Abstract

Context:

Survey.

Aims:

The objective of the study was to evaluate the periodontal health status among cigarette smokers and non cigarette smokers, and oral hygiene measures.

Settings and Design:

Cross sectional study.

Materials and Methods:

The study included 400 male (200 cigarette smokers and 200 non smokers) aged 18-65 years. The subjects were randomly selected from the patients attending dental out-patient department of civil hospital and Himachal Dental College, Sundernagar. Community Periodontal Index (CPI) score was recorded for each patient and a questionnaire was completed by each patient.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi square and t-test.

Results:

Periodontal condition as assessed by CPI score showed that there was statistically significant difference in the findings between cigarette smokers and non-smokers.

Conclusions:

Within the limits of this study, positive association was observed between periodontal disease and cigarette smoking. It was found that cigarette smoking was associated with lesser gingival bleeding and deeper pockets as compared to non-smokers.

Keywords: Community periodontal index, periodontal disease, smoking

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is one of the most common chronic diseases in adults.[1] It is second only to dental caries as a cause of tooth loss among adults in developed countries.[2]

About 80% of myocardial infarctions before the age of 50 years, and 70% of chronic lung diseases are caused by tobacco smoking.[3]

Tobacco smoking, mostly in the form of cigarette smoking, is recognized as the most important environmental risk factor in periodontitis.[4]

Periodontal diseases are a dynamic phenomenon with cyclical patterns of progression and resolution at any given site.[5] Smoking is thought to impair the immune response and compromises the periodontal tissue's ability to heal, following a period of disease activity.[6]

It has been well demonstrated that there is a close-response relationship for tobacco use and the risk of the development of oral cancer.[7]

The population impact of smoking on periodontitis also varies according to the frequency of exposure to tobacco smoking in populations.[8] Gingival bleeding has been consistently reported to occur less in smokers due to nicotine induced vasoconstriction in smoker's gingiva as well as heavy gingival keratinization.[9] Pocket depth measurements are found to be greater in smokers due to increased alveolar bone loss.[10,11]

Tobacco smoking probably plays a significant role in the development of refractory periodontitis.[12] Periodontal breakdown has been shown to be more severe among current smokers compared to former smokers. Those who have never smoked have been observed to have the lowest risk.[13] Smoking has a strong negative impact on regenerative therapy, including osseous grafting, guided tissue regeneration, or a combination of this treatment.[14]

Josef[15] examined periodontal needs according to the community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) and smoking habits. The results showed that effect of both smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked had deleterious effect on periodontal status. Gerad et al.,[16] concluded that cigarette smoking was a major environmental factor associated with accelerated periodontal destruction in young adults. Palmer et al.,[17] reviewed the potential biological mechanisms underlying the effects of tobacco smoking on periodontitis and concluded that tobacco smoking has widespread systemic effects, many of which may provide mechanisms for the increased susceptibility to periodontitis and the poorer response to treatment. Torrungruang,[18] determined the effect of cigarette smoking on the severity of periodontitis in a cross-sectional study of older Thai adults and concluded that there was a strong association between cigarette smoking and the risk of periodontitis.

Ankola et al.,[19] conducted a comparative study of periodontal status and loss of teeth among smokers and non smokers of Belgaum city and concluded that smoking was associated with higher plaque and calculus deposits. Vered et al.,[20] evaluated the periodontal status and present smoking habits among a representative sample of young adult Israelis, and investigated possible associations and concluded that only 7% of the participants demonstrated signs of periodontitis and most young adults did not smoke.

During periodontitis, cigarette smoking may differentially affect neutrophil function, generally preventing elimination of periodontal pathogens, but, in heavy smokers also stimulated reactive oxygen species release and oxidative stress mediated tissue damage.[21] Tymkiw et al.,[22] compared the expression of 22 chemokines and cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid from smokers and non-smokers, with periodontitis and periodontally healthy control subjects, and concluded that periodontitis subjects had significantly elevated cytokine and chemokine profiles. Smokers exhibited a decrease in several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and certain regulators of T-cells and natural killer cells. This reflected that the immunosuppressant effects of smoking which may contribute to an enhanced susceptibility to periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sample

A cross sectional study design was used. This study included 400 male aged 18 to 65 years attending dental out-patient department of civil hospital and Himachal Dental College, Sundernagar. Community Periodontal Index (CPI) was used as an epidemiological tool. Patients were randomly selected depending on following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Over 18 years of age and not older than 65 years of age.

More than 10 natural teeth present.

Exclusion criteria

Chronic systemic pathology, such as diabetes, other endocrine pathologies, hematological pathologies.

Periodontal health, with no clinical signs of periodontal inflammation (CPI=0).

Subjects were divided into two groups:

Cigarette smokers

Non-smokers

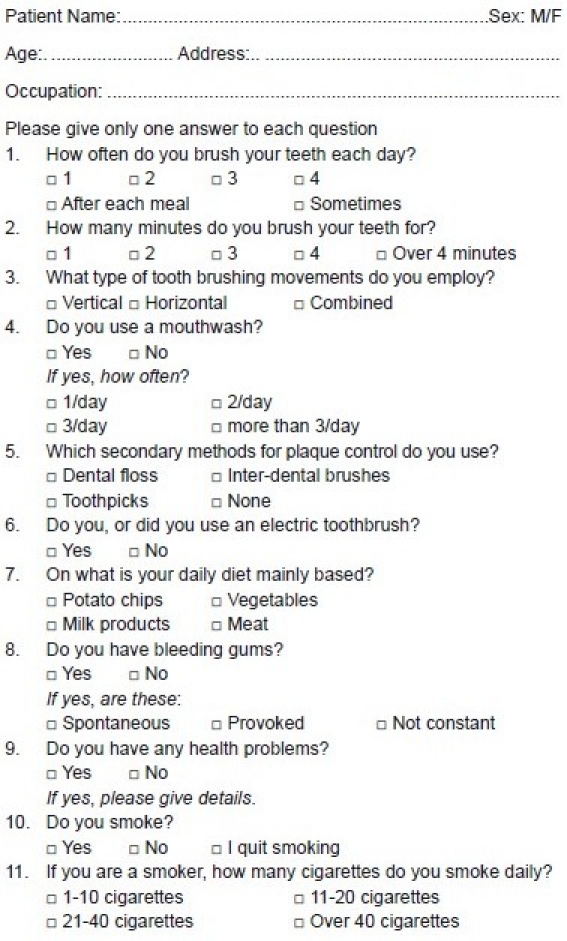

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed. It included questions on oral hygiene habits and smoking habits.

Questionnaire

Clinical examination

The periodontal examination was conducted using the mouth mirror and CPITN probe, and the CPI score was recorded.

Codes and criteria of CPI index

Code-0=No periodontal disease (healthy periodontium).

Code-1=Bleeding observed during or after probing.

Code-2=Calculus or other plaque retentive factors either seen or felt during probing.

Code-3=Pathological pocket 4 to 5 mm in depth. Gingival margin situated on black band of the probe.

Code-4=Pathological pocket 6 mm or more in depth. Black band of the probe is not visible.

Ethics

The ethical committee of the Himachal Dental College approved the study. Patients who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. At the conclusion of the study, the participants were provided with oral health instructions and a specific periodontal treatment plan.

RESULTS

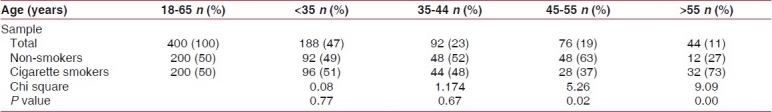

Young adults under 35 years represented the majority of the study population, that is 47% of the total sample, 51% were current cigarette smokers. In the oldest age group (over 55 years), only a small proportion (11%) were current cigarette smokers [Table 1].

Table 1.

Study group according to age and cigarette smoking

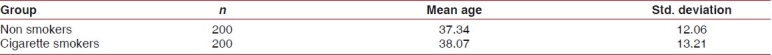

The mean age of 37.34 years (SD 12.06) was in the non smoker group, and mean age of 38.07 years (SD 13.21) was in the cigarette smoker group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation according to age among cigarette smoker and non smoker group

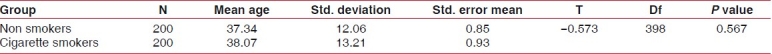

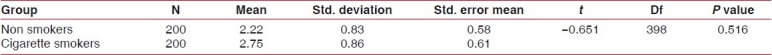

The difference in age in cigarette smokers and non smokers was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison t-test on age between cigarette smokers and non smokers

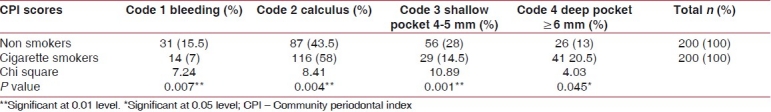

Periodontal condition as measured by maximum CPI score per person showed that in the group studied, there were statistically significant differences between cigarette smokers and non smokers for CPI score of 1 (P=0.007; non smokers more likely to have gingival bleeding), 2 (P=0.004; cigarette smokers more likely to have calculus present), CPI score 3 (P=0.001; non smokers more likely to have shallow pockets), and CPI score 4 (P=0.045; cigarette smokers more likely to have deep pockets) [Table 4].

Table 4.

CPI scores according to reported cigarette smoking

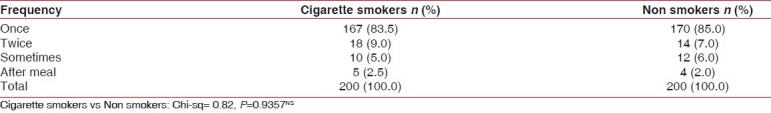

According to the self-reported oral hygiene practices, the mean tooth brushing frequency in cigarette smokers was slightly higher compared with the non smoker group, but was not found to be statistically significant [Table 5]. Cigarette smokers also reported that they brushed their teeth for longer than non smokers. The tooth brushing time per minute was not statistically significant in non smoker, and the cigarette smoker group at 0.05 level of significance [Table 6].

Table 5.

Tooth brushing frequency/times per day among cigarette smokers and non smokers

Table 6.

Tooth brushing times/minutes per day

DISCUSSION

It has been estimated that about a third of the male adult global population smokes. Among the young, one in five smokes worldwide. Between 80,000 and 100,000 children worldwide, starts smoking every day.[19] In the current study, 51% of all smokers were young adults under 35 years of age.

Smoking is on the rise in the developing world, but falling in developed nations. About 15 billion cigarettes are sold daily or 10 million every minute.[23] Smoking has clearly been implicated contributing to periodontal breakdown and in impeding healing of periodontal tissues.[24]

Tobacco smoke contains many cytotoxic substances such as nicotine, which can penetrate the soft tissue of oral cavity, adhere to the tooth surface or enter to the blood stream. Potential molecular and cellular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of smoking associated periodontal diseases has been reported and these include, immuno-suppression, exaggerated inflammatory cell responses, and impaired stromal cell functions of oral tissues. The association between cigarette smoking and periodontal diseases represent a significant oral health problem.[25]

The findings in the present study are consistent with the study of Feldman et al.,[26] showed that smokers with periodontal disease had less clinical inflammation and gingival bleeding when compared with non smokers. This may be explained by the fact that one of numerous tobacco smoke by-products, nicotine, exerts local vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow, edema and acts to inhibit what are normally early signs of periodontal problems by decreasing gingival inflammation, redness, and bleeding.

Some in vitro studies provided other possible intimate mechanisms by which smoking may affect bone metabolism. Rosa et al.,[27] reported that nicotine increased the secretion of interlukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in osteoblasts and production of tissue-type plasminogen activator, prostaglandin E2, and matrix metalloproteinase, thereby tipping the balance between bone matrix formation and resorption toward the latter process, as reported by Katano et al.[28] Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa ß ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) are members of the tumor necrosis factor super family. RANKL promotes osteoclastic differentiation and activates bone resorption. In contrast, OPG inhibits osteoclasto-genesis and suppresses bone resorption by inhibition of RANKL. Another potential mechanism of bone loss in smokers may be the suppression of OPG production and a change in the RANKL/OPG ratio. Although bacteria are the primary etiologic factors in periodontal disease, the patient's host response is a determinant of disease susceptibility.

Smokers appear to have depressed numbers of helper lymphocytes, which are important to B-cell function and antibody production.[25]

The combined effect of bacterial colonization and the local and systemic effect of smoking are responsible for the greater severity of periodontal destruction in smokers of the current study. These results of the current study are similar to those reported by Linden and Mullally,[29] Harber et al.,[30] Schenkein et al.,[31] and Haffajee.[32] All of these studies have shown that compared to non-smokers, young adult smokers have a higher prevalence and severity of periodontitis. At the same time, results of the present study showed that the gingival bleeding and gingival inflammatory symptoms appeared to be suppressed in smokers. These results are parallel to those reported by Schuller,[33] Bergström and Boström[34] and Chen et al.[35]

In this study, we used the CPI as recommended by the World Health Organization. CPI is not a perfect measure of periodontal disease and excludes measurement of attachment loss, gingival recession, alveolar bone level, and other clinical periodontal parameters. Nevertheless, it was originally proposed as an appropriate estimation of disease in large epidemiological surveys and has contributed to an understanding of the epidemiology of periodontal disease on a global level.[36]

Data from the present study may therefore only offer an estimation of the prevalence of the moderate or deep periodontal pocketing, and not of all clinical disease parameters. The result of this study confirms a consistent association between smoking and periodontal status. However, smoking duration was not recorded and this determinant could not be included in the analyses. It should be noted that given the small difference between smokers and non smokers, other factors should have been considered such as socio-economic status and stress.

In conclusion, the current study shows that smoking is a major environmental factor associated with accelerated periodontal destruction. The progression and excessive loss of periodontal support in later life depends to a greater extent upon excessive smoking in youth. The findings highlight the need for preventive strategies aimed at young individuals, many of whom take up smoking as a habit, early in life. Dental public health efforts, therefore, need to include and emphasize the role of smoking and not only oral hygiene in primary preventive efforts.

Statistics/data analysis

The association of cigarette smoking and other risk factors for periodontal status was examined in this comparative, cross sectional study. The Chi-square test was used to test whether the variables had normal or non-normal distribution. The t-test was used to compare group means.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lung ZH, Kelleher MG, Porter RW, Gonzalez J, Lung RF. Poor patient awareness of the relationship between smoking and periodontal diseases. Br Dent J. 2005;199:731–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdulkarim AA, Mokuolu OA, Adeniyi A. Drug use among adolescents in Ilorin, Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2005;35:225–8. doi: 10.1258/004947505774938620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson NW, Bain CA. Tobacco and Oral disease. Br Dent J. 2000;189:200–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer RM, Wilson RF, Hasan AS. Mechanism of action of environmental factors- tobacco smoking. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:180–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locker D, Leake JL. Risk factors and risk markers for periodontal disease experience in older adults living independently in Ontario, Canada. J Dent Res. 1993;72:9–17. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720011501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson GK, Hill M. Cigarette smoking and the periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:196–209. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynder EL, Mushinski MH, Spivah JC. Tobacco and alcohol consumption in relation to development of multiple primary cancers. Cancer. 1977;40:1872–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4+<1872::aid-cncr2820400817>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loc G, Gary S. Smoking attributable periodontal disease in the Australian adult population. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijerya’li E. Oral hygiene status and periodontal treatment needs of Nigerian Male smokers. TAF Prev Med Bull. 2010;9:107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoltenberg J, Osborn JB, Pihlstrom BL, Herzberg MC, Aeppli DM, Wolff LF, et al. Association between cigarette smoking, bacterial pathogens and periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1993;64:242–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstrom J. Cigarette smoking and periodontal bone loss. J Periodontol. 1991;62:242–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.4.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Academy Reports. Tobacco use and the periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1419–27. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.11.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel C, Totolic I, Girdia M, Dumitriu SA, Hanganu C. Tobacco smoking and periodontal conditions in an adult population from Constanta, Romania. OHDMBSC. 2009;8:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson G. Impact of tobacco use on periodontal status. Impact of tobacco use on periodontal status. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:313–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josef G. Association of smoking with periodontal treatment needs. J Periodontol. 1990;6:364–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.6.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerard J, Brian H. Cigarette smoking and periodontal destruction in young adults. J Periodontol. 1994;7:718–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer RM, Wilson RF, Hasan AS, Scott DA. Mechanism of action of environmental factors-tobacco smoking. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:180–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrungruang K. The effect of cigarette smoking on the severity of periodontal disease among older Thai adults. J Periodontol. 2005;4:566–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ankola A, Nagesh L, Tangade P, Hegde P. Assessment of Periodontal status and loss of teeth among smokers and non-smokers in Belgaum city. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:75–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vered Y, Livny A, Zini A, Sgan-Cohen HD. Periodontal health status and smoking among young adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:768–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews JB, Chen FM, Milward MR, Wright HJ, Carter K, McDonagh A, et al. Effect of nicotine, cotinine and cigarette smoke extract on the neutrophil respiratory burst. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:208–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tymkiw KD, Thunhell DH, Johnson GK, Joly S, Burnell KK, Cavanaugh JE, et al. Influence of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokines in severe chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:219–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World health organization Western Pacific Region, Fact sheets. 2002 May 28; [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson NW, Bain CA. Tobacco and oral disease. EU-Working Group on tobacco and oral health. Br Dent J. 2000;189:200–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dina Al-Tayeb. The effects of smoking on the periodontal condition of young adult saudi population. Egypt Dent J. 2008;54:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman RS, Bravacos JS, Rose CL. Associations between smoking, different tobacco products and periodontal disease indexes. J Periodontol. 1983;54:481–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1983.54.8.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosa MR, Luca GQ, Lucas ON. Cigarette smoking and alveolar bone in young adults: A study using digitized radiographic. J Periodontal. 2008;79:232–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.060522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katono T, Kawato T, Tanabe N. Nicotine treatment induces expression of matrix metalloproteinases in human osteoblastic Saos-2 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2006;38:874–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2006.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linden GJ, Mullally BH. Cigarette smoking and periodontal destruction in young adults. J Periodontol. 1994;65:718–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haber Cigarette smoking: A major risk factor for periodontitis. Compend Continuing Educ Dent. 1994;15:1002–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schenkein HA, Gunsolley JC, Koertge TE, Schenkein JG, Tew JG. Smoking and its effects on earlyonset periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1107–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Relationship of cigarette smoking to attachment level profiles. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:283–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028004283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuler RL. Effect of cigarette smoking on the circulation of the oral mucosa. J Dent Res. 1968;47:910–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345680470065201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergström J, Boström L. Tobacco smoking and periodontal hemorrhagic responsiveness. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:680–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028007680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Wolff L, Aeppli D, Guo Z, Luan W, Baelum V, et al. Cigarette smoking, salivary/gingival crevicular fluid cotinine and periodontal status. A 10-yer old longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:331–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028004331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cutress TW, Ainamo J, Sardo J. The community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) procedure for population groups and individuals. Int Dent J. 1987;37:222–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]