Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate whether anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels could be predict ovarian poor/hyper response and IVF cycle outcome.

Methods

Between May 2010 and January 2011, serum AMH levels were evaluated with retrospective analysis. Three hundred seventy infertile women undergoing 461 IVF cycles between the ages of 20 and 42 were studied. We defined the poor response as the number of oocytes retrieved was equal or less than 3, and the hyper response as more than 25 oocytes retrieved. Serum AMH was measured by commercial enzyme-linked immunoassay.

Results

The number of oocytes retrieved was more correlated with the serum AMH level (r=0.781, p<0.01) than serum FSH (r=-0.412, p<0.01). The cut-off value of serum AMH levels for poor response was 1.05 ng/mL (receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curves/area under the curve [AUC], ROCAUC=0.85, sensitivity 74%, specificity 87%). Hyper response cut-off value was 3.55 ng/mL (ROCAUC=0.91, sensitivity 94%, specificity 81%). When the study group was divided according to the serum AMH levels (low: <1.05 ng/mL, middle: 1.05 ng/mL - 3.55 ng/mL, high: >3.55 ng/mL), the groups showed no statistical differences in mature oocyte rates (71.6% vs. 76.5% vs. 74.8%) or fertilization rates (76.9% vs. 76.6% vs. 73.8%), but showed significant differences in clinical pregnancy rates (21.7% vs. 24.1% vs. 40.8%, p=0.017).

Conclusion

The serum AMH level can be used to predict the number of oocytes retrieved in patients, distinguishing poor and high responders.

Keywords: Anti-Müllerian Hormone, Ovarian Response, Poor Response, Hyper Reponse, In Vitro Fertilization, Human

Introduction

In order to do appropriate controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) during IVF, the evaluation of the ovarian reserve is necessary [1,2]. Assessment of the ovarian reserve via age plays an important role in evaluation, but age by itself does not accurately predict the ovarian reserve. Traditionally, there are several ovarian reserve tests, including those that test for biochemical and ultrasonographic markers. Basal FSH, E2 and inhibin B levels are used as biochemical markers. But, their values are influenced by the menstrual cycle and have limited use for predicting poor and high responders. Ultrasonographic markers, such as antral follicle count (AFC) and ovarian volumes have been shown to be affected by interobserver variation [2-5].

Recently, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) has been evaluated as a potential novel clinical marker of ovarian reserve [6-10]. AMH is a dimeric glycoprotein belonging to the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family. AMH is secreted by sertoli cells in males and inhibits the development of the Müllerian ducts in the male fetus [11,12]. In females, it is secreted by the granulosa cells in the postpubertal age and controls the development of primary follicles by inhibiting further recruitment of other follicles during folliculogenesis [13]. Serum AMH level is closely related to the AFC, inhibin B, and basal E2. The AMH level shows low variability even during changes over the course of the menstrual cycle [14,15]. Recent studies have shown that AMH could be a predictor of ovarian reserve and the success rates of IVF [16-18]. However, some studies could not find to predict power of pregnancy outcomes [19,20].

The aim of this study was therefore to investigate whether AMH levels are associated with ovarian response and IVF cycle outcomes.

Methods

1. Study population

Between May 2010 and January 2011, serum AMH levels were evaluated with retrospective analysis. The study population included a total of 370 infertile women aged between 20 and 42 years who had undergone 461 IVF cycles. Exclusion criteria consisted of the following factors: 1) Polycystic ovary syndrome, 2) previous history of ovarian surgery (including oophorectomy and enucleation of an ovarian cyst), 3) body mass index≥30 kg/m2, 4) other endocrinological disease (thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, Cushing's syndrome). The study group was divided into three groups according to the number of oocytes retrieved. Patients with an oocyte count of three or less were considered poor responders, and patients with more than four, and less than twenty-four as normal responders, and patients with more than twenty-five as high responders. We analyzed ovarian response and IVF outcomes according to serum AMH levels.

2. Blood sampling and hormones assays

On day 2-3 of a menstrual cycle, blood sample assays of AMH, FSH, E2, and LH were obtained by venipuncture. Serum AMH levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay using an AMH/MIS EIA kit, which was a two-immunological-step sandwich-type assay (Immunotech version; Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France). First, the hormone was captured by a monoclonal antibody bound to the microtiter plate. Then, another monoclonal antibody with streptavidin-peroxidase bound to the solid phase antibody-antigen complex. After incubation, the antibody-antigen complex was detected by the addition of a chromogenic substrate. The serum AMH concentration was represented by the intensity of the coloration in the blood samples and then converted to ng/mL (conversion factor to pmol/L=ng/mL×7.14). The measurement range of the assay was from 0.14 ng/mL to 21 ng/mL. Serum AMH values below the reported clinical level of measurement (0.14 ng/mL) were treated as a zero value for analysis. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 12.3% and 14.2%, respectively.

Serum levels of FSH, LH, and E2 were determined using a Modular E170. More blood samples of E2 and LH were collected on the day of administration of hCG and measured in the same way.

3. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

On day 2-3 of the menstrual cycle, pelvic cavity abnormalities including ovarian tumors were checked for through a pelvic ultrasound. The patients underwent IVF treatment using a long down-regulation or short flare-up protocol with GnRH agonist or a GnRH antagonist protocol. In the GnRH agonist protocol, pituitary suppression was initiated with buserelin acetate (Superfact®, Sanofi-Aventis, Frankfrut, Germany) 0.5 mg or leuprolide acetate (Lucrin®, Abbot Lab, Chicago, IL, USA) 0.1 mg, subcutaneous injection, from day 3 of the cycle to the day of hCG administration. GnRH antagonist, a daily 0.25 mg subcutaneous injection of (Cetrorelix acetate, Cetrotide®, Serono, Darmstadt, Switzerland or ganirelix acetate (Orgalutran®, Schering-plough, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) was administered when the follicles were more than 12 mm in diameter or serum E2 concentrations were greater than 200 pg/mL. The dosage of gonadotrophin was determined by the age of the patient and the ovarian response of the previous cycle. The stimulation was monitored through follicle size and serum E2 levels. When a dominant follicle ≥ 18 mm in diameter was detected by ultrasonography, 250 µg choriogonadotropin-alfa (Ovidrel®, Serono, Roma, Italy) was administered. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval was performed 36 hours after choriogonadotropin-alfa injection. We performed IVF or ICSI with either ejaculated sperm or surgically retrieved sperm. The embryos were transferred into the uterine cavity on day 3-5 after oocyte retrieval. Pregnancy was determined by a serial serum β-hCG level of >5 mIL/mL at 12 days after the oocyte retrieval. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of a intrauterine gestational sac by ultrasonography at approximately 5 weeks of pregnancy.

4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis were used for statistical analysis. Each variable is presented as mean±SD. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

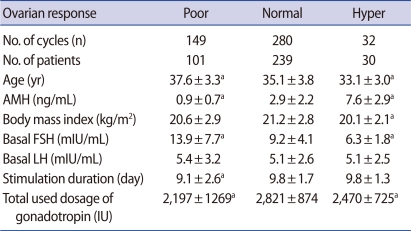

When groups were divided according to the number of oocytes retrieved, the age of poor, normal and high responders showed decreasing pattern in each group (37.6±3.3, 35.1±3.8, 33.1±3.0; p<0.05). The AMH level showed increasing pattern in each group (0.9±0.7, 2.9±2.2, 7.6±2.9; p<0.001). The basal FSH level among the three groups shows significant differences (13.9±7.7, 9.2±4.1, 6.3±1.8; p<0.01) (Table 1). The number of oocytes retrieved was more correlated with the serum AMH level (r=0.781, p<0.01) than serum FSH (r=-0.412, p<0.01) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Basal characteristics of the study population according to ovarian response

Values are presented as mean±SD.

AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone.

ap<0.05: compared to normal responder.

Figure 1.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), FSH and number of oocytes retrieved (A). AMH is strongly correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved (r=0.781) (p<0.01). (B) FSH is correlated negatively with the number of oocytes retrieved (r=-0.412) (p<0.01).

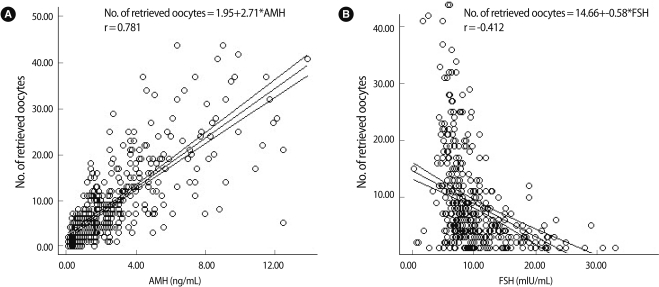

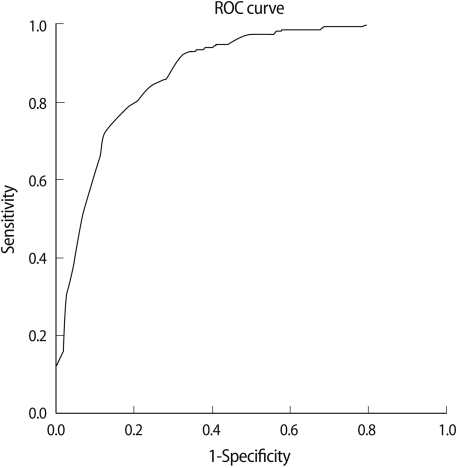

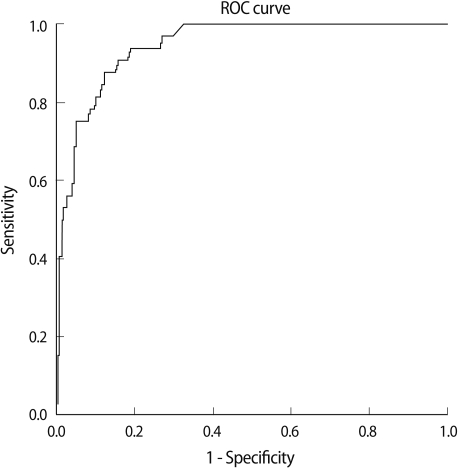

We analyzed the cut-off value of AMH by using the ROC curve to predict poor response and hyper response by the number of oocytes retrieved. The cut-off value of serum AMH levels for poor response was 1.05 ng/mL (ROC curves/area under the curve [AUC], ROCAUC=0.85; sensitivity 74%, specificity 87%) (Figure 2). The cut-off value of serum AMH levels for hyper response was 3.55 ng/mL (ROCAUC=0.91, sensitivity 94%, specificity 81%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cut-off value of serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) for poor responders. Cut-off AMH value=1.05 ng/mL (receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curves/area under the curve [AUC], ROCAUC=0.85, sensitivity 74%, specificity 87%).

Figure 3.

Cut-off value of serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) for high responders. Cut-off AMH value=3.55 ng/mL (receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curves/area under the curve [AUC], ROCAUC=0.91, sensitivity 94%, specificity 81%).

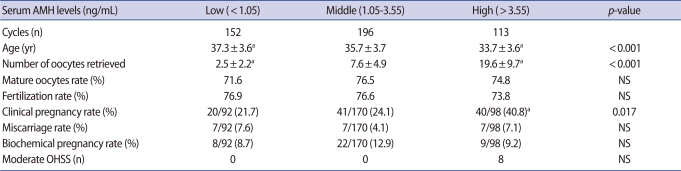

When the study group was divided according to serum AMH levels (low: AMH<1.05 ng/mL, middle: 1.05 ng/mL≤AMH≤3.55 ng/mL, high: AMH>3.55 ng/mL), they showed no statistical difference in mature oocyte rates (71.6% vs. 76.5% vs. 74.8%) or fertilization rates (76.9% vs. 76.6% vs. 73.8%) (Table 2). Statistical differences were found in the number of oocytes retrieved (2.5±2.2 vs. 7.6±4.9 vs. 19.6±9.7; p<0.001) and age (37.3±3.6 vs. 35.7±3.7 vs. 33.7±3.6; p<0.001) and clinical pregnancy rates (21.7% vs. 24.1% vs. 40.8%; p=0.017) (Table 2).

Table 2.

IVF outcome according to the serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) level

Values are presented as mean±SD.

NS, not significant; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

ap-value: compared to middle AMH group.

Discussion

Decreased ovarian reserve in advanced-aged women reduces the possibility of pregnancy. AMH has recently received attention as an indicator of women's fertility. This hormone appears in the 36th week of gestation, decreases continuously through puberty, and becomes undetectable when menopause occurs [21,22].

In IVF treatment, age, basal FSH, AFC, and inhibin B are useful as indicators in assessing basal ovarian reserve, but these indicators have several limitations.

FSH level predicts poor responders [23]. However, in a meta-analysis, it has been concluded that basal FSH is not a useful predictor of IVF outcome [24], possibly because of intercycle variability [25]. AMH has little intercycle variability in comparison FSH, and AMH has been known to correlate with the AFC, the number of oocytes retrieved that reflect ovarian reserve.

In this study, AMH level has closely correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved.

A prospective study comparing serum AMH with AFC in 130 COH cycles showed that the two markers performed similarly in the prediction of the number of oocytes retrieved [26]. Bancsi et al. [27] demonstrated that the AFC provides better prognostic information on the occurrence of poor response during hormone stimulation for IVF than does the patient's chronological age and the currently used endocrine markers. However, conducting an antral follicle count has limited intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility. Considering these points, AMH appears to be the best predictor of ovarian reserve.

La Marca et al. [28] defined the cut-off value of serum AMH level as 0.5 ng/mL for the prediction of poor response (sensitivity 85.0%, specificity 82.3%). Seifer et al. [29] defined the mean serum AMH level as 1.0±0.4 ng/mL for the prediction of the group with ≤6 oocytes retrieved.

In addition, Eldar-Geva et al. [30] considered AMH level not only as a quantitative indicator of the number of oocytes retrieved but also as a qualitative indicator of oocyte quality, fertilization rate, and clinical pregnancy rate. Though this relationship between AMH level and oocyte quality, fertilization rate, and clinical pregnancy rate has been studied, no distinct correlation among them has been revealed.

Buyuk et al. [31] found that the clinical pregnancy rate was higher among women with a random serum AMH>0.6 ng/mL (28% vs. 14%); however, the difference was not statistically significant. Silberstein et al. [32] reported good embryo quality when AMH level >2.7 ng/mL on the day of hCG administration. Ebner et al. [33] reported that on day 3 of the menstrual cycle, the AMH level was associated with the quality of oocytes. Wang et al. [34] found that AMH has limited predictive value for IVF outcomes in the two extremes of female reproduction. Women between 34 and 41 years old with higher serum AMH concentrations are associated with significantly greater chances of pregnancy (p<0.01). However, Smeenk et al. [19] found that the AMH level on day 3 of the menstrual cycle was not related to the quality of oocytes and pregnancy rate.

In this study, the mature oocyte rate and the fertilization rate did not show any significant differences according to the AMH level. Qualitative criteria such as the morphology of the retrieved oocytes and embryo should therefore be considered in an expanded study.

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective design and the absence of antral follicle counts.

In conclusion, serum AMH level is more useful than the basal FSH level that is currently being used. This study we are able to inform cut-off values to predict poor response and hyper response during IVF treatment through the serum AMH level. This cut-off value may be supported by further study.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kwee J, Elting MW, Schats R, Bezemer PD, Lambalk CB, Schoemaker J. Comparison of endocrine tests with respect to their predictive value on the outcome of ovarian hyperstimulation in IVF treatment: results of a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1422–1427. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Defining ovarian reserve to better understand ovarian aging. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukulmez O, Arici A. Assessment of ovarian reserve. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:231–237. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200406000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sills ES, Alper MM, Walsh AP. Ovarian reserve screening in infertility: practical applications and theoretical directions for research. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Azemi M, Killick SR, Duffy S, Pye C, Refaat B, Hill N, et al. Multi-marker assessment of ovarian reserve predicts oocyte yield after ovulation induction. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:414–422. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART) Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:113–130. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almog B, Shehata F, Suissa S, Holzer H, Shalom-Paz E, La Marca A, et al. Age-related normograms of serum antimullerian hormone levels in a population of infertile women: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2359–2363.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barad DH, Weghofer A, Gleicher N. Utility of age-specific serum anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Giulini S, Traglia M, Argento C, Sala C, et al. Normal serum concentrations of anti-Mullerian hormone in women with regular menstrual cycles. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seifer DB, Baker VL, Leader B, et al. Age-specific serum anti-Mullerian hormone values for 17,120 women presenting to fertility centers within the United States. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:747–750. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behringer RR, Finegold MJ, Cate RL. Mullerian-inhibiting substance function during mammalian sexual development. Cell. 1994;79:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigier B, Picard JY, Tran D, Legeai L, Josso N. Production of anti-Mullerian hormone: another homology between Sertoli and granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1315–1320. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-4-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visser JA, de Jong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti-Mullerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction. 2006;131:1–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruijters MJ, Visser JA, Durlinger AL, Themmen AP. Anti-Mullerian hormone and its role in ovarian function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;211:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Guibourdenche J, Frydman R, Taieb J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone is more strongly related to ovarian follicular status than serum inhibin B, estradiol, FSH and LH on day 3. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:323–327. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lekamge DN, Barry M, Kolo M, Lane M, Gilchrist RB, Tremellen KP. Anti-Mullerian hormone as a predictor of IVF outcome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:602–610. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wunder DM, Guibourdenche J, Birkhauser MH, Bersinger NA. Anti-Mullerian hormone and inhibin B as predictors of pregnancy after treatment by in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2203–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barad DH, Weghofer A, Gleicher N. Comparing anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) as predictors of ovarian function. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1553–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smeenk JM, Sweep FC, Zielhuis GA, Kremer JA, Thomas CM, Braat DD. Antimullerian hormone predicts ovarian responsiveness, but not embryo quality or pregnancy, after in vitro fertilization or intracyoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TH, Liu CH, Huang CC, Wu YL, Shih YT, Ho HN, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone and estradiol levels as predictors of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in assisted reproduction technology cycles. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:160–167. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Vet A, Laven JS, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Fauser BC. Antimullerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MM, Donahoe PK, Hasegawa T, Silverman B, Crist GB, Best S, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance in humans: normal levels from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:571–576. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurema MW, Bracero NJ, Garcia JE. Fine tuning cycle day 3 hormonal assessment of ovarian reserve improves in vitro fertilization outcome in gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist cycles. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1156–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)02159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Mol BW, Habbema JD, te Velde ER. Performance of basal follicle-stimulating hormone in the prediction of poor ovarian response and failure to become pregnant after in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Habbema JD, te Velde ER. Predicting poor ovarian response in IVF: use of repeat basal FSH measurement. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:187–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, te Velde ER, Fauser BC, Bancsi LF, de Jong FH, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3065–3071. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Eijkemans MJ, de Jong FH, Habbema JD, te Velde ER. Predictors of poor ovarian response in in vitro fertilization: a prospective study comparing basal markers of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:328–336. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Marca A, Giulini S, Tirelli A, Bertucci E, Marsella T, Xella S, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:766–771. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seifer DB, MacLaughlin DT, Christian BP, Feng B, Shelden RM. Early follicular serum mullerian-inhibiting substance levels are associated with ovarian response during assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:468–471. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eldar-Geva T, Ben-Chetrit A, Spitz IM, Rabinowitz R, Markowitz E, Mimoni T, et al. Dynamic assays of inhibin B, anti-Mullerian hormone and estradiol following FSH stimulation and ovarian ultrasonography as predictors of IVF outcome. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3178–3183. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buyuk E, Seifer DB, Younger J, Grazi RV, Lieman H. Random anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) is a predictor of ovarian response in women with elevated baseline early follicular follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2369–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silberstein T, MacLaughlin DT, Shai I, Trimarchi JR, Lambert-Messerlian G, Seifer DB, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:159–163. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebner T, Sommergruber M, Moser M, Shebl O, Schreier-Lechner E, Tews G. Basal level of anti-Mullerian hormone is associated with oocyte quality in stimulated cycles. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2022–2026. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JG, Douglas NC, Nakhuda GS, Choi JM, Park SJ, Thornton MH, et al. The association between anti-Mullerian hormone and IVF pregnancy outcomes is influenced by age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]