Abstract

Background:

The key to good oral health is hidden in nature. Natural herbs like neem, tulsi, pudina, clove oil, ajwain, triphala and many more has been used since ages either as a whole single herb or as a combination against various oral health problems like bleeding gums, halitosis, mouth ulcers and preventing tooth decay. The aim of the study was to compare the efficacy of a commercially available herbal mouthrinse (Herboral) with that of chlorhexidine gluconate which is considered to be a gold standard as an anti-plaque agent.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized, two-group, parallel study as a ‘de novo’ plaque accumulation model was carried out on 50 subjects (23 males and 27 females). At baseline, all participants received a professional prophylaxis and were randomly assigned to the test (Herbal mouthrinse) and control (Chlorhexidine Gluconate) group. On the following three days, all subjects rinsed with 10 ml of the allocated mouthrinse twice daily for 1 min. They were asked to refrain from use of any other oral hygiene measures during the study. At the end of the experimental period, plaque was assessed and a questionnaire was filled by all subjects.

Results:

Chlorhexidine (mean plaque score=1.65) inhibited plaque growth significantly more than the herbal mouthrinse (mean plaque score=1.43, P<0.001). The results of the questionnaire showed that Herboral was preferred by patients for its taste, its convenience of use and taste duration (aftertaste). However, Chlorhexidine was considered to be more effective in reducing plaque as compared to Herboral.

Conclusion:

Herbal mouthrinse was found to be a potent plaque inhibitor, though less effective than Chlorhexidine Gluconate. However, it can serve as a good alternative for the patients with special needs as in case of diabetics, xerostomics, and so on.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine, herbal, mouthrinse, plaque control

INTRODUCTION

Plaque is known to be the initiating factor in the development of gingivitis when in contact with the gingival tissues and, therefore, plaque control represents the cornerstone of good oral hygiene practice.[1] The tools most commonly used in mechanical supragingival plaque control are the toothbrush (manual or electric), floss, woodsticks, and interdental brushes. Despite the availability of these various oral hygiene devices, even the most meticulous patient will not always completely remove all plaque. Evidence indicates that the degree of motivation and skill required for the effective use of these oral hygiene products may be beyond the ability of the majority of patients.[2] There are also large groups of individuals, such as the handicapped and elderly, for whom maintaining adequate oral hygiene can be an insurmountable problem.[3] For these patients, a chemical plaque control approach is desirable to deal with the potential deficiencies of daily self-performed oral hygiene. Chlorhexidine Gluconate, a bisbiguanide, is considered to date the most effective anti-plaque agent,[4] but it is not a ‘Magic Bullet’ and it also comes with certain side-effects, notably tooth staining, taste disturbance, enhanced supragingival calculus formation and less commonly, desquamation of the oral mucosa.[5–7]

Today's dentists are practicing in an era where the patients are more concerned about both their oral health and their overall medical wellbeing. Thus, in the midst of growing evidence of the connection between oral health and whole body health, herbal medicines with their ‘naturally occurring’ active ingredients offer a gentle and enduring way for restoration of health by the most trustworthy and least harmful way.

Herbal medicine is both promotive and preventive in its approach.[8] It is a comprehensive system, which uses various remedies derived from plants and their extracts to treat disorders and to maintain good health. Natural herbs like triphala, tulsi patra, jyestiamadh, neem, clove oil, pudina, ajwain and many more used either as whole single herb or in combination have been scientifically proven to be safe and effective medicine against various oral health problems like bleeding gums, halitosis, mouth ulcers and preventing tooth decay. The major strength of these natural herbs is that their use has not been reported with any side-effects till date. Apart from this, all herbal mouthrinses do not contain alcohol and/or sugar, two of the most common ingredients found in most other over-the-counter products. The problem of these ingredients is that the microorganisms that cause bad breath and halitosis love to feed on these ingredients, and release byproducts that cause halitosis. Thus, by use of a herbal mouthrinse, we can avoid these ingredients, which itself is one step forward towards better oral hygiene and better health.

In the present study, a commercially available herbal mouthrinse (Herboral), prepared from a combination of ten complex natural herbs was used. The aim of the study was to compare the effectiveness of this herbal mouthrinse with Chlorhexidine Gluconate, which is considered to be the gold standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study population consisted of dental students (undergraduates and postgraduates) of the National Dental College and Hospital, Derabassi. Fifty healthy individuals (27 females and 23 males; age range 18 to 35 years; mean age 23.5 years) were selected for participation in the study. Inclusion criteria included: dentition with ≥20 evaluable teeth (minimum of five teeth per quadrant), no oral lesions, no severe periodontal disease (no probing depth ≥5 mm), no removable prosthesis or orthodontic bands or appliances worn at the time of study. Persons with any past history of systemic illness or allergy to components of mouthrinse were excluded from the study.

All subjects were explained the purpose of the study and were asked to sign an informed consent. The study was conducted from 5 April to 22 May 2010 in the Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology, National Dental College and Hospital, Derabassi. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee and was carried out in accordance with the principles originating in the Declaration of Helsinki, and consistent with good clinical practices.

Study design

The study was a randomized, two-group, parallel experiment as a ‘de novo’ plaque accumulation model. At baseline, plaque was disclosed with a disclosing solution (containing 2% erythrosine), and all participants received a thorough supragingival scaling and root planing to remove all plaque, stains and calculus. This was performed using hand instruments, mechanical scalers, and rotating brushes and polishing paste. To ensure that all deposits had been removed, a second disclosing session was carried out to remove any remaining plaque. Subjects were randomly assigned to Group A (test) or Group B (control).

During this three-day experimental non-brushing period, subjects in the test group used herbal mouthrinse (Herboral), whereas those in the control group used 0.2% Chlorhexidine (CHX) Gluconate mouthrinse.

All participants were instructed to refrain from using any other means of oral hygiene during the experimental period. Written instructions regarding the use of mouthrinse were provided to every participant. They were instructed to rinse twice daily with 10 ml of the allocated mouthrinse (undiluted) for 60 sec, after which they could spit. Subsequent rinsing with water was not allowed. Rinsing was performed at home without supervision. To check for compliance, subjects were asked to note the times of the day when they rinsed.

After three days, when subjects reported to the clinic for plaque assessments, the dentition was disclosed with the disclosing solution. Subsequently, the level of plaque was assessed at six sites per tooth using the Quigley and Hein index[9] modified by Turesky et al.[10] and further modified by Lobene et al.[11] All measurements were carried out under the same conditions by the same investigator who was unaware of the allocation of the mouthrinse to the participants. Finally, after plaque scoring, all subjects received a questionnaire designed to evaluate their attitudes with regard to the product used using a visual analog scale (VAS). Subjects marked a point on a 10-cm-long uncalibrated line with the negative extreme response (0) at the left end and the positive extreme response (10) at the right end.

Statistical analysis

The plaque score was used as the main response variable. Mean plaque scores were calculated at the subject level. A non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney test) was used to compare the differences between the two groups. P value <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

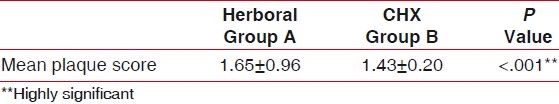

All subjects (N=50) completed the three-day experimental period. The mean plaque scores for the test and control groups at the end of the experimental period are summarized in Table 1. There was a significant difference in plaque levels between the two groups. In the test group, the mean overall mouth plaque index score was 1.65±0.96, compared to 1.43±0.20 in the control group. The difference of 0.23±0.76 between the two groups was statistically significant (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of mean plaque scores for Group A and B

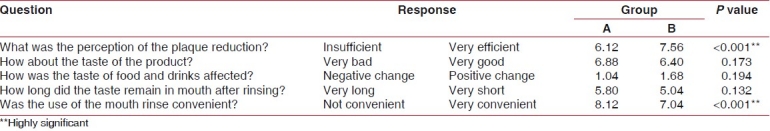

The results of the questionnaire are shown in Table 2. With regard to taste of the product, duration of taste and alteration of taste perception, the differences between the two groups were statistically non-significant. With respect to perception of plaque reduction and convenience, the differences between the two groups were statistically significant (P<0.001). More specifically, subjects preferred the taste of Herboral mouthrinse (VAS 6.88) over the taste of CHX (VAS 6.40, P=0.173). They also experienced that taste duration (aftertaste) in their mouth after rinsing with Herboral (VAS 5.80) was much less than after rinsing with CHX (VAS 5.04, P=0.132). Also, subjects found Herboral more convenient to use (VAS 8.12) as compared to CHX (VAS 7.04, P<0.001). However, they considered CHX (VAS 7.56) to be more effective in reducing plaque in the mouth compared to Herbal mouthrinse (VAS 6.12, P<0.001). Also, with respect to alterations in taste perception, CHX (VAS 1.68) was preferred over Herboral (VAS 1.04, P=0.194).

Table 2.

Questionnaire to evaluate their attitude with regard to Group A and B

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to determine the efficacy of a herbal mouthrinse (Herboral) with 0.2% Chlorhexidine Gluconate. In this study, we used a three-day non-brushing model that allowed for plaque accumulation. This design was previously used to assess the effect of various mouthrinses (Dona et al.,[12] Keijser et al.,[13] van der Weijden et al.,[14] Paraskevas et al.,[15]). It was a convenient model to assess the plaque-inhibitory capacity of the test product per se and to determine its relative activity in relation to the well established action of CHX. Using such a three-day plaque accumulation model provides a general indication of how the product in question would perform under actual conditions, insofar as significant plaque reduction is a prerequisite for the reduction in gingivitis.[16]

Herboral is a herbal preparation, made from ten natural herbs i.e. triphala (Three myrobalans), khadir chaal (Acacia catechu), bakul chaal (Mimusops elengi), tulsi patra (Ocimum sanctum), jyestiamadh (Glycyrrhiza glabra), maypal (Quercus infectonia), neem paan (Azadirachta indica), clove oil (Caryophyllus aromaticus), pudina ke phool (Metha spicate) and ajwain ke phool (Apium gravcolens). Because of its unique combination of herbs Herboral possesses various beneficial properties like antiseptic (due to the presence of tulsi, neem), antibiotic (due to the presence of khadir chaal), analgesic (by virtue of tulsi, ajwain, clove oil), astringent (by virtue of bakul chaal, khadir chaal), and anti-inflammatory and immunity booster (due to the presence of triphala). Also, maypal present in Herboral can be used to cure gum diseases and whiten teeth, and jyestiamadh at the same time can be used against mouth ulcers. Apart from these, Herboral is a non-alcoholic preparation, with no added sugar, no artificial preservatives, no artificial flavors and colors and absolutely no side-effects.

Kaim et al.,[17] in a study, investigated the anti-microbial activity of herbal mouthrinse with Listerine and 0.12% Chlorhexidine Gluconate (Peridex) against S. mutans, S. sanguis and A. viscosus. It was found that herbal mouthrinse produced the largest zones of microbial inhibition when compared to Listerine against all the three bacteria tested. However, when compared to Peridex, herbal mouthrinse produced larger zones of microbial inhibition against two of three bacteria tested, and a similar zone of inhibition against the third bacteria tested.

Similarly, Haffajee et al.,[18] compared the effectiveness of herbal mouthrinse (The Natural Dentist, Medford, Mass) with 0.12% Chlorhexidine Gluconate and an essential oil mouth rinse. It was found that herbal mouthrinse (though less potent than CHX) was effective in inhibiting oral bacteria, predominantly Actinomyces sp., E. nodatum, P. intermedia, P. melaninogenica, P. nigrescens and T. forsythia. Herbal mouthrinse was found to be a more effective antimicrobial agent than essential oil mouth rinse.

In the present study, Herboral has shown a good potential as an anti-plaque agent. But in comparison to Chlorhexidine Gluconate, it has proven to be less effective. In the Questionnaire, with regard to the subjects’ rating about the plaque reduction efficacy and convenience of use, significant differences between the two groups were found. Subjects preferred Herboral for its taste, convenience of use and taste duration (aftertaste) in their mouth after rinsing, which may be attributed to the presence of natural herbs like tulsi, pudina etc. present as active ingredients.

In regard to the efficacy of plaque reduction, CHX was considered to be more effective. However, CHX rinsing can cause a number of local side-effects including extrinsic tooth and tongue brown staining, taste disturbance, enhanced supragingival calculus formation and, less commonly, desquamation of the oral mucosa. These side-effects limit its acceptability to users and the long-term use of CHX-containing mouthrinses. On the other hand, Herboral due to its natural ingredients does not cause any side-effects and can serve as a good alternative to patients who wish to avoid alcohol (e.g. Xerostomics), sugar (e.g. Diabetics), any artificial preservatives and artificial colors in their mouthrinses. Further, more research is necessary to gain greater insight into the level of plaque inhibition achieved with this herbal mouthrinse. Studies of longer duration, in which the product in question is compared to other control (positive or negative) or placebo products and where safety and microbiological parameters will be assessed, are necessary to establish the effectiveness of this product and its place among the other agents used for chemical support of daily mechanical plaque removal.

CONCLUSION

Herboral mouthrinse was found to be a potent plaque inhibitor, though less effective than Chlorhexidine Gluconate. However, it was preferred by the patients for its taste, convenience of use and taste duration (aftertaste) in their mouth after rinsing. Moreover, it can serve as a good alternative for patients with special needs as in case of Diabetics, Xerostomics, etc.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindhe J, Koch G. The effect of supervised oral hygiene on the gingiva of children. Lack of prolonged effect of supervision. J Periodont Res. 1967;2:215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1967.tb01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalaga A, Addy M, Hunter B. The use of 0.2% chlorhexidine as an adjunct to oral health in physically and mentally handicapped adults. J Periodontol. 1989;60:381–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.7.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CG. Chlorhexidine: Is it still the gold standard? Periodontol 2000. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addy M, Moran J. Chemical supragingival plaque control. In: Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP, editors. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 5th ed. Copenhagen: Blackwell Mumksgaard; 2008. pp. 734–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos A. Evidence based control of plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(Suppl 5):13–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.30.s5.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pizzo G, Cara ML, Licata ME, Pizzo I, Angelo MD. The effects of an essential oil and an amine fluoride/stannous fluoride mouthrinse on supragingival plaque regrowth. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1177–83. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amruthesh S. Dentistry and Ayurveda – III (basics – ama, immunity, ojas, rasas, etiopathogenesis and prevention) Indian J Dent Res. 2007;18:112–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.33786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quigley GA, Hein JW. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:26–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of vitamin C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lobene RR, Soparkar PM, Newman MB. Use of dental floss. Effect on plaque and gingivitis. Clin Prev Dent. 1982;4:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dona BL, Grundemann LJ, Steinfort J, Timmerman MF, van der Weijden GA. The inhibitory effect of combining chlorhexidine and hydrogen peroxide on 3-day plaque accumulation. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:879–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keijser JA, Verkade H, Timmerman MF, van der Weijden GA. Comparison of 2 commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Weijden GA, Timmerman MF, Novotny AG, Rosema NA, Verkerk AA. Three different rinsing times and inhibition of plaque accumulation with chlorhexidine. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:89–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paraskevas S, Rosema NA, Versteeg P, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Chlorine dioxide and chlorhexidine mouthrinses compared in a 3-day plaque accumulation model. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1395–400. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riep BG, Bernimoulin JP, Barnett ML. Comparative antiplaque effectiveness of an oil and an amine fluoride/stannous fluoride mouthrinse. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:164–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaim JM, Gultz J, Do L, Scherer W. An in vitro investigation of the antimicrobial activity of an herbal mouthrinse. J Clin Dent. 1998;9:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haffajee AD, Yaskell T, Socransky SS. Antimicrobial effectiveness of an herbal mouthrinse compared with an essential oil and a chlorhexidine mouthrinse. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:606–11. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]