Abstract

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis is a rare disorder characterized by various degrees of attached gingival overgrowth. Gingival fibromatosis usually develops as an isolated disorder but can be one feature of a syndrome. A case of a 17-year-old female who presented with a generalized severe gingival overgrowth, involving the maxillary and mandibular arches and covering almost the whole dentition. Excess gingival tissue was removed by conventional gingivectomy under local anesthesia. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient's appearance improved considerably. Good esthetic result was achieved without recurrence of the gingival overgrowth. After treatment, regular recall visits are necessary in order to evaluate oral hygiene, and the stability of the periodontal treatment.

Keywords: Gingival fibromatosis, gingivectomy, hereditary gingival fibromatosis

INTRODUCTION

Gingival fibromatosis is a slowly progressive gingival enlargement caused by collagenous overgrowth of the fibrous component of the gingival connective tissue. Gingival fibromatosis may be familial or idiopathic. The familial variations may occur as an isolated finding or in association with one of several hereditary syndromes, for example, Zimmermann–Laband,[1] Murray–Puretic–Drescher,[2] Rutherfurd, multiple hamartoma, and Cowden syndrome.[2] Findings seen sometimes in conjugation with gingival fibromatosis include hypertrichosis,[3] epilepsy, and mental retardation.[4] Hearing loss and supernumerary teeth have also been associated with hereditary gingival fibromatosis.[5] This condition has also been reported in association with deficiency of growth hormone caused by lack of growth hormone release factor.[6]

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis, also known as elephantiasis gingiva, hereditary gingival hyperplasia, idiopathic fibromatosis, and hypertrophied gingiva, is a rare hereditary condition characterized by slow, progressive enlargement of the gingiva.[7] Most cases of hereditary gingival fibromatosis appear to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner, although autosomal recessive inheritance has also been reported. Autosomal-dominant forms of gingival fibromatosis, which are usually nonsyndromic, have been genetically linked to the chromosome 2p21-p22 and 5q13-q22.[8] In modern times, a mutation in the son of sevenless-1 (SOS-1) gene has been suggested as a possible cause of isolated (nonsyndromic) gingival fibromatosis. However, no definite linkage has been established.[9] Recent research has shown that 2 genetically separate loci are responsible for the autosomal dominant type of fibromatosis.[10]

The hyperplastic gingiva usually presents a normal color and has a firm consistency with abundant stippling. Buccal and lingual tissues may be involved in both the mandible and the maxilla. This anomaly is classified into 2 types according to its form—the nodular form and the symmetric form. The localized nodular form is characterized by the presence of multiple enlargements in the gingiva. The symmetric form, which is the most common type of the disorder, results in uniform enlargement of the gingiva. The degree of enlargement may vary from mild to severe and may be the same between individuals within the same family.[11] The gingival enlargement is rarely present at birth. It usually begins at the time of eruption of the permanent dentition but can develop with the eruption of the primary dentition.[12] The most common effects related to gingival overgrowth are diastemas, malpositioning of teeth and prolonged retention of primary teeth. More severe lesions may cover the dental crowns, resulting in both esthetic and functional problems. Although gingival overgrowth occurs, the alveolar bone is usually not affected.[11]

Histologically, hereditary gingival fibromatosis consists of dense or moderately dense, avascular, bland of collagenic connective tissue with scattered chronic inflammatory cells, beneath the surface epithelium. The attached gingival epithelium may have extremely elongated rete processes.

This report presents the clinical features and the management of a 17-year-old female patient with hereditary gingival fibromatosis who was followed-up for 2 years.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female reported to the Department of Periodontics, People's College of Dental Science and Research Centre, complaining of gingival swelling, which hampered speech, mastication, and esthetics. The patient reported that the gingival enlargement had started at the time of eruption of permanent dentition with slow progression; due to which there was a delayed eruption of permanent dentition. The enlargement had influenced the position of her teeth, in such as way that the dentition appeared with diastema and malpositioning.

Extraoral examination revealed a convex profile with incompetent lips and malocclusion. Intraoral examination revealed generalized gingival overgrowth involving both the mandibular and maxillary arches. The tissue covered more than half of the crown surfaces. The gingiva was pink, with a firm and dense consistency. There was generalized spacing in the dentition with proclined maxillary anteriors [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph showing severe gingival hyperplasia

Panoramic radiograph was taken, which revealed normal bone height. Routine blood investigations showed values within normal range.

The patient's medical history was not indicative of drug-induced gingival enlargement or hormonal changes and exhibited no signs of hypertrihcosis or mental retardation that could be associated with gingival hyperplasia.

Her family history was of significance since, according to the patient, her brother (21 years old) and her sister (15 years old) had gingival enlargement but according to the patient there was no esthetic problem. However, these cases did not report to the hospital for treatment.

The treatment consisted of external bevel gingivectomy performed under local anesthesia quadrant wise. Postoperative periodontal dressing was applied. A 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse was prescribed twice a day for 2 weeks.

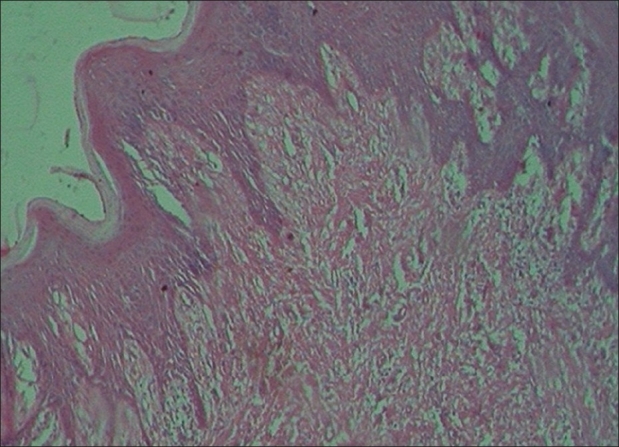

A biopsy sample of the gingival tissues was submitted for histologic evaluation. The sections revealed moderately dense collagenous connective tissue with collagen bundles arranged in a haphazard manner. Connective tissue was relatively avascular along with scanty inflammatory cell infiltrate. The overlying epithelium was hyperplastic with elongated rete ridges. The histopathologic features were suggestive of gingival fibromatosis [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph depicting hyperplastic parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with dense collagenous connective tissue. (H and E, ×200)

Post-surgical healing was uneventful. The dressing was removed after 1 week. The patient was recalled at 1, 3, and 6 months post surgery and after that she was recalled at 6 months interval for up to 24 months after surgery. During this period, no recurrence was seen [Figure 3]. Three months after surgery, the patient was suggested to undergo orthodontic treatment for diastema and malpositioning correction. However, the patient did not undergo orthodontic treatment.

Figure 3.

Two years post-treatment with no signs of recurrence of the gingival hyperplasia

DISCUSSION

This article reports a case of Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis may be congenital or hereditary. Although the genetic mechanism is not well understood, majority of authors have attributed the condition related with hereditary factors.[13] In this case, the patient did not exhibit any signs or symptoms suggesting that the condition was syndromic. The diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical presentation, family history, and characteristic microscopic features of the histologic samples.

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis can be inherited as an autosomal-dominant or recessive condition. Bozzo and colleagues in 1994 reported autosomal dominance in a four-generation pedigree with 50 of 105 at-risk family members developing gingival fibromatosis.[14] In the present case, the gingival enlargement was a hereditary condition, probably autosomal dominant, due to its existence in siblings (father, brother, and sister), although there were other close relatives (other sister and mother) who were phenotypically normal. On the other hand, it was not related to endocrine problems or use of drugs.

There is inconsistency in the literature as to the cellular and molecular mechanisms that lead to gingival fibromatosis. Some authors report an increase in the proliferation of gingival fibroblasts,[15] whereas others report slower-than normal growth.[16] Increased collagen synthesis rather than decreased levels of collagenase activity may be involved.[15]

The gingival enlargement usually begins at the time of eruption of the permanent dentition[12] or less frequently, with the eruption of the primary dentition.[11] In this case, the patient reported that gingival enlargement had started at the time of eruption of permanent dentition with slow progression; due to which there was a delayed eruption of permanent dentition. The enlargement had influenced the alignment of her teeth resulting in diastema and malpositioning. It has been suggested that gingival enlargement may be due to nutritional and hormonal factors, but these have not been completely substantiated. The constant increase in the tissue mass can result in delayed eruption and displacement of teeth, arch deformity, spacing, and migration of teeth.[12] The condition is not painful until the tissue enlarges to partially cover the occlusal surface of the molars, and thereby getting traumatized during mastication. In the present case, enlargement was not found to cover the occlusal surface, although due to massive gingival enlargement, the patient experienced difficulty in speech and maintaining oral hygiene measures. This could have resulted in the accumulation of materia alba and plaque, which could have further complicated the existing situation.

The microscopic features of the present case were classic of gingival fibromatosis, that is, hyperplastic epithelium with elongated rete ridges and dense fibrous connective tissue stroma underneath.[17]

The suggested treatments vary according to the degree of severity. When the enlargement is minimal, good scaling of teeth and home care may be sufficient to maintain good oral health. As the excess tissue increases, appearance and functional impairment dictate the need for surgical intervention.[12] Treatment consists of surgical excision of the hyperplastic tissue to restore the gingival contours. With the exception of carbon dioxide laser, which has been used in some studies,[18,19] the most widely used method of removing large quantities of gingival tissue is the conventional external bevel gingivectomy with gingivoplasty, particularly when there are pseudopockets with no attachment loss.[11,17,20] A periodontal flap procedure may be preferred for the treatment of gingival enlargement if there are large areas of gingival overgrowth or attachment loss and osseous defects.[21] Whenever possible, the treatment should be performed after complete eruption of the permanent dentition. Recurrence is a common feature over varying periods. One report indicated that there is less chance of recurrence if the gingivectomy is delayed until the permanent dentition is in place.[22] However, slight recurrence was seen after 20 months.[17] In several reported cases there was no recurrence in a period of 2 years,[12] 3 years[11] or even a 14-year follow-up.[23]

For the present case, gingivectomy under local anesthesia was the favored treatment and there was no recurrence of the gingival enlargement during 2 years follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis is a rare disorder characterized by various degrees of attached gingival overgrowth. Unesthetic appearance and impaired function often demand surgical intervention, although recurrence cannot be predicted. Good esthetic result was achieved without recurrence of the gingival overgrowth. After treatment, regular recalls are necessary in order to evaluate oral hygiene, and the stability of the periodontal treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Backen G, Scully C. Hereditary Gingival fibromatosis in a family of Zimmermann-Laband syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;20:457–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorlin RJ, Pinborg JJ, Cohen MM., Jr . 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 1976. Syndromes of the head and neck; pp. 329–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horning GM, Fisher JG, Barker BF, Kilroy WJ, Lowe JW. Gingival fibromatosis with hypertrichosis case report. J Periodontol. 1985;56:344–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.6.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Synder CH. Syndrome of gingival hyperplasia, hersutism and convulsions. J Pediatr. 1965;67:499–502. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(65)80413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wynne SE, Aldred MJ, Bartold MP. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis associated with hearing loss and supernumerary teeth : A new syndrome. J Periodontol. 1995;66:75–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oikarinen K, Salo T, Kaar ML, Lahtela P, Altonen M. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis associated with growth hormone deficiency. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28:335–9. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(90)90111-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher JP. Gingival abnormalities of genetic origin : P0 reliminary communication with special reference to hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Dent Res. 1966;45:597–612. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaju PP, Desai A, Desai RS, Jaju SP. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis : Case report and its management. Int J Dent. 2009;2009:153603. doi: 10.1155/2009/153603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi R. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis : A case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart IC, Pallos D, Bozzo L, Almeida OP, Marazita ML, O’Connell JR. Evidence of genetic heterogeneity for hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1758–64. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bittencourt LP, Campos V, Moliterno LF, Ribeiro DP, Sampaio RK. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis : R0 eview of the literature and a case report. Quintessence Int. 2000;31:415–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramer M, Stahl B, Burakoff R. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis : I dentification, treatment, control. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:493–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shekar I. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis. Saudi Dent J. 2002;14:143–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozzo L, Almeida OP, Scully C, Aldred MJ. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis : Report of an extensive four-generation pedigree. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:452–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipton DA, Howell KJ, Dabbous MK. Increased proliferation, collagen and fibronectin production by hereditary gingival fibromatosis fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 1997;68:524–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.6.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirasuna K, Okura M, Watatani K, Hayashido Y, Saka M, Matsuya T. Abnormal cellular property of fibroblasts from congenital gingival fibromatosis. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:381–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baptista IP. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis : A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:871–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller M, Truhe T. Lasers in dentistry : An overview. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;124:32–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pick RM. Using lasers in clinical dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:37–47. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozzo L, Machado MA, Almeida OP, Lopes MA, Coletta RD. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis : Report of three cases. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000;25:41–6. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.25.1.e254616x22403280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. 10th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders; 2006. Clinical Periodontology; pp. 379–380. [Google Scholar]

- 22.James PL, Prasad SV. Gingival fibromatosis : Report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:55–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunhan O, Gardner DG, Bostanci H, Gunhan M. Familial gingival fibromatosis with unusual histologic findings. J Periodontol. 1995;66:1008–11. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.11.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]