Abstract

Two reasoning biases, jumping to conclusions (JTC) and belief inflexibility, have been found to be associated with delusions. We examined these biases and their relationship with delusional conviction in a longitudinal cohort of people with schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis. We hypothesized that JTC, lack of belief flexibility, and delusional conviction would form distinct factors, and that JTC and lack of belief flexibility would predict less change in delusional conviction over time. Two hundred seventy-three patients with delusions were assessed over twelve months of a treatment trial (Garety et al., 2008). Forty-one percent of the sample had 100% conviction in their delusions, 50% showed a JTC bias, and 50%–75% showed a lack of belief flexibility. Delusional conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility formed distinct factors although conviction was negatively correlated with belief flexibility. Conviction declined slightly over the year in this established psychosis group, whereas the reasoning biases were stable. There was little evidence that reasoning predicted the slight decline in conviction. The degree to which people believe their delusions, their ability to think that they may be mistaken and to consider alternative explanations, and their hastiness in decision making are three distinct processes although belief flexibility and conviction are related. In this established psychosis sample, reasoning biases changed little in response to medication or psychological therapy. Required now is examination of these processes in psychosis groups where there is greater change in delusion conviction, as well as tests of the effects on delusions when these reasoning biases are specifically targeted.

Keywords: delusions, reasoning, jumping to conclusions, belief flexibility, psychosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) defines delusion as “A false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly sustained despite what almost everyone else believes and despite what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the contrary” (p. 765). Thus, a delusional belief is incorrect; it is based on erroneous judgments about the world, and it is unresponsive to countervailing evidence. Biases of reasoning have been invoked to understand the process of delusion formation, and limited data-gathering (jumping to conclusions; JTC) and a failure to think of alternative accounts to the delusion (a lack of belief flexibility) have previously been shown to be related to how strongly a delusion is held (delusional conviction; e.g., Freeman et al., 2004; Garety et al., 2005). In this study, the single largest study of its type, we wanted to (a) examine the prevalence of the reasoning biases JTC and lack of belief flexibility in individuals with delusions; (b) evaluate the structure of delusional conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility and whether they are distinct processes; and (c) assess whether delusional conviction would vary in response to levels of JTC bias and belief flexibility.

Reasoning Processes Associated With Delusions

The most replicated reasoning bias in delusion research is JTC, a tendency to gather less data than controls to reach a decision (reviewed by Fine et al., 2007; Garety & Freeman, 1999; Freeman, 2007). Limited decision-making encourages the rapid acceptance of erroneous beliefs. Research published so far has involved relatively small numbers of participants, with JTC being apparent in between one third and two thirds of individuals with delusions (e.g., Garety, Hemley, & Wessely, 1991, 2005; Moritz & Woodward, 2005; Startup, Freeman, & Garety, 2008; van Dael et al., 2006). It has also been reported in people “at risk” for psychosis (Broome et al., 2007), and, to an attenuated degree, in the relatives of people with psychosis and in people scoring highly on delusional ideation scales (e.g., Colbert & Peters, 2002; Freeman, Pugh, & Garety, 2008; van Dael et al., 2006; Warman & Martin, 2006). In cross-sectional studies, it is greatest in patients with current delusions (e.g., Lincoln, Ziegler, Mehl, & Rief, 2010; van Dael et al., 2006). There have been few longitudinal investigations of JTC: In a systematic review (So, Garety, Peters, & Kapur, 2010), three such studies are reported (Peters & Garety, 2006; Menon, Mizrahi, & Kapur, 2008 and Woodward, Munz, LeClerc, & Lecomte, 2009). The available data show that JTC does not improve consistently over time or with symptom improvement, but there is some evidence that baseline JTC predicts outcome. For example, JTC was shown to moderate the response to antipsychotic treatments in a drug-naïve group of patients with a first episode of psychosis: Those with an extreme JTC bias showed a poorer treatment response (Menon et al., 2008). Taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that it is likely that JTC is a relatively stable trait increasing susceptibility to the development of delusions, and it may predict change over time.

Belief flexibility in psychosis refers to “a metacognitive process about thinking about one's own delusional beliefs, changing them in the light of reflection and evidence and generating and considering alternatives” (Garety et al., 2005, p. 374). It has been assessed with the Possibility of Being Mistaken (PM) and Reaction to Hypothetical Contradiction (RTHC) items of the Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule (MADS; Wessely et al., 1993). These items assess, in the context of an interview about delusional beliefs, whether the individual can consider it “at all possible” that they might be mistaken in their belief, however unlikely, and also to consider a hypothetical but plausible piece of evidence that might counteract their belief. We have since developed a further item which we also consider to tap belief flexibility, in the Explanation of Experiences assessment (Freeman et al., 2004). In this, persons with delusions are asked if they can think of any possible alternative explanation (AE) for the evidence they cite in support of their delusion, other than the delusional explanation. Contrary to the traditional view of delusions as fixed and unresponsive to countervailing evidence, approximately one quarter to one half of individuals with delusions demonstrate belief flexibility on any one of these assessments (e.g., Freeman et al., 2004; Colbert, Peters, & Garety, 2010; Buchanan et al., 1993). For example, Garety et al. (2005) found that half of those with delusions acknowledged that there was a possibility that they were mistaken, while Freeman et al. (2004) reported that a quarter of individuals with delusions could generate alternative explanations for their experiences even if they did not agree with them. There have been no longitudinal studies of belief flexibility measured in this way although, in one study, we found evidence of improvement over time in evidence evaluation, suggesting that belief flexibility may change as delusions remit (So et al., 2010). There is also some evidence that it might predict change. Flexibility, as assessed by the PM item, predicted successful response to psychological therapy for psychosis in a randomized, controlled trial (Garety et al., 1997). We, therefore, hypothesized that change in delusions may be facilitated by a willingness to consider that a delusion may be mistaken and that alternative explanations might be possible. It has further been argued that JTC influences delusional conviction via a lack of belief flexibility (Garety et al., 2005). Limited data-gathering (JTC) may preclude the consideration of alternative explanations (belief flexibility), and therefore, strengthen belief in a delusional account. In our cognitive model of psychosis, we propose that, in common with cognitive models for other disorders, appraisals are key to the development and persistence of psychosis. We argue that reasoning biases, such as JTC and a lack of belief flexibility, are important in that they may influence the appraisal of anomalous experiences, adverse events, and distressing emotions (by limited data gathering or generation of alternatives), and thus, contribute to symptom formation and maintenance (Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman, & Bebbington, 2001; Garety, Bebbington, Fowler, Freeman, & Kuipers, 2007).

The Measurement of Delusion Conviction and Reasoning Processes

Both limited data-gathering and less belief flexibility have been shown to be associated with stronger delusional conviction (e.g., Colbert et al., 2010; Freeman et al., 2004, 2008; Garety et al., 2005). However, this raises the issue of whether these concepts are truly distinguishable from delusional conviction. This is especially so for the concept of belief flexibility, where people need to acknowledge that they could be mistaken about their delusional belief, even if they think this is highly unlikely. In other words, is belief flexibility simply an indirect measure of delusional conviction? To our knowledge, only one study has formally examined belief flexibility in people with delusions by using nondelusional, neutral material—in this case, the belief that “the sun will rise tomorrow, that is, that there will be another day tomorrow” (Colbert et al., 2010). In this study, delusional participants showed less willingness than a nonclinical control group to consider that they might be mistaken on this standard “neutral” belief, suggesting that a lack of belief flexibility may be characteristic of the reasoning style of people with delusions rather than being restricted to and confounded by their conviction in their delusional beliefs. However, further examination of this is clearly warranted.

The measurement of these concepts is, therefore, key to further investigation. A variety of measures have been used to assess delusional conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility. Standard psychiatric assessments—the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1984)—have typically been used to assess delusions, with conviction as an important scoring criterion. Conviction has been measured using multidimensional scales, including the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS) (Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier, & Faragher, 1999), the MADS (Wessely et al., 1993), and the Explanations of Experiences interview (EoE) (Freeman et al., 2004). Most studies of delusional conviction have used single measures. While these measures are likely to be highly correlated, we do not know how effectively they capture the degree of belief conviction. A similar situation applies to the measurement of reasoning biases. The probabilistic reasoning task used to assess JTC has easy and difficult versions, and the content of the task also varies (e.g., Dudley, John, Young, & Over, 1997a). Belief flexibility has been measured variously with assessment of the possibility of being mistaken (PM) (Wessely et al., 1993), the reaction to hypothetical contradiction (RTHC: Wessely et al., 1993), and the generation of alternative explanations (AE: Freeman et al., 2004). There has been no formal investigation of whether these represent aspects of a common reasoning bias or of how they are related to JTC.

The Current Study

Multivariate approaches, such as structural equation modeling and factor analysis, allow exploitation of the richness of multiple measurements and direct investigation of the relationships between latent constructs, controlling for the effects of measurement error in the observed responses (Bentler, 1980). Our current understanding of delusional conviction and reasoning biases in psychosis clearly lends itself to the establishment of latent factors drawn from different instruments relating to similar constructs. For example, Bentall et al. (2009) recently used structural equation models with latent variables to determine the structure of relationships among psychological mechanisms potentially contributing to paranoia which found that both cognitive (including JTC) and emotion-related processes were related to paranoia. In the present study, we analyzed data from the Psychological Prevention of Relapse in Psychosis Trial (Garety et al., 2008), in which patients with a recent relapse of psychosis were assessed at different time points, on multiple measures of delusional conviction, JTC and belief flexibility. Two earlier cross-sectional studies (Freeman et al., 2004; Garety et al., 2005) drew from the first 100 participants in this trial. As discussed in those two studies, it was our a priori plan to replicate the cross-sectional findings in the larger sample reported here and to examine changes over time. In the current study, we aimed first to examine the prevalence of JTC and of a lack of belief flexibility in this group of currently deluded patients following a recent relapse, and then to test hypotheses about their relationships with each other and with delusional conviction over time.

The three hypotheses derived from our review of the literature were as follows:

Delusional conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility are distinct but interrelated processes.

Conviction and a lack of belief flexibility will decline over time, whereas JTC is relatively stable.

Baseline JTC and lack of belief flexibility will predict persistence of delusional conviction over time.

Method

Participants

Participants were 301 patients from the Psychological Prevention of Relapse in Psychosis (PRP) Trial (ISRCTN83557988). Participants were recruited by approaching consecutive patients who had recently relapsed, whether or not they had been admitted. Two hundred seventy-three of the participants had presentations that included delusions; 28 had hallucinations but no delusions. The PRP Trial was a multicenter randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and family intervention for psychosis that took place in the United Kingdom (Garety et al., 2008). It was designed to answer questions both about outcome and the psychological processes associated with psychosis over time. Inclusion criteria for the PRP Trial were the following: a current diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis (schizophrenia, schizoaffective psychosis, delusional disorder), age between 18 and 65 years, a second or subsequent episode starting not more than 3 months before consent to enter the trial, and a rating of at least 4 (moderate severity) on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) on at least one positive psychotic symptom at the time of the first meeting. Exclusion criteria were a primary diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependency, organic syndrome or learning disability, an inadequate command of English, and unstable residential arrangements. Patients were randomized into the following conditions: treatment as usual, treatment as usual plus CBT, and treatment as usual plus family intervention. In this treatment trial, in which CBT and family intervention were investigated and compared with treatment as usual, there were no significant treatment effects on delusional outcomes or other psychotic symptoms, or on JTC and belief flexibility: only depression improved in response to CBT (Garety et al., 2008). The whole sample was, therefore, grouped together in the current study. This report uses symptom and psychological assessments carried out at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months.

Measures

General psychopathology and delusions

Several clinical rating scales were used as measures of psychopathology. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) is a 30-item rating scale developed for assessing phenomena associated with schizophrenia. Symptoms are rated over the past week. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1984) is a 35-item rating instrument. Symptoms are rated over the past month. The Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS) (Haddock et al., 1999) is a 17-item scale measuring multiple dimensions of auditory hallucinations and delusions. Symptoms are rated over the past week. Good psychometric properties have been reported for PANSS (e.g., Kay, 1990), SAPS (Andreasen, 1984; Kay, 1990), and PSYRATS (Haddock et al., 1999). Four scale items were selected to derive the delusional conviction factor: the PANSS delusion item, the SAPS global delusion item, the PSYRATS delusional conviction item, and the conviction score (0–100%) on the EoE (Freeman et al., 2004).

Jumping to conclusions (JTC)

In this study, three versions of the beads task were used. In the first version, individuals are presented with two jars, each containing 100 colored beads. One of the jars contains 85 beads of color A and 15 beads of color B, while the other jar contains 85 beads of color B and 15 beads of color A. Participants are told that the jars will be hidden from view and then beads will be drawn, one at a time, from just one of the jars, and will be replaced in the same jar, so that the proportions remain the same. They can see as many beads as they like before deciding which of the jars the beads are drawn from. The current study also included a more difficult version with beads in the ratio 60:40 (Dudley, John, Young, & Over, 1997b), and a version using salient words (positive and negative) in the ratio 60:40 (Dudley et al., 1997a). In the salient version of the task, the beads are replaced by words ostensibly generated by a survey of the opinions of two groups of 100 about an individual. Participants are told that one group makes 60 positive comments and 40 negative comments, while the reverse is true for the other group. They have to decide which survey the words have been selected from. The variable is the number of pieces of information the participant selects before making a decision. In order to identify people with an extreme reasoning bias, the JTC bias has been defined as making a decision with two pieces of information or fewer (Garety et al., 2005). We have previously adopted this categorical (dichotomous) method of assessing JTC (Garety et al., 2005) since, first, evidence suggests that it is the extreme bias, of gathering very limited data, which particularly characterizes people with delusions (Garety et al., 1991) and, second, the alternative method employed by researchers, the number of draws to decision, is not a normally distributed continuous scale since the information value of each additional bead varies according to the color of the bead presented and the sequence employed. However, we explored the use of both scoring methods in our factor analyses (see below).

Belief flexibility

The Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Scale (MADS; Wessely et al., 1993) is a standardized interview that assesses eight dimensions of delusional experience. The belief maintenance section of the MADS inquires about the evidence for the delusion, and two of its items have been used to measure aspects of belief flexibility (the possibility of being mistaken, PM, and the reaction to hypothetical contradiction, RTHC). The evidence for the delusion cited by participants is sensitively discussed, and they are asked whether it is at all possible for them to be mistaken about their delusional belief. The interviewer then asks how they would react in a hypothetical situation if some new evidence were to be generated which contradicts the delusion. If they report that this would alter in any way their level of belief, this is recorded as belief flexibility, each item dichotomously scored (yes/no). The scale has very good interrater reliability (Wessely et al., 1993), and kappas for these two items are reported as excellent (PM kappa = 0.91 and RTHC kappa = 0.90).

The EoE (Freeman et al., 2004) is a structured interview designed to assess whether people can envisage alternative explanations for the evidence cited for their delusion. Once the evidence for the delusion is established, they are asked, “Can you think of any other explanations for the experiences that you have described? Are there any other reasons—other than [the delusional belief]—that could possibly account for these experiences even if you think they are very unlikely?” The generation of any alternative explanation (scored yes/no) is taken as a measure of belief flexibility. The current strength of the delusional explanation is rated on a conviction rating scale, “How strongly do you believe X?” (0–100%), which forms one of the conviction measures in the current study. Since this item is so similar to the MADS item, “How sure are you about X?” the MADS conviction item was not included in the assessment battery.

Interrater Reliability of Clinical Assessments

All assessments were conducted by research workers after consent had been obtained. Interviews were tape-recorded for reliability and quality control purposes. Research workers met regularly with a supervisor throughout the study to maintain reliability of procedures and ratings. Reliability of clinical interview ratings was assessed using the PANSS positive symptom score. At least one other assessor (selected from a panel of 15 raters—excluding the rater responsible for the initial assessment) rerated 55 assessments. The number of reratings varied between 1 and 6, and the total number of ratings made by the 15 raters varied between 2 and 27. A linear one-way random effects model (with participant identification as the explanatory factor) was fitted by restricted maximum likelihood using Stata's xtreg procedure (version 8 for Windows) and yielded an intraclass correlation of 0.88 (95% CI 0.82–0.92). This indicates very acceptable interrater reliability. We also checked the reliability of ratings of the PSYRATS. The PSYRATS conviction rating simply requires the assessor to categorize the patient's percentage response into one of five ordinal categories defined by percentage numbers. There is no clinical judgment required, and interrater variability would not be expected. In the development of the scale, six assessors each rerated six interviews and there was perfect reliability for the delusion conviction item (Haddock et al., 1999). In the current study, seven PSYRATS interviews were rerated, and again there was perfect reliability.

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive reports of the frequency of individual measures of reasoning biases (JTC and belief flexibility) and of levels of conviction, and their associations with each other, were generated with SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, 2006).

For the first hypothesis, that conviction, JTC and belief flexibility are distinct but interrelated processes, both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) to identify and confirm the structure of conviction and reasoning biases. In order to establish the factor structure of conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility, baseline measures of these variables were entered into an exploratory factor analysis (using data only from the 273 patients with delusions). The measures (“items”) entered into the factor analysis were specified in Mplus as being either quantitative (the default) or categorical. For conviction, the following quantitative measures were used: PANSS delusion item (range 1–7), SAPS global delusion item (range 0–5), PSYRATS conviction item (range 0–4), and conviction score on the EoE interview (range 0–100). The categorical (dichotomous) JTC measures were presence/absence of JTC bias on the 3 versions of the beads task, and the continuous measure of JTC, which we also explored, was number of beads/words drawn. For belief flexibility, binary (positive/negative) responses to the “possibility of being mistaken” and “reaction to hypothetical contradiction” items in the MADS interview and the “generation of alternative explanations” item in the EoE interview were entered. A higher JTC factor score indicated a more limited data-gathering style, whereas a high belief flexiblity factor score meant greater belief flexibility. In exploratory factor analysis, all loadings were freely estimated, but the variances of each of the factors were constrained to be 1.

To test the second hypothesis, concerning change over time, for each of the constructs (conviction, JTC, and belief flexilibity), a longitudinal (repeated measures) factor analysis model was separately fitted. At each of the three time points, we specified the same underlying factor. For each time point, the loading for the first variable entered into the model was set to 1 (to determine the scale). The loadings of each of the other variables (items) were freely estimated but were constrained to be the same across time points (after first establishing that these constraints did not lead to any significant loss of fit). No constraints were imposed on any of the residual (error) variances. Temporal trends in the factor scores were estimated and tested using two orthogonal contrasts created by the “model constraint” option in Mplus—(a) C1: the difference between 3 and 12 month scores, and (b) C2: the difference between the baseline score and the average of the 3 and 12 months scores. An equivalent (global) test of trends was generated by constraining the factor scores to be equal for the three time points and comparing the chi-squares for the constrained and unconstrained models.

The third and final hypothesis was that change in conviction is predicted by JTC and belief flexbility. The same estimated factor scores were correlated with change scores for delusional conviction.

As in most longitudinal studies, there were missing data in this sample. The sample size available for each variable at each time point is specified in Table 1 (for the delusion conviction variables) and the results section (for reasoning variables); descriptive statistics based on these sample sizes are reported. The exploratory factor model was estimated using all available data on the component variables at baseline. The percentages of missing values in the sample (N = 273) on the key variables at baseline are as follows: 0% (PANSS delusion score), 0% (SAPS global delusion score), 1.8% (PSYRATS conviction), 25.3% (EoE conviction), 31.5% (85:15 beads task), 32.6% (60:40 beads task), 34.8% (words task), 20.9% (possibility of being mistaken), 24.9% (reaction to hypothetical contradiction), 24.9% (alternative explanations). Mplus uses maximum likelihood (ML) estimator for continuous variables (e.g., conviction measures) and WLSMV estimator (weighted least-squares with mean and variance adjustment) for categorical variables (i.e., JTC and belief flexibility measures). ML imputes the model parameters using all available data even for cases with some missing responses, whereas WLSMV considers all available data for each pair of variables when estimating the sample statistics. There are, therefore, fewer missing values for the factors than for raw scores: 0% (conviction factor), 13.6% (JTC factor), and 14.7% (belief flexibility factor).

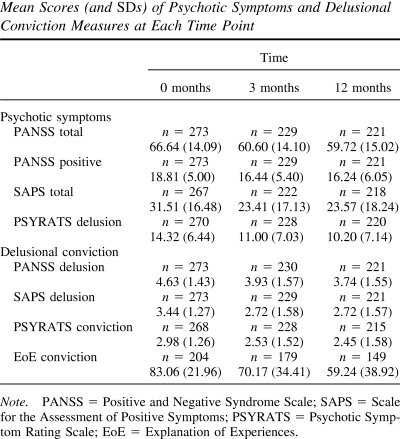

Table 1. Mean Scores (and SDs) of Psychotic Symptoms and Delusional Conviction Measures at Each Time Point.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Data

A total of 273 patients with delusions were included in this study. Seventy percent (n = 193) of the sample was male, and the mean age was 37.7 years (range 19 to 65). The sample was drawn from the following ethnic groups: White (72.2%), Black African (9.2%), Black Caribbean (7.3%), Black other (2.2%), Indian (1.8%), and other (7.3%). The major psychiatric diagnoses were schizophrenia (85.0%), schizoaffective disorder (13.6%), and delusional disorder (1.6%). They had an average length of illness of 10.78 years (SD = 8.96, range 0–44 years). The mean scores for the psychotic symptom measures at baseline and at the follow-ups are shown in Table 1, and they indicate a moderately high level of psychotic symptoms.

At baseline, 110 (41%) participants with delusions had 100% conviction in their belief, 109 (40.7%) held the delusion with conviction between 50 and 99%, and 49 (18.2%) participants had less than 50% conviction in their delusion. The percentages of the sample (n = 273) rated 3 (moderate) or above on the SAPS for each subtype of delusions were as follows: persecutory delusions (57.5%), delusions of reference (55.6%), grandiose delusions (24.2%), delusions of mind reading (23.5%), religious delusions (17.6%), somatic delusions (17.2%), thought insertion (13.5%), delusions of being controlled (12.9%), thought withdrawal (12.8%), thought broadcasting (10.6%), delusions of guilt or sin (8.4%), and delusions of jealousy (1.8%).

Reasoning biases were common. The percentages of participants who jumped to conclusions on the 85:15 beads task at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months were 52.4% (n = 98 out of 187), 61.8% (n = 89 out of 144), and 55.0% (n = 82 out of 149), respectively. The equivalent values for the 60:40 beads task were 40.2% (n = 74 out of 184), 44.4% (n = 64 out of 144), and 41.2% (n = 61 out of 148), respectively. The percentages for the 60:40 words task were 38.2% (n = 68 out of 178), 43.6% (n = 61 out of 140), and 41.9% (n = 62 out of 148).

The percentages of participants who thought it was impossible that they could be mistaken about their belief at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months were 49.5% (n = 107 out of 216), 43.6% (n = 78 out of 179), and 42.6% (n = 66 out of 155), respectively. The percentages of participants who reacted negatively to the hypothetical contradiction (i.e., not allowing a potential decrease in conviction if the hypothetical event were to occur) at the three time points were: 67.3% (n = 138 out of 205), 56.3% (n = 94 out of 167) and 46.2% (n = 66 out of 143). The percentages of individuals who did not give alternative explanations for their belief were 76.1% (n = 156 out of 205), 73.9% (n = 133 out of 180) and 70.7% (n = 106 out of 150).

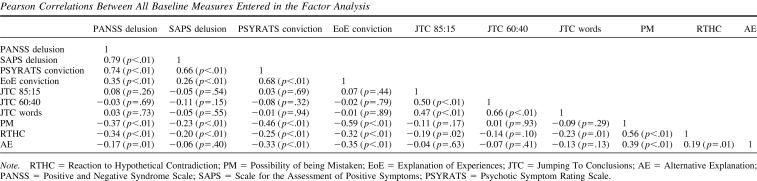

The relationships between the individual measures at baseline are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the measures of conviction are all highly significantly correlated with each other although, unsurprisingly, the conviction rating from the EoE assessment has a relatively weaker relationship with the PANSS and the SAPS measures. There is no evidence of a relationship between the individual indicators of conviction with JTC measures, while there is evidence that higher conviction is associated with less belief flexibility. It can also be seen that the individual indicators of JTC are all highly significantly related to each other, as are those of belief flexibility; however, it is clear that the relationships between the individual measures of JTC with measures of belief flexibility are generally not significantly related, with the exception of significant relationships between two of the indicators of JTC with RTHC.

Table 2. Pearson Correlations Between All Baseline Measures Entered in the Factor Analysis.

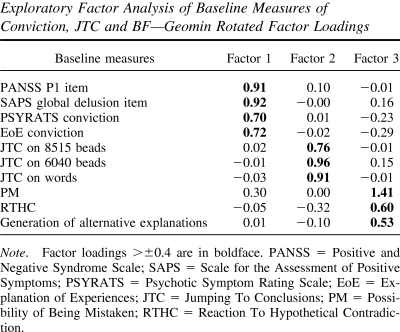

Hypothesis 1: Delusional Conviction, JTC and Belief Flexibility Are Distinct but Interrelated Processes

Exploratory factor analysis was performed on the four measures of conviction, the three measures of JTC, and the three measures of belief flexibility. (For JTC, we initially performed the EFA using both our preferred dichotomous method of scoring (JTC: 2 beads or fewer; no JTC: over 2 beads) and a continuous measure (number of beads drawn), but found that the dichotomous scoring method resulted in a better chi-square test of model fit. We have, therefore, used the factors from the dichotomous scoring of JTC in all the following analyses.) As shown in Table 3, a three-factor model fitted the data best. Moreover, the factor loadings shown in Table 4 indicate that the three factors clearly represent delusional conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility, respectively.

Table 3. Comparison of 1-, 2-, and 3-Factor Models.

Table 4. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Baseline Measures of Conviction, JTC and BF—Geomin Rotated Factor Loadings.

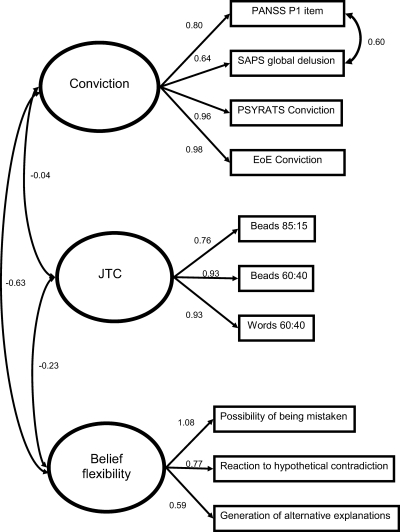

For the conviction factor, since the PSYRATS and EoE items are specific measures of delusional conviction but the PANSS delusion item and the SAPS global delusion score are measures that combine several dimensions of delusional experience along with conviction, the residuals of the last two items were set to be correlated in the factor model, so that the resultant factor reflected level of delusional conviction. The model fit indices showed that the conviction factor model with correlated residuals was a better fit than the model without the correlations (see Table 5). Confirmatory factor analysis was then performed on the baseline conviction and reasoning bias variables. Figure 1 shows the new structure of the three factors with standardized estimates of factor loadings and correlations between factors.

Table 5. Comparison of Measurement Models On Baseline Conviction.

Figure 1. Final factor structure and loadings (standardized estimates) of conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility following confirmatory factor analysis.

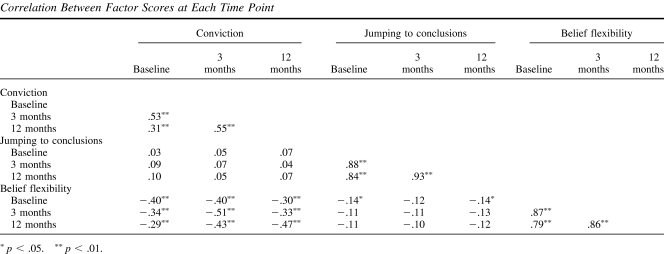

Based on the structure of the three factors, factor scores across time points were estimated using longitudinal factor analysis models for each of the three concepts separately. The mean factor scores for each factor at the three time points were as follows: (a) Conviction (n = 273), 4.64, SD = 1.10; 3.91, SD = 1.21; 3.73, SD = 1.18; (b) JTC (n = 236), 0.17, SD = 1.04; 0.61, SD = 1.03; 0.29, SD = 1.28; and (c) belief flexibility (n = 233), 0.08, SD = 1.70; 0.40, SD = 1.55; 0.60, SD = 2.04. Correlations between the estimated factor scores at each time point are shown in Table 6. There are very strong correlations within the JTC and belief flexibility factors across time points, consistent with their being stable over time, whereas the correlations within the conviction factor over time, while significant, are lower, indicating less stability (see below). Conviction factor scores are correlated with belief flexibility factor scores at all time points (i.e., greater conviction is associated with less belief flexibility), but not with JTC factor scores at any time point. There is a weak correlation between belief flexibility factor score at baseline and JTC factor scores at baseline and 12 months (i.e., greater JTC bias is associated with less belief flexibility; see Table 6).

Table 6. Correlation Between Factor Scores at Each Time Point.

Hypothesis 2: Conviction and a Lack of Belief Flexibility Will Decline Over Time, Whereas JTC Is Relatively Stable

Changes in factor scores over time were analyzed by creating two contrast parameters in the longitudinal factor analysis models: (1) the contrast between factor means at 3 months and 12 months; and (2) the contrast between baseline factor mean and the average of 3 months and 12 months. Tests of contrasts showed that there was no significant change in the conviction factor score between 3 and 12 months, mean change 0.19, SE 0.12, p = .12, but that there was a highly significant change between baseline and the average of the two follow-up values, mean change 0.81, SE 0.10, p < .01. In this case, the equality constraints for the factor loadings over time were not supported by the data. This had practically no effect on the conclusions, however: mean factor change between 3 and 12 months 0.19, SE 0.12, p = .12, and the mean change between baseline and the average of 3 and 12 months 0.81, SE 0.10, p < .01. However, note that although the model with time-varying factor loadings fitted reasonably well according to the CFI (0.97) and RMSEA (0.08) criteria, the fit was not good according to the chi-square value (135.73 with 48 degrees of freedom). On the PSYRATS, 38.4% of the sample showed a decrease in delusional conviction, 42.7% showed no change, and 18.9% showed an increase over the year of follow-up. A third (34.4%, n = 31) of the participants maintained 100% conviction in their beliefs throughout the 12 months.

Tests of contrasts showed no significant change in the JTC factor score between 3 and 12 months, mean change 0.33, SE 0.24, p = .17, or between baseline and average of the 3 and 12 months values, mean change −0.29, SE 0.20, p = .16, with the chi-square test for the equality of factor scores at the three times being 3.91 with 2 degrees of freedom, p > .05. The fit of the model with time-invariant factor loading was very good, indicated by a CFI of 1, an RMSEA of 0, and a chi-square of 20.90 with 28 degrees of freedom.

Likewise, there was no significant change in belief flexibility factor scores between 3 and 12 months, mean change −0.21, SE 0.37, p = .58, or between baseline and the average of 3 and 12 months, mean change −0.49, SE 0.30, p = .10. The chi-square for constraining for the factor scores to be the same for all three time points was 3.22 with 2 degrees of freedom, p > .05. The fit of the model with time-invariant factor loading was good as indicated by a CFI of 0.98 and an RMSEA of 0.06, but some lack of fit suggested by a chi-square of 40.81 with 24 degrees of freedom.

In summary, there was some evidence of an overall decline in delusional conviction but none in either JTC or belief flexibility.

Hypothesis 3: Baseline JTC and Lack of Belief Flexibility Predict Persistence in Conviction Over Time

As shown in Table 6, the baseline JTC factor score did not significantly correlate with the conviction factor score at any time point, p = .65 [baseline], .41 [3 month], .28 [12 month]. In contrast, the baseline belief flexibility factor score correlated negatively with conviction factor scores at all time points, p<.01 at all time points; that is, individuals with inflexible beliefs at baseline had higher levels of conviction at all time points.

Calculation of Pearson correlations indicated that changes in the factor scores for conviction were not significantly correlated with baseline values of the JTC factor, r = .03 (p = .65) and r = .04 (p = .56), for the changes between 0 and 3 months and between 0 and 12 months, respectively, or the belief flexibility factor for the change between 0 and 12 months, r = −0.04 (p = .52), though the correlation between baseline belief flexibility and change in conviction in the first three months was marginally significant, r = −0.13 (p < .06).

Discussion

Cognitive models of delusions have placed an emphasis on reasoning processes, and this is the largest study so far on this topic. Almost 300 people with delusions were repeatedly assessed on multiple measures of delusion conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility. The sample was of patients who had had at least two acute episodes, and these individuals typically had a lengthy history of psychotic symptoms. If, as cognitive models assert, delusions are maintained by biased reasoning, such biases should be especially apparent. This was confirmed. At the first assessment, 50% of participants showed JTC on the standard beads task, while a similar proportion thought they could not be mistaken in their belief. These proportions are consistent with the smaller studies reported previously.

While previous studies have reported correlations between delusional conviction and reasoning biases, this is the first time that multiple measures have been put together to examine their factor structure. Three distinct factors of conviction, JTC, and belief flexibility emerged, suggesting that the measures used here, along with many of the different measures reported previously, are tapping distinct and coherent constructs. Method variance may have played some part in these results and possibly inflated the effects: Two of the constructs were assessed by binary variables and one by quantitative scoring, and JTC was assessed by a delusion-unrelated cognitive task rather than by delusion-focused interview. Whether other methods would so clearly replicate these three constructs is an empirical question. Another limitation was the amount of missing data. Clearly, a more complete data set would have been preferable, and replication of the results is necessary, but the way in which factor analysis models make allowance for missing data is a strength of this statistical method.

We have also clarified the relationship between these constructs. The inability to think that the delusion could be at all incorrect and to generate alternative explanations for events is distinct from high levels of belief conviction. Belief flexibility is, therefore, not merely a refined method of assessing delusional conviction. Belief flexibility was, nevertheless, associated at all time points with the degree of delusional conviction, and especially highly negatively correlated at baseline, consistent with our earlier report (Garety et al., 2005). Conviction and belief inflexibility, at least when assessed directly with regards to the delusions, are understandably linked and share common variance. How, then, are they different? We can illustrate the point by considering the proportion of the 110 people in our sample with 100% conviction at baseline who affirmed that they may or may not be mistaken on the PM measure. Approximately one quarter (23%) with 100% conviction scored positively on PM, “I am fully convinced but can concede that I may be mistaken”; this differs from “I am fully convinced, and it is impossible that I am mistaken,” which was found in the remaining 77%. People can be equally convinced that they are correct in asserting a given belief but differ in their relationship to that conviction.

Contrary to our previous report, we did not find that JTC was associated with a higher level of delusional conviction (Garety et al., 2005). This may be because JTC is simply only one of many processes contributing to delusional conviction over time. JTC is clearly related to the presence of delusions, but these data suggest that levels of conviction may be more closely related to and possibly influenced by the relatively independent processes of belief flexibility. The main finding in relation to JTC is that, in a large group prone to enduring high conviction beliefs, there were significant levels of JTC. There were also indications of modest relationships between belief flexibility and JTC, as was expected.

All members of the study group had experienced a recent relapse of psychosis, and it is striking that the delusions and reasoning biases were so persistent over the period of follow-up. Although conviction was less stable in that there was a significant decrease in the conviction factor score in the first 3 months, the decrease was small, and substantial levels of symptoms remained. Despite receiving treatment, one third of the group held their delusions with 100% certainty throughout the year of assessment, and only about one third of participants showed a decrease in delusional conviction. Moreover, there were no significant changes in both the reasoning biases. Reasoning biases and conviction were, thus, hardly affected by a year's treatment with medication and, for some in this study, psychological therapy. No previous studies have reported on the stability of belief flexibility, while our findings concerning the stability of JTC are consistent with other reports (e.g., Peters & Garety, 2006). It is noteworthy here that both JTC and belief flexibility are stable, whereas conviction may change—an inflexible way of thinking or limited data gathering do not improve as the delusional conviction reduces; rather, they are enduring. There is, however, some weak evidence, that belief flexibility predicts conviction change in that there was a marginally significant association between baseline belief flexibility and change in conviction at 3 months, consistent with earlier research findings (e.g., Garety et al., 1997). Flexible thinking may render the person more open to experiences or ideas which change their conclusions. However, a limitation of this study is that what could be learned about the relationships between changes in delusional conviction, belief flexibility, and jumping to conclusions was unexpectedly severely curtailed by the relative stability of the variables of interest.

How can this work be taken forward? There are two clear routes. One is to carry out a similar observational study in patients more likely to show change over time, for instance, in individuals with at-risk mental states, patients in early contact with services, or patients entering a prodromal phase. It would be of interest to assess JTC and belief flexibility for delusion-related and neutral materials and to address the limitations of method variance noted above. Assessment of metacognitive beliefs about decision-making and executive functioning abilities to learn about the cognitive factors related to reasoning biases would also be of interest. The second route is more clinically relevant, and that is to alter reasoning biases using precisely targeted interventions and examine the effects on delusional beliefs. That is, to take a manipulationist or interventionist causal model approach (Kendler & Campbell, 2009), thereby potentially providing stronger causal evidence for a role of reasoning biases in delusion maintenance. Reasoning biases are clearly evident in the sample, and even for those not showing the extreme forms, it is likely that if more careful data-gathering and consideration of alternative explanations could be encouraged, then this may help produce a shift from a delusional perspective. The study indicates that increasing data-gathering may be one of several potential techniques that will assist in enabling greater belief flexibility, which is the reasoning process most closely tied to degree of belief in the delusional idea. Potentially appropriate techniques are currently being developed (e.g., Ross et al., 2009; Moritz, Vitzthum, Randjbar, Veckenstedt, & Woodward, 2010; Waller, Freeman, Jolley, Dunn, & Garety, 2011).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (062452). The first author was supported by the Croucher Foundation.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. C. (1984). The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Bentall R. P., Rowse G., Shryane N., Kinderman P., Howard R., Blackwood N., . . . Corcoran R. (2009). The cognitive and affective structure of paranoid delusions: A transdiagnostic investigation of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 236–247. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P. M. (1980). Multivariate analysis with latent variables: Causal modeling. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 419–456. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002223 [Google Scholar]

- Broome M. R., Johns L. C., Valli I., Woolley J. B., Tabraham P., Brett C., & McGuire P. K. (2007). People with an at-risk mental state jump to conclusions. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, s38–s42. doi:10.1192/bjp.191.51.s38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan A., Reed A., Wessely S., Garety P., Taylor P., Grubin D., & Dunn G. (1993). Acting on delusions. II: The phenomenological correlates of acting on delusions. British Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 77–81. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert S. M., & Peters E. R. (2002). Need for closure and jumping-to-conclusions in delusion-prone individuals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190, 27–31. doi:10.1097/00005053-200201000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert S. M., Peters E. R., & Garety P. A. (2010). Delusions and belief flexibility in psychosis. Psychology and psychotherapy: Theory research and practice, 83, 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R. E. J., John C. H., Young A. W., & Over D. E. (1997a). The effect of self-referent material on the reasoning of people with delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 575–584. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R. E. J., John C. H., Young A. W., & Over D. E. (1997b). Normal and abnormal reasoning in people with delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 243–258. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine C., Gardner M., Craigie J., & Gold I. (2007). Hopping, skipping or jumping to conclusions? Clarifying the role of the JTC bias in delusions. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 12, 46–77. doi:10.1080/13546800600750597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D. (2007). Suspicious minds: The psychology of persecutory delusions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 425–457. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Garety P. A., Fowler D., Kuipers E., Bebbington P. E., & Dunn G. (2004). Why do people with delusions fail to choose more realistic explanations for their experiences? An empirical investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 671–680. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Pugh K., & Garety P. (2008). Jumping to conclusions and paranoid ideation in the general population. Schizophrenia Research, 102, 254–260. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P., Fowler D., Kuipers E., Freeman D., Dunn G., Bebbington P., & Jones S. (1997). London-East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis II: Predictors of outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 420–426. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.5.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., Bebbington P., Fowler D., Freeman D., & Kuipers E. (2007). Implications for neurobiological research of cognitive models of psychosis: A theoretical paper. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1377–1391. doi:10.1017/S003329170700013X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., Fowler D. G., Freeman D., Bebbington P., Dunn G., & Kuipers E. (2008). Cognitive-behavioural therapy and family intervention for relapse prevention and symptom reduction in psychosis: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 412–423. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., & Freeman D. (1999). Cognitive approaches to delusions: A critical review of theories and evidence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 113–154. doi:10.1348/014466599162700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., Freeman D., Jolley S., Dunn G., Bebbington P. E., Fowler D. G., & Dudley R. (2005). Reasoning, emotions, and delusional conviction in psychosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 373–384. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., Hemsley D. R., & Wessely S. (1991). Reasoning in deluded schizophrenic and paranoid patients: Biases in performance on a probabilistic inference task. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 194–201. doi:10.1097/00005053-199104000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety P. A., Kuipers E., Fowler D., Freeman D., & Bebbington P. E. (2001). A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 31, 189–195. doi:10.1017/S0033291701003312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock G., McCarron J., Tarrier N., & Faragher E. B. (1999). Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: The psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS). Psychological Medicine, 29, 879–889. doi:10.1017/S0033291799008661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S. R. (1990). Positive–negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: Psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatric Quarterly, 61, 163–178. doi:10.1007/BF01064966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S. R., Opler L. A., & Fiszbein A. (1987). Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Rating Manual. San Rafael, CA: Social and Behavioral Sciences Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., & Campbell J. (2009). Interventionist causal models in psychiatry. Psychological Medicine, 39, 881–887. doi:10.1017/S0033291708004467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln T. M., Ziegler M., Mehl S., & Rief W. (2010). The jumping to conclusions bias in delusions: Specificity and changeability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 40–49. doi:10.1037/a0018118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon M., Mizrahi R., & Kapur S. (2008). 'Jumping to conclusions' and delusions in psychosis: Relationship and response to treatment. Schizophrenia Research, 98, 225–231. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S., Vitzthum F., Randjbar S., Veckenstedt R., & Woodward T. S. (2010). Detecting and defusing cognitive traps: Metacognitive intervention in schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 561–569. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833d16a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S., & Woodward T. S. (2005). Jumping to conclusions in delusional and non-delusional schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 193–207. doi:10.1348/014466505X35678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., & Muthén B. O. (2007). Mplus (Version 5.2) [Computer software]. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Peters E., & Garety P. (2006). Cognitive functioning in delusions: A longitudinal analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 481–514. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross K., Freeman D., Dunn G., & Garety P. (2009). A randomised experimental investigation of reasoning training for people with delusions. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37, 324–333. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So S. H., Garety P. A., Peters E. R., & Kapur S. (2010). Do antipsychotics improve reasoning biases? A review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 681–693. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e7cca6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. (2006). SPSS (Version 15.0). Chicago, IL: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Startup H., Freeman D., & Garety P. A. (2008). Jumping to conclusions and persecutory delusions. European Psychiatry, 23, 457–459. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dael F., Versmissen D., Janssen I., Myin-Germeys I., van Os J., & Krabbendam L. (2006). Data gathering: Biased in psychosis? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32, 341–351. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller W., Freeman D., Jolley S., Dunn G., & Garety P. (2011). Targeting reasoning biases in delusions: A pilot study of the Maudsley Review Training Programme for individuals with persistent, high conviction delusions. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42, 414–421. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warman D. M., & Martin J. M. (2006). Jumping to conclusions and delusion proneness: The impact of emotionally salient stimuli. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 194, 760–765. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000239907.83668.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely S., Buchanan A., Reed A., Cutting J., Everitt B., Garety P., & Taylor P. J. (1993). Acting on delusions: I. Prevalence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 69–76. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward T. S., Munz M., LeClerc C., & Lecomte T. (2009). Change in delusions is associated with change in “jumping to conclusions.” Psychiatry Research. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]