis with the FASN inhibitor C75 once tumors had formed (38). We used a lower dose of C75 than previous studies given the ability of C75 to inhibit tumor growth. Similar to the studies above, Pgc1α expressing tumors grew about 3 times as large as control tumors (Figure 6D). C75 reduced the growth of the control tumors a about 20%, although it was not statistically significant. In contrast C75 treatment of mice with tumors expressing PGC1α significantly reduced the growth of tumors ∼ 50%. This demonstrates that the tumor growth promoted by PGC1 is mediated in part via induction of fatty acid synthesis.

Discussion

Altered cancer metabolism has become recognized as a hallmark of cancer. While the Warburg effect and glycolysis are recognized as key aspects of tumor metabolism, tumors cells need to be able to coordinate energy generating and biosynthetic pathways in order to effectively promote cell proliferation (2-4). PGC1α is a key metabolic regulator that controls multiple aspects of glucose metabolism. Our studies demonstrate a novel role for PGC1α in promoting carcinogenesis and tumor growth. This effect appears to be mediated via coordinating the induction of a gene expression program that facilitates the conversion of glucose to fatty acids.

Elevated fatty acid synthesis has become recognized as an important pathway in cancer (2). In addition to generating membranes for biomass, lipids are used for signaling pathways that are often elevated in many cancers. Lipids play an important role in transmitting signals from the plasma membrane via lipid second messengers and eicosanoids. In addition, lipid modification of a number of oncogenes including RAS and AKT is required for full oncogenic activation(39, 40). Therefore the ability of PGC1α to modulate fatty acid synthesis would also provide cancer cells with precursors for signal transduction pathways regulating cell growth.

Although increased mitochondrial function in terms of the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation are typically associated with reduced growth, recent studies highlight the need for oxidative phosphorylation and the TCA cycle in promoting tumor growth (14-16). Indeed, several studies demonstrate a potential role for PGC1α in this process. Ectopic expression of KRAS in NIH3T3 fibroblasts leads to increased proliferation, which is associated with increased PGC1α and it's down stream targets genes (17). The ability of breast cancer cells to metastasize to the brains of mice was also associated with increased PGC1α expression and its target genes (18). Another study showed that activation of PPARδ induced cell proliferation, which was associated with increased PGC1α expression (41). Despite the association between PGC1α and cell growth, a direct role for PGC1α was not shown. A more recent report showed that knockdown of PGC1α in prostate cancer cells reduced growth in vitro (42). However, the prostate cell lines used have very little PGC1α raising questions regarding PGC1α knockdown.

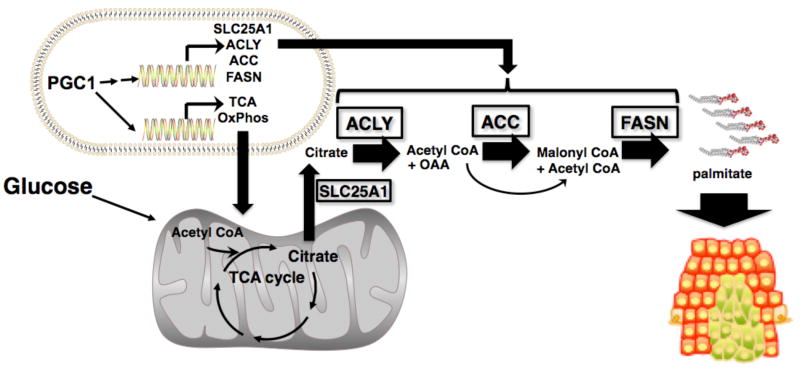

These studies highlight the observation that multiple metabolic pathways regulate tumor cell growth and that increased mitochondrial function per se does not necessarily inhibit growth. The coordinated induction of TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation by PGC1α would provide cells with a strong metabolic advantage. Making a daughter cell is a bioenergetically costly endeavor whereby glucose is used for both energy and biosynthetic precursors. Induction of oxidative phosphorylation and the TCA cycle by PGC1α would enable cells to make more glucose available for biomass generation since oxidative phosphorylation and the TCA cycle are more efficient at generating energy. The importance of lipogenesis in tumor metabolism highlights another need for the induction of the TCA cycle by PGC1α. De novo fatty acid synthesis from glucose requires acetyl CoA. However, acetyl CoA is produced in the mitochondria, whereas fatty acid synthesis occurs in the cytosol. Therefore the TCA cycle is required for converting mitochondrial-generated acetyl CoA into citrate. Our studies show that PGC1α plays an additional role in this process by (directly or indirectly) inducing the expression of genes involved in these pathways and bridging the known mitochondrial and lipogenic functions of PGC1α. ACLY promotes the conversion of citrate back to OAA and acetyl CoA, providing substrates for fatty acid synthesis by ACC and FASN. Therefore our studies suggest that PGC1 is coordinating energy production and mitochondrial function with biosynthetic pathways to fuel cancer growth.

The ability of PGC1 to regulate energy metabolism occurs in part via coactivation of the transcription factor ERRα (31, 32). Recent studies highlight an important role for ERRα in promoting cancer growth in several different cancer types (35, 36, 43). It has also been reported that higher expression of ERRα is associated with a worse prognosis for several cancers (33, 34, 37). A stronger connection between ERRα and PGC1α was suggested in a recent study which showed that tumorigenesis of fibroblasts by KRAS is mediated in part by PGC1α and ERRα (44). However, using an inverse agonist of ERRα, we did not observe an alteration to lipogenic gene expression in livers of mice. Therefore, while PGC1α might regulate the expression of genes driving energy metabolism, it most likely regulates lipogenic gene expression independently of ERRα. In contrast to ERRα SREBP1c is a key transcription factor mediating the program of lipogenesis. We did not observe a difference in expression of mature SREBP1c in livers or colons of Pgc1α-/- mice. Further ruling out a role for SREBP1c was the lack of SREBP1c in the Colo205 and HT29 xenografts. However, the possibility exists that PGC1α may be interacting and coactivating SREBP1c to increase lipogenic gene expression without altering the expression of SREBP1c. Future studies will elucidate the mechanism(s) by which PGC1α promotes lipogenesis in cancer, and whether the ability of PGC1α to promote gene expression programs regulating energy metabolism and lipogenesis is the result of distinct or related transcriptional programs. In addition, it remains to be determined if the effect of PGC1α on SLC25A1 and ACLY expression is a direct transcriptional effect or if it is secondary to induction of fatty acid synthesis.

The gain and loss of PGC1α expression studies presented here help to resolve the conflicting data regarding the role of PGC1 in cancer. However, a recent study overexpressing PGC1α in a breast cancer derived xenograft model did not observe a difference in growth in control tumors versus tumors expressing PGC1α (45). Since we observed an effect of PGC1α on tumor growth using both gain and loss of PGC1α expression in colon cancer cell lines, tissue specific differences may explain the contradictory results. Indeed recent studies suggest that PGC1α displays tissue specific differences in function (46). Hence PGC1α may be a target in colorectal and liver cancer, but not breast cancer.

Despite alterations in oxidative metabolism gene expression in vitro, we primarily observed an effect of PGC1α on tumor growth in vivo. The difference between in vitro and in vivo effects may be explained by the important role that PGC1α plays in nutrient response and signaling. In cell culture most nutrients such glucose and oxygen are not limiting. However, in vivo, the tumor microenvironment is an area of intense metabolic stress where nutrients are more limiting and therefore PGC1α may play a more important role. Our in vitro data also disagrees with a study showing that knocking down PGC1α in prostate derived cancer cells reduces growth in vitro (42). In addition to questions regarding expression of PGC1α in prostate as mentioned above, since PGC1α is primarily a transcriptional coactivator these differences may be attributable to the presence of cofactors that are expressed in a tissue or cell type specific manner. A recent manuscript described an antigrowth role for PGC1α in the colon (26). It is unclear as to the reasons for the contradictory result. Our studies utilized stable lentiviral and retroviral based technologies, whereas the recent study used adenoviral PGC1α injections directly into tumors. In addition, D'Errico et al found that loss of PGC1 protects against tumor formation. Possible differences may be attributed the chemical and genetic models used and strain differences. In addition, a question that is raised in general with regard to the studies by D'Errico et al., is that they show PGC1 prevents tumorigenesis by promoting ROS. However, studies show that PGC1α protects against ROS generation and upregulates antioxidant defense (47, 48).

Previous studies show that PGC1α is reduced in tumors (12, 13, 18). Most of these studies primarily show an association between PGC1α expression and tumor growth, and did not directly determine the role of PGC1α on cell growth. Therefore, PGC1α may play a role during carcinogenesis and then its expression decreases as tumors develop. Indeed, our data suggests that PGC1α represents a potential therapeutic target for chemoprevention. Obesity and diabetes are independent risk factors for developing liver and colon cancer (49, 50). Importantly, a number of studies show that PGC1α expression is elevated in the livers of obese/diabetic mice and patients. We also observe an increase of PGC1α in the colons of obese mice with type II diabetes (data not shown). Obese and diabetic individuals can be readily identified and therefore suggests that in these identifiable at risk patients, targeting PGC1α may be a useful cancer prevention strategy. Additionally, although our data points toward PGC1α playing a role in the early stages of cancer, our data using established cancer cell lines suggest that the presence of PGC1α is sufficient to promote tumor growth. Therefore notwithstanding the reduced expression of PGC1 in established tumors, PGC1α may be a therapeutic target in tumors where it is present.

Most studies showing that metabolism is altered in cancer have been done in established cancers. Therefore the role of metabolism on carcinogenesis is less well defined. These studies provide support for metabolism and its regulation by PGC1α as an important component of tumorigenesis and tumor growth. Importantly, PGC1 appears to accomplish this via inducing the expression of a gene expression program that coordinates the conversion of glucose into fatty acids. In conclusion these studies suggest that reducing PGC1 expression/activity represents a potential therapeutic approach for targeting multiple aspects of altered cancer metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

PGC1α coordinates the regulation of genes promoting the conversion of glucose to fatty acids. PGC1 increases the flow of glucose into the mitochondria where it is converted to citrate by inducing oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle genes. PGC1α also increases the expression of ACLY, which promotes the conversion of citrate to OAA and acetyl CoA. The acetyl CoA then participates in fatty acid synthesis via the PGC1 mediated induction of ACC and FASN.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the University of Maryland School of Medicine Nutrition and Obesity Research Core for technical assistance. This work was supported by the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center CRF, Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (KG081400) and NIDDK (DK064685) to G.D.G.

References

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nature reviews. 2007;7:763–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 2005;1:361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess SC, Leone TC, Wende AR, Croce MA, Chen Z, Sherry AD, et al. Diminished hepatic gluconeogenesis via defects in tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19000–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Summermatter S, Baum O, Santos G, Hoppeler H, Handschin C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} coactivator 1{alpha} (PGC-1{alpha}) promotes skeletal muscle lipid refueling in vivo by activating de novo lipogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;285:32793–800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinoza DO, Boros LG, Crunkhorn S, Gami H, Patti ME. Dual modulation of both lipid oxidation and synthesis by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha and -1beta in cultured myotubes. Faseb J. 2010;24:1003–14. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-133728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feilchenfeldt J, Brundler MA, Soravia C, Totsch M, Meier CA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and associated transcription factors in colon cancer: reduced expression of PPARgamma-coactivator 1 (PGC-1) Cancer letters. 2004;203:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellance N, Benard G, Furt F, Begueret H, Smolkova K, Passerieux E, et al. Bioenergetics of lung tumors: alteration of mitochondrial biogenesis and respiratory capacity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2566–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shakya A, Cooksey R, Cox JE, Wang V, McClain DA, Tantin D. Oct1 loss of function induces a coordinate metabolic shift that opposes tumorigenicity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:320–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogal V, Richardson AD, Karmali PP, Scheffler IE, Smith JW, Ruoslahti E. Mitochondrial p32 protein is a critical regulator of tumor metabolism via maintenance of oxidative phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1303–18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01101-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funes JM, Quintero M, Henderson S, Martinez D, Qureshi U, Westwood C, et al. Transformation of human mesenchymal stem cells increases their dependency on oxidative phosphorylation for energy production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6223–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700690104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, Weinberg S, Joseph J, Lopez M, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8788–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanathan A, Wang C, Schreiber SL. Perturbational profiling of a cell-line model of tumorigenesis by using metabolic measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5992–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502267102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen EI, Hewel J, Krueger JS, Tiraby C, Weber MR, Kralli A, et al. Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1472–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cormio A, Guerra F, Cormio G, Pesce V, Fracasso F, Loizzi V, et al. The PGC-1alpha-dependent pathway of mitochondrial biogenesis is upregulated in type I endometrial cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin J, Wu PH, Tarr PT, Lindenberg KS, St-Pierre J, Zhang CY, et al. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell. 2004;119:121–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drori S, Girnun GD, Tou L, Szwaya JD, Mueller E, Xia K, et al. Hic-5 regulates an epithelial program mediated by PPARgamma. Genes Dev. 2005;19:362–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girnun GD, Naseri E, Vafai SB, Qu L, Szwaya JD, Bronson R, et al. Synergy between PPARgamma ligands and platinum-based drugs in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girnun GD, Smith WM, Drori S, Sarraf P, Mueller E, Eng C, et al. APC-dependent suppression of colon carcinogenesis by PPARgamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13771–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162480299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boros LG, Lerner MR, Morgan DL, Taylor SL, Smith BJ, Postier RG, et al. [1,2-13C2]-D-glucose profiles of the serum, liver, pancreas, and DMBA-induced pancreatic tumors of rats. Pancreas. 2005;31:337–43. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000186524.53253.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vizan P, Boros LG, Figueras A, Capella G, Mangues R, Bassilian S, et al. K-ras codon-specific mutations produce distinctive metabolic phenotypes in NIH3T3 mice [corrected] fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5512–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Errico I, Salvatore L, Murzilli S, Lo Sasso G, Latorre D, Martelli N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-{gamma} coactivator 1-{alpha} (PGC1{alpha}) is a metabolic regulator of intestinal epithelial cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016354108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chajes V, Cambot M, Moreau K, Lenoir GM, Joulin V. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha is essential to breast cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5287–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD, et al. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6379–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Griffiths B, Cully M, Wu M, Leevers S, et al. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab. 2008;8:224–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber SN, Emter R, Hock MB, Knutti D, Cardenas J, Podvinec M, et al. The estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) functions in PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308686101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mootha VK, Handschin C, Arlow D, Xie X, St Pierre J, Sihag S, et al. Erralpha and Gabpa/b specify PGC-1alpha-dependent oxidative phosphorylation gene expression that is altered in diabetic muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6570–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401401101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun P, Sehouli J, Denkert C, Mustea A, Konsgen D, Koch I, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor-related receptors, a subfamily of orphan nuclear receptors, as new tumor biomarkers in ovarian cancer cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83:457–67. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0639-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ariazi EA, Clark GM, Mertz JE. Estrogen-related receptor alpha and estrogen-related receptor gamma associate with unfavorable and favorable biomarkers, respectively, in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6510–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein RA, Chang CY, Kazmin DA, Way J, Schroeder T, Wergin M, et al. Estrogen-related receptor alpha is critical for the growth of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8805–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chisamore MJ, Wilkinson HA, Flores O, Chen JD. Estrogen-related receptor-alpha antagonist inhibits both estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast tumor growth in mouse xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:672–81. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki T, Miki Y, Moriya T, Shimada N, Ishida T, Hirakawa H, et al. Estrogen-related receptor alpha in human breast carcinoma as a potent prognostic factor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4670–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhajda FP, Pizer ES, Li JN, Mani NS, Frehywot GL, Townsend CA. Synthesis and antitumor activity of an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3450–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050582897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winter-Vann AM, Casey PJ. Post-prenylation-processing enzymes as new targets in oncogenesis. Nature reviews. 2005;5:405–12. doi: 10.1038/nrc1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nature reviews. 2009;9:550–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sun X, Zheng Y, Roman J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta induces lung cancer growth via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator gamma-1alpha. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:325–31. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0197OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Shiota M, Yokomizo A, Tada Y, Inokuchi J, Tatsugami K, Kuroiwa K, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha interacts with the androgen receptor (AR) and promotes prostate cancer cell growth by activating the AR. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:114–27. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deblois G, Giguere V. Functional and physiological genomics of estrogen-related receptors (ERRs) in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1032–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher KW, Das B, Kortum RL, Chaika OV, Lewis RE. Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) Regulates PGC1{alpha} and Estrogen-Related Receptor {alpha} To Promote Oncogenic Ras-Dependent Anchorage-Independent Growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2453–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05255-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiraby C, Hazen BC, Gantner ML, Kralli A. Estrogen-Related Receptor gamma promotes mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and suppresses breast tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasbach KA, Gupta RK, Ruas JL, Wu J, Naseri E, Estall JL, et al. PGC-1{alpha} regulates a HIF2{alpha}-dependent switch in skeletal muscle fiber types. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016089107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valle I, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Arza E, Lamas S, Monsalve M. PGC-1alpha regulates the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:562–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jager S, et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Vigneri R. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1103–23. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giovannucci E, Michaud D. The role of obesity and related metabolic disturbances in cancers of the colon, prostate, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2208–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.