Abstract

Research into anxiety has largely ignored the dynamics of family systems in anxiety development. Coparenting refers to the quality of coordination between individuals responsible for the upbringing of children and links different subsystems within the family, such as the child, the marital relationship, and the parents. This review discusses the potential mechanisms and empirical findings regarding the bidirectional relations of parent and child anxiety with coparenting. The majority of studies point to bidirectional associations between greater coparenting difficulties and higher levels of anxiety. For example, the few available studies suggest that paternal and perhaps maternal anxiety is linked to lower coparental support. Also, research supports the existence of inverse links between coparenting quality and child anxiety. A child’s reactive temperament appears to have adverse effects on particularly coparenting of fathers. A conceptual model is proposed that integrates the role of parental and child anxiety, parenting, and coparenting, to guide future research and the development of clinical interventions. Future research should distinguish between fathers’ and mothers’ coparenting behaviors, include parental anxiety, and investigate the coparental relationship longitudinally. Clinicians should be aware of the reciprocal relations between child anxiety and coparenting quality, and families presenting for treatment who report child (or parent) anxiety should be assessed for difficulties in coparenting. Clinical approaches to bolster coparenting quality are called for.

Keywords: Coparenting, Child anxiety, Parental anxiety, Support, Undermining

Introduction

It has been clear for some time that individual psychopathology and family relationships are intertwined. Depression, for example, is reciprocally related to couple conflict; maternal depression is associated with maladaptive parent–child relations; and parent–child conflict is associated with child depression (Restifo and Bogels 2009; see also the review of Heinrichs et al. 2010, on couple functioning and child behavior problems). Far less research, however, has been conducted on the relations between anxiety and family relationships. The purpose of this article is to propose hypotheses and examine what is known about the relations between family members’ anxiety and coparenting relations. We focus on coparenting because of its central role in the nuclear family, representing the intersection of the couple relationship and parent–child relations.

Research into family influences on child anxiety has mainly focused on individual parental factors—parental anxiety and parenting behaviors. Evidence suggests that both parental anxiety and anxiety-enhancing parenting behaviors (such as overcontrol and anxious modeling) can aversely affect the course of vulnerable child characteristics (Bögels and Brechman-Toussaint 2006; Murray et al. 2009; Rubin et al. 2009). Although such research considers transactional pathways and mediating/moderating factors, the “dyadic” emphasis of most research on parents’, and in particular mothers’, individual influences on child anxiety ignores the potential importance of the family system as an organized whole in anxiety development.

In considering the bidirectional influence of family systems and anxiety, the coparenting relationship may serve a useful organizing function. Coparenting refers to the quality of coordination between individuals responsible for the care and upbringing of children (McHale et al. 2004b). The coparenting construct is useful as it links different subsystems within the family, such as the child, the marital relationship, the mother’s parenting role, and the father’s parenting role. Coparenting consists of several key dimensions, which may play separate and/or related roles in elucidating the relations between anxiety and family interaction. One of the major coparenting dimensions that have been distinguished and investigated includes the coparents’ solidarity (McHale et al. 2004b) or support versus undermining of each other’s coparental role (Feinberg 2003). Other coparenting dimensions concern agreement or disagreement on childrearing issues, the joint management of family interactions (e.g., interparental conflict, coalitions, and interactional balance in family communication), and the division of child-related labor (Feinberg 2003).

Recent theories on the development of anxiety present a multifactor model in which anxiety can result from a complex interaction between parental anxiety, child biological vulnerability (genetic and temperamental), cognitive aspects (attention, information processing), parenting behaviors and anxiogenic modeling, adverse life events, and socio-cultural influences (Brook and Schmidt 2008; Murray et al. 2009; Rubin et al. 2009). Child temperamental predispositions that are theorized and have been found to predict later anxiety include behavioral inhibition in early childhood (Fox et al. 2005; Rubin et al. 2009; Biederman et al. 2001), that is, the tendency to respond withdrawn to new situations and people (Kagan and Snidman 1991). Behavioral inhibition is in turn predicted by negative reactivity in early infancy, that is, excessive reactivity to novel stimuli (Kagan and Snidman 1991). Many (parent-report) studies use the somewhat broader conceptualization of a reactive or difficult child temperament, including negative emotionality, irritability, and fussiness, as a temperamental predisposition for anxiety. Meta-analytic studies have shown that parental overcontrol, and, to a lesser extent, parental negativity are associated with child anxiety, with effect sizes of .25 (McLeod et al. 2007) to .58 (from observational studies; Bruggen et al. 2008) for overcontrol, and .20 for negativity (McLeod et al. 2007). Parental negativity or rejection is thought to foster anxiety by promoting the child’s perceptions of the self as less worth or competent and of the environment as hostile or threatening, whereas overcontrol or overprotection may give rise to anxiety by impeding the development of the child’s autonomy, and restraining opportunities for developing necessary coping skills, leading to reduced self-efficacy.

In Feinberg’s (2003, p. 111) ecological model about the structure and context of coparenting, coparenting is considered a mediator and moderator linking contextual factors, and parent and child characteristics and outcomes, and, as such, is “the centre about which family process evolves” (Weissman and Cohen 1985, p. 24). Extending this model to consider anxiety in particular leads to several initial hypotheses. For example, parents’ individual characteristics such as trait anxiety may affect coparenting, for instance by impeding their propensity to express emotional support. In turn, coparenting conflict may undermine parental adjustment, for instance leading to chronic stress which could serve to potentiate tendencies toward a range of anxiety disorders. Coparenting relations may affect child anxiety either directly (e.g., child-related disagreements may induce anxiety in the child by creating an insecure environment) or via parenting behavior (e.g., if one parent does not feel supported by the other parent he or she may become more negative toward the child, or perhaps compensate by forming a symbiotic relationship with the child). Child characteristics may also affect coparenting; for example, raising a temperamentally difficult child may cause augmented stress and conflict in the coparenting relationship. An additional dimension of coparental coordination relates to the coherence of differences between parents’ childrearing approaches. Recent theories have drawn attention toward possible differences between fathers’ and mothers’ roles (Paquette 2004) and their differential effect on child anxiety (Bögels and Phares 2008; Bögels et al. 2011; Bögels and Perotti 2011). Of note, although a child’s coparents are not necessarily (restricted to) his or her biological mother and father, most research on coparenting has concentrated on traditional two-parent families with a father and a mother.

In this review, the role of coparenting in anxiety is discussed from several angles. Given the lack of research on coparenting specifically addressing anxiety, we will consider anxiety broadly, including anxiety symptoms, disorders, and child temperamental predispositions of anxiety (i.e., behavioral inhibition and negative reactivity); where empirical work on anxiety per se is quite scarce, we consider existing work on internalizing problems. Internalizing problems include not only anxiety, fear, and shyness, but also depression, sadness, low self-esteem, and somatic symptoms (Achenbach and Edelbrock 1981).

The complex relations between coparenting and anxiety involve at least two bidirectional effects: that from parental anxiety to coparenting and vice versa and that from child anxiety to coparenting and vice versa. Each of these relations will be discussed in turn. We will first focus on parental anxiety and its relation to coparenting. Second, we discuss the ways in which child anxiety (or its predictor, reactive temperament) affects coparenting Third, the impact of coparenting on child anxiety, the relation most often addressed in current research, is discussed. In each of these sections, we first describe potential models and mechanisms explaining the relation in question and then address empirical research on it. In the absence of longitudinal studies, cross-sectional research is sometimes cited to illustrate potential directional effects from coparenting to anxiety or vice versa, although its value for making causal inferences is obviously limited. In the final concluding section, we summarize and discuss the findings on the mutual relations between coparenting and anxiety, paying special attention to the potentially different roles of fathers and mothers in these relations. We then present a model integrating family functioning and parental and child anxiety and discuss mediators and moderators of the links herein. Finally, we discuss future research and outline the implications of available research for clinical work with children and families.

Parental Anxiety and Coparenting

The relations between parental anxiety and coparenting are addressed by only a handful of studies. Below, the results of empirical studies on these relations are presented. In view of the lack of research directly addressing these links, the findings are supplemented with evidence on the relation between adult anxiety and marital functioning, and between parental anxiety and parenting. First, models and mechanisms that may explain the links between parental anxiety and coparenting are discussed.

Models and Mechanisms

Parental psychopathology can be assumed to have an effect on parents’ ability to display supportive and non-dismissive coparenting. For instance, an anxious parent may be less tolerant of his/her partner’s different approaches to parenting, and as a result, may have more disagreements on child rearing with the coparent than a non-anxious parent. In considering how parental anxiety may theoretically be related to coparenting, it is helpful to distinguish between the influence of the anxious and non-anxious partner on the coparenting relationship. An anxious parent can be expected to be concerned about the partner’s encouragement of child autonomy, since he/she is likely to perceive this type of parenting as lax or risky. Given a high level of anxiety, such a parent may even undermine the parenting of the non-anxious partner instead of calmly discuss such differences in parenting approaches. The differences in parental strivings between an anxious parent and his or her coparent may thus give rise to increased disagreements on child rearing (Feinberg 2003). If the anxious parent’s strategy is to avoid the anxiety-provoking stimulus, s/he may withdraw from coparenting and parenting interactions. Such withdrawal may lead to an imbalance in father–mother–child interactions, which in turn may contribute to the formation of coalitions and/or triangulation (the latter term referring to engaging a child in interparental conflict). Withdrawal by an anxious parent may also lead to covert, rather than overt, forms of coparental conflict. In addition, the potential difference in childrearing attitudes between the anxious parent and the coparent may affect the similarity of their parenting roles—for example, more stereotypic (and thus dissimilar) roles if the mother is the anxious partner. This more pronounced inequality in the division of child-related labor may then lead to dissatisfaction and conflict in this area of coparenting.

A non-anxious partner’s influence on coparenting with an anxious parent can be positive or negative. The partner may reduce the anxious parent’s worries by an appropriately supportive approach toward the anxious parent, or by sensitively highlighting the capabilities of the child (e.g., “s/he knows how to cross the street safely”). If the partner, on the other hand, is dismissive about the parent’s anxiety and worries in the presence of the child, the anxious parent may feel undermined in her parenting role. The attitude of the non-anxious partner on the coparental relationship may have similar positive or negative consequences for the other coparenting dimensions, such as the way disagreements are handled, conflicts are managed, and triadic family interactions are shaped.

The way anxiety in a parent shape the coparental relationship may chiefly depend on coparental support. Supportive coparents collaborate to divide child-raising tasks based on their individual qualities. For example, the anxious parent may be more effective in providing care whereas the non-anxious parent may be more effective in stimulating exploration. Thus, the anxious parent may leave certain tasks to the non-anxious parent, such as modeling and encouraging courageous behaviors in domains in which the anxious parent cannot easily perform those tasks. The non-anxious parent, on the other hand, may leave tasks such as comforting or protecting the child to the anxious parent. Coparents that support each other in these differentiations of roles based on anxiety-related qualities are expected to have a healthier coparenting relationship. Unsupportive coparents may have difficulty trusting the other parent to take over tasks or will not take over tasks from the other parent in a sensitive way. Thus, it could be hypothesized that in a supportive coparenting relationship, a parent without anxiety disorder may more effectively compensate for the other parent’s anxiety disorder.

Another but related way to think about the relationship between parental anxiety and coparenting concerns the effect of parental stress on coparenting. Parents with anxiety disorder are likely to be more stress prone. Heightened stress on the individual parent is assumed to undermine that parent’s ability to maintain coordination and harmony in the coparenting relationship (Feinberg 2003). In addition, as stress and dysfunction in one individual is a relatively seamless product and cause of stress in a larger system, such as the parental subsystem (Davies et al. 2004), the coparent without anxiety disorder may similarly become stressed, which will in turn negatively affect his or her capacity to display positive coparenting.

Regarding the other direction of effect, that from coparenting to parental anxiety, it has been suggested to consider coparenting from a developmental point of view (McHale et al. 2004b). When parents learn to cooperate and collaborate in the shared raising of a child, felt stress and perceived efficacy may similarly be affected by the coparental dynamic (Grych and Clark 1999; Feinberg 2003). McHale et al. (2004b) suggest that also more lasting personality traits of parents may likewise transform, for good or ill, as a function of the degree of support, solidarity, and validation experienced within the coparental alliance. Therefore, parental anxiety may increase of decrease depending on how the coparental relationship evolves.

Empirical Findings

As only few studies have directly investigated the association between parental anxiety and coparenting, we will, first, briefly review the literature on how adult anxiety affects marital functioning; second, how parental anxiety affects parenting behavior; and, third, turn to the relation between parental anxiety and coparenting. Although the marital relationship is generally considered distinct from the coparenting relationship, their mutual association is well established (e.g., Cook et al. 2009).

First, considering the relation between adult anxiety and marital functioning, there is evidence that people seeking treatment for anxiety disorders as well as people with anxiety disorders in community samples report lower marital satisfaction (see Whisman et al. 2004, for an overview). A meta-analysis on the relation between marital satisfaction and personal wellbeing, in which wellbeing was assessed using depression and anxiety symptoms scales, reported an average weighted effect size r of .37 for cross-sectional and .25 for longitudinal prospective designs (Proulx et al. 2007). Taken together, there is ample evidence that marital quality and marital satisfaction are associated with adult anxiety disorder.

Across three studies, there is evidence that the presence of an anxiety disorder is not only associated with lower marital quality in the person having the disorder, but also in the partner. However, the findings are not consistent across these studies. Whisman et al. (2004), investigating 774 married couples, found that self-reported marital satisfaction was predicted by an individual’s but not partner’s level of anxiety. Although one other study found similar results regarding social anxiety (Filsinger and Wilson 1983), a third study found a greater influence of spouse than own phobia/panic disorder on self-reported marital quality (McLeod 1994). In addition to self-reported marital satisfaction and quality, anxiety disorders are also associated with more divorce. For example, a large epidemiological study (N = 5,877) found divorce rates to be elevated in people with anxiety disorders, with an odds ratio of 1.8 for first marriages for any anxiety disorder (Kessler et al. 1998).

Second, besides marital functioning, another construct worth exploring when considering the relation between parental anxiety and coparenting is parenting behavior. Considering the relationship between parental anxiety and parenting, research has focused on how parental anxiety is associated with more overcontrolling parenting of the child (see the reviews of Bögels and Brechman-Toussaint 2006; Kaitz and Maytal 2005; Murray et al. 2009). However, meta-analytic data have shown little evidence so far to support the assumed relation between parental anxiety and overcontrol of their child (d = .08; Bruggen et al. 2008).

No meta-analytic research on the relationship between parental anxiety and child criticism or rejection exists, but study findings are mixed. For example, partial support was reported by Bögels et al. (2008), who found fathers, but not mothers, with anxiety disorders to be more rejective toward their children in observed parent–child discussions. Other studies found no support, for instance Moore et al. (2004), found no significant effect of mothers’ anxiety diagnosis or of the interaction of mother and child anxiety disorder on observed maternal warmth, and Turner et al. (2003) found that parents (predominantly mothers) with anxiety disorders were not more critical toward their children in an observed play situation.

Taken together, although parental anxiety is generally regarded as one of the environmental factors affecting child anxiety-enhancing parenting such as overcontrol and rejection, evidence is inconsistent. However, the environmental effect of parental anxiety on child anxiety might be explained by the effect of parental anxiety on coparenting.

Third, with regard to the association between coparenting and parents’ own anxiety, there are very few studies that directly investigate this relationship. In the Children in the Community Study, a community-based longitudinal study exploring the impact of parental psychiatric disorders in 872 families, paternal anxiety disorder was associated with maternal report of lower assistance of their wives, frequent loud arguments with their wives, and poor fulfillment of family roles (Johnson et al. 2004), which can be regarded as indicators of poor coparenting. In the same sample, maternal anxiety disorder was associated with maternal report of frequent loud arguments with the father (though not after controlling for covariates; Johnson et al. 2006). Isacco et al. (2010) studied fathers’ perceptions of maternal coparental support in a sample of 2062 fathers from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being study, 1 year post birth. Paternal anxiety and depressive symptoms, measured using the CIDI-SF interview sections generalized anxiety disorder and depression, were negatively correlated with fathers’ perceptions of mothers’ coparental support. The effect size of the association was −.28 for married fathers and −.44 for non-married fathers. Unfortunately, no results were reported of depressive and anxiety symptoms separately, as father anxiety and depression loaded onto one latent variable. Note that fathers’ perception of coparenting was measured using a 5-item self-developed scale with unknown validity (an example of an item is “The mother respects the schedule and rules established by you”). In sum, the few studies on parental anxiety and perceived coparental support in infancy support the idea that paternal anxiety is associated with less coparental support. Research on the effects of maternal anxiety on coparental support is even scarcer, as is research on other dimensions of coparenting.

Addressing the association between coparenting and parental anxiety later in childhood, Bögels et al. (2008) conducted a study in which 121 children referred with anxiety disorders and 38 control children, aged 8–18, had two discussions with both their parents; one focusing on a conflictual issue, and one on a child anxiety-related issue. Fathers’ and mothers’ own anxiety disorders were also measured using a structured interview. Coparenting was assessed as partner conversation dominance (measured by the quantity of talking of one parent relative to the other parent) and supportive/undermining coparenting (measured as warmth and support versus rejection of the partner). Results on the relations between parental anxiety and coparenting were analyzed using the anxiety-disordered group of children, so that any effect of parental anxiety disorder on (co)parenting can be viewed as a parental anxiety by child anxiety interaction (see Murray et al. 2009). Results showed that fathers with anxiety disorders dominated the conversation relative to mothers, with a medium effect size (d = .55). This paternal domination was associated with more paternal overcontrol of the child (r = .44). No such effect was found for mothers with anxiety disorders. Thus, the results of Bögels et al. (2008) partially support the hypothesis that parental anxiety disorder is related to less functional coparenting. That is, only anxiety-disordered fathers, but not mothers, showed partner conversation dominance while interacting with their child, suggesting that being anxious interfered with listening and giving space to their partner. The finding that paternal anxiety disorder was associated with partner conversation dominance and with overcontrol of the child, and that partner conversation domination was associated with more overcontrol of the child, suggests that parental anxiety may affect parenting and coparenting behavior in similar ways and that parenting and coparenting behaviors may influence each other bidirectionally. No support was found for parental anxiety disorder being associated with supporting versus undermining the partner in the presence of the anxious child.

In sum, the few studies that address the relation between parental anxiety and coparenting provide some evidence of a negative association between fathers’ anxiety and the coparental relationship. Research on the association between marital functioning and adult or partner anxiety provided indirect evidence pointing in the same direction. The modest associations found between parental anxiety and parenting, and the links of both with coparenting (Bögels et al. 2008) suggest complex interactions between coparenting and parenting in the relation with parental anxiety.

The Effect of Child Anxiety on Coparenting

Although research has mainly focused on the effects of parental factors on child anxiety, there is evidence to suggest that a causal arrow also points in the opposite direction—that is, child anxiety affecting parental factors. The results presented below demonstrate that child anxiety, as measured by its temperamental predispositions or by anxious complaints, indeed affects coparenting. First, the mechanisms that may explain the effect of child anxiety on coparenting are presented.

Models and Mechanisms

Child anxiety and its temperamental predispositions are likely to adversely influence coparenting by inducing increased insecurity, stress, and conflict in the coparenting relationship. Feinberg (2003) described how difficult, or reactive, child temperament may negatively affect the coparenting relationship. The mechanisms that Feinberg described may also hold for the relation between child anxiety and coparenting. He reasoned that children with a difficult temperament most likely demand more focused parenting and coparenting efforts and flexibility, because they are not soothed as easily as other children and parenting strategies may seem to fail. Consequently, the higher frequency of failures in parenting will result in more opportunities for interparental criticism and undermining. Furthermore, in an attempt to adequately deal with a temperamentally difficult child and reduce associated parental stress, parents may consider and attempt a wider range of parenting strategies, which will lead to more frequent situations where they evaluate their rearing strategies. As a consequence, parents’ differences on childrearing issues will become urgently apparent and more opportunities for parental disagreement will arise.

In addition to Feinberg’s (2003) explicitly proposed mechanisms regarding the effect of difficult temperament on coparenting, his review gives rise to the idea that the parental stress caused by the reactive temperament increases the risk of father withdrawal, which in turn may lead to imbalance in parents’ triadic interactions. Furthermore, increased interparental conflict arising as a consequence of dealing with a temperamentally reactive child may facilitate the formation of coalitions and/or triangulation. Finally, it is likely that parenting a child with a reactive temperament requires more time and effort, which puts extra pressure on the available time for parents’ own leisure activities and shared couple activities. Such strains, along with the increased stress of providing care for the child, may increase parents’ dissatisfaction with the division of labor.

Alternatively, a child’s anxiety problems and associated temperamental predisposition may positively affect the coparenting relationship. For example, through intensive cooperation in the management and guidance of their child in dealing with his/her anxiety problems, parents may grow closer and strengthen their relationship, including their coparenting relationship. Crockenberg and Leerkes’ (2003) transactive model of child temperament and family relationships predicts positive as well as negative associations between temperament and coparenting. In this model, psychological preparedness for parenthood, both individually and as a couple, is hypothesized to affect the association between a child’s temperament and coparenting. More specifically, Crockenberg and Leerkes’s (2003) model suggests that child temperamental reactivity may adversely affect coparenting only in conjunction with other risk factors related to family members or family contexts and may even positively affect coparenting when such risk factors are absent.

Empirical Findings

The majority of studies about the effect of child anxiety on coparenting report on the prospective association between the temperamental predisposition for anxiety, that is, behavioral inhibition or a reactive temperament, and coparenting. Of note, several studies used the term difficult temperament, which, in most cases, is identical to reactive temperament. Difficult temperament is characterized by negative emotionality and distress proneness (Clark et al. 2000) and demonstrates overlap with the behavioral inhibition construct. In some cases, though, difficult temperament was defined more broadly. Studies using a broader definition are indicated in the text.

Several studies found an adverse effect of child reactive temperament on coparenting. Most studies reported direct negative associations between a reactive temperament and quality of coparenting and thus support Feinberg’s (2003) hypothesis. Of note, these associations were found more often for paternal coparenting (i.e., father’s observed behavior, or mother’s perception of fathers’ behavior) than for maternal coparenting. Four studies found associations between child reactive temperament and paternal coparenting. First, Lindsey et al. (2005) found that fathers of difficult (i.e., fussier, less adaptable, more persistent, and less sociable as rated by mothers) 14-month-old infants demonstrated relatively greater observed intrusive (or undermining) coparenting. Second, Gordon and Feldman (2008) reported that fathers with temperamentally more difficult (i.e., less predictable as judged by fathers) 5-month-old infants demonstrated less coparental mutuality (similar to support) observed in triadic interactions. Third, Burney and Leerkes (2010), who studied 6-month-old infants and their parents, found a positive association (r = .28, p < .01) between maternal reports of infant soothability and quality of paternal coparenting (operationalized as greater sense of teamwork, respect, and positive communication; mother report). They also found that maternal report of infant reactivity was linked with mother reports of lower quality of paternal coparenting, less father involvement in child care activities, and diminished maternal satisfaction with the division of parenting. Fourth, Kamp et al. (2010) found that maternal reports of reactive temperament in 1-year-old infants were associated with less paternal supportive coparenting (mother report).

One study reported a direct association between child reactive temperament and coparenting exclusively in mothers and two studies found associations in both parents. First, van Egeren (2004) reported that reactivity in 6-month-old infants (father rating) was associated with less positive maternal coparenting (operationalized as a composite representing respect for parenting judgments, support, satisfaction with work division, and perceived joint family management; father rating; r = −.31, p < .01). Second, Davis et al. (2009) found that maternal report of temperamental difficulty (i.e., fussier, less adaptable, more dull, and less predictable) in 3.5 month-old infants was related to less supportive coparenting behavior in both parents (family rating, r = −.26, p < .05). Furthermore, paternal report of infant difficulty at 3.5 months was associated with a reduction of supportive coparenting behavior (both parents) between 3.5 and 13 months. Third, in one of the few studies that looked beyond infancy, Cook et al. (2009) reported a positive association between parent-reported negative emotionality, including sadness and frustration, in 4-year-old children and perceived and observed undermining coparenting in both parents.

Our review of the literature yielded only one finding that was inconsistent with the hypothesis that a reactive temperament is directly associated with more adverse coparenting: Davis et al. (2009) reported a negative association between temperamental difficulty (see above; father rating at 3.5 months) and observed undermining coparenting behavior (both parents; r = −.33, p < .05). Interestingly, as described above, families with a difficult infant also demonstrated lower supportive coparenting, suggesting that parents with a temperamentally difficult child interacted less with each other during coparenting instances, resulting in less undermining as well as less support. Although representing only one finding, this may suggest that parents either withdraw from each other or have less time to interact given increased child needs.

We found three studies that supported Crockenberg and Leerkes’ (2003) model, which suggests a negative effect of child temperament only or particularly in families experiencing other family-related risk factors, such as a lower quality of the prebirth couple relationship in their study. First, McHale et al. (2004a), who studied early coparenting dynamics in association with prebirth couple characteristics and infant temperament at 3 months, found that infant negative reactivity (mother report) interacted with couples’ prebirth functioning to predict postpartum coparenting behavior. More specifically, maternal pessimism about the future coparenting relationship was negatively associated with postpartum observed coparenting cohesion (consisting of cooperation, competition, and family warmth), but only in families with highly reactive infants (r = −.63, p < .05). Furthermore, the positive relation found between prebirth marital quality and coparenting cohesion at 3 months was also solely found in families with highly reactive infants (r = .71, p < .05). Similarly, Schoppe-Sullivan et al. (2007) found that the association between a reactive temperament in 3.5-month-old infants and the quality of observed coparenting was moderated by the prebirth quality of the couple relationship. In their study, parents of reactive infants (as rated by parents and observers) showed more undermining and tended to demonstrate less supportive coparenting behavior only when they had a poorer couple relationship before their infant’s birth, whereas parents of reactive infants with strong prebirth couple relationships demonstrated less undermining and more supportive coparenting. Third, Burney and Leerkes (2010; see also above), who examined parental factors and temperamental reactivity in 6-month-old infants, also found prenatal marital functioning to moderate the association between infant temperament and coparenting. In this study, fathers reported more negative maternal coparenting (i.e., less support and joint family management) when they rated their infant as highly reactive and when they considered the quality of their prenatal marital relationship to be low. Moreover, they reported more positive maternal coparenting (i.e., more support and joint family management) when their infant was highly reactive and they considered the quality of their prenatal marital relationship to be high.

The results of one study, that is, the study of Cook et al. (2009; for details see above) are clearly in contrast with Crockenberg and Leerkes’ (2003) interactional risk model. In addition to the direct effect of negative emotionality on coparenting, Cook et al. also found marital adjustment to moderate this association, but in the opposite direction as predicted from Crockenberg and Leerkes’ (2003) model. That is, parent-rated negative emotionality in preschoolers was associated with lower observed and self-reported supportive coparenting only in families reporting higher levels of postnatal marital adjustment. Finally, only in Stright and Bales’ (2003) study on families with preschoolers, no significant role of children’s difficult temperament in the quality of coparenting (supportive and unsupportive coparenting; observations or self-reports) was detected (r < −.18, ns). The authors themselves argue that their study may have suffered from a relatively restricted range of temperament and limited power to detect interactions.

Studies that model the specific effect of child anxiety (rather than its predispositions) on coparenting are to our knowledge absent. Initial support for the effect of child anxiety on coparenting can be inferred from cross-sectional studies using correlational analyses linking child anxiety and coparenting. For example, in Bögels et al.’s (2008) study that was discussed earlier, fathers (but not mothers) of anxiety-disordered children (aged 8–18), as compared to fathers of typically developing children, were significantly more undermining or less supportive of their partner in the presence of the child during a triadic discussion (d = .35). Similarly, in a study on internalizing problems in 7–12 year-old children and coparenting behavior of their parents, McConnell and Kerig (2002) found internalizing problems in the child to be positively related to observed unsupportive coparenting. More specifically, they found positive associations in boys between maternal report of internalizing problems and hostile-competitive coparenting (r = .36, p < .05) and between self-reported child anxiety and hostile-competitive coparenting (r = .42, p < .05). In addition, they found a positive correlation in girls between maternal report of internalizing problems and parenting discrepancy (i.e., unbalanced coparenting; r = .42, p < .05). In sum, studies measuring the temperamental predisposition of anxiety (i.e., reactive or difficult temperament) suggest that child anxiety indeed negatively affects the coparenting relationship, although the cross-sectional nature of most studies obscures the direction of effects. Four out of 10 studies (Burney and Leerkes 2010; Davis et al. 2009; McHale et al. 2004a, b; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007), though, demonstrated that a reactive temperament in combination with other positive family factors can also have positive effects on the quality of coparenting. Furthermore, more studies reported negative effects of child reactive temperament on paternal coparenting behavior (observed or perceived by the mother) as compared to maternal coparenting behavior, which suggests that paternal coparenting is more strongly affected by a child’s reactive temperament. We further address this issue in the conclusion.

The Effect of Coparenting on Child Anxiety

Recently, there has been a growing interest in how the coparenting relationship shapes child adjustment and/or maladjustment (see Teubert and Pinquart 2010). The present section addresses this development by focusing on coparenting and its potential role in child anxiety. The existing literature has shown that coparenting is of considerable importance for child and family outcomes (Belsky et al. 1996; McHale and Rasmussen 1998; Heinrichs et al. 2010; Teubert and Pinquart 2010). Models and mechanisms on the way coparenting may affect child anxiety are addressed first.

Models and Mechanisms

Dysfunction in each coparenting dimension may create maladaptive family environments that may either alone or in interaction with other factors give rise to increased anxiety in children. In particular, inadequately resolved disagreements, hostility, and interparental conflict associated with dysfunctional coparenting may promote the child’s perceptions of the environment as insecure, hostile, or threatening, which in turn fosters anxiety in the child. Some authors have suggested a parallel between the manner in which conflict is expressed in the coparenting relationship and possible trajectories of problem behavior (Buehler et al. 1998; McHale and Rasmussen 1998). According to this view, if parents use passive-aggressive ways of managing conflict (i.e., covert conflict), the child is more likely to develop internalizing problems, as opposed to externalizing problems. Emotional security theory emphasizes the importance of the role of coparenting unit in maintaining children’s sense of emotional security (Davies et al. 2006; Davies and Cummings 2006). According to the sensitization hypothesis (Davies and Cummings 2006), prolonged exposure to interparental conflicts sensitizes children to concerns about emotional security and affects children’s behavioral and physiological reactions to later interparental conflict. Repeated exposure to interparental conflict is expected to intensify children’s reactivity to it because their sense of emotional security is repeatedly broken. This suggests that, via emotional security, early coparenting conflict may predispose young children to the development of anxiety disorders.

We hypothesize that difficulty in each dimension of coparenting may lead to an insecure, anxiety-provoking environment for the child. First, communication between unsupportive, undermining coparents is likely to be characterized by criticism, disparagement, and blame (Feinberg 2003). Expression of coparental conflict in this way may induce the child’s fear of parental separation resulting in insecurity. Similarly, disagreements on child-rearing issues may more readily result in conflictual coparental interactions on these issues (e.g., Belsky et al. 1995). Dissatisfaction with the division of child-related labor may foster child insecurity and anxiety in particular when the dissatisfaction results in inter-parental disagreements about child-related duties (e.g., putting the child to bed) because these disagreements may make the child feel unloved or unworthy. When conflict leads to withdrawal of one parent, imbalance in triadic family interactions may occur, facilitating the formation of coalitions and/or triangulation. This, in turn, may induce stress and anxiety in the child, for example because the child feels pressured to take a stand for one parent at the expense of losing the support of the other parent. In sum, coparental interactions may be a source of chronic or extreme conflict (Feinberg 2003), both likely to induce anxiety.

However, a noteworthy alternative hypothesis suggests that some dysfunction in the coparenting environment may have positive effects on child behavioral inhibition and anxiety (Belsky et al. 1996). Based on the finding that a certain extent of insensitive and negative parenting reduces behavioral inhibition (Park et al. 1997), Belsky et al. (1996) argue that moderate levels of coparental undermining may toughen up highly reactive children who are at risk for behavioral inhibition and anxiety. According to this view, when fathers and mothers behave differently toward the child and/or fail to support each other, highly reactive children are “prodded” to change their behavior and become less inhibited (Belsky et al. 1996). Belsky et al. (1996) describe an example that illuminates the potential mechanism of this positive effect. When a child falls and his mother comforts him, but his father conveys that mother is spoiling him and that he shouldn’t cry, the child may learn that his behavior fosters conflict between his parents and consequently may try to “toughen up” to prevent such conflict in the future. Thus, it is important to consider the potential beneficial effects of negative coparenting on child anxiety—at least for some children.

Empirical Findings

In a recent meta-analysis, the effect of coparenting on child adjustment, including internalizing problems, was examined across 59 studies (Teubert and Pinquart 2010). Coparenting was operationalized using four dimensions, that is, coparental cooperation, agreement, conflict, and triangulation. Small but significant mean effects on child internalizing symptoms were found for coparenting cooperation (r = −.13), agreement (r = −.20), conflict (r = .19), and triangulation (r = .21). These effects remained significant after controlling for the quality of parenting and the marital relationship. Furthermore, several moderators of the relation between coparenting and internalizing behaviors emerged, namely age (larger effects for younger children) and family structure (larger effects for divorced families). Thus, this meta-analysis provided evidence that coparenting dimensions are linked to internalizing problems as we hypothesized above. Similarly, the review of Heinrichs et al. (2010) reported that various aspects of couple functioning, including coparenting and interparental conflict, affect child emotional and behavioral problems, including internalizing problems and anxiety.

Several studies examined associations between coparenting and child reactive or difficult temperament. Cross-sectional studies reporting the hypothesized link between coparenting and child anxiety were described in the section above on the effects of child anxiety on coparenting. Three of those studies found positive relations between (mainly) paternal coparenting behaviors and infant or child negative reactive temperament (Lindsey et al. 2005; Cook et al. 2009; Burney and Leerkes 2010), one study reported non-significant and marginally significant associations (Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007) and one study found no associations (Stright and Bales 2003).

Two studies addressed prospective relations between coparenting and child temperamental predispositions to anxiety. Davis et al. (2009) observed coparenting during triadic free-play. In the model assessing the effect of supportive coparenting on the course of infant difficulty, supportive coparenting at 3.5 months after birth predicted decreased infant difficulty from 3.5 to 13 months, as rated by fathers, but not mothers. Interestingly, raw correlations from Davis et al. (2009) suggested a negative association between undermining coparenting and paternal perceptions of infant difficulty at 3.5 months. Pauli-Pott and Beckmann (2007) investigated the role of observed child negative emotionality at 4 months and parent-reported coparental conflict in predicting observed behavioral inhibition at 30 months. A summary score of coparental conflict measured when children were 4, 8, and 12 month-old explained unique variance in toddler behavioral inhibition at 30 months (r = .38, p < .05), above the effects of infant negative emotionality at 4 months.

Three studies directly assessed the relation between coparenting and child anxiety (as opposed to its temperamental precursors). First, Bögels et al. (2008; also discussed in the previous section) found that fathers of anxiety-disordered children were significantly more undermining of their partner in observed discussions than fathers of control children. Of note, the effect size of paternal undermining was the largest difference in parental behaviors found between families with children with an anxiety disorder versus control children; effect sizes for parenting behaviors toward the child (control, rejection) were smaller and non-significant. Second, McHale and Rasmussen (1998) reported that parental discrepancy in warmth and investment during observed triadic play at child age 8–11 months predicted greater teacher-rated child anxiety 3 years later (r = .38, p < .05). Third, in McConnell and Kerig’s cross-sectional study (2002; also discussed in the previous section), positive associations of observed hostile-competitive coparenting with self-rated child anxiety were found for boys (r = .42, p < .05).

As mentioned above, some specificity has been proposed with respect to the effects of the way in which coparental conflict is expressed in the family (Buehler et al. 1998; McHale and Rasmussen 1998). In an empirical study exploring this hypothesis in two large samples of children aged 9–15, Buehler et al. (1998) found an association between child-rated covert parental conflict and internalizing problems in both samples. Overt conflict did not predict internalizing problems. As mentioned above, McConnell and Kerig (2002) found positive associations of observed (overt) hostile-competitive coparenting with boys’ self-rated anxiety, and also with mother-rated internalizing problems of boys (r = .36, p < .05). In contrast, McHale and Rasmussen (1998) reported no associations between observed hostile-competitive parenting and internalizing disorders.

The above studies suggest that both covert and overt forms of coparental conflict can give rise to child anxiety, but the evidence is stronger for covert conflict. It may be that the existence of covert conflict is the result of long-standing, entrenched, chronic conflict. Covert conflict may be linked to withdrawal from overt conflict—and interparental withdrawal has been found to represent an advanced stage of chronic conflict that has particularly negative repercussions (Cox et al. 1999). Moreover, covert conflict may prevent resolution that reduces child stress (Cummings et al. 1991). Finally, covert conflict by its nature may leave the child feeling alone and isolated in his or her perception of conflict and insecurity, or in his/her inability to articulate, understand, or receive support for experiencing covert conflict.

In contrast to the above findings that negative coparenting is associated with anxiety or its temperamental precursors or internalizing problems, support for the alternative hypothesis that a certain level of negative coparenting may decrease child behavioral inhibition and anxiety (Park et al. 1997; Belsky et al. 1996) comes from two studies. First, Belsky et al. (1996) reported that coparents of the subgroup of boys who had become less behaviorally inhibited at 3 years than expected (from their reactivity in infancy) showed the highest level of observed unsupportive coparenting, whereas coparents of boys who had become more inhibited than expected showed the lowest levels of unsupportive behavior (note that in the same sample, higher levels of negative parenting of the father also predicted less behavior inhibition in boys; Park et al. 1997). Second, as already mentioned above, the correlational (but not path analysis) results of Davis et al. (2009) indicated a negative association between undermining coparenting and infant difficult temperament.

In sum, the majority of studies on the association of coparenting with child internalizing problems, reactive temperament, or anxiety, suggest that dysfunction in coparenting negatively affects child anxiety. Only two studies (Davis et al. 2009; Belsky et al. 1996) reported positive effects of negative (i.e., undermining) coparenting on child reactivity, suggesting that negative coparenting environments may be beneficial for highly reactive children. In line with the previous sections, some evidence was found for a stronger role of (maternal perceptions of) paternal than maternal coparenting behaviors on child anxiety.

Conclusions and Integration, Future Directions, and Clinical Implications

We have discussed potential mechanisms and empirical findings regarding the relation of parent or child anxiety and coparenting. In general, the findings are consistent in that anxiety among family members is negatively related to supportive and adaptive coparenting. For example, the few available studies and circumstantial evidence suggest that paternal and perhaps maternal anxiety is linked to low coparental support. Overall, the research reviewed also suggests the existence of inverse links between children’s anxiety and coparenting quality. This research is generally supported by similar findings of inverse links between coparenting quality and anxiety-related constructs such as the temperamental precursors of anxiety (e.g., reactive temperament) and the broader domain of internalizing problems. There were some exceptions to this general pattern of child anxiety linked to more problematic coparenting. Two studies found evidence that coparenting difficulties may be linked to less anxiety (Belsky et al. 1996; Davis et al. 2009). In addition, a moderation effect was found that was consistent with Crockenberg and Leerkes’ (2003) transactional model: Among families with relatively high levels of resources and coping capacity, a reactive child temperament appeared to bring these parents together in a more supportive coparenting relationship. Whether child anxiety has the same effect among well-resourced families is currently unknown.

Thus, the majority of studies point to bidirectional relations between greater coparenting difficulties and higher levels of child anxiety, although there is some mixed evidence suggesting coparenting difficulties are associated with lower child anxiety.

The Role of Fathers Versus Mothers

In all sections, research pointed toward differences in effects between fathers and mothers. In the research on parental anxiety, evidence was found of an association between one aspect of coparenting, namely partner conversation dominance, and parental anxiety for fathers but not for mothers (i.e., Bögels et al. 2008). Taken this finding one step further, anxious fathers may tend to control the coparenting relationship (which was associated with more paternal control of the anxious child), whereas anxious mothers may not. That same study also found that in families with anxious fathers, mothers were relatively less supportive or more rejecting toward their anxious child. Non-anxious fathers may communicate confidence by supporting and listening to their partner, rather then by being dominant, which may help mothers to be more accepting and supportive of the child. This pattern represents a triadic interaction sequence.

Children’s anxiety (or reactive or difficult temperament) appeared consistently more detrimental for fathers’ coparenting than mothers’ coparenting behaviors. One explanation for this pattern may be based on the different roles fathers and mothers are assumed to have in childrearing. In the model of Bögels and Phares (2008), it is argued that via challenging parenting behavior, fathers have a particularly important influence on children’s social competence. These differences between fathering and mothering may be rooted in evolutionary benefits to parenting specialization (Bögels and Perotti 2011). In line with this, fathers use more boisterous and active play approaches with children than do mothers (MacDonald and Parke 1986), and fathers tend to focus on preparing children to interact with the world outside the family (Paquette 2004). Additionally, one can argue that child anxiety poses greater difficulties for children’s engagement in the outside world than in the family sphere. For example, anxieties and phobias more commonly relate to extra-familial factors (e.g., strangers, unfamiliar social/school situations, animals, environmental factors such as darkness or heights, etc.) than familial factors (other family members, family routines). Child anxiety may be seen to interfere to a greater extent, then, with fathers’ childrearing goals and activities compared to those of mothers. Moreover, child anxiety may elicit mothers’ (protective) involvement (e.g., Moore et al. 2004), leading to conflict with fathers over childrearing approaches. As this coparenting conflict may focus on children’s engagement in activities outside the family, the conflict may be particularly salient for fathers given their tendency to focus on such engagement.

In line with the above argument, a child’s reactive temperament may result in paternal withdrawal from the family system. Van Egeren (2001) proposes the existence of both a direct and an indirect pathway between the child’s anxious predisposition and paternal withdrawal. According to van Egeren, the level of father involvement in parenting and coparenting is contingent upon both the father’s motivation and the mother’s acceptance versus resistance to such involvement—referred to as maternal gatekeeping. A reactive infant may tend to diminish fathers’ motivation to be involved with their child, resulting in coparental conflict over father’s withdrawal from parenting responsibilities. In addition, the mother’s increased protective tendencies elicited by the reactive infant may result in increased maternal gatekeeping and resistance to the more boisterous fathering style of involvement.

Toward an Integrated Model of Family Functioning and Individual Psychopathology

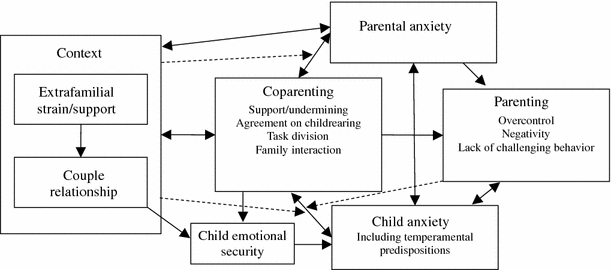

Despite the fact that the research is limited, particularly for some of the relations examined here, the evidence suggests that parent and child anxiety are indeed related to coparental quality—generally in an inverse manner. This relationship has been reported by studies that have taken a number of approaches to assessing coparenting, including dimensional and composite measures, and through both self-report and observation. The existing evidence encourages us to propose several ideas about the differential mechanisms underlying the relation of parent versus child anxiety with coparenting, resulting in a conceptual model that may represent an intermediary framework to guide future research (Fig. 1). It is based on Feinberg’s (2003) ecological model of coparenting, which could be revised and refined as a result of the current discussion on anxiety. The specific focus on anxiety shows the model’s usefulness for illuminating the role of coparenting in the development and maintenance of a specific trait, complaint, or disorder.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model linking coparenting and parent and child anxiety. Dashed lines are moderators

Parental Anxiety

As hypothesized above, parental anxiety may directly interfere with positive coparenting as, for example, anxiety prevents a parent from engaging fully in problem-solving with a partner. Parent anxiety may also be related to general relationship problems as couples struggle to compensate for the functional limitations or emotional reactivity introduced by one partner’s anxiety. These general relationship problems, such as hostility or withdrawal, may then affect couples’ ability to coparent effectively. It is also possible that parental anxiety problems result in elevated concerns about child activities and exposures, which then lead to childrearing disagreements and heightened coparental conflict.

Coparental conflict may also lead to increased anxiety symptoms in parents. First, a generalized effect of stress may exacerbate an underlying vulnerability to anxiety problems. Second, conflict within the interparental relationship—which has been viewed in terms of an attachment relationship providing security for each partner (Mikulincer et al. 2002; Simpson et al. 1992)—may undermine parental emotional security and lead to increased anxiety. Third, parents may identify strongly with the well-being of their child; consequently, childrearing disagreements may involve a perception that the other parent is not maintaining a safe environment for the child, thus leading to increased anxiety on the part of the parent identifying with the child.

Child Anxiety

Above, we developed hypotheses for the relations of various dimensions of coparenting with child anxiety and do not repeat these here. In general however, child anxiety (and its temperamental precursors) may lead to intensified coparenting engagement with the potential for increased conflict. In the face of child anxiety, parents may withdraw from coparenting engagement to avoid conflict. Although withdrawal is not equivalent to covert conflict, it is possible that withdrawal often involves covert conflict. Moreover, there may be different implications of covert versus overt forms of coparental conflict for child anxiety as we have discussed above. Thus, there may be reciprocal and even spiraling cycles of child anxiety leading to coparental conflict, leading to further increases in child anxiety. Such cycles may be quite difficult to document without study designs that involve closely spaced measurement occasions (including daily diary approaches) or experimental (i.e., intervention) manipulation.

Given the evidence discussed above of the importance of fathers’ anxiety for coparenting, coparenting may be especially likely to affect fathers’ parenting behaviors. Consequently, coparenting difficulties may interfere with parenting behavior that is typical for fathers and is assumed to particularly affect children’s anxiety, such as challenging the child to take risks (Bögels and Phares 2008; Bögels and Perotti 2011; Bögels et al. 2011).

Attention to potential mediators of these relations will be important. For example, work has explored the role of emotional security of the child as a mediator of the link between family conflict and child adjustment such as depression and behavior problems (Davies and Cummings 1998; Restifo and Bogels 2009). It is likely that emotional security would be a particularly strong mediator for child anxiety.

In addition to these pathways, family and extra-familial contextual factors may moderate relations between anxiety and coparenting—as we have noted above in the case of couple conflict before the birth of the child. For example, parenting quality—both parenting that promotes emotional security as well as parenting behaviors that may be specifically related to child anxiety, such as overcontrol—may moderate the effects of coparenting on child anxiety. Conversely, coparenting may moderate the effects parenting on child anxiety. Parent age and experiences in the family of origin may also moderate the relations of interest, as young parents and those with a history of abuse or family conflict may be less able to function well under the strains of either coparental conflict or family member anxiety. Finally, extra-familial factors such as financial strain and social support may reduce the ability of parents to coparent or parent successfully in the face of anxiety problems. Understanding the moderating roles of such factors described here may help both in identifying families requiring support and in guiding the type of support and intervention that may be most helpful.

We have not discussed genetic factors that may underlie associations between family relationship and individual mental and behavioral problems (Reiss et al. 2000). However, we recognize that some covariation of family relationships and anxiety problems may be due to genetic factors. Of more interest may be the way that genetic factors influence either anxiety or family relationships, which then may influence the other construct, as well as the way genetic factors may moderate the relations between anxiety and coparenting. Further discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Future Research Directions

The conceptual model discussed above provides guidelines for future research. Relations between anxiety and coparenting that have been understudied but are potentially important include the relation between parental (including maternal) anxiety and coparenting, particularly the influence of coparenting on parental anxiety. Furthermore, without ignoring negative influences, future research may also focus on potential positive influences of ‘negative’ coparenting on child anxiety (i.e., what levels of undermining coparenting might ‘toughen up’ a child; Belsky et al. 1996) or of child anxiety on the coparenting relationship. As an example of the latter, working together on the anxiety problem of their child may also have far-reaching effects on parents by reducing their own anxiety problems.

Given support for interparental differences in relations between coparenting and anxiety, future research should distinguish between fathers’ and mothers’ coparenting behaviors. It is helpful to clearly specify the target of coparenting measures. For example, maternal perceptions of coparenting may include father’s coparenting-related behavior, aspects of the dyadic coparenting dynamics, or satisfaction with father parenting, satisfaction with father coparenting behaviors, or satisfaction with dyadic coparental dynamics. Even if a measure focuses on actual paternal coparenting behaviors, potential relations with child anxiety, for example, may be partly explained by an informant perception bias. When using observations, researchers may consider utilizing separate indices of fathers’ and mothers’ coparenting behaviors instead of aggregating these into a single construct.

In line with these measurement issues, both coparenting and anxiety should be assessed more specifically. The coparenting dimension of support versus undermining is the most frequently studied aspect of coparenting. A more differentiated and valid picture about the relations between anxiety and coparenting may emerge when other coparenting dimensions (i.e., joint family management, agreement on parenting, and division of labor) are also included. As regards child anxiety, much research has relied on fairly broad indices of child reactive/difficult temperament or internalizing problems instead of child anxiety complaints or disorders. Thus, it would be beneficial to separately consider the contribution of distinct coparenting dimensions to narrower constructs of child adjustment. This approach has proven successful in former studies (e.g., partner conversation dominance and child anxiety disorder in Bögels et al. 2008).

Finally, as highlighted in research on anxiety (e.g., Murray et al. 2009), there is a continuous interaction between child and parental factors (including parental anxiety and parenting) in the development of anxiety. As the coparenting relationship is developing over time as well (Feinberg 2003), this transaction will also involve coparenting dynamics. However, the majority of studies rely on correlational analyses between coparenting and child or parental anxiety measured at one point in development. Given the complexity of the direction of effects, stronger designs involving multiple longitudinal measurements of coparenting and anxiety are needed to infer causality and to take into account these transactional influences.

Clinical Implications

Although the literature base on anxiety and coparenting is limited, there are a few clinical implications that we can draw at this point. For example, in the light of evidence that child anxious temperament influences coparenting, and given our knowledge that—even in infancy—children affect the early course of the family processes that in turn affect their development (e.g., Davis et al. 2009), it seems that clinicians should be aware of the reciprocal relations between child anxiety/anxious temperament and coparenting quality. Families presenting for treatment who report child anxiety, and even those who report temperamentally difficult infants, should be assessed for difficulties in coparenting relations and coordination. Although clinical approaches to bolstering coparenting quality may be called for, it may also be the case for some parents that simply providing information about the potential effects of child temperament and anxiety on coparenting may facilitate decreased blame and conflict within the interparental relationship. Moreover, clinicians should be aware of the contribution of, or exacerbation of, parental anxiety in relation to coparenting difficulty and conflict. Accordingly, treatment of anxious parents should include an assessment of the presence of difficulties in coparenting relations (as well as in parent–child relations).

Finally, the existing evidence also suggests that clinicians may include both parents in treatment when coparenting difficulties are or may become present in combination with anxiety but that one may need to tailor interventions differently for fathers and mothers. That is, therapists need to explain (to fathers and mothers) that parents differ and may have unique roles in helping anxious children to overcome anxiety, as well as explain that differences in mothers’ and fathers’ approach (e.g., mothers being more protective and fathers being more challenging) may be healthy and helpful. Rather than differences between fathers’ and mothers’ approach becoming a source of polarization, conflict, and undermining coparenting, such differences can, in a supportive coparenting relationship, be applied to the child’s advantage (e.g., Bögels and Siqueland 2006). More clarification on treating anxious family members and difficult coparenting relations simultaneously awaits further research.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of Mirjana Majdandžić, Wieke de Vente, and Susan Bögels were supported by an Innovation Research Vici NWO grant, number 453-09-001, to Susan Bögels, and the contribution of Evin Aktar by the research priority program Brain and Cognition.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged 4 through 16. Monographs of Social Research in Child Development. 1981;46:188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. doi: 10.2307/1131939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting and early emotional development. New Directions for Child Development. 1996;74:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, Faraone SV. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Bamelis L, van der Bruggen C. Parental rearing as a function of parent’s own, partner’s, and child anxiety status: Fathers make the difference. Cognition and Emotion. 2008;22(3):522–538. doi: 10.1080/02699930801886706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Brechman-Toussaint M. Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;7:834–856. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Perotti EC. Does father know best? A formal model of the paternal influence on childhood social anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2011;20:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Phares V. The role of the father in the development, prevention and treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:539–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Siqueland L. Family cognitive behavior therapy for children with clinical anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:134–141. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000190467.01072.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels, S., Stevens, J., & Majdandžić, M. (2011). Parenting and social anxiety: Fathers’ versus mothers’ influence on their children’s anxiety in ambiguous social situations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, no. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brook CA, Schmidt LA. Social anxiety disorder: A review of environmental risk factors. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2008;4:123–143. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggen CO, van der Stams GJM, Bögels SM. Parental control and parent and child anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1257–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Anthony C, Pemberton S, Gerard J, Barber B. Interparental conflict styles and youth problem behaviors: A two-sample replication study. Journal of Marriage & Family. 1998;60(1):119–132. doi: 10.2307/353446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burney RV, Leerkes EM. Links between mothers and fathers perceptions of infant temperament and coparenting. Infant Behavior & Development. 2010;33:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Kochanska G, Ready R. Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:274–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CJ, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Buckley CK, Davis EF. Are some children harder to coparent than others? Children’s negative emotionality and coparenting relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:606–610. doi: 10.1037/a0015992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Payne CC, Burchinal M. The transition to parenthood: Marital conflict and withdrawal and parent-infant interactions. In: Cox MJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Conflict and cohesion in families: Causes and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Leerkes E. Infant negative emotionality, caregiving, and family relationships. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Ballard M, El-Sheikh M, Lake M. Resolution and children’s responses to interadult anger. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(3):462–470. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.3.462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Exploring children’s emotional security as a mediator of the link between marital relations and child adjustment. Child Development. 1998;69:124–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Interparental discord, family process, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 86–128. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM, Winter MA. Pathways between profiles of family functioning, child security in the interparental subsystem, and child psychological problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:525–550. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple L, Winter MA, Cummings EM, Farrell D. Child adaptational developments in contexts of interparental conflict over time. Child Development. 2006;77(1):218–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EF, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Brown GL. The role of infant temperament in stability and change in coparenting across the first year of life. Parenting. 2009;9:143–159. doi: 10.1080/15295190802656836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3(2):95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filsinger EE, Wilson MR. Social anxiety and marital adjustment. Family Relations. 1983;32:513–519. doi: 10.2307/583691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon I, Feldman R. Synchrony in the traid: A microlevel process model of coparenting and parent-child interactions. Family Process. 2008;47:465–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Clark R. Maternal employment and development of the father–infant relationship in the first year. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:893–903. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N, Cronrath AL, Degen M, Snyder DK. The link between child emotional and behavioral problems and couple functioning. Family Science. 2010;1:152–172. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2010.569366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isacco A, Garfield GF, Rogers TE. Correlates of coparental support among married and nonmarried fathers. Journal of Men & Masculinity. 2010;11:262–278. doi: 10.1037/a0020686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Paternal psychiatric symptoms and maladaptive paternal behavior in the home during the child rearing years. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13(4):421–437. doi: 10.1023/B:JCFS.0000044725.76533.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Maternal psychiatric disorders, parenting, and maternal behavior in the home during the child rearing years. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15(1):97–114. doi: 10.1007/s10826-005-9003-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychological Science. 1991;2:40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1991.tb00094.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitz M, Maytal H. Interactions between anxious mothers and their infants: An integration of theory and research findings. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26(6):570–597. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush, C. M., Kotila, L. E., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2010). Do relationship and child characteristics predict supportive coparenting after relationship dissolution among at-risk parents? Retrieved from http://crcw.princeton.edu/publications/publications.asp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders III: Probability of marital stability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1092–1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey EW, Caldera Y, Colwell M. Correlates of coparenting during infancy. Family Relations. 2005;54:346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00322.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, Parke RD. Parent-child physical play: The effects of sex and age of children and parents. Sex Roles. 1986;15:367–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00287978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell MC, Kerig PK. Assessing co-parenting in families of school-age children: Validation of the coparenting and family rating system. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science. 2002;34(1):44–58. doi: 10.1037/h0087154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, Lieberson R. The transition to coparenthood: Parents’ prebirth expectations and early coparental adjustment at 3 months postpartum. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:711–733. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]