Abstract

The melanocortin signaling system is integral in regulating energy homeostasis. The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) activates several signaling pathways in performance of this function. The effect of MC4R on insulin-stimulated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a cellular energy sensor, signaling was investigated. The GT1-1 cell line which expresses MC4R expression was utilized. mTOR signaling was measured by Western blotting analysis using Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) antibody. NDP-MSH dose-dependently enhanced insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation. The MC4R antagonist SHU9119 blocked this effect, demonstrating specificity. The protein kinase A - cyclic AMP pathway and the MAP kinase pathway were not involved in NDP-MSH actions on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation. In contrast, the AMP-activated protein kinase agonist, AICAR, attenuated this effect. MC4R activation potentiates insulin-stimulated mTOR signaling via the AMPK pathway.

Keywords: Melanocortin-4 receptor, NDP-MSH, mammalian target of rapamycin, AMPK

1. Introduction

The melanocortin signaling system has an important role in regulating energy homeostasis. The melanocortin system consists of the prohormone proopiomelanocortin (POMC), its derivative melanocortin peptides (α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone, and the endogenous melanocortin peptide antagonists, agouti and agouti-related peptide (AgRP). In hypothalamic control of caloric intake, the relevant components of the melanocortin system include POMC-derived peptides, the antagonist AgRP, and melanocortin receptor types 3 and 4 [11, 21]. In addition to an important role in energy homeostasis, the melanocortin system also exerts a variety of other neural effects [3, 6].

Because of the crucial role of the melanocortin system in energy homeostasis, its signaling pathways have been extensively examined. The conventional understanding of melanocortinergic signaling involves the cyclic AMP transduction pathway via a Gs protein and adenylyl cyclase. Melanocortin receptor activation has also been associated with changes in intracellular Ca2+ and inositol trisphosphate levels and with the protein kinase C pathway. Recently, melanocortin receptor activation has been reported to cause extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation [3, 9].

In neuronal circuits which regulate feeding, melanocortin peptides also interact with other factors, either acting as intrinsic elements of signaling pathways or potentiating peripherally derived signals. For example, melanocortin receptor subtype 4 signaling is also involved in CCK-mediated satiety, and activation of the ERK pathway by melanocortin receptors is necessary for peripheral cholecystokinin (CCK) to suppress food intake [12, 30]. Intracerebroventricular administration of the melanocortin agonist, MT II, increases insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese rats [2]. In a previous study, we have reported that melanocortin receptor subtype 4 (MC4R) activation synergistically increases insulin-stimulated AKT signaling and glucose uptake in neuronal cells [4].

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase, plays an important role in central neuronal control of nutrient intake and energy balance. mTOR has a ubiquitous distribution in brain, and phosphorylation of mTOR has been demonstrated in hypothalamus, hippocampus, thalamus, and cortex [7]. mTOR signals through mTOR signaling complexes (TORCs), and the TORC1 specific inhibitor, rapamycin, blocked the anorexigenic effects of leucine or leptin [7]. Absence of the mTOR downstream target ribosomal protein S6 (S6) kinase 1 protects against diet-induced obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in mice [33]. These studies indicate that brain mTOR signaling is involved in regulating nutrient intake and energy metabolism. In the present study, MC4R activation potentiated insulin-stimulated mTOR signaling, via a mechanism that involves AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals and Antibodies

NDP-MSH (α-MSH analogue, [Nle4, D-Phe7] α-MSH) and SHU-9119 were purchased from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA). The ERK1/2-specific inhibitor, PD98059, was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR(7C10), p-AMPK alpha (Thr172) antibody, and AICAR was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA). Insulin, RP-cAMP, and β-actin antibody and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2 Cell culture

GT1-1 cells (a generous gift from Dr. Richard I. Weiner, University of California-San Francisco) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing 100 U / ml penicillin and 100 U / ml streptomycin. Cells were plated on 100 mm dishes and maintained at 37°C in a water-saturated atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

2.3 Assay of phosphorylation of mTOR

Cells were seeded on 6 well plates and cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10 % FBS for 18 h. The media was then replaced with serum-free DMEM and incubated overnight. For studies with inhibitors or activators of signaling pathways, cells were treated with pathway inhibitors, activators or vehicle for 1 h before various treatments.

After treatment, the media were removed and cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline solution and lysed with a buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM beta-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF]. Lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4°C for 10 min, and supernatants were retained. The protein content of supernatants was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (Richmond, CA).

2.4 Western blotting

Protein samples from cell lysates (20–30 μg) were subjected to electrophoretic separation on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (BioRad) and then transferred onto Immobilon™-P PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Blots were blocked at room temperature for 1 h in 5% milk in TBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) and then incubated overnight in Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) antibody diluted 1/1000 in 5 % BSA. Membranes were washed three times in TBS-Tween (0.05%) and then incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody, diluted 1/5000 in 5% TBS-Tween (0.05%). Detection was performed using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

2.5 Signaling pathways

In order to investigate the possible signal pathways involved in the potentiation of insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation by NDP-MSH, the cAMP pathway inhibitor RP-cAMP, the MAP kinase inhibitor PD98059, and AMPK pathway activator AICAR were used.

2.6 Data analysis

For Western blots, analysis of densitometry was performed using Kodak 1D 3.6 software (Eastman Kodak, New Haven, CT). Data was analyzed using Graphpad Prism 4.0 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA), and expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences were analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. A value of p < 0.05 was taken as significant.

3. Results

3.1 NDP-MSH enhances insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation

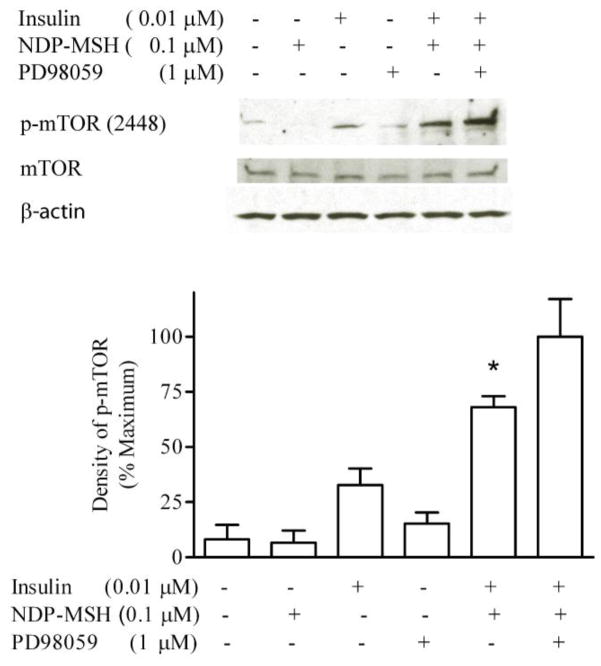

The GT1-1 cell line was established from a hypothalamic tumor induced by targeted expression of the oncogene encoding simian virus 40 T antigen to GnRH neurons in a transgenic mouse. The cell line is highly differentiated and expresses MC4R [3, 19]; the cells also are responsive to insulin [4]. Insulin dose-dependently stimulated m-TOR phosphorylation; NDP-MSH alone did not significantly induce mTOR phosphorylation. However, NDP-MSH significantly enhanced insulin-induced mTOR phosphorylation. As showed in Figure 1A, combination of 0.1 μM DNP-MSH with 0.01 μM insulin in GT1-1 cells increased mTOR phosphorylation (55 %); relative to 0.1 μM insulin alone (30 %). These results were also observed in HEK cells expressing MC4R (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. NDP-MSH enhances insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation.

GT1-1 and HEK 293 cells were deprived of serum overnight. Cells were incubated with insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. m-TOR phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. The films were scanned, and the band of highest density Western blot was defined as 100%. Experiments were repeated in GT1-1 cells four times (A), and twice in HEK cells (B). * p < 0.05 vs. insulin 0.01 μM; + p < 0.05 vs. insulin 0.1 μM.

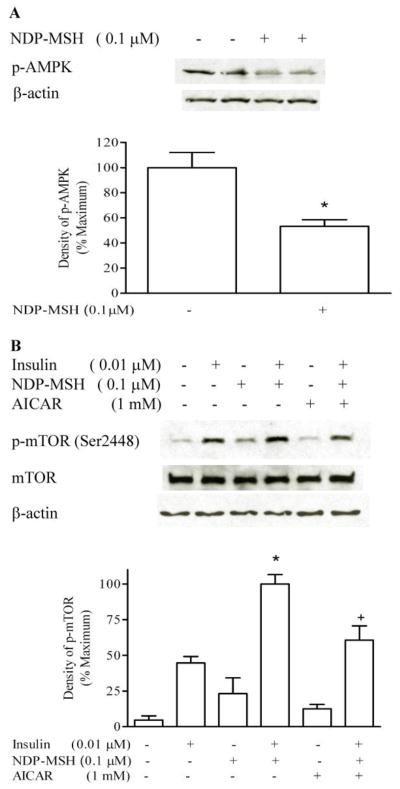

The melanocortin receptor antagonist SHU9119 alone did not significantly affect mTOR phosphorylation, but inhibited the effect of NDP-MSH on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation, with 0.1 μM SHU9119 blocking the effect of DNP-MSH by 74%, demonstrating that this effect is a MC4R-mediated process (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Melanocortin receptor antagonist inhibits NDP-MSH effects.

GT1-1 cells were deprived of serum overnight. Cells were incubated with insulin, NDP-MSH or SHU9119 for 20 minutes. m-TOR phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. The films were scanned, and the band of highest density was defined as 100%. * p < 0.05 vs. insulin; + p < 0.05 vs. insulin plus NDP-MSH, n=3.

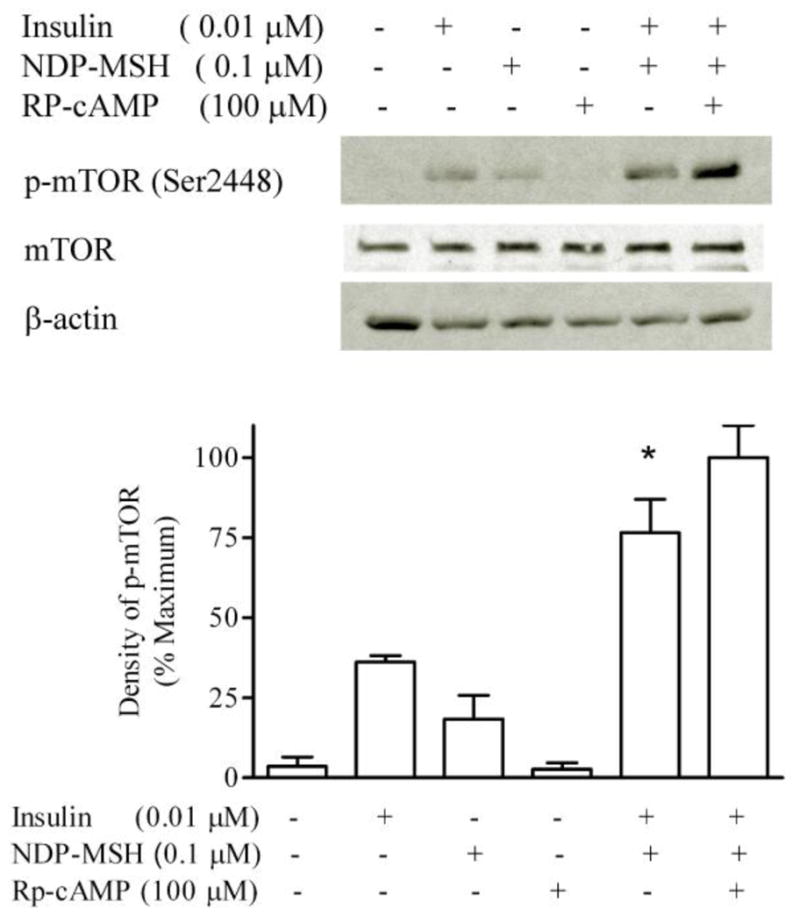

3.2 Effect of PKA-cAMP pathway on potentiation of insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation by NDP-MSH

GT1-1 cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM overnight. Serum-starved cells were preincubated with 100 μM Rp-cAMPs for 1 hour, and then treated with insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. There were no significant difference between the Rp-cAMPs treated and control groups, indicating that the cAMP pathway does not participate in the potentiation by NDP-MSH of insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of Rp-cAMPs on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation.

GT1-1 cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM overnight. Cells were preincubated for 1 h with Rp-cAMPs (100 μM), and then exposed to insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. m-TOR phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. * p < 0.05 vs. insulin, n=3.

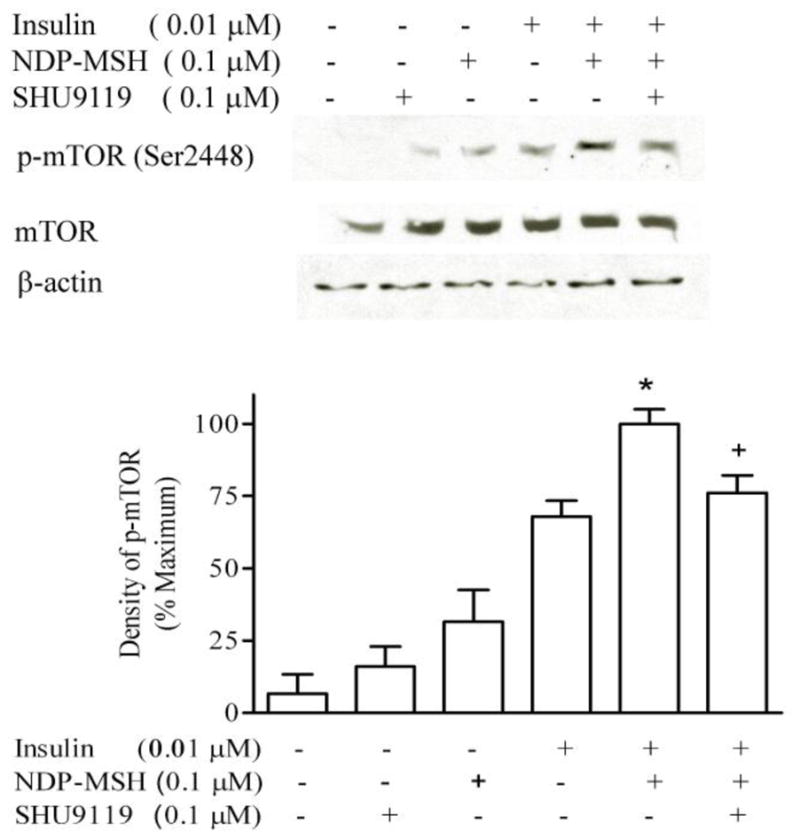

3.3 Effects of MAP kinase signal pathway

GT1-1 cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM overnight. Serum-starved cells were preincubated with 1 μM PD98059 for 1 hour, and then exposed to insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. PD98059 did not alter the effect of NDP-MSH on the insulin-simulated mTOR phosphorylation, compared to the group not exposed to PD98059, indicating that the MAP kinase pathway is not involved in the interaction between NDP-MSH and insulin (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of MAP kinase inhibition on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation.

Cells were preincubated for 1 h with PD98059, and then exposed to insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. m-TOR phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. * p < 0.05 vs. insulin, n=3.

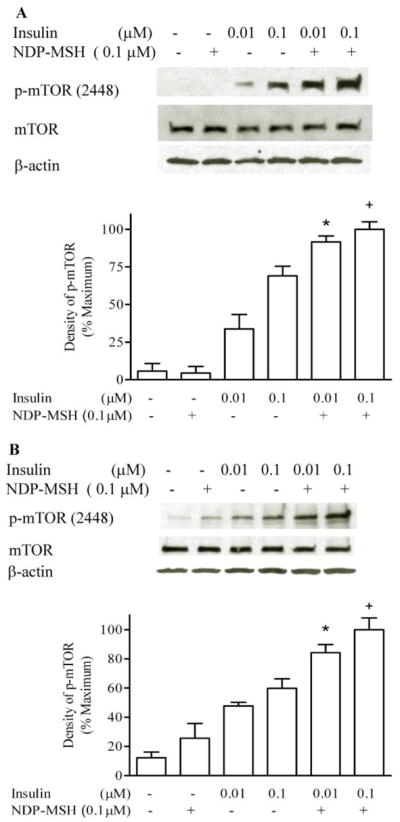

3.4 Effect of AMPK activator AICAR on mTOR phosphorylation

GT1-1 cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM overnight. Serum-starved cells were incubated with 0.1 μM NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. NDP-MSH inhibited the AMPK phosphorylation (Figure 5A). Serum-starved cells were preincubated with 1 mM AICAR for 1 hour, then treated with insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. AICAR treatment significantly decreased the effect of NDP-MSH on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation (insulin plus DNP-MSH 100 ± 9.2 %, AICAR-treated 58 ± 11 %, insulin alone, 45 ± 6%) (Figure 5 B).

Figure 5. NDP-MSH inhibits AMPK phosphorylation, and AMPK activator decreases potentiation by NDP-MSH of insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation.

GT1-1 cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM overnight. Cells were treated with NDP-MSH for 20 minutes and p-AMPK was detected (A). Cells were preincubated for 1 h with AICAR, and then treated with insulin and NDP-MSH for 20 minutes. m-TOR phosphorylation was determined by Western blotting. * p < 0.05 vs. Insulin; + p < 0.05 vs. insulin plus NDP-MSH (B).

4. Discussion

The principal finding of the current study is that melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) activation potentiates insulin-stimulated mTOR signaling via the AMPK pathway. There are four separate observations that support this conclusion: 1) insulin dose-dependently increased mTOR phosphorylation; 2) this effect was significantly increased by the MC4R agonist, NDP-MSH; 3) the actions of NDP-MSH were blocked by an antagonist of the MC4R; 4) the effects were also sensitive to an activator of AMPK, but not to agents active in cAMP or MAPK signaling pathways.

The melanocortin-4 receptor is a member of a family of seven transmembrane receptors, consisting of five subtypes, MC1-MC5R [13–15, 24]. Both MC3R and MC4R have important roles in central control of energy homeostasis. Areas of the brain with high levels of MC4R expression include the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, isocortex and nucleus of the solitary tract [28]. MC4R is a strong candidate for appetite regulation since it is highly expressed in the hypothalamus and has a strong affinity for α-MSH. Local injection of MC4 receptor agonists such as α-MSH into the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) causes reduction in food intake in mice and rats [35]. When MC4R antagonists such as AgRP are injected directly into the PVN, feeding is stimulated.

In addition to the central nervous system, melanocortin receptors are also expressed in peripheral tissues. Melanocortin receptor expression has been localized to placenta, gastrointestinal tract, heart and monocytes [5, 13]. This diverse localization suggests activities beyond energy homeostasis, and a variety of biological functions have been reported [4, 16, 32] .

Most studies of melanocortin receptor signaling have focused upon adenylyl cyclase and inositol phospholipid- Ca2+- mediated signaling systems [1, 23]. Recent studies have demonstrated that MC4R activation may also induce MAP kinase activation. In vitro, melanocortin peptides activated MAPK in COS-1 cells, in CHO-K1 cells transfected with MC4R [9, 34] and in GT1-1 cells that endogenously express MC4R receptor [3]. In vivo, central administration of the melanocortin agonist MTII increased phospho-MAPK-immunoreactivity in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat [30]. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the solitary nucleus is required for suppression of food intake caused by administration of exogenous cholecystokinin [31]. Activation of the ERK pathway is also necessary for inhibition of nutrient intake by intracerebroventricularly administered MT II [30].

Insulin signaling involves a wide variety of signaling pathways such as IRS, AKT, Pten, Pdk1, and mTOR. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase. Emerging evidence indicates that mTOR is critical for regulation of energy balance by coordinating cellular energy levels with the status of overall energy supply and expenditure. mTOR is regulated by cellular levels of ATP [10]. AMPK is also regulated by intracellular AMP/ATP ratios, and AMPK mediates mTOR signaling [18, 26]. Leucine and a high-protein diet decrease AMPK and increase mTOR activity in the hypothalamus [27]. AMPK is also regulated by melanocortin receptors [17]; melanocortin receptor agonist administration decreases AMPK activity in the paraventricular area of the hypothalamus, whereas AGRP increases AMPK activity [22]. AICAR can enter cells and be phosphorylated to an AMP anolog, which allosterically activates AMPK and an upstream AMPK kinase with further activation of AMPK [8]. The present experiments showed that AICAR, an AMPK activator, decreases the potentiation by NDP-MSH of insulin-stimulated mTOR signaling, implicating AMPK activation in mTOR phosphorylation.

Others have reported that forskolin-generated cAMP in pancreatic islets resulted in activation of mTOR, and an inhibitor partially blocked glucose-induced S6K1 phosphorylation, a mTOR down stream effector [20]. Our study, by using cAMP pathway inhibitor RP-cAMP, showed that NDP-activated cAMP signal does not participate in potentiation by NDP-MSH of insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation. In some cancer cells, the ERK pathway particiapates in the activation of mTOR signaling [29]. Because NDP-MSH stimulates the activation of ERK1/2, we used the ERK inhibitor PD98059 to investigate the possible role of ERK pathway in the synergistic effect of NDP-MSH and insulin on mTOR phosphorylation. Our results demonstrated that ERK pathway is not involved in this process.

Regulation of feeding is a complex process, with multiple factors involved. Some actions of satiety or orexigenic factors are additive in regulating ingestive functions. Leptin and insulin potentiate the satiating effect of CCK [25]. Melanocortin has been reported to potentiate leptin-induced STAT3 signaling [36]. A melanocortin agonist increases insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese rats [2]. In prior studies we have reported that MC4R activation synergistically increases insulin-stimulated AKT signaling and glucose uptake in hypothalamic cells [4]. The present study shows that MC4R increases insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation, a cellular energy sensor.

Research Highlights.

Melanocortin receptor 4 agonist NDP-MSH potentiates insulin-stimulated mTOR Phosphorylation in GT1-1 cells

cAMP pathway inhibitor Rp-cAMP and MAP kinase pathway inhibitor PD98059 are not involved in NDP-MSH actions on insulin-stimulated mTOR phosphorylation.

AMP-activated protein kinase agonist AICAR attenuates the effect of NDP-MSH on insulin-stimulated mTOR Phosphorylation.

Abbreviations

- NDP-MSH

[Nle4, DPhe7]-α-melanocyte stimulating hormone

- p MAPK

mitogen-activated-protein kinase

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2

- MCR

melanocortin receptor

- SHU9119

Ac-Nle-c[Asp-His-D-Nal-Arg-Trp-Lys]-NH2

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adan RA, Cone RD, Burbach JP, Gispen WH. Differential effects of melanocortin peptides on neural melanocortin receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;46:1182–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banno R, Arima H, Hayashi M, Goto M, Watanabe M, Sato I, et al. Central administration of melanocortin agonist increased insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese rats. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai B, Li JY, Zhang W, Newman E, Ammori J, Mulholland MW. Melanocortin-4 receptor-mediated inhibition of apoptosis in immortalized hypothalamic neurons via mitogen-activated protein kinase. Peptides. 2006;27:2846–57. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai B, Li JY, Zhang W, Wang H, Mulholland MW. Melanocortin-4 receptor activation inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase activity and promotes insulin signaling. Peptides. 2009;30:1098–104. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhajlani V. Distribution of cDNA for melanocortin receptor subtypes in human tissues. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;38:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cone RD. Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocrine Reviews. 2006;27:736–49. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, et al. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science. 2006;312:927–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1124147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagher Z, Ruderman N, Tornheim K, Ido Y. The effect of AMP-activated protein kinase and its activator AICAR on the metabolism of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:112–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels D, Patten CS, Roth JD, Yee DK, Fluharty SJ. Melanocortin receptor signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase in vitro and in rat hypothalamus. Brain Research. 2003;986:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan W, Boston BA, Kesterson RA, Hruby VJ, Cone RD. Role of melanocortinergic neurons in feeding and the agouti obesity syndrome. Nature. 1997;385:165–8. doi: 10.1038/385165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan W, Ellacott KL, Halatchev IG, Takahashi K, Yu P, Cone RD. Cholecystokinin-mediated suppression of feeding involves the brainstem melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:335–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gantz I, Konda Y, Tashiro T, Shimoto Y, Miwa H, Munzert G, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel melanocortin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8246–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gantz I, Miwa H, Konda Y, Shimoto Y, Tashiro T, Watson SJ, et al. Molecular cloning, expression, and gene localization of a fourth melanocortin receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:15174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gantz I, Shimoto Y, Konda Y, Miwa H, Dickinson CJ, Yamada T. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a fifth melanocortin receptor. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;200:1214–20. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarini S, Schioth HB, Mioni C, Cainazzo M, Ferrazza G, Giuliani D, et al. MC(3) receptors are involved in the protective effect of melanocortins in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced arrhythmias. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:177–82. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson DS, Summers RJ, Bengtsson T, Hutchinson DS, Summers RJ, Bengtsson T. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase activity by G-protein coupled receptors: potential utility in treatment of diabetes and heart disease. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;119:291–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn BB, Myers MG, Jr, Kahn BB, Myers MG., Jr mTOR tells the brain that the body is hungry. Nat Med. 2006;12:615–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0606-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khong K, Kurtz SE, Sykes RL, Cone RD. Expression of functional melanocortin-4 receptor in the hypothalamic GT1–1 cell line. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:193–201. doi: 10.1159/000054686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon G, Marshall CA, Pappan KL, Remedi MS, McDaniel ML. Signaling elements involved in the metabolic regulation of mTOR by nutrients, incretins, and growth factors in islets. Diabetes. 2004;53 (Suppl 3):S225–32. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks DL, Hruby V, Brookhart G, Cone RD. The regulation of food intake by selective stimulation of the type 3 melanocortin receptor (MC3R) Peptides. 2006;27:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue B, et al. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428:569–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mountjoy KG, Kong PL, Taylor JA, Willard DH, Wilkison WO. Melanocortin receptor-mediated mobilization of intracellular free calcium in HEK293 cells. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:11–9. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Cone RD. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science. 1992;257:1248–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1325670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters JH, Simasko SM, Ritter RC. Modulation of vagal afferent excitation and reduction of food intake by leptin and cholecystokinin. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:477–85. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polak P, Hall MN. mTOR and the control of whole body metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Fernandes MF, Rocco SA, Marin RM, Morari J, et al. A central role for neuronal AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in high-protein diet-induced weight loss. Diabetes. 2008;57:594–605. doi: 10.2337/db07-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roselli-Rehfuss L, Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Low MJ, Tatro JB, et al. Identification of a receptor for gamma melanotropin and other proopiomelanocortin peptides in the hypothalamus and limbic system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:8856–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–30. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton GM, Duos B, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Melanocortinergic modulation of cholecystokinin-induced suppression of feeding through extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in rat solitary nucleus. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3739–47. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutton GM, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway in solitary nucleus mediates cholecystokinin-induced suppression of food intake in rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10240–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2764-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taherzadeh S, Sharma S, Chhajlani V, Gantz I, Rajora N, Demitri MT, et al. alpha-MSH and its receptors in regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by human monocyte/macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1289–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, Picard F, Joaquin M, Sticker M, et al. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2004;431:200–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vongs A, Lynn NM, Rosenblum CI. Activation of MAP kinase by MC4-R through PI3 kinase. Regul Pept. 2004;120:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth MM, Olszewski PK, Yu C, Levine AS, Giraudo SQ. Paraventricular hypothalamic alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and MTII reduce feeding without causing aversive effects. Peptides. 2001;22:129–34. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Wu X, He Y, Kastin AJ, Hsuchou H, Rosenblum CI, et al. Melanocortin potentiates leptin-induced STAT3 signaling via MAPK pathway. J Neurochem. 2009;110:390–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]