Abstract

Noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus project throughout the cerebral cortex and multiple subcortical structures. Alterations in the locus coeruleus firing are associated with vigilance states and with fear and anxiety disorders. Brain ionotropic type A receptors for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) serve as targets for anxiolytic and sedative drugs, and play an essential regulatory role in the locus coeruleus. GABAA receptors are composed of a variable array of subunits forming heteropentameric chloride channels with different pharmacological properties. The γ2 subunit is essential for the formation of the binding site for benzodiazepines, allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors that are clinically often used as sedatives/hypnotics and anxiolytics. There are contradictory reports in regard to the γ2 subunit’s expression and participation in the functional GABAA receptors in the mammalian locus coeruleus. We report here that the γ2 subunit is transcribed and participates in the assembly of functional GABAA receptors in the tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neuromelanin-containing neurons within postmortem human locus coeruleus as demonstrated by in situ hybridization with specific γ2 subunit oligonucleotides and Autoradiographic assay for flumazenil-sensitive [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding to benzodiazepine sites. These sites were also sensitive to the α1 subunit-preferring agonist zolpidem. Our data suggest a species difference in the expression profiles of the α1 and γ2 subunits in the locus coeruleus, with the sedation-related benzodiazepine sites being more important in man than rodents. This may explain the repeated failures in the transition of novel drugs with a promising neuropharmacological profile in rodents to human clinical usage, due to intolerable sedative effects.

Keywords: GABAA receptor subunits, Locus coeruleus, Benzodiazepine binding

The locus coeruleus (LC) is the major source of noradrenaline containing neurons in the brain. It is ventrolateral to the fourth ventricle in the pons. Increased firing of the LC is associated with a state of increased vigilance, stress exposure, fear, and anxiety. Subjective sensations of anxiety and physical symptoms associated with panic disorder can be elicited in healthy human subjects following noradrenaline administration (reviewed in [6,7]). Insomnia is frequently associated with stress and anxiety. The LC has been implicated as a component of the neural network regulating sleep and wakefulness, being active during the awake state and hence known as an arousal centre (reviewed in [27]). Hence, inhibition of the LC neurons might induce strong anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic effects.

The major GABAergic input source to the core of the LC is the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi, inhibiting the LC firing by activating presumably both pre- and postsynaptic GABAA receptors [12,15,26]. GABAA receptors are heteropentameric ligand-gated anion channels, composed of variable combinations of α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, θ and π subunits, forming functionally diverse receptors. These receptors differ in their channel kinetics, rate of desensitization and affinity for GABA and allosteric modulators (reviewed in [23]). The rare subunits ε and θ are highly enriched in the rodent and primate LC [5,24,25,29]. The unique repertoire of GABAA receptor subunits in a specific neuronal network regulating particular brain functions could provide an opportunity to develop subunit selective drugs acting on selected neuronal populations.

Benzodiazepines are generally prescribed as anxiolytic and sedative–hypnotic drugs. The GABAA receptor γ subunit, in particular the γ2 variant, is essential for benzodiazepine binding and efficacy [18]. Some studies have suggested the presence of γ2 subunit mRNA expression in the LC region of rats [8,9], not showing the specific expression in the noradrenaline neurons. Fritschy and Mohler [13] have shown an immunohistochemical signal for γ2 subunit in the rat LC. However, many rodent studies do not find the γ2 subunit gene expression in the LC (e.g., [2,11,20]), suggesting that LC is insensitive to benzodiazepines. Accordingly, the LC would not be implicated in the direct mediation of anxiolysis or sedation by these drugs. However, there might be considerable species differences in the effects of benzodiazepines in the LC. The present study was aimed to investigate the expression of GABAA receptor γ2 subunit and benzodiazepine binding ability in the human LC. After this study was submitted, Waldvogel et al. [28] have demonstrated γ2 subunit immunoreactivity in the pigmented neurons of human LC.

Postmortem brain material for normal human brain was obtained from the brain tissue collection of the Section on Neuropathology of the Clinical Brain Disorders Branch, Genes Cognition and Psychosis Program of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health under a protocol approved by the IRB of the NIMH, with informed consent of the next of kin. The collection, screening, and analysis of the subjects used in this study have been previously described by Lipska et al. [16]. These samples of LC and cerebellar cortex (2 females, 3 males, average age 30±12.6 years) were used for immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization and ligand autoradiographic procedures.

The cause of death was determined by a pathologist at autopsy and the toxicology data were obtained on each case with an assay of either brain or blood, depending upon availability (Table 1). The interval between death and tissue collection ranged from 16 to 50.5 h. Immediately after autopsy, the pons and cerebellar cortex were cut into 2–3cm thick slabs, flash frozen in a slurry of dry ice and isopentane, and kept at −80°C. Fourteen-m-thick sections were cut from the slabs of pons and cerebellar cortex with a Leica CM 3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Benheim, Germany) at −20°C for the histochemical experiments. The sections were thaw-mounted onto gelatin-coated (for immunohistochemistry and ligand autoradiography) or SuperFrost (for in situ hybridization histochemistry) object classes (Menzel Gläser) and stored frozen at −70°C.

Table 1.

Demographic data of subjects.

| Subject (ID) | Sex | Age(years) | PMIa(h) | Cause of death | Toxicology | Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1228 | Male | 49 | 50.5 | Natural | NDDb | Negative |

| 1548 | Male | 37 | 26 | Natural | NDD | Negative |

| 1550 | Male | 20 | 32 | Natural | Ethanol | Negative |

| 1558 | Female | 23 | 17.5 | Natural | NDD | Negative |

| 1563 | Female | 21 | 18 | Natural | Diphenhydramine | Negative |

Postmortem interval.

No drugs detected.

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining was performed to localize the LC on the sections, and adjacent sections were used for in situ hybridization and ligand autoradiography. Sections were fixed in cold acetone for 5min and washed briefly in 1×phosphatebuffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Then the sections were incubated at room temperature with the 1:25 dilution of primary rabbit anti-TH affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (AB152; Chemicon International, Temecula, USA), the 1:50 dilution of secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit goat IgG (PK-6105; Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector laboratories) and with the avidin/biotinylated horseradish peroxidase enzyme complex ABC (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector laboratories) for 4min each and briefly rinsed with 1× PBS between each step. After the color development with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Vector laboratories) for 60s, the sections were rinsed in H2O, and then dehydrated in 70%, 95% and 100% ethanol (30s each) and xylene (twice for 5min each). Finally, glass cover slips (Menzel-Gläser) were mounted on the sections by gently laying them on to a drop of mounting medium. Negative controls were carried out in the absence of the primary antibody. The LC sections were scanned (Epson expression 1680 Pro) with digital manipulation (shadow 179, gamma 2.89, highlight 215) in order to sharply elicit the TH positive cells that were clearly observable with a light microscope.

For in situ hybridization experiments, the air-dried LC-containing and cerebellar cortical sections from one subject (ID: 1550) were fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 5min. The sections were washed in 1× PBS at room temperature for 5min, dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 5min and stored in 95% ethanol at 4°C until used. Two different antisense DNA oligonucleotide probes (45-mers) complementary to the human GABAA receptor γ2 subunit mRNA sequence (nucleotides 1442–1486 and 1695–1739; Gen-Bank accession number NM 198904) and analogous sense probes were synthesized (Oligomer Oy, Helsinki, Finland). Both antisense probes displayed 100% query coverage with transcript variants 1, 2 and 3 (GenBank accession numbers NM 198904.1, NM 000816.2 and NM 198903.1, respectively). Poly[35S]dA ([35S]dATP from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) tails were added to the 3’- ends of the probes by deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by Illustra ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Columns (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The labelling efficiency (200 000–330 000 cpm/µl) was determined by a scintillation counter. The labelled probe was diluted to 0.06 fmol/µl with hybridization buffer (containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulphate, 4× SSC). Nonspecific controls for the antisense probes were produced by adding 100-fold excess of unlabelled probes. The hybridization occurred under glass cover slips (Menzel-Gläser) overnight at 42°C. Finally, the slides were washed in 1× SSC at room temperature for 10 min, in 1× SSC at 55°C for 30 min, and 1× SSC, 0.1× SSC, 70% EtOH and 95% EtOH at room temperature for 1min each. The sections were then air-dried and exposed to BioMax MR film (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY, USA) for up to a week. The films were scanned for images (Epson expression 1680 Pro). The sections were then processed for emulsion autoradiography, by dipping them in Kodak autoradiography emulsion (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY, USA) diluted in 600mM ammonium acetate (1:1 volume) in the 42°C water bath, air-dried overnight in the dark and exposed in a light-tight slide box at 4°C for 6 weeks. Thereafter, the sections were developed at 15°C in Kodak D-19 Developer for 3min, water for 30s, and Kodak fixer for 5min. The sections were then washed twice in water for 5min and air-dried over-night at room temperature. The dry sections were counterstained by 0.125% thionin, rinsed with water, dehydrated in ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%) and xylene. At the end, the cover slips were mounted on the sections. Conventional transmitted and darkfield images were acquired using Olympus AX70 microscope with UPlanF1 20×/0.50 NA or PlanApo 60×/1.40 NA Oil objectives.

[3H]Ro 15-4513 autoradiographic binding assay (modified from [21]) was performed to label the benzodiazepine binding sites and to assess the zolpidem sensitivity of the receptors. Brain sections from five subjects (IDs: 1228, 1548, 1550, 1558 and 1563) were pre-incubated in ice-cold 50mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 120mMNaCl for 15 min. The final incubation was performed in the pre-incubation buffer containing 15nM (160 cpm/l) [3H]Ro 15-4513 (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) at 4°C for 1 h. Displacement of [3H]Ro 15-4513 was studied in the presence of 1nM to 10M zolpidem. The nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10M flumazenil. The sections were then washed in ice-cold pre-incubation buffer twice for 1min, dipped in ice-cold distilled water, air-dried at room temperature and exposed with 3H-plastic standards (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) to BAS-TR 2040 imaging plate (Fujifilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan) for up to 2–3 days. Binding density was measured as optical density values (SCION IMAGE; Wayne Rasband, NIMH, Bethesda, MD) from digitalized images scanned by the FLA-9000 Starion image scanner (Fujifilm). With the 3H-standards exposed simultaneously with the sections as the reference, the binding values were converted to nCi/mg for [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding. The nonspecific binding values were negligible (Fig. 2). Displacement curves in the presence of zolpidem were fitted to log(inhibitor)–response curves with a variable slope using Prism program (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

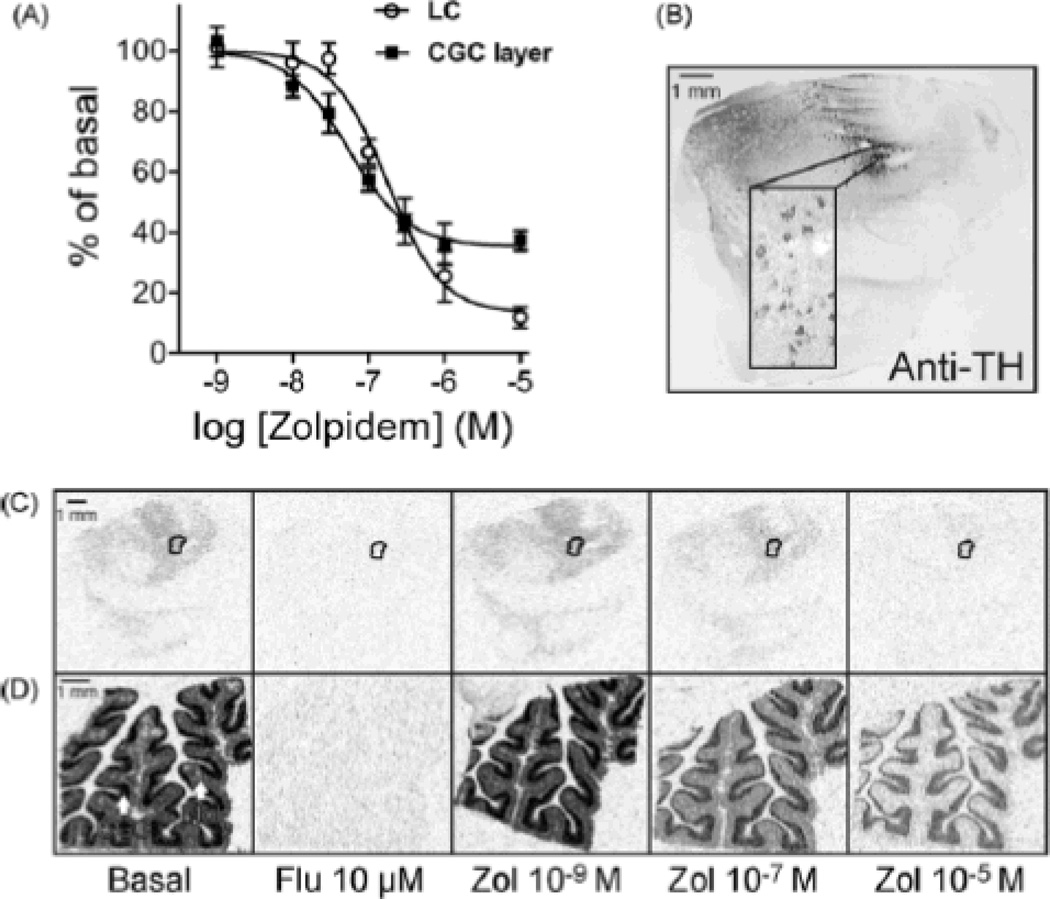

Fig. 2.

[3H]Ro 15-4513 autoradiography was used to reveal the benzodiazepine binding sites and their sensitivity to zolpidem. (A) Values for the [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding in the presence of 1nM to 10M zolpidem are presented as percent from the corresponding basal [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding (% of basal) in the locus coeruleus (LC) and cerebellar granule cell layer (CGC). Data are mean±S.E.M., n = 5. The curves are from curve fits using nonlinear regression analysis. (B) The LC was identified by TH immunostaining (anti-TH) in separate sections and was used as a template for quantitating the optical density values of the film images within the correct anatomical location for the adjacent sections. Autoradiographic images of the [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding at the basal level, and in the presence of specified concentrations of flumazenil (Flu; nonspecific binding) and zolpidem (Zol) (C) in the LC (encircled) and (D) in the cerebellar cortex. Mol, molecular layer of cerebellum.

The localization of the LC in pons sections was determined by immunostaining with anti-TH antibody (Figs. 1A and 2B). The TH immunostaining almost fully overlapped with endogenous neuromelanin-pigmented neurons. The TH immunoreactivity was absent in the negative controls, whereas the neuromelanin pigment was still present in the noradrenergic neurons.

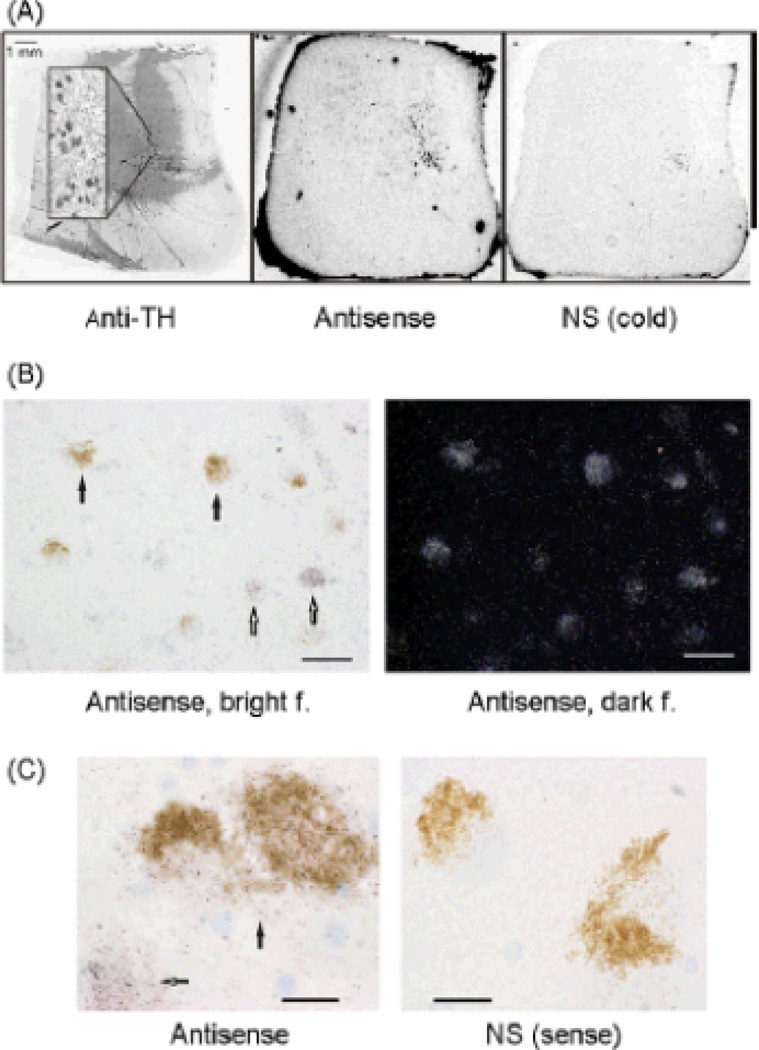

Fig. 1.

Expression of the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit mRNA in the human LC as revealed by in situ hybridization. (A) The LC was identified by TH immunostaining (anti-TH) in separate sections and was used as a template for detecting the optical densities of the film images within the proper location for the adjacent sections. The γ2mRNA was expressed in the LC as revealed by the antisense oligoprobe hybridization (antisense). The nonspecific control for the antisense probe was produced by adding 100-fold excess of unlabelled probe, which virtually abolished the signal (NS cold). (B) Emulsion autoradiography showing the γ2 gene expression at the cellular level. The γ2 mRNA was expressed over entire LC, including neuronal somas (both brown neuromelanin-pigmented somas labelled with solid arrows and nonpigmented somas labelled with open arrows) within the structure. This is illustrated by silver grain deposits produced by the antisense probe hybridization in transmitted brightfield (antisense, bright f.) and in reflected darkfield (antisense, dark f.) microscopy images. The scale bars are 60m. (C) On the left, silver grain deposits over pigmented soma(s) (solid arrow) and over a non-pigmented soma (open arrow) produced by the antisense probe hybridization. On the right, nonspecific control somas showing no silver grain deposits, after hybridization with the sense probe complementary to the antisense probe (NS sense) and emulsion autoradiography. Neuromelanin pigment was present in most neurons that were immunostained by TH antibody (not shown). The scale bars are 20m. show that zolpidem displays about 10-fold higher affinity.

Using in situ hybridization and film autoradiography, an obvious γ2 mRNA signal in the TH-defined LC (Fig. 1A) was revealed by the two antisense probes designed to hybridize to different locations of human GABAA receptor γ2 subunit mRNA. The emulsion autoradiography confirmed the positive signal at the cellular level. There was a high density of silver grains over the entire LC, including neuronal somas within the structure (Fig. 1B). Silver grain deposits were over both brown neuromelanin-pigmented and nonpigmented somas of LC neurons (Fig. 1B and C). The reliability of the present in situ hybridization was confirmed by control experiments with complementary sense probes (Fig. 1C) and competition hybridizations in the presence of excess unlabelled (cold) antisense probes (Fig. 1A). In these control experiments, the signal was only weakly detectable after the film exposure (Fig. 1A). After the emulsion autoradiography, the silver grains were absent in the negative controls (Fig. 1C) indicating that the faint signal on the film was an artifact. A strong expression of the γ2 subunit mRNA was detected in the cerebellar granule cell layer that served as a control for γ2 subunit expression (data not shown). Thus, we here provide evidence for the expression of GABAA receptor γ2 subunit mRNA in TH-positive neuromelanin-containing neurons of the human LC.

[3H]Ro 15-4513 autoradiography was performed to study whether the γ2 subunit is assembled in GABAA receptors within the human LC. The granule cell layer of the cerebellar cortex served as a control for benzodiazepine binding [1]. The LC was identified by TH immunostaining (anti-TH) (Fig. 2B), which was used as a regional template for quantifying the optical density values of the Autoradiographic images. [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding was clearly detected in the LC (18±1 nCi/mg, mean±S.E.M., n=5; Fig. 2C) and cerebellar granule cell layer (68±8 nCi/mg, n=5, Fig. 2D). Nonspecific binding was negligible as benzodiazepine-site antagonist flumazenil (10M) displaced all the binding in the sections (Fig. 2C and D). Thus, our results indicate that there are functional benzodiazepine binding sites at GABAA receptors in TH-positive neuromelanin-containing neurons of the human LC.

Zolpidem is a GABAA receptor α1 subunit-preferring benzodiazepine-site agonist [18], and exhibited approximately 3-fold higher affinity to the receptors in the cerebellar granule cell layer than to the receptors in the LC (Fig. 2). The IC50 values for zolpidem determined by displacement of [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding were 176nM (Hill slope −1.2) and 54nM (Hill slope −1.1) for the LC and cerebellar granule cell layer, respectively. Earlier studies show that zolpidem displays about 10-fold higher affinity to α1 subunit-containing receptors than to α2/3 subunit-containing receptors [14]. Since the cerebellar granule cells express α1 subunits without α2/3 subunits [30], our autoradiographic data suggest that the human LC GABAA receptors contain α1 subunits in addition to α2/3 subunits, but here we cannot confirm their localization to pigmented neurons. As zolpidem lacks the sensitivity to γ3 subunit-containing receptors [4,19], our results imply that GABAA receptors in the human LC contain γ2 subunits that form benzodiazepine binding sites. These results agree with the recent demonstration of γ2 and α1 subunit immunoreactivities in the human LC pigmented and non-pigmented neurons [28]. Some of the latter ones might still be TH-positive [10]. Zolpidem at high concentration (10M) displaced the [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding to 13% and 35% of the basal binding in the LC and cerebellar granule cell layer, respectively. In the cerebellar granule cell layer this relatively high residual [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding is known to arise from the α6 subunit-containing GABAA receptors that do not bind zolpidem [21]. In the LC, the minor residual [3H]Ro 15-4513 binding might result from the receptors containing α4 or α5 subunits.

Our data suggest a significant limitation in the use of rodents as a study tool in neuropharmacological research. The present results are interesting in terms of benzodiazepine binding in the human LC. The γ2 variant is fundamental for benzodiazepine affinity and efficacy [18]. In mouse models, α1 subunits are associated with the sedative components of the benzodiazepine action [22], whereas γ2 subunits are supposed to be responsible for the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines [17]. Given that human LC neurons express the α1 and α2/α3 subunits together with the γ2 subunit, produce zolpidem-sensitive benzodiazepine binding sites, and regulate the arousal state and anxiety-related symptoms, the LC may mediate the sedative and anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines in humans. Our data highlight the possibility of a species difference in the expression profile of the γ2 subunit in the LC, with the benzodiazepine sites of this brain structure being more important in man than in rodents. Anxioselective partial agonists in rodents may have adverse sedative effects in man arising from the expression of α1–γ2 subunit-containing benzodiazepine binding sites. This may explain the difficulties in translating the promising preclinical rodent-based results into clinical benefit in man (see e.g., [3]).

Acknowledgements

Aira Säisä is gratefully acknowledged for the invaluable technical aid, and Mika Hukkanen for expert help in producing microscope images. The work was supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (KSH, ERK) and the Academy of Finland (ERK).

References

- 1.Albin RL, Gilman S. Autoradiographic localization of inhibitory and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter receptors in human normal and olivopontocerebellar atrophy cerebellar cortex. Brain Res. 1990;522:37–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91574-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki T, Sato M, Kiyama H, Manabe Y, Tohyama M. Localization of GABAA receptor γ2-subunit mRNA-containing neurons in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1992;47:45–61. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90119-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atack JR. Anxioselective compounds acting at the GABAA receptor benzodiazepine binding site. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2003;2:213–232. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benke D, Honer M, Michel C, Mohler H. GABAA receptor subtypes differentiated by their γ -subunit variants: prevalence, pharmacology and subunit architecture. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1413–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnert TP, McKernan RM, Farrar S, le Bourdelles B, Heavens RP, Smith DW, Hewson L, Rigby MR, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Brown N, Wafford KA, Whiting PJ. θ, a novel γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:9891–9896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety. I. Preclinical studies. Synapse. 1996;23:28–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<28::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety. II. Clinical studies. Synapse. 1996;23:39–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<39::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldji C, Francis D, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. The effects of early rearing environment on the development of GABAA and central benzodiazepine receptor levels and novelty-induced fearfulness in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldji C, Tannenbaum B, Sharma S, Francis D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5335–5340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan-Palay V, Asan E. Quantitation of catecholamine neurons in the locus coeruleus in human brains of normal young and older adults and in depression. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;287:357–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CL, Yang YR, Chiu TH. Activation of rat locus coeruleus neuron GABAA receptors by propofol and its potentiation by pentobarbital or alphaxalone. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;386:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ennis M, Aston-Jones G. GABA-mediated inhibition of locus coeruleus from the dorsomedial rostral medulla. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:2973–2981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02973.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadingham KL, Wingrove P, Le Bourdelles B, Palmer KJ, Ragan CI, Whiting PJ. Cloning of cDNA sequences encoding human α2 and α3 gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor subunits and characterization of the benzodiazepine pharmacology of recombinant α1-, α2-, α3-, and α5-containing human γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;43:970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koga H, Ishibashi H, Shimada H, Jang IS, Nakamura TY, Nabekura J. Activation of presynaptic GABAA receptors increases spontaneous glutamate release onto noradrenergic neurons of the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 2005;1046:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipska BK, Peters T, Hyde TM, Halim N, Horowitz C, Mitkus S, Weickert CS, Matsumoto M, Sawa A, Straub RE, Vakkalanka R, Herman MM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Expression of DISC1 binding partners is reduced in schizophrenia and associated with DISC1 SNPs. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:1245–1258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Low K, Crestani F, Keist R, Benke D, Brunig I, Benson JA, Fritschy JM, Rulicke T, Bluethmann H, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Molecular and neuronal substrate for the selective attenuation of anxiety. Science. 2000;290:131–134. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lüddens H, Korpi ER, Seeburg PH. GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor heterogeneity: neurophysiological implications. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00158-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lüddens H, Seeburg PH, Korpi ER. Impact of β and γ variants on ligandbinding properties of γ- aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:810–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luque JM, Malherbe P, Richards JG. Localization of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1994;24:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mäkelä R, Uusi-Oukari M, Homanics GE, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Wisden W, Korpi ER. Cerebellar γ- aminobutyric acid type A receptors: pharmacological subtypes revealed by mutant mouse lines. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:380–388. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKernan RM, Rosahl TW, Reynolds DS, Sur C, Wafford KA, Atack JR, Farrar S, Myers J, Cook G, Ferris P, Garrett L, Bristow L, Marshall G, Macaulay A, Brown N, Howell O, Moore KW, Carling RW, Street LJ, Castro JL, Ragan CI, Dawson GR, Whiting PJ. Sedative but not anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated by the GABAA receptor α1 subtype. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:587–592. doi: 10.1038/75761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohler H. GABAA receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moragues N, Ciofi P, Tramu G, Garret M. Localisation of GABAA receptor ε- subunit in cholinergic and aminergic neurones and evidence for co-distribution with the θ-subunit in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2002;111:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinkkonen ST, Hanna MC, Kirkness EF, Korpi ER. GABAA receptor ε and θ subunits display unusual structural variation between species and are enriched in the rat locus ceruleus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:3588–3595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03588.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabo ST, Blier P. Effect of the selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor reboxetine on the firing activity of noradrenaline and serotonin neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:2077–2087. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wafford KA, Ebert B. Emerging anti-insomnia drugs: tackling sleeplessness and the quality of wake time. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:530–540. doi: 10.1038/nrd2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldvogel HJ, Baer K, Eady E, Allen KL, Gilbert RT, Mohler H, Rees MI, Nicholson LF, Faull RL. Differential localization of γ-aminobutyric acid type A and glycine receptor subunits and gephyrin in the human pons, medulla oblongata and uppermost cervical segment of the spinal cord: an immunohistochemical study. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:305–328. doi: 10.1002/cne.22212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiting PJ, McAllister G, Vassilatis D, Bonnert TP, Heavens RP, Smith DW, Hewson L, O’Donnell R, Rigby MR, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Marshall G, Thompson SA, Wafford KA, Vasilatis D. Neuronally restricted RNA splicing regulates the expression of a novel GABAA receptor subunit conferring atypical functional properties. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5027–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]