Abstract

Surfactants are found in many existing therapeutic, cosmetic, and agro-chemical preparations. In recent years, surfactants have been employed to enhance the permeation rates of several drugs via transdermal route. The application of transdermal route to a wider range of drugs is limited due to significant barrier to penetration across the skin which is associated with the outermost stratum corneum layer. Surfactants have effects on the permeability characteristics of several biological membranes including skin. They have the potential to solubilize lipids within the stratum corneum. The penetration of the surfactant molecule into the lipid lamellae of the stratum corneum is strongly dependent on the partitioning behavior and solubility of surfactant. Surfactants ranging from hydrophobic agents such as oleic acid to hydrophilic sodium lauryl sulfate have been tested as permeation enhancer to improve drug delivery. This article reviews the status of surfactants as permeation enhancer in transdermal drug delivery of various drugs.

KEY WORDS: Penetration enhancer, surfactant, skin, sodium lauryl sulfate, Tween 80

Nowadays, the transdermal route has become one of the most successful and innovative focus for research in drug delivery, with around 40% of the drug candidate being under clinical evaluation related to transdermal or dermal systems. But the barrier property of skin causes difficulties for transdermal delivery of therapeutic agents.[1] One long-standing approach to increase the range of drugs that can be effectively delivered via this route has been to use penetration enhancers, chemicals that interact with skin constituents to promote drug flux.[2] Skin penetration enhancers are molecules which reversibly remove the barrier resistance of the stratum corneum. They allow drugs to penetrate more readily to the viable tissues and thus enter the systemic circulation.[3] Usually, surfactants are added to formulations in order to solubilize lipophilic active ingredients, so they have potential to solubilize lipids within the stratum corneum.[2] Surfactants induce a concentration-dependent biphasic action with respect to alteration of skin permeability. At low concentrations, surfactants increase the permeability of the skin to many substances probably because they penetrate the skin and disrupt the skin barrier function.[4]

Surfactants are amphipathic molecules that consist of a non-polar hydrophobic portion usually a straight or branched hydrocarbon or fluorocarbon chain containing 8-18 carbon atoms, which is attached to a hydrophilic portion. The hydrophilic portion can be nonionic, ionic or zwitterion.[5] Surfactants are low to moderate molecular weight compounds which contain one hydrophobic part, which is readily soluble in oil but sparingly soluble or insoluble in water, and one hydrophilic (or polar) part, which is sparingly soluble or insoluble in oil but readily soluble in water.

Classification of Surfactants

Surfactants are classified according to the nature of their polar head groups[6] i.e.

Anionic Surfactants

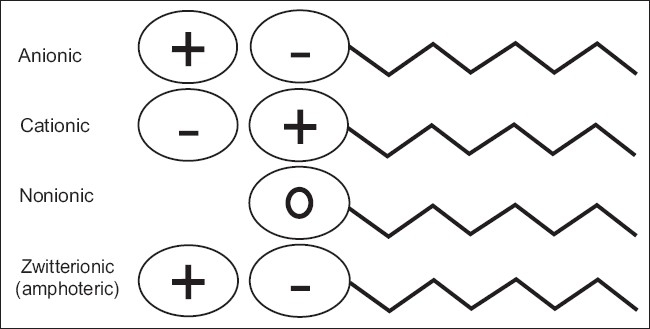

Surfactants in which the hydrophilic part carries a negative charge [Figure 1]. Examples of anionic surfactants include the following:

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the various types of surfactants

Carboxylates: Alkyl carboxylates-fatty acid salts (“soaps”); carboxylate fluoro surfactants.

Sulfates: Alkyl sulfates (RCOO) (e.g.,sodium lauryl sulfate); alkyl ether sulfates (e.g.,sodium laureth sulfate).

Sulfonates: Docusates (e.g.,dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate); alkyl benzene sulfonates.

Phosphate esters: Alkyl aryl ether phosphates; alkyl ether phosphates

Nonionic Surfactants

Surfactants that do not ionize in aqueous solution, because their hydrophilic group is of a non-dissociable type, such as alcohol, phenol, ether, ester, or amide [Figure 1]. A large proportion of these nonionic surfactants are made hydrophilic by the presence of a polyethylene glycol chain, obtained by the polycondensation of ethylene oxide. Non ionic surfactants, i.e., surfactants with an uncharged polar head group, are probably the ones used most frequently in drug delivery applications. The critical micellization concentration for such surfactants is generally much lower than that of the corresponding charged surfactants, and partly due to this, such surfactants are generally less irritant and better tolerated than the anionic and cationic surfactants, e.g., polyoxyethylenes, poloxamer (188,407,338,184), poloxamine (304,904,908), polysorbates.

Cationic Surfactants

Cationic surfactants are dissociated in water into an amphiphilic cation and an anion, most often of the halogen type [Figure 1]. A very large proportion of this class corresponds to nitrogen compounds such as fatty amine salts and quaternary ammoniums, with one or several long chain of the alkyl type, often coming from natural fatty acids.

Zwitterionic Surfactants

Zwitterionic surfactants are less common than anionic, cationic and non ionic ones. When a single surfactant molecule exhibits both anionic and cationic dissociations it is called amphoteric or zwitterionic. The polar head group consists of a quaternary amine group and a sulfonic or carboxyl group [Figure 1]. This is the case of synthetic products like betaines or sulfobetaines and natural substances such as aminoacids and phospholipids (phosphatidylcholine, sphosphatidylethanolamine).

Surfactant-Skin Interaction

Many of the properties of surfactants can be related to their ability to concentrate at phase interfaces, leading to a reduction in interfacial tension. In biological systems the effect of surfactants are complex; particularly their effect on cell and other membranes, and this can lead to alterations in permeability characteristics.[7] The ability of surfactants to adsorb at interfaces and bind through hydrophobic or polar interactions may lead to desirable or undesirable effects on the skin depending on the surfactant concentration, the type of exposure, the duration of contact, and the individual response. The undesirable effects of surfactants on skin have been and are still extensively studied in vivo, by using human volunteers, and with in vitro screening tests, to predict the clinical effects of an individual surfactant as well as formulations.[8] The selection of a surfactant as a penetration enhancer should be based not only on its efficacy in enhancing skin permeation but also on its dermal toxicity (low) and its physicochemical and biological compatibility with the system's other components.[9]

Interaction of surfactants upon contact with skin:

By binding to the surface proteins of the skin

By denaturing skin surface proteins

By solubilizing or disorganizing the intercellular lipids of the skin

By penetrating through the epidermal lipid barrier

By interacting with living cell.[10]

Interaction with skin proteins

For the surfactant molecules to interact with the deeper protein - rich regions in a normal corneum, they must diffuse through the lipid region.[11] After binding to the proteins, surfactant causes the protein to denature, leading to the swelling of stratum corneum.[10] Solubilization of fluid lipids and abstraction of calcium or other multivalent ions to reduce corneocyte adhesion enhances the accessibility of the proteins in the lower regions of the stratum corneum.[11] Rhein et.al. investigated swelling of isolated stratum corneum when exposed to various single surfactant solutions and showed that the swelling was concentration and time dependent up to the CMC before leveling off.[12] Ionic interactions between the anionic head groups and the cationic sites of the proteins are a basic requirement to induce strong hydrophobic interactions between surfactant molecule and the protein; interactions will ultimately lead to protein denaturation.[8] Anionic surfactants have ability to solubilize the less soluble proteins such as zein, or can themselves remain on the skin due to formation of chemical compounds with skin keratin. Anionic promote the dissolution of the proteins out of the skin, cause release of sulfhydryl groups from the sclera proteins, react upon various enzymes of skin and finally denaturize. Nonionic surfactant binds to proteins via weak hydrophobic interaction.[13]

Interaction with the intercellular skin lipids

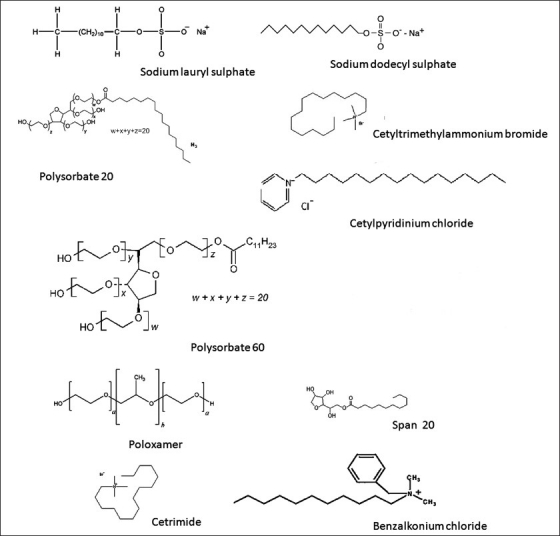

The protective lipid barrier of skin is composed of highly organized lipid layers located between the cells of stratum corneum. Surfactants have to integrate into lipid bilayers to disorganize them and alter skin barrier function. Monomers of surfactant can easily reach the intercellular lipids making the effect dependent on the relative proportion of monomer in solution.[8] Fulmer et.al. studied significant changes in stratum corneum lipid composition caused by sodium dodecyl sulfate [Figure 2]. The free cholesterol to cholesterol ratio was found to be increased while the quantity of total sterols remained constant. The distribution of certain ceramide species was also found to be altered.[14] Low concentrations of surfactant may emulsify stratum corneum lipids and improve permeability; however higher concentrations promote the formation of micelles in the vehicle that trap the permeant and decrease permeability.[15] It was found that SLS [Figure 2] enhances penetration into the skin by increasing the fluidity of epidermal lipids. The increase in lipid fluidity below the applied site may allow sodium lauryl sulfate to diffuse in all directions including the radial path.[16]

Figure 2.

Structures of some of the commonly used surfactants

Interaction with living cells

Once the lipid barrier of skin has been disrupted/ weakened, monomers of surfactant can reach the living part of the epidermis and interact with keratinocytes and langerhans cells.[8] It was found that short-term treatment of skin with sodium lauryl sulfate (0.5% v/v) disorganized the stratum corneum, induced maturation of langerhans cells, and did not result in epidermis thickening.[17]

Factors governing the activity of surfactant as a penetration enhancer

The effect of surfactant in altering the skin barrier depends on the surfactant structure; both the hydrophobic alkyl chain and the hydrophilic ethylene oxide chain demonstrate some structure-activity behavior.[18] In a study Walters et al. reported that surfactants having a linear alkyl chain greater than C8 and an ethylene oxide chain length of less than E14 caused significant increase in the flux of methyl nicotinate while those having branched or aromatic moieties in the hydrophobic portion were ineffective.[19] In another study it was found that dimethyldialkylammoniums (double chained) with relatively shorter alkyl chains, which form either vesicles with looser molecular packing or micelles and appear to be present as surfactant monomer in higher ratios than those with longer alkyl chains, favor the interaction with skin.[20] In many biological systems, including skin, surfactants with a similar hydrophilic group will show maximum membrane activity if they possess a decyl or dodecyl alkyl chain. Park et.al. reported that the enhancers containing the ethylene oxide chain length of 2-5, HLB value of 7-9 and an alkyl chain length of C16 -C18 were effective promoters of ibuprofen flux.[21] In a study the parabolic relation between the piroxicam absorption and the polyoxyethylene length of non ionic surfactant was observed.Polyoxyethylene length from 5 to 15 was found to enhance percutaneous absorption to a greater extent.[22] Dalvi and Zatz examined the influence of polyoxyethylene chain (POE) length of polyoxyethylenenonphenyl ether on penetration of benzocaine through hairless mouse skin from the aqueous solution system and found that the maximum flux was obtained by POE(9) followed by POE(12), POE(30), POE(50).[12]

Sorbitan monooleate (HLB 4.3) and polyoxyethylene n-lauryl ether (HLB 12.8) were found to interact with the human epidermis in degrees which were dependent on the polarity of the surfactant.[23] Kushla et.al. studied penetration of lidocaine through human epidermis by incorporating cationic surfactants of varying alkyl chain length from three classes:alkyl dimethylbenzyl ammonium halides, alkyl trimethyl ammonium halides, and alkyl pyridinium halides. Peak surfactant enhancement effects were seen at alkyl chain lengths of 12 or 14 carbons.[24] The nature of the enhancer head group also greatly influences cutaneous barrier impairment. Tween 20 (log Poct=3.72) which is more hydrophilic than Span20 (log Poct = 4.26) was found to be less effective in enhancing 5-fluorouracil skin penetration. Lipophilic molecules diffuse through the stratum corneum by solubilizing in the continuous intercellular lipid phase of the stratum corneum (lipophilic pathway). Span20 was found to affect the intercellular lipids by making them more fluid and enhancing the diffusivity.[25] SLS was found to remove detectable levels of lipids only above its critical micelle concentration (CMC). At high concentrations the surfactants removed only very small amounts of cholesterol, free fatty acid, the esters of those materials, and possibly squalene. Below the CMC, sodium lauryl sulfate bound and irritates the stratum corneum.[26]

Mechanism of Action

Ionic surfactant

Ionic surfactant molecules in particular tend to interact well with keratin in the corneocytes, open up the dense keratin structure and make it more permeable.[27] They are also thought to enhance transdermal absorption by disordering the lipid layer of stratum corneum.[28]

Anionic surfactants

Anionic surfactants interact strongly with both keratin and lipids.[29] It has been reported that anionic surfactants like sodium lauryl sulfate can penetrate and interact with the skin, producing large alterations in the barrier properties.[30] An additional mechanism for the penetration enhancement by SLS involves the hydrophobic interaction of the SLS alkyl chain with the skin structure which leaves the end sulfate group of the surfactant exposed, creating additional sites in the membrane. This results in the development of repulsive forces that separate the protein matrix, uncoil the filaments, and expose more water binding sites, hence increasing the hydration level of skin.[12]

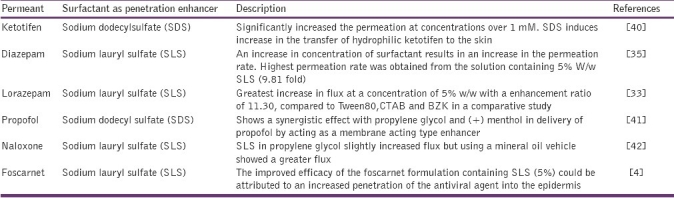

Anionic materials tend to permeate relatively poorly through stratum corneum upon short-time exposure but permeation increases with application time.[2] The alkyl sulfates can penetrate and destroy the integrity of the stratum corneum within hours of application.[18] Anionic surfactants cause greater enhancement and damage than non ionic surfactants. Anionic has been found to increase deuterated water permeability of human epidermis in vitro. The surfactants such as sodium lauryl sulfate, after extended treatment, irreversibly caused protein denaturation, membrane expansion, hole formation, and the loss of water -binding capacity.[31] Table 1 depicts the use of various anionic surfactants as enhancers in transdermal drug delivery.

Table 1.

Application of anionic surfactants as penetration enhancer in transdermal drug delivery

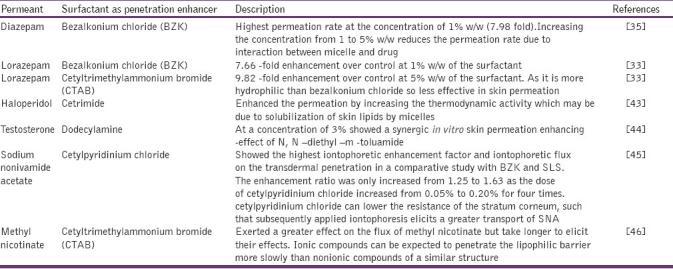

Cationic surfactants

Molecules show main action on keratin fibrils of the cornified cells and result in a disrupted cell/ lipid matrix. Cationic surfactants interact with skin proteins via polar interactions and hydrophobic binding. Hydrophobic interaction between surfactant chains and the protein result in pendant ionic head groups and subsequently swelling of the stratum corneum.[23] Cationic molecules are more destructive to skin tissues causing a greater increase in flux than anionic surfactants.[32] Table 2 illustrates the role of cationic surfactants as penetration enhancers.

Table 2.

Application of cationic surfactants as penetration enhancer in transdermal drug delivery

Non-ionic surfactants

Nonionic surfactants, which are a safe class of enhancers, also offer a means of enhancing drug permeation through the skin. Nokhodchi et.al.[33] reported two -possible mechanisms by which the rate of transport is enhanced using nonionic surfactants.

Firstly the surfactant may penetrate into the intercellular regions of stratum corneum, increase fluidity and eventually solubilize and extract lipid components.

Secondly penetration of surfactant into the intercellular matrix followed by interaction and binding with keratin filaments may result in a disruption within the corneocyte.[33]

In addition non ionic surfactants are able to emulsify sebum, thereby enhancing the thermodynamic coefficient of drugs and allowing it to penetrate into the cells more effectively.[7]

Polysorbates which are a prominently safe class of surfactants offer a means of enhancing drug permeation through the skin. Polysorbate surfactants [Figure 2] demonstrated a significant increase of drug permeation up to 13 -fold when applied to hairless mouse skin.[34] Polysorbate 80 contains the ethylene oxide and a long hydrocarbon chain and this feature imparts both lipophilic and hydrophilic characteristics to this enhancer, allowing it to partition between lipophilic mortar substance and the hydrophilic domain.[35] Sorbitan monopalmitate, sorbitan trioleate, polyoxyl 8 stearate, polyoxyethylene 20 cetyl ether, or polyoxyethylene 2 oleyl ether 10% (w/w) significantly enhanced the percutaneous absorption of flufenamic acid and sodium salicylate when incorporated into white petrolatum USP ointment base.[36,37]

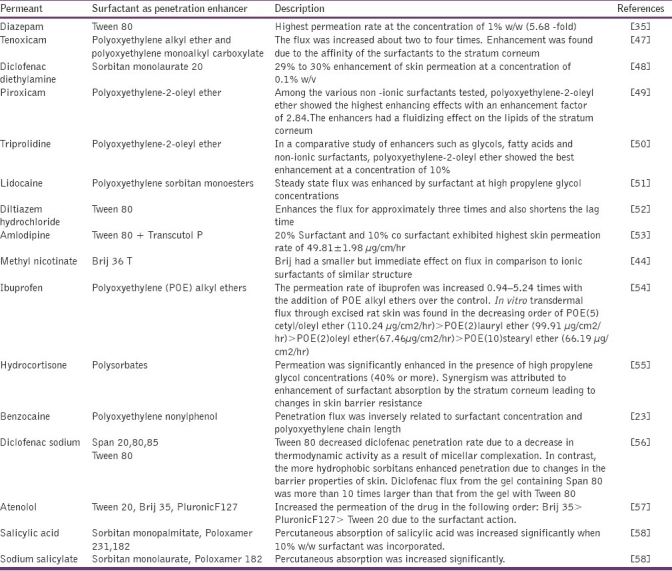

The effect of nonionic surfactant on the rate of the permeation of drug compound through membranes from a formulation is highly dependent on the physical state of surfactant and its concentration in the locality of the membrane.[38] Table 3 presents the mostly used nonionic surfactants in TDDS as penetration enhancers.

Table 3.

Application of nonionic surfactants as penetration enhancer in transdermal drug delivery

Zwitterionic surfactants

Ridout et.al. studied the action of five zwitterionic surfactants on the barrier function of hairless mouse skin and suggested that solubilization of stratum corneum lipids may be an important mechanism of penetration enhancement. The surfactants considered for study were dodecylbetaine, hexadecylbetaine, hexadecylsulfobetaine, N, N–dimethyl–N-dodecyl amine oxide, dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide.[39]

Regulatory Aspects of Surfactants

Safety has always been the most important requirement and the most studied when dealing with pharmaceutical drugs. In the United States, the food and drug administration (FDA) has published listings in the code of federal regulations (CFR) for GRAS substances that are generally recognized as safe.[59]

In general, nonclinical and clinical studies are required to demonstrate the safety of a new surfactant before use. The US FDA has published a guidance document for industry on the conduct of nonclinical studies for the safety evaluation of new pharmaceutical excipients.[60] This guidance not only provides the types of toxicity data to be used in determining whether a potential new excipient is safe, but also describes the safety evaluations for excipients proposed. The document also depicts testing strategies for pharmaceuticals proposed for short -term, intermediate, and long -term use.[60] More importantly, this guidance highlights the importance of performing risk -benefit assessments on proposed new excipients in the drug products while establishing permissible and safe limits for the excipients.It is often possible to assess the toxicology of an excipient in a relatively efficient manner. Existing human data for some excipients can substitute for certain nonclinical safety data. In addition, an excipient with documented prior human exposure under circumstances relevant to the proposed use may not require evaluation with a full battery of toxicology studies.[60]

Conclusion

The effect of surfactants on the enhancement of drug permeation through skin has been well reviewed. Research in this area has proved the usefulness of surfactants as chemical penetration enhancer in the transdermal drug delivery. In many instances they have been found to be more effective than other enhancers. Focus should be on skin irritation and toxicity with a view to select from a wide range of surfactants.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kumar R, Philip A. Modified Transdermal Technologies: Breaking the barriers of drug permeation via the skin. Tropical J Pharm Res. 2007;6:633–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams AC, Barry BW. Penetration enhancers. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2004;56:603–18. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry BW. Mode of action of penetration enhancers in human skin. J Control Release. 1987;6:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piret J, Désormeaux A, Cormier H, Lamontagne J, Gourde P, Juhász J, et al. Sodium lauryl sulfate increases the efficacy of a topical formulation of foscarnet against herpes simplex virus type 1 cutaneous lesions in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2263–70. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2263-2270.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tadros TF. Applied surfactants: Principles and applications. KGaA:Weinheim: Wiley-VcH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2005. p. 437. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malmsten M. Surfactants and Polymers in drug delivery. Sweden: Marcel dekker; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith EW, Maibach HI. Percutaneous penetration enhancer. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somasundaran P, Hubbard A. Encyclopedia of Surface and Colloid Science. Pezron I. 2nd ed. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen LV, Popovich NG, Ansel HC. Pharmaceutical dosage forms and drug delivery systems. 8th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barel AO, Paye M, Maibach HI. Handbook of cosmetic science and technology. 3rd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananthapadmanabhan KP, Yu KK, Meyers CL, Aronson MP. Binding of surfactants to Stratum Corneum. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1996;47:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhein LD, Robbins CR, Fernee K, Cantore R. Surfactant structure effects on swelling of isolated human stratum corneum. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1986;37:125–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gloxhuber C, Kunstler K. Surfactant science series. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. Anionic surfactants: Biochemistry, toxicology, dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulmer AW, Kramer GJ. Stratum corneum lipid abnormalities in surfactant induced dry scaly skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86:598–02. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jantharaprapap R, Stagni G. Effects of penetration enhancers on in vitro permeability of meloxicam gels. Int J Pharm. 2007;343:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patil S, Singh P, Maibach H. Radial spread of sodium lauryl sulfate after topical application. Pharm Res. 1995;12:2018–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1016220712717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang CM, Wang CC, Kawai M, Barnes S, Elmets CA. Surfactant sodium lauryl sulfate enhance skin vaccination. [Accessed November 28, 2005]. Available from: http://www.mcponline.org/content/5/3/523.full . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Walters KA, Bialik W, Brain KR. The effects of surfactants on penetration across the skin. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1993;15:260–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.1993.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters KA, Walker M, Olejnik O. Non-ionic surfactant effects on hairless mouse skin permeability characteristics. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:525–29. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitagawa S, Kasamaki M, Hiyama F. Effects of double-chained cationic surfactants n-dimethyldialkylammoniums on skin permeation of benzoic acid through excised guinea pig dorsal skin: comparison of their enhancement effects with hemolytic effects on erythrocytes. Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:1155–58. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park ES, Chang SY, Hahn M, Chi SC. Enhancing effect of polyoxyethylene alkyl ethers on the skin permeation of ibuprofen. Int J Pharm. 2000;209:109–19. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuyama H, Ikeda Y, Kasai S, Imamori K, Takayama K, Nagai T. Influence of non-ionic surfactants, pH and propylene glycol on percutaneous absorption of piroxicam from cataplasm. Int J Pharm. 1999;186:141–48. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalvi UG, Zatz J. Effects of nonionic surfactants on penetration of dissolved benzocaine through hairless mouse skin. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1999;32:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kushla GP, Zatz JL. Correlation of water and lidocaine flux enhancement by cationic surfactants in vitro. J Pharm Sci. 1991;80:1079–83. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600801117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez A, Llinares F, Cortell C, Herraez M. Comparative enhancer effects of Span® 20 with Tween® 20 and Azone® on the in vitro percutaneous penetration of compounds with different lipophilicities. Int J Pharm. 2000;202:133–40. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froebe CL, Simion FA, Rhein LD, Cagan RH, Kligman A. Stratum corneum lipid removal by surfactants: Relation to in vivo irritation. Dermatologica. 1990;181:277–83. doi: 10.1159/000247822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aulton ME. Pharmaceutics -The science of dosage form design. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (US): Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swarbrick J. Encyclopedia of pharmaceutical technology.Surfactants in pharmaceutical products and systems. 3rd ed. Vol. 6. Informa Healthcare, CRC press hardcover; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiger MM, Rhein LD. Surfactant in Cosmetics. Vol. 68. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CK, Uchida T, Kitagawa k, Yagi K, Kim NS, Goto S. Skin permeability of various drugs with different lipophilicity. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:562–65. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600830424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheuplein RJ, Ross L. Effects of surfactants and solvents on the permeability of epidermis. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1970;21:853–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker RB, Smith EW. The role of percutaneous penetration enhancer. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1996;18:295–01. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nokhodchi A, Shokri J, Dashbolaghi A, Hassan-zadeh D, Ghafourian T, Barzegar-jalali M. The enhancement effect of surfactants on the penetration of lorazepam through rat skin. Int J Pharm. 2003;250:359–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappel MJ, Kreut J. Effect of nonionic surfactants on transdermal drug delivery: I. Polysorbates. Int J Pharm. 1991;69:143–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shokri J, Nokhodchi A, Hassan-zadeh D, Ghafourian T, Barzegar-jalali M. The effect of surfactants on the skin penetration of diazepam. Int J Pharm. 2001;228:099–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen WW, Danti AG, Bruscato FN. Effect of nonionic surfactants on percutaneous absorption of salicylic acid and sodium salicylate in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. J Pharm Sci. 1976;65:1780–83. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600651222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang CC. Percutaneous absorption of flufenamic acid in rabbits: effect of dimethyl sulfoxide and various nonionic surface-active agents. J Pharm Sci. 1983;72:857–60. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600720805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walters KA, Hadgraft J. Pharmaceutical skin penetration enhancement. Vol. 59. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridout G, Hostynek JJ, Reddy AK, Wiersema RJ, Hodson CD, Lorence CR, et al. The effects of zwitterionic surfactants on skin barrier function. Fundamental and applied toxicology. 1991;16:41–50. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(91)90133-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitagawa S. Enhanced skin permeation of cationic drug ketotifen through excised guinea pig dorsal skin by surfactants with different electric charges. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:1183–85. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keisuke Y, Yuri T, Hidero A, Kazuyuki T, Hiraku O, Yoshiharu M. Effect of penetration enhancer on transdermal delivery of propofol. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:677–83. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aungst BJ, Rogers NJ, Shefter E. Enhancement of naloxone penetration through human skin in vitro using fatty acids, fatty alcohols, surfactants, sulphoxides and amides. Int J Pharm. 1986;33:225–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaddi HK, Wang LZ, Ho PC, Chan SY. Effect of some enhancer on the permeation of haloperidol through rat skin in vitro. Int J Pharm. 2001;212:247–55. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao H, Choi MK, Kim JS, Yong CS, Choi HG, Chung SJ, et al. Synergistic enhancing effect of DEET and dodecylamine on the skin permeation of testosterone from a matrix type transdermal delivery system. Drug Deliv. 2009;16:249–53. doi: 10.1080/10717540902896586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang JY, Fang CL, Huang YB, Tsai YH. Transdermal iontophoresis of sodium nonivamide acetate.III combined effect of pretreatment by penetration enhancer. Int J Pharm. 1997;149:183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashton P, Walters KA, Brain KR, Hadgraft J. Surfactant effects in percutaneous absorption effects on the transdermal flux of methyl nicotinate. Int J Pharm. 1992;87:261–64. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Endo M, Yamamoto T, ljuin T. Effect of nonionic surfactants on the percutaneous absorption Tenoxicam. Chem Pharm Bull. 1996;44:865–67. doi: 10.1248/cpb.44.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukherjee B, Priya K, Mahapatra S, Das S. Sorbitan monolaurate 20 as a potential skin permeation enhancer in transdermal patches. J App Res. 2005;5:96–98. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shin SC, Cho CW, Oh I.J. Effects of non-ionic surfactants as permeation enhancers towards piroxicam from the poloxamer gel through rat skins. Int J Pharm. 2001;222:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin SC, Lee HJ. Enhanced transdermal delivery of triprolidine from the ethylene-vinyl acetate matrix. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;54:325–28. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarpotdar PP, Zatz JL. Evaluation of penetration enhancement of lidocaine by nonionic surfactants through hairless mouse skin in vitro. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75:176–81. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600750216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Limpongsa E, Umprayn K. Preparation and evaluation of diltiazem hydrochloride diffusion controlled transdermal drug delivery. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2008;9:464–70. doi: 10.1208/s12249-008-9062-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar D, Aqil M, Rizwan M, Sultana Y, Ali M. Investigation of a nanoemulsion as vehicle for transdermal delivery of Amlodipine. Pharmazie. 2009;64:80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park ES, Chang SY, Hahn M, Chi SC. Enhancing effect of polyoxyethylene alkyl ethers on the skin permeation of ibuprofen. Int J Pharm. 2000;209:109–19. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarpotdar PP, Zatz JL. Percutaneous Absorption Enhancement by Nonionic Surfactants. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1987;13:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arellano A, Santoyo S, Martn C, Ygartua P. Surfactant effects on the in vitro percutaneous absorption of diclofenac sodium. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1998;23:307–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03189356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhaskaran S, Harsha SN. Effect of permeation enhancer and iontophoresis on permeation of atenolol from transdermal gels. Ind J Pharm Sci. 2000;62:424–26. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen WW, Danti AG, Bruscato FN. Effect of nonionic surfactants on percutaneous absorption of salicylic acid and sodium salicylate in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. J Pharm Sci. 1976;5:1780–83. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600651222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 182, 184, 186. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 60.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Guidance for Industry: Nonclinical studies for the safety evaluation of pharmaceutical excipients,Office of Training and Communication, Division of Drug Information, HFD-240, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, or Office of Communication, Training, and Manufacturers Assistance, HFM-40,Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research,Food and Drug Administration. 2005 May; http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/5544fnl.pdf . [Google Scholar]