Abstract

Oral malignant melanomas are extremely rare lesions and occur commonly in the maxillary gingiva more frequently on the palate with fewer incidences in the mandibular gingiva. Though these lesions are biologically aggressive, they often go unnoticed since they are clinically asymptomatic in the early stages and usually present merely as a hyperpigmented patch on the gingival surface. These lesions if diagnosed at an early in situ stage are potentially curable and definitely have a better prognosis, but unfortunately as they are clinically asymptomatic, it results in delayed diagnosis thus making the prognosis extremely poor. This paper presents the case of a patient who visited our department with the complaint of darkened patches on the gums and his concern was purely aesthetic. There were no symptoms associated with the hyperpigmented lesions and hence the patient did not approach us earlier. When the lesions grew larger and were unsightly, the patient has seeked dental advice. Histopathologic investigation confirmed the diagnosis as ‘Oral Malignant Melanoma’. Though aggressive therapy was instilled immediately, unfortunately, the patient succumbed to death within a few months after diagnosis as the lesion was highly invasive. Due to the biologically aggressive but clinically silent nature of progression of the lesion, the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and early detection and diagnosis for any pigmented gingival lesions cannot be overemphasised. Diagnosis must be based on thorough detailed history and valid histologic evidence.

Keywords: Gingiva, hyperpigmentation, oral malignant melanoma, pigmented lesions

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is a malignant tumor comprising of melanocytes in which cells are derived from the neural crest that constitute the melanin pigment in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epithelium. Although most melanomas arise in the skin, they may also arise from mucosal surfaces.[1,2] Primary malignant melanoma has been described in virtually all sites and organ systems to where neural crest cells migrate.[3]

Although, malignant melanoma is the third most common skin malignancy, yet it comprises of only 3 to 5% of all cutaneous malignancies.[4] Malignant melanomas of the oral cavity are extremely rare accounting for 0.2-8% of all malignant melanomas.[5,6] The relative incidence of malignant melanoma among mucosal neoplasms of the head and neck is 0.07% as reviewed by Hormia and Vuori.[7] It is characterized by proliferation of malignant melanocytes along the junction between the epithelial and connective tissues as well as within the connective tissue. The most common site is the palate which accounts for about 40% of cases followed by the buccal gingiva which accounts for one third of the cases.[8] The maxillary gingiva is more commonly involved as compared to the mandibular gingiva.[9] Other oral sites include the buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth, tongue, and lips. When encountered, melanoma of the oral cavity is more frequently found in males than in females, while the reverse is true in cutaneous melanomas. Although oral malignant melanomas are rare, they tend to be more aggressive than their cutaneous counterparts and often prove to be fatal. The prognosis for patients with oral melanoma is much worse than for those with cutaneous lesions and the overall five-year survival rate is about 15-38%.[2,10]

In this paper, we present a rare and unusual case of a 42-year-old male patient who presented with hyperpigmented gingiva.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old male patient came to the Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology with the chief complaint of patches of darkened gums in comparison to the adjacent pink gums. The increased pigmentation was not associated with any symptoms and the patients concern was purely aesthetic. He noticed small isolated patches of hyperpigmentation on the buccal mucosa of the mandibular anterior region two years ago. There was a rapid spread of the hyperpigmented lesions to form larger patches involving a considerably large portion of the mandibular arch. The patient found these to be unsightly and aesthetically unpleasant and hence sought dental advice. He also noticed an isolated patch of the pigmentation appearing in the right mandibular posterior region. The lesion was not associated with pain or any kind of discomfort. The patient did not give any history of smoking or usage of smokeless tobacco or alcohol intake. There was no familial history of carcinomas.

On clinical examination, the hyperpigmented lesion was present only on the mandibular gingiva involving the marginal, interdental, and attached gingiva from the distal aspect of 32 to the distal aspect of 44 [Figure 1]. The lesion also involved the lingual aspect of the attached gingiva from the distal aspect of 32 to distal aspect of 44 [Figure 2]. There was also an isolated patch of pigmentation seen on the attached gingiva associated with a missing 46 [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Dispersed patches of hyperpigmented gingiva on the labial aspect of the mandibular anterior region

Figure 2.

Dispersed patches of hyperpigmented gingiva on the lingual aspect of the mandibular anterior region

Figure 3.

Isolated patch of pigmentation on the mandibular right gingiva

The lesion was blackish-blue in color with irregular raised borders clearly demarcated from the adjacent clinically normal gingiva and confined within the limits of the attached gingiva. The surface appeared wrinkled, proliferative, and granular. There was no evidence of bleeding from the surface [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Surface appearance: Wrinkled, proliferative and granular

On palpation, the lesion was fibrotic and non-tender. The regional lymphnodes were not palpable.

Based on the history and clinical examination, a differential diagnosis of Pigmented nevi, Melanoachanthoma, and oral malignant melanoma was derived upon. Reports of routine blood investigations were normal. Radiographs did not reveal any significant abnormal findings.

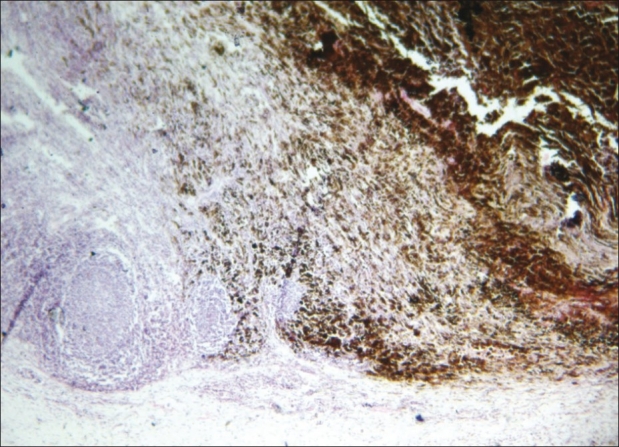

An incisional biopsy was performed and sent for histopathological investigation. The report revealed sheets of melanin containing pleomorphic cells in the connective tissue, confirming the diagnosis of ‘Oral Malignant Melanoma’ [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Histopathology: Sheets of melanin containing pleomorphic cells in the connective tissue

The patient was referred to an Oral and maxillofacial surgeon and an Oncosurgeon for further treatment. The required therapy was initiated immediately, but unfortunately due to the extremely aggressive and invasive nature of the tumor, the patient succumbed to death within four months of the therapy.

DISCUSSION

Oral malignant melanomas are extremely rare lesions, accounting for approximately 2% of all melanomas with only a few reported cases in literature.[11–13] Although mucosal melanoma was first described by Weber in 1895, the etiology of this disease is still obscure. Cigarette smoking, denture irritation, and alcohol consumption are some of the suggested risk factors, but their correlation is still unsubstantiated.[14] Tobacco and formaldehyde exposures have also been suggested as causative agents for intraoral melanomas.[15] In the present case, the patient was not exposed to any of these factors and hence the possible etiological factor for this patient is still unclear.

Onset of malignant melanomas is usually between the ages of 40 to 70 years (mean, 55 years).[16,17] The lesion is three times more common in men than in women. In the oral cavity, malignant melanoma almost exclusively occurs in the palate and maxillary gingiva with an incidence of 80% and 91.4%, respectively.[18,19] There are very few reported cases of malignant melanoma on the mandibular gingiva.[20–22] Our patient is one of those rare cases, as the site of occurrence of the lesion is the mandibular gingiva.

The patient had noticed appearance of the pigmented lesion about two years ago and it didn’t seem to proliferate at a rapid rate then. Most primary oral melanomas appear as new lesions from apparently normal mucosa, whereas about 30-50% are preceded by oral pigmentations for several months or even years. Some of the pre-melanoma lesions include mucosal melanosis and a variety of melanocytic nevi.[23,24] Oral melanosis has been suggested as a predisposing factor for the development of oral melanoma in 30 to 73% of patients.[25] However, although the incidence of melanosis in India is low, there in a higher occurrence of primary oral melanoma, thereby contraindicating this hypothesis.[26]

Primary oral melanoma is initially asymptomatic and progresses unnoticed by patients, contributing to delay in diagnosis. Generally, recognition of the lesion occurs when there is a breakdown of the overlying epithelium or hemorrhage.[27] It is a known fact that early diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanomas is imperative in order to reduce mortality. If the lesions are diagnosed in an initial stage where the cancer cells are limited to the epidermis layer of the skin, the melanoma is nearly 100% curable by excision.

Malignant melanomas can range from mucosal pink through brown and blue to black lesions with or without ulcerations. They could be flat or elevated with an erythematous border around it.

Oral melanoma may appear in various forms including pigmented macule, pigmented nodule, or a large pigmented exophytic lesion or an amelanotic variant of any of these three forms. Lopez et al. identified five types of oral malignant melanoma (OMM) on the basis of clinical appearance: Pigmented nodular type, non-pigmented nodular type, pigmented macular type, pigmented mixed-type, and non-pigmented mixed type.[28] This case could be identified as the pigmented nodular type of OMM.

The mucosal melanomas can show two principal patterns: An in situ pattern in which the neoplasm is limited to the epithelium and epithelial-connective tissue interface (junctional), and an invasive pattern in which the neoplasm is found within the supporting connective tissue.

Greene et al.[29] suggested the following criteria for a lesion to be considered as primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: 1) demonstration of malignant melanoma both histologically and clinically; 2) the presence of junctional activity; and 3) the inability to demonstrate any other primary site. Based on these criteria, this case could be considered as a primary oral malignant melanoma.

This tumor is characterized by marked aggressive and invasive behavior that manifests by both local and distant metastases to sites such as lungs, liver, brain, and bones.[30] Lymphatic metastasis at the time of diagnosis seems to be a crucial prognostic factor for oral melanomas.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJC) does not have published guidelines for the staging of oral malignant melanomas; yet, probably due to the rare occurrence of this lesion.

Surgery remains the preferred treatment along with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. It has been shown that recent surgical excision followed by immuno-chemotherapy has reduced or prevented the recurrence of the lesion, but there are only a few reported cases in literature.[31] Extensive research is still required on this front.

In the cases where metastasis has already occurred the disease is considered as classically incurable, surgery being considered only for palliative care[30] and other treatment modalities like radiotherapy and chemotherapy could be considered under the palliative care.

The prognosis of oral melanoma is poor with a five-year survival of 0–55% of cases. The median survival for all oral mucosal melanomas is slightly more than two years from the time of diagnosis.[32]

Primary mucosal melanomas are exceedingly rare and biologically aggressive malignancies. Tumors diagnosed early, essentially during the in situ stage, are potentially curable and have a better prognosis.

We, therefore, lay emphasis and reiterate on the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and early detection and diagnosis for any pigmented lesions, especially if they occur in high-risk sites like the palate or gingiva. Diagnosis must be based on thorough detailed history and valid histologic evidence.

CONCLUSION

Oral malignant melanoma though an extremely rare malignancy is potentially very aggressive and a rapidly invasive tumor. Clinically these tumors are very silent and asymptomatic in their appearance, tending to be misleading Thus, the importance of early detection and diagnosis which can be life saving cannot be overemphasised.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boulaadas M, Benazzou S, Mourtada F, Sefiani S, Nazih N, Essakalli L, et al. Primary oral malignant melanoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1059–61. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e3180f6120e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebenezer J. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:94–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey M, Abraham EK, Mathew A, Ahamed IM. Primary malignant melanoma of the upper aero-digestive tract. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boring CC, Squires TS, Tong T, Montgomery S. Cancer statistics 1994. CA Cancer J Clin. 1994;44:7–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.44.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pliskin ME, Mastrangelo MJ, Brown AM, Cister RP. Metastatic melanoma of the maxilla presenting as a gingival swelling. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41:101–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman S, Yohn J, Robinson W, Norris D. Melanoma: 1.Clinical characteristics. Hosp Prac. 1994;29:47–50. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1994.11443031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hormia M, Vuori EE. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. J Laryngol. 1969;83:349–59. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100070419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM. Oral mucosal melanoma: Epidemiology and pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:152–69. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983. A Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 133–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doval DC, Rao CR, Saitha KS, Vigayakumar M, Misra S, Mani K, et al. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: Report of 14 cases from a regional cancer centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22:245–9. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(96)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardekian L, Rosen DJ, Peled M, Rachmiel A, Machtei EE, el Naaj IA, et al. Primary gingival malignant melanoma. Report of 3 cases. J Periodontol. 2000;71:117–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson GR, DeFiebre BK, Firtell DN. Primary malignant melanoma of the mouth. J Oral Surg. 1979;37:349–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhry AP, Hamped A, Gorlin KJ. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity, a review of 105 cases. Cancer. 1958;11:923–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195809/10)11:5<923::aid-cncr2820110507>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman DM, Sigurdson A, Doody MM, Rao RS, Linet MS. Risk of melanoma in relation to smoking, alcohol intake, and other factors in a large occupational cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:847–57. doi: 10.1023/b:caco.0000003839.56954.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmstrom M, Lund VJ. Malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity after occupational exposure to formaldehyde. Br J Ind Med. 1991;48:9–11. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smyth AG, Ward-Booth RP, Avery BS, To EW. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity- an increasing clinical diagnosis? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;31:230–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90145-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapini RP, Golitz LE, Greer RO, Jr, Krekorian EA, Poulson T. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity.A review of 177 cases. Cancer. 1985;55:1543–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850401)55:7<1543::aid-cncr2820550722>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eneroth CM. Malignant Melanoma of the Oral Cavity. Int J Surg. 1975;4:191–7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(75)80025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka M, Mimura M, Ogi K, Amagasa T. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: Assessment of outcome from the clinical records of 35 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:761–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauzdar S, Rao DD, Arthanari KK, Krishnan G, Naikmasur VG, Revanappa MM. Malignant melanoma of the mandibular gingiva. Rare Tumors. 2010;2:e25. doi: 10.4081/rt.2010.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lourenço SV, Bologna SB, Colucci F, Neto CF, Montenegro FL, Nico MM. Oral mucosal melanoma of the mandibular gingiva: A case report. Cutis. 2010;86:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharon A, Ross AS. Primary malignant melanoma of the mandibular gingiva. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:545–8. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatch CL. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:185–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn MA, Weathers DR, Hoffman JG. Transformation of a benign oral pigmentation to primary oral melanoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takagi M, Ishikawa G, Mori W. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity in Japan.With special reference to mucosal melanosis. Cancer. 1974;34:358–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197408)34:2<358::aid-cncr2820340221>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soman CS, Sirsat MV. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity in Indians. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38:426–34. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowland HN, Schnetler JF. Primary malignant melanoma arising in the dorsum of the tongue. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:197–8. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Graniel CM, Ochoa-Carrilo FJ, Menese-Garcia A. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: Diagnosis and treatment experience in a Mexican population. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:425–30. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene GW, Haynes JW, Dozier M, Blumberg JM, Bernier JL. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:1435–43. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez EA, Alonso FC, Siles MS. Melanoma of the oral mucosa with cerebral metastasis: A clinical case. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umeda M, Komatsubara H, Shigeta T, Ojima Y, Minamikawa T, Shibuya Y, et al. Treatment and prognosis of malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: Preoperative surgical procedure increases risk of distant metastasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chidzonga MM, Mahomva L, Marimo C, Makunike-Mutasa R. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1117–20. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]