Abstract

Under a shortage of oxygen, bacterial growth can be faced mainly by two ATP-generating mechanisms: (i) by synthesis of specific high-affinity terminal oxidases that allow bacteria to use traces of oxygen or (ii) by utilizing other substrates as final electron acceptors such as nitrate, which can be reduced to dinitrogen gas through denitrification or to ammonium. This bacterial respiratory shift from oxic to microoxic and anoxic conditions requires a regulatory strategy which ensures that cells can sense and respond to changes in oxygen tension and to the availability of other electron acceptors. Bacteria can sense oxygen by direct interaction of this molecule with a membrane protein receptor (e.g., FixL) or by interaction with a cytoplasmic transcriptional factor (e.g., Fnr). A third type of oxygen perception is based on sensing changes in redox state of molecules within the cell. Redox-responsive regulatory systems (e.g., ArcBA, RegBA/PrrBA, RoxSR, RegSR, ActSR, ResDE, and Rex) integrate the response to multiple signals (e.g., ubiquinone, menaquinone, redox active cysteine, electron transport to terminal oxidases, and NAD/NADH) and activate or repress target genes to coordinate the adaptation of bacterial respiration from oxic to anoxic conditions. Here, we provide a compilation of the current knowledge about proteins and regulatory networks involved in the redox control of the respiratory adaptation of different bacterial species to microxic and anoxic environments. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 819–852.

I. Introduction

Respiration is a fundamental process to all living cells in which electrons produced from oxidation of low-redox-potential electron donors such as NADH are transferred sequentially through a series of membrane-bound or membrane-associated protein carriers, the electron transport chain (ETC), which terminates in the reduction of the high-redox-potential electron acceptor, oxygen (Fig. 1a). The free energy released during this electron transfer process is used to drive the translocation of protons across the membrane to generate an electrochemical gradient that can be used for a variety of purposes, such as ATP synthesis and active transport (Fig. 1a). In contrast to the respiratory systems found in the mitochondria of many higher eukaryotic organisms, prokaryotic cells can induce branched-respiratory chains terminating in multiple oxidases with different affinities for the oxygen or use alternative electron acceptors, which contributes to their ability to colonize many microoxic and anoxic environments [reviewed in (61, 183, 186, 197)] (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

Respiratory chain(s) in mammalian mitochondrion and bacteria. (a) A summary of the topology and bioenergetics of a basic aerobic respiratory electron transport system of a mammalian mitochondrion is shown. This figure is adapted from ref. (197). (b) Schematic representation of aerobic and anaerobic nitrate respiration pathways in bacteria. MK, menaquinone; UQ, ubiquinone; Cyt, cytochrome; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; NDH, NADH dehydrogenase; cd1Nir, cd1-type nitrite reductase; CuNir, Cu-type nitrite reductase; Nor, nitric oxide reductase; Nos, nitrous oxide reductase; Nar, membrane-bound nitrate reductase; Nap, periplasmic nitrate reductase; NrfA; cytochrome c nitrite reductase; UQH2, ubihydroquinone; MKH2, menahydroquinone.

The oxidation of organic molecules in cell respiration releases electrons that are transferred to membrane mobile quinones which constitute the link between the electron donating enzymes and the electron accepting enzymes (Fig. 1b). Quinones are small, freely diffusible, lipophilic, membrane-entrapped organic molecules that can carry two electrons and two protons when fully reduced, that is, in the quinol state [for a review, see (221)]. Different kinds of quinones have different electrochemical potentials, and many bacteria can synthesize more than one type of quinone. Escherichia coli synthesize three types of quinones, a benzoquinone (UQ-8), and two naphthoquinones, menaquinone (MK) and demethylmenaquinone. Ubiquinone (UQ) predominates under aerobic conditions, and MK predominates under anaerobic conditions when the cellular state is more reduced (221). From the lipophilic hydroquinones, electrons can be carried to two different types of terminal oxidases: cytochrome c oxidases or quinol oxidases, where dioxygen is reduced to water (Fig. 1b). When oxygen is not present in the medium, electrons can be transmitted to alternative reductases that reduce substrates such as nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O), dimethyl-sulphoxide (DMSO), trimethylamine N-oxide, sulfate, sulfite, and fumarate as final electron acceptors. Among them, nitrate is one of the essential environmental components in the biosphere. It serves as a nutrient for plants and microorganisms, and is used as an electron acceptor by many bacteria, archaea, and also by several eukaryotes (109, 125, 266). During anaerobic respiration, nitrate can be reduced to dinitrogen gas (N2) or to ammonium. The anaerobic reduction of nitrate to N2 gas is called denitrification, and it constitutes one of the more important processes in the N-cycle (141). This reductive process occurs in four stages, reduction of NO3− to NO2− and via the gaseous intermediates NO and N2O to N2. The enzymes involved in denitrification are nitrate-, nitrite-, nitric oxide-, and nitrous oxide reductase, encoded by nar/nap, nir, nor, and nos genes, respectively [reviewed in (125, 247, 248)]. In agriculture and wastewater treatment, denitrification by microorganisms is an important issue due to the economical, environmental, and public health implications of this process (10, 105).

The bacterial respiratory flexibility requires a regulatory strategy which ensures that prokaryotic cells sustain life under different environments in response to changing oxygen tension. To date, three main modes to sense O2 have been described in bacteria: two types by direct interaction of O2 with a membrane protein receptor (as in the heme-based sensor kinase FixL in rhizobia [reviewed in (83, 101, 205)] or by interaction with a regulatory protein such as the Fe-S-based fumarate and nitrate reductase regulatory protein (Fnr) in E. coli [reviewed in (65, 68, 84, 53, 101, 261)]. In addition, a third type of O2 perception is based on monitoring environmental oxygen concentration by sensing changes in the redox state of molecules or pools of molecules within the cell. These changes are detected by various protein sensors that convert the redox signals into regulatory output at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. Redox signals are many and diverse, and can involve redox-active cofactors such as heme, flavins, pyridine nucleotides, iron-sulfur clusters, and redox-sensitive amino-acids chains such as cysteine thiols among others [reviewed in (3, 14, 102)]. This article focuses on a comparative study about the regulatory mechanisms used by different bacterial groups to undergo respiratory shifts from oxic to microoxic and anoxic environments.

II. Aerobic Respiration Under Microoxic Conditions

The branched ETC present in many bacteria often contains several terminal oxidases (Fig. 1b), which can be grouped into two main types based on the substrates used as electron donors [reviewed in (61, 177, 183)]. Reduced c-type cytochromes donate electrons to cytochrome oxidases, whereas hydroquinones deliver electrons to quinol oxidases (Fig. 1b). Both types of oxidases belong to the extensively studied family of heme-copper oxidases (HCOs). The common denominator in HCOs is a membrane-integral subunit I that carries as cofactors a low-spin heme and a high-spin heme-copper binuclear center (CuB site) where reduction of O2 to H2O takes place (Fig. 2). Among this family, quinol oxidases possess a cofactor-free subunit II, whereas cytochrome c oxidases have cofactors bound to subunit II. In most cases, this is a binuclear Cu–Cu center (CuA site) that is liganded by six highly conserved amino acids (87, 176). The HCO superfamily is very versatile due to the wide range of electron donors they can use, their subunit composition, and the types of heme groups that they contain. Studies of evolutionary relationships led to classifying the HCO enzymes in three different types (176, 177) (Fig. 2): (i) type A oxidases (oxidases aa3), which are structurally and functionally close to mitochondrial oxidases, (ii) type B oxidases, grouped as cytochrome oxidases bo3, and (iii) type C oxidases, which include the cytochrome c oxidases cbb3. To gain new insights into the oxygen respiration process, C-family HCOs from pathogenic bacteria have been recently structurally characterized, and it has been shown that C-HCOs differs from the two other HCO families, A and B (40). The X-ray structure of the C-family cbb3 oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri shows an electron supply system different from families A and B.

FIG. 2.

Summary of the main types of heme–copper oxygen reductases belonging to the A, B, and C families and the bd-type quinol oxidase.

Under O2 limitation (microoxic conditions), many bacteria induce high-affinity oxidases to respire traces of molecular oxygen. The cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase is known to have a high affinity for oxygen. Thus far, the enzyme from Bradyrhizobium japonicum is the only cytochrome cbb3 oxidase in which substrate affinity has been measured showing a Km for dioxygen in the order of 7 nM (185). As a consequence, it allows respiration under microoxic conditions, such as those encountered by rhizobia in the legume nodule ([O2] estimated to be 30 nM) (61). This oxidase has a subunit II (CcoO or FixO) that is a monoheme c-type cytochrome instead of the CuA-containing protein (67, 176). Subunit III in cbb3-type oxidases, which is a diheme cytochrome c (CcoP or FixP), is thought to relay the electrons from the cytochrome bc1 complex via CcoO to the redox centers of subunit I (126, 265). Subunit III of all other HCOs is cofactor-free, just like the nonconserved small subunit IV (176). Homology modelling and recent studies on the thermodynamic properties of the redox centers in cbb3 oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides using a combination of optical and electron paramagnetic resonance redox titrations have allowed the characterization of the cbb3 active site (191). Furthermore, it has been recently shown that the redox-coupled proton movement in the proximal cavity of cbb3-enzymes contributes to the low redox potential of heme b3, and suggests its potential implications for the high oxygen affinity of these enzymes (219).

In addition to C-family cbb3 oxidases, another family of high-affinity oxidases comprises cytochrome bd-type oxidases (29). Among them, the bd oxidase of E. coli is known to have a high affinity for oxygen showing the Kd(O2) value of 0.28 μM (19). The bd-type oxidases are quinol oxidases that show no sequence homology to any subunit of heme-cooper family members. They do not contain any copper atoms in the catalytic center, but probably replace the CuB atom with a second heme (Fig. 2). In contrast to the heme-copper enzymes that are found at most branches of the tree of life, bd-type oxidases are only found in bacteria and archaea (183). The bd-type cytochromes do not pump protons and, therefore, have a lower total energetic efficiency compared with the heme-copper type oxidases (29).

A. Oxygen control of cbb3 oxidase expression

As just mentioned, cbb3 oxidase is quite distinct from other bacterial HCOs in terms of its strategy for receiving electrons, the heme prosthetic group present in the active site, and its affinity for oxygen. Cytochrome cbb3 oxidases have been purified from several organisms, including Paracoccus denitrificans, Rho. sphaeroides, Rhodobacter capsulatus, and Br. japonicum [reviewed in (179)]. The biogenesis of this multisubunit enzyme, encoded by the ccoNOQP operon, depends on the ccoGHIS gene products, which are proposed to be specifically required for cofactor insertion and maturation of cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidases (185). In the facultative photosynthetic model organism Rho. capsulatus, CcoN, CcoO, and CcoQ assemble first into an inactive 210 kDa sub-complex, which is stabilized via its interaction with CcoH and CcoS. Binding of CcoP, and probably subsequent dissociation of CcoH and CcoS, generates the active 230 kDa complex (126). Recent results have proposed that CcoH behaves more similar to a subunit of the cbb3 oxidase rather than a transient assembly factor per se (173). The insertion of the heme cofactors into the c-type cytochromes CcoP and CcoO precedes sub-complex formation, while the cofactor insertion into CcoN could occur either before or after the 210 kDa sub-complex formation during the assembly of the cbb3-type oxidase (126). CcoQ is required for optimal cbb3-type oxidase activity, because it stabilizes the interaction of CcoP with the CcoNO core complex, leading subsequently to the formation of the active 230-kDa cbb3-type oxidase complex (178).

Genes encoding the cbb3 complex were initially isolated from rhizobia and named fixNOQP due to its requirement for symbiotic nitrogen fixation (185). Since then, orthologous genes called ccoNOQP were identified in other Proteobacteria including photosynthetic and pathogenic bacteria, suggesting that this oxidase is not only required for diazotrophs to sustain N2 fixation, but also for the successful colonization of anoxic tissues by human pathogens [reviewed in (50, 61, 179)]. Regulation of ccoNOQP expression has been investigated in many bacteria with oxygen being the key effector that controls its expression. To date, four different strategies that activate the ccoNOQP operon have been described (Fig. 3): (a) in Rho. sphaeroides, Pa. denitrificans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae (UPM791), and Rho. capsulatus, Fnr acts as oxygen sensor and transcriptional factor; (b) in rhizobial species, such as Sinorhizobium meliloti, Br. japonicum, and Azorhizobium caulinodans, FixLJ/FixK is the system implicated in the activation of ccoNOQP under oxygen deprivation; (c) in Rhi. leguminosarum (VF39) and Rhizobium etli CFN42, a mixed regulation strategy operates that involves both Fnr and FixK proteins; (d) and finally, in the human pathogenic bacteria Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni (ɛ-Proteobacteria), which lack fnr and fixLJ-fixK genes, it has been proposed that cbb3 may be constitutively expressed allowing the growth under microoxic conditions in its hosts. In addition to the positive control of Fnr on fixNOQP expression, it has been shown in Rhi. etli that two novel Fnr-type transcriptional regulators (StoRd and StoRf, symbiotic terminal oxidase regulators) have a negative control on microoxic expression of fixNOQP genes (100).

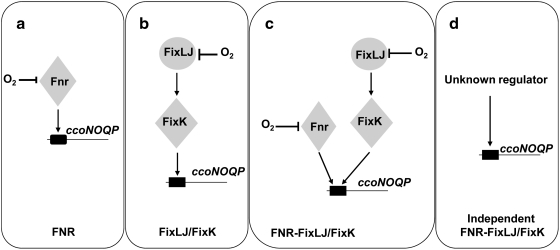

FIG. 3.

Regulation strategies of ccoNOQP gene transcription. Four regulation strategies have been described in several bacterial groups (see text for details) that involve (a) Fnr, (b) FixLJ-FixK, (c) Fnr and FixLJ-FixK, or (d) an unknown regulator. Gene transcriptional activation is indicated by arrows. Protein inactivation by O2 is indicated by perpendicular lines. This figure is adapted from ref. (50).

1. Involvement of Fnr

The O2-sensitive protein Fnr belongs to the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (Crp) superfamily of transcription factors that trigger physiological changes in response to a variety of metabolic and environmental cues [reviewed in (53, 65, 68, 84, 101, 103, 124, 261)]. All members of this family are predicted to be structurally related to Crp. They consist of four functionally distinct domains: (i) a sensor domain, (ii) a series of β-strands (β-roll structure) that form a loop-like structure making contact with the RNA polymerase holoenzyme (RNAP), (iii) a long α-helix acting as a dimerization interface, and (iv) a C-terminal helix-turn-helix motif (H-T-H) involved in DNA binding (Fig. 4a). The best-characterized Fnr protein is that of E. coli. In E. coli, Fnr acts as a direct oxygen sensor and is the primary transcriptional regulator of the switch between aerobic and anaerobic growth. Thus, under anoxic conditions, Fnr is in its active state and is able to bind specific palindromic sequences of DNA (Fnr box). Once bound to DNA, Fnr activates target gene expression by recruiting RNAP or represses transcription by preventing the formation of productive RNAP:DNA complexes (53). Active Fnr regulates genes involved in the adaptation of E. coli for anaerobic growth and controls one of the best-studied gene regulatory networks in the cell. Very recently, the Fnr regulatory network has been reviewed by Tolla and Savageau (238). Generally, Fnr activates genes encoding products involved in anaerobic metabolism, such as the nar operon (nitrate reductase), the dms operon (DMSO reductase), and the frd operon (fumarate reductase), and represses genes encoding products involved in aerobic metabolism, such as the sdh operon (succinate dehydrogenase) and ndh (NADH dehydrogenase II). Fnr is activated under anoxic conditions by the acquisition of one [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster per monomer (designated 4Fe-Fnr). Each [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster is ligated by four cysteine residues (Cys20, Cys23, Cys29, and Cys122), and the presence of the cluster promotes Fnr dimerization, increasing its capacity to bind specifically to DNA (52, 54, 132) (Fig. 4a). The [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster is susceptible to be attacked by O2, resulting in rapid and reversible conversion to a [2Fe-2S]2+ and finally to apoFnr on exposure to high oxygen concentrations. In addition to its reaction with oxygen, the Fnr [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster is also sensitive to NO. On exposure to NO, [4Fe-4S]2+ becomes nitrosylated, forming a combination of monomeric and dimeric dinitrosyl-iron-cysteine complexes, again abolishing its ability to bind DNA (53, 57). It has been reported that Fnr represses genes involved in NO detoxification (e.g., hmp, which encodes the flavohemoglobin) (182). When cultures of E. coli are exposed to NO, Fnr repression of hmp is relieved, suggesting that the reaction between Fnr and NO is physiologically significant. This suggestion is supported by transcript profiling experiments which reveal that the abundances of many Fnr-activated genes are lower, and many Fnr-repressed genes are higher, when E. coli is exposed to NO (119, 187).

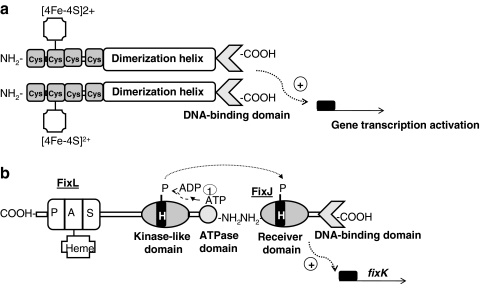

FIG. 4.

Functional domains and model of Fnr and FixLJ mediated oxygen activation. (a) Fnr senses oxygen via an iron-sulfur center, which is coordinated with four cysteine residues. Under anoxic conditions, Fnr is in its active state and it promotes DNA-binding by formation of a homodimer leading to activation of gene transcription. (b) FixL is an oxygen receptor in which oxygen binds directly to a heme group that is coordinated to a histidine residue within a PAS domain. Detection of low oxygen tension changes the conformation of the input PAS domain, rendering increased autophosphorylation activity of the transmitter domain in His residue and repressing the phosphatase activity of FixL. FixL activates FixJ transcriptional activity by transferring the phosphoryl group to the N-terminal domain of FixJ (+) gene transcription activation.

2. Involvement of FixLJ/K

In some rhizobial species, the fixNOQP operon is under the control of one Fnr-type transcriptional regulator named FixK, which is also able to recognize Fnr boxes but lacks [4Fe–4S]2+ clusters. FixK is thereby unable to sense oxygen directly. In this case, it is the two-component regulatory system FixLJ that ensures oxygen sensing under low-oxygen conditions and activates the transcription of the fixK gene. This regulatory system FixLJ/FixK has been studied in rhizobial species where it controls the expression of genes for microoxic respiration, as well as various other functions, in response to low oxygen (28, 56, 83, 145, 160). Interestingly, it has been shown that Rhodopseudomonas palustris FixK is not only required for optimal microaerobic growth, but is also required for phototrophic and autotrophic growth, and for growth on aromatic compounds (194). These authors also propose that FixK helps the control of the transition of R. palustris to anaerobic growth by activating the expression of the oxygen-sensing Fnr homolog, AadR.

The biochemistry of the FixLJ two-component system has been characterized in Si. meliloti and Br. japonicum (96, 211, 223). FixL is a histidine kinase that binds heme at an amino-terminal PAS domain (Fig. 4b). PAS domains are present in many proteins involved in the sensing of oxygen, redox, or light. They were first found in eukaryotes, and were named after homology to the Drosophila period protein (PER), the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein (ARNT), and the Drosophila single-minded protein (SIM). The binding of oxygen to heme inactivates FixL kinase activity. FixL, and the response regulator and transcription factor FixJ form a complex in which FixJ allosterically stimulates autophosphorylation of FixL. At very low oxygen concentrations, FixL transphosphorylates FixJ, which, in turn, activates expression of the transcription factor gene fixK (Fig. 4b). In Br. japonicum, the nitrogen-fixing root-nodule endosymbiont of soybean (Glycine max), a FixK-like protein called FixK2, acts as the key distributor of the low-oxygen signal perceived at the level of the FixLJ two-component regulatory system. FixK2 is one of the 16 (Crp/Fnr)-type transcriptional regulators whose genes are present in the Br. japonicum genome [reviewed in (146)]. FixK2 recognizes a palindromic sequence motif (TTG-N8-CAA, termed the FixK2 box) that is located around position–41 upstream of the transcription start site in the regulated promoters. Microoxically induced targets of FixK2 include the operons fixNOQP and fixGHIS, both essential for microoxic respiration, several heme biosynthesis genes (hemA, hemB, hemN1, and hemN2), denitrification genes, and some hydrogen oxidation genes (hup genes) (16, 160). Recently, the Br. japonicum FixK2 regulon was unraveled by using a transcriptomics approach (145). DNA binding site predictions, together with a FixK2-dependent in vitro transcription assay, demonstrated that the fixNOQP operon is a direct target for FixK2. The latter studies, carried out with purified FixK2 protein, showed that FixK2 is sufficient to activate transcription in vitro without any identified effector (148). This is puzzling in view of the fact that all Crp/Fnr-like proteins can be positively or negatively modulated in their activity through bound cofactors or intrinsic, reactive amino acids (101). However, recent findings have reported that posttranslational control occurs at FixK2, whereby a critical cysteine at position 183 in the polypeptide chain is a target for oxidation. This provides a second, important means of affecting FixK2 activity, in addition to the regulation of its expression by FixLJ (147).

III. Redox Control of the Adaptation of Aerobic Respiration from Oxic to Microoxic Conditions

A. E. coli ArcBA

E. coli has three terminal quinol oxidases, of which one is a heme-copper bo3 oxidase and two are bd-type oxidases [reviewed in (183, 186)]. The quinol bo3 oxidase contains a heme-Cu cofactor (CuB) and is essential when oxygen is present at high concentrations. The protein complex is encoded by the cyoABCDE operon (186). Under conditions of low aeration, the high-affinity bd oxidase is the preferred terminal reductase in E. coli (29). The structural components are encoded by the genes cydAB, which form a heterodimer. CydC and D are encoded in the same operon as CydA and B and thought to form a heme transporter necessary for cytochrome bd oxidase biogenesis (29). There is a third terminal oxidase present in E. coli encoded by the genes cyxAB. It is a bd type oxidase but its function is unclear. It appears to be expressed under microoxic conditions (29).

Cytochrome bd oxidase prevails under oxygen-limiting conditions. Consistent with these properties, transcription of the cydAB operon is activated when oxygen becomes limiting. Under fully anoxic conditions, cydAB expression is subsequently repressed to an intermediate level relative to microoxic and oxygen-rich conditions (241). It is now solidly established that this oxygen control is achieved through the combined action of the oxygen sensing transcription factor Fnr and the aerobic respiration control (Arc)B/ArcA two-component system (217). Under anoxic conditions, Fnr acts as a repressor of the cydAB operon (Fig. 5). ArcBA is a two-component regulatory system involved in the transcriptional regulatory network that allows facultative aerobic bacteria to sense and respond to various respiratory conditions. While the Fnr protein is directly implicated in sensing oxygen, the ArcBA system activity is proposed to be modulated by the redox state of the quinones in the membrane (137, 138). The ArcBA system comprises the ArcB protein, a tripartite membrane-bound sensor kinase, and the cognate response regulator ArcA (Fig. 6a). ArcB belongs to the subclass of hybrid sensor kinases that also includes BarA, BvgS, EvgS, LemA (GacS), RteA, and TorS (2, 138). Under limiting oxygen conditions, ArcB autophosphorylates residue His292 and, through a phosphorelay system involving Asp576 and His717, transphosphorylates ArcA (Fig. 6a). It has been previously reported that histidine kinases act as homodimers and that they autophosphorylate by an intermolecular reaction (229). That is, the gamma-phosphoryl group of ATP, which is bound to one monomer in the homodimer, is transferred to the other monomer. On the contrary, it has been recently proposed that ArcB autophosphorylates through an intramolecular and not through an intermolecular reaction as previously proposed (175).

FIG. 5.

Regulation of bd and bo3 terminal oxidase expression in Escherichia coli. Fnr and ArcB provide negative or positive transcriptional control in response to oxygen availability. The genes cydAB and cyoABCDE encode bd and bo3 oxidase polypeptides, respectively. Positive regulation (+) is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation (−) is indicated by perpendicular lines.

FIG. 6.

Functional domains and model of ArcBA-mediated redox control. (a) ArcB is attached to the membrane by two transmembrane regions (TM). A linker region containing a putative leucine-zipper and a PAS domain connects TM2 with the catalytic domains. The two cysteine-residues (Cys180 and Cys241) in the linker region are able to undergo oxidation and to form intermolecular disulfide bonds between both ArcB monomers. The transmitter domain (H1) contains the conserved His292 together with the G1 and G2 nucleotide-binding motifs. The receiver domain (D1) harbors the conserved Asp576, and the histidine phosphotransfer domain (Hpt/H2) contains the conserved His717. The ArcA component is represented with its N-terminal receiver domain carrying the conserved Asp54 and its C-terminal H-T-H) domain. This figure is adapted from ref. (138). (b) MKH2, which predominates under anaerobic conditions, would be oxidized in the presence of low levels of oxygen (∼20% aerobiosis), leading to increased levels of MKs and inactivation of ArcB kinase activity. UQH2 predominate under microoxic conditions (∼80% aerobiosis), giving rise to activation of ArcB kinase activity. In fully aerobic conditions (100%), the UQH2 pool is subjected to oxidation, which results in increasing levels of UQs and oxidation of the key cysteines, leading to inactivation of the ArcB kinase activity. This figure is adapted from ref. (18).

On a shift to aerobic conditions, ArcB can form intermolecular disulphide bonds via Cys180 and Cys241 located in the PAS domain (Fig. 6a). The kinase activity of ArcB is highly dependent on this covalent linkage (137). The regulatory mechanisms that underlie the function of the ArcBA two-component system have been the subject of numerous studies. ArcB does not sense oxygen directly but is thought to sense the redox state of the UQ-ubiquinol pool in the aerobic respiratory chain, because UQ inhibits ArcB autokinase activity (137). However, this regulatory network becomes complex, as recent observations could not demonstrate a correlation between ArcB activation and oxygen availability (18). Bekker and colleagues (18) proposed that the in vivo activity of ArcB in E. coli is also modulated by the redox state of the MK pool and that the UQ/ubiquinol ratio is not the only determinant of ArcB activity (Fig. 6b). This combined regulation by the redox state of the UQ pool and MK pool provides a mechanism to explain the observed complex regulation of ArcB activation at variable rates of oxygen supply (Fig. 6b). Menaquinols would be the dominant activators under anoxic conditions, where the size of the UQ pool is approximately five times less than the size of the MK pool (18). Recent work has used controlled chemostat cultures subject to gradually decrease oxygen concentration to study the effects of oxygen availability on the transcriptome, redox state of the UQ-ubiquinol, outer membrane protein profiles, and terminal oxidase proteins of E. coli K-12 (208). A probabilistic model was used to predict the activity of ArcBA across the aerobiosis range. The model implied that the activity of the regulator ArcA correlated with aerobiosis, but not with the redox state of the UQ pool. Rolfe and colleagues (208) have proposed that, at least under the conditions used in this work, the rate of fermentation product synthesis (qacetate) exerts a greater influence on ArcA activity than the redox state of the quinone pools. It is perhaps not surprising that, as a regulator of genes that have fundamental roles in different processes of the bacterial metabolism (aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration, and fermentation), ArcB should integrate the response to multiple signals (e.g., UQ, MK, acetate, and other fermentation products) in response to different growth conditions.

Phosphorylated ArcA activates genes or operons needed to use traces of oxygen in the medium, for example, those for terminal oxidase bd, and represses expression of the aerobic cytochrome bo3 terminal oxidase (136). Regulation of bd and cytochrome bo3 terminal oxidases in response to oxygen concentration variation is also controlled by Fnr as just described (Fig. 5b). Fnr inhibits cyd and cyo gene activation from 0% to 10% oxygen tension. However, ArcA represses cyo expression and activates cyd transcription when O2 concentration is between 10% and 20% (241) (Fig. 5). These authors proposed that when the oxygen tension drops, ArcA is phosphorylated by ArcB and activates cydAB transcription reaching a maximum at <2% O2 tension. When oxygen is decreased further, Fnr becomes active and represses cydAB transcription. Fnr repression of cydAB requires the presence of a functional ArcA protein (51, 99). According to this observation, Fnr has been proposed to serve as an antiactivator by counteracting ArcA-mediated activation, rather than directly repressing transcription. This indirect regulation of cydAB repression by Fnr through ArcA is supported by gene expression profiling analyses where nearly two-thirds of the genes for which expression is affected by Fnr are also affected by ArcA (209, 210). In addition to controlling genes encoding respiratory oxidases, ArcA∼P represses the expression of genes encoding dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and enzymes of the glyoxylate shunt. Recent studies have demonstrated that ArcAB exerts an important influence on carbon and redox balances in E. coli growing under carbon-limited conditions with a restricted oxygen supply (163).

B. Rhodobacter species RegBA/PrrBA

Photosynthetic bacteria such as Rho. Capsulatus and Rho. sphaeroides conserve energy under oxic or microoxic conditions by driving electrons through branched electron transfer chains to terminal oxidases with different affinity for oxygen (Fig. 7). One ubiquinol oxidase is found in Rho. capsulatus (cydAB), while two are found in Rho. sphaeroides (qoxBA and qxtAB). The cytochrome c oxidases depend on the cytochrome bc1 complex (petABC in Rho. capsulatus and fbcFBC in Rho. sphaeroides), and cytochromes c2 (cycA) or cy (cycY). While Rho. capsulatus contains only one cbb3-type oxidase (ccoNOQP), an aa3- (ctaDC) and a cbb3-type oxidase (ccoNOQP) are found in Rho. sphaeroides [reviewed in (72, 120, 166, 233, 258)]. Gene expression experiments using the lacZ as reporter gene revealed that the cbb3 oxidase from Rho. capsulatus and aa3 oxidase from Rho. sphaeroides are considered low-oxygen-affinity oxidases which are induced under oxic conditions (233). However, the Rho. capsulatus ubiquinol bd oxidase and Rho. sphaeroides cbb3 oxidase are classified as high-affinity terminal oxidases and are highly induced under oxygen-limiting conditions (233).

FIG. 7.

Aerobic respiratory chains in Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. The quinone-reducing (left) and quinol-oxidizing (right) branches with terminal oxidases induced under oxic conditions (gray boxes), and microoxic conditions (white boxes), are shown. Black arrows indicate the influx of reducing equivalents.

RegBA/PrrBA are members of the family of the two-component regulatory systems present in a large number of Proteobacteria. These proteins are named RegBA in Rho. capsulatus, Rhodovulum sulfidophilum, and Roseobacter denitrificans [reviewed in (72, 258)], PrrBA in Rho. sphaeroides (106, 167), ActSR in Si. meliloti (73) and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (8), RegSR in Br. japonicum (15), and RoxSR in Ps. aeruginosa (46). In Rhodobacter species, the RegBA/PrrBA regulon encodes proteins involved in numerous energy-generating and energy-utilizing processes such as photosynthesis, carbon fixation, nitrogen fixation, hydrogen utilization, aerobic and anaerobic respiration, and aerotaxis [reviewed in (72, 233, 258)]. Recent analyses of the transcriptome and the proteome of Rho. sphaeroides prrA mutant revealed that, in addition to the numerous PrrA gene targets already known, genes encoding proteins whose functions are involved in intermediary metabolism, repair of DNA and protein damage, cell motility and secretion, and translation constituted new targets for PrrA regulation (77).

The RegBA/PrrBA two-component systems comprise the membrane-associated RegB/PrrB histidine protein kinase, sensing changes in redox state and its cognate PrrA/RegA response regulador. Under conditions where the redox state of the cell is altered due to generation of an excess of reducing potential, produced by either an increase in the input of reductants into the system (e.g., presence of reduced carbon source) or a shortage of the terminal respiratory electron acceptor (e.g., oxygen deprivation), the kinase activity of RegB/PrrB is stimulated relative to its phosphatase activity (72). This increases phosphorylation of the partner response regulators RegA/PrrA, which are transcription factors that bind DNA and activate or repress gene expression. The membrane-bound sensor kinase proteins RegB/PrrB contain an H-box site of autophosphorylation (His225), a highly conserved quinone binding site (the heptapeptide consensus sequence GGXXNPF, which is totally conserved among all known RegB homologues), and a conserved redox-active cysteine (Cys265, located in a “redox box”). The mechanism by which RegB controls kinase activity in response to redox changes has been an active area of investigation. A previous study demonstrated that RegB Cys265 is partially responsible for redox control of kinase activity. Under oxidizing growth conditions, Cys265 can form an intermolecular disulfide bond to convert active RegB dimers into inactive tetramers (235) (Fig. 8a). The highly conserved sequence, GGXXNPF, located in a short periplasmic loop of the RegB transmembrane domain has also been implicated in redox sensing by interacting with the UQ pool [Swem et al. (234)] (Fig. 8a). Recently, kinase activity assays together with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements indicated that RegB with a substitution in the cytosolic cysteine by serine in position 265 (RegB C265S) binds both oxidized and reduced UQ with almost equal affinity. However, only the oxidized UQ inhibits RegB kinase activity (259). The observation that the RegB C265S mutant is still redox responsive suggests that UQ binding is a signal input able of functioning independently from Cys265. However, the contribution of each redox sensing inputs is unknown.

FIG. 8.

Proposed models for redox-mediated sensing by RegBA/PrrBA. (a) In Rho. capsulatus, the conserved cysteine C265 of RegB functions as a redox switch that controls RegB kinase activity through a metal-dependent formation of a disulfide bond in response to redox changes (235). Binding of UQ to the RegB transmembrane domain has also been proposed to inhibit RegB kinase activity, whereas UQH2 does not affect RegB kinase activity (234). (b) In Rho. sphaeroides, the cbb3 oxidase generates an “inhibitory” signal that can directly stimulates the phosphatase activity of PrrB. Under low oxygen conditions when the electron flow is reduced, the inhibitory signal from cbb3 is weakened, and PrrB would retain its kinase activity (165). PrrC has been proposed as a signal mediator between the cbb3 oxidase and the sensor kinases PrrB (7).

In Rho. sphaeroides, the PrrB histidine kinase is a bifunctional enzyme that possesses both kinase and phosphatase activities (168). Several reports proposed that the cbb3 oxidase transduced an inhibitory signal to the PrrBA under oxic conditions to prevent gene expression (165, 166). The dual function of the cbb3 oxidase as both terminal oxidase and O2/redox sensor and modulator of PrrB kinase/phosphatase activity represents a new model of redox sensing. In this model (Fig. 8b), the UQ binding site within the PrrB transmembrane domain is not required for monitoring the PrrB kinase activity. Instead, a control based in direct interaction between components of the terminal oxidase cbb3 and PrrB is strengthened (122).

The photosynthetic regulatory response protein (PrrC) is a Sco homolog present in Rho. sphaeroides (75). Sco is thought to be involved in donating copper to the CuA center and, thus, it has a central role in cytochrome oxidase synthesis (12). Rho. sphaeroides PrrC, which reduces Cu2+ to Cu+, and possesses disulfide reductase activity, is required for the correct functioning of the sensor kinase/phosphatase PrrB (7). Similarly, the Rho. capsulatus SenC protein, homologous to PrrC, which is required for synthesis of a functional cytochrome c oxidase (232), might act as a signal mediator between the Q-pool and the sensor kinase RegB. However, at present, there is no direct evidence that SenC or cbb3 oxidase directly modulates the activity of the RegBA regulatory system.

RegA/PrrA contain conserved domains that are typical in two component response regulators such as a phosphate accepting aspartate, an “acid box” containing two highly conserved aspartate residues and a H-T-H DNA-binding motif (72). The phosphorylated form of RegA/PrrA has increased DNA binding capacity (129, 189). Under oxidizing conditions, RegB/PrrB shifts the relative equilibrium from the kinase to the phosphatase mode resulting in a dephosphorylated inactive RegA/PrrA form. Despite this evidence, it has been reported that inactivation of the regA gene affects expression of many different genes under oxidizing (aerobic) conditions, suggesting that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated RegA/PrrA may be active transcriptional regulators (72, 233). In this context, it has been shown that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of RegA/PrrA are capable of binding DNA in vitro and activating transcription (189). Based on recent findings, there are two types of PrrA binding sites within the promoter of Rho. sphaeroides hemA, which codes for one of two isoenzymes catalyzing 5-aminolevulinate synthesis: (i) one site for which unphosphorylated PrrA has greater affinity, and (ii) another for which phosphorylated PrrA has greater affinity (190). Several consensus DNA binding sequences have been previously reported for PrrA (128, 139) and its homologs RegA in Rho. capsulatus (233, 253) and RegR in Br. japonicum (73, 134). While there is a measure of agreement in terms of the assignment of two imperfect quasisymmetrical inverted repeats, or half-sites separated by a spacer region possessing variable length, the DNA sequence per se shows a high degree of degeneracy. Very recently, it has been demonstrated that PrrA can bind in vitro to DNA sequences with different lengths in the spacer regions between the half sites (76).

In Rho. capsulatus, RegA has been reported to activate the expression of both the bd and cytochrome cbb3 oxidases (Fig. 9a). An interesting paradox is that RegA activates expression of cytochrome cbb3 oxidase under oxic conditions, but represses expression of this oxidase under anoxic conditions (233). In many respects, this is similar to what occurs in E. coli where ArcA acts as an oxic activator, as well as an anoxic repressor of cytochrome bo3 oxidase (see section III.A; Fig. 5b).

FIG. 9.

Regulation of bd and cbb3 terminal oxidases expression in Rho. capsulatus (a) and Rho. sphaeroides (b). In Rho. capsulatus, RegA regulates gene transcription in response to both oxic and anoxic conditions, FnrL, HvrA, in response to anaerobiosis, and AerR and CrtJ in response to aerobiosis. In Rho. sphaeroides, FnrL, PrrA, and PspR regulate gene transcription in response to anoxic conditions. Genes cydAB and ccoNOQP encode bd and cytochrome cbb3 oxidase polypeptides, respectively. Positive regulation (+) is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation (−) is indicated by perpendicular lines.

Terminal oxidase expression in Rho. capsulatus involves a complex set of regulators beyond that of RegBA. In response to oxygen availability, these regulators provide negative or positive transcriptional control to coordinate enzyme synthesis for optimal growth. A regulatory scheme for control of terminal oxidases in response to oxygen availability is shown in Figure 9a. Specifically, in Rho. capsulatus cytochrome cbb3, oxidase expression is regulated by RegA and FnrL, as well as moderately regulated by HvrA, an activator of various photosynthetic components under low-light conditions [(Swem et al. (231)]. Ubiquinol bd oxidase expression was found to be regulated by RegA and HvrA as well as by AerR and CrtJ, which are aerobic repressors of photosystem gene expression (231). In Rho. sphaeroides, microarray analyses and quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction showed that both PrrA and the repressor of genes involved in photosynthesis, PspR, affect the transcription of the ccoNOQP operon (Fig. 9b). The absence of PrrA prevented the expression of the cco genes, and a prrA-pspR double mutant leads to derepresion of ccoNOQP operon (34). The fact that PpsR binds directly the cco promoter indicates that PrrA/PspR could act as an antirepressor/repressor system in which PspR acts as the direct repressor of the cco operon and PrrA is the PspR antirepressor regulator (34). Thus, RegBA/PrrBA appears to be just one component of a more complex regulatory network that controls many cellular processes. In this context, recent comparative genomics analyses and characterization of Rho. sphaeroides FnrL regulon have revealed that ccoNOQP is also positively controlled by this protein (68).

C. Pseudomonas species RoxSR

Pseudomonads are opportunistic pathogens that inhabit a wide variety of environments, including soil, water, and animal, human,- and plant roots. They are endowed with versatile respiratory chains that can be adapted to changing oxygen concentrations. Although they preferentially obtain energy from aerobic respiration, some of them, such as Ps. aeruginosa, can also grow anaerobically using nitrate as a final electron acceptor, or can even ferment arginine and pyruvate (254). The genome sequence and some biochemical studies have revealed that Pseudomonads have at least five terminal oxidases for aerobic respiration [reviewed in (183)] (Fig. 10a). In Ps. aeruginosa, UQs can be oxidized by either a bo3-type oxidase, a cyanide-insensitive oxidase (named CIO), or a bc1 complex that transfers electrons to a cytochrome c, which, in turn, can be oxidized by an aa3 oxidase or by two related cbb3 oxidases, named cbb3-1 and cbb3-2 (46, 47, 49). The Pseudomonas putida genome contains genes coding for all these terminal oxidases (161). Each oxidase is expected to have a specific affinity for oxygen, efficiency of proton translocation, and redox potential. Ps. aeruginosa has three predicted high-affinity oxidases; CIO, cbb3-1, and cbb3-2, which are believed to be important in the adaptation to oxygen-limiting conditions during growth under microoxic conditions. In this context, Alvarez-Ortega and Harwood (1) reported that any one of CIO, cbb3-1 and cbb3-2, could support growth under 2% oxygen concentrations and that either of cbb3-1 and cbb3-2 was indispensable for the growth under 0.4% oxygen.

FIG. 10.

Aerobic respiratory chains (a) and regulation of CIO, cbb3, and aa3 terminal oxidase expression (b) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In (a), the quinone-reducing (left) and quinol-oxidizing (right) branches with terminal oxidases induced under oxic conditions (gray boxes), and microoxic conditions (white boxes), are shown. In (b), Anr and RoxSR regulators provide negative or positive transcriptional control, in response to oxygen availability. Genes cox, cioAB, and ccoNOQP encode aa3, CIO, and cbb3 oxidase polypeptides, respectively. Positive regulation (+) is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation (−) is indicated by perpendicular lines. CIO, cyanide insensitive oxidase.

In Ps. aeruginosa, the Anr global transcriptional regulator plays a pivotal role in adaptation to microoxic or anoxic conditions. Anr is a homolog of E. coli Fnr and regulates expression of the enzymes required for nitrate respiration (4, 213), and of at least some of the aerobic terminal oxidases, such as the CIO oxidase and cytochrome cbb3-2 oxidase (47, 49). Recently, it has been shown that under low-oxygen conditions, Anr is involved in the repression of the CIO genes and induction of the cbb3-2 genes, while the other three terminal oxidases are not significantly regulated by Anr (Fig. 10b) (121). Similarly, in Ps. Putida, it has been shown that, under oxygen limitation, inactivation of anr led to an increased expression of the bo3-type and the CIO terminal oxidases, and to a much lower expression of cbb3-1 (equivalent to Ps. aeruginosa cbb3-2), suggesting that Anr is a transcriptional activator of cbb3-1 and a repressor of CIO genes (244).

In addition to Anr, another redox-responsive regulatory system has been proposed to be important for the regulation of terminal oxidases in Pseudomonas species, the RoxSR system. RoxSR belongs to the family of RegBA and PrrBA regulatory systems. It has been postulated in Ps. aeruginosa that the activation signal perceived by RoxS might depend on electron transport signals emerging from the oxidase cbb3-1 (47). Microarray analyses performed in Ps. putida (152) showed that a cyo mutation leads to a significant change in the transcriptome profile. They showed that the absence of bo3-type oxidase was compensated by upregulation of CIO and cbb3-1 (corresponding to cbb3-2 of Ps. aeruginosa). A regulatory system monitoring the electron flow through the bo3-type oxidase, which is similar to PrrBA activity modulation by the cbb3 oxidase, might be operative in Ps. putida.

Microarray studies have reported that RoxRS is involved in the regulation of the terminal oxidases genes in Ps. putida (78) and Ps. aeruginosa (121). In Ps. aeruginosa, RoxSR functions as a positive regulator of the putative high-affinity oxidases CIO, cbb3-1 and cbb3-2, and at the stationary phase where the dissolved oxygen concentration is low due to the high cell density, as a negative regulator of the putative low-affinity oxidase aa3 (121) (Fig. 10b). The RoxSR regulon of Ps. putida includes genes for respiratory function and maintenance of the redox balance, genes involved in sugar and amino acid metabolism, and the sulfur starvation response (78). These authors also showed that RoxSR participates in cell density signal transduction in Ps. putida. In Ps. aeruginosa, however, only a few genes related to sugar and amino-acid metabolism were identified as the members of the RoxSR regulon (121). The number of the putative RoxSR-regulated genes in Ps. aeruginosa seemed to be low compared with that in Ps. putida. These differences are presumably due to the different growth conditions used for the microarray analysis in the two Pseudomonas species.

D. Br. japonicum RegSR

The genera Allorhizobium, Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, and Sinorhizobium (Ensifer), collectively referred to as rhizobia, are members, along with other genera, of the bacterial order Rhizobiales of the α-Proteobacteria. Rhizobia are soil bacteria with the unique ability to establish a N2-fixing symbiosis on legume roots and on the stems of some aquatic legumes. During this interaction, bacteroids, as rhizobia are called in the symbiotic state, are contained in intracellular compartments called symbiosomes within a specialized organ, the nodule, where they fix N2 [reviewed in (116, 169)]. In the nodule, maintenance of nitrogenase activity is subject to a delicate equilibrium. A high rate of O2 respiration is necessary to supply the energy demands of the N2-reduction process; but, on the other hand, O2 also irreversibly inactivates the nitrogenase complex. In order to keep the steady-state concentration of free-O2 low, the cortex of nodules acts as a diffusion barrier, which greatly limits permeability to O2 [reviewed in (150)]. Oxygen is delivered to the symbiosomes by the plant O2-carrier leghemoglobin (Lb), which transports O2 at a low, but stable, concentration, allowing for the simultaneous operation of nitrogenase activity and bacteroid respiration [(66) and references therein]. N2-fixing bacteroids deal with the low levels of free O2 by inducing a high-affinity cytochrome cbb3-type oxidase [reviewed in (61)].

Similar to many other anaerobic facultative bacteria, Br. japonicum adapts to different environmental O2 concentrations by inducing multiple terminal oxidases with different affinities for O2. Br. japonicum has eight terminal oxidases, of which two are bd-type oxidases, and six are heme-copper oxidases, the latter being further divided into two quinol oxidases and four cytochrome oxidases [reviewed in (38)] (Fig. 11). Of particular interest is the fixNOQP-encoded cbb3-type oxidase, because it supports Br. japonicum aerobic respiration under free-living microoxic conditions and enables endosymbiotic Br. japonicum cells (bacteroids) to support the nitrogen fixation process. Cytochrome cbb3 oxidase has been purified from Br. japonicum (185), where the experimentally determined Km for O2 is in the order of 7 nM, a value that is consistent with its function in the bacteroid.

FIG. 11.

Aerobic respiratory chains in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. The quinone-reducing (left) and quinol-oxidizing (right) branches with terminal oxidases are shown. The coxBACF-encoded cytochrome aa3 is the predominant heme-copper oxidase for aerobic growth (gray box), and the fixNOQP-encoded cbb3-type oxidase (white box) supports respiration under free-living microoxic and under symbiotic conditions. aGene number according to RhizoBase (http://genome.kazusa.or.jp/rhizobase).

The contribution of Br. japonicum CoxG and ScoI to the biogenesis of the cbb3 oxidase has been recently investigated (38). These proteins are the respective paralogs of the mitochondrial chaperones Cox11 and Sco1 involved in the formation of CuB and CuA centers of cytochrome aa3 (12). Analyses of Br. japonicum coxG and scoI mutants revealed that disparate pathways are used for aa3- and cbb3-type oxidases biogenesis [(Bühler et al. (38)].

Oxygen concentration is the primary effector of fixNOQP expression in Br. japonicum. Under O2 limitation, the FixJ protein of the FixLJ system is phosphorylated by the oxygen-inhibitable, heme-based sensor kinase FixL (see section II.A Fig. 4b). The only known target of FixJ in Br. japonicum is fixK2, whose product, FixK2, has been shown to activate genes involved in anoxic or microoxic energy metabolism, including the fixNOQP operon (161). By using a transcriptomics approach (145), and FixK2-dependent in vitro transcription assay (148), the involvement of FixK2 as a direct transcriptional regulator of cbb3 has been demonstrated.

RegSR are members of the family of two-component regulatory redox-responsive proteins. In Br. japonicum, RegSR induces expression of the fixR-nifA operon, which encodes the NifA regulatory protein (15) (see Fig. 15). Targets of NifA include nif and fix genes, which are directly involved in nitrogen fixation, and also genes that are indirectly related to nitrogen fixation or have a unknown function in this process (83, 108, 162). Although fixNOQP genes are involved in nitrogen fixation, these genes were not identified as targets of NifA in microarray-based experiments (108). Transcription of fixR-nifA is dependent on NifA and on RegSR, respectively (Fig. 15). RegR induces expression of the fixR-nifA operon in both oxic and anoxic conditions, suggesting that RegSR responds to the overall redox state of the cell rather than to oxygen directly (15). Br. japonicum RegS possesses a highly conserved quinone binding site and a conserved redox-active cysteine, which suggests that the redox state of the membrane-localized quinone pool or the redox-active cysteine might be involved in redox sensing in Br. japonicum. However, the precise nature of the signal that is transduced by the Br. japonicum RegSR is unknown.

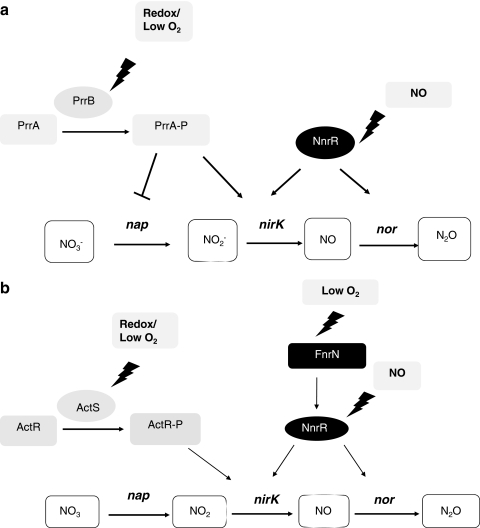

FIG. 15.

Schematic representation of the regulatory network of denitrification in Br. japonicum. FixLJ regulates fixK2 gene transcription in response to a shortage of oxygen, and FixK2 provides control of transcription on nap and nirK denitrification genes as well as the nnrR gene, whose product, in turn, activates transcription of nor genes. RegSR activates expression of fixRnifA operon presumably by sensing changes in the redox state of the cell. The NifA regulatory protein activates gene expression at very low oxygen concentrations. Control of denitrification genes by NifA has been demonstrated by our group (36). Furthermore, recent results have shown that NorC expression is significantly reduced in a Br. japonicum regR mutant (239). Sigma54 links both regulatory cascades. Positive regulation is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation is indicated by perpendicular lines.

Null mutations in the regR gene led to a dramatically decreased nitrogen fixation activity (15). Surprisingly, the phenotypic properties of regS mutants were largely indistinguishable from the wild type. Although it has been demonstrated, in vitro, that RegS is both a functional autokinase and a kinase (74), the in vivo role of RegS in RegR-mediated transcriptional activation is still unclear. In addition to fixR-nifA, a large number of novel members of the RegR regulon have been identified by transcriptomic analyses (134). Among them, a putative operon that encodes a predicted multidrug efflux system required for an efficient symbiosis specifically with soybean has been recently characterized (133).

In addition to oxygen respiration, Br. japonicum is able to obtain energy and grow from nitrate reduction to N2 through denitrification when cultured under oxygen-limiting conditions with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor. In Br. japonicum, denitrification reactions depend on napEDABC, nirK, norCBQD, and nosRZDYFLX genes encoding the nitrate-, nitrite-, nitric oxide-, and nitrous oxide reductases, respectively (see section V.C). Inactivation of Br. japonicum cycA or napC, which encode cytochromes c involved in the electron transfer through denitrification pathway, decreases the expression of Br. japonicum cbb3 oxidase during nitrate-dependent anaerobic growth (35, 37). These results suggest that a change in the electron flow through the denitrification pathway may affect the quinone redox state, leading to alterations in cbb3 expression. To further explore the possibility of redox-dependent regulation of Br. japonicum cbb3 oxidase, the effect of reduced and oxidized carbon substrates on β-galactosidase activity from a fixP’–’lacZ fusion was investigated. Levels of fixP’–’lacZ expression were largely dependent on the oxidized or reduced nature of the carbon source in the medium (37). In order to study the involvement of Br. japonicum RegR in the redox-dependent regulation of fixNOQP genes, Bueno and colleagues (37) analyzed the expression of the fixP’–’lacZ fusion in a Br. japonicum regR mutant. When cells were grown under denitrifying conditions with an oxidized carbon source, there was a significant decrease in β-galactosidase activity in the regR mutant compared with the expression levels detected in the wild-type strain. These observations suggest that Br. japonicum fixNOQP operon might be under the control of RegR. However, a whole-genome transcription-profiling analysis of the Br. japonicum regR mutant grown under microoxic conditions demonstrated that transcript levels of fixNOQP operon were not RegR-dependent (134). In recent studies from our group (Maria J. Torres et al., unpublished results), fixNOQP genes were not identified as RegR targets after transcriptomic analyses of the regR mutant grown under denitrifying conditions with succinate (an oxidized carbon source).

E. Bacilus subtilis ResDE and Rex

The endospore-forming Gram-positive bacterium Bacilus subtilis utilizes a branched ETC under aerobic conditions (250). To date, three terminal oxidases have been identified in Ba. subtilis (Fig. 12a). Both cytochromes aa3 and caa3 have been identified as heme-copper oxidases. The third oxidase has been shown to be a member of the cytochrome bd family encoded by the cydABCD operon (255). In addition, the presence of a fourth terminal oxidase of bd type, YthAB, can be predicted from the genome sequence (6).

FIG. 12.

Aerobic respiratory chains (a) and regulation of bd, aa3, and caa3 terminal oxidase expression (b) in Bacilus subtilis. In (a), the quinone-reducing and quinol-oxidizing branches with terminal oxidases induced under oxic conditions (gray boxes), and microoxic conditions (white boxes), are shown. In (b), ResDE and Fnr provide positive transcriptional control in response to oxygen availability. ResD, but not ResE, is required for transcription of cyd operon (this complex regulation is indicated with a question mark in the figure). Redox-dependent repression of cydABCD (bd oxidase) by Rex is controlled by NAD+/NADH ratio in the cells. Operons qox and cta encode the aerobic terminal oxidases aa3 and caa3. Positive regulation (+) is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation (−) is indicated by perpendicular lines.

Cytochrome bd is produced under conditions of low-oxygen tension and in cells grown in the presence of glucose. A perfect 16-bp palindromic sequence, upstream of the translation start site for cydA, was proposed as a potential operator binding site for a regulatory protein (255). Gel-shift and DNase I footprinting analyses identified YdiH as a negative regulator of cyd genes (212). YdiH is a redox sensor protein whose activity is regulated by the levels of NAD+ and NADH in the cell (104). YdiH has been renamed Rex, as it is an ortholog of Rex in Streptomyces coelicolor (31) where this redox-sensitive transcription regulator was first described. In St. coelicolor, the Rex-DNA target region (Rex operator, ROP) is an 8-bp inverted repeat located upstream of genes encoding respiratory proteins, such as heme biosynthetic enzymes, NADH dehydrogenase, Rex itself, and cytochrome bd oxidase. In Staphylococcus aureus, it has been recently demonstrated, by combining various protein–DNA interaction studies with transcriptional analyses, that Rex acts on a multitude of anaerobically induced genes (172).

Brekasis and Paget (31) showed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments that St. coelicolor Rex DNA-binding properties are influenced by the NADH/NAD+ ratio. Under aerobic conditions, raised NAD+/NADH ratio results in an increased binding of NAD+ to Rex, leading to its activation (Fig. 12b). Activated Rex binds to ROP, and inhibits the expression of several respiratory genes. However, under oxygen-limiting conditions, NADH replaces NAD+ bound to Rex, triggering a conformational change that dissociates Rex from the cyd-ROP sequence. Derepression of the cyd operon enables the cell to respire micromolar concentration of oxygen (31) (Fig. 12b). DNA binding studies of Ba. subtilis Rex with NADH or NAD+ showed that NAD+ boosted the binding activity of Rex, but that NADH seemed to have a negligible effect or a partial negative effect on DNA-binding activity (104). By contrast, in St. coelicolor, NADH completely inhibits DNA-binding activity. These data suggest that DNA-binding determinants of Ba. subtilis Rex are distinct from those of St. coelicolor Rex (31). Gyan and colleagues (104) proposed that Rex and NADH dehydrogenase together form a regulatory loop which functions to prevent a large fluctuation in the NADH/NAD+ratio in Ba. subtilis.

In order to understand the conformational modifications involved in the redox sensing by Rex, Sickmier and colleagues (220) performed X-ray studies of the Rex homolog in the thermophile Thermus aquaticus (T-Rex). Its structure comprises two main domains, an N-terminal domain that adopts a winged H-T-H fold and which most likely is the region that interacts with DNA and a C-terminal NADH binding Rossmann fold domain (220). These studies revealed that T-Rex possesses the same functional characteristics as the St. coelicolor homolog Rex, which lead to speculatation that the mechanism of repression of gene activation in response to the NADH/NAD+ redox pair is conserved among Rex family members. Small-angle X-ray scattering has been recently applied to obtain solution structures for Ba. subtilis apo B-Rex, B-Rex:NADH, and B-Rex:NAD+ showing that B-Rex presents rigid conformations for the complexes with NADH and NAD+ (251). Results from these studies indicated that the domain movements of B-Rex from the DNA bound form to the NADH (DNA-free) form could be different from the reported mechanism for T-Rex which is based on crystal structures (220).

In addition to Rex, transcription of the Ba. subtilis cytochrome bd oxidase during the transition between aerobic to anaerobic lifestyle is subjected to the action of other regulatory proteins such as Fnr, CcpA (carbon catabolite regulator protein), and the two-component system ResDE (188).

The ResD/ResE two-component signal transduction system has an important role in the regulation of both aerobic and anaerobic respiration [reviewed in (92)]. ResE is a membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase that, by responding to a redox signal(s), which have been postulated to be the redox state of intracellular MK, autophosphorylates and subsequently donates a phosphate to its cognate response regulator, ResD. It has been demonstrated that ResD activates transcription by interaction with the C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNAP (91). The ResD/ResE system activates transcription of genes involved in the respiratory pathway that transfers electrons to oxygen (under oxic conditions) or to nitrate (under anoxic conditions) as well as genes encoding transcriptional factors such as Fnr (91, 92) (Fig. 12b). Since ResDE is essential for both ctaA and ctaB expression, which are required for heme A biosynthesis, resDE mutant strains lack cytochromes aa3 and caa3. ResD also activates the genes ctaCDEF, encoding the structural proteins for cytochrome caa3 (264). By using a cydA:lacZ transcriptional fusion in resD and resE mutant backgrounds, it was shown that ResD, but not ResE, is required for the transcription of the cydA promoter, suggesting that another sensor might be involved in cydA activation by ResD. The direct interaction of ResD with the cydA promoter was found around −58 and −108 nucleotides upstream from the transcription start site by using a DNase I footprinting assay (188).

IV. Nitrate Respiration: Denitrification and Ammonification

When faced with a shortage of oxygen, many bacterial species are able to use nitrate as an electron acceptor of the respiratory chain. This switch from oxygen to nitrate respiration leads to a reduction in the ATP yield rates, but allows bacteria to survive and multiply (221). Denitrification has been defined as the dissimilatory reduction of nitrate or nitrite to a gaseous N-oxide concomitant with free energy transduction (266). The process requires four separate enzymatically catalyzed reactions:

|

For many years, it was believed that denitrification is performed exclusively by eubacteria. However, there are indications that some fungi (e.g., the pathogenic species Fusarium oxysporum) and archaea are also able to denitrify (236, 266). It has also been shown that nitrifiers also have genes involved in denitrification (44). Some bacteria such as E. coli or Ba. subtilis are able to perform nitrate respiration and release gaseous nitrogen oxides, but they do not denitrify with dinitrogen as a product. Instead, they reduce nitrate to ammonium, so-called nitrate-ammonification (45). In many species of nitrate ammonifying bacteria, there are two biochemically distinct nitrate reductases, one membrane-bound with the active site located in the cytoplasm and the other in the periplasm. These are coupled to two nitrite reductases (Nir) that provide independent pathways for nitrate reduction to ammonium (nitrate-ammonification) in the two cellular compartments. In the cytoplasm, nitrate is reduced to nitrite by a membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductase system (NarGHI):

|

The nitrite produced can then be further reduced to ammonium by a siroheme-containing Nir (NirB):

|

In the periplasm, the process involves two different enzymes, a periplasmic nitrate reductase (NapA) that reduces nitrate to nitrite and a periplasmic cytochrome c Nir that further reduces nitrite to ammonium. This process of nitrate ammonification produces nitric oxide and nitrous oxide as side-products (95, 149, 222, 225).

Products of denitrification and nitrate ammonification have manifold, mainly adverse, effects on the atmosphere, soils, and waters and thus, have both an agronomic and environmental impact (10, 105). When nitrate is converted to gaseous nitrogen by denitrifying bacteria in agricultural soils, nitrogen is lost as an essential nutrient for the growth of plants. In contrast to ammonium, which is tightly bound in soil, nitrate is easily washed out and flows to the groundwater where it (and its reduction product nitrite) adversely affects water quality. In addition, nitrogenous oxides released from soils and waters are in part responsible for the depletion of the ozone layer above the Antarctic, and in part for the initiation of acid rain and global warming (192). Among them, N2O, commonly known as laughing gas, has received special attention in the last years, because it is a powerful greenhouse gas that can persist for up to 150 years while it is slowly broken down in the stratosphere. Although N2O only accounts for around 0.03% of total greenhouse gas emissions, it has a 300-fold greater potential for global warming effects, based on its radiative capacity compared with that of carbon dioxide (10, 13, 192, 195).

A. Respiratory nitrate reductases

The first reaction of denitrification and ammonification (reactions 1 and 5), the conversion of nitrate to nitrite, is catalyzed by a membrane-bound nitrate reductase (Nar), or a Nap [reviewed in (98, 153, 154, 184, 198, 199, 201, 247)].

The Nar enzyme employs a redox loop to couple quinol oxidation with proton translocation and energy conservation, which permits cell growth under oxygen-limiting conditions (23, 221). Nap is also linked to quinol oxidation, but does not transduce the free energy in the QH2-NO3− couple into proton motive force (PMF) to synthesize ATP (221). NO3—reduction via Nap can only be coupled to free-energy transduction if the primary quinone reductase, for example NADH dehydrogenase or formate dehydrogenase, generates an H+-electrochemical gradient (221). In contrast to Nar, which has a respiratory function, Nap systems have a range of physiological functions that include the disposal of reducing equivalents during aerobic growth on reduced carbon substrates and anaerobic nitrate respiration as a part of bacterial ammonification or denitrification pathways (184).

1. Membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductase

The E. coli and Paracoccus Nar enzymes have been the focus of the most biochemical and genetic studies (reviewed in references just mentioned). Nar is a structurally defined 3-subunit enzyme composed of NarGHI (Fig. 13a) (24, 118). NarG is the catalytic subunit of about 140 kDa that contains a bis-molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide (bis-MGD) cofactor and a [4Fe-4S] cluster. NarH, of about 60 kDa, contains four additional iron-sulfur centers: one [3Fe-4S] and three [4Fe-4S]. NarG and NarH are located in the cytoplasm and associate with NarI. NarI is an integral membrane protein of about 25 kDa with five transmembrane helices and the N-terminus facing the periplasm (Fig. 13a). Nar proteins are encoded by genes of a narGHJI operon. The organization of this operon is conserved in most species that express Nar. The narGHI genes encode the structural subunits, and narJ encodes a dedicated chaperone required for the proper maturation and membrane insertion of Nar (27). E. coli has a functional duplicate of the narGHJI operon named narZYWV. The subunits of the two enzymes encoded by both operons are interexchangeable, but physiologically, NarZYWV has a function during stress response rather than anaerobic respiration per se (26, 224). A number of nar gene clusters in denitrifying bacteria also have a gene encoding a nitrogen ox anion transporter NarK that can transport nitrate into the cell and nitrite out of the cell (97, 257), a homolog of which is also found in many nitrate-ammonifying bacteria (45). A variation of the Nar system occurs in some archaea and bacteria where the NarGH subunits are on the outside, rather than the inside of the cytoplasmic membrane. These systems have thus far been less well studied biochemically, but a nitrate transporter is not needed for these systems (142).

FIG. 13.

Denitrification pathway (a) and regulation (b) in bacteria. In (a), the topological organization of denitrification enzymes is shown. The membrane-bound (NarGHI), and periplasmic, (NapABC) nitrate reductases as well as the nitrite reductases (Cu-type or cd1-type), nitric oxide reductases (cNor, qNor, and qCuANor), and nitrous oxide reductase (NosZ) are shown. (b) Regulatory network of denitrification genes in response to O2 concentration, nitrate/nitrite, and nitric oxide (NO). Positive regulation is denoted by arrows, and negative regulation is indicated by perpendicular lines. Further details are given in the text.

2. Periplasmic nitrate reductase

Nap is widespread in all classes of denitrifying and non-denitrifying proteobacteria [reviewed in (98, 153, 154, 184, 198, 199, 201, 247)]. The best-studied Nap enzymes were isolated from Paracoccus pantotrophus E. coli, Rho. sphaeroides, and Desulfovibrio desfuromonas (5, 64, 115). Nap is commonly a 2-subunit enzyme composed of the NapAB complex located in the periplasm and associates with a transmembrane NapC component (Fig. 13a). The catalytic subunit NapA contains the bis-MGD cofactor at its active site and an FeS center. NapB is diheme cytochrome c552, and NapC is a c-type tetra-heme membrane-anchored protein that is involved in the electron transfer from the quinol pool to NapAB (43, 207). Mono-subunit forms of NapA also occur, which may interact with small FeS proteins as well as cytochromes (114, 115, 140).

In contrast to the nar operon, the nap operons present considerable heterogeneity in gene composition as well as in ordering. Eight different genes have been identified as components for operons that encode Naps in different organisms (199). Except for Shewanella oneidensis, Wollinella succinogenes, Desulfobacterum hafniensi, and C. jejuni, which lack napB or napC, all operons studied thus far have the napABC genes in common. The remaining napDEFKL genes encode for different proteins that are not directly involved in the nitrate reduction. NapD is a cytoplasmic protein that acts as a chaperone. NapF is a cytoplasmic iron–sulfur containing protein with four loosely bound [4Fe–4S] clusters, and is thought to participate in the assembling of the iron–sulfur cluster of NapA (164, 170). The napEKL genes encode for proteins with so far unknown functions. In E. coli, the nap operon includes napGH genes encoding a periplasmic and an integral membrane protein with [4Fe–4S] clusters. NapH and NapG interact, making an electron transfer supercomplex that can channel electrons from both menaquinol and ubiquinol to NapA (32, 33).

B. Other enzymes in bacterial denitrification

The enzymes involved in denitrification are nitrate-, nitrite-, nitric oxide-, and nitrous oxide reductase, encoded by nar/nap, nir, nor, and nos genes, respectively. A scheme of the denitrification reactions is shown in Figure 13a. Comprehensive reviews covering the physiology, biochemistry, and molecular genetics of denitrification have been published elsewhere (11, 16, 110, 125, 199, 247, 248, 266).

1. Nitrite reductases

In denitrifying bacteria, two types of respiratory Nir have been described: the NirS cd1 nitrite reductase, a homodimeric enzyme with hemes c and d1, and the NirK, a copper-containing Nir [reviewed in (202, 203, 246, 247)]. Both are located in the periplasmic space, and receive electrons from cytochrome c and/or a blue copper protein, pseudoazurin via the cytochrome bc1 complex (Fig. 13a). They catalyze the one-electron reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide. Neither of the enzymes is electrogenic.

The cd1-type nitrite reductase (cd1Nir) is a homodimer, and each monomer carries a small heme c binding domain and a larger heme d1-binding domain. Electrons are transferred from the electron donor via the heme c of NirS to heme d1, where nitrite binds and is reduced to nitric oxide (202). The nirS gene encoding the cd1-Nir polypeptide is part of a nir gene cluster. The best-characterized clusters are those from the denitrifying species Ps. aeruginosa (nirSMCFDLGHJEN), Pa. denitrificans (nirXISECFDLGHJN), and Ps. stutzeri (nirSTBMCFDLGH and nirJEN, the two clusters being separated by a part of the nor gene cluster encoding nitric oxide reductase [Nor]).

Cu-type nitrite reductases (CuNir) are homotrimeric complexes harboring three type I copper centers, and three type II copper centers, which form the active site. Nitrite binds to the copper ion in the type II center, replacing an exogenous ligand (water or chloride), and by electron transfer from the type I copper site, nitrite is reduced to nitric oxide. The nirK gene encodes the CuNir (203).

2. Nitric oxide reductases

To date, three types of Nor have been characterized, and they are classified according to the nature of their electron donor as c-type nitric oxide-reductase (cNor), qNor, and qCuANor [reviewed in (59, 247, 248, 267)]. As a unique case, the Nor of Ros. denitrificans is similar to cNor, but differs in that it contains copper (143). The best-studied Nor is the cNor that uses membrane or soluble c-type cytochromes or small soluble blue copper proteins (azurin, pseudoazurin) as physiological electron donors. The qNor uses quinol or menaquinol as electron donors and it is found not only in denitrifying archaea and soil bacteria, but also in pathogenic microorganisms that do not denitrify (60). The qCuANor has thus far been found only in the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus azotoformans (230). This enzyme is bifunctional using both menahydroquinone (MKH2) and a specific c-type cytochrome c551 as electron donor. It was suggested that the MKH2-linked activity of qCuANor serves detoxification and the c551 pathway has a bioenergetic function.

The cNor is an integral membrane enzyme harboring two subunits, NorC with a heme c group and NorB containing hemes b and a non-heme iron (Fig. 13a). Electron transfer from donor molecules to cNor is mediated by the cytochrome bc1 complex and a soluble cytochrome c or pseudoazurin (174). Electrons are transferred to the heme c in subunit II and then via the heme b to the active site. There, two molecules of nitric oxide are reduced. The molecular mechanism of the NO reduction by Nor has been extensively studied through chemical, biochemical, and physicochemical techniques (80, 81, 252). The crystal structure of Nor from Ps. aeruginosa has been recently solved (112). Although the overall structure of Nor is closely related to the heme copper oxidases, neither the D- nor K-proton pathway, which connect the HCO active center to the intracellular space, was observed. This confirmed early studies with NorCB in intact cells of Rho. capsulatus which showed that it was not a proton pump or electrogenic (196). Site-specific mutagenesis has suggested that protons required for the Nor reaction are probably provided from the periplasmic side of the membrane via a channel that involves conserved glutamate residues (41, 85, 86, 237).

cNOR is encoded by the norCBQD operon. The norC and norB genes encode subunit II and subunit I, respectively. The norQ and norD genes encode proteins essential for activation of cNor. Some more specialized denitrifiers have additional norEF genes, the products of which are involved in maturation and/or stability of Nor activity (107).

3. Nitrous oxide reductase