Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the ability of serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), FSH, and age to clinically predict ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) in IVF patients with endometriosis.

Methods

We evaluated 91 COH cycles, including 43 cycles with endometriosis (group I) and 48 cycles with male factor infertility (group II) from January to December, 2010. Patients were classified into study groups based on their surgical history of endometriosis-group Ia (without surgical history, n=16), group Ib (with a surgical history, n=27).

Results

The mean age was not significantly different between group I and group II. However, AMH and FSH were significantly different between group I and group II (1.9±1.9 ng/mL vs. 4.1±2.9 ng/mL, p<0.01; 13.1±7.2 mIU/mL vs. 8.6±3.3 mIU/mL, p<0.01). Furthermore, the number of retrieved oocytes and the number of matured oocytes were significantly lower in group I than in group II. In group II, AMH and FSH as well as age were significant predictors of retrieved oocytes on univariate analysis. Only the serum AMH level was a significant predictor of poor ovarian response in women with endometriosis.

Conclusion

Serum AMH may be a better predictor of the ovarian response of COH in patients with endometriosis than basal FSH or age. AMH level can be considered a useful clinical predictor of poor ovarian response in endometriosis patients.

Keywords: Anti-Müllerian hormone (Müllerian inhibiting substance), Ovarian stimulation, Endometriosis, In vitro fertilization, Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, Human

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue(glands and stroma) outside the uterus, which induces a chronic inflammatory reaction, scar tissue, and adhesions [1]. It is a frequent gynecological disorder that occurs in 6-10% of the female population and is more frequent in infertile women, where it occurs in 25-40% [2,3].

Women with endometriosis have a lower ovarian reserve and high basal FSH level than women of the same age who do not have endometriosis [4,5]. However, unlike women with a diminished ovarian reserve due to advanced reproductive age or incipient premature ovarian failure, women with endometriosis do not exhibit poor embryo quality or a reduced implantation rate [6]. Thus, assessment of ovarian reserve in women with endometriosis undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) has been an important problem. Many studies suggest that markers for ovarian reserve may behave differently in women with and without endometriosis [7,8]. However, there are few studies to identify markers of ovarian reserve and predict the response to COH in women with endometriosis.

Recently, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) has emerged as a novel marker for ovarian reserve [9-11]. AMH is expressed in the growing preantral or small antral follicles in the ovary [12] and reflects the recruited ovarian follicular pool [10]. Serum AMH levels decrease steadily with increasing age and are undetectable after menopause [13,14]. In assisted reproductive technology, serum AMH levels accurately reflect the total developing follicular cohort and predict the ovarian response to COH [15-17].

Several investigators demonstrated lower basal AMH levels among women with endometriosis [18]. However, there are few studies for correlation between serum AMH and ovarian response to COH in women with endometriosis. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical predictability of serum AMH, FSH, and age as predictors of ovarian response to COH in patients with endometriosis.

Methods

1. Study population

From January 1st, 2010 to December 31st, 2010, 2,163 non-donor, fresh IVF cycles performed in Cheil General Hospital and Women's Health Care Center with recorded AMH concentrations were retrospectively identified. The inclusion criteria of this study include the following factors: 1) infertility associated with endometriosis or male factor infertility, 2) age ≤43 years old, 3) body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2, 4) absence of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), 5) absence of other endocrine disease (thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, Cushing's syndrome). Following these criteria, the final study population consisted of 43 cycles with endometriosis as the study group (group I) and 48 cycles with exclusive male factor infertility as the control group (group II). In order to determine any differences according to surgery of endometriosis, the study groups were classified according to their surgical history-group Ia (without surgical history, n=16), group Ib (with surgical history, n=27). Poor ovarian response to COH was defined as a number of retrieved oocytes not exceeding three. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cheil General Hospital and Women's Healthcare Center, Kwandong University College of Medicine.

Serum AMH was drawn within 3 months prior to ovarian stimulation, independent of menstrual cycle day. Assays were performed by enzyme immunoassay using an AMH/MIS EIA kit (Immunotech version; Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France). On day 2-3 of the spontaneous menstrual cycle, the blood samples for the assay of FSH and E2 were obtained by venipuncture.

2. Ovarian stimulation protocol

An ovarian hyperstimulation protocol was initiated after confirming the lack of any growing follicle greater than 10 mm in diameter by ultrasound, and basal serum E2 not exceeding 50 pg/mL on day 2 or 3 of the menstrual cycle. Ovarian hyperstimulation was achieved either by short or long protocols using GnRH agonist leuprolide (Lucrin, Abott Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea) or short protocols using 0.25 mg GnRH antagonists (Cetrotide; Merck Serno, Geneva, Switzerland or Orgalutran; Schering-Plough Organon, Oss, the Netherlands). Recombinant hCG (Ovidrel, Merck Serno) was administered subcutaneously in a single 250 µg dose when a dominant follicle had reached a maximum diameter of 18 mm or greater. Follicle aspiration was performed approximately 34-36 hours after hCG administration for oocyte retrieval.

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons of data between groups were performed with the Student's t-test. Each variable is presented as mean±SD. Pearson's correlation and Spearman's correlation were utilized to analyze the correlations between variables. Areas under receiver operating characteristic curves were utilized to predict poor ovarian response to COH. A p-value of below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

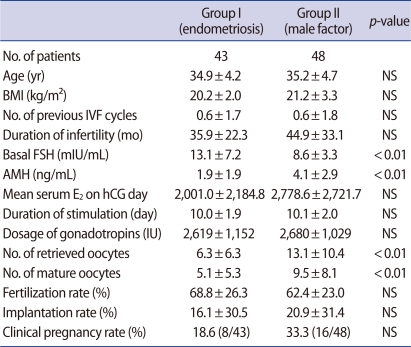

There was no significant difference in age, BMI, number of previous IVF cycles, or duration of infertility between the study group (group I) and the control group (group II) (Table 1). The serum AMH level was significantly lower in group I than group II (1.9±1.9 vs. 4.1±2.9), whereas the basal FSH level was significantly higher in group I than group II (13.1±7.2 vs. 8.6±3.3) (Figure 1). However, there was no significant difference in basal E2 levels. When we analyzed subgroups of the study group, there was no significant difference in age (35.7±3.2 vs. 34.4±4.6), AMH (1.6±1.1 vs. 2.1±2.2), FSH (10.9±4.4 vs. 14.3±8.2), the number of retrieved oocytes (5.8±5.3 vs. 6.5±6.9), or the number of matured oocytes (4.7±4.3 vs. 5.3±5.9) between group Ia and group Ib.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of IVF patients between women with endometriosis (group I) and women with male factor (group II)

The values are expressed as mean±SD.

BMI, body mass index; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; NS, not significant.

Figure 1.

Comparison of serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and serum FSH levels of women with endometriosis and women with male factor infertility (control).

There was no significant difference in the duration of stimulation or dosage of gonadotropins between group I and group II. However, the number of retrieved oocytes and number of mature oocytes were significantly fewer in group I than group II (Table 1).

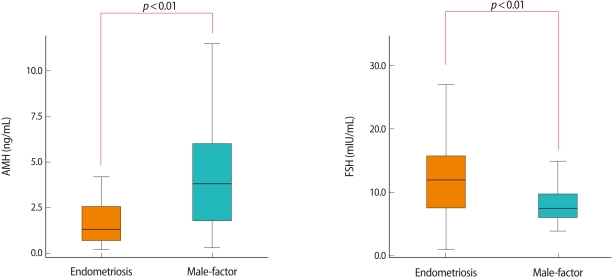

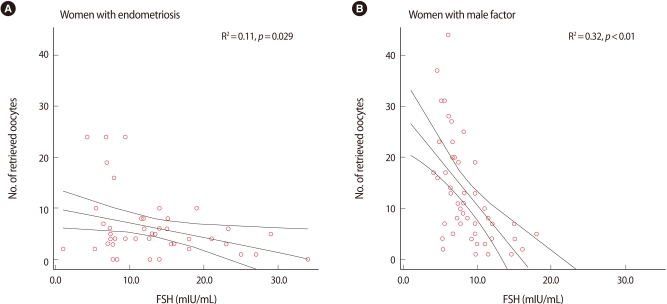

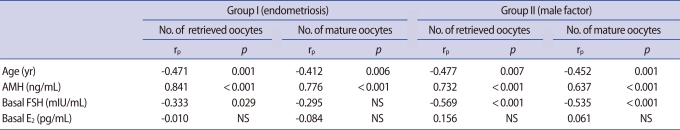

The number of retrieved oocytes was more correlated with the serum AMH level than with the serum FSH in both groups (Figures 2, 3). A significant negative correlation between age and variables of ovarian response was obtained for both groups. In addition, the serum AMH level was positively and significantly correlated with the number of retrieved oocytes and number of mature oocytes in both groups. However, the serum FSH was not correlated with the number of mature oocytes in group I (Table 2). In group Ia, only serum AMH was significantly correlated with the number of retrieved oocytes (rs=0.703, p<0.001), whereas in group Ib, AMH and age had a high correlation with the number of retrieved oocytes (rs=0.736, p<0.001, rs=0.640, p<0.001). However, in group Ia and group Ib, FSH did not present a correlation with the number of retrieved oocytes (rs=-0.209, not significant [NS], rs= -0.326, NS).

Figure 2.

Correlation between the number of retrieved oocytes and serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the number of retrieved oocytes and serum FSH level.

Table 2.

Correlation between the number of retrieved oocytes and serum AMH, FSH, and age in group I and II

AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; NS, not significant.

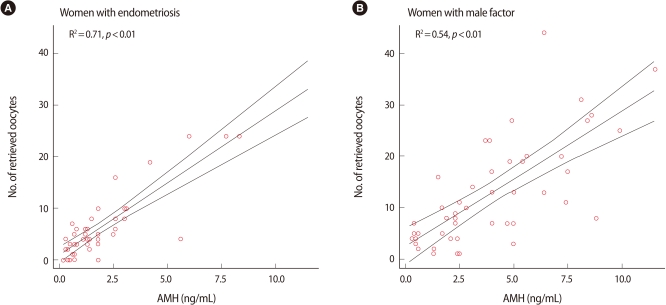

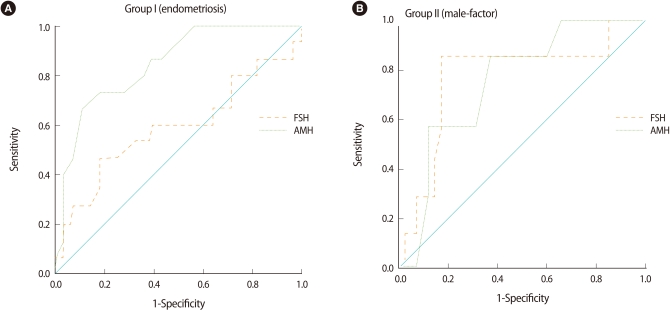

We also analyzed the cut-off value of AMH and FSH by using the receiver operating characteristic curve to predict poor ovarian response in both groups (Figure 4). We demonstrated that the serum AMH level was the most important marker, with a significant ability for determination of poor ovarian response in the study group (area under the curve [AUC]=0.845 [95% confidence interval, CI: 0.727-0.964]), with 73.3% sensitivity and 82.1% specificity, for AMH levels ≤0.95 ng/mL. However, basal FSH was not significant in group I (AUC=0.587 [95% CI: 0.391-0.782], NS) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for basal FSH and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), as predictors of a poor ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) in groups I and II.

Discussion

Although ART procedures have been successful in infertile women with endometriosis, poorer results are still expected for women with the disease [7]. Several studies have suggested that follicle and oocyte impairment eventually disrupts the reproductive function of women with endometriosis. Therefore, many investigators have attempted to identify markers of ovarian reserve also capable of predicting response to treatment in these women.

The current study showed that the serum AMH level showed a statistically significant positive correlation with the number of retrieved oocytes and the number of mature oocytes in both groups. However, there was no correlation between serum FSH and number of mature oocytes in women with endometriosis. These results indicate that in women with endometriosis, regardless of their surgical history, the serum AMH level might be a better marker for predicting the number of oocytes retrieved undergoing COH than serum FSH or age. Some studies have presented an association between serum AMH and ovarian function. Serum AMH decreases steadily with advancing age and declining ovarian function, whereas the other serum ovarian reserve tests such as FSH and inhibin B utilize cutoff values for normal ovarian function [11]. Therefore, serum AMH may be useful in women with endometriosis who present progressive loss of ovarian reserve with advancing disease. With similar results, Knauff et al. [19] reported that compared with inhibin B and antral follicle counts, AMH was more consistently correlated with the clinical degree of follicle pool depletion in young hypergonadotropic patients such as transient ovarian failure, incipient ovarian failure, and premature ovarian failure. That study suggested that AMH indicates a more accurate assessment of the follicle pool in young women presenting with elevated FSH levels.

In the current study, the serum AMH level was significantly lower in the study group when compared with that of the control group. Furthermore, the serum FSH level was significantly higher in the study group. Several studies have investigated ovarian reserve in endometriosis. Lemos et al. [18] demonstrated that infertile patients with minimal or mild endometriosis had decreased serum AMH compared to a control group. In that study, the two groups' serum FSH did not differ. However, Hock et al. [8] reported a significant increase in basal FSH levels in women with advanced endometriosis, supporting the idea of a progressive loss of ovarian function as the disease advances. Likewise, Falconer et al. [20] reported that women with endometriosis had significantly lower AMH in serum and follicular fluid, and higher concentrations of TNF, IL-15, and GM-CSF in the follicular fluid. They suggested that women with endometriosis have a reduced reproductive potential because of increased inflammatory activity. These results are similar to our findings. In the current study, the number of retrieved oocytes and the number of mature oocytes were significantly fewer in the study group than the control group. This suggests that endometriosis is associated with the reduction of ovarian reserve and poor ovarian response to COH.

Among the predictors of ovarian response, serum AMH compared to FSH had a several advantages such as low intercycle and intracycle variability, menstrual cycle-independent [21]. This study demonstrated that only the serum AMH level was significantly valuable in predicting a poor ovarian response for women with endometriosis. The cut-off value of serum AMH for poor response will be helpful determining treatment options for infertility in women with endometriosis. However, there are several limitations of this study such as retrospective design, small sample size. Therefore, large scale study should be performed to determine the consensual cut-off value in endometriosis.

In conclusion, compared with women who do not have endometriosis, the current study showed that the serum AMH level was significantly lower, and the serum FSH level was significantly higher in women with endometriosis. This study indicates that serum AMH represents a useful marker of ovarian response to COH in patients with endometriosis. In particular, it is useful for predicting the ovarian response to COH in women with a high serum FSH level.

Footnotes

*Poster presented at the 27th annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, Stockholm, Sweden, July 3-6, 2011.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D'Hooghe T, Dunselman G, Greb R, et al. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2698–2704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozkan S, Murk W, Arici A. Endometriosis and infertility: epidemiology and evidence-based treatments. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:92–100. doi: 10.1196/annals.1434.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahutte NG, Arici A. Endometriosis and assisted reproductive technologies: are outcomes affected? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:275–279. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HO, Park CW, Song IO, Koong MK. IVF/ICSI outcomes of women with minimal to mild endometriosis associated infertility and unexplained infertility. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:322–328. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Mahutte N, Fragouli Y, Arici A, Sakkas D. Women with advanced-stage endometriosis and previous surgery respond less well to gonadotropin stimulation, but have similar IVF implantation and delivery rates compared with women with tubal factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1568–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R, Coutifaris C. Effect of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1148–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hock DL, Sharafi K, Dagostino L, Kemmann E, Seifer DB. Contribution of diminished ovarian reserve to hypofertility associated with endometriosis. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almog B, Shehata F, Suissa S, Holzer H, Shalom-Paz E, La Marca A, et al. Age-related normograms of serum antimullerian hormone levels in a population of infertile women: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2359–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Giulini S, Traglia M, Argento C, Sala C, et al. Normal serum concentrations of anti-Mullerian hormone in women with regular menstrual cycles. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barad DH, Weghofer A, Gleicher N. Utility of age-specific serum anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weenen C, Laven JS, Von Bergh AR, Cranfield M, Groome NP, Visser JA, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:77–83. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, te Velde ER, Fauser BC, Bancsi LF, de Jong FH, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3065–3071. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo JH, Kim HO, Cha SW, Park CW, Yang KM, Song IO, et al. Age specific serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels in 1,298 Korean women with regular menstruation. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2011;38:93–97. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2011.38.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lekamge DN, Barry M, Kolo M, Lane M, Gilchrist RB, Tremellen KP. Anti-Mullerian hormone as a predictor of IVF outcome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:602–610. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson SM, Yates RW, Lyall H, Jamieson M, Traynor I, Gaudoin M, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone-based approach to controlled ovarian stimulation for assisted conception. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:867–875. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi MH, Yoo JH, Kim HO, Cha SH, Park CW, Yang KM, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels as a predictor of the ovarian response and IVF outcomes. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2011;38:153–158. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2011.38.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemos NA, Arbo E, Scalco R, Weiler E, Rosa V, Cunha-Filho JS. Decreased anti-Mullerian hormone and altered ovarian follicular cohort in infertile patients with mild/minimal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knauff EA, Eijkemans MJ, Lambalk CB, ten Kate-Booij MJ, Hoek A, Beerendonk CC, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B, and antral follicle count in young women with ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:786–792. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falconer H, Sundqvist J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, von Schoultz B, D'Hooghe TM, Fried G. IVF outcome in women with endometriosis in relation to tumour necrosis factor and anti-Mullerian hormone. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18:582–588. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Marca A, Pati M, Orvieto R, Stabile G, Carducci Artenisio A, Volpe A. Serum anti-mullerian hormone levels in women with secondary amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1547–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]