Abstract

Background and Objectives

Medical insurance claims (MIC) data are one of the largest sources of outcome data in the form of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. We evaluated the validity of the ICD codes from the Korean National MIC data with respect to the outcomes from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the Korean Heart Study.

Subjects and Methods

Baseline information was obtained from health examinations conducted from 1994 to 2001. Outcome information regarding the incidence of AMI came from hospital admission discharge records from 1994 to 2007. Structured questionnaires were sent to 98 hospitals. In total, 107 cases of AMI with ICD codes of I21- (93 men, 26-73 years of age) were included in the final analyses. ICD code accuracy and reliability (kappa) for AMI were calculated.

Results

A large number of AMI cases were from hospitals located in the Seoul area (75.9%). The accuracy of AMI was 71.4%, according to World Health Organization criteria (1997-2000, n=24, kappa=0.46) and 73.1% according to the European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology (ESC/ACC) criteria (2001-2007, n=83, kappa=0.74). An age of 50 years or older was the only factor related to inaccuracy of codes for AMI (odds ratio, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-17.7) in patients diagnosed since January 2001 using ESC/ACC criteria (n=83).

Conclusion

The accuracy for diagnosing AMI using the ICD-10 codes in Korean MIC data was >70%, and reliability was fair to good; however, more attention is required for recoding ICD codes in older patients.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Validity, Reliability, International Classification of Diseases

Introduction

The importance of valid data has increased due to the high impact of cardiovascular diseases on mortality and morbidity. Medical insurance claims (MIC) data are one of the largest sources of outcome data in the form of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes.1) Because enrollment is mandatory for all Koreans, the Korean national health insurance system covers nearly all of the country's population (96.3% in 2007) with the exception of some medical assistance beneficiaries. If the validity of MIC data is acceptable for research purposes, it can be used as a comprehensive and economical source of outcome information.

International Classification of Diseases codes have been used in research for years; however, accuracy issues have been raised in recent studies. Questions regarding validity have been suggested as a result of ambiguities and inconsistencies in ICD-coded diagnoses.2) Coding errors are also regarded as an issue with regards to data reliability.3) Despite these concerns, the reported accuracy of ICD codes appeared to be acceptable in previous reports. In Korea, the accuracy rate of ICD codes for cerebrovascular disease was 83% for 425 men, according to insurance claims.4) However, the accuracy of ICD codes for cardiovascular disease is not well-known. Particularly, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), a fatal disease, has doubled in the past 11 years (1997-2007).5) Therefore, in this study we evaluated the validity of ICD codes for AMI according to Korean national MIC data.

Subjects and Methods

Study sample

The subjects were participants in the prospective cohort Korean Heart Study, which was developed to establish a cardiovascular diseases prediction model. The initial Korean Heart Study population consisted of 476529 subjects who underwent health examinations at 19 health examination centers in Korea from 1993 to 2004. Among the initial subjects, 673 cases with International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision codes (ICD-10) of cardiovascular disease outcomes (I20-I25, I50) on MIC were selected. Among the 482 responses, 107 cases of AMI with the ICD codes of I21- (I21, I210-I219) were included in the final analyses (93 men, 26-73 years of age). Data from three cases could not be collected due to hospital closures and/or mistakes in patient identification.

The outcome variable investigated was incidence of AMI in hospital admission discharge records from 1994 to 2007 (median follow-up duration, 9.4 years). Outcomes were ascertained from health insurance claim data from the National Health Insurance Corporation.6),7)

Informed consent from each study participant was obtained during routine health examinations. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Human Research of University.

Data collection

Diagnosis determination (definition)

The ICD-10 code for AMI was I21-. The event validation committee of the Korean Society of Cardiology (KSC) also defined the diagnostic criteria for AMI according to the joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology (ESC/ACC) criteria of 20008) and World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.9) Because the ESC/ACC criteria were introduced in 2000, AMI was defined by WHO criteria until December 2000 (24 cases) and by ESC/ACC criteria since January 2001 (83 cases). The cut-off date was determined as above due to the possibility of a time lag between the publishing point of the new criteria and awareness of the new criteria to the majority of physicians.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire and survey were performed in cooperation with the KSC to improve the quality and rate of responses. To investigate the cardiovascular disease evidence reported in medical records, a structured questionnaire was drafted by a cardiologist using well-known diagnostic criteria by reviewing previous reports.8-10) The event validation committee of the KSC, consisting of 23 cardiologists in teaching hospitals, reviewed the questionnaire. After input from the committee, two cardiologists and a family physician tested and updated the questionnaire through a pilot study at one hospital with 20 cases.

The final revised questionnaire was sent directly to the cardiology departments of 98 hospitals, which made the diagnosis using the ICD codes. If an individual cardiologist involved in the case had left the hospital, other staff or cardiologists were requested to answer the questionnaire. They were required to complete the questionnaire according to the medical records kept at their hospitals. A detailed introduction to the study purpose and guidelines for completing the questionnaire were provided.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and hospital characteristic data, including the num-ber of hospitals, were collected and analyzed according to area, initial cases, returned cases, return rate, hospital type, questionnaire respondent, and ICD code administrator. The proportion of ICD codes per subject was calculated.

The accuracy of ICD codes for AMI was calculated using the following formula4): the number of MI patients according to the diagnostic criteria/the number of patients with ICD-10 codes of I21 - in the MIC data among patients with sufficient medical records data×100 (%).

Kappa values were calculated to assess the reliability between each of the AMI criteria and ICD codes.

Potential factors related to the inaccuracy of an AMI diagnosis were assessed by logistic regression analysis.

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was determined to be p<0.05.

Results

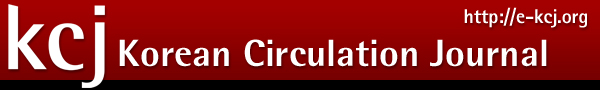

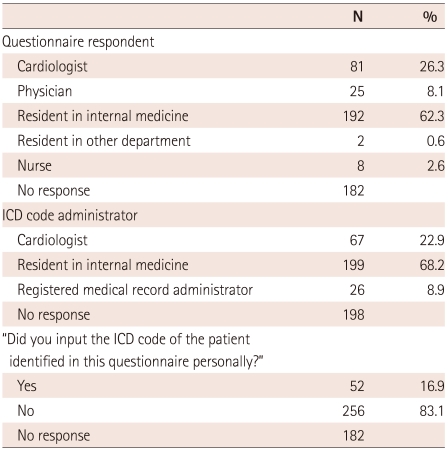

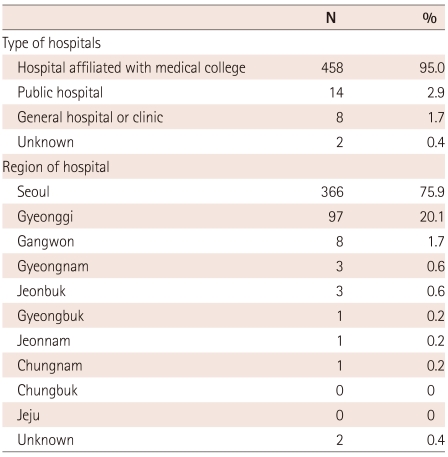

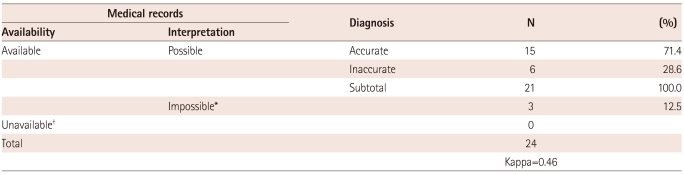

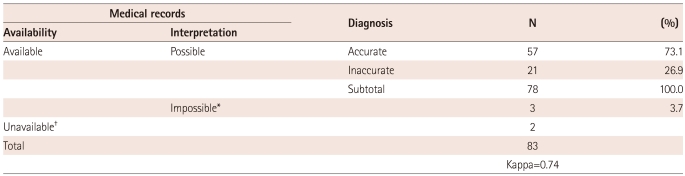

Among the 673 mailed questionnaires, we received 482 responses (71.6%). The most common respondents were resident trainees in internal medicine departments (Table 1). Among the respondents, 95.0% were working at hospitals affiliated with medical colleges. A large number of the cases (75.9%) were from hospitals located in the Seoul area (Table 2). AMI, defined as I21, I210-I219 on the MIC ICD-10 codes, was reported in 107 cases (93 men, 26-73 years of age). Mean age (standard deviation) of the patients with AMI was 49.5 (10.1) years. Unspecified forms of AMI (I219) accounted for 48.6% (Table 3). The accuracy of AMI was 71.4%, according to the WHO criteria (1997-2000, n=24, kappa=0.46) and 73.1% according to ESC/ACC criteria (2001-2007, n=83, kappa=0.74), after excluding unavailable cases (Table 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents in the event validation project

ICD: International Classification of Diseases

Table 2.

Number of cases based on the characteristics of the hospitals participating in the event validation project (n=482)

Table 3.

Subgroup of acute myocardial infarction (I21-) based on ICD-10 code frequency

MI: myocardial Infarction, ICD: International Classification of Diseases

Table 4.

Accuracy of ICD codes for acute myocardial infarction using the WHO criteria in medical insurance claims data among ICD-10 codes I21- (1997-2000)

*Due to insufficient data to determine the accuracy of ICD coding for AMI, †Due to closing of hospitals, failure to find medical records, or patient misidentification. ICD: International Classification of Diseases

Table 5.

Accuracy of ICD codes for acute myocardial infarction using ESC/ACC criteria for medical insurance claim data with an ICD-10 code of I21- (2001-2007)

*Due to insufficient data to determine the accuracy of ICD coding for AMI, †Due to the closing of hospitals, failure to find medical records, or patient misidentification. ICD: International Classification of Diseases, ESC/ACC: European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology

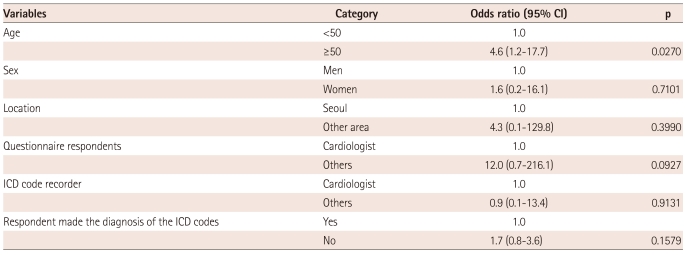

An age of 50 years or older was the only factor related to AMI inaccuracy (odds ratio, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-17.7, p=0.0270) after adjusting for gender, hospital location, respondents, ICD code recorder, and respondents who made the diagnosis related to the ICD codes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Potential variables related to the inaccuracy of ICD codes for acute myocardial infarction among patients diagnosed since January 2001 by ESC/ACC criteria (n=83)

CI: confidence interval, ICD: International Classification of Diseases, ESC/ACC: European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology

Discussion

The accuracy and reliability of AMI diagnoses in the Korean Heart Study was evaluated to assess validity. The accuracy of AMI was 71.4% (WHO criteria, 1997-2000) to 73.1% (ESC/ACC criteria, 2001-2007). Reliability between each of the AMI criteria and ICD codes was good to fair in terms of the kappa values (0.46 or 0.74) according to the suggestion of Fleiss that values >0.75 indicate excellent reliability, those 0.40-0.75 indicate fair to good, and <0.40 indicate poor.11)

The importance of MIC data has been growing, particularly in epidemiological studies due to the huge population included.12) However, issues regarding the reliability of MIC data have been raised continuously. Hospitals may record codes incorrectly in some cases due to reimbursement issues.13) Admission duration and the presence of complex co-morbidities also add to confusion in understanding the discharge data.14),15) There are several known reasons associated with coding errors, including misspecification, miscoding, and re-sequencing or substitution of the major diagnosis with a secondary diagnosis for the purpose of reimbursement.16) The ICD codes alone include ambiguities and inconsistencies.2)

Although the ICD-coding system has certain limitations, the usefulness of the coding has also been reported, and it has been used in various studies to date. In an intervention study, the reliability of ICD-10 coding was assessed among three groups of students, staff, and coding specialists, and concordance results were fair to moderate.17)

Studies on the reliability of ICD codes in the field of cardiovascular research have been reported. Validity of ischemic heart disease coding was evaluated in Canada where physician service claims and discharge records using the ICD-9 code were concordant in 69.3% of AMI cases.18)

In the Republic of Korea, the National Insurance System covers nearly all of the population. Claims and payments are handled by an online electronic system. Some conflicts occur with the payment system between the insurance payer and hospitals, so we could not exclude the possibility of systematic miscoding; however, efforts to reduce coding errors have been introduced by the payer.

Several findings regarding stroke and diabetes have been obtained among reports on the accuracy of ICD codes in Korea. Park et al.4) reported an 83% accuracy for a cerebrovascular diseases diagnosis based on ICD codes in 425 cases among Korean men in 2000. In the National Diagnosis Related Group Validation Study, the accuracy of mixed diseases was 79.2%.13) In the diabetes epidemiology report in Korea, the accuracy of admitted cases was 87.2%, and that of outpatients was 72.3%.19) These results for other diseases seem to be comparable with our AMI accuracy results. It has been suggested that the accuracy of various mixtures of many diagnoses cannot be summarized or generalized due to the unique clinical situations and specific conditions of each disease.20),21) In an evaluation of the appropriateness of AMI diagnostic coding in Boston, 41.7% of the cases failed to qualify in teaching hospitals because of inappropriate coding results, whereas the number was only 9.1% in non-teaching facilities.22) Many of our participants were from teaching hospitals, and the coding results were acceptable. However, the differences in qualification status among hospitals may not be comparable among countries due to huge variations in medical care systems.

In this study, we used WHO and ESC/ACC criteria to assess the AMI diagnoses. ESC/ACC criteria were introduced in 2000 and include creatine kinase MB.8) The WHO criteria, which have also been widely used, was the core method in the Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease project.9),10)

Several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. We could not collect any information regarding the reasons for coding errors or on the various coding pathways in multiple hospitals. For example, the possibility of accidental AMI coding rather than sudden death cannot be excluded. Questionnaires were sent instead of a direct review of the medical records. The number of cardiologists or staff who directly input the ICD codes was small, and the number of no responses was large. Many of the participant hospitals were located in city areas and were teaching hospitals, so we could not expand our results to all hospitals or clinics. We evaluated all of the AMI cases using our approach, but they were not recruited randomly. We had a relatively small number of subjects, particularly of women (n=14, 13.1% of the 107 AMI cases). The reliability of the AMI diagnosis was fair to good regardless of these potential differences among our samples. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias, because the participants were spontaneous examinees of health examination centers, although data from similar health examination centers has been used in previous cardiology studies.23),24)

In conclusion, the accuracy of the AMI diagnosis using ICD-10 codes in Korean MIC data was >70%, and reliability was good to fair. An age of 50 years or older was the only factor related to inaccuracy of AMI diagnoses; therefore, more attention is required when re-coding ICD data of older patients. Further studies should be performed with regard to the validity of AMI MIC data and other cardiovascular diseases using a larger group.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Seoul R & BD Program, Republic of Korea (10526), a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R & D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A000385), and Pfizer Inc.

The authors are indebted to the event validation committee of the KSC for their development of the questionnaire and for data collection: Byung Ok Kim, Inje University College of Medicine; Joo-Young Yang, NHIC Ilsan Hospital; Jong-Seon Park, Yeungnam University Hospital; Jei Keon Chae, Chonbuk National University Medical School; Young Keun Ahn, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School; Myeong-Chan Cho, Chungbuk National University; Junghan Yoon, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine; Seung-Jea Tahk, Ajou University School of Medicine; Chang Gyu Park, Korea University Guro Hospital; Seung-Jae Joo, Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University; Cheol-Ho Kim, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Cardiovascular Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine; Taek Jong Hong, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Pusan National University; Young Dae Kim, Cardiology Department, Dong-A University Medical Center; In-Whan Seong, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungnam National University; Ki-Hoon Han, Divisions of Cardiology, Pulmonology and Cardiac Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine; Tae Hoon Ahn, Division of Cardiology, Heart Center, Gachon University Gil Medical Center.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.International classification of diseases and related health problems: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surján G. Questions on validity of international classification of diseases-coded diagnosis. Int J Med Inform. 1999;54:77–95. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsia DC, Ahern CA, Ritchie BP, Moscoe LM, Krushat WM. Medicare reimbursement accuracy under the prospective payment system, 1985 to 1988. JAMA. 1992;268:896–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JK, Kim KS, Kim CB, et al. The accuracy of ICD codes for cerebrovascular diseases in medical insurance claims. Korean J Prev Med. 2000;33:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong JS, Kang HC, Lee SH, Kim J. Long-term trend in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction in Korea: 1997-2007. Korean Circ J. 2009;39:467–476. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2009.39.11.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HC, Kang DR, Nam CM, et al. Elevated serum aminotransferase level as a predictor of intracerebral hemorrhage: Korea Medical Insurance Corporation Study. Stroke. 2005;36:1642–1647. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000173404.37692.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jee SH, Sull JW, Park J, et al. Body-mass index and mortality in Korean men and women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:779–787. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project: registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation. 1994;90:583–612. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochholzer W, Buettner HJ, Trenk D, et al. New definition of myocardial infarction: impact on long-term mortality. Am J Med. 2008;121:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleiss JL. Reliability of measurements. In: Fleiss JL, editor. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: Wiley; 1986. pp. 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watzlaf VJ. The medical record as an epidemiological database. Top Health Rec Manage. 1987;7:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsia DC, Krushat WM, Fagan AB, Tebbutt JA, Kusserow RP. Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective-payment system. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:352–355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802113180604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jencks SF, Williams DK, Kay TL. Assessing hospital-associated deaths from discharge data: the role of length of stay and comorbidities. JAMA. 1988;260:2240–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenfield S, Aronow HU, Elashoff RM, Watanabe D. Flaws in mortality data: the hazards of ignoring comorbid disease. JAMA. 1988;260:2253–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsia DC, Ahern CA, Ritchie BP, Moscoe LM, Krushat WM. Medicare reimbursement accuracy under the prospective payment system, 1985 to 1988. JAMA. 1992;268:896–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stausberg J, Lehmann N, Kaczmarek D, Stein M. Reliability of diagnoses coding with ICD-10. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawson NS, Malcolm E. Validity of the recording of ischaemic heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the Saskatchewan health care datafiles. Stat Med. 1995;14:2627–2643. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780142404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JW. Analysis in the incidence and hospital use of Diabetes using medical insurance claim data. Diabetes in Korea. 2005:42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iezzoni LI, Moskowitz MA. Clinical overlap among medical diagnosis-related groups. JAMA. 1986;255:927–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher ES, Whaley FS, Krushat WM, et al. The accuracy of Medicare's hospital claims data: progress has been made, but problems remain. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:243–248. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iezzoni LI, Burnside S, Sickles L, Moskowitz MA, Sawitz E, Levine PA. Coding of acute myocardial infarction: clinical and policy implications. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:745–751. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D, Choi SY, Choi EK, et al. Distribution of coronary artery calcification in an asymptomatic Korean population: association with risk factors of cardiovascular disease and Metabolic syndrome. Korean Circ J. 2008;38:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HJ, On YK, Sung JD, et al. Risk factors for predicting new-onset atrial fibrillation in persons who received health screening tests. Korean Circ J. 2007;37:609–615. [Google Scholar]