Abstract

We engineered surfaces that permit the adhesion and directed growth of neuronal cell processes – axons – but that prevent the adhesion of astrocytes. This effect was achieved based on the spatial distribution of cell-repulsive poly(ethylene glycol) [PEG] nanohydrogels patterned on an otherwise cell-adhesive substrate. Patterns were identified that promoted cellular responses ranging from complete non-attachment, selective attachment, and directed growth at both cellular and subcellular length scales. At the highest patterning density where the individual nanohydrogels almost overlapped, there was no cellular adhesion. As the spacing between individual nanohydrogels was increased, patterns were identified where axons could grow on the adhesive surface between nanohydrogels while astrocytes were unable to adhere. Patterns such as lines or arrays were identified that could direct the growth of these subcellular neuronal processes. At higher nanohydrogel spacings, both neurons and astrocytes adhered and grew in a manner approaching that of unpatterned control surfaces. Patterned lines could once again direct growth at cellular length scales. Significantly, we have demonstrated that the patterning of nanoscale cell-repulsive features at microscale lengths on an otherwise cell-adhesive surface can differently control the adhesion and growth of cells and cell processes based on the difference in their characteristic sizes. This concept could potentially be applied to an implantable nerve-guidance device that would selectively enable regrowing axons to bridge a spinal-cord injury without interference from the glial scar.

1. Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) damages both ascending and descending axons at the site of a lesion, and it can result in paralysis and loss of sensation of the body below the injury. Regeneration of cut axons does not occur, primarily due to the presence of a glial scar that forms at the injury site [1]. Thus, a major issue in regenerative neuroscience is to provide an environment that permits axonal regeneration across this glial scar.

One potential solution is to engineer a bridge across the lesioned area. The advantages and challenges of various strategies to develop such a bridge have recently been reviewed [2], with the major alternatives incorporating biomaterials [3], cells [4] or a combination of both [5]. While these methods have achieved some success in promoting axonal growth, the major impediment to regeneration continues to be the presence of glial scar cells - macrophages, meningeal cells, astrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells – and the inhibitory substances they secrete. Thus, one major goal associated with constructing a bridge would be to promote axonal growth while limiting the attachment of other cell types.

The application of biomaterials to the selective growth of axons requires well-controlled surface properties [6]. The significance of biomaterial surface architecture in controlling cell-material interactions has been recognized for a long time. In contrast to situations where differential control of cell adhesion must be made solely on chemical differences, however, differentiating between cell processes and cell bodies affords the additional distinction of having significantly different characteristic sizes. Axons have a very high aspect ratio with diameters on the order of microns and lengths exceeding centimeters, and they are highly responsive to topographical features [7], substrate curvature [8] and filament diameter [9]. Cells involved with glial scarring, such as astrocytes, are physically much bigger than axons, and they have their own requirements for adhesion and growth. Thus, one approach to developing a bridge for guiding axonal regeneration would be to engineer the spatial organization of the adhesive features on a substrate at a length scale that is selectively permissive for axonal growth but repulsive to competing cells.

Patterning [10-13] offers particularly attractive ways to precisely manipulate chemical composition and topographical properties of surface microenvironments to control cell-surface interactions. Typically, such patterns involve areas that are either permissive or non-permissive to cell adhesion and/or growth. Early work by Letourneau [14], for example, demonstrated that neurons would adhere and grow on the most permissive available substrate. Many investigators have since used this method to either test neuronal preferences for various substrates or to confine neurons to specific areas of a substrate. Common methods for patterning neuronal growth have been based on UV photolithography [15, 16], microcontact printing [17], masked sputtering [18], microfluidic patterning [19], ink-jet printing [20], and fiber aligning [21], among others. Few methods, however, have thus far exploited a spatial resolution comparable to the characteristic size of a typical axon.

In this work we examine the interactions of neurons and glial cells with surfaces that contain non-adhesive poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) nanohydrogels patterned at various length scales on a silicon surface. The patterns consist of discrete, cell-repulsive, PEG nanohydrogels crosslinked using a focused electron beam. Each nanohydrogel is about 150-200 nm in diameter and is surrounded by laminin-treated silicon surface that is permissive for cell attachment and growth. Sets of nanohydrogels were arranged on surfaces in controllable patterns and at controllable distances from each other. We show that the density of adhered astrocytes strongly depends upon the nanohydrogel spacing on the otherwise adhesive surface. We also show that the spatial arrangement of the nanohydrogels can also direct axon growth and control astrocyte cell shape. Significantly, we produced a critical arrangement of PEG nanohydrogels, where the of high-aspect-ratio axons while substantially hindering the adhesion and or spreading of the larger astrocytes. Importantly, this result shows that adhesion and directed growth of axons and astrocytes can be differentially controlled based on the length scale of modulated surface cell adhesiveness.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Patterned substrate preparation

The formation of surface-bound PEG hydrogels and their patterning at sub-micron length scales on silicon wafers by electron-beam processing followed a procedure that has been described previously [22, 23]. Briefly, the wafers were first cleaned by rinsing with ethanol (Sigma Aldrich) and dried by nitrogen gas. They were then exposed to UV light for 10 min followed by exposure to low pressure oxygen plasma (~ 300 mTorr, 1.75 W) for 10 min. The wafers were immediately immersed in 2% solution of vinyl-methoxy siloxane (Gelest) in ethanol for 10 minutes, rinsed by ethanol and annealed in an oven at 110 °C for 10 min.

Hydroxy-terminated poly(ethylene glycol) [PEG; Mw = 6800 Da] was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received. Thin PEG films were spincoated (4000 rpm) from 2 wt% PEG solution in tetrahydrofuran (Sigma Aldrich) onto clean silicon wafers. In order to remove excess solvent from the films, the samples were held at ~ 100 mTorr and 45 °C for 2 hours after which they were immediately used for patterning.

Patterning was performed in a LEO 982 (Carl Zeiss) field emission scanning electron microscope (FEG-SEM). The SEM was interfaced to an external computer with custom software that could transform a user-defined 8-bit grey scale template image into a signal for controlling the position of the focused electron beam as well as its dwell time at the individual pixels. The electron energy used for patterning was 5 keV, and the current was 23 pA. One pattern used for these experiments was a 300 μm diameter circular array of points such that the spacing between points spaced 1 μm apart. After irradiation, the samples were immersed in Type I water (Millipore) at pH=5.5 for 10 minutes to remove unexposed PEG film. They were dried with dry nitrogen gas. Left behind were areas of crosslinked PEG nanohydrogel bound to the silanized silicon wafer.

2.2 Laminin adsorption onto the substrates

The samples were rinsed in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). Laminin solution was μl of laminin solution was placed onto the substrates and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. The substrates were rinsed with HBSS before seeding the cells.

2.3. Neu7 seeding onto patterned substrates

The Neu7 cell line is an astrocyte cell line immortalized by the neu oncogene [24]. Neu7 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS). The cell suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 66,000 cells/ml. The specimens were placed in 30 mm dishes, covered by 3 ml of the cell suspension, and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C.

2.4. DRG isolation and seeding onto patterned substrates

Adult mouse dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were prepared using a previously described procedure [25]. Adult mice were euthanized with CO2 and decapitated. The entire spinal column was dissected from each mouse, placed in a Petri dish containing DMEM, cleaned of attached tissue, and transferred to a fresh dish of DMEM. Two longitudinal lateral cuts were made through the ventral surface. The DRG were collected with forceps. Approximately 30 DRG were removed from each spinal cord. CNS and PNS nerve roots were removed, preserving only the ganglia, which were subsequently incubated with collagenase (0.2% in DMEM) for1 hr at 37 °C. The DRG were then transferred to a 15 ml tube with fresh DMEM to remove residual collagenase. The DRG were allowed to settle, and the supernatant DMEM was aspirated. The cells were resuspended in 2 ml modified Bottenstein-Sato N2 medium, and 1 ml of BSA solution (15% BSA in DMEM) was gently pipetted on the top of the DRG solution while preserving the phase separation between the two solutions. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 5 min at 600 The cells-containing medium onto the specimens and incubating at 37 °C. After 2 hours, 1 ml of fresh medium was added. Cultures were then incubated for an additional 22 hours at 37 °C.

2.5. Immunostaining of laminin on substrates and actin in Neu7 cells

To image distribution of adhesion-promoting laminin on the substrates after incubation, the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 minutes and reacted with monoclonal mouse anti-laminin at 4 °C for 60 minutes, followed by exposure to rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG.

Organization of the cellular cytoskeleton was analyzed by imaging their actin filaments. The cultures were permeabilized in 0.2% triton at room temperature for 5 minutes, blocked with horse serum at 4 °C for 60 minutes, and incubated with fluorescein-labelled phalloidin at room temperature for 10 minutes. After the last wash the cultures were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) and imaged.

2.6. Imaging and analysis of samples

Prior to adding cells, patterned hydrogels were imaged using a Digital Instruments NanoScope IIIa atomic force microscope (AFM) operated in contact mode in both air and water. The imaging force was minimized in order to limit deformation of the hydrated nanohydrogels by the AFM tip.

For SEM imaging, the samples containing cultured cells were removed from the incubator, washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. Then they were washed three times with PBS, fixed with 0.2% gluteraldehyde, washed with PBS, water (Millipore) and dried. For imaging, the scanning electron microscope (LEO 982) was operated at 1 keV. The same samples were also imaged using a Nikon E1000 upright fluorescence microscope.

Image processing, namely contrast adjustment and definition of the cell outlines for further analysis, was performed using Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The cell count, cell area measurement, and the definition of the major axis of Neu7 cells were determined using Image Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). The angle measurements of the major axis of Neu7 cells and fragmented DRG axons were done using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

3. Results

3.1. Patterned PEG nanohydrogels

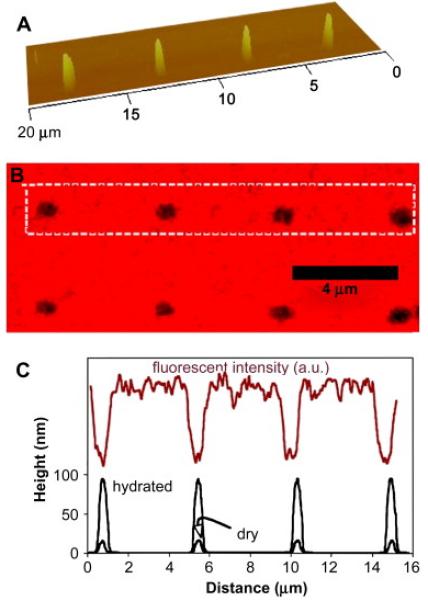

The patterned nanohydrogels were imaged by AFM (figure 1A). Topographical profiles of the features in air and water are presented in figure 1C, and these show that their swelling ratio – the ratio of the hydrated height to the dry height – was approximately five, which indicates that they are approximately 80% water when fully hydrated. The density of crosslinks in the nanohydrogels were controlled via the dwell time of the electron beam during patterning, and it was tuned to preserve the anti-fouling properties of PEG. For example, laminin adsorption was analyzed by immunofluorescence imaging (figure 1B). The minima in the profile of the fluorescent intensity correlate with the locations of the PEG nanohydrogels showing that these protein molecules adsorb on the exposed silanated silicon surface but are repelled by the nanohydrogels (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) AFM image of a row of four nanohydrogels on a silicon substrate; (B) Immunofluorescence imaging shows that laminin adsorbs onto the silanized silicon but is repelled by the patterned PEG nanohydrogels; (C) fluorescent intensity and wet/dry height profiles as a function of position along a row of four nanohydrogels.

3.2. Role of patterned hydrogels in directing the cellular growth

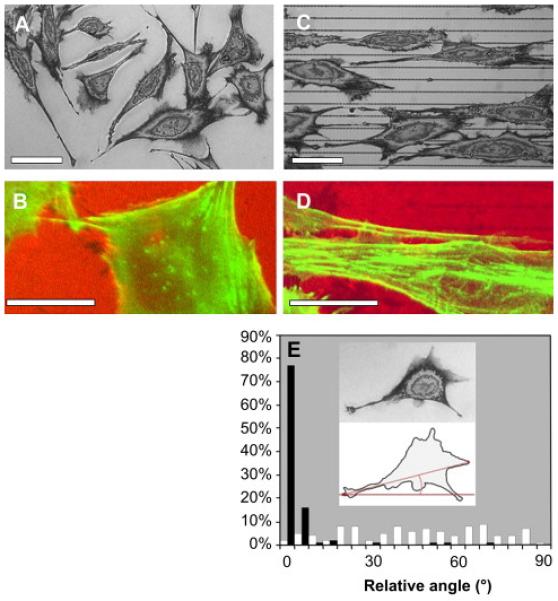

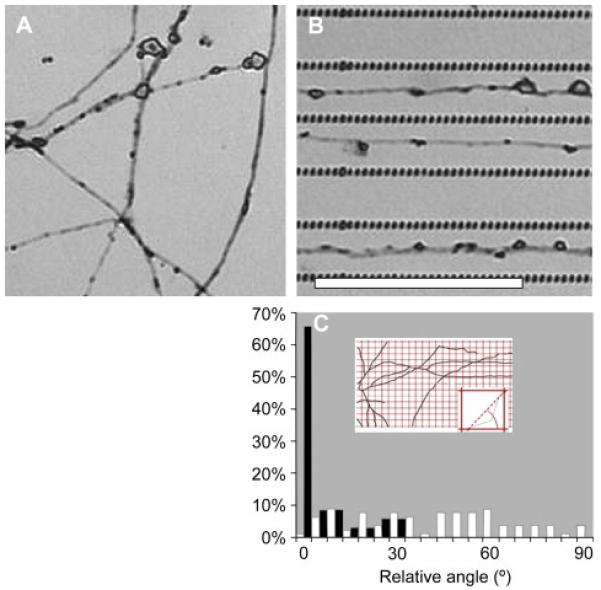

The presence of lines of PEG nanohydrogels influenced the growth of both Neu7 cells and DRG axons. Neu7 cells on the unpatterned control surface spread in random directions (figure 2A). Phalloidin staining demonstrated that cellular actin filaments were not aligned in any preferred direction (figure 2B). In contrast, on patterned surfaces, the Neu7 cells closely followed the direction of the patterned PEG lines and became highly elongated (figure 2C). The majority of Neu7 actin filaments were also aligned parallel to the nanohydrogel lines. Note that the distance between the PEG lines was smaller than the dimensions of Neu7 cell bodies, and the cells occasionally bridged over the non-adhesive PEG nanohydrogel lines. However, Neu7 filopodia were typically confined between the lines. Similarly, DRG axons extending on an unpatterned surface grew in random directions (figure 3A). In contrast, DRG axons grew predominantly in the center of the adhesive pathways defined by the patterned nanohydrogels (figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Phase contrast(A, C) and immunofluorescence (B, D) images show that Neu7 cells grow with random shape and cytoskeletal structure on unpatterned Si (A, B) but exhibit elongated shape and oriented actin filaments (C, D) on Si patterned with lines of PEG nanohydrogels (scale bars = 10 μm). The histogram (E) summarizes the angle measurement of Neu7 cells (E) on control (white bars) and patterned (black bars) surface. The inset illustrates the measured angle between the reference line and the major axis of the cell.

Figure 3.

DRG axons align themselves along the lines of PEG nanohydrogels. (A) DRG axons on unpatterned silicon grow in random directions, often forming junctions. (B) lines of PEG nanohydrogels guide axon growth (scale bar = 10 μm. (C) histogram summarizes the angle measurement of the axons on unpatterned (white) and patterned (black) silicon.

Quantitative analysis of cell and cell-process orientation confirmed that the cell-repulsive patterning aligned cells and cell processes parallel to the nanohydrogel lines. For Neu7 cells, the angle between the reference line (inset in 2E) and the major axis of each cell was measured. For DRG axons, the images were superimposed with a grid (inset in 3C), and the angle between the reference line and the line connecting the intersection points of the axons and the grid was measured. The reference line was perpendicular to the patterned PEG lines. The results are summarized in graphs in 2E and 3C. These histograms compare the direction of the cellular alignment on the control and the patterned surfaces such that 90° represents perfect alignment parallel to the lines. These histograms show that both Neu7 cells and the DRG axons displayed no preferential orientation on the unpatterned silicon, but they both exhibited a very high degree of orientation on the patterned surfaces.

3.3. Controlled adhesion of Neu7 cells to patterned substrates

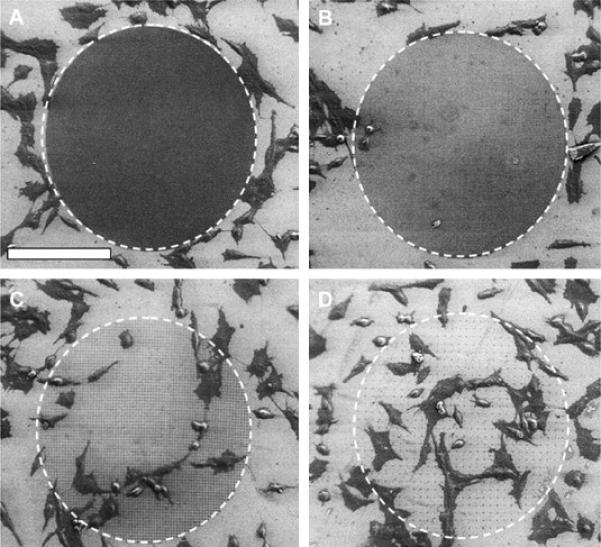

The adhesion and growth of Neu7 cells was further tested using array patterns with equal spacing between the nanohydrogels in both directions. The spacing distances, measured from g the array density of the PEG nanohydrogels concomitantly increased cell accessibility to the laminin-coated surface. Figure 4A is a low magnification scanning electron micrograph showing a circular pattern of nanohydrogels spaced 1 μm apart. Neu7 cells are clearly visible surrounding the array. However, no cells adhered to the patterned PEG in this particular experiment, and very few adherent cells were observed in any of our experiments involving nanohydrogel arrays with a 1 μm spacing. Furthermore, cells attached to the surface surrounding the pattern did not grow (figure 4B), a very small number of cells adhered to the pattern and these spread very little. Cells that adhered to the surrounding substrate did not significantly grow into the pattern. AFM, SEM, the underlying adhesive laminin-coated substrate, but this surface was nevertheless repulsive to the Neu7 cells. The cell-interactive character depended strongly on the area fraction of exposed laminin surface, and, as the nanohydrogel spacing increased (figure 4C), the overall surface became more amenable to Neu7 cell attachment and spreading. When the nanohydrogel spacing was increased to 10 μm, the Neu7 morphology could not be distinguished from the unpatterned control surface (figure 4D).

Figure 4.

The density of adhered Neu7 cells depends on the density of nanohydrogels. A circular area with PEG nanohydrogels spaced 1 μm apart (A) completely inhibits the Neu7 adhesion and ingrowth from the surrounding unpatterned surface. Discrete PEG hydrogels (B) spaced by 2 μm expose adhesive substrate, but Neu7 adhesion and ingrowth remain low. The cells adhere to the pattern when the spacing increases to 4 μm (C). Cell adhesion and spreading is comparable to the neighboring unpatterned region when spacing between the hydrogels is 10 μm (D). (scale bar = 100 μm)

Cell-count and surface-area measurements revealed that the number of Neu7 cells and their size both depended on the nanohydrogel spacing. Figure 5 presents the quantitative analysis of the area of the cells that spread over the patterned arrays. The inset demonstrates the highlighted area of the cells. In the case of cells that adhered at the border between patterned and control surface, only the portion over the patterned areas was included in the analysis. Clearly, patterns with a spacing of 1 and 2 represent surfaces that contain adhesive regions identical to the control, but their area fraction and spatial distribution is such that the cells did not adhere. In contrast, cell behavior on surfaces with nano-patterned surface. Furthermore, we found that the size of individual Neu7 cells was also a function of the surface density of PEG nanohydrogels, with the area per cell decreasing on the more closely spaced surfaces (figure 5B). Remarkably, the contact area of the cells on the control surface was more land on the 1 μm and 2 μm space d patterns, they did not develop any processes that would indicate the ability to develop additional points of contact and spreading.

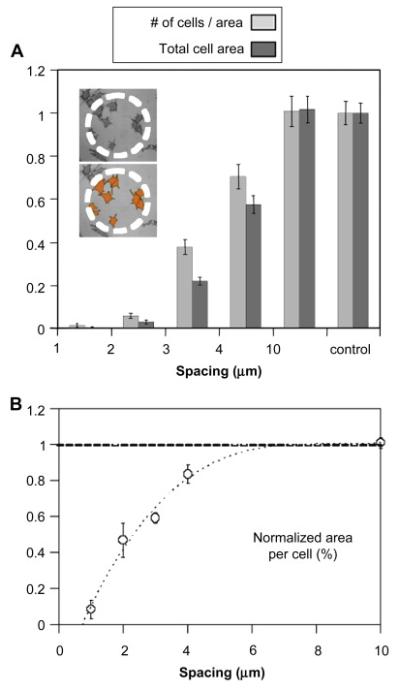

Figure 5.

The number of adhered Neu7 cells and their size depend on the inter-nanohydrogel spacing. The results are normalized to the control. The inset in (A) illustrates the image processing used for analysis. The contact area between the cells and the substrate increases with the decreasing density of PEG microhydrogels (A). The average size of the cells is also a function of the spacing between the nanohydrogels (B).

3.3. Selective growth of DRG axons

While all patterns contained regions of laminin-coated substrate, only the surface with an area ratio of adhesive to nonadhesive regions larger than a critical value permitted the axons to adhere. Thus, while Neu7 cells did not adhere to patterns of nanohydrogels at 1 and 2 μm spacing, DRG axons freely grew and branched on the laminin-spaced hydrogels (figure 6). They grew equally as well on arrays with the nanohydrogel spacings of 3 , 4, and 10 μm.

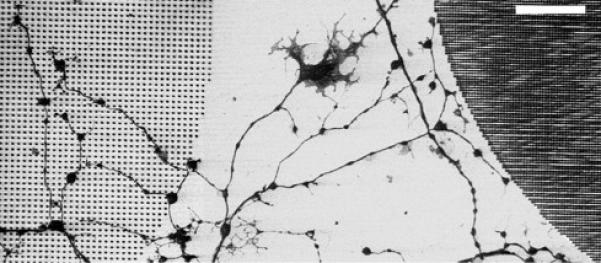

Figure 6.

DRG axons grow from unpatterned control silicon surface into arrayed PEG nanohydrogels spaced by 2 μm (left), but they can not penetrate into the more dense array (right) consisting of nanohydrogels spaced by 1 μm. (scale bar = 20 μm).

4. Discussion

Any effort to promote axonal growth through a lesion in the central nervous system must contend with the inhibitory properties of the glial scar. Our results suggest that one potential way to bridge the scar is to use synthetic materials that selectively permit the attachment and growth of axons, while inhibiting the adherence of larger cells. Here we study the competing effects of astrocytes with neuronal axons. One can envision qualitatively similar behavior by other cell types involved in inhibitory scarring. Despite the fact that astrocytes have been shown to enhance neurite growth in several studies [13, 26-28], these cells are recognized as being highly plastic in nature and the fact that they can provide inhibitory cues is well recognized [5, 29-31]. We show that a closely spaced array of non-adhesive PEG nanohydrogels can confine and promote directional axonal growth while simultaneously limiting the invasion of cells whose characteristic size is about an order of magnitude larger than the lateral dimension of an axon. As the spacing between nanohydrogels gets larger, other cells do attach, yet the shape of the nanohydrogel arrays still defines cellular polarity. Thus, varying the relative locations of the cell-repulsive nanohydrogels is by itself sufficient to significantly influence cellular behavior.

Directional axonal growth has previously been achieved by creating patterns of adhesive and non-adhesive regions on flat substrates. While several different methods, including microcontact printing [17], inkjet printing [20], and UV lithography [32] have been used to accomplish this, none of these methods have achieved spatial resolution comparable to the lateral dimensions of individual axons. Because these patterning methods were used to produce stripes other cell types. Electron-beam patterning, on the other hand, can form adhesive areas with dimensions much smaller than both glial cells and the lateral width of individual axons.

PEG is well known for its anti-fouling ability [33], and PEG-modified surfaces have long been known for being non-permissive to protein adsorption [34], bacterial adhesion [35, 36], and eukaryotic cell adhesion [37]. In aqueous media, a loosely crosslinked PEG hydrogel is highly flexible and extends into the solution. As molecules approach the hydrogel from the surrounding medium, they initiate the compression of PEG molecules inducing a steric repulsion effect [38]. The density of crosslinks in the nanohydrogels used in the present work was chosen to maximize this effect while maintaining the nanohydrogel stability during cell culture. Our results confirmed that these repulsive properties of PEG hydrogels could be utilized to direct or reduce the adhesion of cells.

We speculate that the cell repulsiveness of the patterned surfaces is due primarily to the anti-fouling properties of PEG rather than to the topographic effects from their hydrated height (~100 nm, figure 1). Rajnicek et al. [7] demonstrated that optimal topographically-directed axon growth was obtained by features that were 1.1 patterns controlled the growth direction less precisely. A great degree of control was also [39]. Another study showed that the alignment of DRG neurites was significantly induced by substrates with roughness of at least 250 nm on polystyrene modified by contact molding [40, 41]. Our AFM measurements of hydrated nanohydrogels showed that they are smaller than the minimal dimensions previously identified, yet in our experiments they clearly influence the cellular response suggesting that the effects are largely biochemical rather than topographical.

Much is already known about how microscale surface patterns affect cell adhesion and oriented growth. Consistent with this, in our work, when hydrogels were patterned into lines direction, cell growth and spreading was confined to the wider adhesive regions. Morphologically, the cells elongated in the direction parallel to the closely spaced hydrogels. Alignment of glial cells has previously been achieved by microlithography of continuous stripes of either polylysine [42] or laminin [27, 43, 44] or by fabricating topographical features [45]. Our experiments demonstrate the additional point that directed cell elongation can be achieved by an arrangement of discrete adhesive and non-adhesive regions without forming perfectly continuous guiding tracks.

The ability to make nanoscale cell-repulsive features over a range of microscale distances enabled us to demonstrate the modulation of Neu7 cell adhesion as a function of the nanohydrogel separation. Roughly speaking, the density of the Neu7 cells present on the patterned surfaces is inversely proportional to the surface density of the PEG nanohydrogels. Significantly, the cells are able to bind to the adhesive portion of the surface despite the presence of the non-adhesive nanohydrogels over which the cells have to bridge. The average total contact area of the cells to the surface increases with the increasing spacing between the PEG nanohydrogels. The cells respond more favorably to surfaces that contain a smaller density of nonadhesive nanohydrogels. However, when the availability of the adhesive surface is limited, because of patterns with closely spaced nanohydrogels, Neu7 cells do not adhere.

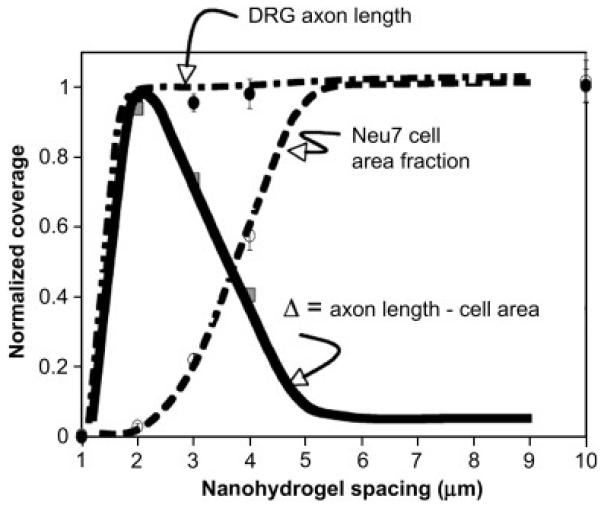

Importantly, some of the same patterns that resist Neu7 cell adhesion promote the adhesion and growth of DRG axons (figure 7). Specifically, axons can grow freely through the other hand, hardly adhere to such a surface (figure 4B). Instead, we find that the Neu7 cells need intergel spacings of 3 μm before significantly adhering, and they need an intergel spacing exceeding 4 μm, possibly being as high as 10 μm, before behaving like similar cells grown on an unpatterned control surface (figure 5).

Figure 7.

Arrayed nanohydrogels with microscale spacings differentially enable axon growth. The dashed line represents the area fraction of an array covered by Neu7 cells. The dot-dashed line represents the average axon length. Both are normalized to the analogous values from the unpatterned control surface. The solid line, Δ, represents the difference between these. Its maximum close to unity at d=2 μm indicates that the surface is permissive to axonal growth but resistant to Neu7 adhesion.

We speculate that the Neu7 cells can adhere to surfaces with larger intergel spacings because eukaryotic cell adhesion onto surfaces – both natural and synthetic - is typically mediated by focal contacts [46-48]. These contacts involve clusters of receptor ligands (e.g. integrins) on cell surfaces that can bind a variety of extracellular matrix adhesion-promoting proteins (e.g. laminin, fibronectin, vitronectin, collegen). Much is known about such contacts when they have grown into full focal adhesions whose dimensions can be on the order of a micron. In the present context, focal contacts/adhesions can form on patches of adhesive substrate surface with subcellular dimensions, on the order of a few microns in size. The local flexibility of the cell wall would enable the cell to nonadhesively bridge the nanosized cell-repulsive features defining the microsized adhesive patches.

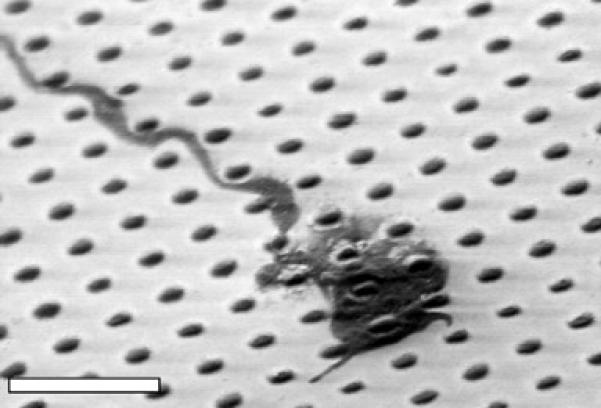

Axonal growth cones have lateral dimensions of several microns or more, and, like the astrocytes, these growth cones must interact directly with the cell-repulsive nanohydrogels. Figure 8, for example, shows one such DRG growth cone that straddles several cell-repulsive nanohydrogels. Presumably, the surface presents sufficient cell-adhesive surface that the growth cone remains not only bound to it but also in a mode of active growth. The axon trailing a growth cone has submicron dimensions, and figure 8 also shows such an axon faithfully follows cell-adhesive surface in between cell-repulsive nanohydrogels.

Figure 8.

SEM image of a DRG axon and its growth cone traversing a cell-adhesive surface patterned with cell-repulsive PEG nanohydrogels spaced 2 μm apart. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Spatially modulated cell adhesiveness is a new means by which to achieve differential cell adhesion. In the context of axonal regeneration, one envision fabricating an implantable device that would selectively guide growing axons while impeding the adhesion of competing cells from an inhibitory glial scar. Two-dimensional patterns on a thin biocompatible material could be created and that material then rolled into multi-walled tube similar to a device presented by Li et al. [49]. The pattern design would both promote unidirectional growth of axons while selectively blocking inhibiting glia from adhering and forming scar tissue. In addition, nanohydrogels patterned from PEG containing functional groups such as amine endgroups [50, 51] could be decorated with relevant oligopeptides and other biological molecules that can control specific interactions and provide for additional biochemical control over the axonal regrowth.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that the arrangement of nanoscale cell-repulsive features patterned on an otherwise cell-adhesive surface provides a mechanism for differentially controlling cell adhesion. Specifically, by controlling the microscale spatial distribution of nanoscale features, small cell processes can be permitted to adhere and grow on a surface while larger cells are repelled by that same surface. Here we have demonstrated this effect by discriminating between axons with lateral dimensions on the order of 1 μm and immortalized astrocytes whose characteristic size is on the order of 10-20 μm. In this case, a separation of about 2 μm between nanosized cell-repulsive PEG nanohydrogels is sufficient to both allow and guide axon growth while simultaneously inhibiting astrocyte adhesion and growth. One can envision that the idea of length-scale mediated differential cell adhesion can be extended to other combinations of cells and cell processes – e.g. differentiating between bacteria and eukaryotic cells – where there are significant difference in the cell size and binding mechanisms.

Acknowledgment

This research project has been supported in part by the Army Research Office (ARO grants #DAAD19-03-1-0271 and W911NF-07-1-0543).

References

- 1.Ellis-Behnke R. Nano neurology and the four P’s of central nervous system regeneration: Preserve, permit, promote, plasticity. Medical Clinics of North America. 2007;91(5):937–962. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller HM, Fawcett JW. Building a bridge: engineering spinal cord repair. Exp Neurol. 2002;174(2):125–136. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt CE, Leach JB. Neural tissue engineering: Strategies for repair and regeneration. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;5:293–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunge MB, Pearse DD. Transplantation strategies to promote repair of the injured spinal cord. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2003;40(4 suppl. 1):55–62. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.08.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawcett JW, Asher RA. The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49(6):377–391. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu L, Leipzig ND, Schoichet MS. Promoting neuron adhesion and growth. Mterials Today. 2008 May;11:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajnicek A, McCaig C. Guidance of CNS growth cones by substratum grooves and ridges: effects of inhibitors of the cytoskeleton, calcium channels and signal transduction pathways. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2915–2924. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.23.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smeal RM, Rabbitt R, Biran R, Tresco PA. Substrate curvature influences the direction of nerve outgrowth. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;33(3):376–382. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-1740-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen X, Tresco PA. Effect of filament diameter and extracellular matrix molecule precoating on neurite outgrowth and schwann cell behavior on multifilament entubulation bridging device in vitro. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A. 2006;76(3):626–637. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christman KL, Enriquez-Rios VD, Maynard HD. Nanopatterning Proteins and Peptides. Soft Matter. 2006;2:928–939. doi: 10.1039/b611000b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalby MJ, Childs S, Riehle MO, H.J.H. J, Affrossman S, Curtis ASG. Fibroblast reaction to island topography: changes in cytoskeleton and morphology with time. Biomaterials. 2003;24:927–935. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lussi JW, Tang C, Kuenzi P-A, Staufer U, Csucs G, Voros J, et al. Selective molecular assembly patterning at the nanoscale: a novel platform for producing protein patterns by electron-beam lithography on SiO2/indium tin oxide-coated glass substrates. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:1781–1786. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorenson A, Alekseeva T, Katechia K, Robertson M, Riehle MO, Barnett SC. Long-term neurite orientation on astrocyte monolayers aligned by microtopography. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5498–5508. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letourneau PC. Cell to substratum adhesion and guidance of axonal elongation. Developmental Biology. 1975;44(1):92–101. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fromherz P, Schaden H. Defined neuronal arborizations by guided outgrowth of leech neurons in culture. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;6(9):1500–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorribas H, Padeste C, Tiefenauer L. Photolithographic generation of protein micropatterns for neuron culture applications. Biomaterials. 2002;23(3):893–900. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kam L, Shain W, Turner JN, Bizios R. Axonal outgrowth of hippocampal neurons on micro-scale networks of polylysine-conjugated laminin. Biomaterials. 2001;22(10):1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saneinejad S, Shoichet MS. Patterned poly(chlorotrifluoroethylene) guides primary nerve cell adhesion and neurite outgrowth. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;50(4):465–474. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000615)50:4<465::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinoia S, Bove M, Tedesco M, Margesin B, Grattarola M. A simple microfluidic system for patterning populations of neurons on silicon micromachined substrates. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1999;87(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanjana NE, Fuller SB. A fast flexible ink-jet printing method for patterning dissociated neurons in culture. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;136(2):151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YT, Haftel VK, Kumar S, Bellamkonda RV. The role of aligned polymer fiber-based constructs in the bridging of long peripheral nerve gaps. Biomaterials. 2008;29(21):3117–3127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krsko P, Saaem I, Clancy R, Geller H, Soteropoulos P, Libera M. E-beam patterned hydrogels to control nanoscale surface bioactivity. In: Lai WY, Ocola LE, Pau S, editors. Nanofabrication: Technologies, Devices, and Applications II. SPIE; Bellingham: 2005. p. 600201. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krsko P, Sukhishvili S, Mansfield M, Clancy R, Libera M. Electron-beam surface-patterned poly(ethylene glycol) microhydrogels. Langmuir. 2003;19(14):5618–5625. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith-Thomas L, Fok-Seang J, Stevens J, Du J-S, Muir E, Faissner A, et al. An inhibitor of neurite outgrowth produced by astrocytes. Journal of Cell Science. 1994;107:1–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott BS. Adult mouse dorsal root ganglia neurons in cell culture. Journal of Neurobiology. 1977;8(5):417–427. doi: 10.1002/neu.480080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies SJA, Fitch MT, Memberg SP, Hall AK, Raisman G, Silver J. Regeneration of adult axons in white matter tracts of the central nervous system. Nature. 1997;390(6661):680–683. doi: 10.1038/37776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Recknor JB, Recknor JC, Sakaguchi DS, Mallapragada SK. Oriented astroglial cell growth on micropatterned polystyrene substrates. Biomaterials. 2004;25(14):2753–2767. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller RH. Building bridges with astrocytes for spinal cord repair. Journal of Biology. 2006;5(6) doi: 10.1186/jbiol40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fawcett J. Overcoming inhibition in the damaged spinal cord. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2006;23(3-4):371–383. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gris P, Tighe A, Levin D, Sharma R, Brown A. Transcriptional regulation of scar gene expression in primary astrocytes. Glia. 2007;55(11):1145–1155. doi: 10.1002/glia.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horner PJ, Gage FH. Regenerating the damaged central nervous system. Nature. 2000 October 26;407:963–970. doi: 10.1038/35039559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark P, Britland S, Connolly P. Growth cone guidance and neuron morphology on micropatterned laminin surfaces. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:203–212. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krsko P, Libera M. Bio-interactive Hydrogels. Materials Today. 2005;8(12):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang M, Desai T, Ferrari M. Proteins and cells on PEG immobilized silicon surfaces. Biomaterials. 1998;19:953–960. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai NP, Hossainy SFA, Hubbell JA. Surface-immobilized polyethylene oxide for bacterial repellence. Biomaterials. 1992;13:417–420. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(92)90160-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krsko P, Kaplan J, Libera M. Spatially controlled bacterial adhesion using surface-patterned poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.08.025. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drumheller PD, Hubbell JA. Densely crosslinked polymer networks of poly(ethylene glycol) in trimethylolpropane triacrylate for cell-adhesion-resistant surfaces. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1995;29(2):207–215. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morra M. On the molecular basis of fouling resistance. Journal of Biomaterials Science Polymer Edition. 2000;11:547–569. doi: 10.1163/156856200743869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowell-Mesfin NM, Abdul-Karim MA, Turner AM, Schanz S, Craighead HG, Roysam B, et al. Topographically modified surfaces affect orientation and growth of hippocampal neurons. J Neural Eng. 2004;1(2):78–90. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/1/2/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomez N, Lu Y, Chen S, Schmidt CE. Immobilized nerve growth factor and microtopography have distinct effects on polarization versus axon elongation in hippocampal cells in culture. Biomaterials. 2007;28(2):271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh JF, Manwaring ME, Tresco PA. Directional neurite outgrowth is enhanced by engineered meningeal cell-coated substrates. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(7-8):1085–1094. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang JC, Brewer GJ, Wheeler BC. A modified microstamping technique enhances polylysine transfer and neuronal cell patterning. Biomaterials. 2003;24(17):2863–2870. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmalenberg KE, Uhrich KE. Micropatterned polymer substrates control alignment of proliferating schwann cells to direct neuronal regeneration. Biomaterials. 2005;26(12):1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson DM, Buettner HM. Schwann cell response to micropatterned laminin surfaces. Tissue Engineering. 2001;7(3):247–265. doi: 10.1089/10763270152044125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biran R, Noble MD, Tresco PA. Directed nerve outgrowth is enhanced by engineered glial substrates. Exp Neurol. 2003;184(1):151–152. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00253-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavalcanti-Adam E, Micoulet A, Blummel J, Auernheimer J, Kessler H, Spatz JP. Lateral spacing of integrin ligands influences cell spreading and focal adhesion assembly. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;85:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavalcanti-Adam E, Volberg T, Micoulet A, Kessler H, Geiger B, Spatz JP. Cell spreading and focal adhesion dynamics are regulated by spacin g of integrin ligands. Biophysical Journal. 2007 April;92:2964–2974. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sastry SK, Burridge K. Focal adhesions: A nexus for intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;261:25–36. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Shi R. Fabrication of patterned multi-walled poly-l-lactic acid conduits for nerve regeneration. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;165(2):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong Y, Krsko P, Libera M. Protein surface patterning using nanoscale PEG hydrogels. Langmuir. 2004;20(25):11123–11126. doi: 10.1021/la048651m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saaem I, Papasotiropoulos V, Wang T, Soteropoulos P, Libera M. Hydrogel-based protein nanoarrays. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2007;7(8):2623–2632. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]