Abstract

Periodontal diseases are multi-factorial in etiology, and bacteria are one among these etiologic agents. Thus, an essential component of therapy is to eliminate or control these pathogens. This has been traditionally accomplished through mechanical means (scaling and root planing (SRP)), which is time-consuming, difficult, and, sometimes, ineffective. From about the past 30 years, locally delivered, anti-infective pharmacological agents, most recently employing sustained-release vehicles, have been introduced to achieve this goal. This systematic review is an effort to determine the efficacy of the currently available anti-infective agents, with and without concurrent SRP, in controlling chronic periodontitis. Four studies were included, which were all randomized controlled trials, incorporating a total patient population of 80, with 97 control sites and 111 test sites. A meta-analysis completed on these four studies including SRP and local sustained-release agents compared with SRP alone indicated significant adjunctive probing depth (PD) reduction for 10% Doxycycline hycylate (ATRIDOX), minocycline hydrochloride (ARESTIN), tetracycline hydrochloride (PERIODONTAL PLUS AB), and chlorhexidine gluconate (PERIOCHIP). Essentially, all studies reported substantial reductions in gingival inflammation, plaque scores, and bleeding indices, which were similar in both the control and the experimental groups. Use of antimicrobial sustained-release systems as an adjunct to SRP does not result in significant patient-centered adverse events. Local drug delivery combined with SRP appears to provide additional benefits in PD reduction compared with SRP alone.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine, chronic periodontitis, doxycycline, drug therapy, local drug delivery agents, meta-analysis, minocycline, tetracycline, therapeutic use

BACKGROUND

Chronic periodontitis is an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment loss, and bone loss, and is characterized by periodontal pocket formation and/or recession of the gingiva.[1] The inflammatory periodontal diseases are widely accepted as being caused by bacteria associated with dental plaque.[2] Since the early 1970s, the quest to identify bacterial specificity in periodontal disease became the prominent area of investigation. This led Loesche in 1976 to introduce the specific plaque hypothesis, suggesting that specific bacteria causes specific forms of periodontal diseases.[3]

Both non surgical and surgical therapy are applicable in the treatment of periodontal disease. However, mechanical therapy itself may not always reduce or eliminate the anaerobic infection at the base of the pocket, within the gingival tissues, and in both structures inaccessible to periodontal instruments.[4] To overcome this,systemic and local drug delivery of antimicrobials was initiated to enhance nonsurgical therapy by serving as an adjunct to scaling and root planing Adverse effects such as drug toxicity, acquired bacterial resistance, drug interaction, and patient's compliance limit the use of systemic antimicrobials.[5]

Therefore, to override these shortcomings, local deliveries of antibacterial agents into periodontal pockets have been extensively studied. It was Dr. Max GoodSon in 1979 of the Forsyth Dental Research Centre who championed and developed the concept of controlled release-Local Drug Delivery (LDD).[6] This mode of drug delivery avoids most of the problems associated with systemic therapy, limiting the drug to its target site and hence achieving a much higher concentration.[7] The fact that periodontal diseases are localized to the immediate environment of the pocket make the periodontal pocket a natural site for treatment with local sustained-delivery systems. This forms the basis of LDD devices in the treatment of periodontitis. Antibacterial agents have thus become an integral part of the therapeutic armamentarium.

Systematic review is a thorough, comprehensive, and explicit way of interrogating the literature. It typically involves various steps that include asking an answerable question, identifying one or more data base to search, developing an explicit search strategy, selecting titles, abstracts, and manuscripts based on explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria, and abstracting data in a standardized format. Meta-analysis is a statistical procedure that integrates the results of several independent studies considered to be combinable. It is a statistical approach to combine data derived from systematic review and it gives a more objective appraisal of the evidence than traditional narrative reviews. It provides a more precise estimate of a treatment effect as given by Egger et al. Therefore, this is a combined statistical data of four studies carried out with similar inclusion and exclusion criteria.

RATIONALE

This meta-analysis evaluates the literature-based evidence in an effort to determine the efficacy of the currently available anti-infective agents, with and without concurrent scaling and root planing (SRP), in controlling chronic periodontitis. Locally delivered anti-infective pharmacological agents, specifically antibiotics, are generally administered in doses much lower than that required with systemic administration, reducing the risk of serious systemic side-effects associated with the drug. It is important, therefore, to determine the usefulness of these drugs in periodontal therapy in an effort to weigh the relative benefits and risks associated with their use.

FOCUSED QUESTION

The question addressed in this systematic review was “In patients with chronic periodontitis what is the effect of local controlled-release anti-infective drug therapy with or without SRP on changes in clinical outcomes?”

SEARCH PROTOCOL

The search strategy followed was the Medline data base and hand searching. These data bases were searched using controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and free text words. All references cited in the included trials were checked. The clinical reports published only in the English language were considered. Hand searching was performed for studies carried out in the Department of Periodontics, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere. The studies were examined by four independent viewers to select studies relevant to the specific question posed in this review. Based on these four studies, possible relevance was obtained.

Inclusion criteria

Studies included randomized controlled clinical trials (RCT) performed in the Department of Periodontics, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, with at least a 3-month-long follow-up. All the studies were of a split-mouth design. Therapeutic interventions had to include (1) SRP alone and (2) local anti-infective drug therapy and SRP. The included studies had measures of variation for probing depth (PD), bleeding index (BI), and plaque index (PI) for both the test and the control groups.

Exclusion criteria

Reasons for study exclusion, in addition to the absence of the inclusion criteria listed above, included daily rinsing with antibacterial mouth rinses or history of taking any antibiotics, or had unclear descriptions of randomization procedures, examiner masking, or concomitant therapies, or those that included studies on smokers.

Outcomes

The primary and required outcome measures for study selection were PD, measured from the gingival margin to the depth of probe penetration. Secondary outcomes included measurements of plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation, and bleeding on probing (BOP). All studies were examined for reports of adverse events such as post treatment complications of pain, infection, and allergic reactions.

Data collection and analysis

Where available in individual papers, study mean and variance values for PD were taken directly from the text or tables. For groups of related studies, differences between control and experimental PD, BOP, and PI were expressed as weighted millimeter averages, where the weight was a function of the sample size. Secondary outcomes like plaque scores and BOP values were expressed as weighted mean percentage changes in index scores, where the weight was a function of the sample size. Thus, outcome values reported in this review may vary slightly from those given in individual studies.

Analysis of summary effects between SRP alone and with anti-infective agents was conducted essentially as described by Fleiss. The effect size between the control and the experimental treatment approaches was expressed as a weighted summary mean with associated 95% confidence intervals for the effect, where the weight was a function of variance for PD, and a function of sample size for BOP and PIs. Effect size represents the magnitude of impact of intervention on an outcome or degree of association between two variables.

MAIN RESULTS

Characteristics of the included studies

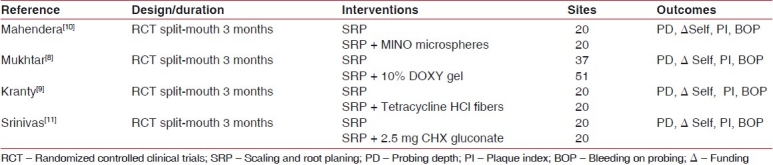

Table 1 lists the four included studies and provides an overview of the experimental methods and study duration, therapeutic interventions, sample sizes, outcome measures, and primary source of funding.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies by design and agent vehicle

All the studies employed a manual periodontal probe to measure the PD from the gingival margin. Moreover, indices used to measure BOP and PI were the same in all the studies.

All included studies provided a description of randomization procedures for assignment of patients to therapeutic arms, and all allocations were made by the study investigators based on a described randomization scheme rather than by clinical judgments of appropriate therapeutic interventions for particular sites. All included studies provided a description of examiner masking such that outcome assessors were unaware of the allocation of the therapeutic interventions.

All the patients in each RCT were randomly allocated into two groups: the control and the test groups. In the control group, only SRP was performed, whereas in the test population, LDD was used as an adjunct.

RESULTS

Scaling and root planing alone

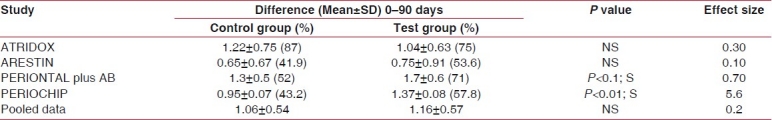

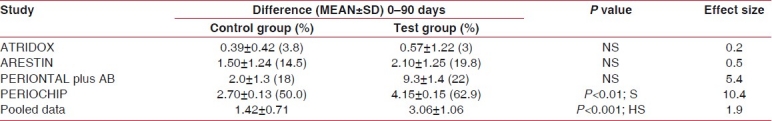

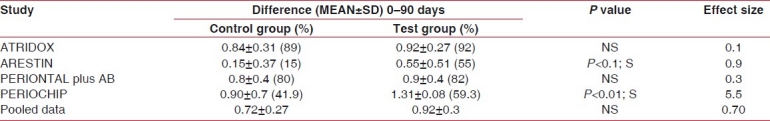

We assessed the effects of SRP in the included studies with separate patient groups treated by SRP alone.[8–11] Adjusted mean reduction in PD from the baseline examination before SRP to the final examination was 1.42 mm. Significant reductions in the weighted mean scores were also observed for percentage BOP (mean±SD = 0.72±0.27) and plaque scores (mean±SD = 1.06±0.54) from baseline with SRP alone [Tables 2–4].

Table 2.

Plaque index

Table 4.

Probing pocket depth

Table 3.

Gingival index

Adjunctive sustained-release studies

On the other hand, the relative effects on PD reduction from the four studies of treatment with SRP plus local sustained-release agents were compared with SRP alone. Weighted mean millimeter differences for PD reduction with adjunctive therapy was 3.06±1.06 and mean reduction scores for BOP (mean±SD) was 0.92±0.3 and the plaque score was (mean±SD) 1.16±0.57.

When relative effects of treatment with SRP plus local sustained-release agents were compared with SRP alone, significant reduction in PD was found with adjunctive PERIOCHIP use and the effect size was 10.4, which is very high, indicating a very large additive effect of using PERIOCHIP as an adjunct to SRP in PD reduction of chronic periodontitis cases. Similarly, the effect size for the TET fiber group was 5.4, which was again very large. MINO microspheres and ATRIDOX were reported to have moderate effect sizes of 0.5 and 0.2.

Overall, the effect size after meta-analysis of pooled data revealed a value of 1.9, which shows a large effect of adjunctive therapy of local drug delivery with SRP in PD reduction in chronic periodontitis subjects.

On comparison between the effects of adjunctive anti-infective therapy with SRP alone in these four studies, percent reductions in plaque scores and BOP were not significant for the pooled data but effect size on PI was mild (0.2) and for BOP was moderate (0.7), which proves the additive effect of adjunctive therapy in reducing bleeding and plaque scores in chronic periodontitis cases.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that diseases caused by microbial biofilms, such as chronic periodontitis, are extremely difficult to treat. Dental biofilms are difficult therapeutic targets as they are not easily disrupted.[12] In a non sterile environment such as the mouth, it is virtually impossible to completely prevent their formation. The scientific rationale for adding locally applied anti-infective agents to SRP is that certain broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents can theoretically reduce the number of subgingival bacteria left behind after SRP. Although mechanical removal or disruption of subgingival biofilms by SRP is usually an effective therapeutic approach for the treatment of chronic periodontitis, it does not sterilize the subgingival environment. Almost immediately after SRP, bacteria left behind begin to recolonize the subgingival environment to form a new biofilm.[13]

SRP alone in the studies included in this review resulted in statistically significant reductions in PD and improvements in measures of BOP and plaque scores. These findings are consistent with those summarized by Cobb in his 1996 review.[1–3,14] In the current systematic review, a sample size-adjusted mean reduction in PD of pooled data was found to be 1.42 mm following SRP alone. In view of the sample size-weighted pre treatment average PD, this amount of PD reduction is consistent with that reported in previous studies where the initial PDs were of the same severity.[13–19]

However, the sample size-adjusted mean reduction in PD of pooled data was found to be 3.06 mm following adjunctive treatment with local drug delivery.

When the data was pooled for all studies and meta-analysis was performed on the probing pocket depth, this was found to be decreased in the test group, which was highly significant. Effect size of pooled data showed a value of 1.9, which showed a very large effect of administering local drug delivery as an adjunct to SRP. Similar studies by Pavia et al. and Hanes et al. separately reported similar findings with their meta-analyses.[20,13] This supports the literature that association of mechanical and antimicrobial effect can be more effective than traditional treatment alone.[13,20–24]

It was found that some sustained-release antimicrobial agents combined with SRP provided a relatively small but statistically significant reduction in PD compared with SRP alone. Proye et al. reported that much of the PD reduction following SRP may be primarily due to gingival recession.[25]

When comparisons were made between the control and the test groups at different intervals of time, the BI was found to be decreased in all the groups, but a statistically significant difference between test and control groups was found in case of MINO micro spheres and CHX chip.[8–11] These results were concomitant with a significant benefit of 2% minocycline as an adjunct to SRP treatment on BOP, as reported by Grac et al.[21] Paolantonio et al. reported that the percentage of sites positive for BOP was similar between the treatments at each time point,[22] whereas Grisi et al. reported that BOP was significantly reduced in the control group.[26]

When the data was pooled for all studies and a meta-analyses was performed, the BI decreased in the test group, which was not statistically significant, but the effect size was moderate (0.7).

Similar results were given by Hanes et al. in their systematic review, which states that all studies reported substantial reductions in gingival inflammation and BIs, which were similar in both the control and the experimental group.[13] Emingil, in 2006, reported decreased bleeding scores over a 12-month period.[24]

The possible cause for these results is that Gingival Bleeding Index GBI relates to the inflammatory status. There is decrease in inflammatory markers like prostaglandin E2 and MMP 8 with LDD, which is possibly due to modulation of the host response, which was probably the cause of decreased BI in the test group.[25]

When comparisons were made between the control and the test groups at different intervals of time, the PI was found to be decreased in all the groups, but a statistically significant difference between the test and the control group was found in case of periodontal plus AB and periochip.

These results were concomitant with a significant benefit of SRP + CHX chip treatment on the subgingival microbiota as reported by Paolantonio et al.[22] whereas Cosyn et al. who performed a study using chlorhexidine varnish as an adjunct to SRP in the treatment of chronic periodontitis reported no difference in plaque scores between the two groups.[27] When the data was pooled for all studies and a meta-analysis was performed, the PI was found to be decreased in the test group, but was not statistically significant, and the effect size was also mild (0.2). Similar studies were performed by Cosyn et al.,[27] who reported similar results in their systematic review, whereas Paolantonio et al. reported decreased plaque scores with LDD.[22]

The possible cause could be that because SRP was being performed in both the groups, it can be hypothesized that benefits could completely be the results of SRP alone without any detectable additive significant effect of LDD.

It is generally believed that one of the reasons that SRP is such an effective therapeutic modality for periodontitis is that the procedure removes subgingival calculus and the subgingival plaque associated with it. In a sense, SRP effectively disrupts (although temporarily) subgingival biofilms that cause periodontitis. In this systematic review, it was found that subgingival insertion of sustained-release antimicrobial systems alone was as effective as SRP alone in producing PD reduction,[8–11] although it has been hypothesized that sub-gingival insertion of the sustained-release system could have both mechanical and chemical (antimicrobial) disruptive effects on the biofilms.[13]

Although all subjects in these four trials were on maintenance at same intervals of time, but then, clearly, based on the available information, it would be premature to conclude that insertion of sustained-release antimicrobial systems are as effective as SRP in all populations of patients. The disease severity might not be same in all the subjects in all four trials at baseline. The reported equivalency of PD reduction achieved with either SRP or sustained-releasing antimicrobial systems might only apply to populations with minimal subgingival calculus.[13] Irrigation systems have little benefit because of rapid clearance of the drug from the site of application and failure of the irrigant to reach all portions of the sub-gingival environment.[28,29]

This systematic review did not report any evidence that use of adjunctive antimicrobial agents causes any major patient-centered undesirable effects compared with SRP alone. Their use apparently does no harm. The lack of significant adverse events is probably due to the non irritating nature of the medications and delivery vehicles employed. In addition, one of the advantages of local drug delivery systems for periodontal therapy is that the total amount of drug used is quite small. Indeed, compared with the systemic administration of antimicrobials, the total body dose of drug delivered with local sustained-release systems is miniscule. Therefore, side-effects associated with relatively high doses of systemically administered antimicrobials are less likely to occur when local drug delivery systems are used.

Thus, evidence presented in this systematic review supports the hypothesis that some sustained-release systems containing certain antimicrobial agents can indeed add to the clinical benefits achieved by SRP. It is highly likely that these systems work by killing or inhibiting the growth of bacteria left behind after SRP.

Adverse events, treatment time, and cost factor are all important in determining whether a given procedure is worth the effort.[30] Determining clinical significance is a highly complex and variable task and involves both the patient's and the therapist's perceptions of benefits gained from the procedure. Findings from the meta-analysis indicate that the average amount of PD reduction achieved by the addition of sustained-release antimicrobials to SRP is statistically significant.

Weakness of the existing literature

Thirty-two studies were selected for a systematic review,[13] among which 28 were RCTs, two were cohort, and two were case–control studies.

Of these 28 RCTs, 13 were in parallel design and only 15 were with in split-mouth design.

The recall intervals for all the studies were not uniform with equal intervals, and varied from 12 to 52 weeks.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria were also not same for all the studies; in few studies, smokers were also included.

Of these 32 studies in the systematic review, 19 were subjected to meta-analysis, in which only 15 were RCTs, with seven split-mouth and eight parallel design. The remaining were case–control and cohort studies.

Furthermore, of these 19 studies, four were equivalence sustained-release studies that compared the outcomes of SRP alone with LDD alone without concurrent SRP.

Strength of the present review

Compared with other systemic reviews in the literature on LDD,[13] the strength of the present meta-analysis lies in the fact that all the studies selected were unicentric, double-blinded RCTs with a split-mouth design-adjunctive sustained-release studies and were performed by same the calibrated examiner thus decreasing the inter-examiner variability. Moreover, all the LDD systems used for the studies were sustained-release preparations. To add to this, all the follow-up intervals and clinical parameters taken into consideration were uniform and same thus further decreasing heterogeneity.

The RCT is considered as the “gold standard” design in clinical research. Moreover, in evidence-based medicine, RCTs are referred to as level 1 evidence, which is the highest level of evidence in the pyramid for clinical significance.

The only limitation of this review is the limited sample size because all the studies were self-funded as compared with other studies[13] that were either sponsored or funded by some industry.

Reviewer's conclusions

Evidence suggests that compared with SRP alone, when SRP is combined with certain anti-infective agents in sustained-release vehicles, statistically significant adjunctive effects on PD reduction and a decreased percentage of sites with BOP can be anticipated. Statistically significant effects of PD reduction were seen with CHX chip.

Compared with SRP alone, no evidence was found for the adjunctive effects on reduction of PI with ATRIDOX and MINO microspheres. BOP reductions were not significant with ATRIDOX and TET fibres.

Meta-analysis has revealed a large effect of adjunctive therapy in pocket depth reduction, with a moderate effect on reduction of bleeding scores and mild effect on reduction of plaque scores.

Use of anti-infective sustained-release systems as adjuncts to SRP does not result in significant patient-centered adverse events or morbidity.

Future focus

Future research is required to assess the effectiveness of sustained-release anti-infective systems in the treatment of all forms of periodontitis. Well-designed RCTs with randomization procedures, therapist and examiner masking, calibration of examiners, type of periodontal disease being treated, definition of study groups and history of past periodontal therapy, consideration of disease severity at baseline and concomitant interventions, or practices that may affect clinical outcomes should be taken into account.

It is strongly recommended that new RCTs in this area include appropriate statistical analyses and that complete data sets be reported to facilitate future evidence-based reviews.

RCTs should be conducted in those populations of patients who would benefit most by being treated with sustained-release anti-infective systems. Most of the studies included in this systematic review probably included large numbers of patients with chronic periodontitis for whom SRP alone was a completely satisfactory treatment. Studies of the effect of sustained-release anti-infective systems on sites that have not responded to conventional SRP, those in which surgical procedures are contraindicated or medically compromised, or in the maintenance phase of therapy would be particularly valuable and will be benefited most.

Future focus is directed to develop novel agents that disrupt existing dental biofilms or interfere with the formation of new ones. Inclusion of biofilm-disruptive agents in sustained-release systems would have considerable promise in the treatment of periodontitis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glossary of Periodontal Terms. 4th ed. Chicago: American Academy of Periodontology; 2001. American Academy of Periodontology; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal diseases: Current concepts. J Periodontol. 1992;63:322–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Schmidt E, Morrison EC. Bacterial profiles of subgingival plaque in periodontics. J Periodontol. 1985;56:447–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.8.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rams TE, Slots J. Local delivery of antimicrobial agents in the periodontal pocket. Periontology 2000. 1996;10:139–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1996.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golub LM, Lee HM, Lehrer G. Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. Preliminary observations and proposed new mechanisms of action. J Periodontol Res. 1983;18:516–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodson JM, Hafajee A, Socransky SS. Periodontal therapy by local delivery of tetracycline. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodson JM, Hogan AE, Dunham SL. Clinical responses following periodontal treatment by local drug delivery. J Periodontol. 1985;56:81–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.11s.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhatar, Shobha prakash, Vandana KL. Comparative evaluation of Atridox (10% Doxycycline hyclate) with SRP in the treatment of periodontitis: A clinical study (Dissertation) Bangalore, India: RGUHS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranthy KR, Kala SB, Prakash S. Clinical and microbiological evaluation of periodontal plus AB in the treatment of periodontitis (Dissertation) Bangalore, India: RGUHS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahendra RC, Chandrashekar KT, Vandana KL. The efficacy of Arestin (minocycline HCL 1 mg) micrispheres in the treatment of chronic adult periodontitis (Dissertation) Bangalore, India: RGUHS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sreenivas R, Shobha prakash, Mehta DS. Comparative evaluation of sustained local drug delivery of chlorhexidine (PerioChip) and phase I therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis (Dissertation) Bangalore, INDIA: RGUHS; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Dental biofilms: Difficult therapeutic targets. Periodontology 2000. 2002;28:12–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanes PJ, Purvis JP. Local anti-infective therapy: Pharmacological agents. A Systematic Review. Ann Periodontal. 2003;8:79–98. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443–90. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caton J, Proye M, Polson AM. Maintenance of healed periodontal pockets after a single episode of root planing. J Periodontol. 1982;53:420–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.7.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaldahl WB, Kalkwarf KL, Patil KD, Dyer JK, Bates RE., Jr Evaluation of four modalities of periodontal therapy: Mean probing depth, probing attachment level and recession changes. J Periodontol. 1988;59:783–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.12.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claffey N, Loos B, Gantes B, Martin M, Heins P, Egelberg J. The relative effects of therapy and periodontal disease on loss of probing attachment after root debridement. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:163–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedrazzoli V, Kilian M, Karring T, Kirkegaard E. Effect of surgical and non-surgical periodontal treatment of periodontal status and subgingival microbiota. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinge B, Attstrom R, Karring T, Kisch J, Lewin B, Stoltze K. 3 regimens of topical metronidazole compared with subgingival scaling on periodontal pathology in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:708–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavia M. Meta-analysis of local tetracycline in treating chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:916–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grac MA, Watts TL, Wilson RF, Palmer RM. A randomized controlled trial of a 2% minocycline gel as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment, using a design with multiple matching criteria. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:249–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paolantonio M, D’Angelo M, Grassi RF, Perinetti G, Piccolomini R, Pizzo G, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of subgingival controlled-release delivery of chlorhexidine chip in the treatment of periodontitis: A multicenter study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:271–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emingil G, Gurkan A, Atilla G, Berdeli A, Cinarcik S. Adjunctive low-dose doxycycline therapy effect on clinical parameters and gingival crevicular fluid tissue plasminogen activator levels in chronic periodontitis. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:437–43. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mızrak T, Guncu GN, Caglayan F, Balci TA, Aktar GN, Ipek F. Effect of a controlled-release chlorhexidine chip on clinical and microbiological parameters and prostaglandin E2 levels in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 2006;77:437–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proye M, Caton J, Polson A. Initial healing of periodontal pockets after a single episode of root planing monitored by controlled probing forces. J Periodontol. 1982;53:296–301. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.5.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisi DC, Salvador SL, Figueiredo LC, Souza SL, Novaes AB, Jr, Grisi MF. Effect of a controlled-release chlorhexidine chip on clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:875–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosyn J, Iris W, Rouck D, Moradi MS. chlorhexidine varnish implemented treatment strategy for chronic periodontitis: Shortterm clinical observations. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:750–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodson JM. Pharmacokinetic principles controlling efficacy of oral therapy. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1625–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quirynen M, Teughels W, DeSoete M, van Steenberghe D. Topical antiseptics and antibiotics in the initial therapy of chronic adult periodontitis: Microbiological aspects. Periodontol 2000. 2002;28:72–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Killoy WJ. The clinical significance of local chemotherapies. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:22–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]