Abstract

Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 is a facultative anaerobic bacterium capable of respiring a multitude of electron acceptors, many of which require the Mtr respiratory pathway. The core Mtr respiratory pathway includes a periplasmic c-type cytochrome (MtrA), an integral outer-membrane β-barrel protein (MtrB), and an outer-membrane-anchored c-type cytochrome (MtrC). Together, these components facilitate transfer of electrons from the c-type cytochrome CymA in the cytoplasmic membrane to electron acceptors at and beyond the outer-membrane. The genes encoding these core proteins have paralogs in the S. oneidensis genome (mtrB and mtrA each have four while mtrC has three) and some of the paralogs of mtrC and mtrA are able to form functional Mtr complexes. We demonstrate that of the additional three mtrB paralogs found in the S. oneidensis genome, only MtrE can replace MtrB to form a functional respiratory pathway to soluble iron(III) citrate. We also evaluate which mtrC/mtrA paralog pairs (a total of 12 combinations) are able to form functional complexes with endogenous levels of mtrB paralog expression. Finally, we reconstruct all possible functional Mtr complexes and test them in a S. oneidensis mutant strain where all paralogs have been eliminated from the genome. We find that each combination tested with the exception of MtrA/MtrE/OmcA is able to reduce iron(III) citrate at a level significantly above background. The results presented here have implications toward the evolution of anaerobic extracellular respiration in Shewanella and for future studies looking to increase the rates of substrate reduction for water treatment, bioremediation, or electricity production.

Keywords: iron respiration, anaerobic, Mtr-pathway, extracellular respiration

Introduction

Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 (MR-1) is a facultative anaerobic bacterium capable of respiring a diverse array of compounds. MR-1 respiration can be harnessed for bioremediation of radioactive heavy metals (Wall and Krumholz, 2006), removal of insoluble metal oxides from wastewater (Fredrickson et al., 2008), and generation of electricity in microbial fuel cells (Lloyd et al., 2003; Lovley, 2008). In respiring insoluble metals and electrodes, MR-1 has evolved a mechanism to transfer electrons from the cytoplasmic space to electron acceptors unable to cross the outer-membrane (OM) termed extracellular respiration (Gralnick and Newman, 2007). The respiratory diversity of MR-1 coupled with well-established genetic tools have made this microbe a model organism for understanding mechanisms of anaerobic respiration; most notably extracellular respiration (Marsili et al., 2008; Von Canstein et al., 2008; Coursolle et al., 2010).

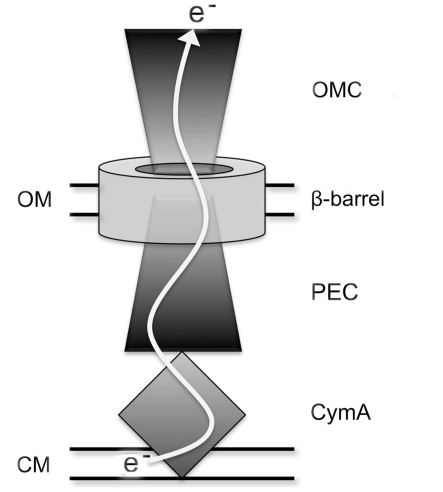

The Mtr respiratory pathway of MR-1 contains interchangeable proteins that can form distinct functional modules for the reduction of iron(III) citrate, iron oxide, flavins, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). A general scheme for how the components of the Mtr respiratory pathway facilitate electron flow in MR-1 is shown in Figure 1. Electron transfer from the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) begins with CymA, a CM-anchored tetraheme c-type cytochrome capable of receiving electrons from the menaquinone pool (Myers and Myers, 1997). Also contained in each module is a periplasmic electron carrier (PEC), which is a decaheme c-type cytochrome. There are three known functional PECs encoded in the MR-1 genome by mtrA, mtrD, and dmsE (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). DmsE is primarily used in modules to reduce the terminal electron acceptor DMSO (Gralnick et al., 2006), but has minor activity in modules that reduce iron(III) citrate (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). MtrA is the primary periplasmic component used by MR-1 when reducing iron(III) and flavins, but overexpression of MtrD can restore ferric citrate reduction rates to an mtrA mutant (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). A fourth PEC is encoded in the MR-1 genome (SO4360) but it has no demonstrated function to date. Recently, small-angle X-ray scattering coupled with analytical ultracentrifugation has resolved that MtrA is shaped like a “wire,” likely making its purpose to shuttle electrons between CymA and OM proteins (Firer-Sherwood et al., 2011). All functional iron(III)-reducing modules also contain an outer-membrane cytochrome (OMC), a decaheme c-type cytochrome which can be MtrC, MtrF, or OmcA (Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). Due to the severely impaired rate of soluble iron reduction in mutants lacking all three OMCs, it has been concluded that all metal reduction occurs outside the cell, even when metal substrates are small enough to penetrate OM porins (Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). A structure of the OMC protein MtrF was recently reported, identifying potential electron transfer pathways directly to insoluble substrates and to soluble flavin electron shuttles (Clarke et al., 2011). The remaining component of a functional Mtr module is an integral membrane β-barrel protein that forms a pore-like structure through the OM that may facilitate direct interaction between PECs and OMCs (Beliaev and Saffarini, 1998; Hartshorne et al., 2009). MtrB is the only protein known to exhibit this function in the Mtr respiratory pathway, though three paralogs (encoding MtrE, DmsF, and SO4359) occur in the genome of S. oneidensis.

Figure 1.

Schematic of extracellular electron transfer pathway in S. oneidensis. OMC represents outer-membrane cytochrome paralogs of MtrC, β-barrel represents MtrB paralogs, and PEC represents periplasmic electron carrier paralogs of MtrA. OM and CM represent OM and CM, respectively.

The biochemical capacities of several Mtr respiratory pathway proteins have been interrogated in vitro. Both MtrC and OmcA have been purified and demonstrated to exchange electrons with each other and various forms of iron(III), flavins, and electrodes (Xiong et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2007; Wigginton et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2009). MtrA has been heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli and can be oxidized in the presence of soluble iron(III; Pitts et al., 2003). Likewise, CymA was shown to have soluble iron(III) reduction activity when expressed in E. coli (Gescher et al., 2008). Components of the Mtr-pathway have been purified and examined using protein film voltammetry to determine redox windows where electron transfer reactions are favorable as single proteins (Firer-Sherwood et al., 2008) and as complexes (Hartshorne et al., 2009). Three primary constraints complicate comparisons between in vitro biochemical analysis and in vivo function of Mtr respiratory proteins: first, orientation of the protein cannot effectively be controlled. Orientation is a critical factor in how Mtr respiratory proteins function given that oxidation and reduction is likely to occur in different active sites of an electron transfer proteins. Second, chemical reductants or electrodes rather than a native pathway must provide electrons for purified proteins. Finally, substrate accessibility in vitro is unhindered in the absence of cellular structure, therefore allowing reactions to occur that may not reflect activity in a living system. In vivo analysis remedies each of these described caveats.

In this study we constructed a S. oneidensis strain unable to reduce Fe(III) citrate by first deleting all genes identified in the Mtr-pathway. Then, using a multi-gene complementation strategy we add back various combinations of Mtr paralogs. In doing this, we identify which of the 48 possible mtrC/mtrA/mtrB paralog modules (from 4 PEC, 4 β-barrel, and 3 OMC paralogs) can form functional iron(III)-reducing modules in vivo. Due to high identity amongst most of these paralogs (Table 1), in conjunction with previous studies demonstrating shared functionality between paralogs (Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010), we expect many recombinant modules to transfer iron(III) reducing capability to our mutant missing all Mtr genes. We find that in reconstructed modules the PECs SO4360 and DmsE do not exhibit significant activity. We also find that the predicted OM β-barrels DmsF and SO4359 cannot complement an mtrB mutant. Lastly, we discover that when functional modules are created, MtrDEF can reduce Fe(III) citrate at approximately half the rate as MtrABC, demonstrating for the first time the functionality of a complete iron-reducing module lacking MtrA, B, and C.

Table 1.

Amino acid identity between Mtr paralogs.

| Gene | PEC (%) |

β-Barrel (%) |

OMC (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtrA | mtrD | dmsE | SO4360 | mtrB | mtrE | dmsF | SO4359 | mtrC | mtrF | omcA | |

| mtrA | 100 | 68 | 64 | 53 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| mtrD | 68 | 100 | 59 | 48 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| dmsE | 64 | 59 | 100 | 51 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SO4360 | 53 | 48 | 51 | 100 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| mtrB | – | – | – | – | 100 | 35 | 35 | 25 | – | – | – |

| mtrE | – | – | – | – | 35 | 100 | 30 | 25 | – | – | – |

| dmsF | – | – | – | – | 35 | 30 | 100 | 29 | – | – | – |

| SO4359 | – | – | – | – | 25 | 25 | 29 | 100 | – | – | – |

| mtrC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 100 | 34 | 21 |

| mtrF | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 34 | 100 | 25 |

| omcA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 21 | 25 | 100 |

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and media used

MR-1 was originally isolated from Lake Oneida in New York (Myers and Nealson, 1988; Venkateswaran et al., 1999). Strains and plasmids used in this study are found in Table 2. Overnight cultures were made from single colonies isolated from a frozen stock inoculated into 2 mL of Luria–Bertani (LB) medium and grown aerobically for 16 h. When necessary, Shewanella basal medium (SBM) was used as minimal medium (Baron et al., 2009). Iron(III) citrate was used as indicated as electron acceptor. Kanamycin was used at a concentration of 50 μg/mL and ampicillin was used at a concentration of 100 μg/mL when necessary. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was used at a concentration of 360 μM for all growth of E. coli strain WM3064. Overnight cultures of E. coli were made from single colonies inoculated into 2 mL of LB and grown aerobically for 16 h.

Table 2.

Strains used in this work.

| Relevant genotype; name used in text | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| STRAIN | ||

| JG274 | MR-1, wild type | Myers and Nealson (1988) |

| JG168 | JG274 with empty pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | Hau et al. (2008) |

| JG700 | ΔmtrB | This work |

| JG1176 | ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA | This work |

| JG1194 (ΔMtr) | ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ΔrecA | This work |

| JG1419 | ΔmtrB/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ | This work |

| JG1452 | ΔmtrE/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ΔrecA | This work |

| JG1453 | ΔmtrB/ΔmtrE/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ | This work |

| JG1485 (ΔMtr/ΔmtrE) | ΔmtrE/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ΔrecA | This work |

| JG1486 (ΔMtr/ΔmtrB/ΔmtrE) | ΔmtrB/ΔmtrE/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ΔrecA | This work |

| JG1519 (ΔMtr/ΔmtrB) | ΔmtrB/ΔmtrC/ΔomcA/ΔmtrF/ΔmtrA/ΔmtrD/ΔdmsE/ΔSO4360/ΔcctA/ΔrecA | This work |

| JG1219 | JG700 with pmtrE, Kmr | This work |

| JG1220 | JG700 with pmtrB, Kmr | This work |

| JG1221 | JG700 with pdmsF, Kmr | This work |

| JG1222 | JG700 with pSO4359, Kmr | This work |

| JG1223 | JG700 with pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This work |

| JG1280 | JG1194 with pomcA/SO4360, Kmr | This work |

| JG1281 | JG1194 with pmrF/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1282 | JG1194 with pomcA/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1283 | JG1194 with pmtrC/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1288 | JG1194 with pmtrC/dmsE, Kmr | This work |

| JG1289 | JG1194 with pmtrF/dmsE, Kmr | This work |

| JG1290 | JG1194 with pmtrF/SO4360, Kmr | This work |

| JG1291 | JG1194 with pmtrF/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1292 | JG1194 with pomcA/dmsE, Kmr | This work |

| JG1293 | JG1194 with pmtrC/SO4360, Kmr | This work |

| JG1294 | JG1194 with pomcA/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1295 | JG1194 with pmtrC/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1489 | JG1485 with pmtrC/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1490 | JG1485 with pmtrF/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1491 | JG1485 with pomcA/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1492 | JG1485 with pmtrC/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1493 | JG1485 with pmtrF/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1504 | JG1486 with pmtrC/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1505 | JG1486 with pmtrF/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1506 | JG1486 with pomcA/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1507 | JG1486 with pmtrC/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1508 | JG1486 with pmtrF/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1525 | JG1519 with pmtrB/mtrF/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1526 | JG1519 with pmtrB/mtrC/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1527 | JG1519 with pmtrB/mtrC/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1528 | JG1519 with pmtrB/omcA/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1529 | JG1519 with pmtrB/mtrF/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1530 | JG1519 with pmtrE/mtrF/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1531 | JG1519 with pmtrE/mtrC/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1532 | JG1519 with pmtrE/mtrF/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1533 | JG1519 with pmtrE/omcA/mtrA, Kmr | This work |

| JG1534 | JG1519 with pmtrE/mtrC/mtrD, Kmr | This work |

| JG1535 | JG1485 with pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| JG1536 | JG1486 with pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| JG1537 | JG1519 with pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| PLASMIDS | ||

| pSMV3 | Deletion vector, Kmr, sacB | Saltikov and Newman (2003) |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Broad range cloning vector, Kmr | Kovach et al. (1995) |

| pBBR-BB | Broad range BioBrick vector, Kmr | Vick et al. (2011) |

| pmtrB | mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrE | mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This work |

| pdmsF | dmsF and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This work |

| pSO4359 | SO4359 and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrC and 53 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrF and 35 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrC and 53 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/dmsE | dmsE and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrC and 53 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/dmsE | dmsE and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/dmsE | dmsE and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/SO4360 | SO4360 and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrC and 53 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/SO4360 | SO4360 and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/SO4360 | SO4360 and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/mtrB/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence, mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrB/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence, mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrB/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrC and 53 bp upstream, mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrB/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrC and 53 bp upstream, mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrB/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence, mtrB and 43 bp upstream in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pomcA/mtrE/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, omcA and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence, mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrE/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrF and 53 bp mtrC upstream sequence, mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrE/mtrA | mtrA and 38 bp upstream, mtrC and 53 bp upstream, mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrC/mtrE/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrC and 53 bp upstream, mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

| pmtrF/mtrE/mtrD | mtrD and 38 bp mtrA upstream sequence, mtrF and 53 bpmtrC upstream sequence, mtrE and 43 bp mtrB upstream sequence in pBBR-BB, Kmr | This work |

Mutant construction

Deletions in the MR-1 genome were made as previously described (Hau et al., 2008; Coursolle et al., 2010). All gene deletions were deigned to be in-frame to minimize polar effects on downstream genes. Briefly, up and downstream fragments flanking the gene targeted for deletion were ligated into the suicide vector pSMV3 and transferred into WM3064. After allowing the plasmid-containing WM3064 strain to conjugate with the parent MR-1 strain, single recombinants were obtained by plating this mixture to LB + kanamycin plates. Double recombinants were obtained by plating single recombinants onto LB + 5% sucrose plates and mutants screened by colony PCR from these plates. All mutants were then verified to be kanamycin sensitive and all permanent stocks retested by PCR using primers flanking the targeted gene. Primers used for deletions and complementation can be visualized in Table A1 in Appendix.

Complementation

Single and multiple genes were complemented into various MR-1 strains using the pBBR/pUC-BioBrick system, pBBR-BB (Vick et al., 2011). Due to prior expression issues (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010), 38 base pairs of upstream mtrA sequence, 53 base pairs of upstream mtrC sequence, and 43 base pairs of upstream mtrB sequence were included before mtrA, mtrC, and mtrB paralogs, respectively to normalize expression. Each gene is driven by an individual lac promoter (Vick et al., 2011). Briefly, each gene was cloned into the pUC-BB vector, digested out, and ligated into pBBR-BB sequentially. Genes cloned in top BBR-BB were verified using PCR, restriction analysis (using XbaI and SpeI), and sequencing. Primers used for complementation can be seen in Table A1 in Appendix. When appropriate, heme stains were performed to visualize the presence of c-type cytochromes (see below).

Iron(III) citrate reduction

Iron(III) citrate was used to test the Mtr-pathway constructs due to the speed and dynamic range of the assay compared to Iron(III) oxide (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). MR-1 strains were grown in LB overnight and normalized to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.35 in SBM. Thirty microliters of these cultures was then used to inoculate 270 μL of SBM containing 20 mM lactate and 10 mM iron(III) citrate in a 96-well plate. Iron(II) formation was monitored over time as previously described (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010) using ferrozine (Stookey, 1970). Between time points 96-well plates were placed in an adapted anaerobic Petri dish holder and flushed with nitrogen for 15 min. Reduction rates were calculated over the linear portion of each curve and normalized to the amount of protein in each well. Protein concentrations were calculated using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturers protocol.

Heme staining

Cultures were grown overnight in SBM containing 20 mM lactate and 10 mM iron(III) citrate and sonicated to lyse cells. Supernatants were separated and tested for protein concentration. Ten micrograms protein was loaded into each well of a 4–12% Bis–Tris SDS PAGE protein gel (Invitrogen) and run at 110 V for 120 min. The gels were then stained in a 3:7 6.3 mM tert-methylbenzadine (TMBZ) in methanol: 0.25 M sodium acetate for 2 h. The gels were visualized upon the addition of 30 mM hydrogen peroxide for 15 min.

Results

Functionality of MtrB paralogs

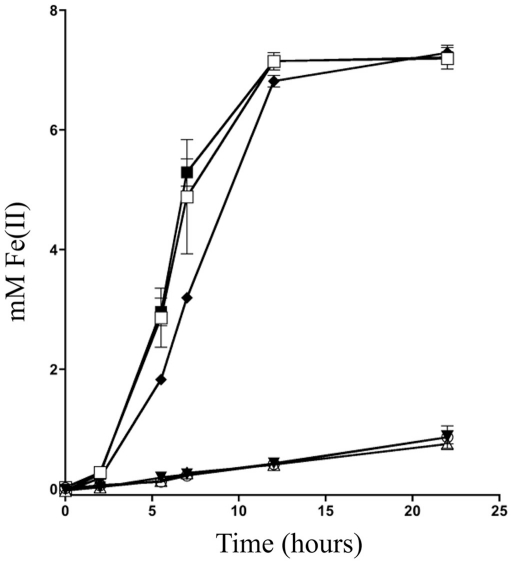

To determine what mtrB paralogs are able to functionally replace MtrB, we placed mtrB, mtrE, dmsF, and SO4359 under control of a constitutive promoter on the expression vector pBBR1MCS-2 (Kovach et al., 1995) and tested their ability to complement an mtrB deletion strain for iron(III) citrate reduction activity. Iron(III) citrate was used as a proxy for all Mtr activity due to its fast reduction rate and electron shuttle independent reduction mechanism (Von Canstein et al., 2008; Coursolle et al., 2010). Both MtrB and MtrE restored activity to levels slightly above wild type with empty vector (Figure 2), implying that MtrE can functionally replace MtrB. Neither expression of DmsF or SO4359 in ΔmtrB raised iron(III) citrate reduction levels significantly above an empty vector control (Figure 2), indicating that these paralogs are not functional in metal reduction modules. Knowing that only two mtrB paralogs have functionality during iron(III) citrate reduction limits the number of total possible functional modules to 24 allowing for less downstream plasmid construction.

Figure 2.

Iron(III) citrate reduction using various mtrB paralogs. The reduction of ferric citrate over time was measured for ∆mtrB complemented with (□) mtrB, (Δ) dmsF, (▼) SO4359, (■) mtrE, and (○) empty vector were compared to (♦) MR-1 with empty vector.

MtrA/MtrC paired interactions

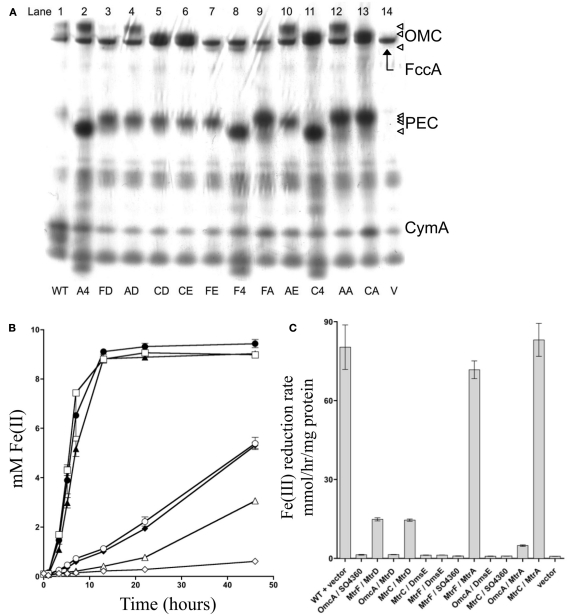

Previous studies have demonstrated that MtrD and DmsE can functionally replace MtrA (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010), while MtrF and to a smaller extent OmcA can functionally replace MtrC (Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). MtrC and MtrA interact through the pore in the OM created by the β-barrel MtrB protein (Hartshorne et al., 2009), yet remains unknown which OMC/PEC paralog interactions are functional in vivo. To test which pairs can functionally interact, we constructed a strain of S. oneidensis missing all identified OMCs and PECs (mtrA, mtrD, dmsE, SO4360, mtrC, mtrF, omcA, and cctA). After all genes were individually removed, the recA gene was deleted from the strain to nullify recombination between lac promoters driving expression of OMCs and PECs tested (see below). The resultant strain was named ΔMtr (Table 2). Functional characterization of PEC and OMC pairs (12 total combinations) were cloned into the pBBR-BB. Each of the complemented strains was verified via heme staining (Thomas et al., 1976) to express PEC and OMC paralogs. Figure 3A demonstrates that each of the 12 strains expressed both a PEC and an OMC with covalently attached heme groups. Interestingly, MtrA and SO4360 appear to be expressed at higher levels than MtrD and DmsE, even though the same promoter and ribosome-binding site drive expression of all four PECs. In the same manner, MtrF appears to be present at lower levels in complemented strains though the genes for all three OMCs share the same promoter, RBS, and 35 base pair upstream sequence. The 12 complemented strains were then evaluated for their ability to reduce iron(III) citrate. Overall, ΔMtr strains expressing MtrC/MtrA, MtrC/MtrD, MtrF/MtrA, MtrF/MtrD, and OmcA/MtrA were able to reduce iron(III) citrate at a rate significantly above an empty vector control (Figures 3B,C), while other PEC/OMC pairs did not. ΔMtr strains expressing MtrC/MtrA and MtrF/MtrA reduced iron(III) citrate at rates comparable to MR-1, while the other three functional combinations (MtrC/MtrD, MtrF/MtrD, and OmcA/MtrA) resulted a rate significantly lower than wild type. Though we demonstrated activity of OMC/PEC pairs, we could not yet determine which MtrB homolog was facilitating interactions between the c-type cytochromes.

Figure 3.

mtrC/mtrA paralog interactions. (A) Heme stain for ΔMtr strains complemented various paralogs. FccA, CymA, and CctA are labeled based on analysis of deletion mutant strains lacking the respective gene (data not shown). Triangles on right represent OmcA, MtrC, and MtrF for outer-membrane cytochromes (OMC) and MtrA, MtrD, DmsE, and 4360 for periplasmic electron carriers (PEC). MR-1 wildtype control (lane 1), OmcA/SO4360 (lane 2), MtrF/MtrD (lane 3), OmcA/MtrD (lane 4), MtrC/MtrD (lane 5), MtrC/DmsE (lane 6), MtrF/DmsE (lane 7), MtrF/SO4360 (lane 8), MtrF/MtrA (lane 9), OmcA/DmsE (lane 10), MtrC/SO4360 (lane 11), OmcA/MtrA (lane 12), MtrC/MtrA (lane 13), and empty pBBR-BB (lane 14). (B) Ferric citrate reduction for ∆Mtr strains complemented with vectors encoding mtrF/mtrD (♦), mtrC/mtrD (○), mtrF/mtrA (▲), omcA/mtrA (Δ), mtrC/mtrA (□), and empty pBBR-BB (◊). MR-1 with empty pBBR-BB (●) is included for reference. All not shown PEC/OMC combinations did not reduce ferric citrate significantly faster than the ΔMtr+ empty vector control and for the sake of brevity are not depicted. (C) Rates of Fe(III) citrate reduction for ΔMtr strain complemented with the indicated proteins. Rates are reported in millimolar per hour per microgram protein.

MtrB paralogs

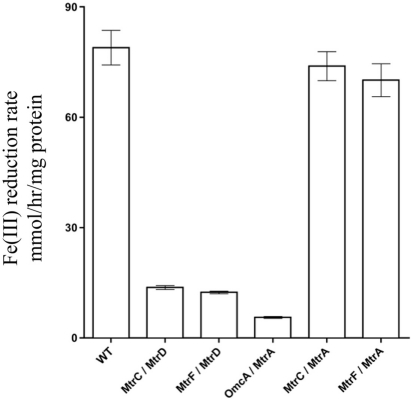

Identification of all functional PEC/OMC iron(III) citrate respiratory complexes allowed for evaluation of which mtrB paralog(s) can facilitate PEC/OMC interactions. Since only MtrB and MtrE could complement ΔmtrB (Figure 2), only these two β-barrel proteins were analyzed. To test the involvement of MtrB and MtrE in facilitating electron exchange between PECs and OMCs mtrB and mtrE were deleted from the recA+ ΔMtr parent strain to make ΔMtr/mtrB and ΔMtr/mtrE, respectively. Once constructed, recA was deleted to ensure plasmid stability for testing complementation constructs. When the five functional OMC/PEC paralog combinations were introduced into ΔMtr/mtrE, which still expresses mtrB, there was no significant difference between when the same combinations were complemented into ΔMtr (Figure 4). When the same mtrA/mtrC paralog combinations were complemented into ΔMtr/mtrB, all strains reduced iron(III) citrate at rates comparable to the empty vector control (data not shown). We can therefore conclude that MtrE is not contributing to iron(III) citrate reduction under these conditions and that MtrB is required for the activities observed in Figure 4. However, since the relative expression levels of mtrB and mtrE in these backgrounds are not known, the ability of MtrE to function with OMC/PEC paralog pairs could not be ruled out. To normalize expression levels of MtrE and MtrB, we generated pBBR-BB constructs encoding all three components: PEC, β-barrel, and OMC.

Figure 4.

Iron(III) citrate reduction by ΔMtr/ΔmtrE complemented strains. Iron(III) citrate reduction rate ofΔMtr/ΔmtrE complemented strains. Rates are reported in millimolar per hour per microgram protein.

Functional Mtr modules

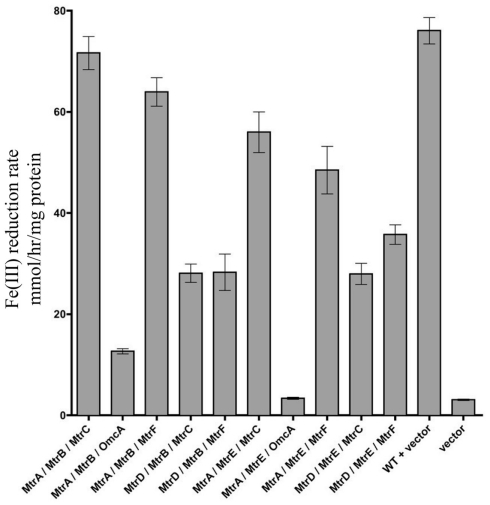

To determine which combinations of mtrC/mtrA/mtrB paralogs could form functional iron-reducing complexes, a series of paralog modules were reconstructed. Ten mtrCAB paralog modules were chosen because all OMC/PEC paralog combinations capable of forming functional complexes had been identified (Figure 3C), and only MtrB and MtrE appear to complement strains lacking mtrB (Figure 2). To analyze the functionality of complexes, both mtrB and mtrE were deleted from the ΔMtr parent strain (recA+) and plasmids containing each of the 10 complexes to be tested were placed in the resulting strain (ΔMtr/mtrB/mtrE) after removal of recA. We found that each of these combinations resulted in strains able to reduce iron(III) citrate at variable rates (Figure 5). The lowest rates were observed for both constructs producing OmcA, indicating that this protein has very little activity against iron(III) citrate, agreeing with previous observations (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010; Coursolle et al., 2010). As expected, MtrA/MtrB/MtrC had the highest activity followed by MtrA/MtrB/MtrF. The results are in agreement with recent data demonstrating that MtrF and MtrC share similar activity (Bucking et al., 2010; Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010) and likely a similar structure (Clarke et al., 2011). All complemented strains expressing MtrA had higher reduction rates when co-expressed with MtrB than MtrE. Likewise, complemented strains expressing MtrD reduced iron(III) citrate at the same rate or faster when co-expressed with MtrE. Overall, we observed that all tested MtrA/MtrB/MtrC paralog combinations were able to reduce iron(III) citrate with the exception of MtrA/MtrE/OmcA, suggesting that MtrE is unable to facilitate interaction between MtrA and OmcA.

Figure 5.

Iron(III) citrate reduction by all possible functional Mtr modules. Iron(III) citrate reduction rate ofΔMtr/ΔmtrB/ΔmtrE complemented strains. Rates are reported in millimolar per hour per microgram protein.

Discussion

We have reconstructed and identified components from the inventory of mtrA, mtrB, and mtrC paralogs found in the genome of S. oneidensis that function together to conduct electrons to soluble iron(III) citrate. Together, the three protein components, a PEC, β-barrel, and OMC form an electron conduit to the outside of the cell (Figure 1) where soluble and insoluble substrates are reduced by S. oneidensis (Coursolle and Gralnick, 2010). The apparent redundancy of these components is unusual, however the degree of variation in the utility of these components in reducing iron(III) citrate and occurrence in other sequenced Shewanella strains (Fredrickson et al., 2008) suggests these paralogs have divergent, but slightly overlapping function. The overlapping functionality may be an artifact of sharing common ancestry or a biochemical constraint on the system from either the source of electrons (the menaquinone pool and CymA) or the destination of the electrons (e.g., an external respiratory substrate) or both. With the exception of mtrD up-regulation during oxygen-dependent autoaggregation when exposed to high calcium concentrations (McLean et al., 2008), the conditions under which the mtrDEF and SO4359-62 gene clusters are expressed in MR-1 have not yet been identified, so the specific function of the proteins encoded by these genes remains unknown. The conservation of mtrDEF and SO4359-62 in sequenced Shewanella that have copies of mtrABC and dmsABEF implies that these genes have distinct functions. Moreover, the fact that SO4360 always clusters with dmsAB homologs and mtrD with mtrBC homologs implies that SO4359-62 may share overlapping functionality with DMSO reductases and mtrDEF with metal reductases. E. coli’s DmsAB have shown in vitro reduction activity with N-oxides, sulfoxides, hydroxylamine, and chlorate, making these likely substrates for the SO4359-62 module (Bilous et al., 1988).

One unexplained phenomenon is the existence of several parologous pathways that use CymA as the link to CM quinone pools. In fact, all known substrates respired by MR-1, with the exception of oxygen, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), thiosulfate, sulfite, and sulfur require the use of CymA and menaquinone as electron mediators (Myers and Myers, 1997; Schwalb et al., 2003; Shirodkar et al., 2011). In the genome of MR-1, TMAO, sulfite, and elemental sulfur reductases all exist in operons with putative quinone-oxidoreductases, explaining why CymA and in some cases menaquinones are not required for the reduction of these substrates (Kwan and Barrett, 1983; Wissenbach et al., 1992; Gon et al., 2002; Shirodkar et al., 2011). Many of the anaerobic CymA-utilizing pathways present in MR-1 have homologs in other organisms such as E. coli. For instance, DmsAB, FrdAB, NrfABC, and NapAB all exist in other organisms and utilize their own quinone-oxidoreductases: DmsC, FrdDC, NrfD, and NapC respectively (Berks et al., 1995; Potter et al., 2001). MR-1 has evolved to integrate the use of these terminal reductases with a single quinone-oxidoreductase, CymA. By using CymA as an electron bottleneck, MR-1 has introduced the ability to regulate multiple anaerobic respiratory pathways with the regulation of a single protein. There is evidence that many anaerobic respiratory pathways are turned on in the absence of oxygen, regardless of electron acceptor availability (Beliaev et al., 2002). The benefit Shewanella would experience by turning on several respiratory pathways at once is rapid elimination of electrons from the interior of the cell for redox carrier regeneration to allow energy-generating substrate-level phosphorylation to proceed regardless of which electron acceptor is available (Hunt et al., 2010). Many Shewanella species have been isolated at aerobic/anaerobic interfaces in aquatic systems (Nealson and Saffarini, 1994), where they must frequently switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration. To regulate respiratory pathways individually may prove energetically inefficient, especially if different acceptors are present simultaneously. Therefore, it may be more favorable for MR-1 to up-regulate several anaerobic respiratory pathways at once, especially when oxygen availability may fluctuate often.

One interesting observation made in this study is that neither DmsF nor SO4359 were able to facilitate interactions between PECs and OMCs for the purpose of iron(III) citrate reduction. Both dmsF and SO4359 are located in gene clusters containing predicted homologs to the DMSO reductase subunits dmsAB. The putative β-barrel integral OM proteins DmsF and SO4359 each likely interact with PEC proteins encoded in their respective gene clusters. The β-barrel paralogs are similar in predicted size (MtrB – 697aa, MtrE – 712aa, DmsF – 662aa, SO4359 – 656aa), and therefore could have a similar number of transmembrane domains. Consistent with our functional studies, MtrB and MtrF are closer in size when compared to DmsF and SO4359. However, instead of a multiheme c-type cytochrome as the terminal reductase, there are two terminal reductase subunits: DmsB, which contains a 4Fe–4S cluster and DmsA, which contains a molybdopterin cofactor (Weiner et al., 1992). These DmsAB complexes may interface with the MtrB paralogs DmsF and SO4359 differently than with an OMC. Hence, it is more likely that DmsF and SO4359 would be able to functionally replace each other, since the terminal branch of their respiratory chains are also paralogs.

In this study we have identified nine different MtrA/MtrB/MtrC paralog modules of the Mtr respiratory pathway that could be used to move electrons from the CM (CymA) to the outside of the cell (OMC). One could imagine a heterologous expression system where proteins with different redox potentials could be integrated with core Mtr-pathway components. However, though many pathways exist to traffic electrons to the cell surface, the purpose of two of the pathways remain unknown. Their presence in the MR-1 and other Shewanella genomes is consistent with their functionality/utility for these bacteria in the environment. Understanding the role of these pathways may help explain the global aquatic presence of Shewanella and could lead to new biotechnological applications of these diverse bacteria.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Gralnick and Bond Labs for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the Office of Naval Research (award N000140810166) to Jeffrey A. Gralnick.

Appendix

Table A1.

Primers and restriction sites used for cloning and subsequent generation of mutant and complemented strains.

| Primer | Restriction site | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| DELETIONa | ||

| OmcA up 1 | Spe1 | NNACTAGTCAGGTCTCACAGTACCCGCA |

| MtrB up 1 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCCGTTCAACCTCTCGCGCTTA |

| MtrB up 2 | BamHI | NNNGGATCCCTTTACAGCTCCATGCGGAT |

| MtrB down 1 | BamHI | NNNGGATCCATGGCATTTGGAACGTCGTAGG |

| MtrB down 2 | SpeI | NNACTAGTTCTGGACGTGGCGGCTTATC |

| MtrE up 1 | SacI | NNNGAGCTCGCAGTAAATCGTAAATACCGG |

| MtrE up 2 | BamHI | NNNGGATCCGTCGATATATTCACTATTTGC |

| MtrE down 1 | BamHI | NNNGGATCCAGGTTTGACCTTAAGCTACC |

| MtrE down 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCTATTACAAGTGTCGATCGAGA |

| COMPLEMENTATIONb | ||

| OmcA 1 | BglII | NNNAGATCTGTTGGCGCTAGAGCATAGCGGTTAAGCAAT |

| GCCAAACCTATGCAGGGAAAAAAATGATGAAACGGTTCAATTTCA | ||

| OmcA 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCAACCACAAGGGAAAAACAAA |

| MtrC 1 | BglII | NNNAGATCTGTTGGCGCTAGAGCATAG |

| MtrC 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCTAATAGGCTTCCCAATTTGT |

| MtrF 1 | BglII | NNNAGATCTGTTGGCGCTAGAGCATAGCGGTTAAGCAA |

| TGCCAAACCTATGCAGGGAAAAAAATGAATAAGTTTGCAAGCT | ||

| MtrF 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCTTGGGCCTGCATCATCGAGTTAG |

| MtrB 1 | BglII | NNNAGATCTCCATCCATCTGGCAAGCTAT |

| MtrB 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCGGGCTTTTGAGCATATGAGG |

| MtrE 1 | BglII | NNNAGATCTCCATCCATCTGGCAAGCTATTACAGCGC |

| TAAGGAGACGAGAAAATGCAAATAGTGAATATATCG | ||

| MtrE 2 | NotI | NNNNNNNNNNGCGGCCGCGTGCCTAAGTTACATTTGGTAG |

| CTTAA | ||

References

- Baron D., Labelle E., Coursolle D., Gralnick J. A., Bond D. R. (2009). Electrochemical measurement of electron transfer kinetics by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28865–28873 10.1074/jbc.M109.043455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beliaev A. S., Saffarini D. A. (1998). Shewanella putrefaciens mtrB encodes an outer membrane protein required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. J. Bacteriol. 180, 6292–6297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beliaev A. S., Thompson D. K., Khare T., Lim H., Brandt C. C., Li G., Murray A. E., Heidelberg J. F., Giometti C. S., Yates J., III, Nealson K. H., Tiedje J. M., Zhoui J. (2002). Gene and protein expression profiles of Shewanella oneidensis during anaerobic growth with different electron acceptors. OMICS 6, 39–60 10.1089/15362310252780834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berks B. C., Ferguson S. J., Moir J. W., Richardson D. J. (1995). Enzymes and associated electron transport systems that catalyse the respiratory reduction of nitrogen oxides and oxyanions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1232, 97–173 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilous P. T., Cole S. T., Anderson W. F., Weiner J. H. (1988). Nucleotide sequence of the dmsABC operon encoding the anaerobic dimethyl sulphoxide reductase of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2, 785–795 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucking C., Popp F., Kerzenmacher S., Gescher J. (2010). Involvement and specificity of Shewanella oneidensis outer membrane cytochromes in the reduction of soluble and solid-phase terminal electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 306, 144–151 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01949.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke T. A., Edwards M. J., Gates A. J., Hall A., White G. F., Bradley J., Reardon C. L., Shi L., Beliaev A. S., Marshall M. J., Wang Z., Watmough N. J., Fredrickson J. K., Zachara J. M., Butt J. N., Richardson D. J. (2011). Structure of a bacterial cell surface decaheme electron conduit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9384–9389 10.1073/pnas.1017200108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursolle D., Baron D. B., Bond D. R., Gralnick J. A. (2010). The Mtr respiratory pathway is essential for reducing flavins and electrodes in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 192, 467–474 10.1128/JB.00925-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursolle D., Gralnick J. A. (2010). Modularity of the Mtr respiratory pathway of Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 995–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firer-Sherwood M., Pulcu G. S., Elliott S. J. (2008). Electrochemical interrogations of the Mtr cytochromes from Shewanella: opening a potential window. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 13, 849–854 10.1007/s00775-008-0398-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firer-Sherwood M. A., Ando N., Drennan C. L., Elliott S. J. (2011). Solution-based structural analysis of the decaheme cytochrome, MtrA, by small-angle X-ray scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 11208–11214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J. K., Romine M. F., Beliaev A. S., Auchtung J. M., Driscoll M. E., Gardner T. S., Nealson K. H., Osterman A. L., Pinchuk G., Reed J. L., Rodionov D. A., Rodrigues J. L., Saffarini D. A., Serres M. H., Spormann A. M., Zhulin I. B., Tiedje J. M. (2008). Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 592–603 10.1038/nrmicro1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescher J. S., Cordova C. D., Spormann A. M. (2008). Dissimilatory iron reduction in Escherichia coli: identification of CymA of Shewanella oneidensis and NapC of E. coli as ferric reductases. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 706–719 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gon S., Patte J. C., Dos Santos J. P., Mejean V. (2002). Reconstitution of the trimethylamine oxide reductase regulatory elements of Shewanella oneidensis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1262–1269 10.1128/JB.184.5.1262-1269.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnick J. A., Newman D. K. (2007). Extracellular respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1–11 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05778.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnick J. A., Vali H., Lies D. P., Newman D. K. (2006). Extracellular respiration of dimethyl sulfoxide by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4669–4674 10.1073/pnas.0505959103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne R. S., Reardon C. L., Ross D., Nuester J., Clarke T. A., Gates A. J., Mills P. C., Fredrickson J. K., Zachara J. M., Shi L., Beliaev A. S., Marshall M. J., Tien M., Brantley S., Butt J. N., Richardson D. J. (2009). Characterization of an electron conduit between bacteria and the extracellular environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22169–22174 10.1073/pnas.0900086106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hau H. H., Gilbert A., Coursolle D., Gralnick J. A. (2008). Mechanism and consequences of anaerobic respiration of cobalt by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6880–6886 10.1128/AEM.00840-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt K. A., Flynn J. M., Naranjo B., Shikhare I. D., Gralnick J. A. (2010). Substrate-level phosphorylation is the primary source of energy conservation during anaerobic respiration of Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3345–3351 10.1128/JB.00090-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop R. M., II, Peterson K. M. (1995). Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166, 175–176 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan H. S., Barrett E. L. (1983). Roles for menaquinone and the two trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) reductases in TMAO respiration in Salmonella typhimurium: Mu d(Apr lac) insertion mutations in men and tor. J. Bacteriol. 155, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J. R., Lovley D. R., MacAskie L. E. (2003). Biotechnological application of metal-reducing microorganisms. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 53, 85–128 10.1016/S0065-2164(03)53003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R. (2008). The microbe electric: conversion of organic matter to electricity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 564–571 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili E., Baron D. B., Shikhare I. D., Coursolle D., Gralnick J. A., Bond D. R. (2008). Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3968–3973 10.1073/pnas.0710525105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J. S., Pinchuk G. E., Geydebrekht O. V., Bilskis C. L., Zakrajsek B. A., Hill E. A., Saffarini D. A., Romine M. F., Gorby Y. A., Fredrickson J. K., Beliaev A. S. (2008). Oxygen-dependent autoaggregation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1861–1876 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. R., Myers J. M. (1997). Cloning and sequence of cymA, a gene encoding a tetraheme cytochrome c required for reduction of iron(III), fumarate, and nitrate by Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 179, 1143–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. R., Nealson K. H. (1988). Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240, 1319–1321 10.1126/science.240.4857.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H., Saffarini D. (1994). Iron and manganese in anaerobic respiration: environmental significance, physiology, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48, 311–343 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts K. E., Dobbin P. S., Reyes-Ramirez F., Thomson A. J., Richardson D. J., Seward H. E. (2003). Characterization of the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 decaheme cytochrome MtrA: expression in Escherichia coli confers the ability to reduce soluble Fe(III) chelates. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27758–27765 10.1074/jbc.M302582200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter L., Angove H., Richardson D., Cole J. (2001). Nitrate reduction in the periplasm of gram-negative bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 45, 51–112 10.1016/S0065-2911(01)45002-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D. E., Brantley S. L., Tien M. (2009). Kinetic characterization of OmcA and MtrC, terminal reductases involved in respiratory electron transfer for dissimilatory iron reduction in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 5218–5226 10.1128/AEM.00544-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltikov C. W., Newman D. K. (2003). Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10983–10988 10.1073/pnas.1834303100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalb C., Chapman S. K., Reid G. A. (2003). The tetraheme cytochrome CymA is required for anaerobic respiration with dimethyl sulfoxide and nitrite in Shewanella oneidensis. Biochemistry 42, 9491–9497 10.1021/bi034456f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Squier T. C., Zachara J. M., Fredrickson J. K. (2007). Respiration of metal (hydr)oxides by Shewanella and Geobacter: a key role for multiheme c-type cytochromes. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 12–20 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05783.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirodkar S., Reed S., Romine M., Saffarini D. (2011). The octahaem SirA catalyses dissimilatory sulfite reduction in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 108–115 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stookey L. L. (1970). Ferrozine – a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 42, 779–781 10.1021/ac60289a016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. E., Ryan D., Levin W. (1976). An improved staining procedure for the detection of the peroxidase activity of cytochrome P-450 on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 75, 168–176 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90067-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswaran K., Moser D. P., Dollhopf M. E., Lies D. P., Saffarini D. A., MacGregor B. J., Ringelberg D. B., White D. C., Nishijima M., Sano H., Burghardt J., Stackebrandt E., Nealson K. H. (1999). Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Shewanella and description of Shewanella oneidensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt 2), 705–724 10.1099/00207713-49-2-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick J. E., Johnson E. T., Choudhary S., Bloch S. E., Lopez-Gallego F., Tikh I. B., Wawrzyn G. T., Schmidt-Dannert C. (2011). Optimized compatible set of BioBrick vectors for metabolic pathway engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92, 1275–1286 10.1007/s00253-011-3633-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Canstein H., Ogawa J., Shimizu S., Lloyd J. R. (2008). Secretion of flavins by Shewanella species and their role in extracellular electron transfer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 615–623 10.1128/AEM.01387-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J. D., Krumholz L. R. (2006). Uranium reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 149–166 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Liu C., Wang X., Marshall M. J., Zachara J. M., Rosso K. M., Dupuis M., Fredrickson J. K., Heald S., Shi L. (2008). Kinetics of reduction of Fe(III) complexes by outer membrane cytochromes MtrC and OmcA of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6746–6755 10.1128/AEM.02800-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. H., Rothery R. A., Sambasivarao D., Trieber C. A. (1992). Molecular analysis of dimethylsulfoxide reductase: a complex iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1102, 1–18 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90059-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton N. S., Rosso K. M., Hochella M. F., Jr. (2007). Mechanisms of electron transfer in two decaheme cytochromes from a metal-reducing bacterium. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 12857–12864 10.1021/jp0718698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissenbach U., Ternes D., Unden G. (1992). An Escherichia coli mutant containing only demethylmenaquinone, but no menaquinone: effects on fumarate, dimethylsulfoxide, trimethylamine N-oxide and nitrate respiration. Arch. Microbiol. 158, 68–73 10.1007/BF00249068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Shi L., Chen B., Mayer M. U., Lower B. H., Londer Y., Bose S., Hochella M. F., Fredrickson J. K., Squier T. C. (2006). High-affinity binding and direct electron transfer to solid metals by the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 outer membrane c-type cytochrome OmcA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13978–13979 10.1021/ja063526d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]