Abstract

Longitudinal data suggest heterogeneity in the long-term course of schizophrenia. It is unclear how older adults with schizophrenia perceive changes in their experience of schizophrenia over the lifespan. We interviewed 32 adults aged 50 years and older diagnosed with schizophrenia (mean duration 35 years) about their perceived changes in the symptoms of schizophrenia and functioning over the lifespan. Interview transcripts were analyzed using grounded theory techniques of coding, consensus, co-occurrence, and comparison. The study was conducted by a research partnership involving a multidisciplinary team of academic researchers, community members, and mental health clients engaged in all aspects of study design, interviewing, and analysis and interpretation of data. Results revealed that, in regard to early course of illness, participants experienced confusion about diagnosis, active psychotic symptoms, and withdrawal/losses in social networks. Thereafter, nearly all participants believed that their symptoms had improved, which they attributed to increased skills in self-management of positive symptoms. In contrast to consistency among participants in describing illness course, there was marked heterogeneity in perceptions about functioning. Some participants were in despair about the discrepancy between their current situations and life goals, others were resigned to remain in supported environments, and others working toward functional attainments and optimistic about the future. In conclusion, middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia believed that their symptoms had improved over their lifespan, yet there was substantial variability among participants in how they perceived their functioning. Functional rehabilitation may need to be tailored to differences in perceptions of capacity for functional improvement.

Keywords: aging, psychosis, disability, qualitative research, quality of life

Introduction

The traditional view of the course of schizophrenia has been that of progressive decline,1 yet cross-sectional and longitudinal studies indicate substantial heterogeneity in the long-term course of schizophrenia.2–6 Collectively, studies of community-dwelling outpatients indicate a surprising degree of stability in cognitive abilities,7–9 with little evidence that cognitive ability declines at a faster rate compared with normal subjects. In addition, symptoms prominent at the onset of the disease may diminish in late adulthood,4,10 and a small subgroup of older adults experience sustained remission from schizophrenia.11 Yet, some subgroups of patients, such as those who are chronically institutionalized, display progressive worsening in cognitive ability, functioning, and are unlikely to attain remission.12 In regard to functioning, cross-sectional studies of age effects in subjective indicators of functioning, such as health-related quality of life (HRQOL), have been inconsistent, with some showing a positive effect of age on mental HRQOL,13 no correlation with age,14,15 or a negative relationship.16,17 Better understanding of the determinants of heterogeneity in how older persons with schizophrenia perceive and adjust to their illnesses may help direct preventive and rehabilitative efforts.

Largely missing from the research described above is the perspective of the older patients themselves about whether and in what ways they recognize changes in their illness over time. Although life chart methods have been used in psychiatric illnesses to specify timing in illness course,18 there are few validated instruments to solicit perceptions of lifespan changes in severe mental illness. For this reason, qualitative methods provide a useful approach to assessing individual perceptions of lifespan course of schizophrenia. However, only one study, to our knowledge, has used qualitative methods to address perspectives on illness course in schizophrenia19 and that study interviewed 6 older women with schizophrenia. The limited number of qualitative studies in older adults with schizophrenia may be due, in part, to concerns about whether the interviewees can provide meaningful information to open-ended queries, especially given concerns about their insight and cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, in 2 previous qualitative studies that addressed different subject matter, we have found that qualitative interviews of older adults with serious mental illness are feasible and informative.20,21

The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of the perspectives of older adults with schizophrenia about if and how their experience of the illness had changed over the lifespan as well as their expectations for the future. The study was conducted by a research partnership involving a multidisciplinary team of academic researchers, community members, and mental health clients engaged in all aspects of designing the study, research interviewing, and analysis and interpretation of data.

Methods

Study Participants

Study participants were recruited from the database of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Advanced Center for Innovation in Services and Intervention Research, that focuses on late-life psychoses, and is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Participants were recruited by informing other Center investigators of the study and through dissemination of study information via Center recruitment staff. A total of 32 individuals were scheduled and interviewed, based on accepted sample size estimates for qualitative research.22,23

A maximum variation sampling procedure was adopted24 to enable diversity in age, gender, ethnicity, and living situation. Moreover, study exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum in order to enroll a diverse sample. The minimum age to participate in the study was 50 years. Participants were excluded if they could not demonstrate capacity to provide informed consent, were currently hospitalized in an inpatient setting or a nursing home, or were experiencing any acute or chronic illness that would substantially diminish their ability to participate in an interview study (eg, if they had been previously diagnosed with dementia). Based on their participation in previous Center research studies, all participants had previously undergone structured diagnostic assessment, and diagnoses of schizophrenia were confirmed by a board-certified psychiatrist or psychologist in consensus meetings. All participants had to consent to audio taping of the interviews and be willing for deidentified portions of the transcripts to be reported in scientific publications. This study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board, and a written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Procedures

After providing informed consent, participants were interviewed at UCSD or at their place of residence, depending on their preference. The meeting consisted of a semistructured interview and a demographic questionnaire.

Interviewers

The interview was developed in collaboration with 2 community members (a consumer [S.S.] and the parent of a consumer [G.H.]) and 2 academic researchers (C.D., M.H.). The community members held leadership roles in the San Diego Affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. All the study team members were involved in designing, conducting interviews, analysis, and interpretation of qualitative data. All interviewers, including community members, attended two 3-h training meetings which covered: (1) the goals of the project, (2) procedures and interviewing techniques, and (3) participant and interviewer safety. They were also taught procedures for obtaining informed consent, introducing ideas to be discussed, moderating the discussion, handling difficult participants, and leading the interview to a conclusion.25

Interview

Based on consensus meetings, a semistructured interview format was developed, and all participants were asked the following questions with follow-up probes as appropriate:

Past: What was it like when you first started experiencing symptoms of schizophrenia?

Changes: How has your view of schizophrenia changed over your lifetime? Do you believe that your condition has changed over time?

Current: How would you describe your life at the moment? Can you tell me about things in your life that make your life better? Are there particular areas in your life that you feel make things difficult?

Future: What are your expectations for the future? If it “all worked out,” what would life be like?

The interviews were designed to be open-ended so that interviewees could elaborate on other areas that they felt were important to describing schizophrenia over their lifespan. We included no specific prompts regarding life domains related to quality of life (eg, finances and medical illnesses) and avoided steering the discussion toward topic areas specified by the interviewer. The average interview lasted between 45 min and 1 h. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Following the semistructured interview, the participants were asked to provide basic demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, education, and living situation) along with the age of onset of symptoms and of diagnosis.

Data Analysis

Audiotapes were transcribed and were processed using the grounded theory-based approach of “coding consensus, co-occurrence, and comparison” described by Dennis et al.26 Transcripts were independently coded by 2 coders (S.S. and C.D.) to develop a typology of responses, which was subsequently developed into a coding scheme covering the key domains identified in the interviews. Initially, codes corresponded to the root questions in the semistructured interview, and segments of text ranging from clauses to paragraphs were assigned codes by independent coders. A consensus meeting was held between coders, and any disagreements in assignment or between codes were resolved to create a final coding scheme. The same units of text could be assigned to multiple codes. Because the aim of the study was to understand the course over time of schizophrenia, all text units were assigned a code corresponding to life domain (eg, living situation and relationships) as well the time frame (ie, prediagnosis, from diagnosis until now, current, changes over time, and future). Three interviews were randomly selected and coded independently by the coders to estimate intercoder reliability. Initially, the percent agreement between coders was 60%, but upon inspection, a large proportion of the disagreements was found to lie in the assignment of time frame, specifically prediagnosis and diagnosis until the present. Once these 2 codes were merged, the percent agreement was 75%, indicating an acceptable degree of concordance between coders.27

Codes from the transcripts were entered into a qualitative software package (QSR NVivo) and arranged in a treelike structure connecting transcript segments grouped into separate categories or “nodes.” These nodes and trees were used to examine the association between different a priori and emergent categories and to identify the existence of new, previously unrecognized categories. The number of times these categories occurred together, either as duplicate codes assigned to the same text or as codes assigned to adjacent texts in the same discussion, was recorded and specific examples of co-occurrence illustrated with transcript texts. Finally, through the process of constantly comparing these categories with one another, the different categories were further condensed into broad themes.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in table 1. The mean age of the sample was 55.7 years (SD = 4.1 years; range 50–72). The sample distribution included 40.6% women and a roughly even distribution of individuals residing independently vs in board and care homes. Median income fell below the poverty line (<$10 000), and only 13.3% of participants were currently employed. Participants had experienced the symptoms of schizophrenia for, on average, 35 years.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 32)

| Range | Mean (SD) or % (n) | |

| Age | 50–72 | 55.7 (4.1) |

| Gender (% female) | — | 40.6% (13) |

| Race/ethnicity | — | |

| Caucasian | 67.7% (22) | |

| African American | 12.9% (4) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9.7% (3) | |

| Other | 9.7% (3) | |

| Education | 8–20 | 13.3 (SD = 27) |

| Living situation | — | |

| Independent living | 56.2% (18) | |

| Board and care facility | 43.8% (14) | |

| Marital status | — | |

| Single, never married | 46.9% (15) | |

| Married | 18.8% (6) | |

| Divorced/separated | 34.4% (11) | |

| Employment status (currently employed) | — | 12.9% (4) |

| Income (median) | — | <$10 000 |

| Age of onset of illness | 3–48 | 20.5 (10.4) |

| Age of first diagnosis | 10–55 | 25.7 (11.1) |

| History of any psychiatric hospitalization | — | 93% (30) |

Qualitative Results

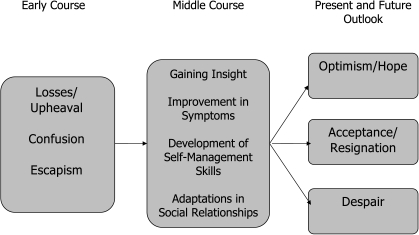

Codes were identified representing life domains as well as the 3 lifespan segments (onset and early course, middle course, current, and future outlook). Using these codes and the constant comparison technique, themes emerged within the sections of the semistructured interview. We assessed these themes with respect to perceived changes over time in the course of illness. Figure 1 summarizes the main themes derived from the interviews.

Fig. 1.

Perceptions of the Course of Schizophrenia Based on Qualitative Interviews (n = 32).

Symptom Onset and Early Course; Upheaval

Participants described the early course of their illness in terms of “feeling different” during childhood, along with chaotic social and family environments (eg, unstable living situations, traumatic experiences, family members with mental illnesses).

“When I was, when I was in Special Ed classes and voices would talk to me a lot, you know, and I'd tell them not to bother me no more. And a couple of times that I did that it disappeared for a few minutes. Then it came back though. And then it was tragic after that.”

“I wanted to stay at home all the time. I didn't want to go out. My dad had to force me to go outside to play with the kids because I was afraid they were going to laugh at me, and make fun of me.”

Losses were frequent—eg, several women were forced to give newborn babies up for adoption, or to relinquish custody of older children, never to see them again. Participants described being confused about the symptoms and public reactions to schizophrenia. “Escapism” was a common response to these troubling situations. This included abusing substances and/or suicide attempts.

“But when you are labeled a schizophrenic or you have psychosis and you don't understand it because you didn't learn about it prior to and you're like, all of a sudden you're in this nightmare, and with nobody to help you because nobody understands, nobody's in it with you. The whole world is dead; you're the only one alive in this big graveyard, which is the world. You have to survive with no money and no place to sleep and all these dead people trying to kill you or whatever, rob you of your sanity is more like it, same thing.”

“I couldn't understand it and that was hard for me and I wanted to commit suicide. Yeah, and I tried. I got in the car once and drove really fast and tried to wreck the car, but then I finally came to my senses that I already had a baby and I didn't want to leave the baby motherless.”

In terms of functional milestones, 15 participants had never married; the remainder reported experiencing significant marital discord, including emotional abuse, fear, and complete family upheaval. Some individuals had been able to manage their illness well enough to pursue a higher education (8 individuals had some college education). Some individuals worked intermittently; a few were able to hold down jobs for months and even years but were forced to quit when their symptoms became unmanageable.

Financial support was undependable and often a function of the individuals' ability to advocate for themselves in their dealings with social services agencies.

“I lived on the streets for quite a couple of years · · · because I didn't know what to do with myself and I ran out of money to live with my mom and stepfather · · · and they kicked me out.”

Early experiences with treatment could be divided into self-initiated or forced, with the latter resulting from pressure from family members or law enforcement. Most participants described a series of trials of different medications, with periods of nonadherence to the medication regimen because of lack of efficacy or side effects.

Middle Course: Adaptations to Symptoms

Participants described a lengthy period of transition after early experiences with schizophrenia, during which there were struggles with hospitalization, finding medications that worked, homelessness or incarceration, family disruptions, and often little or no support of any kind. However, the participants we interviewed described steps they took to adapt to schizophrenia, with most attaining symptom improvement and stable housing (either in a board and care facility or independent housing). The interviewees described gaining insight that helped improve their life situation; eg:

“In '98, I was sitting in the courtyard in the unit I was on. I was smoking my cigarette and I looked up and saw this razor wire and I go, “Is this really what I want?” I'm talking to myself. “I've been here a long time. Am I really going to be here until I die?” I put out my cigarette and went to find my [counselor]. “I told her “I don't want to die here, I don't want to die [here], what can I do?”

Participants chose to take their illness seriously and to become more knowledgeable about it, which included motivation to acquire effective self-management skills.

“I learned to look at myself and do a little self-inventory on myself. I started learning things, and the more I learned, the more it was helpful to me.”

“With the illness, like I say, you know, as long as you're willing and trying to get better, then I'm all for it. But if I wasn't trying to get better or trying to make a life for myself, Lord knows where I'd be right now. Because no one was making me take this medication.”

Nearly all the participants felt that their symptoms became more manageable and less disruptive. The interviewees attributed these improvements to developing better coping abilities, adherence to a stable treatment regimen, and participation in group therapy-related activities. They accepted the need for medications to control their illness and recognized the importance of a collaborative relationship with a doctor whom they could contact when they felt that their symptoms were worsening.

The participants described a number of techniques they used to cope with the voices, including ignoring them, talking back to them and telling them to “shut up,” or using the television or radio to distract their attention.

“Yeah, I was able to change my way of thinking to the point where I can use the intelligence that God gave me to reason my way through this delusion of paranoia, which it is. People who hardly know me aren't going to be talking about me.”

“Every time I pass a group of people · · · I think they're talking about me · · · Then I realize that I'm able to reason my way through it and say, well, wait a minute, it doesn't ring true. Why would they be talking about me?”

Middle Course: Losses in Social Relationships and Adaptations in Social Networks

Most participants described social isolation, whereas a few maintained regular contact with family members or remnants of their social network. With limited opportunities for socialization and the fear of being rejected or discriminated against, they were leery of interacting with people outside familiar environments. The interviewees often worried about displaying symptoms in public.

“I get around and I just isolate myself, because I don't feel most people can understand or relate to what I have to say.”

The majority of individuals reported that they maintained some form of contact with their families, while some individuals had relatives they had not been in touch with for 20–30 years.

“Well, I did have the phone numbers of a lot of relatives in the family, but I sort of feel afraid to call them. I guess I sort of feel embarrassed about my illness, you know.”

However, some families were very supportive. Some moved to be closer to the participant to be able to provide support. A brother regularly refilled the minutes on the participant's cell phone so that they could keep in touch. Moreover, peers had replaced social networks for many participants.

“The people here, we talk, we laugh, we joke, and they're always there for me. If I feel bad, they're always there to help me go through it together. And I think I feel better about myself now than I did when I was a kid.”

Present and Future Outlook

Whereas participants were consistent with each other in regard to their experience of symptom improvement, there were marked differences among participants in their appraisal of the present life situation and their outlook toward the future. We identified 3 subgroups of interviewees in regard to outlook: (a) with despair over lost opportunities (n = 6), (b) with resignation/acceptance of current situation (n = 16), and (c) with hope and optimism (n = 10). There were no significant differences between these groups in age, gender, ethnicity, age of onset, education, or living situation, although the small group sizes likely precluded detection of differences due to low power.

With Despair Over Lost Opportunities.

With increased understanding of their illness, some participants were regretful over their failure to achieve the goals they had once set for themselves.

“I criticize myself for not being smart enough to do certain things or to make more money or to have things that other people have.”

Diagnosed with schizophrenia when he was 17 years, a 52-year-old man described living with his sister (who also had schizophrenia) and their mother until 4 years before the interview when the mother passed away. He described a conversation with his sister:

“I asked her once, ‘Where did we go wrong, why are we in these Board and Care homes? · · · I feel like we're in here because people have given up on us or we've given up on ourselves.' ”

He wondered if receiving Social Security Income (SSI) at an early age had prevented him from doing more for himself:

“I wonder would I have tried to get a job or if getting SSI has kind of lost my will to survive because I'm getting money”. And again, “If I had my own apartment I might have a little more self-esteem. Living here, I feel like I'm here because I can't help myself, like I'm hopeless. That's why they put me here.”

Another 50-year-old man stated: “I feel like I have never lived enough · · · and as I keep going on this just keeps getting worse because I feel like I'm not living up to my expectations of what I thought my life was going to be. And I just, it just keeps getting worse as I get older. I just keep losing.”

With Resignation/Acceptance.

A subset of participants appeared to have accepted their situation, and they no longer compared themselves with “normal” people out in the community but rather to those who were doing worse.

“I have a roof over my head, I have food to eat and clothing and my computer and my stereo, and if I compare my life with some of those starving people in other countries, it's like I'm living in heaven compared to them.” · · · There's always somebody better off or worse off than yourself.

One 61-year-old woman described her current life in a board and care home, “you've got everything you want · · · and meals · · · I can go to bed anytime · · · and be lazy. I don't have to talk · · · I am not in a locked facility.” She said that she missed “going out and doing things,” but chose not to.

Among the greatest barriers to making changes in this subset of participants were their financial limitations.

“I don't think I'm in control of my future. · · · My financial situation controls it. You can only do so much on a limited budget · · · it looks the same every day, month after month.”

“I don't really have long-term goals, not any more. I did at one time.”

With Hope and Optimism.

The third subgroup of participants were hopeful about the future and were attaining functional milestones for the first time in their lives. These individuals took pride in their ability to participate in normal activities.

“It's now, like I say, in remission. I can lead a normal and productive life. I mean, I can do anything anybody else can do, you know? I can drive a car. How I was talking about responsibility, I can open bank accounts, I can get a new cell phone line, and I can function.”

Another interviewee taught a class on symptom management at a youth health center and also worked as a cashier,

“As long as my performance [at work] is ok, I'm fine · · · I never had three things at one time, a job, a car and a house, never. This is the longest I have ever kept a job, almost seven months, longest in my life since I was 23.”

Discussion

The personal interviews we conducted with older adults with schizophrenia revealed a number of aspects of the experience of aging with this illness. Similar to previous cross-sectional and longitudinal reports that indicate improvement in the symptoms of schizophrenia, most of the participants we interviewed believed that the symptoms of schizophrenia, particularly the positive symptoms, were most severe in the early course of the illness and had improved over time. Participants attributed this improvement to their active development of self-management skills, detailing a variety of strategies used to cope with hallucinations and delusions. Interviewees had also made adaptations to social networks, with peers and facility staff replacing family relationships for some. Despite these consistencies among the participants, they differed from one another in their outlook toward the future. The interviewees were either distressed over the discrepancy between their life goals and their situation or resigned to accept their current level of independence and functioning or optimistic about and empowered by functional attainments. Overall, our study suggests that symptom improvement over the lifespan may be characteristic of community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia, yet elements of recovery (eg, optimism and hope) and attainment of functional milestones remain elusive for many.

This study has several limitations. The sample was restricted to middle-aged and older outpatients in one geographic region, all of whom were receiving treatment. Participants needed to be willing and capable of participating in an interview about their experience with schizophrenia, which by nature excluded participants with severe psychotic symptoms and people who did not want to participate in research. Therefore, these results may not generalize to institutionalized or inpatient populations or participants who are too symptomatic or cognitively impaired to participate in interviews. The small sample size made it difficult to compare responses between specific target groups, and there was heterogeneity within the sample. Finally, retrospective narratives about life changes are influenced by the present state of the participant, and it is certainly possible that state factors (eg, depressed mood) influence the recounting of lifespan trajectories.

Nevertheless, we found that all but one of the 32 interviewees described improvement in the personal impact of symptoms of schizophrenia, after experiencing the greatest degree of disruption and symptom severity in the early years of the illness. There are several theoretical explanations that have been proposed for improvement in schizophrenia in later life. It is likely that there is a survivor effect in that older adults with schizophrenia have avoided suicide and other causes of mortality, although long-term follow-up studies indicate that survivor biases may not fully account for cross-sectional differences.3 Normal age-related neurobiological changes, such as reduced activity in the dopaminergic system, may produce attenuation in severity of positive symptoms.9 Older adults may have less substance abuse comorbidity than their younger counterparts.28 Our qualitative study suggests that over the lifespan, individuals attain greater capacity to manage psychotic symptoms. Participants described increasing their acceptance and self-management abilities, which is consistent with the observation that medication adherence appears to be better among older vs younger patients.29 It is notable that the development of these skills was portrayed by participants as an active self-motivated process. It is likewise notable that participants were not free of symptoms, and many continued to experience active hallucinations or delusional thinking, consistent with other literature suggesting that maintenance of employment is possible even in the presence of positive symptoms.30 However, they were more able to engage in strategies that defused the impact of psychosis (eg, challenging the reasoning underlying paranoia), consistent with skills taught in cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia.31 Therefore, many older people appeared to have successfully adapted to the symptoms of schizophrenia, and, in addition, some had adapted social networks to include peers and staff members to compensate for losses in indigenous social networks (although there may be a role for interventions aimed at strengthening indigenous social networks).

However, while the impact of the symptoms of the illness appear to lessen into older age, trajectories of functional recovery do not always follow this general pattern of improvement.32,33 Our qualitative study provides insight into potentially important psychological mechanisms that may accompany functional recovery. There is not general agreement concerning the definition of recovery,34 and it can be seen as a process or an outcome; however, a U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration Consensus Statement definition of recovery is: “living a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential.”35 In light of this definition, there were 3 patterns among interviewed participants. One participant subgroup expressed hopelessness in expectations about the future, despaired over lost opportunities over the lifespan, and experienced a significant discrepancy between their goals for the future and their current situation. As middle-aged and older adults, these individuals felt that they were “running out of time” to make functional improvements (eg, getting married). This subgroup may benefit from interventions and/or peer support centering on setting obtainable goals and reducing depressogenic cognitions such as self-blame. A second subgroup expressed a general resignation to their situation, expecting to stay in supported housing environments for the remainder of their lives, lacking a sense of control of their future, citing financial barriers to change. This group may benefit from education in ways in which they could overcome financial barriers,36 such as the Social Security Administration's “Return to Work” program. Finally, a third subgroup of interviewees, who were hopeful about the future, described the new experience of attaining long-term goals (eg, employment) that had been long derailed by schizophrenia. Future studies should examine the experiences and practices of such people in order to determine how they managed to positively alter their life trajectories toward recovery. In sum, our qualitative study suggests that even if individuals learn to manage schizophrenia over its long-term course, only a proportion of them experience commensurate improvements in their capacity to attain functional recovery. In addition to the need to refocus interventions toward impacting functioning,37 this study suggests that different rehabilitative strategies may be needed to improve functional outcomes among people who do not believe they have the capacity to make functional changes vs those who are working toward functional change but believe they are failing at it. Finally, heterogeneity in the course of schizophrenia in regard to symptoms and functioning likely increases with age, as with increasing heterogeneity among unaffected people in many traits, and the divergence in perspectives on the future is consistent with increasing heterogeneity.

There were advantages in conducting this study with a community-based collaboration in which mental health consumers were involved in all phases of the study.38Community members volunteered a great deal of time and energy, and the study was accomplished with a minimal budget. Some aspects of the development and adaptation to a chronic illness are universal, and the perspectives of consumers were essential in developing the interview and extracting meaningful themes from participants during interviews and from transcripts. On balance, there is a need for enhanced interviewer training/support, in that the content of interviews was emotionally difficult for some consumer interviewers, and a formal support system should be established.

Compared with 1961, when sociologist Erving Goffman who interviewed residents of locked mental health facilities wrote “The application of stringent restrictions on self-expression and behavior, along with the threat of punishment, denied residents the opportunity to develop an independent sense of self,”39 the participants in our study were no longer subject to that degree of control. The interviewees appeared to have benefited from the system of care to the extent that they experienced subjective improvements in symptoms and some areas of functioning, which may provide hope for younger adults as they anticipate growing older with schizophrenia. Nevertheless, there was significant heterogeneity in terms of recovery, with different personal trajectories toward or away from recovery that may require tailored approaches to functional rehabilitation. New psychosocial or policy-based approaches are needed to ensure that more people with schizophrenia experience a long-term course toward both symptom reduction and recovery.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health grants K23MH077225 and P30MH066248.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures of Conflict of Interest: D.J. is the Principal Investigator of an National Institute of Mental Health-funded grant for which antipsychotic drugs are donated by AstraZeneca, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. None of the other authors have any disclosures of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians. Vol 2. Canton, MA: Science History Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding CM. Course types in schizophrenia: an analysis of European and American studies. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:633–643. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding CM, Zubin J, Strauss JS. Chronicity in schizophrenia: revisited. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1992;8:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleule M. The long-term course of the schizophrenic psychoses. Psychol Med. 1974;4:244–254. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700042926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen C, editor. Schizophrenia into Later Life. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey PD, editor. Schizophrenia in Late Life: Aging Effects on Symptoms and Course of Illness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer B, McLure F, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in late life: findings challenge traditional concepts. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9(2):51–58. doi: 10.1080/10673220127883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeSisto M, Harding CM, McCormick RV, Ashikaga T, Brooks GW. The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness. II. Longitudinal course comparisons. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:338–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeste DV, Twamley E, Eyler LT, Golshan S, Patteron T, Palmer B. Aging and outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:336–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Sustained remission of schizophrenia among community-dwelling older outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1490–1493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Mohamed S, Kennedy J, Brickman A. Stability of cognitive performance in older patients with schizophrenia: an 8-week test-retest study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):110–117. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folsom DP, Depp C, Palmer BW, et al. Physical and mental health-related quality of life among older people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sciolla A, Patteron T, Wetherell J, McAdams L, Jeste DV. Functioning and well-being of middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia: measurement with the 36-item short-form (SF-36) health survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:629–637. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.11.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bankole AO, Cohen CI, Vahia I, Diwan S, Kehn M, Ramirez PM. Factors affecting quality of life in a multiracial sample of older persons with schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:1015–1023. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31805d8572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM. A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophr Res. 1997;27(2–3):181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartels SJ. Improving system of care for older adults with mental illness in the United States. Findings and recommendations for the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:486–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding CM, McCormick RV, Strauss JS, Ashikaga T, Brooks GW. Computerised life chart methods to map domains of function and illustrate patterns of interactions in the long-term course trajectories of patients who once met the criteria for DSM-III schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;5:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pentland W, Miscio G, Eastabrook S, Krupa T. Aging women with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2003;26:290–302. doi: 10.2975/26.2003.290.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Perceptions of problems and needs for service among middle-aged and elderly outpatients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Community Ment Health J. 2002;38:391–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1019808412017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palinkas LA, Criado V, Fuentes D, et al. Unmet needs for services for older adults with mental illness: comparison of views of different stakeholder groups. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:530–540. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180381505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles M, Hubermman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss M, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Senzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard H. Qualitative Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennis GW, Best JA, Taylor DW, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 1990;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson TL, Jeste DV. The potential impact of the baby-boom generation on substance abuse among elderly persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al. Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Med Care. 2002;40:630–639. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell K, Bond GR, Drake RE. Who benefits from supported employment: a meta-analytic study. Schizophr Bull. 2011 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp066. 37:370–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:520–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey PD. Functional recovery in schizophrenia: raising the bar for outcomes in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:299. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schooler NR. Relapse prevention and recovery in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 5):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellack AS. Scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: concordance, contrasts, and implications. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:432–442. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services; National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery. http://mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/publications/allpubs/sma05-4129/. Accessed April 2, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drake RE, Skinner JS, Bond GR, Goldman HH. Social security and mental illness: reducing disability with supported employment. Health Aff. 2009;28:761–770. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kern RS, Glynn SM, Horan WP, Marder SR. Psychosocial treatments to promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:347–361. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson L, Ridgway P, Schmutte T, O'Connell M. Purposes and goals of service user involvement in mental health research. In: Wallcraft J, Schrank B, Amering M, editors. Handbook of Service User Involvement in Mental Health Research. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goffman E. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York, NY: Anchor Books; 1961. [Google Scholar]