Abstract

To develop an effective vaccine against eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), we engineered a recombinant EEE virus (EEEV) that was attenuated and capable of replicating only in vertebrate cells, an important safety feature for live vaccines against mosquito-borne viruses. The subgenomic promoter was inactivated with 13 synonymous mutations and expression of the EEEV structural proteins was placed under the control of an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) derived from encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV). We tested this vaccine candidate for virulence, viremia and efficacy in the murine model. A single subcutaneous immunization with 104 infectious units protected 100% of mice against intraperitoneal challenge with a highly virulent North American EEEV strain. None of the mice developed any signs of disease or viremia after immunization or following challenge. Our findings suggest that the IRES-based attenuation approach can be used to develop a safe and effective vaccine against EEE and other alphaviral diseases.

Keywords: alphavirus, RNA virus, attenuation, vaccine, eastern equine encephalitis virus

1. Introduction

Viruses in the genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae, have positive strand RNA genomes and cause a spectrum of diseases that includes fever, rash, arthritis, meningitis and encephalitis. Most alphaviruses are mosquito-borne, and transmitted in nature among zoonotic vertebrate reservoir hosts, including birds, primates and rodents. Based on their cross reactivity, several antigenic complexes including the EEE, Venezuelan (VEE) and western equine encephalitis (WEE) complexes comprise the Alphavirus genus [1, 2]. EEEV is considered the most deadly of all the alphaviruses due to the high case fatality rates associated with infections, reaching as high as 90% in horses. In humans, the estimated case fatality rate approaches 80% and many survivors exhibit crippling sequelae such as mental retardation, convulsions, and paralysis that require life-long institutionalized care [3, 4].

Based on antigenic and genetic analyses, EEEV is classified into 4 subtypes: subtype 1 includes strains from North America (NA), whereas the remaining 3 are found in Central and South America (SA) [5, 6]. In general, EEEV strains from SA appear to be less virulent for humans than NA strains [7]. The former can occasionally cause disease and death in horses, but human infections are rarely recognized. In contrast, NA strains are genetically conserved, uniformly virulent and cause severe encephalitis in both humans and equids [8, 9, 10]. However, in mice, both NA and SA strains of EEEV are highly virulent and cause mortality rates as high as 70 to 90% following subcutaneous, intraperitoneal or intramuscular infection [11, 12]. In outbred laboratory mice, EEEV produces neurologic disease that resembles that following human and equine infections. Virus has been detected in the brain as early as day 1 post-infection (PI), and signs of disease are evident as early as days 3-4. Clinical signs of murine disease include ruffled hair, anorexia, vomiting, lethargy, posterior limb paralysis, convulsions, and coma. Histopathological studies reveal extensive involvement of the brain, including neuronal degeneration, cellular infiltration, and perivascular cuffing, similar to the pathological changes of the central nervous system that are described in naturally infected humans [11]. Immune protection against alphaviruses has been attributed mainly to the humoral response, with titers of neutralizing antibodies directly proportional to the level of protection against disease upon challenge [13, 14, 15, 16].

Despite over 65 years of research there is no licensed human vaccine or effective antiviral treatment available for human EEE, and control depends on mosquito abatement measures and avoidance of exposure to mosquito bites. Several live-attenuated candidate vaccines derived from the wild-type, virulent EEEV were assessed for their safety and efficacy in mice (17, 18) but have not been developed further. A formalin-inactivated vaccine prepared from a wild-type NA strain of EEEV [19] under Investigational New Drug (IND) status is currently available only for researchers and military personnel [20], and a similar inactivated vaccine is sold for equids and other domesticated animals [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture licensed a three-component vaccine composed of inactivated VEE, EEE and WEE viruses, for use in equids [27, 28]. However, all of these inactivated vaccines suffer from poor immunogenicity and from the risk of residual live virus in the vaccine lot (29).

In addition to its importance as a natural pathogen of humans and domesticated animals, EEEV is a potent biological weapon [30], adding further urgency to the need for an effective vaccine. Therefore, we sought to develop an attenuated EEEV strain that would induce rapid, robust and long-lived immunity after a single vaccination. Earlier, Wang et. al. developed two chimeric alphavirus strains (SIN/EEEV), both of which replicate efficiently in mammalian and mosquito cell cultures without any adaptation (31). These vaccines were shown to be highly attenuated, immunogenic and efficacious against EEEV challenge in murine testing. Another chimeric alphavirus, which is derived from a cDNA clone encoding the western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV) nonstructural polyprotein and the EEEV structural polyprotein protects mice against EEEV but not against WEEV challenge (32). Because the recombinant nature of these chimeras is believed to confer the attenuation phenotype, rather than point mutations that are subject to high rates of reversion, these chimeric viruses appear to be stably attenuated [33]. However, another safety concern for live, genetically engineered vaccines against arboviral diseases is that recombinant viruses might evolve in unforeseen and unexpected ways if they inadvertently underwent vector-borne circulation in the nature. The isolation of the VEEV vaccine strain, TC-83, from naturally infected mosquitoes collected in Louisiana during a 1971 Texas epidemic demonstrated the risk of transmission of attenuated alphaviruses [34], and experimental infections of the chimeric EEE vaccine strains demonstrated some residual mosquito infectivity [35].

To eliminate potential mosquito infectivity of live alphavirus vaccine strains, the findings of Finkelstein et al, that insect cells do not support efficient internal translation initiation from an encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) [36], were exploited in another vaccine design [37]. The VEEV vaccine strain TC-83 was modified in cDNA clone form to replace the subgenomic promoter with EMCV IRES to drive expression of the structural protein genes from genomic RNA in mammalian cells. The resulting strain is incapable of infecting mosquitoes, and is also further attenuated for mice. Beginning with a wild-type backbone of chikungunya virus, this IRES approach produced a vaccine candidate that appears to have an optimal balance of immunogenicity and attenuation, combined with a lack of mosquito infectivity [38]. In addition to EMCV IRES, attenuation and elimination of mosquito infectivity was also dependent on inactivated subgenomic promoter as previously reported by Volvoka et. al, and Plante et al. Northern blot analysis performed by both these groups confirmed that insertion of several synonymous point mutations efficiently inactivated the subgenomic promoter [37, 38].

Considering these promising results, we utilized the EMCV IRES approach to generate an attenuated, mosquito-incompetent EEEV vaccine candidate. This recombinant virus was evaluated in mice to assess attenuation, immunogenicity and protection against EEEV challenge, and was also tested for its ability to infect mosquito cells and mosquitoes in vivo. The strong attenuation and mosquito-incompetent phenotypes we measured further support the promise of this approach for alphavirus vaccine development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell lines

Baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) and Vero cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Bethesda, MD) and grown at 370C in Eagle’s minimal medium (MEM) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.005% gentamycin sulphate. The mosquito cell line C6/36, also from the ATCC, was maintained in MEM at 320C with 5% FBS and 10% tryptose phosphate broth.

2.2 Virus

Wild-type (WT) North American EEEV strain FL93-939 was used for the development of the recombinant construct and also for all challenge experiments in mice. This strain was isolated from a pool of Culiseta melanura mosquitoes collected in Florida during 1993, and was passaged once in Vero cells before cDNA clone construction. Virus stocks were prepared from baby hamster cell cultures electroporated with in vitro transcribed RNA, as described earlier [39].

2.3 Construction of recombinant plasmid

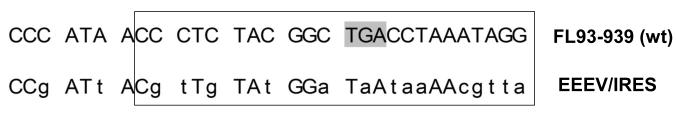

To develop an EEEV strain capable of replicating efficiently in vertebrate but not in mosquito cells, we made the expression of the EEEV structural proteins dependent on the EMCV IRES. Briefly, the IRES was PCR-amplified using specific primers from the plasmid TC-83/IRES [37] and joined with the 3′ terminus of the nsP4 gene and 5′ terminus of the capsid gene using standard fusion PCR techniques. Primers also contained a sequence with a cluster of 16 synonymous point mutations, which inactivated the subgenomic promoter (Fig.1). The resulting amplicon was cloned into the pM1FL93-939 plasmid using Cla I and Sfi I restriction sites to replace the natural subgenomic promoter and 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the subgenomic RNA to generate the pEEEV/IRES plasmid.

Figure 1.

Diagramatic representation of the mutated subgenomic promoter of EEEV/IRES. The position of the promoter is indicated by the open box and the mutations introduced to inactivate the subgenomic promoter in the vaccine candidate are shown in the lower case letters. The shaded codon in the wild type FL93-939 represents the stop codon.

2.4 RNA Transcription, transfection and production of infectious viruses

Once confirmed by sequencing, pEEEV/IRES plasmid DNA was purified with CsCl gradients and linearized by Not I restriction digestion. T7 RNA polymerase was then used in presence of cap analog (Ambion, Austin, TX) for RNA synthesis and the quality and yield of the RNA was determined by RNA gel electrophoresis under non-denaturing conditions. The RNA was electroporated into BHK-21 cells and the rescued virus, EEEV/IRES, was collected following the development of cytopathic effects (CPE). Virus titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells. For infectious center assays, 10-fold dilutions of the electroporated BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates containing confluent BHK cells. After a one-hour incubation at 37°C, cells were overlaid with 0.4% agarose in MEM, incubated for 2 days, and plaques counted after staining with 0.05% crystal violet in 30% methanol.

2.5 Viral Replication curves and cell culture passages

Replication kinetics of both parental strain FL93-939 and EEEV/IRES were compared in Vero as well as in C6/36 mosquito cells. Confluent monolayers grown in 12-well plates were infected in triplicate at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 PFU/cell at 37°C. After 1 hr of incubation, the plates were washed 3 times with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and 2 ml of MEM with 2% FBS was added to each well. At 12, 24, and 48 hrs post-infection, cell culture medium was collected and replaced with fresh medium. Virus titers in the harvested media were determined by standard plaque assay on Vero cells.

To study the replication competence of the vaccine candidate, mosquito cells grown to 80-95% confluence in T-25 flasks were infected either with EEEV/IRES or FL93-939 at a MOI of 1.0. After 48 hrs of incubation, the supernatant was used to infect fresh C6/36 cells in T-25 flasks (MOI 1.0 PFU/cell). Supernatants were collected after each passage for virus detection and cytopathic effects (CPE). Total RNA extracted from 100 μl of the mosquito homogenate supernatants using TRIzol LS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were also reverse transcribed (RT) using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) with random hexamer primers as per the manufacturer’s instructions. AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was then used to PCR-amplify EEEV specific fragment (primer sequences and protocol details available upon request).

To assess the genetic stability, EEEV/IRES was serial passaged in Vero cells at a MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell. Following 5 passages, total RNA was extracted from 100μl of supernatant as described above. Satandard RT-PCR techniques were used to obtain 1000-3500 nt-long fragments, which were then sequenced after agarose gel extraction.

2.6 Mouse Immunization and Challenge

Three- to 4-week-old male NIH Swiss mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. To monitor with greater sensitivity the potential clinical signs related to vaccination and challenge, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane inhalation one week before infection and implanted subcutaneously (SC) with a pre-programmed telemetry chip (IPTT-300; Bio Medical Data Systems, Inc., Seaford, DE) to measure body temperature. Cohorts of 20 mice were infected SC in the medial thigh either with PBS (Sham) or 104 PFU (in 100 μl) of EEEV/IRES. Body temperatures and weights were recorded daily without anesthesia and the animals were monitored daily for disease signs (ruffled fur, hunched posture, paralysis, etc.). Blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital sinus on day 1, 2 and 3 post immunization and virus titers were determined by plaque assay using Vero cells. On day 21 after vaccination, just before challenge, the mice were bled again for antibody assays using an 80% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT80) with Vero cells and standard methods [40].

Four weeks post-vaccination, mice were challenged intraperitoneally (IP) with 103 PFU (in 100 μl) of WT EEEV strain FL93-939. Again, body weights and temperature were recorded daily for 14 days and then weekly until the experiment was terminated 25 days after challenge. Three mice from the EEEV/IRES and sham-vaccinated groups were sacrificed on days 5, 6 and 7 post challenge and their brains harvested for virus titration. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.7 Mosquito infections in vivo

An Aedes albopictus colony established in 2003 from mosquitoes collected in Galveston, TX was used for these experiments. Adult female mosquitoes collected 3–4 days post-eclosion were injected intrathoracically (IT) with undiluted virus stock of either EEEV/IRES, the wt FL93-939 strain, or PBS. The mosquitoes were incubated for 7 days at 27°C with 10% sucrose provided ad libitum, then frozen and triturated individually in MEM containing 2% FBS and fungicide using a Tissuelyser II (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) for 2 min. Following centrifugation for 10 minutes at 10,000×G, the supernatant was plated on Vero cells monolayers on 24-well plates. Cells were observed for 5 days for cytopathic effects (CPE). Also, to confirm that the virus was unable to replicate in mosquitoes, RT-PCR was performed (as described earlier in section 2.5) in homogenate extracts of mosquito infected with EEEV/IRES and wild type FL93-939.

3. Results

3.1 Recombinant Virus

In the recombinant virus EEEV/IRES, the subgenomic promoter was inactivated by 16 synonymous point mutations, which prevented the reversion to an active SG RNA promoter. To promote synthesis of the EEEV structural proteins, the IRES sequence was cloned to replace the 5′ UTR in the subgenomic The infectivity of the recombinant viral EEEV/IRES RNA as determined by infectious center assay was 5×105 PFU/ 4 μg, which is comparable to that of other alphavirus cDNA clones (37, 41). A small and diffuse plaque morphology (data not shown) suggested that EEEV/IRES was attenuated in vitro.

3.2 Replication of chimeric viruses in cell culture

Parental and recombinant viruses recovered from BHK-21 cells after RNA electroporation were tested for replication in Vero (an approved mammalian cell line for vaccine production) (42) and C6/36 mosquito cells. The replication curves of wt strain FL93-939 and the recombinant EEEV/IRES in Vero cells are shown in Fig. 2. Both viruses replicated with similar efficacy (p>0.05), reaching maximum titers approaching 8 log10 PFU/ml, 24-48 hrs post infection, and then declining as cytopathic effects presumably reduced replication.

Figure 2.

Replication of FL93-939 and EEEV/IRES in Vero cells. Bars indicate standard deviations for triplicate infections.

To determine if EEEV/IRES could replicate in the mosquito cells, we infected C6/36 cells with a MOI of one PFU/cell; WT strain FL93-939 was included as a positive control. Plaque assays in the supernatant demonstrated that, although FL93-939 replicated efficiently in C6/36 cells (to titers ~ 108), no EEEV/IRES was detected in the supernatant of C6/36 cells at any of the time points assayed (12, 24, and 48 hrs. PI) and throughout the passages. The results were also confirmed by RT-PCR. Although, some EEEV/IRES was detected after first passage, we were unable to detect any virus thereafter (Fig. 3). The presence of the virus in the first passage supernatant could be attributed to the residual viruses, which were hard to wash off completely from the cells after infection.

Figure 3.

Detection of the EEEV/IRES by RT-PCR in mosquito cells (C6/36) after infection with EEEV/IRES and serial passages. Lane 1: FL93-939; Lanes 2-6: passage 1-5; Lane 7: molecular weight marker. Arrow indicates the expected amplicon size of ~750 bps

Sequence analysis of the EEEV/IRES genome after 5 serial passages in Vero cells (MOI = 0.1 PFU/ml) showed no nucleotide changes in the consensus sequence. Four minority nucleotide peaks were observed on the sequence electropherograms: these encoded D61→G, T72→K and Q194→R in the E2 glycoprotein and S47→F in the capsid protein.

3.3 Immunogenicity and protection against EEEV challenge

EEEV/IRES vaccination with 104 PFU induced neutralizing antibodies in all mice, with PRNT titers against NA EEEV in the range of 160-640 (mean = 352 ± 211).

None of the mice immunized at 4-5 weeks of age with EEEV/IRES showed a febrile response, and there were no significant differences in mean body weights or temperatures between EEEV/IRES-vaccinated versus sham-vaccinated (PBS) animals. Body temperatures remained within the normal range (36-38°C) (Fig. 4a) and weight gains continued until challenge on day 25 (Fig. 4b). Also, none of the vaccinated mice had detectable (limit of detection = 1.5 log10 PFU/ml) viremia during the first 3 days after immunization.

Figure 4.

Body temperature and body weight of NIH Swiss mice following vaccination with EEEV/IRES or PBS. (a) Body temperature post-vaccination (b) Body weight post-vaccination. Error bars indicate the standard deviations for triplicate experiments.

All vaccinated mice survived challenge with the virulent, wild type FL93-939. In contrast, all sham-vaccinated mice developed clinical signs of infection including ruffled hair, vomiting, lethargy, hunched posture and paralysis, and all died by day 6 post-challenge (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Survival of 4-5-week-old NIH Swiss mice following vaccination with EEEV/IRES or sham vaccination with PBS, followed by challenge with EEEV strain FL93-939

Post challenge, the mean body temperatures of EEEV/IRES-vaccinated mice remained ca. 37°C and none showed any clinical signs of disease. In contrast, the mean temperature of sham-vaccinated mice on day 4 post-challenge rose to 38°C (Fig. 6a), followed by death of all the mice by day 5. Vaccinated animals continued to gain weight after challenge and all survived for at least 25-days post challenge, when the experiment was terminated (Fig. 6b). In contrast, sham-vaccinated mice began losing weight on day 4 and lost an average of 11% of their weight on day 5 before death.

Figure 6.

Body temperature and weight of vaccinated (EEEV/IRES) or sham-vaccinated (PBS) NIH Swiss mice following intraperitoneal challenge with EEEV strain FL93-939. (a) Body temperature (b) Body weight. Error bars indicate the standard deviations for triplicate experiments.

Finally, challenge virus loads in brain samples collected from EEEV/IRES-vaccinated mice on days 5-7 were below the detection limit (2 log10 PFU/g by plaque assay) as compared to ~ 106 PFU/ml in the brain of sham-vaccinated mice with PBS.

3.4 Viral Replication in mosquitoes

To assess the replication competence of EEEV/IRES in mosquitoes, we inoculated intrathoracically adult female Ae. albopictus with undiluted virus stock of either EEEV/IRES, wt FL93-939 strain or PBS. Intrathoracic inoculation was used rather than oral exposure because this is the most permissive route of mosquito infection by arboviruses. Homogenate extracts of mosquitoes inoculated with EEEV/IRES (N=15) or PBS (N=10) produced no detectable CPE up to 5 days PI. In contrast, homogenate extracts of all mosquitoes receiving FL-93-939 (N=15) produced extensive CPE on Vero cells by 2 days PI. Mosquito homogenates were also assayed by RT-PCR to detect viral RNA. No amplicons were detected from the homogenate extracts of mosquitoes inoculated with EEEV/IRES or PBS by gel electrophoresis, whereas all mosquito extracts injected with FL93-939 produced strong bands of the expected size (~ 700 bps) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Reverse transcription polymerase detection of viral replication in representative mosquitoes inoculated intrathoracically with EEEV/IRES, FL93-939 and PBS. Lanes 1-10: IRES/EEEV; Lanes 11-15: wt EEEV strain FL93-939; lane 16: PBS and Lanes 17-18: molecular weight markers.

4. Discussion

Traditionally, live-attenuated RNA virus vaccines have been generated by serial passage through cell cultures, which results in attenuation that is dependent on a small numbers of point mutations [43, 44, 45, 46]. Because of the instability of the genome during RNA virus replication, these point mutations are likely to revert in vivo, or the virus may acquire a compensatory mutation(s) that can restore virulence. The live-attenuated VEE vaccine, TC-83 is a good example. This vaccine, developed in 1961 by serial tissue culture passage of the virulent Trinidad donkey (TRD) strain, relies on only 2 mutations in the TRD genome for attenuation: one at position 3 in the 5′ non coding region and a second that encodes a Thr-to-Arg substitution at position 120 in the E2 envelope glycoprotein (47, 48, 49, 50). Although, TC-83 is quite effective in equids, it has several disadvantages that prevent it from being licensed for human use. About 20% of the vaccinees develop illness after vaccination, including 5% who develop a relatively-severe fibrile desease that resembles naturally acquired VEE. In addition to its high reactogenicity rate, TC-83 also fails to induce any detectable immune response in ca. 20% of the vaccine recipients (51). A major concern with vaccines like TC-83 produced from wt alphaviruses, which rely on small number of point mutations, is that they may revert or evolve in unanticipated ways into a virulent strain.

To develop an effective, live-attenuated vaccine against EEE, a novel attenuation approach was tested with the TC-83 strain [37]. An EMCV IRES was used to drive translation of the structural protein genes from the genomic RNA after inactivation of the subgenomic promoter. Because the EMCV IRES is translated inefficiently in insect cells, this TC-83 variant was incapable of infecting mosquitoes, an important safety feature for live arboviral vaccines.

We used this approach to generate a vaccine against EEE. Our initial results indicate that the resultant EEEV/IRES is highly attenuated in 3-4-week-old mice and induces no detectable viremia or any signs of disease, febrile response, or growth delays. All mice developed antibodies that neutralized wt EEEV, and were protected against highly virulent EEEV strain FL93-939, with no clinical signs of disease. Also, no challenge EEEV was detected in the brains of vaccinated mice on days 5-7, whereas, high titers were present in the sham-vaccinated mice. In vitro and in vivo mosquito infection experiments reveal that the IRES based attenuation of FL93-939 makes the virus completely incapable of replication in Aedes albopictus. The consensus genome sequence of the candidate vaccine after 5 serial passages was unchanged. However, we identified 4 minority population mutations: 1 in the capsid and the remaining 3 in the E2 protein gene. The two mutations in the E2 glycoprotein (T72 → K and Q194 → R) could have an effect on glycosamimine-glycan binding as shown for positively charged E2 mutations in other alphaviruses [52, 53, 54].

Additional studies are needed to more fully assess the potential of our vaccine for human use. The stability of attenuation, and the potential for viremia in other mammalian or avain hosts also needs to be assessed. Laboratory infections and experimental studies in animals demonstrate that EEEV is infectious by the aerosol route, which could be exploited by a bioterrorist. Therefore, protection against EEEV aerosol challenge is also needed, ultimately in nonhuman primates.

In summary, we generated an attenuated strain of EEEV by inactivating the subgenomic promoter and driving translation of the structural protein genes using an EMCV IRES. Our EEEV vaccine candidate appears to be safe and efficacious in mice and is incapable of infecting mosquitoes. Further testing of this vaccine strain is needed to assess its suitability for human use. However, considering the promise of this attenuation approach in another alphavirus, chikungunya [38], the IRES-based design appears to be suitable for vaccine development for a wide range of alphaviral diseseas.

Highlights.

Design of a recombinant EEE virus (EEEV/IRES), as a candidate vaccine for EEEV

Design of a recombinant EEE virus (EEEV/IRES), as a candidate vaccine for EEEV

Subgenomic promoter of wild type EEEV inactivated by IRES-based attenuation approach

Subgenomic promoter of wild type EEEV inactivated by IRES-based attenuation approach

Virulence, viremia and efficacy of EEEV/IRES tested in murine model

Virulence, viremia and efficacy of EEEV/IRES tested in murine model

EEEV/IRES incapable of infecting mosquitoes

EEEV/IRES incapable of infecting mosquitoes

Acknowledgements

We thank Rui Mei Yun for excellent technical assistance and Jing Huang for rearing mosquitoes and assistance with mosquito work. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) through the Western Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant U54 AIO57156.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Calisher CH, Karabatsos N. Arbovirus subgroups: defination and geographical distribution. In: Monath TP, editor. The arboviruses:epidemiology and ecology. CRC press, Inc.; Boca Raton, Fl.: 1988. pp. 19–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porterfield JS. Antigenic characteristics and classification of togaviridae. In: Schlesinger RW, editor. The togaviruses: biology, structure, replication. Academic Press Inc.; New York: 1980. pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feemster RF, Haymaker W. Eastern equine encephalitis. Neurology. 1958 Nov;8(11):882–883. doi: 10.1212/wnl.8.11.882-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson RE, Peters CJ. In: Fields Virology. Fields DMKBN, Howley PM, editors. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia: 1996. rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casals J. Antigenic variants of Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus. J. Exp. Med. 1964 Apr 1;119:547–565. doi: 10.1084/jem.119.4.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brault AC, Powers AM, Chavez CL, Lopez RN, Cachón MF, Gutierrez LF, Kang W, Tesh RB, Shope RE, Weaver SC. Genetic and antigenic diversity among eastern equine encephalitis viruses from North, Central, and South America. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999 Oct;61(4):579–586. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver SC, Hagenbaugh A, Bellew LA, Gousset L, Mallampalli V, Holland JJ, Scott TW. Evolution of alphaviruses in the eastern equine encephalomyelitis complex. J Virol. 1994 Jan;68(1):158–169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.158-169.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver SC. Eastern equine encephalitis. In: Service MW, editor. The encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted infections. CAB International; Wallingord, UK: 2001. pp. 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver SC, Tesh RB, Shoppe RE. Alphavirus infections. In: Guerrant RI, Walker DH, Weller PF, editors. Tropical Infectious diseases principles, pathogens and practice. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 1281–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai TF, Weaver SC, Monath TP. Alphaviruses. In: Richmann DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, editors. Clinical Virology. ASM Press; Washington DC: 2002. pp. 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel P, Kell WM, Fritz DL, Parker MD, Schoepp RJ. Early events in the pathogenesis of eastern equine encephalitis virus in mice. Am J Pathol. 2005 Jan;166(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62241-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilar PV, Paessler S, Carrara AS, Baron S, Poast J, Wang E, Moncayo AC, Anishchenko M, Watts D, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Variation in interferon sensitivity and induction among strains of eastern equine encephalitis virus. J Virol. 2005 Sep;79(17):11300–11310. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11300-11310.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pratt WD, Gibbs P, Pitt ML, Schmaljohn AL. Use of telemetry to assess vaccine-induced protection against parenteral and aerosol infections of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in non-human primates. Vaccine. 1998 May-Jun;16(9-10):1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt WD, Davis NL, Johnston RE, Smith JF. Genetically engineered, live attenuated vaccines for Venezuelan equine encephalitis: testing in animal models. Vaccine. 2003 Sep 8;21(25-26):3854–3862. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed DS, Lind CM, Lackemeyer MG, Sullivan LJ, Pratt WD, Parker MD. Genetically engineered, live, attenuated vaccines protect nonhuman primates against aerosol challenge with virulent IE strain of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Vaccine. 2005 May 2;23(24):3139–3147. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilcek J. Production of interferon by newborn and adult mice infected with sindbis virus. Virology. 1964 Apr;22:651–652. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(64)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown A, Vosdingh R, Zebovitz E. Attenuation and immunogenicity of ts mutants of Eastern encephalitis virus for mice. J. Gen. Virol. 1975;27(1):111–116. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-27-1-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown A, Officer JE. An attenuated variant of Eastern encephalitis virus: biological properties and protection induced in mice. Arch Virol. 1975;47(2):123–138. doi: 10.1007/BF01320552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MaireIII LF, McKinney RW. An inactivated eastern EEV vaccine propagated in chick-embryo cell culture. American J of Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19(1):119–122. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartelloni PJ, McKinney RW, Duffy TP, Cole FE., Jr An inactivated eastern equine encephalomyelitis vaccine propagated in chick-embryo cell culture. II. Clinical and serologic responses in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970 Jan;19(1):123–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tengelsen LA, Bowen RA, Royals MA, Campbell GL, Komar N, Craven RB. Response to and efficacy of vaccination against eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus in emus. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001 May 1;218(9):1469–1473. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jochim MM, Barber TL. Immune response of horses after simultaneous or sequential vaccination against eastern, western, and Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974 Oct 1;165(7):621–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snoeyenbos GH, Weinack OM, Rosenau BJ. Immunization of pheasants for Eastern encephalitis. Avian Dis. 1978 Jul-Sep;22(3):386–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark GG, Dein FJ, Crabbs CL, Carpenter JW, Watts DM. Antibody response of sandhill and whooping cranes to an eastern equine encephalitis virus vaccine. J Wildl Dis. 1987 Oct;23(4):539–544. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-23.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elvinger F, Baldwin CA, Liggett AD, Tang KN, Dove CR. Protection of pigs by vaccination of pregnant sows against eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus. Vet Microbiol. 1996 Aug;51(3-4):229–239. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsen GH, Turell MJ, Pagac BB. Efficacy of eastern equine encephalitis immunization in whooping cranes. J Wildl Dis. 1997 Apr;33(2):312–315. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-33.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber TL, Walton TE, Lewis KJ. Efficacy of trivalent inactivated encephalomyelitis virus vaccine in horses. Am J Vet Res. 1978 Apr;39(4):621–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurer FD, Kuttler KL, Yager RH, Warner A. Immunization of laboratory workers with purified trivalent equine encephalomyelitis vaccine. J Immunol. 1952 Jan;68(1):109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franklin RP, Kinde H. EEEV infection in horse from CA. Emerging Infect diseases. 2002;8(3):283–288. doi: 10.3201/eid0803.010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawley RJ, Eitzen EM., Jr Biological weapons- a primer for microbiologists. Annual Review Microbiology. 2001;55:235–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang E, Poetrakova A, Adams PA, Aguilar PV, Kang W, Paessler S, Volk SM, Frolov I, Weaver SC. Chimeric sindbis/eastern equine encephalitis vaccine candidates are highly attenuated and immunogenic in mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:7573–7581. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoepp RJ, Smith JF, Parker MD. Recombinant chimeric western and eastern equine encephalitis viruses as potential vaccine candidates. Virology. 2002 Oct 25;302(2):299–309. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenney JL, Volk SM, Pandya J, Wang E, Liang X, Weaver SC. Stability of RNA virus attenuation approaches. Vaccine. 2011 Mar 9;29(12):2230–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen CE, Jr, Robinson DM, Cole FE., Jr Isolation of the vaccine strain of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus from mosquitoes in Louisiana. Am J Epidemiol. 1972 May;95(5):490–496. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arrigo NC, Watts DM, Frolov I, Weaver SC. Experimental Infection of Aedes sollicitans and Aedes taeniorhynchus with Two Chimeric Sindbis/Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus Vaccine Candidates. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2008 Jan;78(1):93–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein Y, Faktor O, Elroy-Stein O, Levi BZ. The use of bi-cistronic transfer vectors for the baculovirus expression system. J Biotechnol. 1999 Sep 24;75(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volkova E, Frolova E, Darwin JR, Forrester NL, Weaver SC, Frolov I. IRES-dependent replication of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus makes it highly attenuated and incapable of replicating in mosquito cells. Virology. 2008 Jul 20;377(1):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plante KS, Wang E, Partidos CD, Weger J, Gorchakov R, Tsetsarkin KA, et al. Novel chikungunya vaccine candidate with an IRES-based attenuation and host range alteration mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002142. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguilar PV, Adams AP, Wang E, Kang W, Carrara AS, Anishchenko M, et al. Structural and nonstructural protein genome regions of eastern equine encephalitis virus are determinants of interferon sensitivity and murine virulence. J Virol. 2008;82(10):4920–4930. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02514-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaty BJ, Calisher CH, Shope RE. Arboviruses. In: Lennete ET, Lnnete DA, editors. Diagnostic procedures for viral, rickettsial and chlamydial infections. 7th edition American Public Health Association; Washington DC: pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsetsarkin KA, Chen R, Leal G, Forrester N, Higgs S, Huang J, Weaver SC. Chikungunya virus emergence is constrained in Asia by lineage-specific adaptive landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 May 10;108(19):7872–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018344108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrett PN, Mundit W, Kistner O, Howard MK. Vero cell platform in vaccine production: moving towards cell culture-based viral vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2009;8(5):607–618. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minor P. Vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV): impact on poliomyelitis eradication. Vaccine. 2009 May 20;27:2649–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kew OM, Sutter RW, deGourville EM, Dowdle WR, Pallansch MA. Vaccine-derived polioviruses and the endgame strategy for global polio eradication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:587–635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs BL, Langland JO, Kibler KV, Denzler KL, White SD, Holechek SA, et al. Vaccinia virus vaccines: past, present and future. Antiviral Res. 2009 Oct;84(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrett AD, Teuwen DE. Yellow fever vaccine: how does it work and why do rare cases of serious adverse events take place. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009 June 3;21:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis NL, Powell N, Greenwald GF, Willis LV, Johnson BJB, Smith JF, Johnston RE. Attenuating mutations in the E2 glycoprotein gene of Venezuelan equine encephalitis: Construction of single and multiple mutants in a full-length clone. Virology. 1991;183:20–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90114-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinney RM, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Sneider JM, Roehrig JT, Woodward TM, Trent DW. Attenuation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus strain TC-83 is encoded by the 5′ -non coding region and the E2 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1993;67:1269–1277. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1269-1277.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinney RM, Johnson BJB, Welch JB, Tsuchiya KR, Trent DW. The full-length nucleotide sequences of the virulent Trinidad donkey strain of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and its attenuated vaccine derivative, strain TC-83. Virology. 1989;170:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White LJ, Wang JG, Davis NL, Johnston RE. Role of Alpha/Beta Interferon in Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus Pathogenesis: Effect of an Attenuating Mutation in the 5′ Untranslated Region. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3706–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3706-3718.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pittman PR, Makuch RS, Mangiafico JA, Cannon TL, Gibbs PH, Peters CJ. Long-term duration of detectable neutralizing antibodies after administration of live-attenuated VEE vaccine and following booster vaccination with inactivated VEE vaccine. Vaccine. 1996 Mar;14(4):337–43. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00168-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernard KA, Klimstra WB, Johnston RE. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus confer heparan sulfate interaction, low morbidity and rapid clearance from blood of mice. Virology. 2000 Oct 10;276(1):93–103. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee P, Knight R, Smit JM, Wilschut J, Griffin DE. A single mutation in the E2 glycoprotein important for neurovirulence influences binding of sindbis virus to neuroblastoma cells. J. Virol. 2002 June;76(12):6302–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6302-6310.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang E, Brault AC, Powers AM, Kang W, Weaver SC. Glycosaminoglycan binding properties of natural Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus isolates. J. Virol. 2003 Jan;77(2):1204–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1204-1210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]